1 Introduction

Parnassius apollo L. (Lepidoptera, Papilionidae) is a species of steppe origin, with plenty of subspecies and races. Some of them underwent decline or became extinct during the last several decades [1]. Parnassius apollo ssp. frankenbergeri Slabý inhabiting the Pieniny Mts (southern Poland) has avoided this threat only due to a recovery plan initiated in 1991 (see [1] for detailed references).

Larvae of Apollo butterfly from the Pieniny Mts were considered as oligophagous, since in natural conditions they were observed feeding on Sedum telephium ssp. maximum and Sempervivum soboliferum [2]. Since S. telephium is preferred as a food-plant, this subspecies falls into a ‘telephiophagous’ trophic group, together with other Carpathian, as well as Scandinavian and Balkan forms [3]. According to Pekarsky, the ‘albophagous’ group of P. apollo, inhabiting the Alps and southwestern Europe, shifted from S. telephium to S. album because of the disappearance or shortage of the former food-plant in their biotopes as the result of long-term climatic changes. Further observations supported this hypothesis: it has been noticed that ‘telephiophagous’ larvae and imagoes are larger than ‘albophagous’ ones [2]. Moreover, larvae of alpine ‘albophagous’ subspecies that fed on S. telephium were larger and their development was faster than on native S. album [4]. Recent experiments on P. apollo ssp. frankenbergeri showed that this subspecies is a monophage only successfully developing on S. telephium [1].

Analysis of the chemical contents of S. telephium has revealed the presence of organic acids, amino acids and carbohydrates in its aboveground parts [5]. Further phytochemical studies showed low contents of organic substances (app. 8% wet weight of leaves) and the presence of secondary compounds, mainly various phenolic acids (also as glycosides), and small amounts of non-phototoxic coumarins. There were no alkaloids, cyanogenic glycosides or their derivatives [6]. Phenolic acids are known as feeding deterrents, hardly ever as attractants or nutrient source [7]. Phenolic compounds and coumarins seem to constitute the plant defence system, although no clear changes of their concentrations have been stated so far during the vegetation period or in the response to larval feeding [6]. On the other hand, in natural conditions larvae eat no more than about 30% of the leaves of the single plant, then move to another one [8]. It has also been found that rearing P. apollo on artificially cultivated orpine (in changed photoperiod) resulted in digestion disturbances and increased larval mortality [9,10].

A last-instar Apollo larva in hyperphagic phase consumes about 2 g of plant tissues daily, which contain 20–50 μg of phenolic acids [6]. This relatively fast chyme passage trough its alimentary tract may be the adaptation to the presence of the secondary compounds in the food plant. Such a response can diminish harmful effects of allochemicals, but simultaneously may decrease nutrients availability, particularly amino acids from the plant proteins.

Adaptation of a herbivore digestive system to a specific food source involves a synthesis of an appropriate set of digestive enzymes [11], regulation of their excretion [12] and maintenance of alkaline condition in the midgut lumen (pH between 9.5–12) [13]. These species-specific changes must ensure obtaining sufficient amounts of necessary nutrients to complete the feeding stage of development [12]. The critical aspect in proteins digestion is the release of exogenous amino acids (e.g., arginine, lysine, and few others) necessary for the synthesis of wide arrays of structural and functional proteins [14]. Broadway has shown that the trypsin:chymotrypsin ratio determines the protein-digestion strategy of an insect. When larvae use only trypsin as endoprotease, their growth is positively correlated with the amount of arginine and lysine in the ingested proteins. A set of endoproteases enables faster and more effective proteins digestion. Hence, larvae of oligophagous Pieris rapae (Pieridae), with relatively high protein requirements and limited food sources, use different endoproteases (trypsin:chymotrypsin ratio 1:1), in comparison with polyphagous Trichoplusia ni (Noctuidae) larvae, which have a very low chymotrypsin activity (trypsin:chymotrypsin ratio 3:1) [15].

So far, studies on lepidopteran proteolytic enzymes have focused mainly on their activities in pest species. The current leading issues are: enzyme inhibition [16–18] with respect to plant protease inhibitors [19,20], determination of the primary protein structure, nucleotide sequence in a corresponding gene [21], and the effects of plant anti-nutritional substances on larval growth of the pests [22].

These investigations, aimed primarily at developing effective biological methods of pests' control, have never been applied to disappearing species like Parnassius apollo. The preliminary description of the proteolytic activity in Apollo larvae is the goal of this study. This paper continues our earlier contribution to the digestive strategy in this species [23].

2 Materials and methods

The larvae of Parnassius apollo ssp. frankenbergeri Slabý originated from a semi-natural open-field breeding colony, set up in the Pieniny National Park, for a recovery plan in the Pieniny Mts. Following the permission of the Polish Ministry of Environment, the individuals for enzymatic analyses were obtained from eggs collected in the preceding year. The fourth (L4) and fifth (L5) instar larvae were randomly chosen from the stock colony. Additionally L5 larvae were divided into two subgroups (‘young’ and ‘hyperphagic’), as previously described [23]. For enzymatic assays, two samples from each individual were obtained: midgut tissue with glicocalyx (MT), and liquid gut contents with peritrophic membrane (MC).

The optimal pH for selected proteases (total proteolytic (caseinolytic) activity, trypsin and aminopeptidase) was assessed using 0.1 M phosphate (pH 5.8–7.8), 0.05 M Tris-maleate (pH 5.8–7.8), 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4–9.0) and 0.1 M glycine–NaOH (pH 8.6–10.6) buffers. The ionic strength of the buffers was adjusted according to the methods described for other Lepidoptera (see Table 1 for references). The incubation temperature for all the assays was 30 °C. Moreover, the temperature-dependent response for trypsin activity was determined.

Assay conditions and methods used in the determination of proteases

| Enzyme | Substrate | Buffer for substrate | Homogenate volume [μl] | Incubation [min] | Termination | Further procedures | Final vol. [ml] | Final product | λ [nm] | Comments | References |

| Total proteolytic (caseinolytic) activity | 50 μl 1% azocasein | glycine–NaOH: 0.1 M, pH 9.8 | 50 | 30a or 60b | 0.5 ml 8% TCA | 5 min of precipitation of azocasein fragments; centrifugation at 8000×g, 10 min | 0.6 | azopeptides | 366 | measurement until 10 min | [24,25] |

| Trypsin | 3 ml 1 mM B-R-pNA in 15% DMF | glycine–NaOH: 0.1 M, pH 10.4, 20 mM CaCl2 | 50 | 30b or 45a | 0.6 ml 20% acetic acid | – | 3.65 | nitroaniline | 410 | measurement after 30 min; |

[26,27] modified after [17,28] |

| Chymotrypsin | 3 ml 1 mM G-F-pNA in 10% DMF | glycine–NaOH: 0.1 M, pH 10.6, 20 mM CaCl2 | 50 | 60 | 0.6 ml 20% acetic acid | – | 3.65 | ||||

| 0.6 ml 0.25 mM Suc-AAPF-pNA in 10% DMF | 10 | 60a or 30b | 0.12 ml 20% acetic acid | – | 0.73 | ||||||

| Aminopeptidase | 3 ml 1 mM L-pNA in 10% DMF | Tris-HCl: 0.05 M pH 9.0, 5 mM |

50 | 15a (30a) or 60b | 0.6 ml 20% acetic acid | – | 3.65 | nitroaniline | 410 | measurement after 30 min; |

[26,29] modified after [28] |

| Carboxypeptidase A | 0.5 ml 1 mM N-CBZ-V-L | Tris-HCl: 0.05 M pH 9.0, 0.1 M NaCl | 50 | 15a (30a) or 60b | 1.5 ml acetate buffer: 0.4 M, pH 5.0 | 2 ml ninhydrin reagent, 30 min at 100 °C, chilling, 6 ml 50% ethanol | 10.05 | amino acids | 570 | measurement after 20–30 min | [30–32] modified after [11] |

a MT (midgut tissue);

b MC (liquid midgut content).

The applied colorimetric procedures and used substrates are summarized in Table 1. Protein concentrations were determined according to Bradford [33]. Due to the limited number of individuals for the planned analyses, an enzymatic assay for each sample was duplicated and the obtained mean was taken for further calculations.

Common names of enzymes were simplified according to the last review of Terra and Ferreira [34]. Despite some functional differences between insect and vertebrate endopeptidases, the authors use ‘trypsin’ and ‘chymotrypsin’ instead of ‘trypsin-like’ and ‘chymotrypsin-like’, respectively. In a previous paper, they used both names interchangeably [35].

Statistical analyses were performed with ANOVA/ MANOVA, and T Tukey's test for unequal sample size was applied for a post hoc analysis. Test t for dependent variables was used to estimate the significant differences between the samples containing the midgut tissues (MT) or the liquid gut contents (MC) in the same larval instar (

3 Results

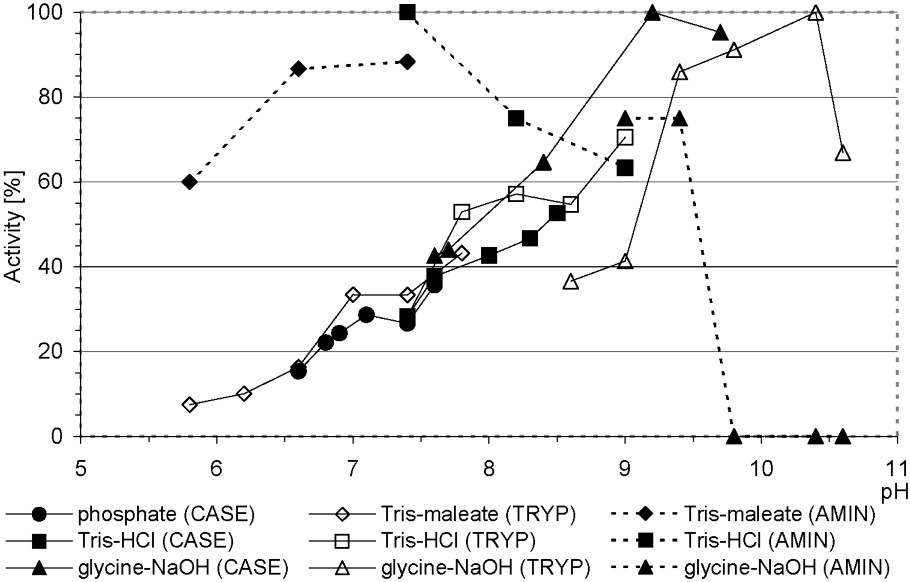

The highest total proteolytic (caseinolytic) activity in relation to various media was stated in glycine–NaOH buffer within a pH range of 9.2–9.6. For trypsin, it was noted in the same buffer at pH 10.4. On the contrary, high midgut aminopeptidase activity occurred in a wide pH range: 6.6–9.4 (Fig. 1). According to Houseman and co-workers, Apollo larvae trypsin is of a ‘high-alkaline’ type (optimal

Total proteolytic (caseinolytic), trypsin, and aminopeptidase activities in midgut of Parnassius apollo larvae in relation to buffers pH. Abbreviations: AMIN, aminopeptidase activity; CASE, caseinolytic activity; TRYP, trypsin activity.

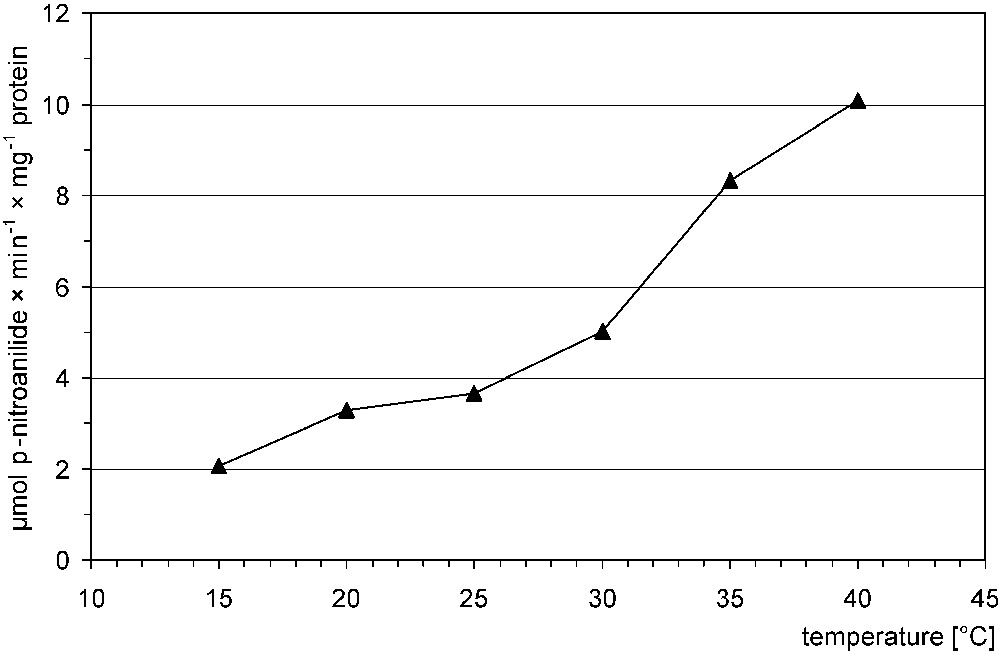

Trypsin activity of P. apollo larvae increased along with the elevation of incubation temperature (Fig. 2). The dependence was not linear – the highest

Trypsin activity of P. apollo larvae in relation to incubation temperature.

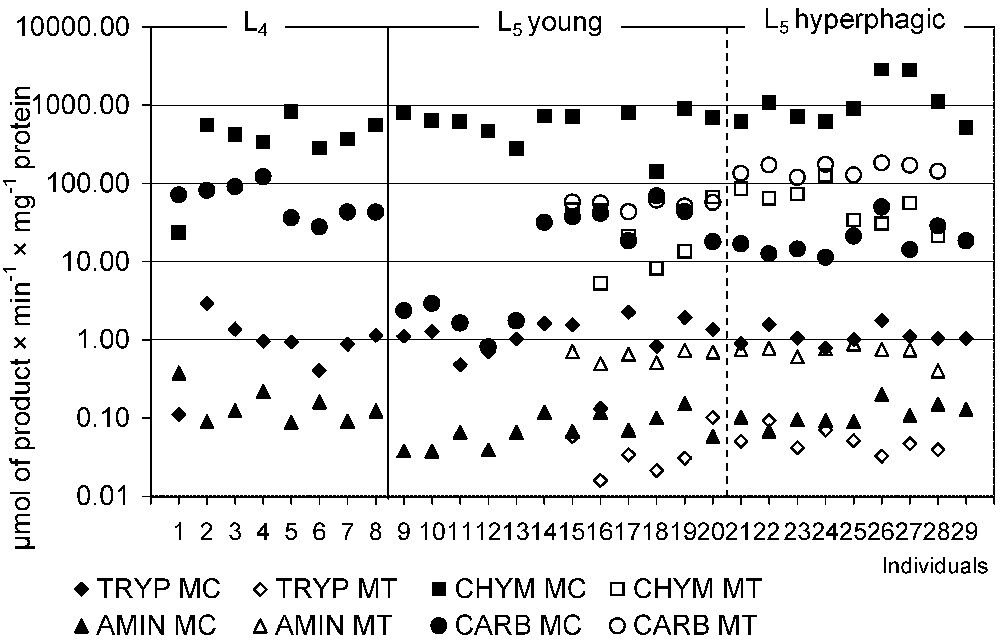

Digestion of polypeptides and oligopeptides was stated in the midguts of L4 and L5 instars of P. apollo larvae (Table 2, Fig. 3). In L5 larvae total proteolytic activity was lower in the MT than in the MC samples (

Protease activities in the midgut of Parnassius apollo larvae (mean±SD)

| Enzyme | L4⁎⁎ | L5 | |

|

|

MC ( |

MC ( |

MT ( |

| Total proteolytic (caseinolytic) activity⁎⁎⁎ | 1551.162 ± 839.893 | 1284.886a ± 479.031 | 220.811a ± 121.090 |

| Trypsin | 1.089 ± 0.838 | 1.167a ± 0.493 | 0.049a ± 0.025 |

| Chymotrypsin1 | 0.037 ± 0.054 | 0.009 ± 0.008 | 0.007 ± 0.001 |

| Chymotrypsin2 | 0.420 ± 0.234 | 0.862a ± 0.725 | 0.046a ± 0.034 |

| Aminopeptidase | 0.159 ± 0.099 | 0.091a ± 0.042 | 0.676a ± 0.132 |

| Carboxypeptidase3 | 64.159 ± 32.221 | 21.738a ± 18.247 | 110.530a ± 53.879 |

| Carboxypeptidase | 22.427 ± 22.305 | 54.182b ± 6.103 | |

| (in ‘young’ subgroups: N=12 and 6) | |||

| Carboxypeptidase | 20.821a ± 12.110 | 152.791ab ± 24.535 | |

| (in ‘hyperphagic’ subgroups: N=9 and 8) |

⁎ For product description see Table 1.

⁎⁎ Due to shortage of L4 specimens, there is lack of data for the enzyme activities in the MT samples.

⁎⁎⁎

Total proteolytic activity is expressed in

1 Assayed with G-F-pNA (N-glutaryl-l-phenylalanine p-nitroanilide).

2 Assayed with Suc-AAPF-pNA (N-succinyl-alanine-alanine-proline-phenylalanine p-nitroanilide).

3 Mean ± SD for ‘young’ and ‘hyperphagic’ subgroups together.

a

Significant differences (

b

Significant differences (

The endo- and exoproteolytic activity in midgut tissues (MT) and liquid midgut contents (MC) in individuals of Parnassius apollo. Abbreviations: AMIN, aminopeptidase activity; CARB, carboxypeptidase activity; CHYM, chymotrypsin activity towards Suc-AAPF-pNA; TRYP, trypsin activity.

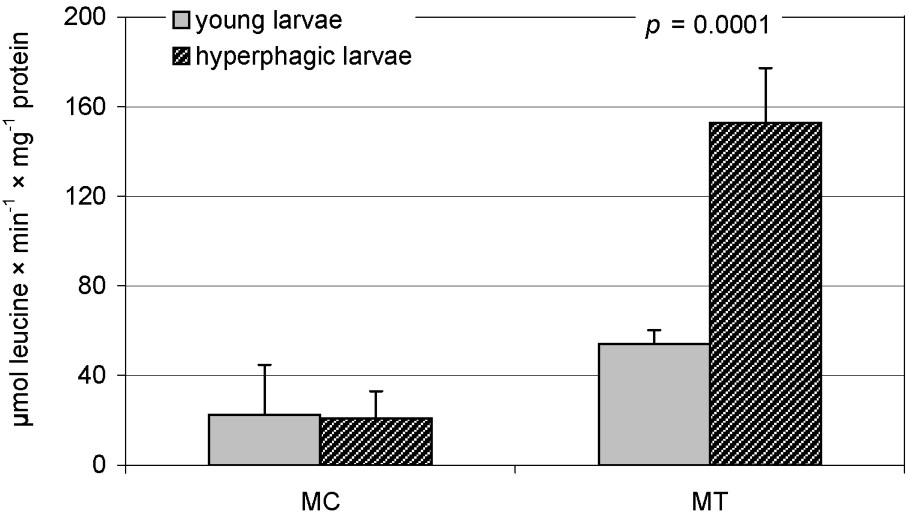

In ‘young’ and ‘hyperphagic’ larvae, activities of the assayed enzymes were similar, except carboxypeptidase, which was higher in the MT samples obtained from ‘hyperphagic’ individuals (Table 2, Fig. 4). However, there was a significant negative correlation between body mass and caseinolytic activity both in the MT and the MC samples (Table 2). Total protein contents in these samples correlated positively, but insignificantly, with body mass in both age groups (data not shown). This indicates then that the relative importance of protein digestion was decreasing as the larvae were growing up. On the other hand, in the same individuals, positive correlations were found between body mass and chymotrypsin activity (towards Suc-AAPF-pNA): significant in the MT and insignificant in the MC. A significant positive correlation with body mass was also found for carboxypeptidase activities in the MT (Table 3). To elucidate whether amino acids could be obtained by Apollo larvae from non-protein, low-molecular-weight compounds, comparisons were made between activities of exopeptidases and those of specific glycosidases. Strong positive correlations in midgut tissue of L5 larvae were found only for carboxypeptidases (Table 3).

Carboxypeptidase activity in midgut tissue (MT) and liquid midgut contents (MC) in ‘young’ and ‘hyperphagic’ L5 Parnassius apollo larvae (‘subgroups’). The value of p (T Tukey's test for unequal sample size) shows a difference in the enzyme activity between the ‘subgroups’.

Significant correlations between assayed protease activities, and between their activities and body mass (bm) or gluco- and galactosidases, in midgut tissues (MT) and liquid midgut contents (MC) of Parnassius apollo L5 larvae

| Midgut compartment | N | Regression equation | r | p | t |

| MT | 14 |

|

0.654 | 0.01 | 3.00 |

| MC | 21 |

|

0.645 | 0.002 | 3.68 |

| MC | 21 |

|

0.606 | 0.004 | 3.32 |

| MC | 21 |

|

0.473 | 0.030 | 2.34 |

| MT | 13 |

|

0.727 | 0.005 | 3.51 |

| MT | 13 |

|

0.717 | 0.006 | 3.41 |

| MT | 13 |

|

−0.686 | 0.01 | −3.12 |

| MC | 20 |

|

−0.548 | 0.01 | −2.78 |

| MT | 14 |

|

0.956 | 7.6×10−8 | 11.53 |

| MT | 14 |

|

0.815 | 4.0×10−4 | 4.88 |

| MT | 14 |

|

0.718 | 0.004 | 3.57 |

| MT | 14 |

|

0.702 | 0.005 | 3.42 |

⁎ Data for gluco- and galactosidases taken from [23].

4 Discussion

Azocasein and casein are widely used as a measure of total proteolytic digestive capacity, hence allowing comparison among different insects. Christeller and co-workers pointed out that casein, as a milk protein, may not be a suitable measure for herbivores but, even in leaf-eating species, it was digested more effectively than rubisco – a major soluble leaf protein. However, they found that caseinolytic activity was relatively low in leaf-eaters, and in oligophagous species it was nearly two times lower than in polyphagous ones [15,19]. Using the same assay procedure, we have stated that caseinolytic activity of Apollo larvae was much higher than in a leaf-eating chrysomelid beetle (Chrysolina sp.: Coleoptera), leaf-mining lepidopteran larvae (Cameraria ohridella: Lepidoptera), grasshopper larvae and adults (Stenocepa sp.: Orthoptera), and omnivorous house cricket adults (Acheta domesticus: Orthoptera) (unpublished data).

The optimal pH conditions for assayed proteolytic enzymes in P. apollo midgut samples were similar to those found in other lepidopteran species [15]. Endopeptidases hydrolyzed effectively in alkaline environment, while aminopeptidases operated in a broad pH range. The pH profile of caseinolytic activity resembled that of trypsin. Similar results, obtained for Ostrinia nubilalis (Pyralidae) larvae, led Houseman and co-workers to the suggestion that trypsin is the major protease in that species [36]. We have stated a strong positive correlation between trypsin and caseinolytic activity in midgut contents (

Previous studies on insects' endoproteases assumed their similarities to mammalian enzymes, and numerous data on protein digestion in insects was gathered by methods applied for studies on mammals. Optimal pH allowed a classification of trypsins into high (>10.0) and low (∼9.0) alkaline [36]. The highest activity of Apollo larvae trypsin stated in glycine–NaOH buffer (pH 10.4) indicates that this endoprotease belongs to a high-alkaline type.

Lee and Anstee [17] noticed that concentrations of DMF (N,N-dimethylformamide) in the assay mixture higher than 7.7% v/v decreased trypsin activity. We used the substrate from the same supplier (SIGMA) but, to obtain the same final concentration of B-R-pNA, we had to use 15% v/v DMF (see also Baker [28]). We cannot estimate whether any inhibition of trypsin activity resulted from the applied concentration of DMF. Nevertheless, it is clear from the available data that at least trypsin amidase activity in P. apollo larvae falls into the lower range of the activities stated for other leaf-eating Lepidoptera [15,18,19]. This data strengthens our suggestion that trypsin plays a minor role in protein digestion in this species.

An increase in endoprotease activity, in midgut of lepidopteran larvae, along with the increase of incubation temperature, with a maximum at around 50 °C, has been documented in various species (e.g., [17,20,37]). A discontinuity (‘break point’) at approximately 30 °C in the Arrhenius plots of endoprotease activities was found [17]. Our data did not enable us to make such a plot for comparison; however,

The use of G-F-pNA (N-glutaryl-l-phenylalanine p-nitroanilide) – substrate for vertebrate chymotrypsin, once commonly used for detection of the enzyme also in arthropods, revealed negligibly low activity both in the MT and the MC of the Apollo midgut. Tsai and co-workers [38] have shown that chymotrypsin in some arthropods has an extended binding site that requires a longer peptide substrate (up to five amino acid residues instead of two). Lee and Anstee confirmed this observation in Spodoptera littoralis (Noctuidae) larvae [17]. Recently, this finding was generalized for insects [34]. Higher chymotrypsin activity towards Suc-AAPF-pNA (than towards G-F-pNA) suggests that P. apollo also has this type of enzyme. The ratio of trypsin to chymotrypsin activity (towards B-R-pNA and Suc-AAPF-pNA, respectively), as shown by a regression analysis (Table 3), resembled that stated in other oligophagous species [15].

Relatively low activities of endoproteases in midgut of P. apollo larvae suggest that plant proteins are poorly utilized. Mandibles of the last-instar larvae cut relatively large bites of the leaves. Negligible activity of cellulase [23] enables access of digestive enzymes only to the content of mechanically destroyed cells and to the nutrients leaking through pores of the cell wall (symplast transport) [39]. Virtually all the chloroplast proteins (including rubisco) of the intact cells are unavailable for the larvae. Hence, fast passage of the chyme through the gut of Apollo larvae, enabling increased consumption, may be a compensatory mechanism, which allows obtaining sufficient amounts of nutrients and energy from available sources. In consequence, in leaf-eating insects with grazing mouth-parts, a decrease in mechanical digestion efficiency in subsequent larval instars may be expected. If this is not compensated by enhanced enzymatic digestion, decreased assimilation efficiency (assimilation to consumption ratio) should be observed. In fact, this was documented for numerous insect species, belonging to various taxa [40]. We have made similar observation in the last-instar P. apollo larvae when compared to the previous one (L4) [41]. On the other hand, late-instar larvae of sap-feeders (Hemiptera) have increased assimilation efficiency in comparison with the young ones [40].

Limited availability of the leaf proteins points out that the feeding larva must obtain exogenous amino acids from protoplast either directly or from oligopeptides. These molecules easily pass through the peritrophic membrane into the exoperitrophic space; hence their digestion occurs mainly in the midgut wall (MT samples). Some molecules of aminopeptidases and carboxypeptidases are released into midgut lumen, since their activities were detected also in the MC samples. This has already been shown for aminopeptidases in Lymantria dispar (Lymantridae) and Heliothis zea (Noctuidae) [18,42]. On the other hand, carboxypeptidase activity in H. zea and Erinnyis ello (Sphingidae) was not found in the midgut tissue [42,43]. A question remains whether the molecules of the enzyme operate in the fluid layer adjacent to the epithelium or may also diffuse into the endoperitrophic space. Aminopeptidase in Apollo midgut was similar to that stated in the gut of some other leaf-eating lepidopterans, in respect of both pH range (6.0–9.0 in S. littoralis [16] and 7.5–10.0 in H. zea [42]) and level of specific activity [18,42].

Carboxypeptidase A activity in Apollo larvae was very high in comparison with aminopeptidase activities. In comparative studies on larvae of 12 lepidopteran pest species, Christeller and co-workers found 10-fold higher carboxypeptidase activity in leaf-eaters than in flower-, fruit- and seed-eaters [19]. High activity of the enzyme in Apollo larvae fits well these findings. Hence, we conclude that in scarcity of available proteins, Apollo larvae probably use low-molecular-weight compounds, e.g., glycoproteins, to obtain amino acids. Our findings that in midgut tissue (but not in the gut contents), the enzyme activity was significantly correlated with activities of glucosidases and galactosidases, support this conclusion (Table 3). Supposed liberation of various aglycone parts with potentially adverse effects on larval metabolism is consistent with observation of limited larval feeding on a single food-plant [8]. It is then plausible that some chemical defence is induced in the Apollo larvae food-plant in response to feeding.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Polish State Committee for Scientific Research (Project No. 6 P04F 085 21). We express our thanks to Managing Director and Scientific Board of The Pieniny National Park for administrative support and Mr Tadeusz Oleś for his expertise and help in Apollo breeding.