1. Introduction

Codon-amino acid assignments according to the genetic code are not random [1] because many codon and anticodon properties correlate with properties of cognate amino acids [2, 3, 4]. Numerous analyses indicate the genetic code minimizes error impacts for various processes and properties: mutations on protein structure [5, 6], how proteins fold [7, 8, 9], tRNA misloading by tRNA synthetases [10, 11, 12, 13], frameshifts during translation before and after these occur (before occurrence [14, 15, 16, 17], after occurrence [18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]). The genetic code maximizes the diversity of physicochemical properties of coded amino acids [24, 25] and optimizes error according to several properties at the same time [1].

1.1. Genetic code evolution

Numerous hypotheses on inclusion orders of amino acids in the genetic code have been deducted from different properties and experiments. These hypotheses predict orders by which amino acids were assigned to codon(s) [26, 27]. Most of these unrelated hypotheses predict congruent orders, justifying a consensual order of amino acid inclusion in the genetic code [26, 27]. Ulterior analyses produced genetic code inclusion orders that converge with these amino acid inclusion ranks. The average position of amino acid types in modern proteins correlates with these inclusion ranks. The mean position of ancient amino acids is closer to the protein C-terminus, recently included amino acids are on average closer to the protein N-terminus, which corresponds to the gene’s 5’ extremity with the initiation/start codon [28].

1.2. Stereochemical genetic code codon-amino acid assignments

This shows that structures of modern biomolecules embed fossilized information on the origins of life. Indeed, ribosome X-ray crystal structures show that contacts between ribosomal RNA nucleotide triplets and ribosomal protein residues favor amino acid-codon/anticodon assignments. Amino acids that integrated early the genetic code favor contacts with their codons, late amino acids favor contacts with their anticodons [29]. This shows two different steps during the formation of the genetic code: (1) an adaptor/tRNA-free translation where codons interacted directly with amino acids, and (2) tRNA-based translation. Both results confirm, at the level of ribosomal structure, the hypothesis that (at least some of) the genetic code’s assignments result from nucleotide-amino acid affinities due to stereochemical interactions.

The importance of stereochemical interactions is not surprising, as these also determined homochirality of life’s major molecules, right-handed RNA (R-RNA) and left-handed amino acids (L-amino acids), which interact better when these have opposite handedness [30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. The first step in genetic code evolution deduced from ribosomal crystal structures suggests direct codon-amino acid stereochemical interactions. This is in line with observations that in most mRNAs, nucleotide affinities for amino acids correlate with amino acid polar requirements [35, 36, 37]. These observations imply that frequencies of observed contacts between nucleotides and amino acids, from which nucleotide-amino acid affinities are deduced, are approximated by the amino acid hydrophobicity, as these interactions are broadly spoken hydrophobic interactions. This implies that genetic code assignments resulted from stereochemical interactions before proto-tRNAs switched from their function as initiators of RNA/DNA polymerizations [38, 39] to their main modern function in translation. Translations by direct codon-amino acid interactions are in line with a primordial peptide-RNA world, rather than a primordial RNA world [40].

1.3. Theoretical minimal RNA rings as models for the primitive RNA world

Here we study associations between codon affinities for their cognate amino acid and that amino acid’s hydrophobicity, specifically in the context of 25 theoretical minimal RNA rings [41, 42, 43, 44, 45]. These 22-nucleotide long RNAs were designed to code for a start and a stop codon and once for each of the genetic code’s 20 amino acids by three consecutive translation rounds (Figure 1). This ensures maximal coding capacity over the shortest possible length. Their design was also constrained to form a stem-loop hairpin. Independent secondary structure analyses confirmed most theoretical minimal RNA rings resemble proto-tRNAs [44, 45]. A cognate amino acid, in the sense of tRNA acylation, can be assigned to each RNA ring, based on their predicted anticodon sequence [46]. Theoretical RNA rings also fit predictions that circular RNAs had critical roles in the early formation of protogenomes [47]. Most importantly, their design assumes the genetic code’s pre-existence to tRNA-assisted translation. It is of note that some RNA ring secondary structures resemble more rRNAs than tRNAs [46], and that maturation of some modern tRNAs includes circularization [48].

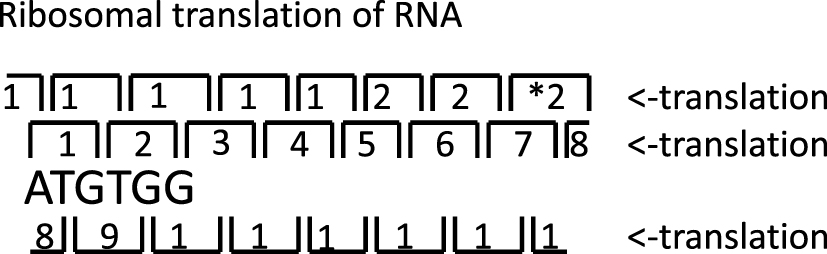

Translation in three rounds of theoretical minimal RNA ring. Numbers indicate codon order. * indicates stop codon.

The design of theoretical minimal RNA rings minimizes sequence length and maximizes the diversity of coded amino acids. Circularized tRNAs are intermediates in post-transcriptional modifications of some tRNAs [40]. Circular RNAs regulate gene expression in modern cells [51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57] and are occasionally translated [58]. They code for proteins with different functions, frequently in muscles of mammals [59]. The assumption of overlap coding is also realistic: artificially designed genes coding over three overlapping frames for three predefined proteins from different protein domains are relatively easy to produce [60]. This fits with observations suggesting that overlap coding is a common property of genes [61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69]. Indeed, the genetic code is optimized for coding after frameshifts [1, 67, 68, 69].

We expect that associations between RNA ring codon affinities with cognate amino acid hydrophobicity in the peptides coded by the RNA rings resemble those observed in natural modern genes. Two evolutionary scenarios exist in this context. (1) This association appeared spontaneously and, in modern genes, is a carryover from an earlier translation mechanism lacking tRNA and ribosome. In this case its strength should decrease with the genetic code inclusion order of cognate amino acids of RNA rings. (2) This association results from an evolutionary process and reflects processes that still occur in modern cells. According to this scenario, the strength of this association should increase from early to late RNA rings.

2. Materials and methods

We translated the 25 peptides coded by the theoretical minimal RNA rings (Table 1) according to the standard genetic code and estimated the strength of associations between their codon-amino acid affinity and the hydrophobicity of their cognate amino acids forming the peptide. Codon-amino acid affinity is calculated by summing the affinity of single nucleotides forming the codon with the amino acid coded by the codon [35]. These single nucleotide affinities for amino acids are estimated from nucleotide-amino acid contact frequencies in crystal structures of interacting RNA-protein complexes [35].

Minimal RNA rings and corresponding peptide sequences according to regular translations. In column 1, r indicates secondary structures resembling more rRNAs, remaining are more tRNA-like, capitals indicate the presumed cognate amino acid of the RNA ring if considered as a proto-tRNA according to its predicted anticodon. * indicates stop codons. Columns 4 and 5 indicate Pearson correlation coefficients r ×100 between codon-amino acid affinity [35] and amino acid hydrophobicity estimated from distribution equilibria between vapor and aqueous solution (R1, log (RHvap/RHwater), R2, hydration potential, [73])

| RNA | AA | CDs | Peptide | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | AATTCATGCCAGACTGGTATGA | NSCQTGMKFMPDWYEIHARLV* | −13.0 | −13.7 |

| 2 | M | CATGCCAGAAATTCTGGTATGA | HARNSGMTCQKFWYDMPEILV* | −10.7 | −11.8 |

| 3 | S | ATGGTGCCACTATTCAAGATGA | MVPLFKMNGATIQDEWCHYSR* | −20.9 | −15.0 |

| 4 | Pyl | ATGCTATTCACCAAGATGGTGA | MLFTKMVNAIHQDGECYSPRW* | −13.4 | −8.3 |

| 5 | V | ATGGTGCTACCATTCAAGATGA | MVLPFKMNGATIQDEWCYHSR* | −16.8 | −9.7 |

| 6 | N | ATGGCCTATTCACAAGATGTGA | MAYSQDVNGLFTRCEWPIHKM* | −19.1 | −16.8 |

| 7 | D | ATGCCACTGGTATTCAAGATGA | MPLVFKMNATGIQDECHWYSR* | −19.8 | −14.1 |

| 8 | R | ATGTGGCCTACATTCAAGATGA | MWPTFKMNVAYIQDECGLHSR* | −22.6 | −18.6 |

| 9 | Sec | ATGCCAAGATGGTATTCACTGA | MPRWYSLNAKMVFTECQDGIH* | −19.8 | −14.1 |

| 10 | L | GCAATGTTTATGGAGACCATAA | AMFMETISNVYGDHKQCLWRP* | −25.8 | −19.8 |

| 11 | P | TATGTTTGGAGACCAAGCATAA | YVWRPSMICLETKHNMFGDQA* | −24.4 | −18.9 |

| 12 | E | TTCATGCCAGAAACTGGTATGA | FMPETGMIHARNWYDSCQKLV* | −24.7 | −19.7 |

| 13 | G | ATGGTACTGCCATTCAAGATGA | MVLPFKMNGTAIQDEWYCHSR* | −23.6 | −16.0 |

| 14 | I | GCAGAATGTTTATGGACCATAA | AECLWTISRMFMDHKQNVYGP* | −29.0 | −24.2 |

| 15 | Q | AATATGTTTGGACCAAGCATAG | NMFGPSIEYVWTKHRICLDQA* | −35.7 | −34.5 |

| 16 | L | TATGTTTGGAAGCCAGACATAA | YVWKPDIICLEARHNMFGSQT* | −20.8 | −22.7 |

| 17 | K | TACATTTGGAAGCCAGATGTAA | YIWKPDVMHLEARCNTFGSQM* | −27.1 | −27.0 |

| 18 | S | ACAATGTTTATGGAAGCCATAG | TMFMEAIDNVYGSHRQCLWKP* | −32.9 | −37.8 |

| 19 | A | ATGGAAGCCATTTACAATGTAG | MEAIYNVDGSHLQCRWKPFTM* | −38.4 | −38.3 |

| 20 | W | TACAGATGGAAGCCATTTGTAA | YRWKPFVMQMEAICNTDGSHL* | −27.1 | −27.0 |

| 21 | C | AACATGCCAGATTCTGGTATGA | NMPDSGMKHARFWYETCQILV* | −24.8 | −17.7 |

| 22 | H | TGCCAGAAACATTCTGGTATGA | CQKHSGMMPETFWYDARNILV* | −21.8 | −17.7 |

| 23 | T | TATGGTTCTGCAAGAACCATGA | YGSARTMIWFCKNHDMVLQEP* | −28.2 | −17.2 |

| 24 | Y | TACCATTCTGCAAGAATGGTGA | YHSARMVMPFCKNGDTILQEW* | −21.7 | −13.5 |

| 25 | G | ATGGTGCCATTCAAGACTATGA | MVPFKTMNGAIQDYEWCHSRL* | −19.9 | −14.5 |

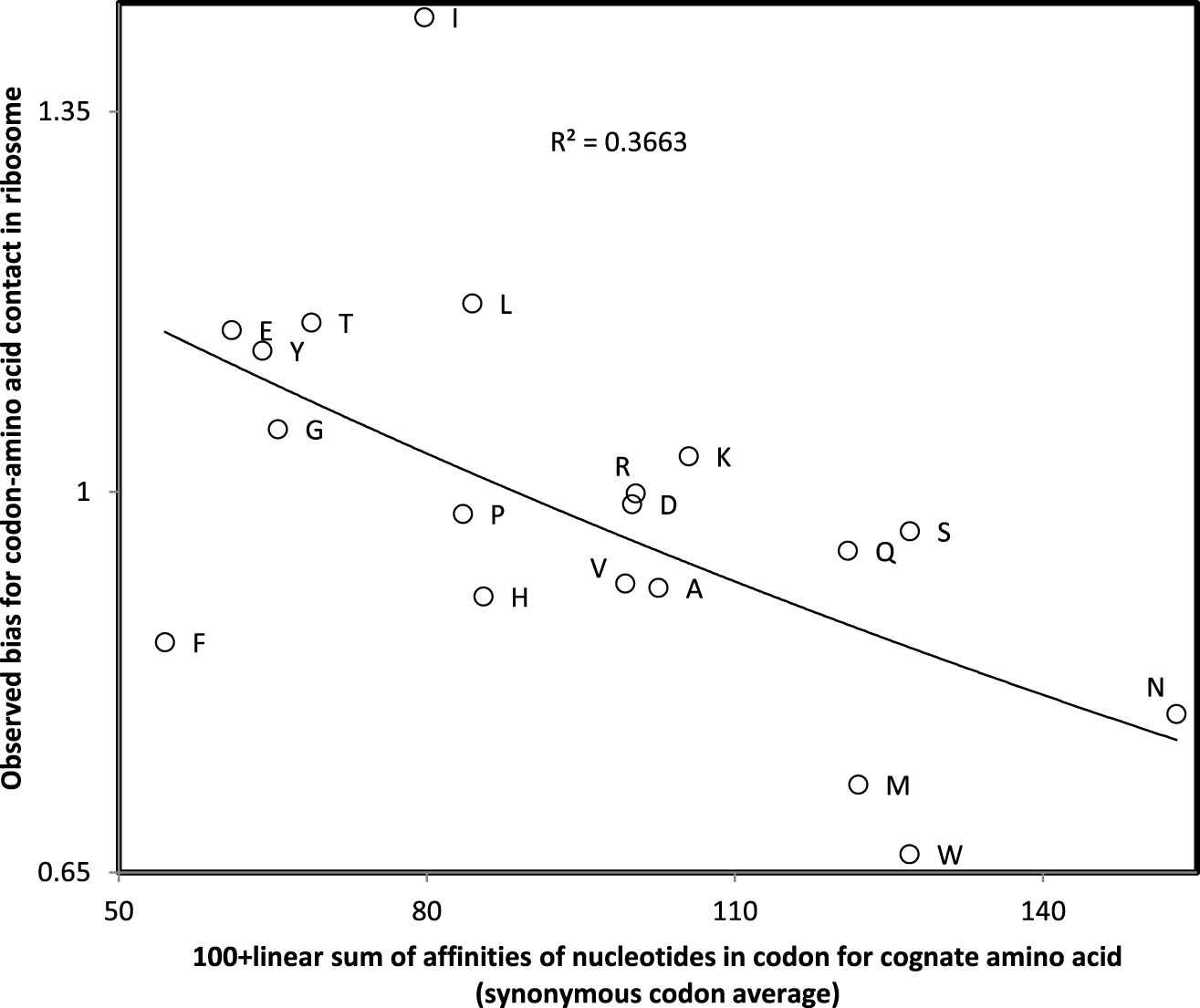

These linear sums of affinities of single nucleotides with amino acids produce the same trinucleotide affinity for trinucleotides N1N2N3, N1N3N2, N2N1N3, N2N3N1, N3N1N2 and N3N2N1, though in most cases, these permutations do not code for the same amino acid. Hence this sum of single nucleotide affinities must be considered as an approximation of trinucleotide-amino acid affinities. Nevertheless, biases for codon-amino acid contacts observed in ribosomal crystal structures [29] correlate with these codon affinities calculated by summing single nucleotide affinities (Figure 2). This preliminary observation justifies the linear sum of single nucleotide affinities to approximate codon-amino acid affinities.

Pearson correlation coefficients r between codon affinity and cognate amino acid hydrophobicity (as for Table 1, [73], Log is for log (RHvap/RHwater) and Pot for the hydration potential used as hydrophobicity estimates) for each of the 21 amino acid-coding codons in the 25 theoretical minimal RNA rings from Table 1. Analyses are across the 25 RNA rings, keeping constant the codon position. Asterisks show P < 0.05. P values are two tailed

| Position | Log | Pot |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | ||

| 1 | 0.100* | 0.101* |

| 2 | −0.070* | −0.002* |

| 3 | −0.292* | −0.231* |

| 4 | −0.290* | −0.265* |

| 5 | −0.508* | −0.331* |

| 6 | −0.618* | −0.602* |

| 7 | −0.697* | −0.697* |

| Round 2 | ||

| 8 | −0.535* | −0.612* |

| 9 | −0.333* | −0.321* |

| 10 | −0.074* | −0.043* |

| 11 | 0.006* | −0.067* |

| 12 | −0.607* | −0.544* |

| 13 | −0.599* | −0.137* |

| 14 | −0.063* | −0.260* |

| Round 3 | ||

| 15 | −0.775* | −0.459* |

| 16 | −0.116* | −0.116* |

| 17 | −0.055* | −0.047* |

| 18 | −0.375* | −0.333* |

| 19 | −0.380* | −0.433* |

| 20 | −0.028* | −0.019* |

| 21 | −0.210* | −0.199* |

| 22-stop | n.d. | n.d. |

Pearson correlation coefficients r were calculated between codon affinities and several estimates of amino acid polar requirements, experimental and calculated polar requirements [70, 71, 72], two estimates of proportions of accessible versus buried amino acid surfaces in proteins [71, 72], and several estimates of affinities of side chains of amino acids for solvent water [73, 74], other solvents [75, 76] and for water at different temperatures (at 25 °C versus 100 °C [78]).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Codon affinity-amino acid hydrophobicity correlations at specific codons

Our first analysis considers each codon across the 25 theoretical minimal RNA rings and calculates the correlation between codon affinity and hydrophobicity for the amino acid coded by each codon. This produces 21 Pearson correlation coefficients r for each estimate of hydrophobicity, for all 21 codon positions coding for an amino acid, and aligned as shown in Table 2. These correlations are expected to reflect those observed for regular mRNAs and their cognate proteins. Affinities are estimated from nucleotide-residue contact frequencies and log-transformed to correspond to contact enthalpies. If affinities are proportional to amino acid hydrophobicities as observed in regular genes, correlations with log-transformed estimates of affinities should produce negative correlations with amino acid hydrophobicities.

Among seventeen different hydrophobicity scales tested, the highest number of positions for which negative associations between codon affinity and amino acid hydrophobicity is 20 among 21 positions, for the scales based on the distribution of equilibria between the dilute aqueous solution and the vapor phase at room temperature (log (RHvap/RHwater), hydration potential [74]). Note that Pro is absent from these scales. Hence the pattern observed in regular mRNAs and proteins (negative correlations) is also observed for most positions in theoretical RNA rings according to these hydrophobicity scales. This majority is statistically significant (P = 0.00001, two tailed sign test) and remains so also after considering test multiplicity, even according to Bonferroni’s overconservative correction (P = 0.05∕17 = 0.002941, which is still higher than P = 0.00001). The overall tendency is weaker when considering other hydrophobicity scales, notably those obtained according to similar equilibria between solvents, but other than water, the natural solvent of biological systems. These are not reported in the following as results were systematically strongest for the scales presented in [74].

This analysis also produces statistically significant correlations at specific codons in RNA rings. All six statistically significant correlations are negative as expected from modern mRNAs and proteins and are located at the transition between each translation round, for amino acids coded by the 6th, 7th, 8th, 12th, 15th, and 19th codons in RNA rings. This would suggest that peptides interact with their template RNA ring at each new translation round. This pattern emerging from theoretical RNA rings is not part of their design, and might reflect properties of RNA-templated, pre-tRNA translation.

Observed bias for contacts between codon and cognate amino acid in the ribosome crystal structure (Johnson and Lee 2010) as a function of linear sum of single nucleotide affinities for cognate amino acid averaged across all synonymous codons (strong affinities correspond to low values on the x-axis). The correlation (r = −0.605, one tailed P = 0.003) justifies the use of the sums of single nucleotide affinities to approximate codon affinities.

Correlations obtained for hydrophobicity scales estimated from distribution equilibria between neutral solution and cyclohexane at 25 °C and 100 °C [77] produce less clear patterns. Patterns are slightly stronger at 100 °C than 25 °C, putatively suggesting that the codon-amino acid associations we observe in modern organisms evolved originally at high temperatures, in line with some previous considerations on origins of life and the genetic code [78, 79, 80, 81, 82].

3.2. Codon affinity-amino acid hydrophobicity correlations for specific RNA rings

Our second analysis tests for correlations between codon affinity and amino acid hydrophobicity (distribution equilibria between the dilute aqueous solution and the vapor phase at room temperature [74]) across codons, for each specific RNA ring (Table 1). All 25 correlations are negative (P < 0.05 for RNA ring 19), a statistically significant majority of cases (P = 0.00000003, two tailed sign test). This means that the association between codon affinity and amino acid hydrophobicity for the 25 RNA rings resembles that observed in modern genes.

3.3. Evolution of associations between codon affinity and amino acid hydrophobicity

Each of the 25 theoretical minimal RNA rings, because of their similarity with consensus tRNA sequences, can be assigned to a cognate amino acid according to their predicted anticodon sequence, assuming a tRNA-like function. Each of these tRNA-cognate amino acids is assigned a rank of inclusion in the genetic code, according to various hypotheses on genetic code inclusion history. Interestingly, and despite that these numerous hypotheses have very different backgrounds, from mathematical (e.g. the natural circular code, [14], the algebraic model [84]), physicochemical (e.g. amino acid yields in experiments mimicking early earth condition [85], amino acid size-complexity [86]) to physiological (e.g. the metabolic coevolution hypothesis [87], the self-referential model [88]), they tend to predict overall congruent histories of genetic code assignments of amino acids (40 hypothetical inclusion orders reviewed in [26, 27]). Some hypotheses are derived from aminoacylating rules of small RNA helices [89, 90] and tRNAs [91], affecting protein folding [9, 92], enabling to define a primordial code in tRNA acceptor stems and an associated order of integration of amino acids in the genetic code.

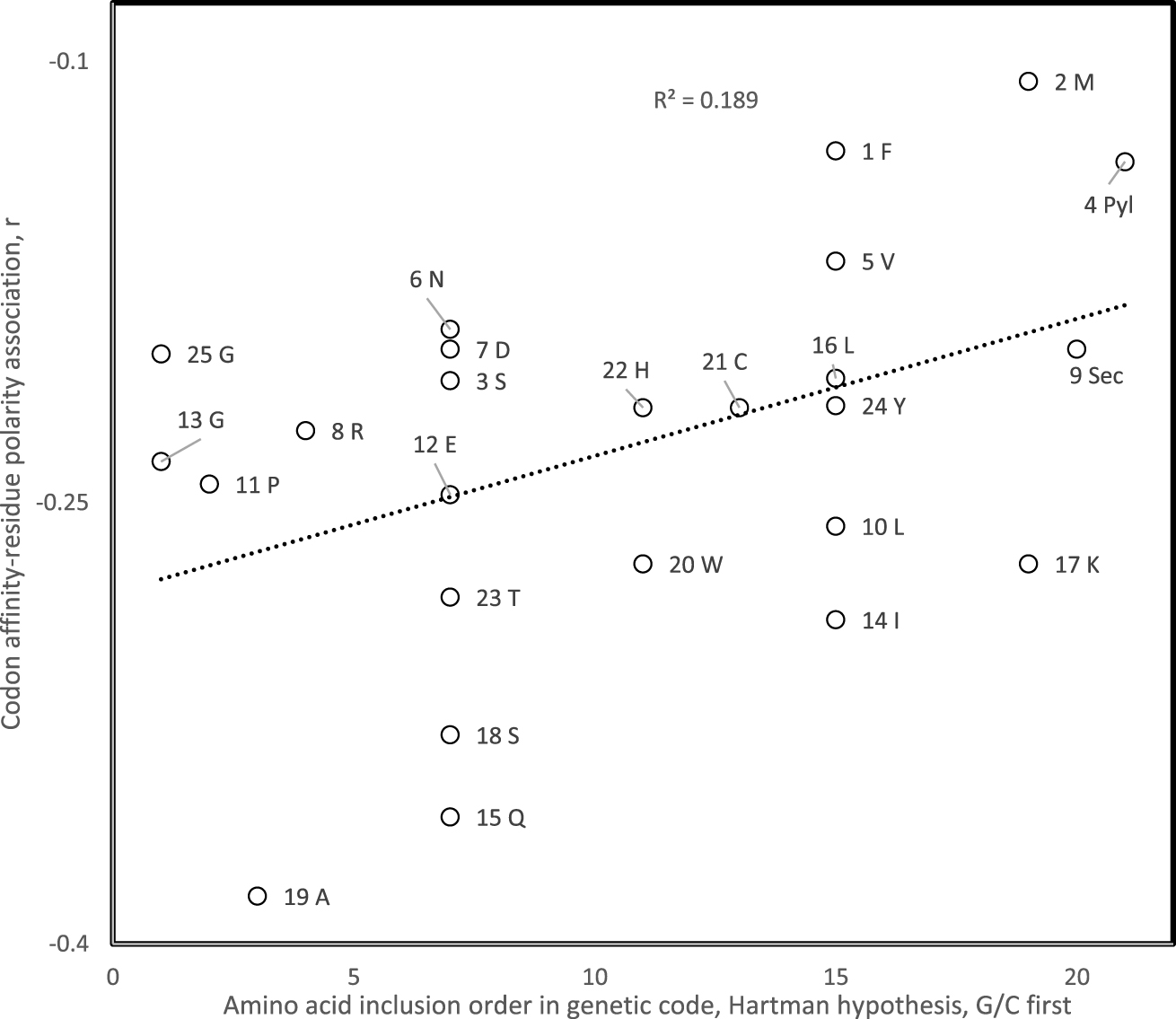

The inclusion ranks of the RNA ring predicted cognate amino acids are assumed to reflect the history of the theoretical organic system based on these 25 theoretical RNA rings and their cognate peptides (cognate here is used in the sense of the peptide translated from the RNA ring as an ancient template for protein synthesis). We examined the associations of the Pearson correlation coefficients between codon affinity and amino acid hydrophobicity for the 25 RNA rings and the inclusion ranks of their cognate amino acid (cognate is used here in the sense of the amino acid presumably aminoacylated to the RNA ring in relation to its presumed tRNA-like function). The RNA rings with predicted anticodons matching cognate amino acids selenocysteine and pyrrolysine were assigned penultimate and last genetic code inclusion ranks.

Scenario 1 assumes that correlations between codon affinity and amino acid hydrophobicity reflect spontaneous associations that were the physicochemical basis for tRNA- and ribosome-free translation pre-existing modern translation. Along that scenario, codon affinity-amino acid hydrophobicity associations observed today would be remnants of this earlier translation mechanism. Hence Pearson correlation coefficients r between codon affinity and amino acid hydrophobicity of RNA rings are expected to increase (become more positive) with the inclusion rank of the amino acid assigned as proto-tRNA cognate for that RNA ring.

Pearson correlation coefficient of association between amino acid polar requirement and codon affinity for that amino acid for 25 theoretical minimal RNA rings of 22 nucleotides coding after three translation rounds for a start and stop codon and one codon per amino acid, as a function of the genetic code inclusion order of the presumed cognate amino acid of that RNA ring if considered as a proto-tRNA. The tRNA cognate amino acid is determined by the nucleotide triplet at the predicted anticodon position. The genetic code inclusion order is according to Hartman’s primordial one nucleotide code, assuming G and C were first [93, 94, 95, 96, 97].

Scenario 2 expects that correlations evolved towards becoming more similar to what is known for extant genes and proteins, which is generally a negative correlation. Hence Pearson correlation coefficients r between codon affinity and amino acid hydrophobicity of RNA rings are expected to decrease (become more negative) with the inclusion rank of the amino acid assigned as proto-tRNA cognate for that RNA ring.

Correlation coefficients r obtained for associations between codon affinities and hydrophobicity estimated from distribution equilibria between vapor and aqueous solution fit scenario 1 for 38 among 40 hypotheses for genetic code evolution of amino acid inclusion orders, a significant majority (P = 8 × 10−8, two tailed sign test). The correlation with amino acid inclusion order is statistically significant at P < 0.05 for eight specific hypotheses for amino acid inclusion orders. The strongest positive association between the presumed inclusion order of the cognate amino acid of the RNA ring and the codon affinity-hydrophobicity correlation r is for Hartman’s hypothesis that assumes that the genetic code started as a one-letter code, then became a two- and then three-letter code, with G and C as primordial nucleotides (r = −0.43, one tailed P = 0.008, Figure 3) [93, 94, 95, 96]. Hence results are in line with scenario 1 that assumes that codon-amino acid hydrophobicity associations in modern gene-protein pairs are remnants of an ancient tRNA- and ribosome-free translation mechanism based on these physicochemical interactions [98], which de facto would have produced the genetic code codon-amino acid assignments [99].

4. Conclusions

Results of analyses of peptides coded by RNA rings and RNA ring codons indicate that codon-amino acid affinity-amino acid hydrophobicity associations were strongest/most negative for RNA rings assumed most ancient. Accordingly, such associations observed in modern genes and their proteins would be remnants of a more ancient translation mechanism lacking tRNAs and ribosome, based on direct physicochemical interactions between codon and amino acid. Codon-amino acid assignments in the genetic code would have resulted from these direct codon-amino acid interactions [99, 100], which would also explain biases for codon-amino acid contacts in the ribosome ([29], and herein Figure 2).

It is unclear how the design of theoretical minimal RNA rings implies complex evolutionary properties such as associations between codon affinity and cognate amino acid hydrophobicity. However, this system actually mimicks unexpectedly numerous and complex properties of the genetic code [99, 101], tRNAs [43], protein coding genes [102, 103], their proteins [104] and of replication origins [105]. This RNA ring system enables to recover probable evolutionary scenarios of tRNAs and rRNAs [104, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111], and the assignment of AUG as universal initiation codon [112]. The design of RNA rings implies that the genetic code pre-existed the emergence of RNA rings. Hence because RNA rings resemble proto-tRNAs, the genetic code had to exist before tRNAs and proto-tRNAs. The association of codon affinity with hydrophobicity for RNA rings indicates that translation according to the genetic code pre-existed tRNA-mediated translation, potentially along a different codon structure where nucleotides at 1st and 2nd codon positions were switched [113, 114], but also evolved towards the situation observed in modern genes during the evolution of this RNA ring-based primordial RNA system [49, 50, 83]. Theoretical minimal RNA rings are realistic models for the RNA world during the transition from translation based on codon affinity for amino acids and lacking tRNA-like adaptors to tRNA-like mediated translation.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Charles W. Jr Carter for his important advice on hydrophobicity estimates.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0