1. Introduction

The Anatolian–Iranian plateau is one of the regions where active continent–continent collision is currently taking place. Previous studies to date [Sengor and Kidd 1979, Dewey et al. 1986] have shown that collision occurred between Eurasian and Arabian continents, resulting in the formation of an extensive (150,000 km2) high plateau with an average elevation of 2 km above sea level [Ahmadzadeh et al. 2010]. The presence of potassium-rich volcanic rocks in this area is important, because these rocks occur in a variety of tectonic settings including continental convergent margins [Gill et al. 2004], and syn- to post-collisional tectonic settings as in Anatolia and Tibet [Deng et al. 2012, Conticelli et al. 2013].

Alkaline rocks from this area contain various types of xenoliths, such as pyroxenite, gabbro, diorite and hornblendite xenoliths. Amphibole is frequently observed in xenoliths since it may occur in a wide range of pressure and temperature and is among the main constituents of mafic and ultramafic igneous and metamorphic rocks. Amphibole is moreover one of the most suitable minerals for thermobarometry estimates [Putirka 2016].

Hornblende-rich xenoliths have been reported from several locations worldwide; e.g., northeast of Iran [Yousefzadeh and Sabzehei 2012], central Mexico [Blatter and Carmichael 1998], Iberian Peninsula [Capedri et al. 1989], western and central Europe [Downes et al. 2001, 2002, Carraro and Visonà 2003], and central Spain [Orejana et al. 2006]. The majority of the hornblendite xenoliths are related to the host volcanic rocks [Witt-Eickschen and Kramm 1998] while some others are witnesses of a metasomatized mantle or cumulates from older magmatic events [e.g., Frey and Prinz 1978, Irving 1980, Capedri et al. 1989, Saadat and Stern 2012, Rajabi et al. 2014, Su et al. 2014, Kheirkhah et al. 2015].

In the study area, volcanic rocks have been previously investigated in terms of their geochemistry and petrology by Khezerlou et al. [2008] and Ahmadzadeh et al. [2010]. Moreover, pyroxenite [Khezerlou et al. 2017], gabbro and diorite xenoliths [Khezerlou et al. 2020] have been studied in terms of their geochemistry, isotope, and mineralogy. Studies of volcanic rocks and xenoliths in the study area have shown that their constituent magmas originate from a metasomatized mantle. However, no such information is available about the hornblendite xenoliths. Studying hornblende-rich rocks occurring in volcanic rocks can provide valuable information about their origin and the magmatic history of the investigated area. Hence, the present research was conducted to investigate the petrographic and geochemical characteristics of the hornblendite xenoliths and their host volcanic rocks from the northern part of Uromieh Dokhatar magmatic belt. Moreover, major and trace element data, and 143Nd/144Nd and 86Sr/87Sr isotopic ratios were evaluated to determine the petrogenesis, and establish the relationship between the magmatic source of these xenoliths and their host volcanic rocks.

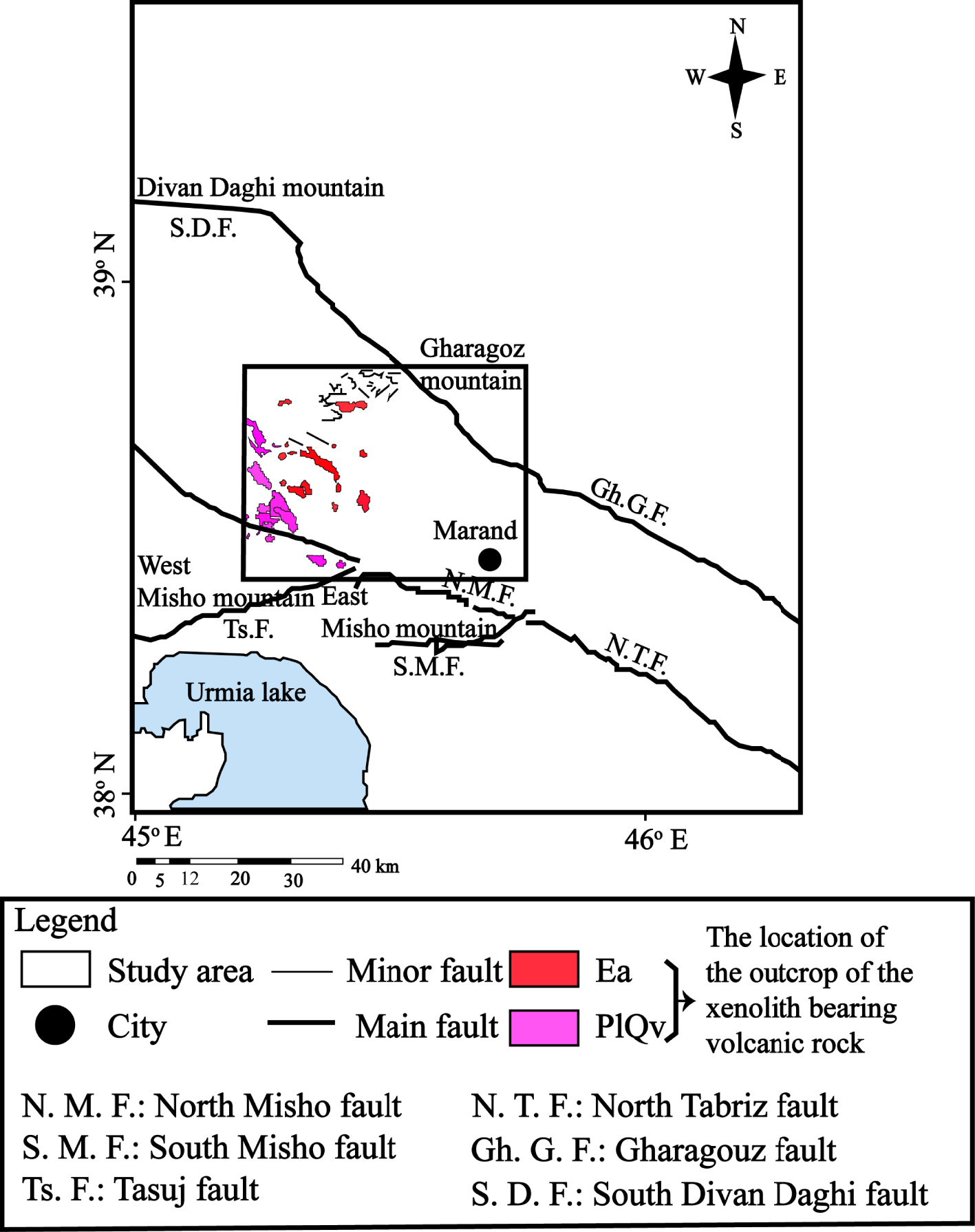

Tectonic map of the investigated area, showing the location of the outcrop of the xenoliths-bearing volcanic rocks [modified after Khezerlou et al. 2020]. Ea (Eocene, pyroxine andesite)–PlQv (Plio-Quaternary, volcanic).

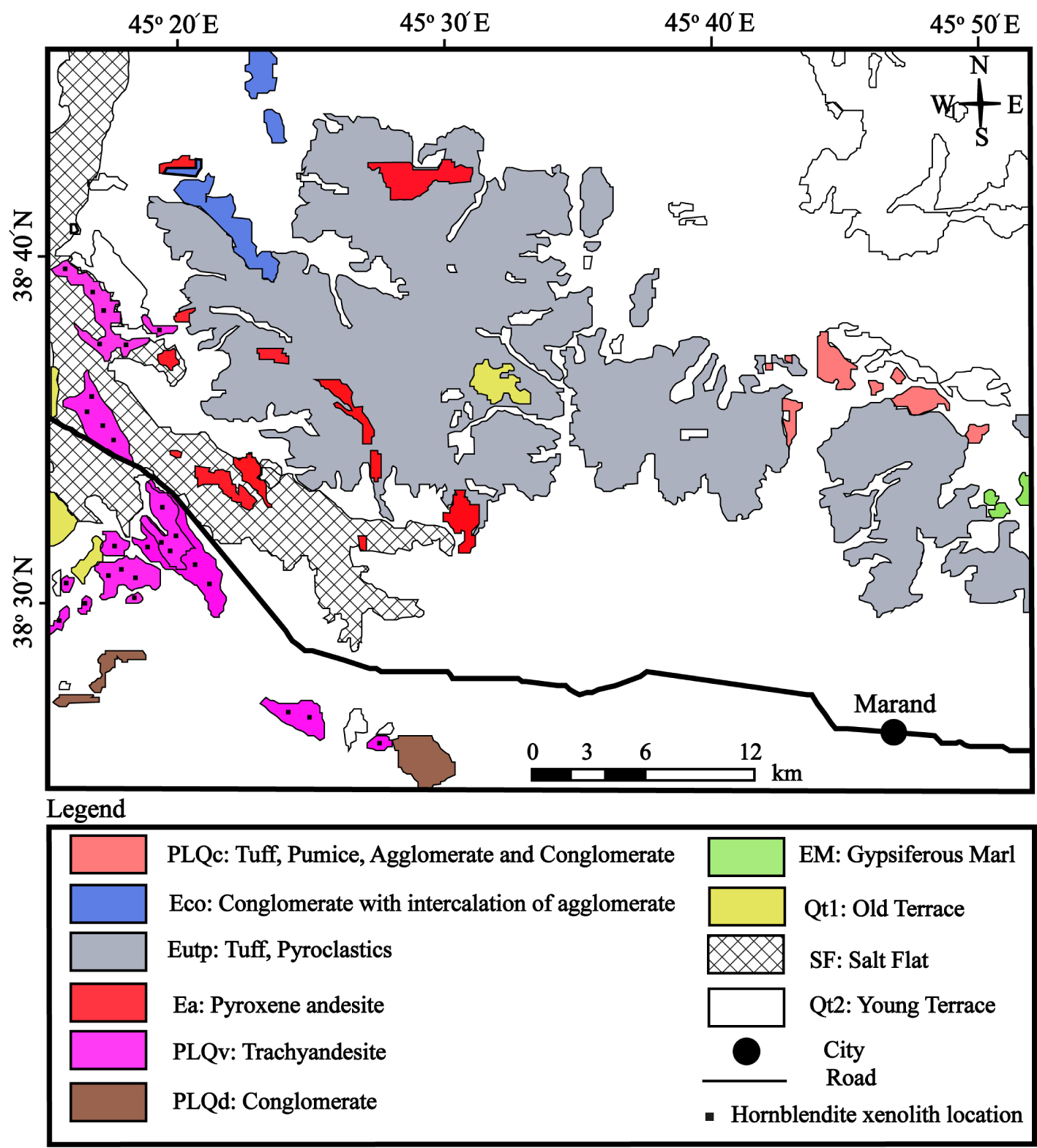

Geological map of the investigated area. (Simplified from the 1:100,000 geological maps of Marand, Jolfa, Gharezyaadin and Tasuj) [modified after Khezerlou et al. 2017]. Location of sampling includes Ea and PlQv.

2. Geological setting

The Neotethys subduction process that occurred beneath Central Iran during the upper Cretaceous and Paleogene and the collision process between the Iran and Arabia Platforms created four structural zones in Iran. These zones are; the High Zagros belt, the Sanandaj–Sirjan zone, the Uromieh Dokhtar magmatic belt, and the Zagros folded zone [Alavi 2004]. The study area is located in the northernmost of the Uromieh Dokhtar magmatic belt, characterized by a magmatic activity which started during the late Cretaceous and was active from Eocene to Quaternary. The peak magmatism of this zone occurred during Eocene [Farhoudi 1978, Emami 1981, Alavi 2004]. However, it ceased for a short time and started again during the upper Miocene to Plio-Quaternary [Omrani et al. 2008]. The volcanic rocks from the northwest of Marand overlie the Upper Miocene clastic and evaporitic rocks, being possibly Plio-Quaternary in age.

The study area is located between the main faults of the region including North Tabriz (N. T. F), Misho (N. M. F and S. M. F), and Tasuj (Ts. F) faults to the south and Garagouz (Gh. G. F) and South Divan Daghi (S. D. F) faults to the north (Figure 1).

Field surveys revealed a wide range of volcanic and volcanoclastic rocks outcropping in this area (Figure 2). The volcanoclastic rocks from the study area include agglomerate, breccia, and tuff lithologies. The volcanic rocks of the study area are identified in Figure 2 by PLQv (trachyandesite) and Ea (pyroxene andesite) acronyms. In detail, in the area of PLQv, the volcanic rocks also include basanite, tephrite, and basalt trachyandesites, in addition to trachyandesite which is the dominant rock type. There are also tuffs in this area which are in contact with trachyandesite volcanic rocks. In some locations, 2–3 m thick layers of volcanic ashes with a trachyandesite composition are observed in contact with tuffs [Khezerlou et al. 2008]. Xenoliths occurring in this area (PLQv) are gabbros, diorites, hornblendites, lamprophyres, and pyroxenites hosted by trachyandesites and basalt trachyandesites. In the area of Ea (pyroxene andesite), the volcanic rocks include leucitite, leucite–basanite, leucite–tephrite, basanite, tephrite, basalt trachyandesites, trachydacite, and dacite. Xenoliths occurring in this area (Ea) are gabbros, diorites, and pyroxenites hosted by basalt trachyandesites.

Several dykes outcrop in the study area. They are mostly ultrapotassic in composition. Also, some lamprophyric dykes between 9 and 11 Ma (Late Miocene) in age occur in the study area in Sorkheh, Iran [Aghazadeh et al. 2015].

In the southern part of the study area, in the Misho Mountain (Southwest of Marand), some outcrops of mafic rocks including gabbro, diorite, anorthosite and olivine gabbro occur, sometimes associated to ultrabasic rocks ranging from peridotite to highly serpentinized pyroxenite. These rocks are located above the Kahar Formation, and are covered by a weathering shell. Thus, their relative age is estimated to be younger than that of the Kahar Formation and older than the Permian [Azimzadeh 2013]. In this regard, Saccani et al. [2013] ascribe these rocks to the Paleotethys. There is also a granitoid mass in the Misho Mountain (southwest of Marand), along with intermediate and acidic rocks including diorite, tonalite, monzogranite, granodiorite, and granite, which are S-type granitoids with a potassic calc-alkaline affinity, and which crop out near the Misho gabbros [Shahzeidi 2013].

3. Analytical methods

The major element compositions of minerals were acquired at the “Centre de Micro Caractérisation Raimond Castaing” (CNRS, University Toulouse III, INPT, INSA, Toulouse, France), using a Cameca SXFive electron microprobe. The operating conditions were as follows: accelerating voltage 15 kV; beam current 20 nA; analysed surface around 2 × 2 μm2. The following standards were used: albite (Na), periclase (Mg), corundum (Al), sanidine (K), wollastonite (Ca, Si), pyrophanite (Mn), hematite (Fe), Cr2O3 (Cr), NiO (Ni) and sphalerite (Zn).

The bulk rock major and minor elements were analyzed using an Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer (ICP-AES) Horiba Jobin Yvon Ultima 2 at the “Pôle de Spectrométrie Océan” (PSO/IUEM, Plouzané, France), following the protocol adapted from Cotten et al. [1995]. Each powdered sample was digested in Teflon vials with HF 32N and HNO3 14.4N and the dry residue was dissolved in a H3BO3 solution. WSE and ACE international standards were used as internal and external control. The precision of measurements performed on that instrument is usually better than 1% for both SiO2 and TiO2, 2% for Al2O3 and Fe2O3, and better than 4% for the other major oxides.

Trace element concentrations were determined using a High Resolution Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (HR ICP-MS) Thermo Finnigan Element II (“Pôle de Spectrométrie Océan” PSO/IUEM, Plouzané, France), following a method adapted from Barrat et al. [2007]. About 100 mg of sample were digested in Teflon vials within distilled HF 32N and HNO3 14.4N. The dry residue was dissolved in HNO3 14.4N and then in HCl 3N. An aliquot of the solution was diluted in HNO3 0.3N and spiked with Tm spike. BCR2 and BEN were used as external control and BHVO-2 was used for internal control. The precision of measurements was better than 5% for all elements.

Samples were also analyzed for Sr and Nd radiogenic isotopes. About 200 mg of sample material was weighed and dissolved in Savillex beakers in a mixture of ultrapure distilled HF (24N), and HNO3 (14N) for four days at 120 °C on a hot plate. Sr and Nd fractions were chemically separated using the Eichrom specific resins TRU-spec, Sr-spec and Ln-spec following conventional column chemistry procedure [Pin and Santos Zalduegui 1997]. The Sr and Nd isotope compositions were measured in static mode on a Thermo TRITON spectrometer at the PSO (IUEM, Plouzané, France). All measured Sr and Nd ratios were normalized to 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194 and 146Nd/144Nd = 0.7219, respectively and 87Sr/86Sr values were normalized to the recommended value of NBS987 (0.710250). During the course of analysis, Nd standard solution La Jolla gave 0.511859 ± 2 (n = 2, recommended value 0.511850) and JNdi gave 0.512117 ± 3 (n = 1, recommended value 0.512100).

4. Petrography

4.1. Host volcanic rocks

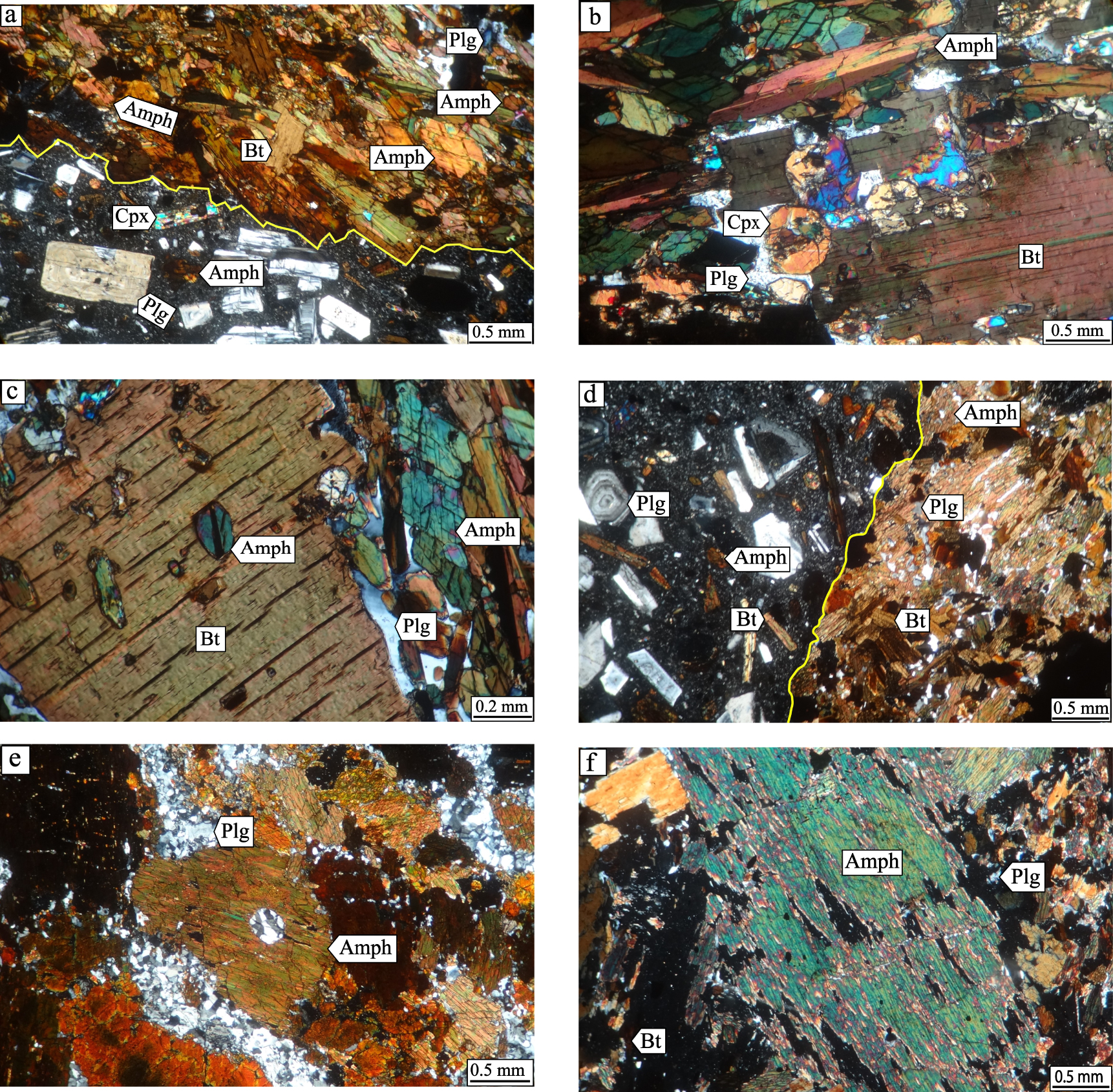

The volcanic series of the study area consists of SiO2-undersaturated rocks (e.g., leucitite, leucite–basanite, leucite–tephrite, basanite, and tephrite) to SiO2-saturated rocks such as trachyandesite, andesite, trachydacite, and dacite. The hornblendite xenoliths occur within the trachyandesite rocks. These rocks show microlitic porphyritic (Figure 3a) or porphyritic (Figure 3d) textures.

Photomicrographs of host volcanic rocks and hornblendite xenoliths from the study area: (a) plagioclase (Plg), clinopyroxene (Cpx), amphibole (Amph) and biotite (Bt) phenocrysts in trachyandesite and hornblendite with amphibole and biotite as cumulus phases and plagioclase as intercumulus phase (crossed polars: XPl). (b) Hornblendite with amphibole, clinopyroxene and biotite as cumulus phases and plagioclase as intercumulus phase, XPl. (c) Hornblendite with amphibole and biotite as cumulus phases and plagioclase as intercumulus phase, XPl. (d) Plagioclase, amphibole and biotite phenocrysts in trachyandesite and hornblendite with amphibole and biotite as cumulus phases and plagioclase as intercumulus phase, XPl. (e) Hornblendite with amphibole (as cumulus phase) and plagioclase as intercumulus phase, XPl. (f) Hornblendite with amphibole and biotite as cumulus phases and plagioclase as intercumulus phase, XPl. Group 1 xenolith: a–c. Group 2 xenolith: d–f.

Andesine plagioclase is the most abundant mineral phase in these volcanic rocks, making 45–50% of total modal content. The size of this mineral varies from very fine microliths (less than 0.1 mm) occurring within the matrix, to phenocrysts up to 1.2 mm in size. In some cases, the variation in size is transitional, resulting in a seriate texture (Figure 3a). Most of the plagioclases display Carlsbad and polysynthetic twins and some of them display a sieve texture (Figure 3a) or even zoning (Figures 3a, d). Clinopyroxene constitutes 8–10% of the samples. This mineral is observed as phenocryst in the investigated rocks but not as microlite in the matrix. It is euhedral to subhedral and ranges in size from 0.2 to 1.5 mm. The minor mineral phases of these rocks include amphibole, biotite, K-feldspar, apatite, and opaque minerals associated to glass in some samples. Euhedral and subhedral brown hornblende ranging in size from 0.2 to 1 mm is also observed, amounting up to 4–5% of the modal content of samples, some crystals displaying opacitization (Figure 3a). Another minor mineral is biotite, which makes up to 4–6% of the mode. The size of this mineral ranges from 0.3 to 0.8 mm, and some biotites also display opacitization (Figure 3d). Apatite and opaque minerals smaller than 0.5 mm (1–2% of the mode) commonly occur.

4.2. Hornblendite xenoliths

Hornblendite xenoliths are elliptic black lustrous rock pieces with dimensions of 3 × 10 cm. Based on the occurrence or absence of clinopyroxene and the plagioclase modal content, these xenoliths are divided into two groups: Group 1 with clinopyroxene and always less than 10% of plagioclase and Group 2 lacking clinopyroxene and with commonly more than 10% of plagioclase.

4.2.1. Group 1

Amphibole constitutes 65–80% of the modal content of hornblendites from this group. Biotite and plagioclase are the two other main mineral phases with modal content ranging from 5 to 25% and from 5 to 10%, respectively (Table 7). These rocks are characterized by adcumulus texture with 0.2–0.35 mm subhedral to euhedral brown amphibole as the main cumulus phase (Figures 3a–c). In some amphiboles of this group, a slight color change is seen from the mantle to the rim, so that the color of the rim looks darker than the mantle (Figure 3a). Euhedral and subhedral biotites ranging from 0.5 to 3 mm in size also occur as cumulus phases in these samples. Biotite in this group is more abundant than in Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks. Some samples locally show a poikilitic texture, characterized by tiny opaques and amphiboles included within biotite crystals (Figure 3c). Small anhedral plagioclases constitute the intercumulus phase. Clinopyroxene, opaque, and apatite are minor minerals in Group 1 samples. Clinopyroxene mostly occurs as subhedral crystals less than 1 mm in size (Figure 3b).

4.2.2. Group 2

Group 2 hornblendites display orthocumulus texture (Figures 3d–f) with amphibole (55–95%), plagioclase (3–25%), and biotite (3–12%) as the main mineral phases (Table 7). Similar to the Group 1 xenoliths, amphibole and biotite are the cumulus phases while plagioclase is the intercumulus phase. Amphiboles in this group are euhedral and subhedral and range from 0.2 to 5.5 mm. Amphiboles are more abundant in this group compared to the Group 1 xenoliths and host volcanic rocks, and show no distinct orientation (Figures 3d–f). Biotites are mainly subhedral and 0.5–3 mm in size and are less abundant compared to Group 1. Moreover, 0.2–1 mm large anhedral plagioclases occur in the interstices of these mafic minerals. Unlike the Group 1 xenoliths and host volcanic rocks, this group does not contain clinopyroxene. Opaque minerals and apatite less than 1 mm in size are observed as minor minerals in this group. They are less abundant than in Group 1 hornblendites.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Mineral chemistry

Four samples were analyzed using the electron microprobe technique (two samples from Group 1, one from Group 2 and one from host volcanic). For samples k (v-k), k-6 (v-k-6) and k-8 (v-k-8), the constituent minerals of the host volcanic rock (v-k, v-k-6 and v-k-8) and xenoliths (k, k-6 and k-8) were analyzed, while for sample v-k-20 only the constituent minerals of the host volcanic rock were analyzed.

5.1.1. Clinopyroxene

As mentioned above, Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths lack clinopyroxene and thus for comparison, some clinopyroxene of the host volcanic rocks and Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths are presented, in order to determine differences or similarities of composition, magmatic series and conditions of formation of this mineral in the studied samples.

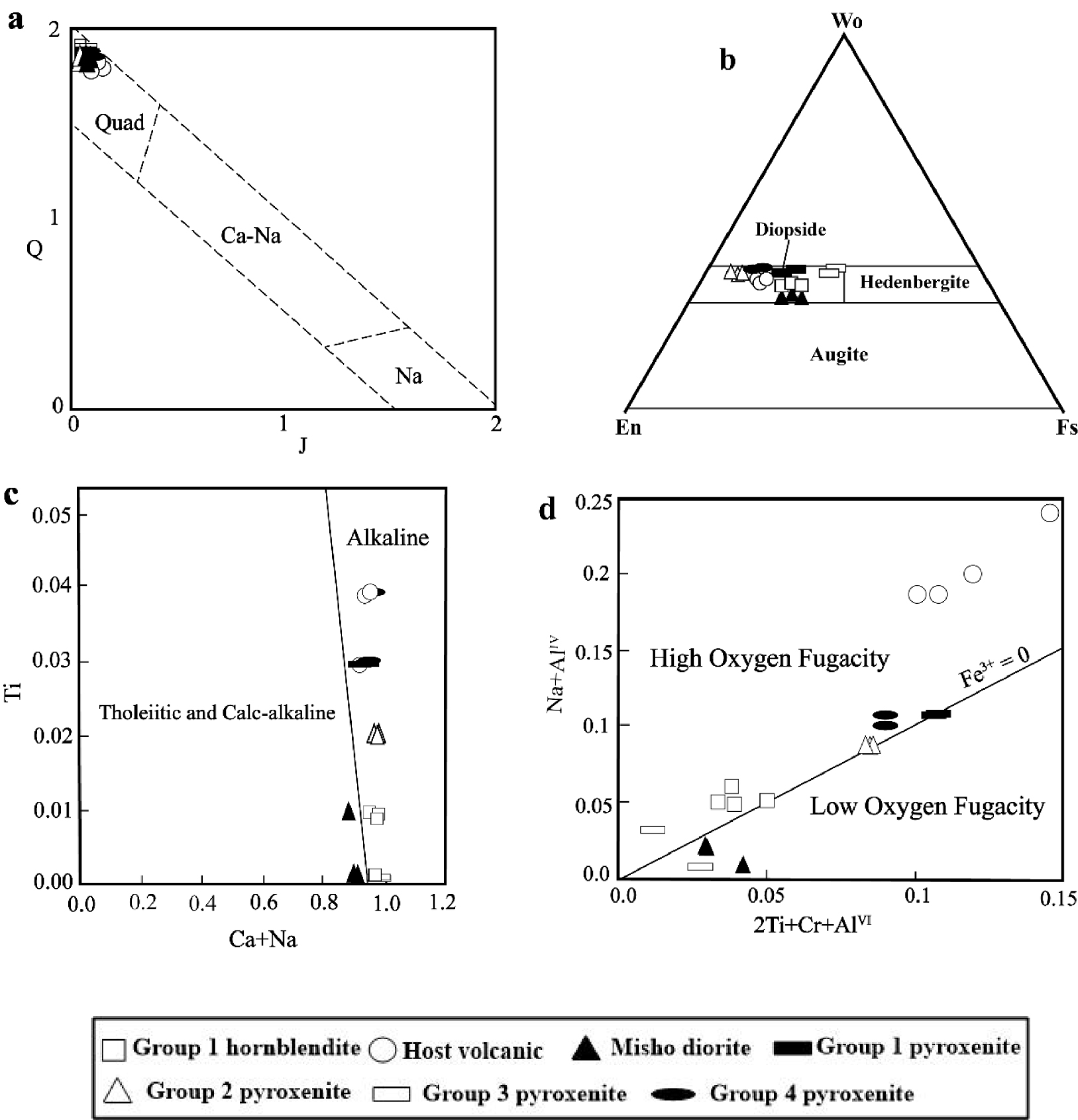

The composition of clinopyroxenes in Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks plot in the field of Quad (Ca-pyroxene) in the Q–J diagram of Morimoto and Kitamura [1983] (Figure 4a). All the investigated clinopyroxenes are diopsides (Figure 4b).

(a) Composition of clinopyroxenes in the Q–J diagram (J = 2Na, Q = Ca+Mg+Fe2+) [Morimoto and Kitamura 1983]. (b) Classification of clinopyroxenes [Morimoto et al. 1988]. (c) Plot of Ti versus Na+Ca for clinopyroxenes from the volcanic rocks and Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths [Leterrier et al. 1982]. (d) Plot of Na+AlIV versus 2Ti+Cr+AlVI for clinopyroxenes from the samples [Schweitzer et al. 1979].

The composition of clinopyroxenes can provide valuable information about the magmas from which they crystallized [Zhang et al. 2018]. The Ti versus Ca+Na diagram [Leterrier et al. 1982] indeed shows that clinopyroxenes from host volcanic rocks lie in the alkaline field and clinopyroxenes from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths lie in the alkaline field and close to the dividing line (Figure 4c). The position of all investigated clinopyroxenes of host volcanic rocks in the Na+AlIV versus Cr+2Ti+AlVI diagram [Schweitzer et al. 1979] indicates that they crystallized at high oxygen fugacity conditions (Figure 4d). The clinopyroxenes of Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths in this diagram plot also in the high oxygen fugacity field, close to the dividing line, with a sample plotting on the dividing line. The Mg/Mg+Fe2+ of clinopyroxenes from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks varies from 0.73 to 0.74 and 0.82 to 0.84, respectively (Table 1).

Mineral chemical composition of clinopyroxenes in hornblendite xenoliths, host volcanic rocks and Misho diorites

| Mineral | Clinopyroxene | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | Group 1 xenolith | Host volcanic | Misho diorite | ||||||||

| Sample | k | k | k | k | v-k | v-k | v-k | v-k | A2-43 | A2-43 | A2-43 |

| Location | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core |

| SiO2 | 52.57 | 52.93 | 52.83 | 52.75 | 49.44 | 49.21 | 46.85 | 48.54 | 54.02 | 53.86 | 54.34 |

| TiO2 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 1.21 | 1.23 | 1.28 | 1.27 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| Al2O3 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 3.83 | 3.84 | 6.21 | 3.99 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.72 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| FeO(t) | 8.59 | 8.77 | 9.40 | 8.92 | 7.94 | 8.75 | 9.13 | 8.33 | 10.74 | 10.65 | 10.18 |

| MnO | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| MgO | 13.07 | 12.88 | 12.67 | 12.95 | 13.18 | 12.71 | 11.75 | 12.72 | 13.61 | 13.65 | 13.05 |

| CaO | 22.80 | 22.75 | 23.28 | 22.94 | 22.39 | 22.42 | 22.65 | 22.23 | 21.58 | 21.75 | 22.42 |

| Na2O | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| K2O | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Total | 99.25 | 99.66 | 100.69 | 100.01 | 99.08 | 99.21 | 98.89 | 98.23 | 101.10 | 101.19 | 101.30 |

| Cations calculated on the basis of 6 oxygens | |||||||||||

| Si | 1.98 | 1.99 | 1.97 | 1.98 | 1.87 | 1.87 | 1.79 | 1.86 | 2.00 | 1.99 | 2.01 |

| AlIV | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| AlVI | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Fe3+ | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cr | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ti | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Fe2+ | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| Mn | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Mg | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.72 |

| Ca | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.89 |

| Na | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| K | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 4.01 | 4.00 | 4.01 | 4.01 | 4.03 | 4.04 | 4.05 | 4.04 | 3.99 | 3.99 | 3.98 |

| mg# | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.69 |

| Wo | 47.26 | 47.32 | 47.70 | 47.33 | 47.41 | 47.52 | 48.90 | 47.62 | 43.98 | 44.17 | 45.97 |

| En | 37.71 | 37.28 | 36.12 | 37.18 | 38.83 | 37.49 | 35.30 | 37.91 | 38.59 | 38.58 | 37.23 |

| Fs | 15.02 | 15.40 | 16.18 | 15.49 | 13.76 | 14.99 | 15.81 | 14.47 | 17.43 | 17.25 | 16.80 |

Misho data are from Shahzeidi [2013].

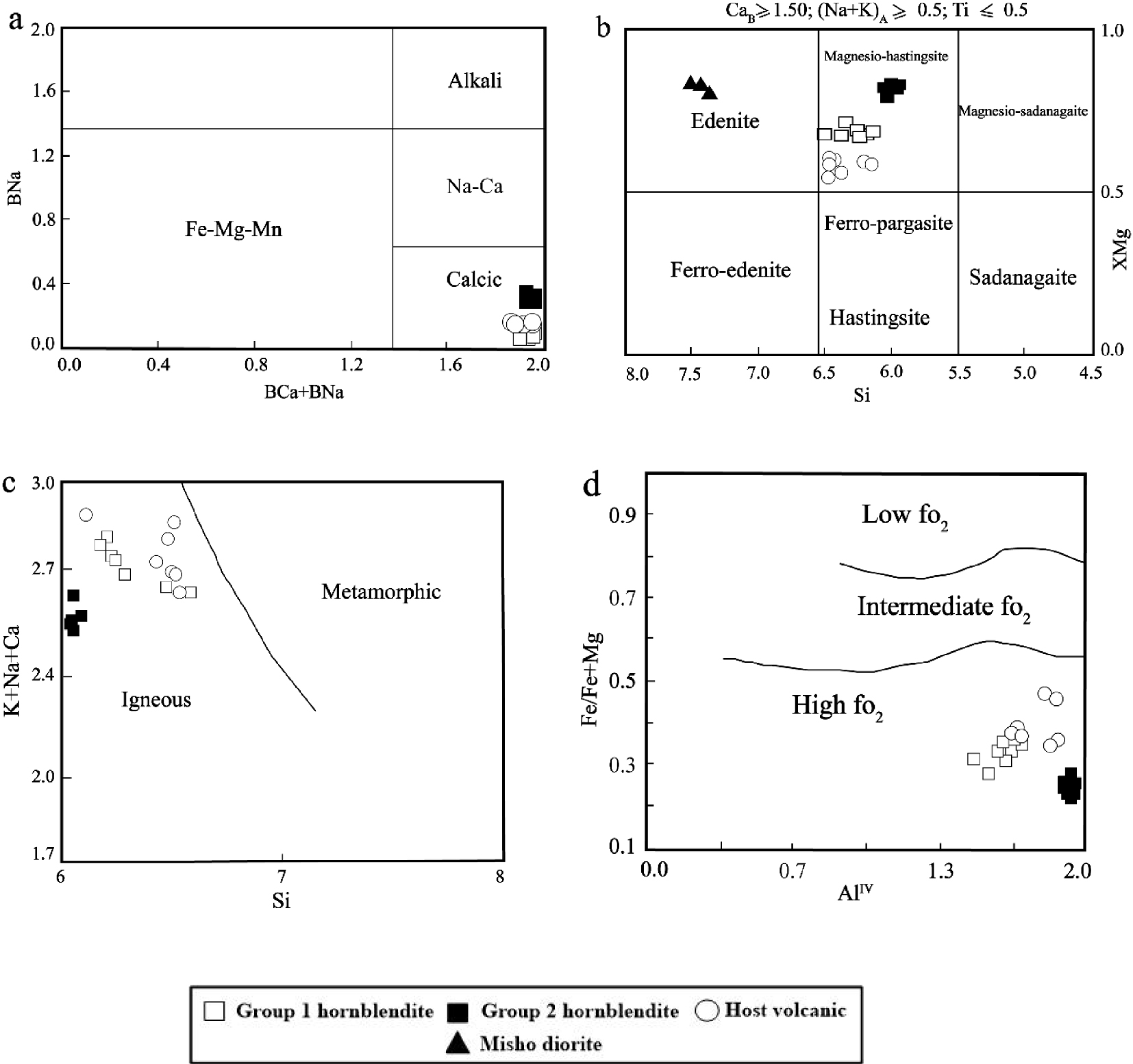

(a) Composition of amphiboles in the BCa+BNa versus BNa diagram [Leake et al. 1997]. (b) Classification of amphiboles [Leake et al. 1997]. (c) Plot of Si versus K+Na+Ca for amphiboles from the investigated samples [Sial et al. 1998]. (d) Plot of AlIV versus Fe/Fe+Mg for amphiboles from the host volcanic rocks and hornblendite xenoliths [Anderson and Smith 1995].

Figure 4b illustrates the compositional difference between clinopyroxenes from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths and those from volcanic rocks. Clinopyroxenes from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths indeed display higher SiO2 and MnO contents and lower Al2O3, TiO2, and Na2O contents than those of clinopyroxene from their host volcanic rocks. In order to compare the composition of clinopyroxenes from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths with groups 1, 2, 3 and 4 of pyroxenite xenoliths from study area [Khezerlou et al. 2017], representative analyses of the latter are given in Figures 4a–d. As can be seen in these figures, the compositions of the clinopyroxenes from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths differ from those of clinopyroxenes from pyroxenite xenoliths of the study area. They are different in most of the major elements such as SiO2, Na2O, MgO, FeO(t), MnO, and Al2O3 (Table 1). We also compared the clinopyroxenes from the xenoliths with those from the Misho diorites, located near the study area [Shahzeidi 2013]. In both cases the clinopyroxenes are diopsides (Figure 4b) but those from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths contain more Al2O3, CaO, MnO, and Na2O and less SiO2 and FeO compared to those from the Misho diorites (Table 1). As can be seen in Figures 4c and d, the composition of the clinopyroxenes from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths differs from those of clinopyroxenes from the Misho diorites.

5.1.2. Amphibole

As shown in Figure 5a, the amphiboles from all the investigated xenoliths (Group 1 and Group 2) as well as amphiboles from host volcanic rocks are calcic amphiboles as illustrated by the BNa versus BNa+BCa diagram of Leake et al. [1997]. More precisely, according to Mg/Mg+Fe2+ versus Si diagram [Leake et al. 1997], amphiboles from Group 1 xenoliths and host volcanic rocks are magnesiohastingsites while those from Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths are pargasites (Figure 5b). In the K+Na+Ca versus Si diagram [Sial et al. 1998], amphiboles from the two groups of hornblendite xenoliths plot within the magmatic (igneous) amphiboles field (Figure 5c).

The Mg/Mg+Fe2+ ratio of amphibole from Group 1 and Group 2 xenoliths and host volcanic rocks vary from 0.67 to 0.72, 0.79 to 0.85, and 0.54 to 0.67, respectively (Table 2). In the AlIV versus Fe2+/Fe2++Mg diagram [Anderson and Smith 1995], amphiboles from the xenoliths and host volcanic rocks fall within the high-oxygen fugacity field (Figure 5d). The core, mantle and rim of amphiboles from Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths do not show considerable and systematic change in composition. Yet, in some of amphiboles of Group 1, FeO(t), CaO and MnO increase from the mantle to the rim (Table 2).

Mineral chemical composition and P–T estimate of amphiboles in hornblendite xenoliths, host volcanic rocks and Misho diorites

| Mineral | Amphibole | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | Group 1 xenolith | Misho diorite | |||||||||

| Sample | k | k | k | k-6 | k-6 | k-6 | k-6 | k-6 | A2-43 | A2-43 | A2-43 |

| Location | Core | Core | Core | Rim 1 | Mantle 1 | Core | Mantle 2 | Rim 2 | Core | Core | Core |

| SiO2 | 43.52 | 43.21 | 43.31 | 42.74 | 42.63 | 42.11 | 42.00 | 42.08 | 52.57 | 53.61 | 52.89 |

| TiO2 | 1.82 | 2.15 | 2.07 | 2.13 | 2.16 | 2.24 | 2.26 | 2.18 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.23 |

| Al2O3 | 10.68 | 11.75 | 11.78 | 12.26 | 12.26 | 12.56 | 12.57 | 12.39 | 3.54 | 3.51 | 3.78 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| FeO(t) | 12.27 | 12.72 | 11.82 | 12.98 | 12.71 | 12.74 | 12.82 | 13.36 | 15.30 | 14.48 | 15.80 |

| MnO | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.32 |

| MgO | 12.68 | 12.48 | 13.40 | 12.81 | 12.71 | 12.53 | 12.63 | 12.40 | 14.57 | 15.49 | 14.57 |

| CaO | 11.47 | 11.67 | 11.76 | 12.08 | 11.78 | 11.81 | 11.98 | 11.99 | 10.92 | 10.75 | 10.27 |

| Na2O | 1.99 | 2.20 | 2.23 | 2.32 | 2.17 | 2.24 | 2.23 | 2.22 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.42 |

| K2O | 1.08 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.10 | 1.13 | 1.16 | 1.24 | 1.16 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.22 |

| Total | 95.64 | 97.46 | 97.47 | 98.63 | 97.65 | 97.53 | 97.84 | 98.00 | 97.94 | 98.48 | 98.53 |

| Cations calculated on the basis of 23 oxygens | |||||||||||

| Si | 6.52 | 6.37 | 6.35 | 6.25 | 6.27 | 6.22 | 6.19 | 6.21 | 7.46 | 7.49 | 7.41 |

| AlIV | 1.48 | 1.63 | 1.65 | 1.75 | 1.73 | 1.78 | 1.81 | 1.79 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.59 |

| Sum T | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| AlVI | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Ti | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Cr | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fe3+ | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 1.26 |

| Fe2+ | 1.34 | 1.35 | 1.13 | 1.31 | 1.26 | 1.29 | 1.31 | 1.34 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 0.59 |

| Mn | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Mg | 2.83 | 2.74 | 2.93 | 2.79 | 2.79 | 2.76 | 2.78 | 2.73 | 3.08 | 3.23 | 3.04 |

| Sum C | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Ca | 1.84 | 1.84 | 1.85 | 1.89 | 1.86 | 1.87 | 1.89 | 1.89 | 1.66 | 1.61 | 1.54 |

| Na | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Sum B | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.75 | 1.68 | 1.66 |

| Na | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| K | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Sum A | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| mg# | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| KD | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | |||

| P (Kb) | 5.6 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 6.9 | |||

| T (°C) | 888 | 913 | 923 | 930 | 925 | 936 | 938 | 930 | |||

Misho data are from Shahzeidi [2013].

(continued)

| Mineral | Amphibole | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | Group 2 xenolith | Host volcanic | ||||||||||

| Sample | k-8 | v-k-20 | v-k-8 | v-k | ||||||||

| Location | Rim 1 | Mantle 1 | Core | Mantle 2 | Rim 2 | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core |

| SiO2 | 41.43 | 41.47 | 41.21 | 41.68 | 41.25 | 43/22 | 43/43 | 43/31 | 41.07 | 41.84 | 41.64 | 41.47 |

| TiO2 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 1/81 | 1/88 | 1/91 | 2.66 | 2.23 | 2.23 | 2.34 |

| Al2O3 | 15.85 | 16.03 | 16.61 | 15.56 | 15.82 | 9/12 | 9/08 | 9/02 | 12.02 | 11.31 | 10.48 | 10.91 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| FeO(t) | 11.54 | 11.41 | 11.57 | 11.72 | 11.71 | 16/98 | 16/92 | 16/78 | 13.70 | 12.81 | 18.26 | 18.01 |

| MnO | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0/46 | 0/51 | 0/52 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.55 |

| MgO | 12.64 | 12.64 | 12.32 | 12.64 | 12.42 | 11/4 | 11/23 | 11/42 | 12.09 | 12.57 | 9.64 | 9.92 |

| CaO | 10.51 | 10.56 | 10.71 | 10.62 | 10.75 | 11/12 | 11/21 | 11/02 | 11.57 | 11.78 | 11.05 | 11.36 |

| Na2O | 2.97 | 3.02 | 2.90 | 2.98 | 2.92 | 2/14 | 2/06 | 2/01 | 2.58 | 2.12 | 1.99 | 2.09 |

| K2O | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.57 | 1/43 | 1/35 | 1/32 | 1.19 | 1.53 | 1.70 | 1.69 |

| Total | 96.24 | 96.43 | 96.73 | 96.61 | 96.56 | 97.70 | 97.70 | 97.34 | 97.12 | 96.50 | 97.51 | 98.34 |

| Cations calculated on the basis of 23 oxygens | ||||||||||||

| Si | 6.02 | 6.02 | 5.97 | 6.05 | 6.02 | 6/46 | 6/50 | 6/48 | 6.14 | 6.28 | 6.31 | 6.24 |

| AlIV | 1.98 | 1.98 | 2.03 | 1.95 | 1.98 | 1/54 | 1/50 | 1/52 | 1.86 | 1.72 | 1.69 | 1.76 |

| Sum T | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| AlVI | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0/07 | 0/10 | 0/07 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| Ti | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0/20 | 0/21 | 0/21 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| Cr | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0/01 | 0/01 | 0/01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fe3+ | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0/60 | 0/53 | 0/65 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.49 | 0.46 |

| Fe2+ | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 1/52 | 1/59 | 1/45 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.82 | 1.80 |

| Mn | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0/06 | 0/06 | 0/07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Mg | 2.74 | 2.74 | 2.66 | 2.74 | 2.70 | 2/54 | 2/50 | 2/55 | 2.69 | 2.81 | 2.18 | 2.23 |

| Sum C | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Ca | 1.64 | 1.64 | 1.66 | 1.65 | 1.68 | 1/78 | 1/80 | 1/77 | 1.85 | 1.90 | 1.79 | 1.83 |

| Na | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0/22 | 0/20 | 0/23 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| Sum B | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Na | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0/40 | 0/39 | 0/35 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| K | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0/27 | 0/26 | 0/25 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| Sum A | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0/67 | 0/65 | 0/60 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.76 |

| mg# | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0/63 | 0/61 | 0/64 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| KD | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0/28 | 0/28 | 0/27 | ||||

| P (Kb) | 9.8 | 9.9 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 5.9 | ||||

| T (°C) | 964 | 968 | 971 | 960 | 965 | 850 | 846 | 846 | ||||

As shown in Figure 5b, the amphiboles of the host volcanic rock and those of the two groups of hornblendite xenoliths display some compositional differences; for instance, amphiboles from Group 1 and Group 2 xenoliths show higher MgO and Mg/Mg+Fe2+ values and lower FeO(t), K2O, and MnO (and also Al2O3 for Group 2) contents than those of their equivalent in host volcanic rocks. Furthermore, some differences also occur between amphiboles from the two groups of hornblendite xenoliths; for instance, amphiboles from Group 1 have slightly higher TiO2, Na2O, MgO, and CaO contents and a lower Al2O3 content than amphibole from Group 2 (Table 2). The composition of amphiboles between different samples (k, k-6) in Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths is not homogeneous and there is a slight difference in the content of some of the major elements (for example, SiO2, Al2O3, K2O) (Table 2).

We also compared the amphiboles of the two investigated groups of hornblendite xenoliths with those of the Misho diorites [Shahzeidi 2013]. Amphiboles in the Misho diorites are edenites (Figure 5b), and are different from those from the investigated hornblendite xenoliths in terms of major elements such as SiO2, TiO2, Na2O, MgO, K2O, FeO(t), MnO, and Al2O3 (Table 2).

5.1.3. Feldspar

According to the classification of Deer et al. [1966], the composition of plagioclases in Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths is andesine and labradorite, respectively. On the other hand, the composition of feldspars of their host volcanic rocks are oligoclase, andesine and sanidine (Figure 6). Zoning occurs in some volcanic plagioclase phenocrysts, with SiO2, Na2O, and K2O contents increasing from rim to core while CaO and Al2O3 contents decrease (normal zoning) (Table 3).

Classification of plagioclases from the host volcanic rocks and hornblendite xenoliths [Deer et al. 1966].

Mineral chemical composition of feldspars in hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks

| Mineral | Feldspar | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | Group 1 xenolith | Group 2 xenolith | Host volcanic | ||||||||||

| Sample | k | k | k-6 | k-6 | k-8 | k-8 | k-8 | v-k | v-k | v-k | v-k | v-k | v-k-6 |

| Location | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Rim 1 | Mantle 1 | Core 1 | Mantle 2 | Rim 2 | Core |

| SiO2 | 60.58 | 60.37 | 59.00 | 59.37 | 51.51 | 51.12 | 51.38 | 60.83 | 60.44 | 58.53 | 60.21 | 62.35 | 71.41 |

| TiO2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| Al2O3 | 24.56 | 24.42 | 25.77 | 24.68 | 30.94 | 30.20 | 30.88 | 24.06 | 25.05 | 26.39 | 25.17 | 23.73 | 15.13 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| FeO(t) | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 1.18 |

| MnO | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| MgO | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| CaO | 6.92 | 6.88 | 8.30 | 7.36 | 13.87 | 13.92 | 13.94 | 6.04 | 6.86 | 8.63 | 7.15 | 5.48 | 1.36 |

| Na2O | 7.07 | 7.17 | 6.25 | 6.92 | 3.44 | 3.35 | 3.28 | 7.32 | 7.18 | 6.39 | 6.85 | 7.61 | 2.19 |

| K2O | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 1.04 | 5.87 |

| Total | 100.07 | 99.75 | 100.44 | 99.32 | 100.24 | 99.14 | 100.07 | 99.38 | 100.58 | 100.76 | 100.64 | 100.52 | 97.53 |

| Cations calculated on the basis of 8 oxygens | |||||||||||||

| Si | 2.42 | 2.42 | 2.35 | 2.39 | 2.06 | 2.06 | 2.05 | 2.45 | 2.40 | 2.32 | 2.39 | 2.48 | 2.93 |

| Al | 1.31 | 1.31 | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.65 | 1.62 | 1.65 | 1.29 | 1.33 | 1.40 | 1.33 | 1.26 | 0.83 |

| Ti | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Fe | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Mn | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Zn | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ca | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 1.11 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.11 |

| Na | 1.13 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 1.15 | 1.14 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 1.21 | 0.36 |

| K | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.96 |

| Total | 5.55 | 5.56 | 5.52 | 5.56 | 5.40 | 5.41 | 5.39 | 5.55 | 5.56 | 5.53 | 5.55 | 5.58 | 5.32 |

| Or | 6.71 | 6.41 | 6.01 | 6.10 | 1.14 | 1.43 | 1.35 | 8.04 | 6.70 | 5.26 | 7.17 | 9.11 | 67.19 |

| Ab | 62.61 | 63.25 | 56.48 | 61.30 | 32.74 | 32.03 | 31.57 | 64.67 | 63.13 | 56.54 | 61.01 | 66.82 | 25.04 |

| An | 30.68 | 30.34 | 37.51 | 32.61 | 66.11 | 66.54 | 67.08 | 27.29 | 30.17 | 38.21 | 31.82 | 24.08 | 7.77 |

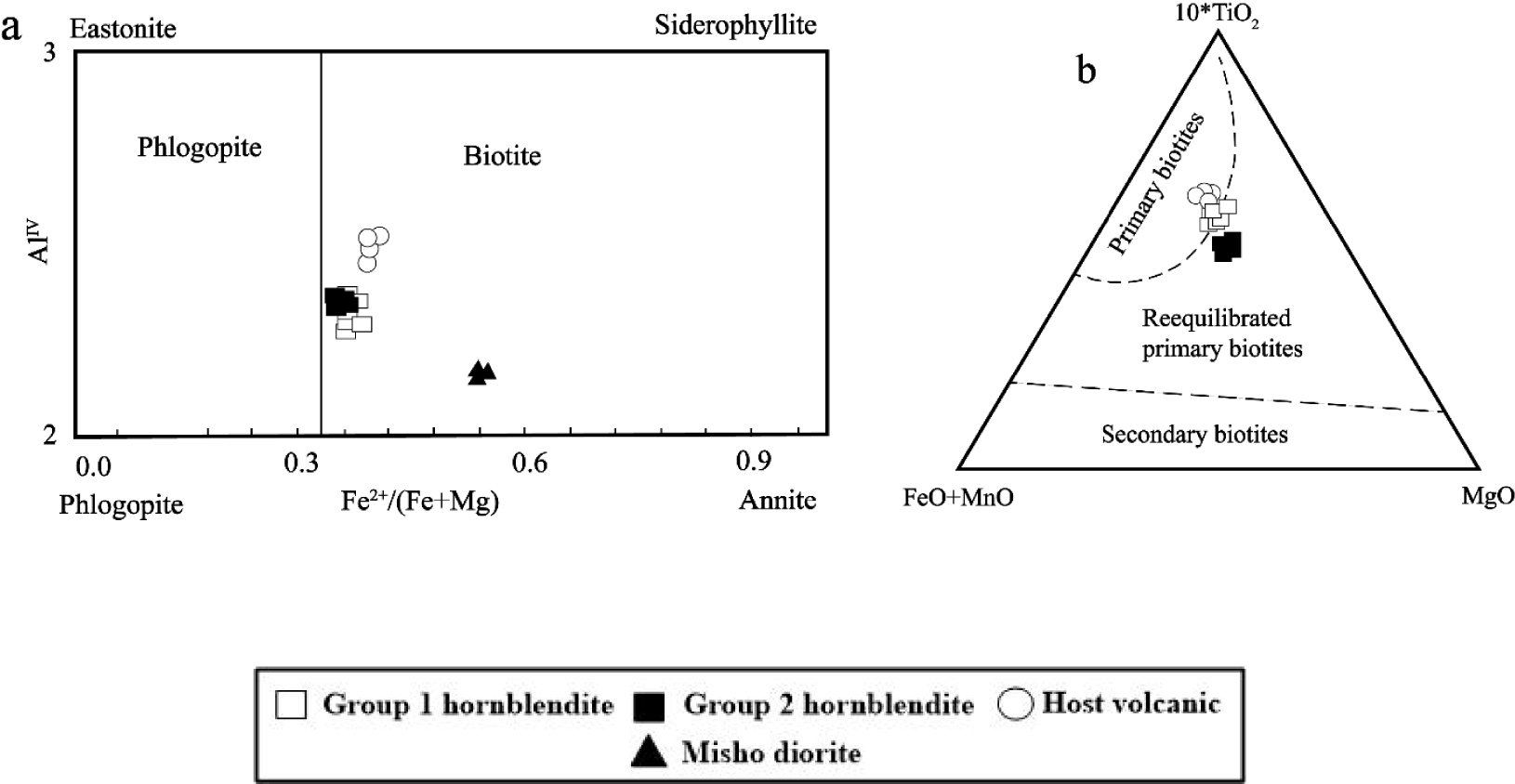

5.1.4. Biotite

According to the AlIV versus Fe2+/Fe2++Mg diagram, micas from Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks are biotites (Figure 7a) with Mg/Mg+Fe2+ values ranging from 0.62 to 0.66, 0.64 to 0.65 and 0.60 to 0.61, respectively (Table 4).

(a) Classification of micas [Speer 1984]. (b) Composition of biotites in the 10∗TiO2–FeO–MgO diagram [Nachit et al. 2005].

Mineral chemical composition of biotites in hornblendite xenoliths, host volcanic rocks and Misho diorites

| Mineral | Biotite | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | Group 1 xenolith | Group 2 xenolith | |||||||||

| Sample | k | k-6 | k-6 | k-6 | k-6 | k-6 | k-8 | k-8 | k-8 | k-8 | k-8 |

| Location | Core | Rim 1 | Mantle 1 | Core | Mantle 2 | Rim 2 | Rim 1 | Mantle 1 | Core | Mantle 2 | Rim 2 |

| SiO2 | 37.22 | 37.47 | 37.53 | 38.84 | 38.69 | 38.42 | 37.12 | 37.05 | 37.02 | 37.11 | 37.06 |

| TiO2 | 3.76 | 3.50 | 4.17 | 3.88 | 4.07 | 4.00 | 3.11 | 3.02 | 3.22 | 3.14 | 3.04 |

| Al2O3 | 14.46 | 14.29 | 14.17 | 14.96 | 14.27 | 13.90 | 14.52 | 14.61 | 14.65 | 14.55 | 14.64 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| FeO(t) | 13.71 | 14.53 | 14.68 | 12.97 | 13.91 | 14.80 | 14.13 | 14.01 | 14.06 | 14.21 | 14.08 |

| MnO | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.66 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.54 |

| MgO | 14.87 | 14.64 | 14.50 | 13.80 | 14.23 | 13.77 | 14.63 | 14.74 | 14.68 | 14.55 | 14.76 |

| CaO | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Na2O | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.52 |

| K2O | 8.30 | 8.87 | 8.25 | 7.72 | 8.27 | 8.58 | 8.21 | 8.15 | 8.24 | 8.26 | 8.22 |

| Total | 92.87 | 93.89 | 93.95 | 92.73 | 94.05 | 94.12 | 93.06 | 92.99 | 92.98 | 93.05 | 92.99 |

| Cations calculated on the basis of 22 oxygens | |||||||||||

| Si | 5.64 | 5.66 | 5.65 | 5.82 | 5.77 | 5.77 | 5.65 | 5.64 | 5.63 | 5.65 | 5.64 |

| AlIV | 2.36 | 2.34 | 2.35 | 2.18 | 2.23 | 2.23 | 2.35 | 2.36 | 2.37 | 2.35 | 2.36 |

| AlVI | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| Ti | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.35 |

| Fe2+ | 1.74 | 1.83 | 1.85 | 1.62 | 1.73 | 1.86 | 1.80 | 1.78 | 1.79 | 1.80 | 1.79 |

| Mn | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Mg | 3.36 | 3.30 | 3.25 | 3.08 | 3.16 | 3.08 | 3.32 | 3.34 | 3.33 | 3.30 | 3.35 |

| Ca | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Na | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| K | 1.60 | 1.71 | 1.58 | 1.47 | 1.57 | 1.64 | 1.59 | 1.58 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.59 |

| Total | 15.48 | 15.57 | 15.45 | 15.18 | 15.34 | 15.40 | 15.57 | 15.58 | 15.56 | 15.54 | 15.58 |

| #Mg | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.65 |

(continued)

| Mineral | Biotite | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | Host volcanic | Misho diorite | |||||

| Sample | v-k-6 | v-k-20 | A2-39-3-2 | ||||

| Location | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core | Core |

| SiO2 | 36.44 | 36.39 | 36.28 | 36.22 | 37.40 | 37.30 | 37.00 |

| TiO2 | 5.04 | 5.22 | 5.02 | 5.13 | 2.90 | 2.06 | 2.25 |

| Al2O3 | 13.62 | 13.78 | 13.85 | 13.92 | 16.10 | 17.30 | 17.20 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| FeO | 15.62 | 16.17 | 16.14 | 16.08 | 21.20 | 21.90 | 21.40 |

| MnO | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.19 |

| MgO | 13.89 | 13.48 | 13.54 | 13.65 | 8.80 | 8.91 | 8.80 |

| CaO | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Na2O | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| K2O | 9.31 | 9.27 | 9.16 | 9.11 | 8.49 | 9.11 | 9.02 |

| Total | 94.86 | 95.20 | 94.97 | 95.18 | 95.47 | 96.97 | 96.07 |

| Cations calculated on the basis of 22 oxygens | |||||||

| Si | 5.52 | 5.51 | 5.50 | 5.48 | 5.96 | 5.87 | 5.87 |

| AlIV | 2.43 | 2.46 | 2.48 | 2.48 | 2.04 | 2.13 | 2.13 |

| AlVI | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 1.08 | 1.09 |

| Ti | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| Fe2+ | 1.98 | 2.05 | 2.05 | 2.03 | 2.82 | 2.88 | 2.83 |

| Mn | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Mg | 3.14 | 3.04 | 3.06 | 3.08 | 2.09 | 2.09 | 2.08 |

| Ca | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Na | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| K | 1.80 | 1.79 | 1.77 | 1.76 | 1.72 | 1.83 | 1.83 |

| Total | 15.67 | 15.64 | 15.67 | 15.67 | 16.04 | 16.18 | 16.18 |

| #Mg | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

Misho data are from Shahzeidi [2013].

The ternary diagram MgO–Fe+MnO–10TiO2 can be used to assess the origin of micas [Nachit et al. 2005] which suggests that biotites from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks are primary magmatic micas while those from Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths are recrystallized type (Figure 7b).

The biotites from Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths do not display compositional variation from core to rim (Table 4), similarly to amphiboles and plagioclases. Biotites in Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths display cores respectively higher in Al2O3, SiO2, and CaO and lower in MgO, FeO, and K2O than their rims (Table 4). The compositions of biotites from Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths are different (Figure 7a). Biotites from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths have higher SiO2 and TiO2 contents and lower MgO, MnO, and Na2O compared to micas of Group 2 (Table 4). The results show that biotites of Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths are also different from micas of their host volcanic rocks. The biotites from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths indeed have higher SiO2, MgO, CaO, and Al2O3 contents and lower FeO(t), K2O, TiO2, and Na2O contents than micas from their host volcanic rocks (Table 4). The composition of the biotites in these xenoliths is finally also different from those of Misho diorites [Shahzeidi 2013]. They indeed display higher TiO2, MgO, and Na2O and lower Al2O3, FeO(t), and K2O compared to those biotites from Misho diorites.

5.2. Whole-rock major and trace element compositions

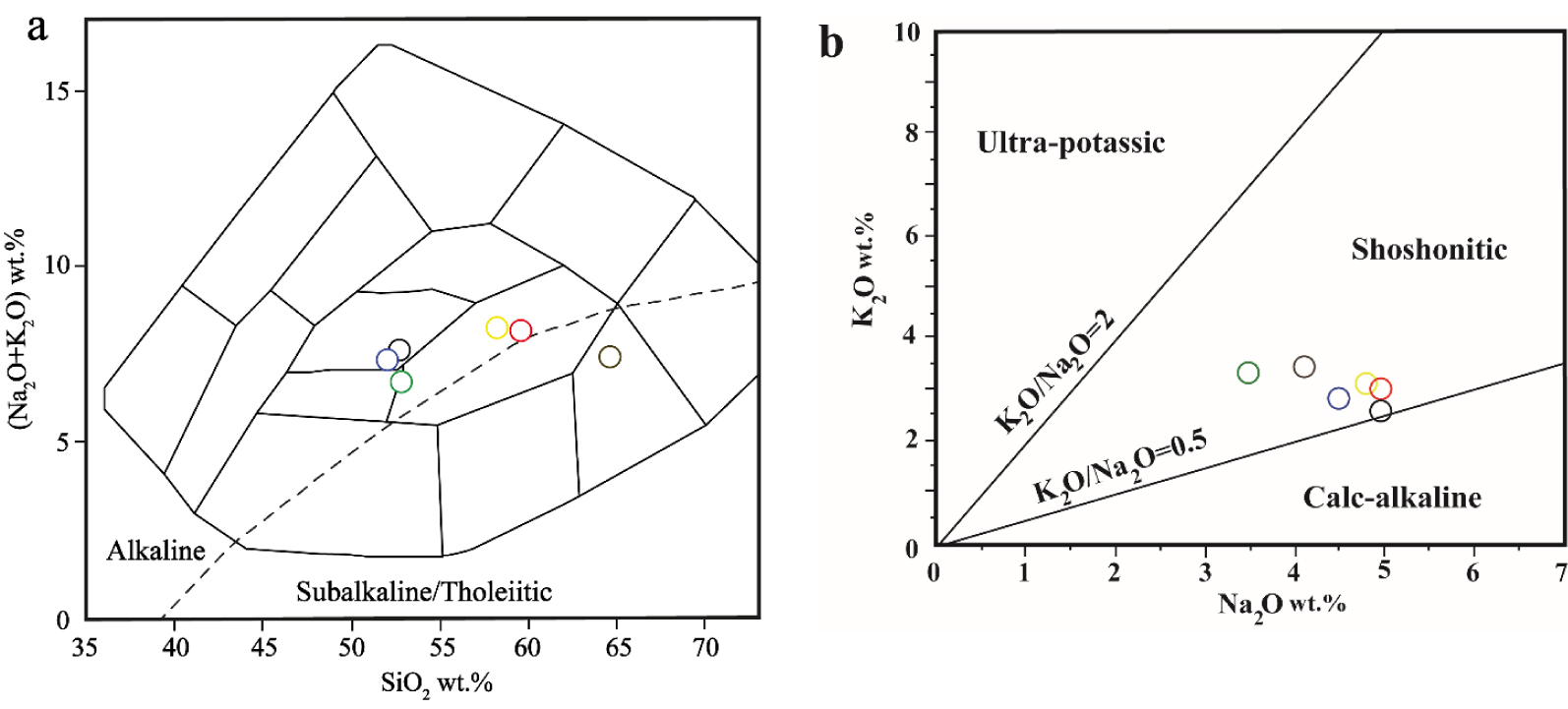

Major and trace element analyses of hornblendite xenoliths (four samples from Group 1 and three samples from Group 2) are presented in Table 5. In Figure 8a, the samples of the host volcanic rocks plot within the alkaline field (a sample plot within the subalkaline/tholeiitic field) [Cox et al. 1979] while in Figure 8b the host volcanic rocks [Khezerlou et al. 2017], fall within the shoshonite field except for a sample plotting on the line dividing the shoshonite and calc-alkaline fields. Host volcanic rocks include trachyandesites (samples v-kh-65, v-kh-52 and v-k-20) and basalt trachyandesites ( samples v-kh-87, v-kh-93 and k-26), and as mentioned, Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths are located within the trachyandesite field.

Host volcanic rocks. (a) Plotted in the TAS diagram [Cox et al. 1979]. Dashed line separates subalkaline from alkaline rocks. Most of the data plot in the alkaline field. (b) Plotted in the Na2O versus K2O diagram [after Turner et al. 1996]. The trachyandesites (host volcanics) are from Khezerlou et al. [2017]. (The blue, black, and green circles are basalt trachyandesite. The red, yellow, and brown circles are trachyandesite.)

Whole-rock major and trace element data for xenoliths and volcanic rocks

| Rock | Group 1 xenolith | Group 2 xenolith | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | K | K-6 | Kh-52 | K-11 | K-8 | Kh-12 | K-21 |

| SiO2 | 43.86 | 44.20 | 47.86 | 48.32 | 42.52 | 45.77 | 44.33 |

| TiO2 | 1.85 | 1.83 | 2.21 | 1.68 | 1.38 | 1.49 | 2.00 |

| Al2O3 | 12.39 | 12.34 | 15.10 | 16.26 | 15.33 | 15.50 | 18.29 |

| Fe2O3(t) | 12.62 | 12.26 | 14.31 | 11.67 | 12.61 | 12.00 | 12.24 |

| FeO | 7.13 | 6.93 | 7.54 | 6.16 | 7.32 | 6.54 | 6.93 |

| Fe2O3 | 4.56 | 4.44 | 5.69 | 4.65 | 4.30 | 4.55 | 4.43 |

| MnO | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| MgO | 12.11 | 11.71 | 5.42 | 7.29 | 13.03 | 7.69 | 6.66 |

| CaO | 10.40 | 10.33 | 8.44 | 10.28 | 10.42 | 9.97 | 10.19 |

| Na2O | 2.25 | 2.28 | 3.24 | 3.73 | 2.49 | 2.87 | 2.72 |

| K2O | 1.76 | 1.85 | 1.57 | 1.16 | 0.80 | 1.40 | 1.22 |

| P2O5 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.18 |

| LOI | 1.12 | 1.21 | 2.15 | 0.78 | 1.17 | 2.06 | 1.07 |

| Total | 98.82 | 98.48 | 100.80 | 101.61 | 100.22 | 99.08 | 99.07 |

| Sr | 282 | 300 | 434 | 568 | 303 | 312 | 494 |

| Ba | 356 | 361 | 541 | 592 | 127 | 137 | 261 |

| V | 383 | 380 | 308 | 299 | 242 | 263 | 267 |

| Cr | 95 | 84 | 275 | 331 | 342 | 310 | 123 |

| Co | 63 | 62 | 55 | 42 | 78 | 53 | 50 |

| Ni | 138 | 136 | 186 | 62 | 349 | 93 | 78 |

| Y | 27 | 26 | 32 | 40 | 11 | 21 | 14 |

| Zr | 57 | 57 | 81 | 58 | 28 | 47 | 54 |

| Nb | 5.9 | 6.0 | 24.5 | 9.7 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 11.1 |

| Mo | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| La | 12.5 | 10.4 | 15.4 | 17.6 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 6.4 |

| Ce | 34.8 | 27.4 | 39.1 | 38.5 | 19.0 | 16.5 | 16.3 |

| Pr | 5.0 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.7 |

| Nd | 24.5 | 19.9 | 16.7 | 19.7 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 7.5 |

| Sm | 6.4 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 1.6 |

| Eu | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Gd | 6.7 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.6 |

| Tb | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Dy | 4.9 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 1.3 |

| Ho | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Er | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.7 |

| Yb | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Lu | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Hf | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| W | 19.3 | 15.9 | 31.3 | 38.3 | 19.9 | 32.3 | 28.1 |

| Th | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| U | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Cu | 22.0 | 19.6 | 189.9 | 12.0 | 3.6 | 46.3 | 85.2 |

| Zn | 95.8 | 82.1 | 137.5 | 87.8 | 55.6 | 90.9 | 76.8 |

| Ga | 15.1 | 12.6 | 16.7 | 16.4 | 8.7 | 15.6 | 16.1 |

| Rb | 46.2 | 28.1 | 31.3 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 17.2 | 8.9 |

| Cs | 10.5 | 15.7 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 4.2 | 1.5 |

| Ta | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Pb | 5.3 | 5.1 | 8.2 | 9.7 | 2.2 | 5.6 | 4.1 |

| Ba/Nb | 60 | 60 | 22 | 61 | 16 | 19 | 23 |

| Ba/Ta | 1090 | 1409 | 446 | 1367 | 417 | 296 | 432 |

| Nb/La | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| (Ce/Yb)N | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 9.2 | 3.2 | 8.3 |

| (Dy/Yb)N | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Ce/Pb | 6.6 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 8.7 | 2.9 | 4.0 |

| #Mg | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.49 |

Major elements in wt%, trace elements and REE in ppm.

Host volcanic rocks (trachyandesites) [Khezerlou et al. 2017] contain lower FeO(t), MgO, TiO2 and CaO contents and higher SiO2, P2O5, K2O, and Na2O contents compared to those of Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths (Table 5). The Mg/Mg+Fe2+ values of Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths range from 0.42 to 0.63, and 0.49 to 0.64, respectively.

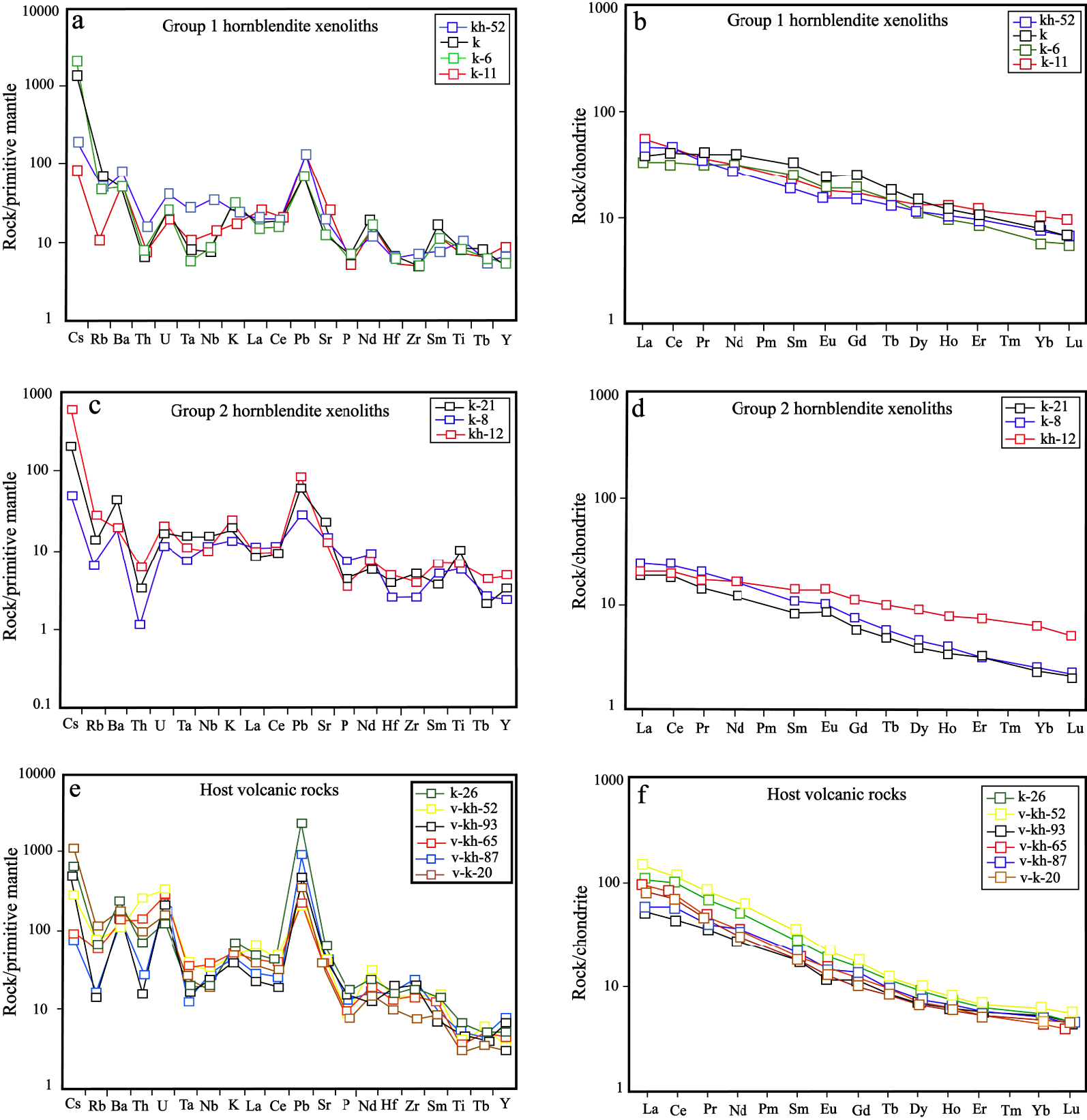

Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths are characterized by enrichment in U, Ba, Pb, Sm, Nd, Cs, Ti, and K and depletion in Th, Nb, and Zr (Figures 9a, c). The Ti, Ba, K, U, and Th contents in Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths are higher than those of Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks [Khezerlou et al. 2017] (Figures 9a, c, e). The Pb and Sr contents of host volcanic rocks [Khezerlou et al. 2017], on the other hand, are higher than those of hornblendite xenoliths. Although these xenoliths have a cumulate nature and may have lost some of their interstitial residual melt, similarly to their host volcanic rocks [Khezerlou et al. 2017], they show an enrichment in LREE compared to HREE (Figures 9b, d, f). HREE and MREE contents in Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths are higher than that in Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths. Also, LREE content in Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths is higher than that in Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths and lower than that of host volcanic rocks [Khezerlou et al. 2017]. Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths, similarly to their host volcanic rocks, are characterized by a negative Eu anomaly while Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths display a positive Eu anomaly.

(a, c, e) Primitive mantle normalized spidergrams and (b, d, f) chondrite normalized REE patterns of hornblendite xenoliths. Chondrite and primitive mantle values are from Boynton [1984] and Sun and McDonough [1989], respectively. Host volcanics data are from Khezerlou et al. [2017].

5.3. Whole-rock Sr–Nd isotopes

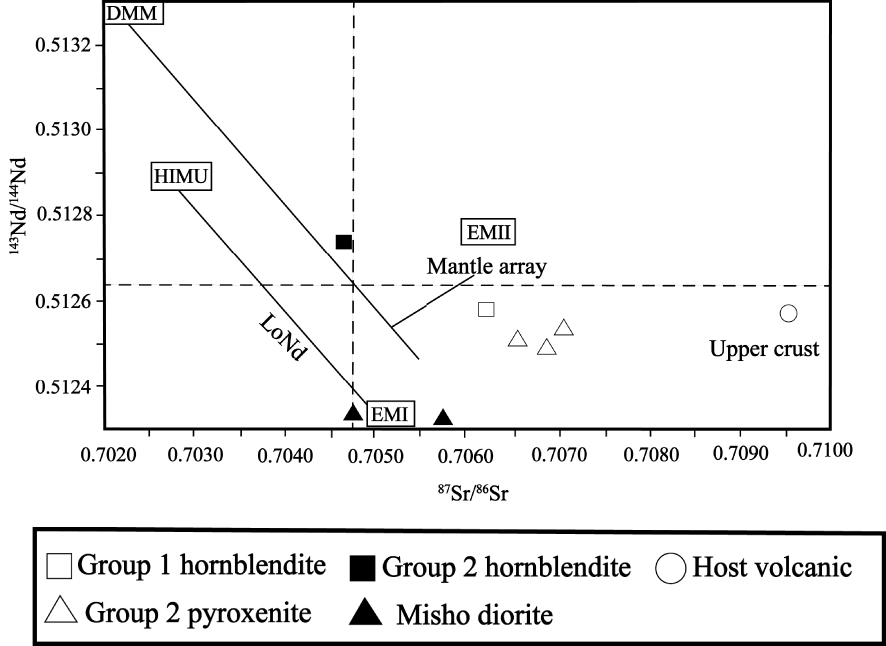

The 86Sr/87Sr and 143Nd/144Nd isotopic ratios were used to investigate and determine the origin of the investigated hornblendite xenoliths. The analyses and the sampling locations are presented in Table 6 and Figure 10, respectively. The results show that the 86Sr/87Sr ratio in Group 1 and Group 2 xenoliths are 0.706291 and 0.704685, respectively, while the 143Nd/144Nd ratio is 0.512580 and 0.512736, respectively. Samples from Group 1 xenoliths plot within EMI and EMII endmembers while those from Group 2 fall within EMII and HIMU fields. To validate the results, some host volcanic rocks and pyroxenite xenoliths [Khezerlou et al. 2017] from the study area and some Misho diorites [Shahzeidi 2013] were used (Table 6). As illustrated in Figure 10, the host volcanic rocks fall between EMII and upper crust fields (closer to the upper crust). On the other hand, Group 2 pyroxenite xenolith samples fall within EMI and EMII fields while samples from Misho diorite plot far from xenoliths and host volcanic rocks and closer to EMI endmember.

143Nd/144Nd versus 87Sr/86Sr diagram for the whole rock of investigated samples. The fields for DMM, HIMU, EMI, EMII and upper crust are from Zindler and Hart [1986]. LoNd array is from Hart et al. [1986]. Misho data are from Shahzeidi [2013] and pyroxenite xenoliths and host volcanic data are from Khezerlou et al. [2017].

Sr and Nd isotopic (whole rock) composition of xenoliths, a volcanic rock from NW Marand area and Misho diorites

| Rock | Group 1 xenolith | Group 2 xenolith | Host volcanic | Pyroxenitic xenoliths | Misho diorites | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | k-11 | kh-12 | v-kh-52 | kh-62 | kh-64 | kh14 | A2-43-1 | A2-11-1 |

| 87Sr/86Sr | 0.706291 | 0.704685 | 0.709545 | 0.707026 | 0.706825 | 0.70642 | 0.704861 | 0.705815 |

| 2𝜎 | 0.000003 | 0.000002 | 0.000002 | 0.000003 | 0.000003 | 0.000002 | 0.000013 | 0.000011 |

| 143Nd/144Nd | 0.512580 | 0.512736 | 0.512561 | 0.512525 | 0.512482 | 0.512501 | 0.512155 | 0.512010 |

| 2𝜎 | 0.000003 | 0.000002 | 0.000002 | 0.000003 | 0.000002 | 0.000002 | 0.000012 | 0.000011 |

| 𝜀Nd | −1.06 | 1.96 | −1.27 | −1.98 | −2.81 | −2.45 | −0.61 | 1.2 |

Modal compositions of xenoliths estimated by using the whole rock and constituent minerals’ major element compositions and a mixing model based on least squares method

| Rock | Sample | Clinopyroxene | Amphibole | Plagioclase | Biotite | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 xenolith | k | 1 | 81 | 8 | 10 | 100 |

| k-6 | 84 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 100 | ||

| Group 2 xenolith | k-8 | 94 | 3 | 3 | 100 |

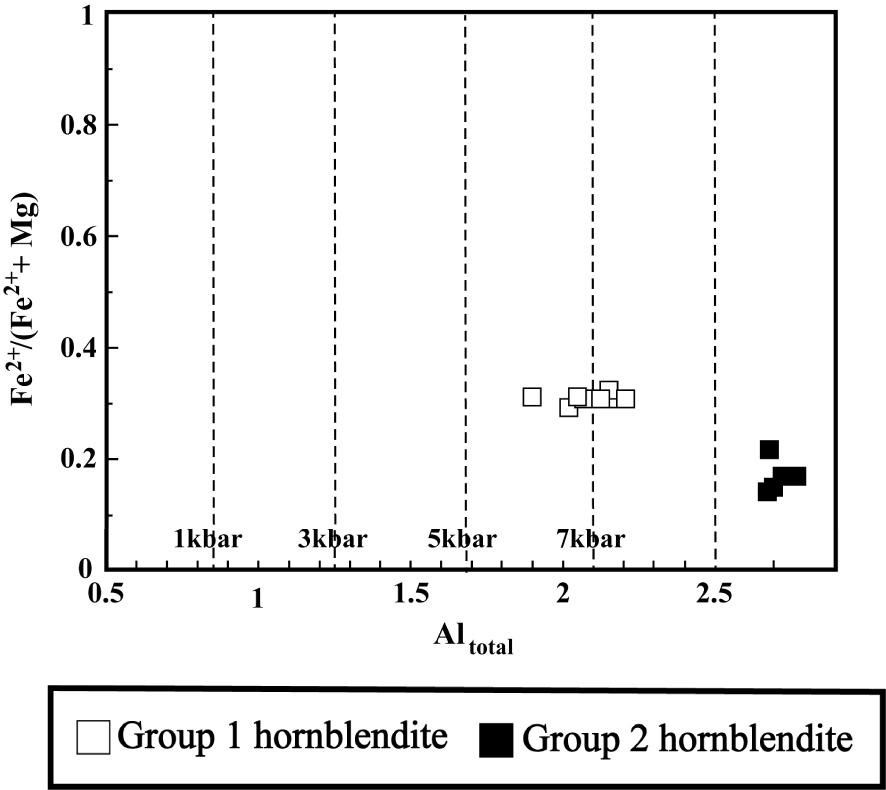

5.4. Thermobarometry

Since plagioclase in the hornblendite xenoliths occurs as the intercumulus phase and therefore formed after cumulus amphibole, the plagioclase–amphibole pairs in these samples cannot be used for thermobarometry. Therefore, only amphibole was used for this purpose. According to Putirka [2016], if KD (Fe–Mg)amph–liq is within 0.28 ± 0.11, then we may assume that the amphibole is in equilibrium with the melt. The KD from the investigated hornblendite xenoliths is not equal to 0.28 ± 0.11 (Table 2). As a result, estimate may be obtained from Hammarstrom and Zen [1968] method (P = −3.92 + 5.03 Altotal). This method independent of the temperature is solely based on the Altotal content of the amphibole. The pressure of formation of amphibole minerals from Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths using that equation ranges from 5.5 to 7 kbar and 9.5 to 10.5 kbar, respectively (Table 2). Also, according to the diagram of Altotal versus Fe/Fe+Mg, the formation pressure of amphiboles of Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths has been estimated to be more than 5.5 kbar (Figure 11). Unlike xenoliths, the KD of the investigated host volcanic rock (0.27–0.28) fall within the range 0.28 ± 0.11, the chemical composition of their amphibole and whole rock is therefore suitable to be used for barometry, as stressed above. The estimated formation pressures for amphiboles of host volcanic rock (v-k-20 sample) according to the Equation (7c) proposed by Putirka [2016] are 6–6.7 kbars.

Plot of Altotal versus Fe/Fe+Mg for amphiboles from the hornblendite xenoliths [Hammarstrom and Zen 1968].

The formation temperatures of amphibole minerals from Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rock (v-k-20 sample) estimated according to the Equation (5) {T °C = 1781 − 132.74[Siamph] + 116.6[Tiamph] − 69.41[Fe˙tamph] + 101.62[Naamph]} proposed by Putirka [2016] range from 890 to 940 °C, 960 to 970 °C, and 846 to 850 °C, respectively (Table 2).

The crystallization depth of amphibole from Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rock was therefore estimated to be 17–20 km, 30–35 km, and 18–20 km, respectively. Since the crustal thickness from the study area has been estimated to range from 40 to 45 km [Dehghani and Makris 1984], amphiboles from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks (trachyandesite) might have been formed within this crust while those of Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths have been also formed within the crust but closer to the crust–mantle boundary.

5.5. Oxygen fugacity

The differences observed in the Fe3+ content of clinopyroxene from the investigated samples could be ascribed to different oxidation and oxygen fugacity states of the magma they crystallized from [Canil and Fedortchouck 2000, Aydin 2008]. The Na, Al(IV), and Fe3+ contents of the clinopyroxenes from host volcanic rocks are higher than those of the clinopyroxene from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths, suggesting that they formed at higher oxidation conditions [Schweitzer et al. 1979]. The location of samples in Figure 4d supports such an inference. It can also be seen in this figure (Figure 4d) that clinopyroxenes from the host volcanic rock are formed in conditions of high oxidation compared to the pyroxenite xenoliths of the study area [Khezerlou et al. 2017] and Misho diorites [Shahzeidi 2013]. Also, the location of samples in Figure 5d indicates crystallization of amphibole from Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rock under high oxidation conditions.

As can be seen in Figure 5d, the amount of Fe2+ in amphiboles from Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths is lower than those of amphiboles from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks, indicating that they formed at higher oxidation conditions. Assuming that the formation pressure of amphiboles is directly related to oxygen fugacity [Stein and Dietl 2001], it is likely that amphiboles from Group 2 were formed at higher pressures than those from Group 1 and host volcanic rocks, a result consistent with the barometric estimates.

5.6. Characteristics of magma sources

The changes in composition from core to rim of amphibole from Group 1 are normally associated with a temperature increase. These compositional changes in amphibole probably suggest the injection of pulses of magma.

The amphiboles and biotites from Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths do not show clear zoning (Tables 2 and 4, respectively), suggesting their gradual crystallization and equilibration with the melt during the crystallization process. On the other hand the biotites from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths are zoned with a decrease of Al2O3, SiO2, and CaO associated to an increase of MgO, FeO, and K2O from core to rim (Table 4). It seems that during the crystallization of biotites, plagioclases also crystallized and as Si, Ca, and Al are preferably incorporated within the structure of plagioclase, that process could explain the lower concentrations of those elements in the rim of biotite crystals. As mentioned in the petrography section, plagioclases from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths are mainly intercumulus and it seems therefore that plagioclases and biotites were not accumulated simultaneously. The normal zoning observed in the plagioclase phenocrysts from the host volcanic rocks (Table 3) indicates a temperature decrease of the residual melt as crystallization proceeded.

The petrographic study (for example the presence of some coarse-grained amphiboles and biotites and euhedral amphiboles) confirms the cumulus texture of the xenoliths. Positive anomalies of U, Ba, Ti, and K in hornblendite xenoliths are probably related to the accumulation process of amphibole and biotite (Figures 9a, c).

Biotites from hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks display very low Al(VI) content, which is sometimes totally absent (Table 4), suggesting a magmatic origin [Nachit et al. 2005]. The position of xenoliths and host volcanic rocks in the ternary diagram MgO, FeO+MnO, and 10TiO2 also indicates a magmatic origin. Since the amphiboles and biotites in the hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks are of igneous type, due to the fact that amphibole and biotite are hydrous minerals and they are formed in hydrous conditions, it may be inferred that their parental magmas contained relatively high amounts of water [Otten 1984].

The anorthite content of plagioclases typically gives constraint on the water content of their parental magma [e.g. Sisson and Grove 1993]. According to Sisson and Grove [1993], the distribution coefficient of calcium–sodium between plagioclase and melt is sensitive to PH 2O, and varies from 1 to 5.5 under water-free and water-saturated conditions, respectively. As a result, the high content of anorthite is related to the high water pressure in the melt. Thus, the plagioclases from the Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths might have crystallized from a magma with a higher H2O content than that of the magma from which the Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks crystallized (Figure 6). However, the anorthite content of plagioclase may also change with the degree of crystal fractionation. The difference in isotope ratios suggests that the xenolith groups and the host volcanic rock were formed from different parental melts.

According to Anderson and Smith [1995] the Mg#of amphibole is strongly dependent on the degree of crystallization. Therefore, the difference in the Mg#of amphiboles in Group 1 (0.67–0.72) and Group 2 (0.79–0.85) xenoliths and host magma samples (0.54–0.67) could suggest different degrees of crystallization of their respective parental melts. Yet, the high Mg#of amphibole is also related to high oxygen fugacity. Therefore, the high Mg#of amphiboles in Group 2 could also point to a higher oxygen fugacity compared to Group 1 and host volcanic rocks, as suggested by the position of the samples in Figure 5d.

The Ti content in clinopyroxene may give indication on the degree of depletion of the magma mantle source [Pearce and Norry 1979]. In this regard, the difference in Ti concentration of clinopyroxene from Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths (0.19–0.21) and host volcanic rocks (1.21–1.28) may be attributed to variable depletion and degree of partial melting of their respective mantle sources. It indicates a higher enriched source for the parental magma of host volcanic rocks compared to that of the Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths. This is also confirmed by the 86Sr/87Sr isotopic ratios (Figure 10).

The lower LREE, Pb, Th, Ba and U contents and low 86Sr/87Sr ratio in Group 2 xenoliths compared to those of Group 1 indicate a more depleted mantle source for this group (Table 6). Besides, the difference in 86Sr/87Sr and 143Nd/144Nd values of Group 1 and Group 2 xenoliths and host volcanic rocks suggests also a difference in composition of their respective mantle sources [Zhang et al. 2006].

Positive Pb anomaly in xenoliths and host volcanic rocks indicates either the influence of mantle wedge metasomatism through fluids from subducting oceanic plate for the sources of magmas or contamination of magmas by the crustal lithosphere [Atherton and Ghni 2002]. Positive Ba, La, Cs, K, and U anomalies associated with negative Nb and Ta anomalies may be explained by magma contamination by crustal materials [Hofmann 1997].

In all the investigated xenoliths, a negative Th anomaly is observed (Figures 9a, c). This element has a low mobility in arc settings [Pearce and Peate 1995] due to its very low solubility in subduction zone fluids. The observed negative Th anomaly is therefore probably due to the effect of fluids released from a subducted oceanic plate. Similarly to host volcanic rocks [Khezerlou et al. 2017], negative Nb and Ta anomalies are also observed in hornblendite xenoliths and probably also reflect a subduction-related magmatism (Figures 9a, c, e) [Saunders et al. 1980, Kuster and Harms 1998]. According to Ionov and Hofmann [1995], amphibole is a very suitable mineral for storing Nb and Ta in the upper mantle and can impart negative anomalies of Nb and Ta on subduction zone magmas. Due to the high thickness of the continental crust in the study area (40–45 km), contamination of magma by crustal materials can also be effective.

As shown in Table 5, the (Ce/Pb)N ratio in the investigated xenoliths, similarly to that of host volcanic rocks [Khezerlou et al. 2017], is lower than 18 while for MORB and oceanic arc environments it is 47 and 27, respectively [Hofmann et al. 1986]. This low ratio in xenoliths and host volcanic rocks probably implies the presence of crustal materials in their parental magma sources [Yang et al. 2005]. High abundance of LREE and LILE in hornblendite xenoliths agrees with the involvement of a metasomatized upper mantle in their genesis. Previous studies on volcanic rocks [Ahmadzadeh et al. 2010] and pyroxenite xenoliths [Khezerlou et al. 2017] from the study area also evidenced a metasomatized mantle source leading to the enriched characteristics of the parental magmas.

The higher abundances of U, Ba, and K in Group 1 xenoliths compared to those of Group 2 could be explained by the higher biotite modal content of the former as these three elements are preferentially incorporated by biotite than by amphibole. In addition, the higher MREE content characterizing most of the Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths compared to those of Group 2 and host volcanic rocks could be related to their higher amphibole modal content, which is also in agreement with the higher Ti content of Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths.

The negative Eu anomaly in Group 1 hornblendite xenoliths, similar to that in host volcanic rocks [Khezerlou et al. 2017], evidence early fractionation of Ca-plagioclase from the parental magma during its journey in the crust [Willson 1989, Martin 1999, Wu et al. 2003]. On the other hand, the positive Eu anomaly in Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths is associated with high plagioclase (labradorite) modal content.

As shown in Figure 8, the amount of SiO2, K2O, and Na2O in the xenoliths is lower than that of the host volcanic rocks, and this is associated with a higher abundance of LREE (including: La, Ce, Pr and Nd) in the host lava relative to xenoliths. The higher contents of all these elements in the host lava could be related to the contamination of its parental melt by crustal material. The 86Sr/87Sr ratio of the host volcanic rock (0.709545) is higher than those of the xenoliths (Group 1 = 0.706291 and Group 2 = 0.704685), but its 143Nd/144N ratio does not differ much from that of the xenoliths. As magma contamination by crustal materials increases the 86Sr/87Sr ratio and decreases the 143Nd/144N ratio, it therefore seems that magma contamination by crustal material cannot explain the high 86Sr/87Sr ratio of host volcanic rocks. It is likely that the main cause of the differences observed between xenoliths and host volcanic rocks is related to a more enriched mantle source for the parental magma of host volcanic rocks. This explanation could also apply to the difference in the content of LREE of Group 1 and Group 2 xenoliths. The higher LREE content and 86Sr/87Sr ratio of Group 1 xenoliths compared to those of Group 2 xenoliths could be indeed related to a more enriched mantle source for the parental magma of the Group 1 xenoliths.

The high HREE content of Group 1 xenoliths compared to that of Group 2 xenoliths is probably due to the presence of clinopyroxene in Group 1 samples, because these elements are preferentially incorporated in clinopyroxene. On the other hand the low amounts of MREE of Group 2 could be explained by a lower modal content of amphibole in Group 2 compared to Group 1 xenoliths [Gertisser and Keller 2000].

The Yb content in the investigated xenoliths is lower than 4 ppm (on average 1.16). Thus, it could be considered that these xenoliths did not crystallize from primary magma [Irving and Frey 1978]: which suggests in turn that the parental magmas of xenoliths probably underwent fractional crystallization processes of garnet and clinopyroxene prior to xenolith crystallization. The lack of garnet (Group 1 and 2) and paucity (Group 1) or lack of clinopyroxene (Group 2) in the investigated xenoliths seem to confirm this.

5.7. Generation of the xenoliths

Many studies have related intra-continental alkaline rocks to the presence of mantle plumes [Hofmann and White 1982, Willson 1989]. Magmatism associated with mantle plumes is characterized by a very high production of melts [Willson 1989], which contrasts with the limited outcrops of alkaline rocks in the investigated area. Usually the shape of mantle plumes are symmetric [Willson 1989], but Khezerlou et al. [2017] have shown that the volcanic shape of the investigated area and of the Uromieh Dokhtar belt is not symmetrical being oriented northwest–southeast and almost parallel to the Zagros orogenic belt. Altogether, geochemical features of host volcanic rocks and the two groups of xenoliths such as Nb and Ta depletion are inconsistent with magmas originated from the activity of a mantle plume.

The two groups of investigated hornblendite xenoliths and host volcanic rocks display distinct LILE and LREE enrichment, Ta and Nb depletion and high Ba/Ta and Ba/Nb ratios, which are among the characteristics of subduction-derived magmatic rocks. Previous studies attributed the magmatism of Uromieh-Dokhtar zone to the subduction of the Neotethys underneath the Iranian continental crust [e.g. Nicolas 1989, Hassanzadeh 1993, Ghasemi and Talbot 2006] probably during Middle Cretaceous [Ghasemi and Talbot 2006]. This Neotethys ocean closed during the Upper Cretaceous [Nicolas 1989]. The subduction of the Neotethys led to the metasomatism of the mantle wedge located above the subducting plate.

The geochemical features of the investigated xenoliths as well as their 86Sr/87Sr and 143Nd/144Nd rations, are in agreement with the occurrence of such type of metasomatism in the northern part of Uromieh Dokhatar magmatic belt. As the subduction continued, the subducted oceanic plate was broken (slab break-off). The uplift of hot asthenosphere through the resulting slab window led to the melting of the metasomatized lithospheric mantle [Keskin 2003, Jahangiri 2007, Kheirkhah et al. 2009]. Considering the relative age of the host volcanic rocks (Plio-Quaternary), it appears that the magmatism of the study area occurred at later stages following the collision. Post-collision tension processes activated faults in the study area. As mentioned in the geological setting section, the studied alkaline rocks are commonly located along the main faults. Therefore it seems that the movement of the main faults (especially North Tabriz Fault, North Misho and Tasuj faults) has provided a path for the lavas carrying the investigated xenoliths to penetrate the continental crust. As a result, magmas were trapped during their ascent to the surface at different levels of the crust. Subsequent to their crystallization, amphiboles and micas accumulated on the floor of some temporary deep seated magma chambers. Xenoliths eventually reached the ground surface through the later magmatic activity.

6. Conclusions

Field surveys performed in the present work show that alkaline volcanic rocks from the study area are Plio-Quaternary in age. The results of petrographic studies evidence cumulus processes in these magmatic xenoliths. There are differences in REE content and 86Sr/87Sr and 143Nd/144Nd ratios as well as in the chemical composition of their constituent minerals between Group 1 and Group 2 hornblendite xenoliths. This indicates that their respective parental magmas likely were derived from different mantle sources.

The high LREE and LILE contents of both groups of hornblendite xenoliths imply the presence of metasomatized enriched mantle sources beneath the study area. It is likely that as the parental magma ascends upwards some minerals, including olivine and clinopyroxene, separated from the magma after crystallization. The resulting magmas were emplaced at different depths within the crust. An explanation for this observation is that micas and amphiboles from the xenoliths accumulated on the floor of magmatic reservoirs after crystallization in the crust and reached the ground surface through a later magmatic activity. Thermometry results using amphiboles show that crystallization depth of Group 1 and Group 2 xenoliths range from 17 to 20 km and from 30 to 35 km within the crust, respectively.

The difference in isotope ratios and the composition of the clinopyroxenes suggest that the hornblendite xenoliths and the pyroxenite xenoliths from the study area were formed from different parental melts.

Finally by comparing 86Sr/87Sr and 143Nd/144Nd ratios and chemical composition of minerals from the investigated xenoliths and Misho diorites, we may conclude that hornblendite xenoliths are not linked to the Misho diorites.

Acknowledgments

This research is a part of the Ph.D. dissertation of the first author which he accomplished with the support of the Vice Chancellor for Research and High Education of Tabriz University (Iran). Hereby, we thank authorities of Tabriz University for their help and cooperation. The authors also thank the Laboratories Géosciences Environnement Toulouse and Géosciences Marines (Brest) of France that allowed us to perform the various mineralogical and geochemical analyses.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0