Version abrégée

1 Introduction

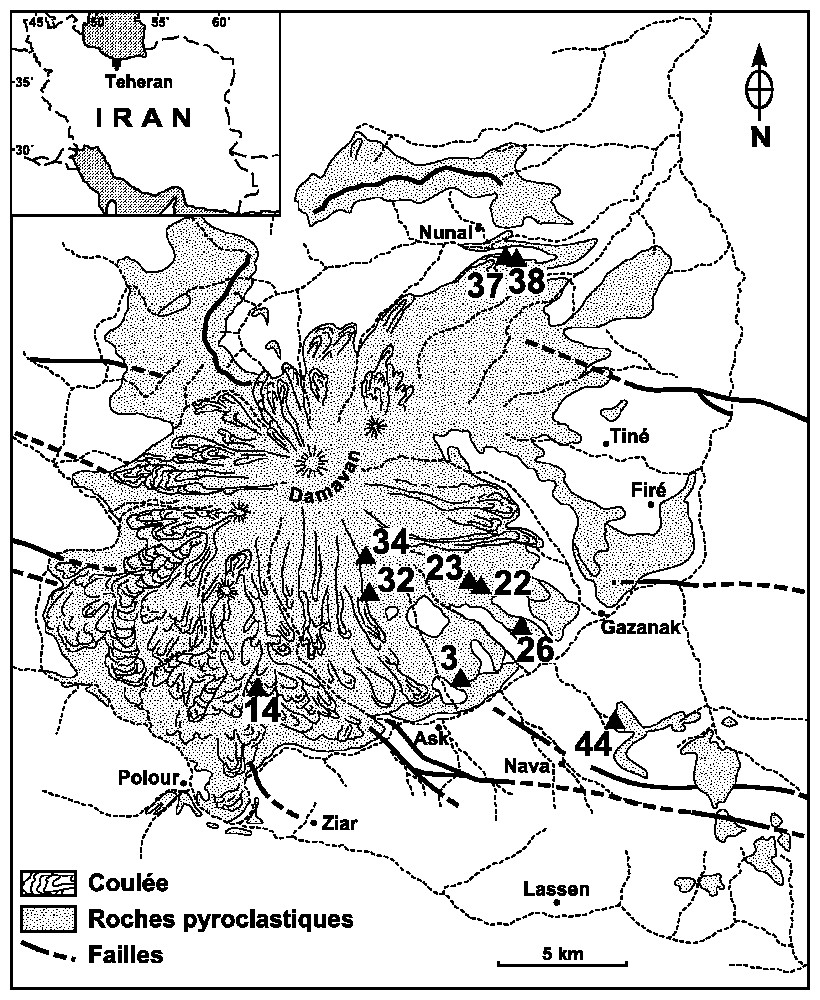

Le volcan quaternaire du Damavand, situé à 50 km au nord de Téhéran (Iran) appartient à la province volcanique du Nord de l'Iran, principalement développée dans la partie nord-ouest du pays en Azerbaı̈djan (Fig. 1). Il s'agit d'un strato-volcan, dont le sommet atteint 5 670 m d'altitude et dont le cône est essentiellement constitué par une succession de brèches pyroclastiques, de lahars et de coulées épaisses [1,9]. L'âge des éruptions est mal connu : une datation au 14C fait état d'un âge de 38 500 ans [4], des considérations stratigraphiques la situent entre le Würm (70 000 ans) et l'Holocène [5]. À noter que le Damavand se situe dans la partie centrale de la chaı̂ne de l'Elbruz, dans une région où les structures tectoniques passent d'une direction générale NNW à une direction NNE.

Geological sketch map of Damavand volcano and sampling places.

Cadre géologique simplifié du volcan du Damavand et sites d'échantillonnage.

L'association magmatique, essentiellement représentée par des laves intermédiaires, a d'abord été considérée comme alcaline [7,11]. Dans un second temps, Brousse et Vaziri [8] ainsi que Brousse et al. [9] ont établi, sur la base des éléments majeurs et des compositions minéralogiques, son caractère shoshonitique. Dans cet article, nous présentons des premières données en éléments traces, afin de préciser les caractéristiques pétrologiques des laves et de leur source.

2 Données géochimiques

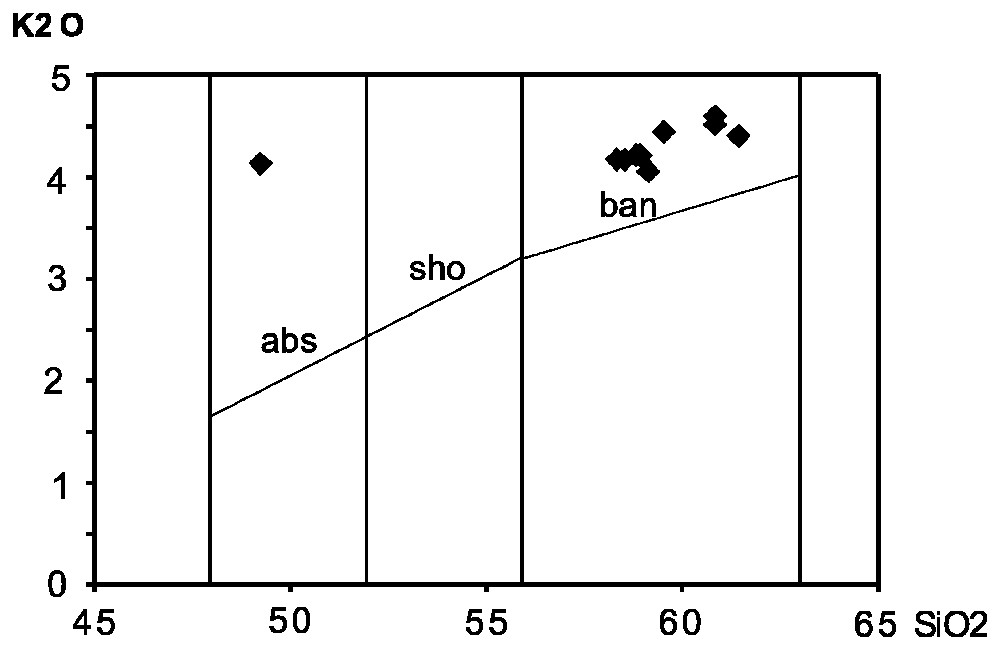

Les teneurs en éléments majeurs et traces des 11 échantillons sélectionnés sont présentées dans le Tableau 1. À l'exception de l'échantillon DH44, toutes les laves sont différenciées : teneurs en SiO2 variant entre 58,35 et 61,53 % et rapports mg compris entre 0,57 et 0,51. Leurs fortes teneurs en K2O (entre 4,03 et 4,56 %) leur confèrent une affinité shoshonitique. Cependant, leurs rapports K2O/Na2O, compris entre 0,83 et 0,96, n'indiquent pas de caractère ultra-potassique. Dans le diagramme K2O vs SiO2 [14], seul l'échantillon DH 44 (SiO2=49,33 % ; Mg=0,66) correspond à une lave primaire de type absarokite, tous les autres tombent dans le champ des banakites (Fig. 2). À noter l'absence de différence significative entre les teneurs en K2O dans l'absarokite et dans la banakite.

Major and trace elements compositions of the Damavand samples. Analyses of major elements have been performed by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP–AES, CRPG, Nancy). Trace elements were analysed by inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP–MS, University Montpellier-2, France).

Compositions chimiques en éléments majeurs et traces des échantillons du Damavand. Les analyses d'éléments majeurs ont été effectuées par spectrométrie d'émission à source plasma (ICP–AES, CRPG, Nancy), celles d'éléments en traces par spectrométrie de masse à source plasma (ICP–MS, université Montpellier-2).

| Ref. | DH 44 | DH 3 | DH 14 | DH 22 | DH 23 | DH 26 | DH 32B | DH 32A | DH 34 | DH 37 | DH 38 |

| SiO2 | 49,33 | 58,35 | 59,64 | 61,53 | 61,49 | 59,20 | 60,86 | 58,56 | 58,87 | 59,00 | 60,94 |

| Al2O3 | 15,73 | 15,84 | 15,95 | 15,99 | 15,93 | 15,89 | 15,96 | 15,93 | 16,01 | 16,00 | 15,51 |

| K2O | 4,10 | 4,15 | 4,42 | 4,39 | 4,40 | 4,03 | 4,56 | 4,14 | 4,20 | 4,19 | 4,49 |

| Al2O3 | 15,73 | 15,84 | 15,95 | 15,99 | 15,93 | 15,89 | 15,96 | 15,93 | 16,01 | 16,00 | 15,51 |

| Fe2O3 | 8,58 | 5,80 | 5,20 | 4,96 | 4,92 | 5,54 | 5,05 | 5,77 | 5,79 | 5,72 | 4,95 |

| MnO | 0,11 | 0,07 | 0,06 | 0,06 | 0,06 | 0,06 | 0,06 | 0,08 | 0,07 | 0,07 | 0,06 |

| MgO | 7,25 | 3,31 | 2,63 | 2,29 | 2,24 | 2,82 | 2,41 | 3,37 | 3,31 | 3,34 | 2,72 |

| CaO | 7,37 | 4,92 | 4,89 | 3,99 | 3,96 | 4,67 | 4,21 | 4,85 | 4,82 | 4,72 | 4,27 |

| Al2O3 | 15,73 | 15,84 | 15,95 | 15,99 | 15,93 | 15,89 | 15,96 | 15,93 | 16,01 | 16,00 | 15,51 |

| K2O | 4,10 | 4,15 | 4,42 | 4,39 | 4,40 | 4,03 | 4,56 | 4,14 | 4,20 | 4,19 | 4,49 |

| Na2O | 4,55 | 4,80 | 4,89 | 4,88 | 4,84 | 4,85 | 4,81 | 4,79 | 4,83 | 4,81 | 4,67 |

| TiO2 | 1,76 | 1,13 | 1,01 | 0,91 | 0,89 | 1,01 | 0,92 | 1,11 | 1,11 | 1,09 | 0,89 |

| P2O5 | 1,10 | 0,68 | 0,57 | 0,48 | 0,50 | 0,55 | 0,52 | 0,66 | 0,65 | 0,63 | 0,49 |

| PF | 0,35 | 1,03 | 0,81 | 0,59 | 0,82 | 1,43 | 0,72 | 0,71 | 0,44 | 0,54 | 1,08 |

| Total | 100,23 | 100,08 | 100,07 | 100,07 | 100,05 | 100,05 | 100,08 | 99,97 | 100,10 | 100,11 | 100,07 |

| [Mg] | 0,66 | 0,57 | 0,54 | 0,51 | 0,51 | 0,54 | 0,52 | 0,57 | 0,57 | 0,57 | 0,56 |

| Rb | 66,23 | 110,4 | 124,7 | 133,2 | 140,2 | 107,85 | 108,0 | 130,9 | 124,5 | 110,8 | 136,8 |

| Sr | 2 001 | 1 431 | 1 500 | 1 175 | 1 228 | 1 151 | 1 594 | 1 276 | 1 588 | 1 450 | 1 187 |

| Zr | 457 | 348 | 378 | 385 | 392,6 | 317 | 350 | 305 | 405 | 373 | 366 |

| Nb | 45,40 | 46,51 | 51,93 | 48,71 | 47,35 | 49,73 | 46,95 | 51,03 | 55,88 | 48,21 | 49,47 |

| Cs | 1,39 | 3,87 | 4,53 | 4,44 | 4,91 | 3,58 | 3,79 | 4,68 | 4,29 | 3,85 | 4,66 |

| Ba | 2 026 | 1 451 | 1 417 | 1 429 | 1 520 | 1 446 | 1 554 | 1 507 | 1 738 | 1 572 | 1 481 |

| La | 114,8 | 102,1 | 103,1 | 95,65 | 101,1 | 90,98 | 93,13 | 100,3 | 107,9 | 98,72 | 102,5 |

| Ce | 245,9 | 201,2 | 180,6 | 185,5 | 177,5 | 180,00 | 169,9 | 209,1 | 230,5 | 205,8 | 211,2 |

| Pr | 22,82 | 18,64 | 18,11 | 16,82 | 17,81 | 15,52 | 17,26 | 17,65 | 19,34 | 18,00 | 17,68 |

| Nd | 85,37 | 67,92 | 63,56 | 57,18 | 61,25 | 54,50 | 59,83 | 61,31 | 69,43 | 63,38 | 60,43 |

| Sm | 11,18 | 8,50 | 8,07 | 7,22 | 7,74 | 6,99 | 7,64 | 7,52 | 8,88 | 7,88 | 7,57 |

| Eu | 3,31 | 2,28 | 2,08 | 1,90 | 2,02 | 1,90 | 2,14 | 1,95 | 2,44 | 2,16 | 1,92 |

| Gd | 7,11 | 4,92 | 4,92 | 4,23 | 4,68 | 4,31 | 4,73 | 4,48 | 5,65 | 4,73 | 4,44 |

| Tb | 0,86 | 0,64 | 0,60 | 0,54 | 0,57 | 0,56 | 0,61 | 0,59 | 0,72 | 0,59 | 0,57 |

| Dy | 4,13 | 2,97 | 2,77 | 2,51 | 2,64 | 2,65 | 2,86 | 2,72 | 3,28 | 2,80 | 2,65 |

| Ho | 0,77 | 0,57 | 0,52 | 0,47 | 0,49 | 0,49 | 0,53 | 0,50 | 0,62 | 0,52 | 0,48 |

| Er | 1,88 | 1,47 | 1,30 | 1,19 | 1,25 | 1,23 | 1,35 | 1,32 | 1,60 | 1,31 | 1,24 |

| Tm | 0,25 | 0,19 | 0,18 | 0,16 | 0,17 | 0,17 | 0,18 | 0,18 | 0,21 | 0,18 | 0,17 |

| Yb | 1,51 | 1,23 | 1,12 | 1,00 | 1,06 | 1,03 | 1,13 | 1,13 | 1,29 | 1,10 | 1,05 |

| Lu | 0,24 | 0,19 | 0,18 | 0,16 | 0,17 | 0,15 | 0,18 | 0,17 | 0,21 | 0,17 | 0,16 |

| Hf | 9,18 | 7,20 | 7,82 | 7,85 | 7,97 | 6,43 | 7,21 | 6,53 | 8,43 | 7,34 | 7,78 |

| Ta | 2,77 | 3,35 | 3,76 | 3,52 | 3,56 | 3,47 | 3,34 | 3,79 | 3,99 | 3,39 | 3,77 |

| Pb | 14,34 | 20,02 | 18,44 | 19,87 | 19,75 | 18,01 | 18,48 | 18,12 | 20,60 | 19,13 | 20,27 |

| Th | 11,80 | 25,27 | 29,16 | 28,64 | 30,11 | 21,93 | 24,40 | 30,01 | 28,07 | 25,41 | 30,86 |

| U | 2,74 | 6,02 | 6,96 | 6,60 | 7,04 | 5,12 | 5,74 | 7,11 | 6,45 | 5,96 | 7,01 |

K2O versus SiO2 diagram, after [14].

Diagramme de corrélation K2O en fonction de SiO2 d'après [14].

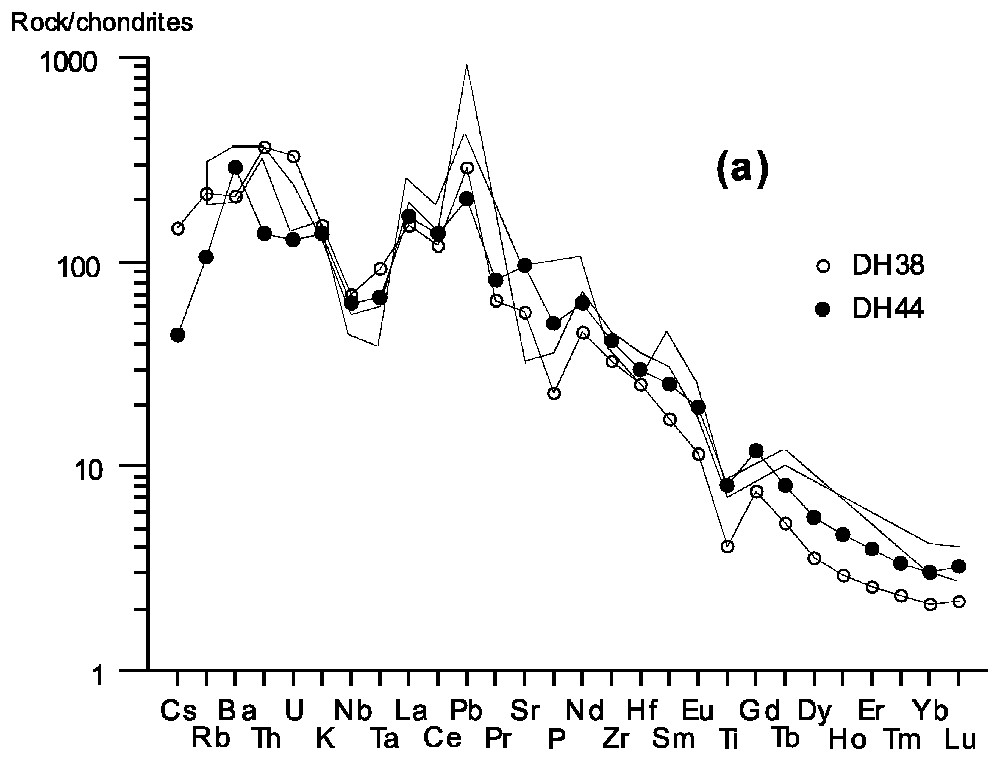

Vingt-cinq éléments traces ont été dosés sur ces échantillons : les profils de distribution normalisés au manteau primitif sont présentés sur la Fig. 4. Ces profils sont très similaires et montrent tous un fort enrichissement en éléments incompatibles, ainsi qu'une nette anomalie négative en Nb, Ta, et une moins marquée en P et Ti. On note également une anomalie positive en Pb. L'absarokite DH 44 se distingue légèrement par une anomalie faiblement négative en Th et U. Les profils en éléments traces des laves du Damavand apparaissent comparables à ceux établis sur les shoshonites du Tibet [20] : on y retrouve les mêmes anomalies négatives et positives et les mêmes facteurs d'enrichissement (Fig. 4). En revanche, les associations shoshonitiques décrites en Italie [3] ou dans les chaı̂nes américaines [12,13] montrent des différences géochimiques significatives.

Spidergrams of two selected Damavand samples. The continuous lines define the field of (a) Tibetan shoshonites [20], (b) Italian shoshonites [3,15], (c) Andean and Absaroka shoshonites [12,13]. Normalizing values of primitive mantle from [18].

Diagrammes multiéléments de deux échantillons représentatifs du Damavand. Les lignes continues délimitent le champ des shoshonites du Tibet (a) [20], d'Italie (b) [3,15], des Andes et de Absaroka (c) [12,13]. Valeurs de normalisation d'après [18].

3 Discussion et conclusion

Le magmatisme shoshonitique est classiquement associé aux zones de subduction actives ou fossiles [19,21]. Comme toutes les laves que l'on rencontre dans ce contexte, les shoshonites, y compris celles du Damavand, se caractérisent par leurs anomalies négatives en Nb, Ta et Ti. On attribue souvent ces anomalies aux processus métasomatiques ayant affecté la source de ces laves lors de la subduction. Dans notre cas, la haute teneur en K2O de l'absarokite DH44 (supérieure à 4 % et en conséquence à celle de la moyenne de la croûte [16]) pourrait indiquer la présence à la source d'une phase métasomatique riche en potassium, telle que la phlogopite. Les faibles teneurs en terres rares lourdes et les rapports La/Yb élevés observés dans tous nos échantillons suggèrent par ailleurs la présence de grenat aux résidus.

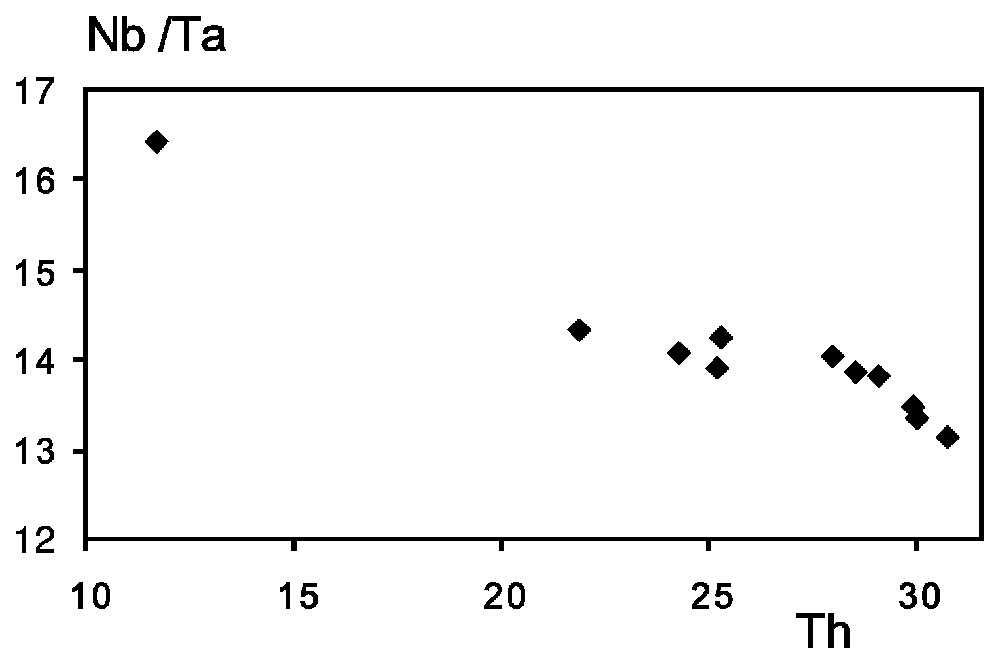

Pour certains éléments comme Th, U, Nb, Ta, Pb, les teneurs sont plus élevées dans les banakites que dans l'absarokite, ce qui est en accord avec un processus de cristallisation fractionnée. Ce processus est par ailleurs confirmé par l'évolution des rapports Nb/Ta vs Th (Fig. 5). Pour d'autres éléments, comme Ba, Sr, P, Zr, Hf et les terres rares (légères et lourdes), on note une absence de corrélation entre teneurs et degré de différenciation (Fig. 3) : ainsi, les teneurs de l'absarokite sont-elles supérieures à celles des banakites. Cette dualité géochimique suggère le fractionnement de phases particulières, avec des coefficients de partage différents pour les deux groupes d'éléments. Compte tenu des fortes teneurs en P2O5 de l'absarokite (1,10 %) et des teneurs inférieures dans les banakites (0,5–0,7 %), on peut penser à un fractionnement précoce d'apatite.

Nb/Ta vs Th diagram for Damavand samples.

Diagramme de corrélation de Nb/Ta en fonction de Th pour les échantillons du Damavand.

Correlation diagrams respectively (a) La vs SiO2, (b) Th vs MgO and (c) Nb vs SiO2. ucc: averaged upper continental crust from [16].

Diagrammes de corrélation (a) de La en fonction de SiO2, (b) de Th en fonction de MgO et (c) de Nb en fonction de SiO2. ucc : moyenne de la croûte continentale supérieure d'après [16].

Au sein du groupe des banakites, la dispersion des points représentatifs dans certains diagrammes, comme Th vs MgO ou Nb vs SiO2 (Fig. 3), ne peut s'expliquer par un simple processus de fractionnement et suggère l'intervention d'une contamination crustale. En effet, si on considère les teneurs moyennes de la croûte continentale supérieure en Th (10,7 ppm) ou Nb (25 ppm) [16], une contamination des laves va se traduire par une diminution des teneurs en ces éléments, évolution qui se dessine sur la Fig. 3. On peut également trouver là l'explication des anomalies positives en Pb observées dans toutes les laves. Cette contamination est probablement liée à des temps de résidence importants des laves dans un réservoir magmatique superficiel. L'existence d'un tel réservoir sous le Damavand est fortement suggérée à la fois par la rareté des laves peu différenciées et par la présence d'une caldeira sous sa partie nord [1].

Ces données nouvelles confirment donc le caractère shoshonitique de l'association magmatique du Damavand et son lien avec un épisode de subduction. En l'absence de données géophysiques précises, l'orientation et l'âge de cette subduction restent problématiques : soit une direction SW–NE, en relation avec la subduction miocène du Zagros, soit une direction nord–sud correspondant à une subduction naissante de la croûte océanique caspienne [2,6,8].

1 Introduction

Damavand is a young strato-volcano located in the Alborz Mountains, 50 km north of Tehran (Fig. 1). The volcanic cone (400 km2) is almost symmetrical and it reaches 5 670 m (4 000 m above the substratum) [1]. The volcanic volume is estimated between 24 and 30 km3 and consists of pyroclastic breccias and lahars interbedded with thick lava flows [2]. According to Allenbach [1], their emission would have been accompanied by a caldera formation (near Nunal). The age of the last eruptions is rather poorly estimated: a radiocarbon age determination of 38 500 years has been reported by Berberian [4]. Nevertheless, stratigraphic evidences suggest that the volcanic activity developed between Early Würm (70 000 yr) and Late Holocene [5]. Damavand was listed as an active volcano up to 1971, but it is now considered as extinct [4] in spite of the occurrence of hot springs [17] and a potential geothermal zone [21].

2 Geological setting

This isolated volcano belongs to the northern Cainozoic volcanic line, which lies from Turkish Anatolia and Iranian Azerbaidjan (with the Ararat, Sahand and Sabalan volcanoes) westward, and to the Quchan volcanic area (Kopeh Dag) eastward. Three magmatic series have been identified: ‘calk-alkaline’ (in the Sahand and Ararat volcanoes), ‘high-K calk-alkaline’ (in Sabalan) [10] and ‘alkaline’ in the Anatolian districts of Tendurek and Nemrut, in the West Iranian district of Bijar and in the East Iranian district of Quchan [5]. The Damavand is exactly located in the region where the Alborz belt trend changes from northwest to northeast.

Because of their high contents in SiO2 and alkalis, the Damavand lavas have been previously considered as intermediate alkaline latites, trachyandesites and trachytes by Jérémine [10] and Bout and Derruau [7]. From major elements and mineral chemistry, Brousse et al. [9] and Brousse and Vaziri [8] concluded that these lavas belong to a shoshonitic association. According to these authors, the Damavand magmas are related to the subduction of a segment of old oceanic crust coming from the Zagros zone after the Miocene collision.

In this paper, we present new geochemical data on Damavand lava samples, including the first trace element measurements. The origin of this series and the possible implications for the regional geodynamical framework will be discussed in the light of these new data.

3 Geochemical data

3.1 Major elements

Eleven samples have been analysed (Table 1). The SiO2 content evolves between 58.4 and 61.5 %, except for sample DH44 (49.33 %). In a similar trend, their Mg-numbers range from 0.57 to 0.51 and CaO contents are near 4.5 %, suggesting that all lavas have been affected by differentiation. Sample DH 44 is characterized by higher Mg number and CaO content ([Mg]=0.66; CaO=7.37 %). This sample, which is also enriched in P2O5 (P2O5 =1.1 %), can be considered as a rather primitive magma. The contents in Na2O and overall in K2O are systematically high (respectively between 4.55 and 4.89 % and 4.03 and 4.56 %) and they do not display any significant variations with SiO2 or MgO. In the K2O vs SiO2 diagram (Fig. 2) of Peccerillo and Taylor [14], all the samples, except DH 44, plot in the banakite field, while DH44 plots in the absarokite. The K2O content of this absarokite is quite similar with the banakites, even though its SiO2 content is the lowest. The K2O/Na2O ratios of Damavand lavas are and lower than 1 (0.83–0.96) and they exclude an ultra potassic character for this series. These variations are clearly unrelated to SiO2. Absarokite DH 44 (SiO2=49.33 %) has a similar ratio (0.90) as several banakites, while the lowest value corresponds to DH26 sample (SiO2 =59.2 %).

All these observations agree with a shoshonitic affinity for the Damavand volcanic association, although overall the shortage of shoshonite is probably a characteristic of this series, as indicated by Brousse and Vaziri [8]. Shoshonitic lavas are not scarce in Iran [2], where their ages range between Eocene and Miocene, but only the Damavand rocks are of Quaternary age. Consequently, they constitute a very important element for understanding the present geodynamical evolution of Northern Iran.

3.2 Trace elements

Twenty-five trace elements have been determined (Table 1). Globally, all lavas are highly enriched in incompatible elements (for example La ranges from 90 to 115 ppm). As illustrated in Fig. 3, the correlation between several incompatible elements and differentiation is weak or lacking, and the highest contents in some incompatible elements (e.g., La, Ba) are even found in the most primitive sample (absarokite DH 44). Although all the data plot within a restricted field, Ba, La, Sr and P show weak negative correlations with SiO2, HFS elements (e.g., Nb, Ta, Zr, Hf), Th and U are positively correlated.

The primitive mantle-normalised incompatible element spidergrams of Fig. 4 illustrate the enriched nature of the lavas and the variability in ranges of enrichment (from several times for HREE to several hundred times for Cs, Rb, Ba, Th, U, Pb). The REE display steep patterns (76<La/Yb<95). Significant negative anomalies are observed for Nb, Ta, P and K in spite of high concentrations. A smaller negative anomaly also occurs for Ti.

The trace element patterns of Damavand lavas (DL) are quite identical to those of Tibetan shoshonites (TS) [21], both for the most incompatible elements (Rb, Ba, Th, U) and for the REE and HFSE: the Nb and Ta anomalies are similar (down 80 times the primitive mantle values for TS, 60 for DL); P and Ti anomalies are also similar and Pb displays a strong positive anomaly in both cases. For comparison, the Italian shoshonitic lavas [3,13] are significantly different: for instance, they display Nb and Ta negative anomalies down to only eight times primitive mantle values and they have higher HREE. The comparison with the Andean or North America margin shoshonites [12,13] is more problematic, because of the scarcity of data and the lack of HFSE determinations. However, some trace element data on the Absaroka petrotype [13] illustrate that this lava is geochemically different: it displays, for instance, strong negative Th and U anomalies, while the Damavand samples, similar to those from Tibet, are enriched.

4 Discussion. Conclusion

Shoshonitic magmatism occurs in various geological settings, generally above subduction zones, associated with oceanic arcs [19] and continental margins. However, they also occur in postcollisional settings such as in Tibet [21]. Whatever the setting, the geochemical characteristics of this magmatism (particularly the Nb, Ta and Ti negative anomalies such as these observed in all lavas from Damavand) are classically considered as resulting from partial melting of highly metasomatised mantle, associated with present or fossil slab sinking [2,9].

In this respect, the high K2O content of the Damavand absarokite (higher than 4 % and consequently than the K2O crustal average [16]) can be only explained in terms of primary feature, which might reflect the presence of a potassic phase, most likely phlogopite, in the mantle source [20]. Another characteristic of this source is inferred by the low HREE abundances and high La/Yb values observed in all lavas. Such La/Yb values, strongly higher than in OIB (La/Yb=17 [19]), cannot be explained by simple melting process and are classically attributed to the presence of garnet in the source residual assemblage [21].

The origin of the banakite group is problematic. However, as illustrated by the Nb/Ta vs Th diagram (Fig. 5), the absarokite and the banakites appear as petrogenetically related by a fractional crystallization process. The systematic discrepancy observed between the behaviour of REE, Ba, Sr (which decrease from absarokite to banakites) and that of HFSE, Th, U, Pb, Rb (which increase) implies fractionation of mineralogical phases with different partition coefficients for these two groups of elements (high values for the first one and low for the second one). Apatite displays such characteristics. The high amount in P2O5 (>1 %) measured in the absarokite and the lower in the banakites (0.7–0.5 %) are in agreement with the participation of this mineral in the fractionating assemblage.

But several geochemical characteristics of banakites – such as the lack of correlation between LILE and SiO2 or MgO (Fig. 3) and the high variability of Nb, Ba, La contents – cannot be explained only by fractionation. The average composition of the upper continental crust has been plotted in Figs. 3b and 3c: it appears that the decrease of Th and Nb contents among the banakites can be easily explained by variable degrees of crustal contamination. Such a process would be also invoked to account for the Pb positive anomalies (Fig. 4).

Our new trace element data corroborate that the source of the Damavand lava is a mantle modified by subduction process. But the orientation and the age of this subduction remain unknown. Brousse and Vaziri [8] suggested either a SW–NE direction in relation with the Miocene Zagros subduction or a north–south direction implying the incipient subduction of the south Caspian oceanic crust [6]. More recently, Aftabi and Atapour [2] invoked only the first hypothesis. But the lack of consistent geophysical data and the ambiguity of available structural studies on this part of the Alborz chain prevent any definitive conclusion.

On the other hand, our data show clearly that the differentiation of the Damavand series is accompanied by an important crustal contamination process, probably related to the presence of a shallow magma chamber. The scarcity of primary and intermediate lavas, relative to more differentiated ones, is in agreement with long times of residence for magmas in the chamber before most eruptions. Isotopic analyses are now required to test this hypothesis and to quantify this process.