1 Introduction

The development of synthetic strategies to obtain nanocrystals has progressed impressively in the last decade. This level of activity is fuelled by the observation of physical properties, different from those of both isolated atoms and bulk materials, which may vary widely with the size and shape of nanocrystals. Due to increasing needs in miniaturization, nanocrystals may find applications in domains such as electronics or high density recording storage. For both potential applications and fundamental studies, an important challenge of modern materials research is the synthesis of perfect nano-objects (for instance nanowires without structural defects or grain-boundaries), monodispersed in size and shape and replicable in unlimited quantities.

Nanocasting is one of the methods that can be used to obtain nanowires. In this case, the nanowires are formed in the confined space of a host material. The host can be soft, for instance micelles formed by the self assembly of diblock copolymers [1] or hard, for instance anodic alumina membranes [2], single-wall carbon nanotubes [3], crystalline microporous solids and/or mesoporous solids. Among the variety of potential hard hosts, mesoporous silicas, grown by supramolecular templating [4,5], have several advantages: (i) their uniform mesopore dimensions that can be adjusted, at the Å scale, from 20 up to 300 Å; (ii) several channel structures (ranging from layers to 3D) are available; (iii) several morphologies, including powders, films or monoliths, can be prepared; (iv) the silica surface within the pores can be functionalized to obtain charges, acidic or basic properties in order to help the stabilization of metallic precursors; (v) after crystallization of the occluded nanowires, the silica template can be removed by acidic or basic chemical treatments. New classes of materials, potentially interesting as sensors or catalysts because of their size and relative surface to bulk ratio, can then be obtained. The present contribution is devoted to the nanocasting of oxides nanowires in mesoporous silicas, which has surprisingly been much less studied than the nanocasting of metallic nanowires [2,3] and carbons [6].

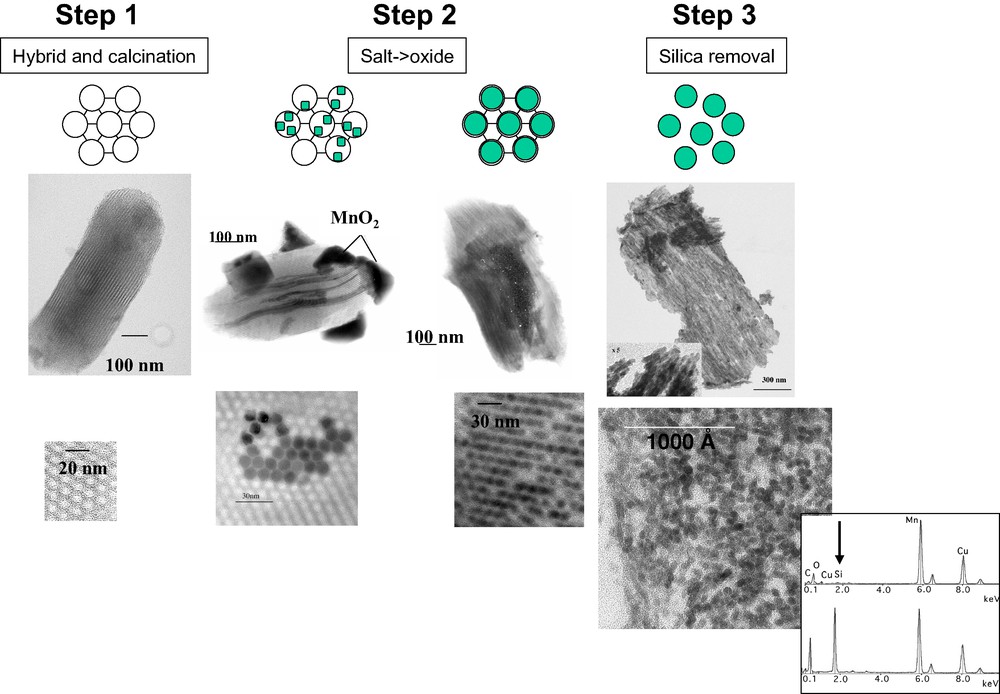

In a typical nanocasting procedure, oxide nanocrystals are formed as negative replicas of the pores of a silica template. The overall procedure requires several independent steps, as schematized in Fig. 1. In step 1, a hybrid material in which aggregates of amphiphilic organic entities are surrounded by silica walls is prepared. The walls are formed by polymerization, starting from a silicon source such as tetraethyl orthosilicate. Well established techniques, involving acidic aqueous solutions and triblock copolymers templates, are used [5]. Complete removal of organic entities either by calcination or by microwave digestion is then necessary. During step 2, guest precursors are introduced within the porosity. The silica can be either previously modified by a chemical treatment, aminosilylation for instance [7,8] or used without modification [9–18]. In the last case, oxides precursors can be introduced in the solid state [9] or using solutions [10–17]. Super-critical fluid introduction have also been tested [18]. A heating treatment (generally a simple calcination, in air) is then used to induce the precursor transformation into oxides. To illustrate this step 2, two sets of independent TEM images are presented in Fig. 1. The images on the left show heterogeneous samples, on which oxide particles are observed both inside and outside silica grains. The images on the right show more homogeneous samples, in which nearly all the mesopores are filled with oxide nanowires. During step 3, the silica walls are etched out by acidic (HF) or basic (NaOH, 2 or 3 M) treatments to liberate the oxide particles.

The nanocasting procedure used to pattern oxide nanoparticles in ordered mesoporous silicas, illustrated by TEM images (lower part, images obtained on ultrathin sections, less than 70 Å thick):

- hybrid materials and their calcined derivatives (step 1): calcined SBA-B silica grains;

- after loading with precursor salts and calcination (step 2): SBA-B grains loaded with manganese chloride by impregnation then calcined at 400 °C (heterogeneous filling of the pores) and SBA-A loaded with manganese nitrate using the ‘two-solvent’ technique (homogeneous filling of the pores);

- after silica removal (step 3): after silica dissolution using a NaOH (2M) aqueous solution (see EDXS spectra in the insert), MnO2 nanowires of 4 nm in diameter, forming a self-supported bundle, are observed.

In the present study, we have decided to pattern manganese oxides in the pores of SBA-15 because several of these oxides, including MnO2, Mn2O3 and Mn3O4, labeled MnOx hereafter, are of high economical and environmental significance for their ion-exchange, molecular adsorption, electrochemical and magnetic properties. Furthermore, they all have the ability to catalyze redox catalytic reactions. For instance, Mn3O4, in which manganese ions of two different valencies are accessible in the same crystal [19], is an active catalyst for the oxidation of methane and carbon monoxide [20], the selective reduction of nitrobenzene [21] and the combustion of organic molecules which might be of interest to solve air pollution problems [22]. Finally, nanometer-sized MnOx particles are expected to display even better performances than bulkier particles because reduced sizes means an increase of specific surface area which can reasonably improve sensitivity toward oxygen [23]. The specific difficulties associated with the preparation and study of manganese oxides are summarized in Section 2. Section 3 will be devoted to practical in situ diffraction methods that we are developing to provide information about the crystallization of MnOx oxides in the confined environment constituted by the mesopores of SBA-15 hosts. Various in situ X-ray scattering and absorption experiments, performed at the French and the European synchrotron radiation facilities (LURE, Orsay and ESRF, Grenoble) will be described. Our motivation was to determine the effect of confining cylindrical spaces on the growth and structure of manganese oxide nanoparticles. We will show, in particular that, since phase transition temperatures depend, among other factors, on the oxide particles dimensions, the size of the pores can be used to control manganese oxides phase transformations.

2 Materials and methods

The characterization of MnOx nanocrystals is difficult because of the complexity introduced by the redox properties of manganese. Another difficulty arises from the existence, for a given oxidation state, of several polymorphs. For instance, 14 different polymorphs of MnO2 are known [24]. Structural information, necessary for the identification of manganese oxides used below, are summarized in Table 1.

Chemical analysis and N2 sorption analysis of selected samples calcined ex situ at 400 °C

| Silica | Mn/Si(at.) a | SBETb (m2/g) | VPc (cm3/g) | DBJHd (Å) |

| Non-porous silica | 0.1 | 380 | – | – |

| SBA-A | – | 600 | 0.70 | 40 |

| Mn-SBA-A ads. | 0.2 | 497 | 0.60 | 39 |

| Mn-SBA-A 2 solvents | 0.5 | 19 | 0.02 | – |

| SBA-B | – | 700 | 1.10 | 60 |

| Mn-SBA-B ads. | 0.4 | 587 | 1.00 | 58 |

| Mn-SBA-B 2 solvents | 0.5 | 402 | 0.60 | 60 |

a Chemical analysis performed at Solaize, CNRS, France.

b Determined for P/P0 ≈ 0.08–0.25, expressed by g of catalyst.

c Measured circa P/P0 = 0.98.

d Diameter of the mesopores corresponding to the maximum of the distribution curve obtained by applying the Barrett, Joyner and Halenda formula to the desorption branch of the N2 sorption isotherm.

2.1 Main MnOx oxides identified in our work

2.1.1 MnOx based on tetravalent manganese species

Even if the small radius of Mn(IV) cations (r = 0.53 Å compared to the radius of oxygen anions, R(O2–) = 1.26 Å, giving a r/R ratio of 0.42) could, in principle, favor the tetrahedral coordination, the octahedral coordination is stabilized by about 2.79 eV because of the 3d3 electronic configuration [25]. All the polymorphs of MnO2 can therefore be described with [MnO6] octahedra and they all correspond to a more or less close-packed network of oxygen anions differing by the ordering of Mn(IV) cations.

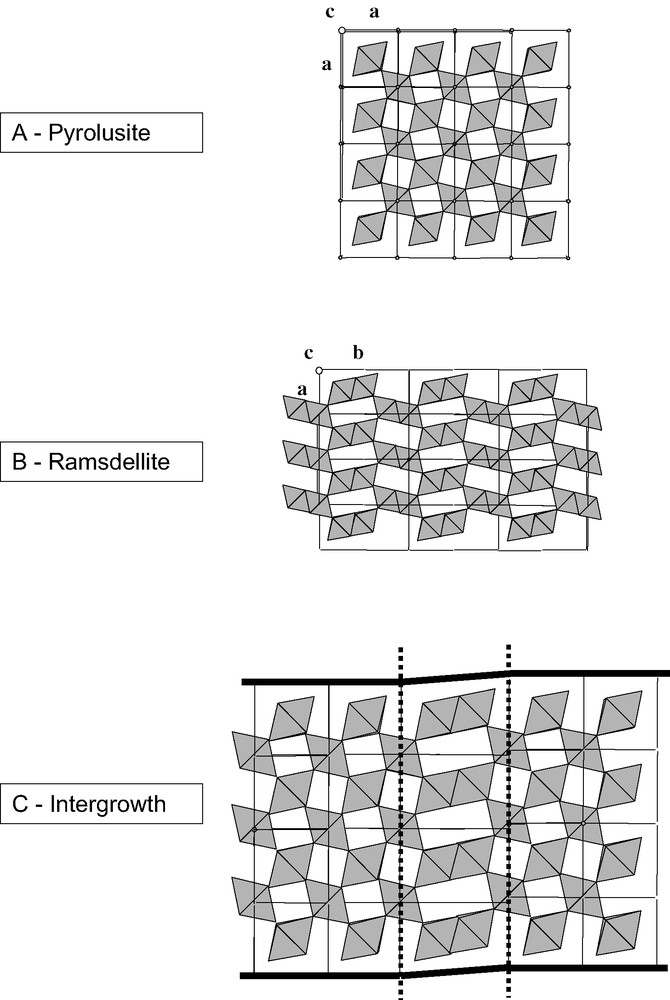

Pyrolusite β-MnO2 (Fig. 2A) has the rutile structure and is the most stable and dense polymorph (electronic density of 1.48 e–/Å3, calculated from the parameters of pyrolusite unit cell given in JCPDS# 72-1984). Infinite chains of [MnO6] octahedra share opposite corners. Each chain is further corner-linked to four similar chains. Another description can be obtained by considering oxygen anions forming a distorted close-packed array in which Mn(IV) cations occupy half of the octahedral sites. The vacant sites define channels running in the direction perpendicular to the chains. These channels are usually noted T(1,1) to recall that they are surrounded by chains formed by single [MnO6] octahedra. Note that in this structure, the number of edge sharing (ES) octahedra is identical to that of corner sharing (CS) octahedra.

Some MnOx polymorphs based on Mn(IV) cations: (A) pyrolusite, single chains of edge-sharing MO6 octahedra, (B) ramsdellite, infinite double chains of octahedra; (C) a ramsdellite/pyrolusite intergrowth.

Ramsdellite-MnO2 (Fig. 2B) is less dense (90% of the electronic density of pyrolusite) and has a structure closely related to that of pyrolusite. The anionic oxygen lattice is also compact hexagonal but the manganese cations distribution is different. Double chains of [MnO6] octahedra, in which octahedra are linked two by two by edges define T(1,2) channels. In pure ramsdellite crystals, the number of ES octahedra is lower than that of CS octahedra (2 versus 8).

The oxides related to natural nsutite are believed to result from a random intergrowth of ramsdellite and pyrolusite layers (Fig. 2C): double chains of octahedra being replaced by single chains. Their X-ray diffraction patterns are generally of bad quality and consist of sharp and broad diffraction lines. Their defective nature is due not only to ramsdellite/pyrolusite intergrowths (the so-called De Wolff defects) but also to microtwinning. A model proposed by Chabre and Pannetier, based on the analysis of diffraction patterns details, provides a quantitative evaluation of their structural disorder (% of microtwinning, % of ramsdellite/pyrolusite intergrowth) [24].

2.1.2 Higher oxidation states: manganese sesquioxide and hausmanite

Manganese sesquioxide, Mn2O3, exists in two forms: the stable α-Mn2O3 (bixbyite, JCPDS # 41-1442, three main diffraction lines at 3.84, 2.72 and 1.66 Å) and the metastable γ-Mn2O3 (defect containing spinel form, isomorph of hausmanite Mn3O4). A mild heating at 500 °C in air is enough to convert γ-Mn2O3 into α-Mn2O3. In α-Mn2O3, Mn(III) cations are surrounded by six oxygen atoms forming a distorted octahedron. All the octahedra are linked by sharing faces. The structure of γ-Mn2O3 is a defective spinel (AB2O4), structure. O2– anions form a close packed cubic lattice. Each unit cell contains 32 oxygen anions, eight octahedral and 16 tetrahedral interstitial sites. Mn(III) cations are distributed at random among these 24 potential sites.

Hausmanite Mn3O4 has the normal spinel (AB2O4) structure with 24 cations by unit-cell. Mn(II) and Mn(III) cations occupy, respectively, the tetrahedral (A) sites and the octahedral (B) sites.

2.2 Transformation of manganese nitrate into MnOx oxides upon calcination

The thermal and chemical events occurring during the decomposition in air of bulk manganese nitrate have been studied in detail by several teams. Like most manganese oxysalts, the end oxides are non-stoichiometric and easily transformed in various reduced forms. Based mainly on X-ray diffraction measurements, Dollimore and Tonge [26] have shown that Mn2O3 is the only reduced phase formed below 950 °C, whereas Mn3O4 is the main product above 950 °C. Detailed information about the progressive transformation of manganese nitrate into MnO2 before its further reduction has been obtained by Nohman et al. [27] using X-ray diffraction data complemented by IR measurements, thermogravimetry and by the analysis of the evolving gas products. Below 175 °C, Mn(NO3)2·4H2O is converted into its fully dehydrated and melted Mn(NO)2 form. Near 220 °C, MnO2 is formed, following the detection of a non-stoichiometric and unstable oxynitrate of possible formula MnO1.2(NO3)0.8 whereas Mn2O3 appears near 560 °C.

To check the thermal transformation experienced by manganese nitrate deposited on a non-porous silica reference in our experimental conditions, we have prepared a reference sample by depositing manganese nitrate on a non-porous silica (AEROSIL 380, DEGUSSA) for a Mn/Si ratio of 0.5. After ex situ calcination at 400 °C, 3 h, only wide angle diffraction peaks assigned to MnO2 were detected. After ex situ calcination at 700 °C, 6 h, a mixture of Mn2O3 and Mn3O4 was obtained. Fig. 5B compares the wide angle diffractograms of (a) a commercial Mn2O3 containing a small Mn3O4 contamination, and (d) the reference Aerosil 380 Degussa silica loaded with Mn-precursors after ex situ calcination at 700 °C, 6 h. More information about the diffractograms obtained with this reference sample are given below.

Comparison of wide angle diffractograms (H10 experimental station):

A – Collected in situ between 100 and 700 °C on a Mn-loaded SBA-A silica homogeneously filled with manganese nitrate.

B – References: (a) commercial Mn2O3, (b) Mn-loaded SBA-A silica calcined in situ up to 700 °C, (c) same sample after ex situ calcination at 700 °C, 6 h, (d) reference AEROSIL 380 Degussa silica loaded with Mn-precursors after ex situ calcination at 700 °C, 6 h.

2.3 Preparation and preliminary characterization of the Mn-loaded SBA-15 materials

Two distinct SBA-15 templates were used. The first one, labeled SBA-A, was obtained without hydrothermal treatment. The second, labeled SBA-B, was obtained after a standard hydrothermal treatment at 100 °C for 3 days [5]. As already detailed elsewhere [28], SBA-A and SBA-B silicas differ by their overall porous volume and mesopore diameters and also by their amount of disordered intrawall micropores. The main characteristics of selected samples: their chemical and N2 sorption analyses before, after Mn-loading and after ex situ calcination (400 °C) are gathered in Table 2.

Crystallographic characteristics of selected manganese oxides polymorphs

A first series of Mn-loaded samples were obtained using a conventional adsorption technique. The second series of samples was prepared with the same SBA-A and SBA-B silicas but using an original ‘two-solvent’ impregnation method. This method, detailed in Ref. [17], is based on a volume of aqueous solution set equal to the porous volume of the silica mold (determined by N2 sorption) and therefore derives from incipient wetness impregnation techniques. In the specific case of SBA-15 silica hosts, we have found it necessary to suspend dehydrated silicas in n-hexane, an organic solvent poorly miscible with water, before contacting them with an aqueous manganese nitrate solution of volume set equal to the silica porous volume.

After ex situ calcination at 400 °C, the two series of samples were investigated by combining textural (N2 sorption) and local (Transmission Electron Microscopy, TEM, coupled with high resolution, HR, and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy, EDXS) information. To illustrate the results obtained, some characteristic TEM images are presented in Fig. 1, step 2. In short, the samples obtained by adsorption (first series) are highly heterogeneous and contain: (i) MnOx particles inside and outside the silica grains, (ii) both filled and empty mesopores, (iii) different MnOx oxides. In contrast, the samples obtained by the ‘two-solvent’ impregnation technique (second series) are quite homogeneous and contain mainly MnOx nanoparticles confined within the porosity of the SBA-15 templates. N2 sorption experiments show that the specific surface area and porous volume are reduced. On SBA-A, a very important decrease of the porous volume (97%) suggests that the nitrogen molecules can only probe the external surface of the silica grains. This last observation is difficult to analyze by itself because some MnOx particles, generated by calcination, might block the entrance of the silica mesopores. However, by EDXS, a constant atomic Mn/Si ratio (0.50 ± 0.03) was found on different parts of a given silica grain, and, also, on at least five different Mn-loaded grains. We can therefore safely consider that the porosity of the SBA-A mold is homogeneously filled with manganese oxide particles in our experimental conditions.

A definitive argument for complete filling of the pores is obtained after silica dissolution with NaOH (0.2 M, Fig. 1, step 3). When silica is fully eliminated (EDX spectra in the insert of Fig. 1), the 2D hexagonal order is lost but elongated nanoparticles of MnOx (3–4 nm in diameter, for a SBA-15 hard template with mesopores of 4 nm in diameter, and about 1 μm long) are revealed by electron microscopy. With selected-area electron diffraction (SAED; data not shown), diffraction circles are observed, showing that these nanoparticles are polycrystalline. They form by the association of smaller nanocrystals sintered within the mesopores. Heating treatments aimed at inducing a further recrystallization, to transform these nanoparticles into monocrystalline domains before silica removal, are still under progress and may be highly interesting from a technical point of view. Finally, the nanoparticles nucleated in the mesopores form a self-supported bundle. Disordered interconnections between adjacent particles should exist and probably derive from the patterning of manganese oxide in disordered intrawall defects of the SBA-15 mold, as already observed during the nanocasting of other oxides [14].

The ‘two-solvent’ technique that we have developed is extremely simple, yet very effective and allows practically a complete filling of the pores whereas mesopores are generally partially occupied by the inorganic objects with other techniques. For instance, in a recent paper [14], despite the specific use of microwave digested SBA-15, only 40% of the mesoporous volume of the SBA-15 host was finally occupied by oxide particles. In the following sections, we will see that the quality of subsequent studies of oxide nanoparticles derived from SBA-15 silicas is greatly improved. We will also show that obtaining homogeneous samples helps understanding how the structural features of the silica host relate to the nature and crystallinity of the inorganic objects patterned in the mesopores.

2.4 Methods

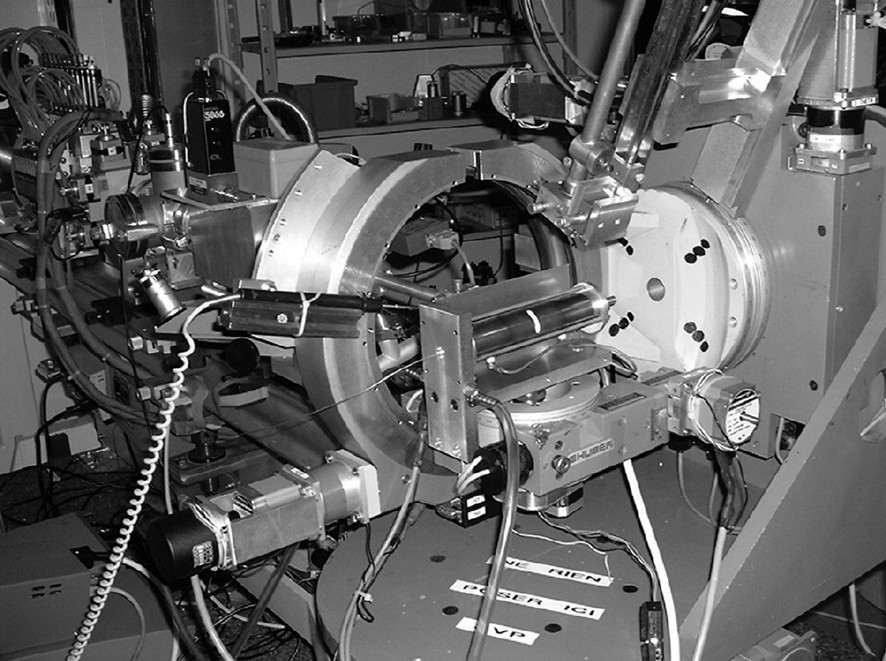

After depositing Mn-precursors by the ‘two-solvent’ technique, various in situ X-ray scattering and absorption techniques, accessible at the French synchrotron radiation facility (LURE, Orsay) were used to understand the salient features of the MnOx nanowires crystallization patterned in SBA-A and SBA-B silicas. We have used experimental stations of both the DCI (H10 (Fig. 3), D42) and Super ACO (SU23) storage rings.

Set-up used on the H10 experimental station. The in situ heating cell has been used between 25 and 700 °C (P.A. Albouy, ‘Laboratoire de physique des solides’, Orsay, France).

Long range structural information was obtained by Small and Wide Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS and WAXS, Figs. 4 and 5) and Anomalous Wide and Small Angle X-ray Scattering (AWAXS and ASAXS, data not shown) whereas local structural information was collected by Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS, Fig. 6) at the Mn K edge. X-ray Absorption Near the Edge Spectra with hard (Mn K edge) and soft (Mn LIII/LII edges) (XANES, Figs. 7 and 8) X-rays were collected to obtain additional electronic information. Finally, Fig. 9 shows a comprehensive representation of X-ray scattering over a wide lengthscale range (0.1–100 nm), as recorded thanks to three different experimental stations (European Synchrotron radiation Facility, ESRF, ID2, Grenoble; LURE D43 and H10).

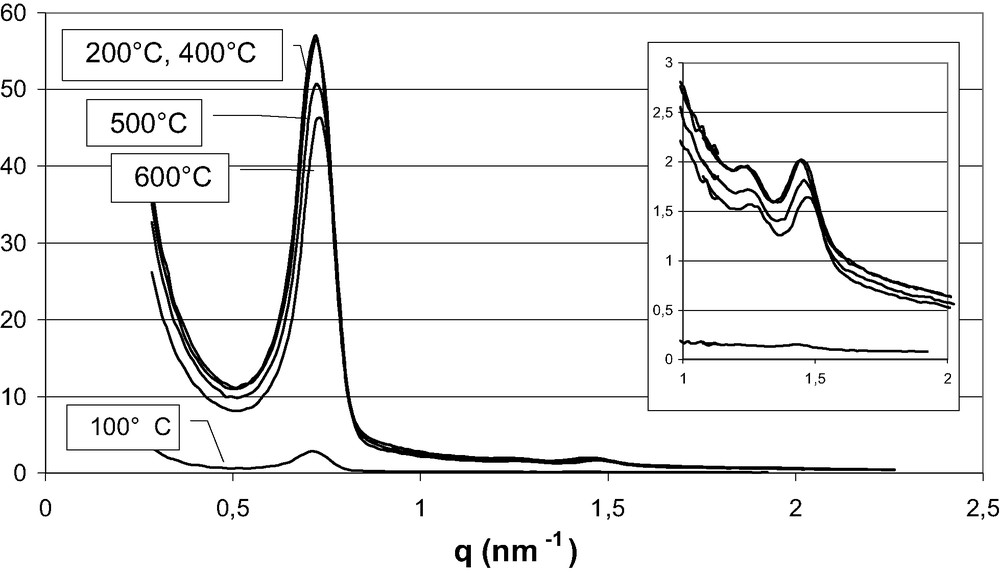

Thermal evolution of the diffraction observed at small angles (H10 experimental station) on a SBA-A silica homogeneously filled with manganese nitrate.

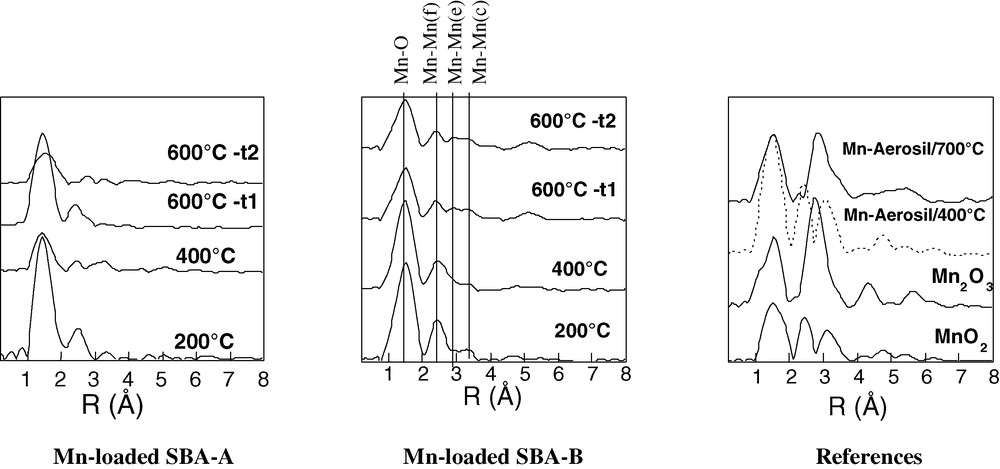

EXAFS spectra measured recorded at room temperature on reference samples and at 200, 400 and 600 °C on SBA-A and SBA-B silicas homogeneously filled with Mn-precursors.

Spectra recorded after two times of analysis at 600 °C are also compared (t1, upon reaching the desired temperature, t2 after 1 h of annealing at 600 °C).

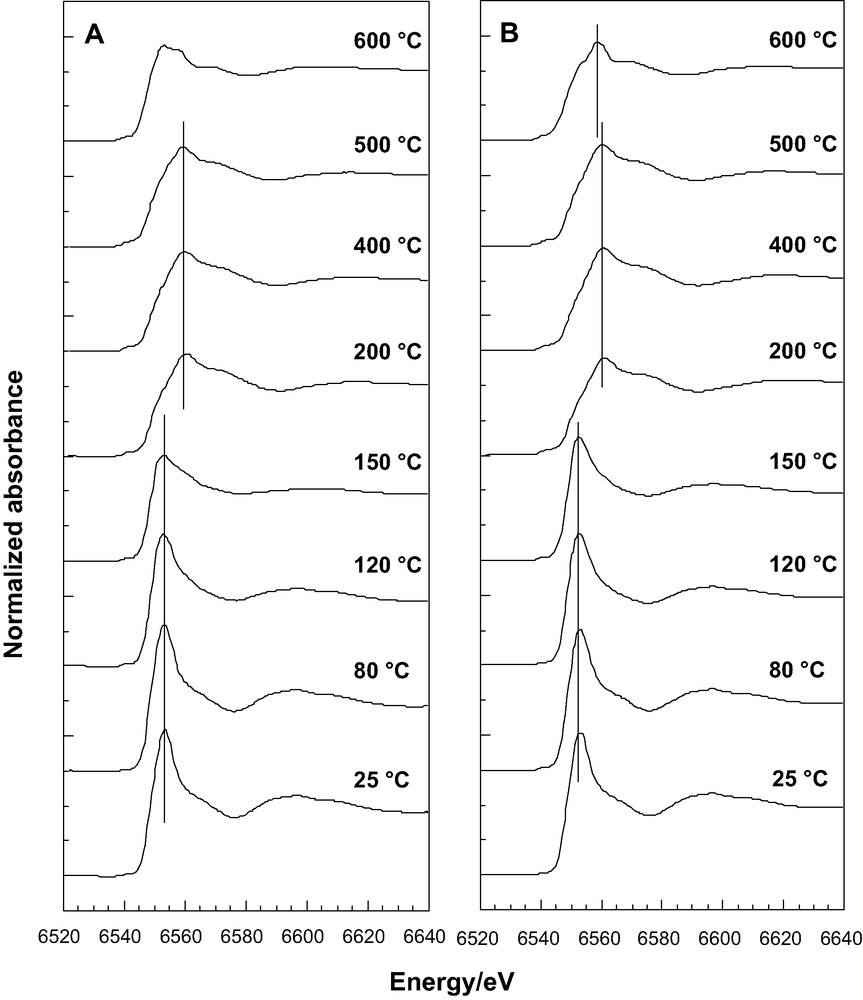

X-ray absorption spectra near the Mn K edge (XANES) as a function of temperature on (A) Mn-loaded SBA-A; (B) Mn-loaded SBA-B silicas homogeneously filled with Mn-precursors; (C) Comparison of the spectra recorded at 160 °C on SBA-B (___) and 150 °C on SBA-A (---).

X-ray absorption spectra near the Mn L edge recorded under vacuum on two commercial samples (Mn2O3 and MnO2), Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B samples (A: as prepared sample, B: after heat treatment at 120 °C).

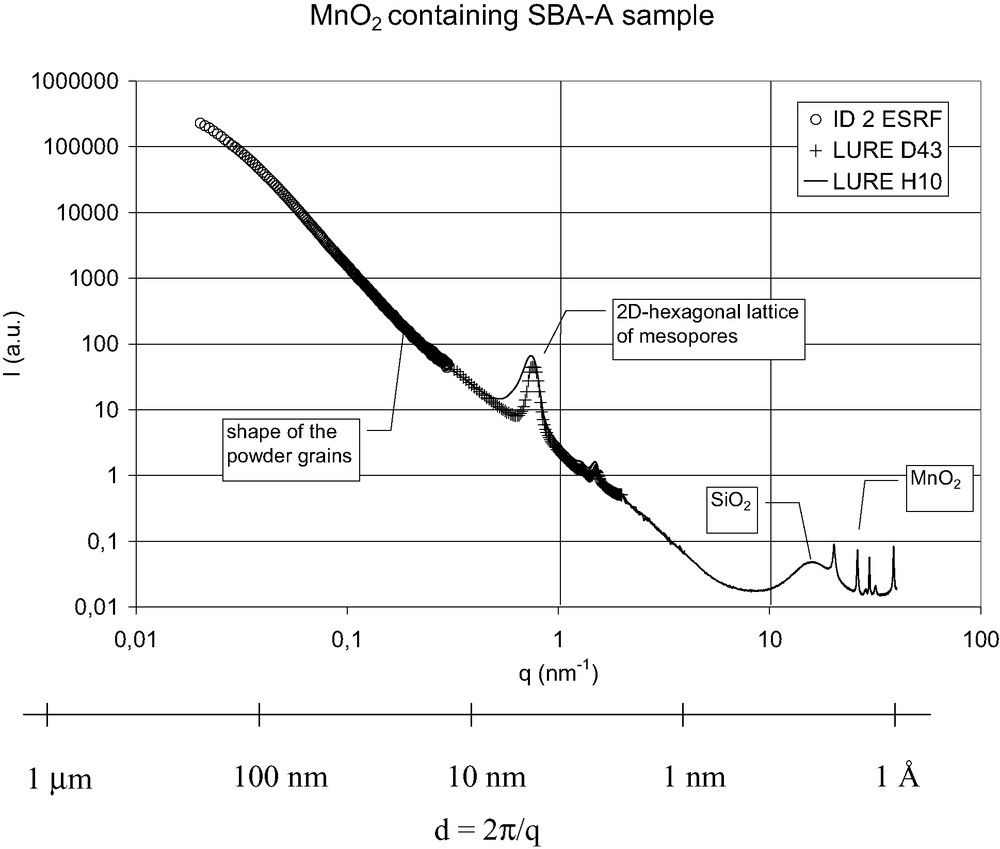

SBA-A sample filled with MnO2 after ex situ calcination at 400 °C. The different contributions to the X-ray scattering on a wide scale-length range (1 Å to 100 nm) were recorded thanks to three different beam-lines.

3 Main results obtained using diffraction and absorption techniques upon in situ calcinations

3.1 SAXS measurements

The preservation of the 2D hexagonal structure upon calcination has been established by SAXS measurements. These measurements were first performed on blank SBA-A and SBA-B silicas. From room-temperature to 320–350 °C, no increase in the diffraction peaks line-width is observed, indicating that the 2D hexagonal ordering is retained. The positions and the relative intensities of the peaks do not significantly change. The unit-cell parameter remains constant.

The overall intensity of the diffractograms recorded at room temperature on uncalcined Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B materials is lower than that observed with blank silicas. The porosity is filled with hydrated Mn(II) species and the resulting electron density contrast between the pores and silica walls is lower than that of the blank silicas. This overall intensity remains fairly constant below 150 °C. Above this temperature, an abrupt but very small contraction (1%) of the 2D hexagonal lattice is observed. At the same temperature, a clear increase of the overall intensity occurs but the relative intensities of the different peaks are not altered (Fig. 4). These results are fully consistent with a series of experiments performed on another experimental station (D43) and reported in Ref. [17]. The intensity of the (10) peak is directly proportional to the square of the electron density contrast between the silica walls, ρwall, and the material inside the porosity, ρpore: I(10)∝ (ρwall − ρpore)2. The electron density ρwall is about 0.66 e–/Å3 (taking a massic density of 2.2 g/cm3 for bulk amorphous silica) and the electron density of water is 0.33 e–/Å3. At low temperatures, the electron density difference is quite low because the hydrated manganese species give an electron density ρpore close to ρwall of silica. ρpore is indeed larger than 0.33 e–/Å3 (pure water) and probably less than ρwall, with ρwall – ρpore ≈ 0.1–0.2 e–/Å3. Upon heating, ρpore increases because water is progressively eliminated. At high temperature, if the pores are filled with MnO2 nanowires, a value ρpore = 1.48 e–/Å3 can be expected (calculated from the unit cell size of pyrolusite) and ρwall − ρpore = –0.82 e–/Å3.

3.2 WAXS measurements

The nature of the manganese oxides formed upon calcination has been determined by WAXS. Fig. 5A shows the WAXS diffractograms recorded between room temperature and 700 °C on the Mn-loaded SBA-A sample. The very broad diffraction near q = 15.7 per nm observed at all temperatures, is the signature of the amorphous silica. All the other diffraction lines can be assigned to MnOx particles. The lines appearing at 200 °C are assigned to pyrolusite β-MnO2 particles. These peaks are broader than the experimental resolution (compare their line-width to that of a well crystallized Mn2O3 presented in Fig. 5B(a)). Very small and/or highly defective pyrolusite crystallites are then detected. The diffraction peaks observed at 400 °C can be indexed using a quadratic unit cell with a = 4.428 ± 0.003 Å and c = 2.875 ± 0.007 Å unit cell parameters. The a unit cell parameter is larger than that of perfect pyrolusite. This is indeed expected for defective pyrolusite crystals containing structural defects of ramsdellite type. The presence of pyrolusite and ramsdellite intergrowth is confirmed by other features: the first diffraction peak, indexed (110), is much smaller and broader in experimental diffractograms than in the calculations of the structure factor of pyrolusite that we have performed and reported in [17]. The observed line-width reflects both the small size of the β-MnO2 particles and the dominant contribution of defects. From the line-width, using the method proposed by Chabre and Pannetier [24] the proportion of defects in β-MnO2 pyrolusite nanowires was estimated to circa 10% in the Mn-loaded SBA-B sample treated in situ up to 400 °C. Other peaks, in particular those indexed (210) and (220) also deserve attention. On SBA-B, they only appear as shoulders on the more intense (111) and (211) peaks, respectively. On SBA-A, all the diffraction peaks are so broad that these shoulders cannot be detected. This indicates that the MnOx crystallites formed in a SBA-B mold are significantly larger than those detected in SBA-A, as expected because of the diameter of primary mesopores (7 and 4 nm, respectively).

On Mn-loaded SBA-A, the diffractions appearing at 600 °C are mainly due to Mn2O3. Using the indexations proposed in JCPDS # 41-1442, a larger a value than that observed for bulk oxide Mn2O3 at room temperature (a = 9.41 compared to 9.45 Å) is observed after heating to 700 °C. After cooling down to room-temperature, the Mn2O3 nanoparticles confined inside the mesopores of SBA-A keep a lattice parameter a = 9.43 Å, that remains slightly larger than that of bulk Mn2O3. Furthermore, on a reference sample prepared with an AEROSIL non-porous silica, after ex situ heating at 700 °C, 6 h and cooling down to room temperature, the Mn2O3 lattice parameter (a = 9.41 Å) remains identical to that of bulk commercial Mn2O3. These observations indicate that thermal dilation properties are different for oxides within the mesopores and in bulk, probably because of the presence of structural defects. More puzzling information is given by Mn3O4 diffractions peaks: hardly detected after 1h of in situ heating at 700 °C (Figs. 5A, B(b)), they are stronger after ex situ heating at 700 °C, 6 h with both SBA-A and SBA-B but remain low with the reference AEROSIL Degussa (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the Mn2O3 → Mn3O4 phase transformation is thermodynamically possible at 700 °C and is kinetically favored when smaller Mn2O3 particles are involved.

3.3 AWAXS and ASAXS measurements

Anomalous diffraction spectra at the manganese K-edge were recorded, both at wide and small angles. At wide angles, a strong anomalous effect on some of the Bragg peaks of the MnO2 nanocrystals has been evidenced and nicely reproduced on simulated spectra [17]. At small angles, the overall intensity of the Bragg peaks due to the 2D hexagonal lattice varies when changing the energy of the incident X-rays around the Mn K-edge and follows absorption variations. Unfortunately, no significant changes in the relative intensities of the (10), (11) and (20) peaks could be detected.

3.4 EXAFS at the Mn K edge

EXAFS is a radial technique that gives information about bond lengths around a given element, even if this element is present in small proportion and is part of an amorphous or poorly organized phase. However, it is difficult to distinguish closely related topologies by EXAFS without knowing with great precision the coordination numbers N. This determination was difficult with our samples because of the presence of defects (intergrowth but also cationic vacancies and/or non-stoichiometries associated with the presence of Mn cations in different oxidation states). Structural variations have anyway been evidenced on the Fourier transform of the EXAFS spectra, the so-called radial distribution functions (RDFs).

After in situ heating at 200 and 400 °C, with both Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B samples, three well separated peaks of variable intensities are observed, each one corresponding to given neighbors in the coordination shell surrounding manganese atoms (Fig. 6). Mn(IV) species are surrounded by oxygens as first neighbors and other manganese species as second ones. On these spectra and on that of a commercial MnO2 sample, the second and third RDF peaks are, respectively, assigned to edge (Mn–Mn(e)) and corner-sharing (Mn–Mn(c)) [MnO6] octahedra [29]. The relative intensities of the two peaks are known to change if a ramsdellite framework develops at the expense of the pyrolusite one. With Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B samples treated at 400 °C, the relative magnitude of the second RDF peak compared to the third lies between the ones reported in literature for ramsdellite and pyrolusite, as expected because of the presence of structural intergrowth. This confirms that, in our samples, irregular alterations of pyrolusite are linked by ramsdellite domains. Another interesting peak is located near 4.8 Å on the RDF of the reference MnO2 and the Mn-loaded SBA-B, but is absent on SBA-A. Even low, this peak has a structural reality as it gives information about the gradual long range crystallization of MnO2. Indeed, the potential encountered by a photoelectron – and hence the wave amplitude – depends on atomic positions through space. The amplitude of an EXAFS signal is known to be magnified when an atom lies perfectly aligned with a central atom and a back-scattering one. This is called the focusing effect which occurs when [MnO6] octahedra share corners [30]. The shared oxygen atom can act as a lens. The weakness of this peak indicates the low crystallinity of MnO2 particles in the Mn-loaded SBA-A sample.

To analyze the RDF measurements performed after in situ calcination at 600 °C, it is necessary to examine first the signal of a commercial Mn2O3 sample. The first peak on its RDF, attributed to the oxygen first shell is broad and presents a distinct shoulder on its left part. Because of the Jahn–Teller effect expected for a nd4 low spin electronic configuration, more than one Mn–O distance are present. Furthermore, only one signal can be assigned to Mn–Mn distances. This signal corresponds to a distance intermediate between those attributed to corner-sharing and edge sharing octahedra. In Mn2O3, all the [MnO6] octahedra are face-sharing (three edges, Mn–Mn(f) on Fig. 6). With this analysis, the RDFs recorded at 600 °C on both the Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B samples indicate the coexistence of MnO2 and Mn2O3. On SBA-B, the RDF recorded after 1 h of annealing at 600 °C is identical to the first measurement (not shown) but this is not the case with SBA-A (Fig. 6). With this peculiar sample, the first peak attributed to the oxygen first shell becomes weaker and much broader with time. This aspect reveals distorted octahedra, with more than two Mn–O distances. Similar spectral shapes have been reported for Mn(III) and Mn(IV) cations coexisting in the spinel structure [31]. In that case, the EXAFS oscillations were reported to exhibit a destructive interference explaining the low apparent peak height of the RDF.

3.5 XANES measurements

In XANES measurements at the Mn K-edge, the energy of the main peak, called the ‘white line’, is determined by the binding energy of the 1 s electron. For a given environment, this energy is correlated, in particular, with the oxidation state of the absorber atom because the binding energy of any electron increases when surrounding electrons are removed, i.e. when the atom is oxidized. Furthermore, the linear dependency of the Mn edge position for reference Mn oxides has already been demonstrated [32]. XANES spectra, measured in situ between 25 and 600 °C with Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B samples, are compared in Fig. 7A, B. The spectral shape observed at 25 °C is typical of Mn(II) species surrounded by an octahedron of oxygen atoms, as already observed for Mn(II) cations introduced as impurities in oxide glasses [33]. The low amplitude of the pre-edge, corresponding to a forbidden 1s → 3d transition, indicates that the Mn(II) cation occupies a nearly centrosymmetric position. A positive shift of +7 eV of the white line is observed between 150 and 200 °C. On average, Mn(II) species are transformed into Mn(IV) ones [34], as expected because of the transformation of precursor Mn(H2O)62+ species into MnO2 oxide. At 120 and 150 °C, with SBA-A (Fig. 7A), spectra are significantly different whereas with SBA-B (Fig. 7B), they remain identical. Furthermore, the spectrum recorded at 150 °C with SBA-A (dotted line, Fig. 7C) is identical to the spectrum recorded at 160 °C with SBA-B. The thermal transformation occurs then at a lower temperature in SBA-A than in SBA-B. Between 200 and 500 °C, neither the shape nor the position are altered indicating that both the electronic state and the nature of the coordination sphere of Mn(IV) species remain unchanged. However, above 500 °C a second thermal transformation is observed. The formation of Mn(III) species, i.e. of Mn2O3, is indicated by the energy of the white line, intermediate between those attributed to Mn(II) and Mn(IV) species. At 600 °C, it is worth to note that the spectra recorded on SBA-A and SBA-B are not the same, pointing again for a major role of mesopore diameter on the thermal phase transformation experienced by confined oxide nanoparticles.

Recent theoretical and instrumental advances have motivated several studies dedicated to the application in heterogeneous catalysis of X-ray absorption spectroscopy at low energy [35]. This new approach allows experiments at the K edges of light elements such as carbon or oxygen [36,37] and/or at the L edges of 3d transition metals [38,39]. In the case of Co [38] and Mn [39] based catalysts, the theoretical analyses associated with a set of data collected on real catalysts, have clearly shown the importance of 2p (LIII,II) X-ray absorption spectroscopy as an element specific valency probe. Fig. 8 shows a set of preliminary experiments that we have performed on Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B samples.

The spectra presented in Fig. 8A were recorded after 6 h under a vacuum of 10–8 bars. With manganese oxide references, MnO2 and Mn2O3, information regarding the oxidation state of manganese can be obtained through the LIII/LII intensity ratio. Obviously, this experimental data agrees with the average value given in reference [39], i.e. 2.6 for Mn2O3 (Mn(III)) and 2.1 for MnO2 (Mn(IV)). The spectra recorded on Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B are similar, showing that the valency of manganese species as well as their symmetry are identical. They are, however, significantly different from those of the two references, and they indicate qualitatively an averaged oxidation state lower than III. After heating at 120 °C, 1 h (Fig. 8B), the two references spectra remain almost unchanged. On the spectra of Mn-loaded SBA-A and SBA-B, there is no clear variation in the relative intensity of the LIII and LII contributions. This indicates that the thermal treatment applied here can be expected to have a limited effect on the average oxidation state of Mn precursors. However, a more pronounced loss of resolution of the LIII doublet is observed on SBA-A than on SBA-B. This last observation confirms that the reactivity of manganese precursors is enhanced when the confined space defined by the host mesopores is reduced.

3.6 X-ray scattering over a wide lengthscale range (0.1–100 nm)

X-ray scattering measurements within the wide range 0.1–100 nm were needed because our materials exhibit structures at several length scales. As illustrated in Fig. 9 for the Mn-loaded SBA-A sample calcined ex situ at 400 °C, 6 h, different contributions can be distinguished. The scattering signals of amorphous silica walls and MnO2 nanowires arises at a few Å scale. The 2D hexagonal lattice of mesopores gives Bragg peaks between 1 and 10 nm. A strong contribution from the powder grains is measured up to length scales as large as 100 nm, only accessible at very small angle X-ray scattering on experimental stations such as the ID2 beam-line at ESRF. This background is related to the shapes and dimensions of the silica grains, which are often polydispersed as seen by TEM. It is already present for SBA-A and SBA-B silicas alone, and is enhanced after their loading with MnOx, due to the increase of electronic contrast with air. This background is however difficult to analyze quantitatively because of the grain size polydispersity and would be highly decreased with silica monoliths.

4 Conclusions and outlook

Fast progress has been made in the oxide nanowires research area very recently. It seems however clear that much more is likely to come. If nanocasting procedures have been used to pattern different oxides, relatively little effort has gone toward a better understanding of the factors that control their crystallinity. Significant breakthroughs will be obtained if we can play with the flexibility of the nanocasting techniques, intimately linked to different parameters (characteristics of silica molds, nature of metallic precursors, optimized conditions of thermal transformation into oxides).

The technical difficulties associated with manganese oxides have been described in the second section of this manuscript. These oxides were selected because of their challenging aspects, the problems met in their study being due both to the redox properties of manganese and to the multiple oxide polymorphs found for each manganese oxidation state. The SBA-15 materials that we have used and their Mn-loaded derivatives, as well as preliminary characterization were also detailed in this section.

In the last section, the in situ characterization techniques currently developed in our group have been described. These in situ techniques span the full range of atomic length scales from short range (EXAFS, XANES) to long range (X-ray diffraction). Using these techniques, we have shown that: (i) elongated and monophasic MnO2 nanoparticles can be generated within the pores of SBA-15 silicas, (ii) the thermal reduction of these nanoparticles, which leads to mixtures of Mn2O3 and Mn3O4, is significantly affected by the mesopore diameters of the silica template (observed both in the EXAFS and XANES in situ studies), (iii) on the Mn2O3 nanoparticles formed above 600 °C on SBA-A, size-induced structural modifications, associated with changes in structural parameters and thermal dilation properties, have been observed. We have also demonstrated that in situ conventional diffraction methods are limited since they only probe long-range order. They are therefore insensitive to the structure of the nucleation sites formed in the early steps of the reaction and too small to be observed. It is therefore useful to combine in situ XANES, EXAFS and X-ray diffraction techniques simultaneously upon calcination, because this is the only way to correlate changes over short and long ranges during the crystallization of oxide nanowires. Special attention will be paid now to the structural defects of confined oxide nanoparticles (intergrowth, twinning, grain boundaries). Only a comprehensive approach combining classical characterization techniques such as high resolution electronic microscopy and synchrotron radiation techniques will allow us to observe such modifications at the atomic scale. These remarks are not limited to oxide nanowires patterned by 2D hexagonal silicas and may apply as well: (i) to oxide nanowires patterned with other inorganic molds (the In2O3 nanowires grown in cubic silica reported by Yang et al. [40] for instance), (ii) to other nanowires obtained by nanocasting (the recently reported Zn1–xMnxS quantum wires [41] for instance).

Acknowledgements

Professor M. Che and M. Breysse (LRS director) are gratefully acknowledged for their constant help and support. The authors are also grateful to M.D. Appay and P. Beaunier (MET), P. Parent and C. Laffon (soft X-rays), P. Panine (ESRF), F. Villain (XANES, EXAFS), D. Thiaudière and M. Gailhanou (AWAXS, ASAXS). Stimulating discussions with P.A. Albouy and permission to use the heating cell of the L.P.S. are also gratefully acknowledged.