1 Enzymes activated by monovalent cations

Since the discovery of the activating effect of K+ on pyruvate kinase, over 60 years ago [1], enzymes activated by monovalent cations have been identified abundantly in both the animal world and plants [2]. Renewed interest in this class of enzymes has been fostered by the recent availability of high-resolution crystal structures. Monovalent cation binding sites have been identified structurally in dialkylglycine decarboxylase [3,4], pyruvate kinase [5], thrombin [6], the molecular chaperone Hsc70 [7], fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase [8], S-adenosylmethionine synthetase [9], Trp synthase [10], coagulation factor Xa [11], branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase [12], methylamine dehydrogenase [13], fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase [14], Haemophilus influenzae HslV protein [15], ribokinase [16], activated protein C [17] and DNA mismatch repair protein MutL [18]. The monovalent cation-binding site of a catalytic RNA has also been described by X-ray crystallography [19]. Monovalent-cation-activated enzymes typically express optimal catalytic activity in the presence of K+, with the smaller cations Li+ and Na+ being less effective [2]. Enzymes activated by Na+ are less active in the presence of Li+ or K+ and are mostly confined to blood coagulation and the complement system. An interesting correlation exists between the preference for K+ or Na+ and the intracellular or extracellular localization of such enzymes, which suggests that monovalent cation activation is the result of evolutionary adaptation to environmental conditions.

Monovalent cations activate enzymes in essentially two ways: either by forming a ternary complex with enzyme and substrate, or allosterically. The two mechanisms are easily distinguishable. In the former case, the presence of the cation is absolutely required for catalytic activity; the cation is part of the substrate itself. In the latter case, the cation increases significantly the activity from a finite basal value by inducing a conformational change in the protein. Pyruvate kinase is an example of the former mechanism of monovalent cation activation. In this enzyme, K+ binds to the phosphate group of substrate and becomes an integral component of the substrate itself [5]. This mechanism is obeyed by all kinases that require K+ for optimal activity, with only one exception. Ribokinase is activated by K+ in an allosteric fashion through a conformational change of the protein [16] (Fig. 1). Unlike K+-activated enzymes, Na+-activated enzymes are fewer in number and feature exclusively allosteric activation. Thrombin, the key serine protease responsible for blood coagulation [20,21], vascular development and signaling [22–24], has emerged as the best characterized enzyme that uses Na+ as an allosteric activator [25] (Fig. 1). Na+ activation is also observed in other proteases involved in blood coagulation and the immune response, but not in digestive and degradative enzymes like trypsin and chymotrypsin [26]. Recent structural and mutagenesis data have revealed the molecular basis of thrombin allostery and features of this regulation that are relevant to the entire class of enzymes allosterically activated by monovalent cations.

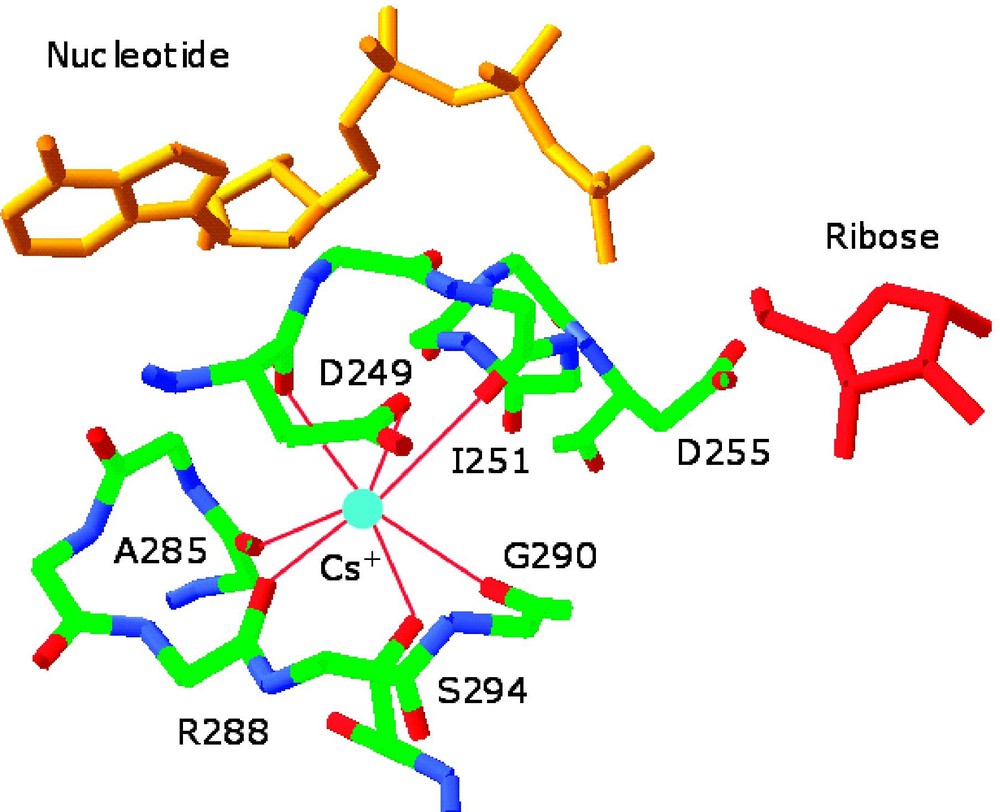

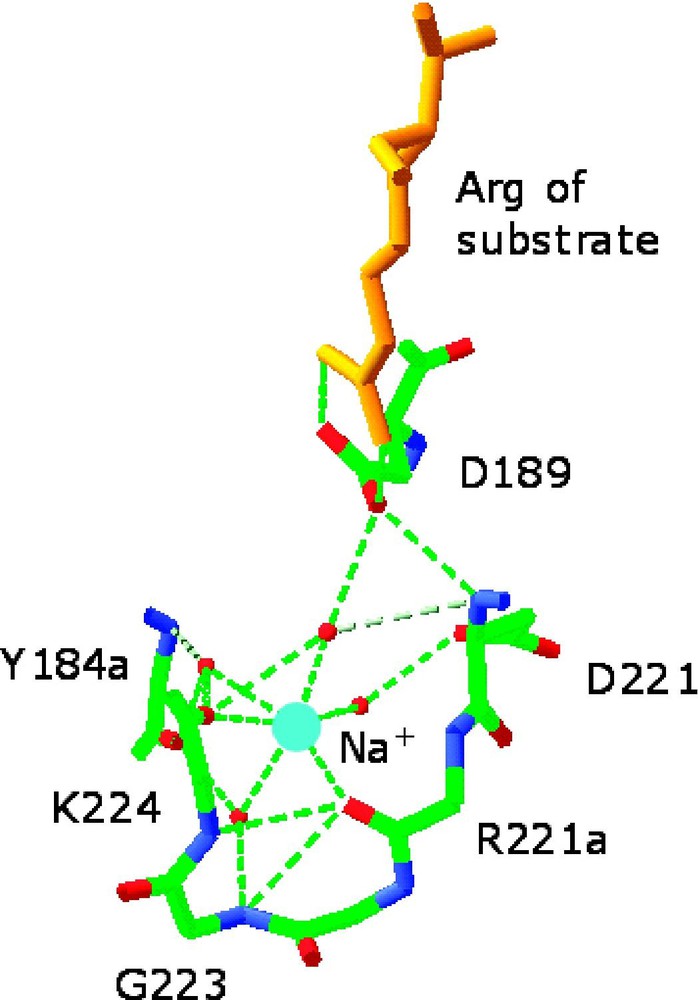

Environment of the monovalent cation-binding site in allosterically activated enzymes. (Left) Cs+ binding site of ribokinase (PDB entry 1GQT). Cs+ is represented as a cyan ball and is coordinated by the backbone O atoms of residues 285, 288, 290, 251, and 249 and by the side chains of Asp-249 and Ser-294. H-bonds are depicted by red lines. Cs+ is a structural and functional mimic of K+ for this enzyme. Note the close proximity of the Cs+ binding site to the 252–255 region that defines the anion hole of the active site where ribose (red) and nucleotide (orange) come together. Asp-255 is placed for optimal interaction with the γ-phosphate of the nucleotide and its orientation can be influenced allosterically by Cs+ binding. Other effects can be propagated from the Cs+ binding site to the active site lid when ribose is bound [16]. (Right) Na+ binding site of thrombin (PDB entry 1SFQ). Na+ is represented as a cyan ball, and is coordinated octahedrally by four water molecules (red balls) and the backbone O atoms of residues 221a and 224. The side chain of Asp-189 couples electrostatically to the guanidinium group of the Arg residue of substrate at P1 (orange) and H-bonds to one (denoted by *) of four water molecules in the Na+ coordination shell. H-bonds are shown by broken lines in green [33]. Masquer

Environment of the monovalent cation-binding site in allosterically activated enzymes. (Left) Cs+ binding site of ribokinase (PDB entry 1GQT). Cs+ is represented as a cyan ball and is coordinated by the backbone O atoms of residues 285, 288, 290, 251, ... Lire la suite

2 Allosteric activation of thrombin by Na+

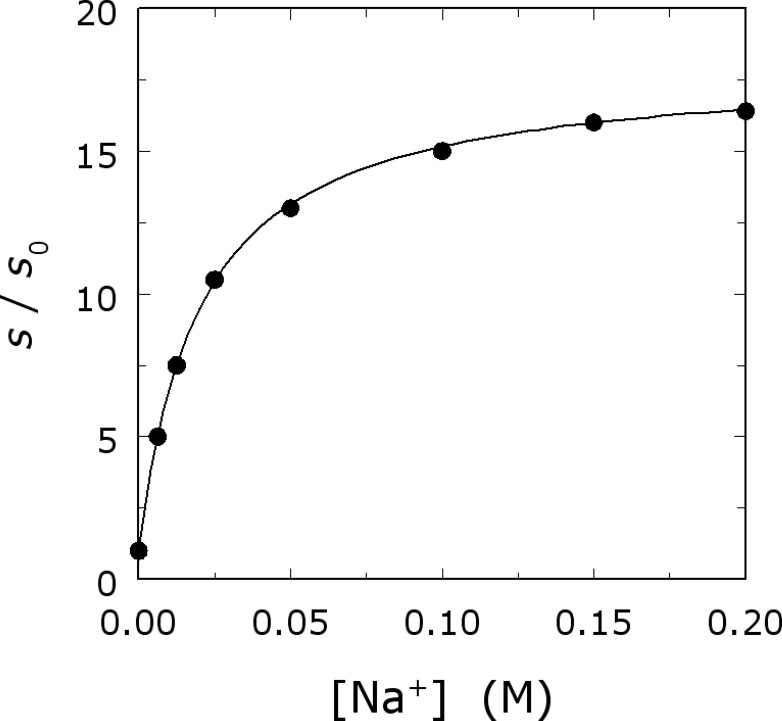

The kinetic signatures of allosteric activation by monovalent cations are easy to detect experimentally. When the value of

| (1) |

Na+ activation of thrombin. Shown is the value of

In the case of thrombin and serine proteases in general, the Michaelis–Menten constants s and

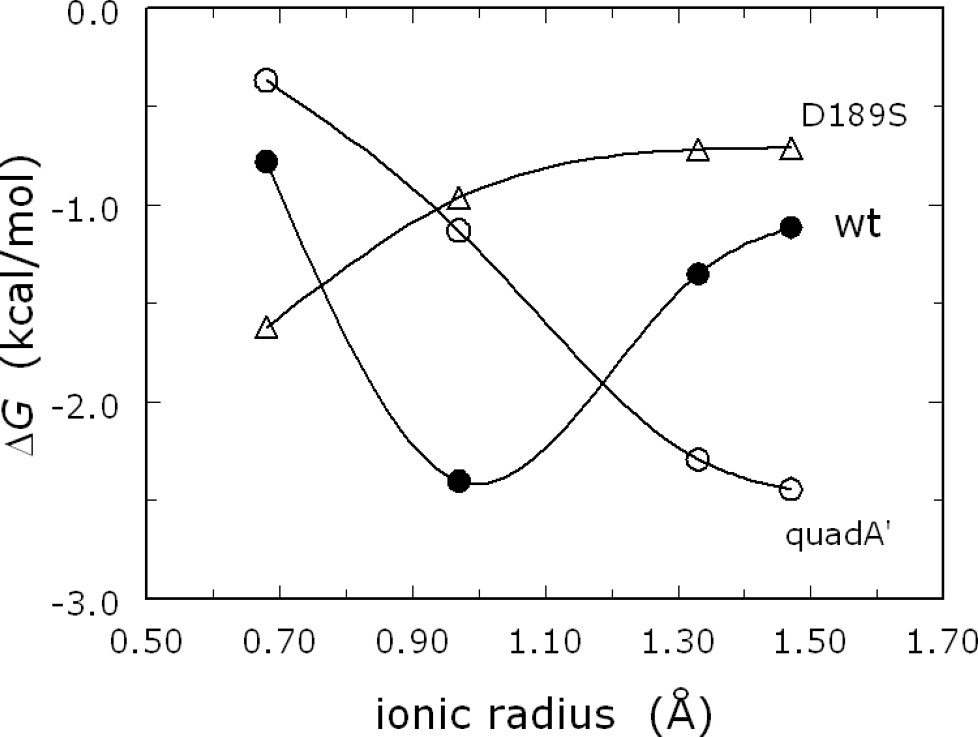

Measurements of s in the presence of different monovalent cations, at the same ionic strength, reveal that thrombin is activated preferentially by Na+. Measurements of monovalent cation binding also demonstrate a preference for Na+ over the larger cation K+ or the smaller cation Li+ (Fig. 3) [29]. The structure of thrombin has therefore been optimized for preferential binding of Na+ and for allosteric transduction of Na+ binding into enhanced catalytic activity. The cation selectivity seen in thrombin and monovalent-cation-activated enzymes is reminiscent of that featured by ion channels. It is therefore remarkable that such selectivity can be redesigned by rational engineering. Indeed, thrombin can be converted into a K+-specific or Li+-specific enzyme by site-directed mutagenesis [29,30] (Fig. 4). The thermodynamic signatures of Na+ binding are noteworthy. The ionic-strength dependence of Na+ binding to thrombin shows only a small effect, but the temperature dependence shows a marked curvature in the van't Hoff plot, conducive to a large and negative heat capacity change [30,31]. This peculiar temperature dependence is also observed for K+ binding to thrombin [30] and for Na+ binding to activated protein C [32].

Monovalent cation binding curves of thrombin determined from changes in intrinsic fluorescence as a function of cation concentration [M+], under experimental conditions of: 5 mM Tris, 0.1% PEG8000, pH 8.0 at 10 °C, I=800 mM. Data are expressed as fractional changes of the value of fluorescence to enable direct comparison. Continuous lines were drawn using the expression

Monovalent cation binding curves of thrombin determined from changes in intrinsic fluorescence as a function of cation concentration [M+], under experimental conditions of: 5 mM Tris, 0.1% PEG8000, pH 8.0 at 10 °C, I=800 mM. Data are expressed as fractional changes ... Lire la suite

Monovalent cation specificity profile for wild-type thrombin (●) and the mutants quadA′ (○) and D189S (▵). Shown are the values of the binding free energy

Monovalent cation specificity profile for wild-type thrombin (●) and the mutants quadA′ (○) and D189S (▵). Shown are the values of the binding free energy

3 Structural basis of thrombin allostery

Binding of Na+ to thrombin promotes substrate binding (higher

The Na+ binding site of thrombin is strategically located in close proximity to the primary specificity pocket [6] (Fig. 1), nestled between the 220- and 186-loops that contribute to substrate specificity in serine proteases [34–36]. The Na+ binding sites of coagulation factor Xa [11] and activated protein C [17] are similarly located and arranged structurally. The location of the Na+ binding site away from residues of the catalytic triad or involved directly in substrate recognition underscores the allosteric nature of the activation observed experimentally. The bound Na+ is coordinated octahedrally by two backbone O atoms from the protein residues Arg-221a and Lys-224 and four buried water molecules anchored to the side chains of Asp-189, Asp-221 and the backbone atoms of Gly-223 and Tyr-184a (Fig. 1).

Extensive Ala-scanning mutagenesis of thrombin has revealed the ‘allosteric core’ of residues energetically linked to Na+ binding [33]. Practically all residues of the allosteric core cluster around the Na+ site. Na+ binding is severely compromised (>30-fold increase in

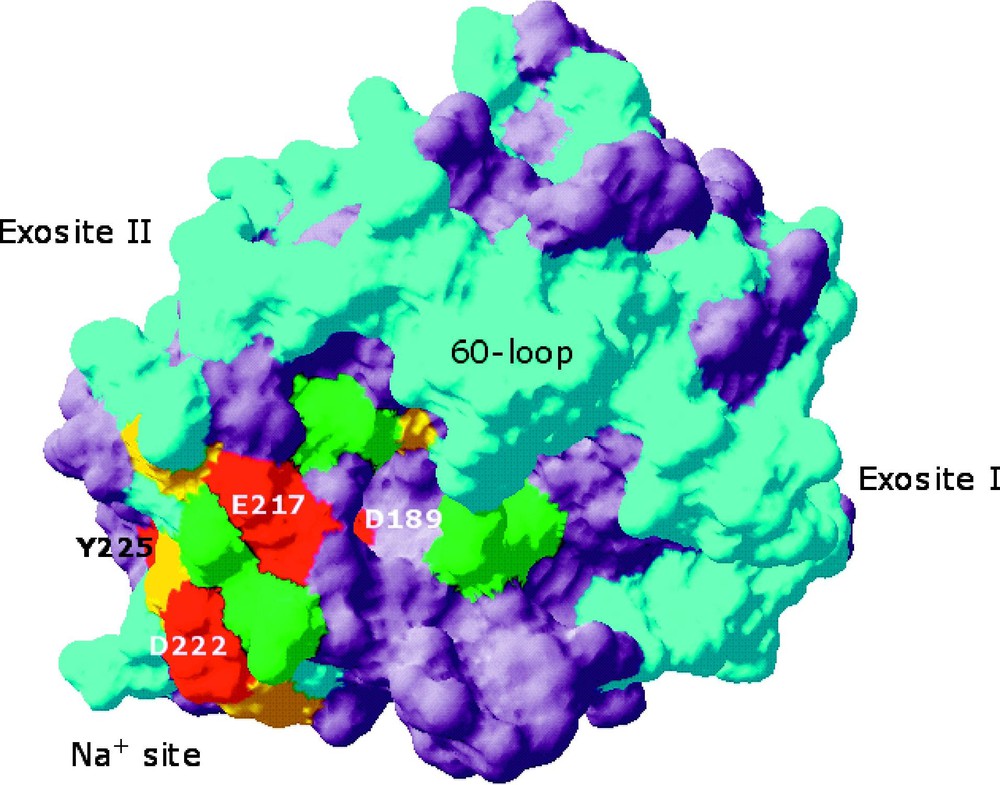

Space-filling model of thrombin depicting the structural organization of the allosteric core [33]. Residues affected by Ala replacement are color-coded based on the log change in the

Space-filling model of thrombin depicting the structural organization of the allosteric core [33]. Residues affected by Ala replacement are color-coded based on the log change in the

The Ala-scanning mutagenesis screen of thrombin has also revealed residues important for allosteric transduction (the parameter α in Eq. (1)). Asp-189 and Asp-221 are key residues promoting substrate binding to the Na+-bound form and hence allosteric transduction. Asp-189 is part of the allosteric core and defines the primary specificity of the enzyme by coordinating directly the guanidinium group of Arg at P1 of substrate. Asp-221 is a crucial component of the Na+ binding site (Fig. 1), with its side chain anchoring one of the four water molecules ligating Na+ and also H-bonding to Asp-189. Mutation of Asp-221 does not affect Na+ binding, but almost abrogates the Na+-induced enhancement of substrate hydrolysis. This finding is a direct confirmation of the independence of the parameters in Eq. (1) and the fact that they are controlled by distinct structural determinants.

The allosteric core defined by mutagenesis data suggests that Na+ binding to thrombin influences residues in the immediate proximity to the cation binding site, namely Asp-189, Glu-217, Asp-222, and Tyr-225. Other residues making contacts with the ligating water molecules in the coordination shell are Tyr-184a, Asp-221, and Gly-223 and their mutation to Ala affects Na+ binding > 10-fold (Tyr-184a, Gly-223), or affects the allosteric transduction of this event into enhanced catalytic activity (Asp-221). How does Na+ binding to thrombin affect these residues? The structures of the Na+-free and Na+-bound forms are highly similar overall, but there are five notable differences that help explain the kinetic and thermodynamic signatures of Na+ binding to thrombin. These differences influence (Fig. 6): (1) the Arg-187:Asp-222 ion-pair, (2) the orientation of Asp-189 in the primary specificity pocket, (3) the orientation of Glu-192 at the entrance of the active site, (4) the orientation of the catalytic Ser-195, and (5) the architecture of the water network spanning >20 Å from the Na+ site to the active site.

Structural changes induced by Na+ binding to thrombin depicted by the structures of the Na+-free (red, PDB entry 1SGI) and Na+-bound (yellow, PDB entry 1SG8) forms [33]. The changes explain the kinetic and thermodynamic signatures linked to Na+ binding. The main changes induced by Na+ (blue ball) binding are: formation of the Arg-187:Asp-222 ion-pair that causes a shift in the backbone O atom of Arg-221a, reorientation of Asp-189, shift of the side chain of Glu-192, and shift in the position of the Oγ atom of Ser-195. Also shown are the changes in the water network connecting the Na+ site to the active site Ser-195. The water molecules in the Na+-bound form (yellow balls) are organized in a network that connects Na+ to the side chain of Asp-189 and continues on to reach the Oγ atom of Ser-195. A critical link in the network is provided by a water molecule (*) that H-bonds to Ser-195 and Glu-192. This water molecule is removed in the Na+-free form, causing a reorientation of Glu-192. The connectivity of water molecules in the Na+-free form (red balls) is further compromised by the lack of Na+ and proper anchoring of the side chain of Asp-189. H-bonds are shown by broken lines and refer to the Na+-bound form. Masquer

Structural changes induced by Na+ binding to thrombin depicted by the structures of the Na+-free (red, PDB entry 1SGI) and Na+-bound (yellow, PDB entry 1SG8) forms [33]. The changes explain the kinetic and thermodynamic signatures linked to Na+ binding. ... Lire la suite

The Arg-187:Asp-222 ion-pair connects the 220- and 186-loops that define the Na+ site. Asp-222 belongs to the allosteric core and the mutant D222A has drastically impaired Na+ binding, a property mirrored to smaller extent by the R187A mutant. The ion pair breaks when Na+ is released, bringing about a concomitant shift in the backbone O atom of Arg-221a that directly coordinates Na+. In the Na+-bound form, Asp-189 is optimally oriented for electrostatic coupling with the P1 Arg residue of substrate, but its orientation changes slightly when Na+ is released. The change reduces the affinity toward substrate and offers an explanation for the reduced

The structural changes observed at the level of Asp-222, Asp-189 and Ser-195 offer a plausible explanation for the reduced substrate binding and conversion in the Na+-free form. However, these residues are distant in space and the hallmark of allosteric proteins is the ability to couple structural domains that are separated. In thrombin, the communication between the Na+ site, Asp-189 and Ser-195 requires a network of linked processes that span more than 20 Å. Remarkably, this network is provided by a cluster of H-bonded water molecules that embed the Na+ site, the primary specificity pocket and the active site (Fig. 6). Na+ binding organizes a network of eleven water molecules that connect through H-bonds up to side chain of Ser-195. These water molecules act as links between the strands 215–219, 225–227 and 191–193, that define the Na+ site and the walls of the primary specificity pocket, and fine-tune substrate docking into the active site. In the Na+-free form, only seven water molecules occupy positions in the network equivalent to those seen in the Na+-bound form and the connectivity is radically altered. The change in the number and long-range ordering of water molecules linked to Na+ binding offers an explanation for the large and negative heat capacity change measured upon Na+ binding to thrombin. The change is the result of the formation of water binding sites connecting strands and loops of the Na+ site, by analogy to what is observed when water molecules are buried at the Trp repressor–operator interface [38]. The allosteric properties of thrombin depend on the structure of this water network in a decisive manner. All residues involved energetically in Na+ binding and the allosteric transduction of this event into enhanced catalytic activity are in direct contact with water molecules in the network. The network provides the long-range connectivity needed to allosterically communicate information from the Na+ site to the active site Ser-195 and to residues involved in substrate recognition, like Asp-189 and Glu-192.

The structural changes underlying Na+ binding are small, but appear at critical locations within the protein. Other monovalent-cation-activated enzymes investigated structurally to date [3–5,7,8,10,16] show conformational changes induced by cation binding that are small, but of extreme functional relevance. In the case of dialkylglycine decarboxilase, the effect of Na+ on the enzyme is mediated by the reorientation of a Ser residue near the active site induced by cation binding [3,4]. In the case of ribokinase, K+ binding influences allosterically the orientation of Asp-255 in the anion hole of the active site [16]. In the case of Trp synthase, binding of Na+ triggers small local and long-range changes in quaternary structure [10]. In other allosteric systems, like transmembrane receptors, subtle conformational changes as small as 1 Å are transmitted from ligand-binding sites to effector sites over distances greater than 100 Å using H-bonding networks [39,40]. The strategy chosen by thrombin to accomplish the Na+-mediated allosteric control of substrate binding and catalysis is consistent with the mechanisms exploited by other allosteric enzymes: long-range communications mediated by H-bonding networks are linked to small side-chain rearrangements that result in significant changes in substrate binding and catalysis. The strategy suits well the rigidity of the scaffold available to serine proteases, where most of the flexibility resides in peripheral loop regions connecting strands of the rigid β-barrel core.

4 Role of Na+ in blood coagulation

Thrombin plays two important and paradoxically opposing functions in the blood [41]. It acts as a procoagulant when it converts fibrinogen into an insoluble fibrin clot that anchors platelets to the site of lesion and initiates processes of wound repair. This action is reinforced and amplified by activation of the transglutaminase factor XIII that covalently stabilizes the fibrin clot, the inhibition of fibrinolysis, and the proteolytic activation of factors V, VIII and XI [20]. In addition, thrombin acts as an anticoagulant when it activates protein C [42]. This function unfolds upon binding to thrombomodulin, a receptor on the membrane of endothelial cells. Binding of thrombomodulin suppresses the ability of thrombin to cleave fibrinogen and PAR1, but enhances >1000-fold the specificity of the enzyme toward the zymogen protein C. Activated protein C cleaves and inactivates factors Va and VIIIa, two essential cofactors of coagulation factors Xa and IXa that are required for thrombin generation, thereby down regulating both the amplification and progression of the coagulation cascade. In addition, thrombin is irreversibly inhibited at the active site by the serine protease inhibitor antithrombin with the assistance of heparin [43,44]. Other important effects are triggered by thrombin upon cleavage of protease-activated receptors (PARs), which are members of the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Four PARs have been cloned and they all share the same basic mechanism of activation [24]: thrombin cleaves within the extracellular domain to expose a new tethered ligand domain that folds back and activates the cleaved receptor [23]. Activation of PAR1 and PAR4 on human platelets triggers platelet activation and aggregation and unfolds the prothrombotic role of thrombin in the blood.

How does Na+ binding influence the plethora of thrombin interactions in the blood? Under physiologic conditions of [Na+] (140 mM), pH and temperature, the

The structural changes observed in the Na+ bound form of thrombin, relative to the Na+-free form (Fig. 6) are conducive to a conformation that is more prone to interact with substrate and explain why Na+ binding optimizes thrombin for its procoagulant, prothrombotic and signaling functions [45,46,58]. The orientation of Glu-192 in the Na+-free form, however, compensates for the deleterious changes around Asp-189 and Ser-195 and reduces the electrostatic clash with the acidic residues at position P3 and P3′ of protein C. That results in a conformation that retains activity toward protein C and explains the intrinsic anticoagulant nature of the Na+-free form [45,46,58].

5 Na+ binding and the evolution of serine proteases

Recent progress in the study of Na+ binding to thrombin has revealed the underpinnings of the structural and functional components of the interaction. There is, however, an intriguing aspect of the Na+ activation of thrombin and related serine proteases that has contributed to our understanding of the evolution of these enzymes. Signatures of watershed events linked to evolutionary transitions in protein families can be identified from sequence comparisons and analysis of amino acid occurrences at any given position along the sequence. Evolutionary markers can be defined as dichotomous choices at given amino acid positions mapping to codons that cannot interconvert by single nucleotide mutations [61,62]. Because of their very nature, such markers identify decisive evolutionary transitions. Analysis of over 600 sequences of serine proteases of the chymotrypsin family, to which thrombin belongs, returns codon usage dichotomies only at three positions, namely residues 195, 214, and 225 [61].

The sequence dichotomies used to categorize chymotrypsin-like proteases are TCN (N = any base) or AGY (Y = C or T) codon usage for the active site nucleophile Ser-195, TCN or AGY codon usage for the highly conserved Ser-214, which is adjacent to the active site, and Pro or Tyr usage for residue 225, which determines whether a chymotrypsin-like protease can undergo catalytic enhancement mediated by Na+ binding [26]. Na+ binding requires Tyr-225 (or Phe-225) because Pro-225 reorients the backbone O atom of residue 224 (Fig. 1) in a position incompatible with Na+ coordination [26,37]. Primordiality of TCN compared to AGY and of Pro compared to Tyr establishes the relative ages of the lineages with respect to each other. Thus, Ser-195:TCN/Ser-214:TCN/Pro-225 is the most primordial marker configuration, and Ser-195:AGY/Ser-214:AGY/Tyr-225 is the most modern [61]. Profiling of selected proteases involved in a number of physiologically relevant processes reveals the evolutionary transition among these processes (Table 1). Notably, the most primordial proteases are engaged in degradative processes, with trypsin, chymotrypsin and elastase being the best-known examples. Changes in the molecular markers start to appear with the developmental proteases of the fruit fly or with the fibrinolytic proteases. Interestingly, the pressure to change residue 225 to a Na+ accommodating residue like Tyr or Phe first emerged with developmental proteases. It is with the complement system that pressure to mutate the molecular markers becomes conspicuous. The complement appears as an evolutionary battleground for such markers: factors in the alternative pathway retain Pro-225, but factors in the lectin and classical pathways show pressure to introduce Na+ binding. It is well known that the alternative pathway predated the lectin and classical pathways [63,64]. Interestingly, within the deuterostome lineage that gave rise to the vertebrates, the ancestor of complement factor B found in the sea urchin has Tyr-225, with Ser-195:TCN/Ser-214:AGY. It is in the sea urchin, where a primitive complement system only included the ancestors of factor B, C3 and MASP, that evolution started to explore alternative codons for Ser-214 and Na+ binding residues like Tyr-225. That trend is revealed eloquently in the vertebrates MASPs and the classical pathway proteases C1r and C1s. The final stage of transition for the codons is witnessed in the blood coagulation system that evolved as a specialization of the classical pathway of the complement. The proteases of blood coagulation are clearly split into two groups, with factors XI and XII showing a distinct codon usage for Ser-195 and Ser-214 compared to the vitamin K-dependent factors VII, IX, X, prothrombin and protein C. Factors XI and XII therefore evolved from a different lineage compared to the other clotting factors [65]. However, an important difference in the codon usage of Ser-214 is seen between prothrombin and the other vitamin K-dependent factors. Prothrombin appears to be more ancestral and of a different evolutionary origin compared to the other vitamin K-dependent factors. Indeed, prothrombin possesses kringle domains and not EGF domains, whereas all other vitamin K-dependent clotting proteases possess EGF domains but not kringles. Although changes in such auxiliary domains through exon shuffling were quite common during evolution [66] and it is not possible to conclusively specify a chronology for such changes, it is tempting to speculate that prothrombin predated all other coagulation factors and was recruited in the coagulation cascade from another system, possibly involved in immune response. The similarity of marker profiles between prothrombin, MASP-2, C1r and C1s is particularly striking.

Segregation of function and evolutionary markers in serine proteases. Proteases are color-coded based on their evolutionary distance from the ancestral Ser-195:TCN/Ser-214:TCN/Pro-225 marker profile as cyan (one marker change), yellow (two marker changes), or red (three marker changes). All proteases are human, except developmental that are from fruit fly. Markers are color-coded based on their chronology as red (ancient) or blue (modern). *Human complement factors B and C2 have an insertion in the 220 region that makes identification of residue 225 ambiguous. Listed are the residues located twelve positions upstream of the highly conserved Trp-237

Evolutionary markers trace the origin of Na+ binding to serine proteases within the complement system along the deuterostome lineage and within the developmental proteases along the protostome lineage (Table 1). Perhaps the need for Na+ binding emerged independently during evolution along the two main branches of the animal kingdom [67]. Alternatively, Na+ binding might have emerged much earlier, before the protostome–deuterostome split, which traces back to the flat worms. Allosteric activation by Na+ in serine proteases is likely quite ancient and certainly predated vertebrates and the onset of sophisticated mechanisms of defense, like immunity and blood clotting.

Why was Na+ binding deemed beneficial during evolution? Perhaps a way to address this key question is to identify the environments or conditions where Na+ binding would be beneficial. A simple scenario portrays the ancestral Na+-activated enzyme in an environment low in Na+, perhaps inside the cell. Such enzyme could have been activated upon injury caused to the cell and exposure to an extracellular environment rich in Na+, perhaps seawater. Activation of the enzyme could have been linked to repair of the injury. Indeed, there is circumstantial evidence that the cytoplasm of certain algae undergoes a sol → gel transition at the site of puncture of the cell, as though a Na+-activated intracellular protease were at work [68]. It is also possible that the ancestral Na+-activated enzyme would have worked in an environment where the Na+ concentration was subject to change, so that different levels of activity would be expressed at different time or space locations. Such scenario could have existed during development of primordial organisms exploiting Na+ concentration gradients. Although these hypotheses are difficult to prove conclusively, they bring attention to Na+ activation as being closely intertwined with the evolution of defense mechanisms or development. This is exactly where current sequence data identify Na+-activated serine proteases (Table 1).

6 Conclusions

The allosteric activation of thrombin by Na+ is a mechanism of regulation of enzyme activity and specificity of enormous physiologic importance. The mechanism is present in other clotting enzymes and enzymes involved in immune response and embryonic development. Mutagenesis and structural investigation of this mechanism has recently revealed the details of how Na+ binding is transduced into enhanced substrate binding and catalytic activity. Residues responsible for cation recognition and allosteric transduction have been identified by site-directed mutagenesis. The information can now be used to explore other Na+-activated enzymes along the same lines, or to offer comparisons with the mechanism of K+ activation in kinases. Redesigning monovalent cation specificity in proteins, or engineering monovalent cation activation have also become realistic goals because of the knowledge emerged from the studies on Na+ binding to thrombin. The discovery of evolutionary markers that facilitate the definition of paths of descent within protein families indicates that the introduction of Na+ binding was a watershed event in serine protease evolution, which likely predated the protostome–deuterostome split.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by NIH research grants HL49413, HL58141, and HL73813.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier