1 Introduction

The pulp and paper industry is faced to a global environmental challenge, which implies the reduction of the energy consumption needed during the processes and the reduction of the total rejects in the environment.

Thus, as much as 45 to 65% of the total energy needed in a mill is consumed during the pulping and refining steps [1]. This may explain the active research currently underway on the basics of energy savings mechanisms and on process development, ranging from machinery to biotechnology [1,2].

We recently demonstrated that the solubilisation of MnO2 by oxalate at pH 2.5 could form Mn-chelates able to oxidize lignin within the cell wall of wheat straw, poplar and spruce sawdust [3–5]. The biochemical analysis performed on plant cell wall revealed two separate effects of the oxalate and of the Mn-oxalate chelates: the first was mainly targeted toward polysaccharides, whereas the second was mainly targeted toward lignins, mimicking to some extend the ligninolytic Mn peroxidase enzyme [6,7].

Thus, we decided to test if such biochemical and abiotic Mn chelates could modify the cell wall structure and enhance the fibre separation efficiency during a thermomechanical (TMP) high-yield pulping process [8].

For this purpose, wood chips were treated by either MnO2/oxalate or oxalate alone. The energy needed to produce the pulps was determined, as well as their technical properties [9]. The impacts on the cell-wall ultrastructure and on the polymer structure were further investigated, in order to understand the underlying mechanisms [10].

This paper aims at describing a first picture of the impact of oxalate salts at acidic pH on the conversion process of poplar wood chips into fibres.

2 Experimental

2.1 Plant material and substrates

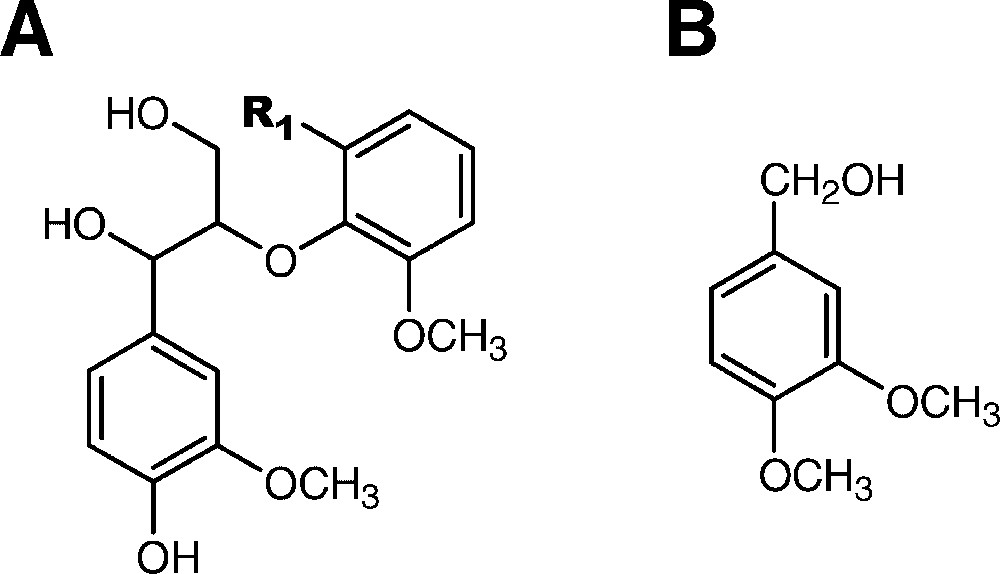

Poplar wood was used as extractive free sawdust (Populus trichocarpa, cv Fritzi Pauley) or industrial chips, from the STORA-ENSO plant (Corbéhem, France) [3,10]. Lignin model compounds, of the G-G (Guaiacyl) and G-S (Guaiacyl-Syringyl) types, were synthesized according to the previously published methods [11] (Fig. 1). Other substrates (veratryl alcohol, birch xylans) were commercial products of analytical grade (Sigma Aldrich; Fluka).

Structures of models described in the text: (A) dimers representing the main β-O-4 linkage present in lignins; G=guaiacyl; S= syringyl; G-G type:

2.2 Chemicals

Sodium–oxalate and oxalic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (France). Other reagents and solvents used were of analytical grade.

2.3 Treatment of wood by oxalate

The poplar wood chips (500 g) were incubated during 6 h at 25 °C in 5 l of a 200-mM Na-oxalate buffer (pH 2.5); the poplar sawdust (50 mg) was incubated during 20 h at 25 °C in 10 ml of a 100-mM Na-oxalate buffer (pH 2.5). The control experiments consisted in the incubation of the samples in water, during 6 or 20 h, at 25 °C.

At the end of the reaction period, the samples were recovered by vacuum filtration and washed with hot water (tap water for chips, deionised for sawdust) to remove oxalate salts. The samples were then freeze-dried before chemical analysis. For microscopic analysis, the samples were prepared as previously described [4,12].

2.4 Treatment of model compounds by oxalate

The lignin model compounds of the G-G and G-S type (30 mg) were incubated in 5 ml of a 200-mM Na-oxalate buffer (pH 2.5) during 6 h at 25 °C (Fig. 1A). Veratryl alcohol (

2.5 Chemical analysis

2.5.1 Lignin content and characterization

The lignin content in the sample was determined according to a procedure similar to that described by Effland [13] or by the TAPPI standard method (#T-222; http://www.tappi.org). The lignin fraction is accounted for as the acid insoluble fraction depleted from its ashes.

The content of monomer structures released by the thioacidolysis method was determined according to the published procedures [14]. The yields of the guaiacyl (G) and syringyl (S) monomers reflect the amount of such units only involved in α or β-O-4 bonds.

2.5.2 Polysaccharide composition

Polysaccharides in samples were hydrolysed by H2SO4 according to [15]. The monosaccharides released by the treatments were analysed by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography (HP-AEC) with pulsed amperometry detection, as described previously [16]. Pentosan content in pulps was determined according to the standard NFT 12-008 method (http://www.boutique.afnor.fr/).

2.5.3 Characterization of reaction products issued from lignin model compounds and veratryl alcohol

Reaction products issued from parent lignin model compounds were extracted by ethyl acetate or dichloromethane, or directly recovered as a hydrophobic resin coming out from the water phase of the reaction medium. The products were analysed by size-exclusion chromatography (HP-SEC) and/or reverse phase liquid chromatography (HPLC, C18 phase, CH3CN/H2O eluents), as previously described [10,16]. Preparative HPLC was used to fractionate and purify selected dimeric constituents, which were after characterized by 1H and 13C NMR, GC-MS and elemental composition (unpublished; communicated at the 8th ICBPPI, Helsinki, Finland, 2001; see also [17]).

2.5.4 Viscosimetric measurement of xylan solutions

Viscosimetry of xylans solutions was determined by capillary flow-rate measurement according to the ISO 5351:2004 protocol (http://www.iso.ch/iso/fr). The calibration of the system was performed by determining the viscosities (i) of the oxalate buffer alone and (ii) of a reference solution of xylan in water.

2.6 Microscopy

Low-field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at medium magnification level was used to analyse the surface aspects of the freeze-dried samples. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on ultrathin sections of dehydrated samples embedded in LR-White resin (London Resin Company). The tissues were stained for polysaccharides with the periodic acid-silver reagent (PATAg) of Thiery adapted by Ruel [18].

2.7 Thermomechanical pulping of poplar

Industrial poplar chips from the STORA-ENSO plant were used. The chips underwent first a mechanical pre-treatment in a Modular Screw Device (MSD)

2.8 Pulp quality evaluation

Fibre morphological characteristics were determined by analysis with PQM 1000 (Metso, Finland). The physical and optical properties of pulps were evaluated on paper handsheets according to ISO standards (http://www.iso.ch/iso/fr).

3 Results and discussion

This paper aims at combining information obtained at different scale levels of the cell wall on the impacts of oxalate buffer on the conversion of wood material into fibres.

3.1 Modification of cell wall ultrastructure by oxalate

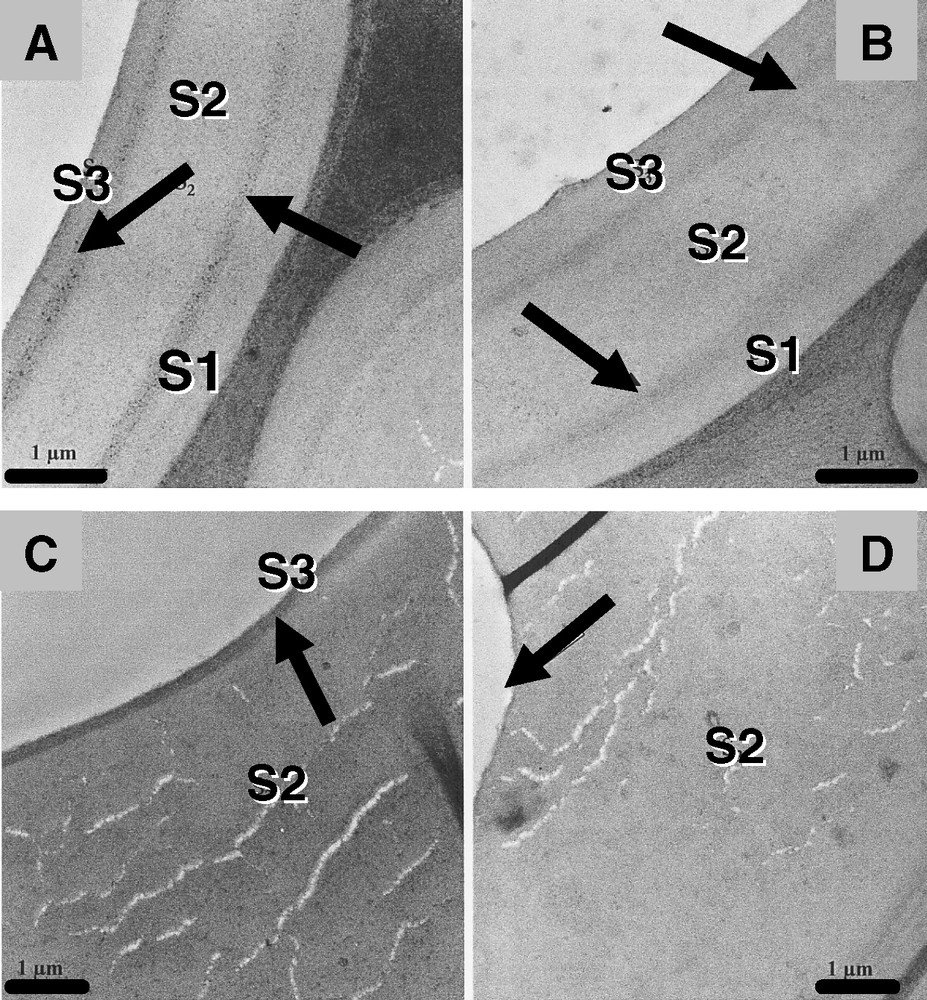

An intermediate level of observation of the cell wall complexity is its ultrastructure. In TEM, PATAg staining for polysaccharides in poplar wood chips showed that the contrasted areas delimiting the different layers S1, S2 and S3 in normal wood appeared less marked in oxalate treated samples (Fig. 2A and B); the limit between S2 and S3 also sometimes completely disappeared (Fig. 2C and D). Such areas are junctions between layers with different organizations (i.e., cellulose microfibrils orientations, relative abundance of hemicelluloses and lignins). The fading of the staining by PATAg suggests that oxalate may change the reactivity of polysaccharides toward PATAg within the S2 layer. One can suggest that extraction or alteration of hemicellulose-rich compounds in the transition areas S1/S2 are at the origin of this apparent structural homogenisation of the S1/S2 layers. The biochemical analysis supports the hypothesis that polysaccharides are one of the targets of oxalate (see below).

Impact of oxalate treatment on poplar wood chips (TEM observations, PATAg): (A) and (C) chips treated by water; (B) and (D) chips treated by oxalate, as described in experimental section; note that no MSD destructuration was applied on the chips before impregnation (see experimental). The fading of PATAg staining is visible at the transition areas between S1 and S2 and S2 and S3 (A and B; arrows). The disappearance of the S3 layer was also observed in some cases (C and D; arrow). Scale bar: 1 μm. Masquer

Impact of oxalate treatment on poplar wood chips (TEM observations, PATAg): (A) and (C) chips treated by water; (B) and (D) chips treated by oxalate, as described in experimental section; note that no MSD destructuration was applied on the chips ... Lire la suite

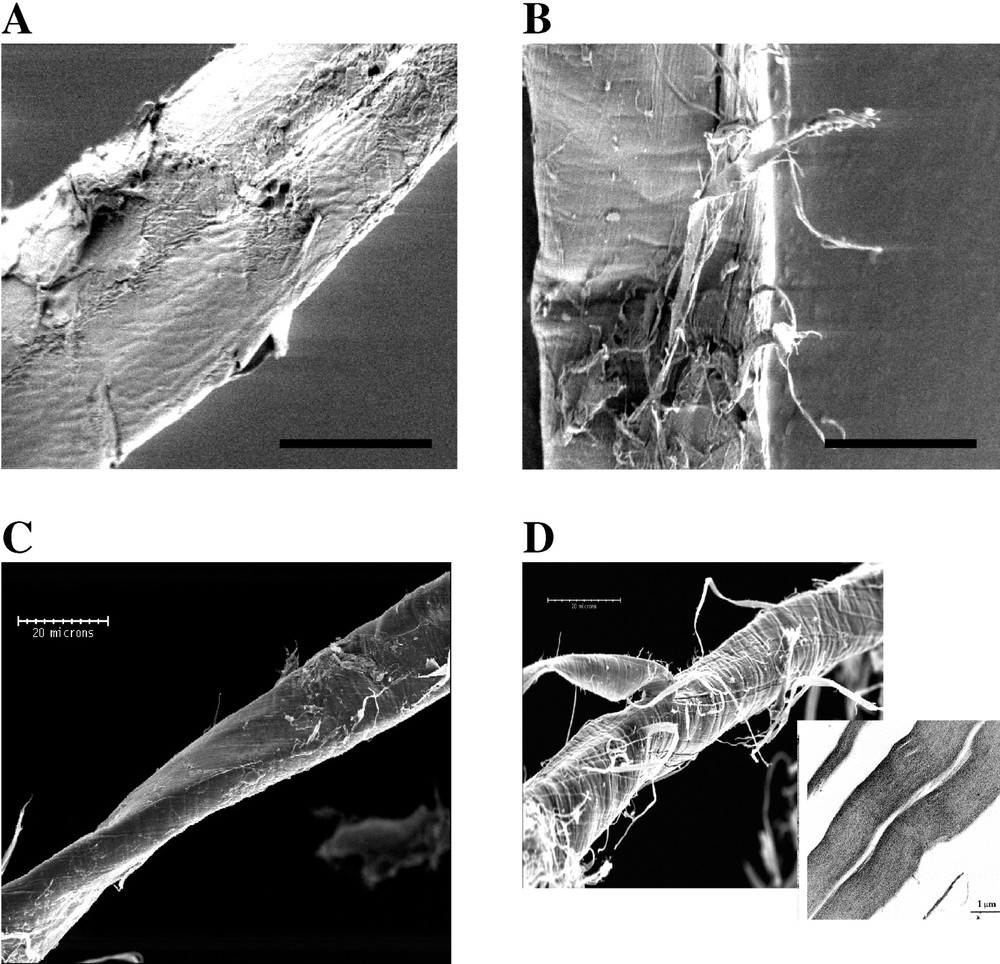

At the level of the fibres produced from oxalate-treated chips by the TMP process (Ox-TMP), an exfoliation of the S1 layer is observed in SEM, with the unmasking of the S2 layer, exposing its characteristic fibrillar and oriented organization, compared to the reference fibre produced from chips treated by water only (Fig. 3A and B). The observation of pulps refined at 100 ml CSF (Canadian Standard Freeness) shows an increased fibrillation of the S2 layers (Fig. 3C and D), accompanied with an internal fibrillation and delamination [9] (inset in Fig. 3D), not detected in the reference samples.

SEM observation of poplar fibres obtained by thermomechanical pulping after water (A and C) or oxalate (B and D) impregnation. (A) and (B): Fibres obtained after defibration; the surface of the water treated sample; (A) exhibits a typical smooth surface, indicating that rupture in the chips occurred between compound middle lamellae and the S1 layer; (B) the apparent ribbon-like structures removed from the surface of oxalate treated sample indicated that the rupture during TMP process was mainly between S1 and S2 or within the S2 layer. (C) and (D): Fibres refined at 100 ml CSF (Tappi-T-227 method); fibrillation is much more important in the oxalate-treated sample (D) than in the reference water-treated one (C). Inset (D): TEM picture showing internal fibrillation and delamination of the fibre (PATAg staining). All scale bars: 20 μm. Masquer

SEM observation of poplar fibres obtained by thermomechanical pulping after water (A and C) or oxalate (B and D) impregnation. (A) and (B): Fibres obtained after defibration; the surface of the water treated sample; (A) exhibits a typical smooth surface, ... Lire la suite

Thus, all these observations indicate that oxalate salts at pH 2.5 are modifying the cell-wall architecture. Among others, possible reactive sites would be the junction areas between the different layers composing the cell wall in poplar wood. Such modifications may affect either the mode of fibre separation from chips during an industrial thermomechanical (TMP) process, as shown by the different surface aspects of the obtained fibres, as well as the behaviour of the fibres during beating (internal delamination within the S2 layer and secondary fibrillation enhancement).

3.2 Chemical modifications of the cell-wall polymers by oxalate

Despite visual changes in chips' or fibres' ultrastructure related to the biochemical treatments, no lignin and polysaccharide removal could be quantified in wood sawdust nor in solid wood samples that have been treated by oxalate [6,10] (Table 1, data not shown, Gaudard and Kurek, unpublished); the only significant impact was a loss of xylose, arabinose and galactose, but on fibres issued from oxalate-treated chips (Table 1; Gaudard and Kurek, unpublished). Concomitantly, a slight increase (

Chemical composition of poplar wood chips, sawdust and fibres

| Poplar sawdust | Fibres originating from industrial poplar wood chips | ||

| Controla (mg g−1) | Controla (mg g−1) | Treatedb (mg g−1) | |

| Ligninc | 223.8 ± 4 | 245 | 246 (NS)d,e |

| Glucose | 471.2 ± 23 | 487 | 476 (NS) |

| Mannose | 19.1 ± 0.8 | 26 | 17.5 (S) |

| Xylose | 145.4 ± 7 | 157 | 135 (S) |

| Galactose | 42 ± 0.6 | 51 | 39 (S) |

| Pentosanf (Xyl+Ara) | Nd | 171 | 143 (S) |

a Sawdust or chips incubated in water;

b from chips treated by oxalate pH 2.5;

c acid insoluble lignins; see experimental section for the methods used;

d

NS: difference between treated and control samples not significant at

e

in this case, a significant

f xylose plus arabinose.

3.3 Modelling the action of oxalate on isolated cell wall components

The combination of microscopy and biochemical analysis suggests that non-cellulosic polysaccharides are one of the targets of oxalate in cell wall. To test further this hypothesis, we incubated solubilized birch xylans with oxalate salts (overnight incubation in a Na-oxalate buffer, pH 2.5). This leads to a 15–20% decrease of the viscosity [10]. Thus, xylan depolymerisation occurred and such effect could also take place within the cell wall, resulting in loosening of the polysaccharidic network. Considering that oxalic acid is a strong metal chelatant, binding of calcium from pectins may also loosen the cell-wall structure at the middle lamella–primary wall level accordingly [19,20].

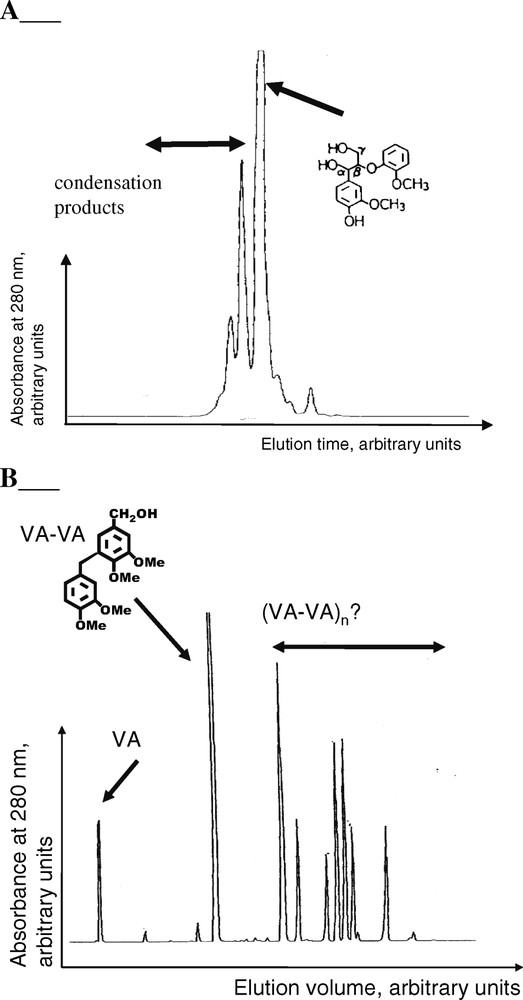

Another action of oxalic acid and/or Na-oxalate was also detected on lignin structures. Incubation of lignin model compounds of the G-G and G-S types in conditions close from that used for chips' treatments yielded a slight, but significant polymerisation of the dimers into oligomeric structures [10] (Fig. 4A). The reactivity of the non-phenolic monomer veratryl alcohol (VA; Fig. 1) was also tested. During its incubation at a more acidic pH (oxalic acid 100 mM;

Condensation of (A) lignin dimers (G-G) by Na-oxalate at pH=2.5 and of (B) veratryl alcohol (VA) by oxalic acid at pH<1.5 (refer to Fig. 1 for structures).

Condensation of (A) lignin dimers (G-G) by Na-oxalate at pH=2.5 and of (B) veratryl alcohol (VA) by oxalic acid at pH<1.5 (refer to Fig. 1 for structures).

3.4 Defibration of wood chips and properties of the fibres

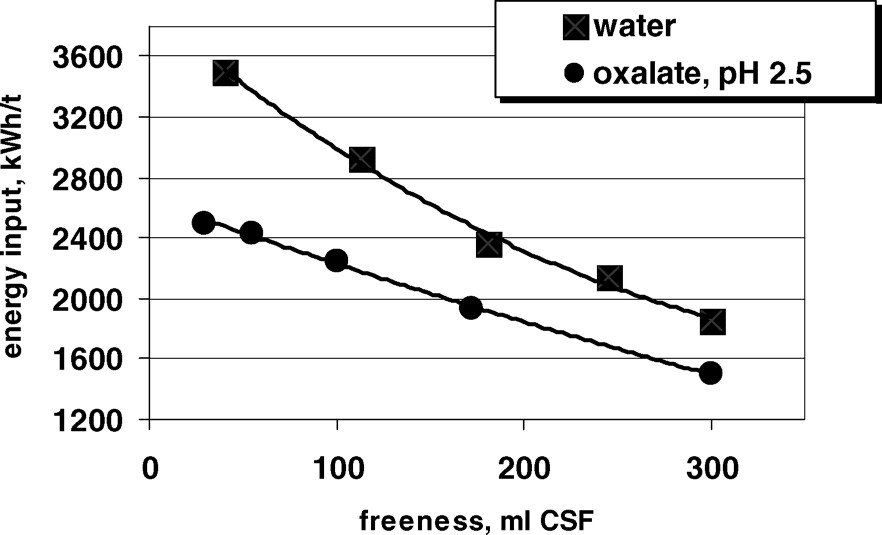

From a technical point of view, oxalate treatment of poplar wood chips resulted in a strong decrease of the total energy needed during defibration and refining processes (savings up to 1000 kWh t−1 at high freeness/low CSF index in the refining curve; Fig. 5).

Evolution of the energy consumption during the refining of poplar pulp (adapted from [9]); CSF: Canadian Standard Freeness.

The mechanical and optical properties of the resulting pulps were not altered nor really enhanced (Table 2). Statistical analysis reveal that differences are only significant at a low discriminatory level (

Properties of pulps produced from polar chips impregnated by water and by oxalate

| Treatmenta | Water | Oxalate |

| Tensile index (Nm g−1) | 21.0 | 19.1 (S)b |

| Tear index (mN m2 g−1) | 2.6 | 2.7 (S) |

| Breaking length (km) | 2.1 | 1.9 (S) |

| Brightness (% ISO) | 61.6 | 62.7 |

| Opacity (%) | 96.7 | 97.0 |

| k coefficient (m2 kg−1)c | 62.1 | 61.7 |

| s coefficient (m2 kg−1)d | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| Fibre length (mm) | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Fibre width (μm) | 32.6 | 33.8 (S) |

| Fibre curl (%) | 16.2 | 17.8 (S) |

| Coarseness (mg m−1) | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Shive content (%) | 2.1 | 1.9 (S) |

| Bulk (cm3 g−1) | 2.4 | 2.4 |

a All pulps were refined at 100 ml CSF;

b

S: difference relative to water-treated sample significant, but at

c light specific absorption coefficient;

d light scattering coefficient.

The main technical impact of the oxalate treatment of wood chips during TMP pulping is then the significant energy savings measured during the two critical defibration and refining steps. However, separate measurements indicated that the defibration energy remained essentially the same for oxalate- and water-treated chips, despite clear differences existing in the resulting fibre surfaces [10] (Fig. 3). The refining was however greatly facilitated as higher fibrillation extend at a same CSF point was reached with lower energy input. How to combine the energy savings with enhancement of the fibre properties is now the challenging technical question to solve.

4 Conclusions

The treatment of wood chips by oxalate leads to various modifications within the cell wall. The targets identified so far are the non-cellulosic polysaccharides (xylans). However, model compounds studies indicated that xylans depolymerisation might possibly occur simultaneously with some lignin condensations. All these reactions and modifications are leading to the energy savings obtained during the refining processes of the TMP pulps. However, the underlying mechanisms are not known for the moment. In particular, the in situ behaviour of the modified cell wall polymers after oxalate treatments under thermo-mechanical stress seems to be an important topic to address in the future [25,26].

Acknowledgments

This work was financed by the ‘Association nationale de la recherche technique’ (ANRT) and STORA–ENSO France through a PhD CIFRE thesis grant (V. Meyer). The authors wish also to thanks N. Durot (UMR FARE, INRA Reims), for the synthesis of the lignin dimers, and B. Cathala (UMR FARE, INRA Reims), for the RMN identification of the dimeric condensation products of veratryl alcohol.