Version abrégée

1 Introduction

La déformation dans la croûte supérieure est caractérisée par l'interdépendance entre la tectonique et les processus sédimentaires [3]. La géométrie, la composition et l'évolution verticale et horizontale des matériaux sédimentaires sont souvent conditionnées par le mouvement des structures tectoniques [5,10]. On peut aussi trouver d'autres cas où la sédimentation ante- ou syn-tectonique a conditionné la position et la géométrie des structures [3,5]. Dans les bassins sud-pyrénéens, il y a de nombreux exemples de relations entre tectonique et dispositifs sédimentaires [14,15], favorisés par une sédimentation pratiquement continue pendant toute la période orogénique. On analyse, dans ce travail, les relations entre tectonique et sédimentation sur l'exemple naturel du système de plis et chevauchements d'Arro (zone sud-pyrénéenne, province de Huesca), formé à l'Éocène pendant la compression pyrénéenne. La méthodologie utilisée dans cette étude combine l'interprétation de lignes de sismique-réflexion, la cartographie géologique et la photo-interprétation, ainsi que les études de terrain.

2 Localisation géologique. Stratigraphie

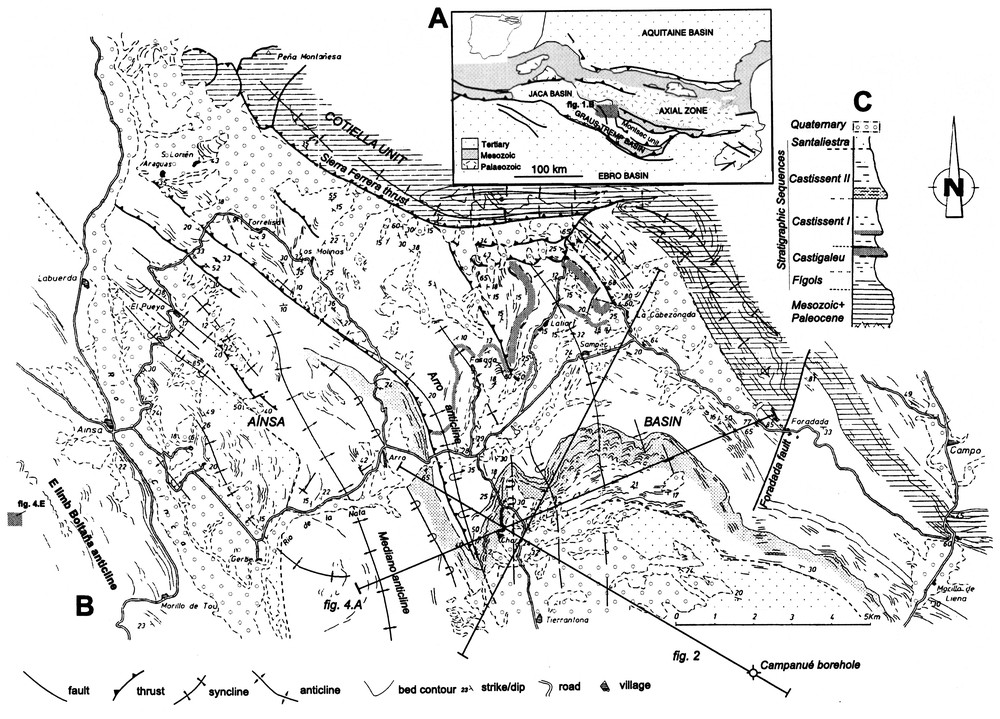

Le système de plis d'Arro, de direction dominante NNW–SSE à nord–sud, est localisé dans la partie occidentale du bassin de Graus-Tremp (Fig. 1A). Ce bassin tertiaire, à géométrie synclinale et direction WNW–ESE, a été transporté en piggyback sur les unités allochtones de l'unité sud-pyrénéenne centrale (USPC, [18]). La zone étudiée est localisée dans la partie la plus occidentale de ce bassin, appelée bassin de l'Ainsa. La zone étudiée est caractérisée du point de vue sédimentologique par la transition entre des dépôts de plate-forme et deltaı̈ques, à l'est, et des dépôts de talus turbiditique, à l'ouest. Le bassin de l'Ainsa est limité à l'ouest par l'anticlinal de Boltaña, de direction nord–sud. Au nord du bassin de l'Ainsa, le bassin mésozoı̈que du Cotiella, inversé pendant la compression pyrénéenne, chevauche vers le sud sur les matériaux turbiditiques éocènes (chevauchement de la Sierra Ferrera, Fig. 1B). Vers l'est, le contact Mésozoı̈que–Tertiaire marin peut être interprété comme une discordance en position verticale, ou à fort pendage vers le sud (Fig. 1B).

A. Location of the area studied. B. Geological map, based on photogeological interpretation at 1:30 000 scale, and field studies. C. Stratigraphic log of the syn-tectonic, Eocene series.

A. Localisation de la zone étudiée. B. Carte géologique, réalisée à partir de l'interprétation photogéologique à l'échelle et des études de terrain. C. Log stratigraphique de la série syn-tectonique éocène.

La série sédimentaire syn-tectonique, dans les structures étudiées (Éocène inférieur–moyen), est caractérisée par quatre séquences de dépôt (Fı́gols, Castigaleu, Castissent et Santaliestra, Fig. 1C), limitées par des discontinuités à l'échelle du bassin [11,12]. Elles comprennent des sédiments marins et continentaux, avec des sédiments de type turbiditique vers la partie ouest de la zone étudiée. Le système de plis d'Arro se localise dans la zone de transition entre sédiments de plate-forme (calcaires et marnes dominant dans les séquences Fı́gols et Castigaleu) et de talus (marnes et turbidites, dominantes dans la séquence Castissent). Sous l'Éocène, la série ante-tectonique des structures étudiées est composée par : (1) le Trias supérieur (faciès Keuper), qui constitue le niveau de décollement pour la plupart des chevauchements de couverture [18], (2) le Crétacé supérieur marin, calcaire, marneux et turbiditique, (3) les sédiments continentaux de transition Crétacé–Tertiaire (Garumnien) et (4) le Paléocène calcaire (calcaires à Alvéolines).

3 Géométrie des structures

Le système d'Arro est composé par quatre anticlinaux à vergence ouest et de direction NNW–SSE. La géométrie des plis peut-être définie à partir d'un marqueur stratigraphique dans la séquence Castissent (limite entre Castissent I et Castissent II dans les Figs. 1B et 1C). Leur longueur d'onde est d'environ 1,5 km. En surface, l'anticlinal d'Arro, pratiquement isoclinal, est associé à un chevauchement, avec des couches renversées dans son flanc ouest. Vers le nord, la plupart des plis changent leur direction en NW–SE (Fig. 1B), parallèles au chevauchement de la Sierra Ferrera. Les autres plis du système d'Arro sont coupés par des chevauchements à direction est–ouest, situés dans le bloc inférieur du chevauchement de Sierra Ferrera, et probablement associés avec celui-ci [7]. Vers l'est, les structures étudiées deviennent parallèles à la direction structurale générale WNW–ESE, définie par le monoclinal qui forme la limite sud de la nappe du Cotiella. L'anticlinal associé à la faille de Foradada (Fig. 1C) peut être considéré comme la limite orientale du système d'Arro. Vers l'ouest, la limite du système d'Arro est la prolongation vers le nord de l'anticlinal de Mediano (Fig. 1B).

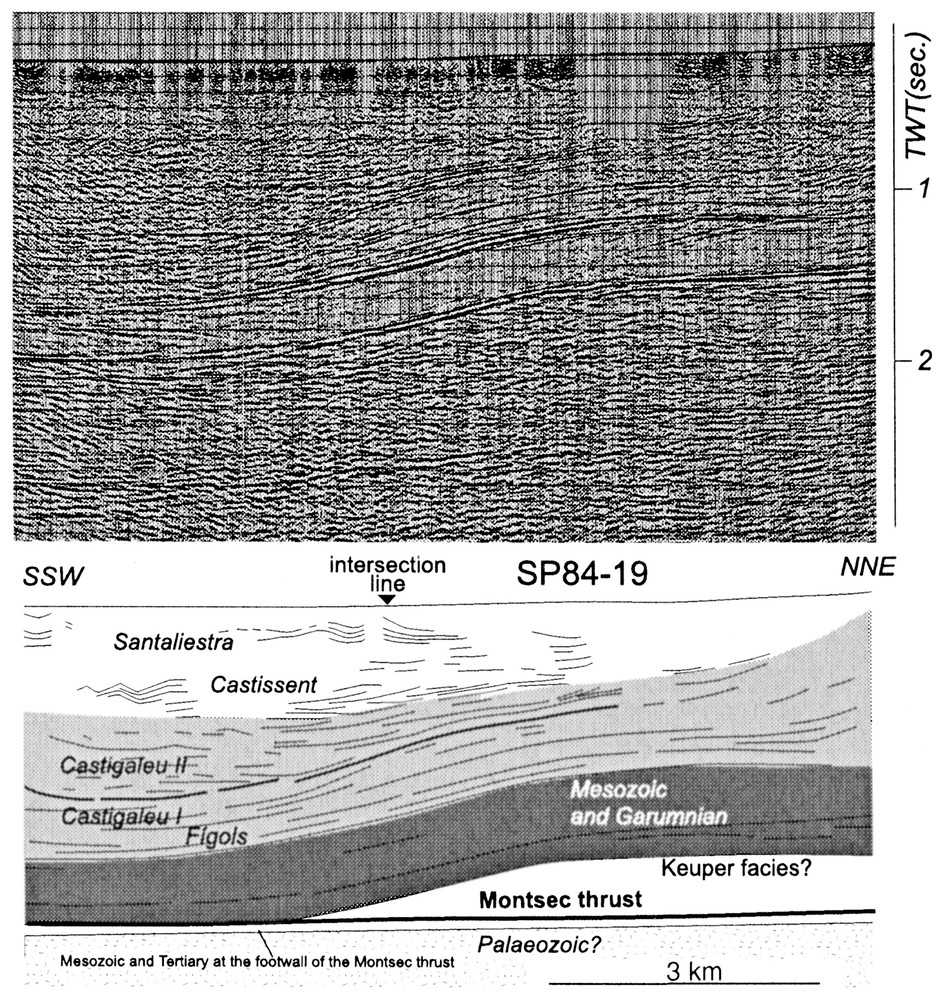

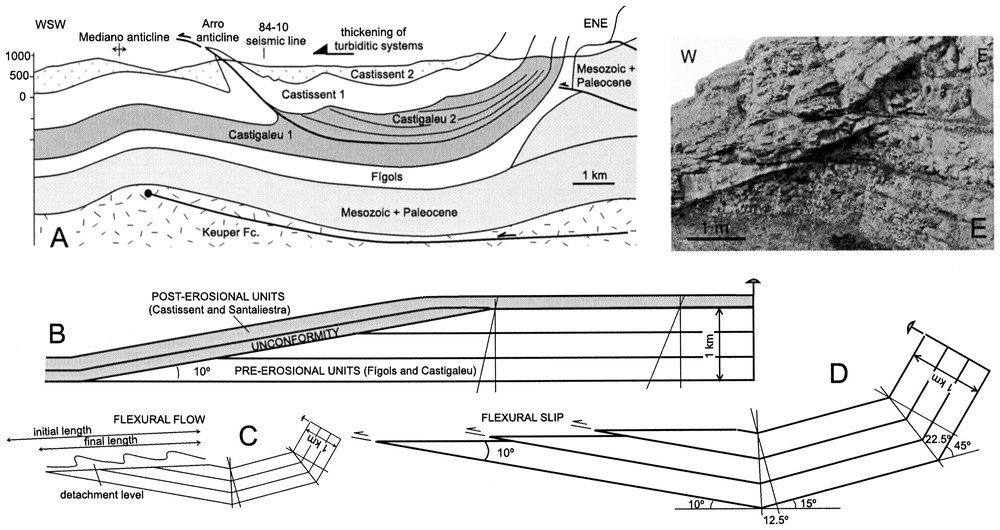

Les lignes de sismique-réflexion SP84-10 et SP84-19, interprétées à l'aide du sondage Campanué-1 ([6], voir Fig. 1B), montrent la structure du système d'Arro en profondeur (Figs. 2 et 3). La série mésozoı̈que est définie par deux réflecteurs clairs (calcaires du Cénomanien–Campanien et du Paléocène), séparés par une zone sans réflexion (marnes et turbidites du Campanien–Maastrichtien). Dans la série éocène, on peut observer une nette disharmonie entre la géométrie des unités inférieures (Fı́gols et Castigaleu) et les unités supérieures (Castissent, Santaliestra), surtout sur le profil SP84-10 (Fig. 3). Ces dernières unités sont formées par des dépôts turbiditiques dans la partie ouest de la coupe (Fig. 3). On trouve aussi dans cette coupe une discordance entre les unités Castissent et Castigaleu. Sous la discordance, les couches forment un synclinal, et l'on observe une augmentation de leur épaisseur et de leur pendage de l'est vers l'ouest, et aussi vers le sud (Fig. 2). Sur la discordance, les unités sont plissées, avec une géométrie qui peut être reliée à celle qu'on observe en surface (Fig. 4A). L'épaisseur de ces unités sédimentaires augmente aussi d'est en ouest. En revanche, les unités mésozoı̈ques subissent une diminution brusque de leur épaisseur vers l'ouest, en cohérence avec la terminaison occidentale des bassins mésozoı̈ques en extension associés à l'USPC [19]. Des structures chevauchantes peuvent être interprétées comme le résultat de l'inversion tectonique des bassins mésozoı̈ques (Fig. 3).

Seismic section SP 84-10 of the Arro fold-and-thrust system and its interpretation, also based on surface data. See location in Fig. 1B. Position of the Montsec thrust after [7].

Ligne sismique SP 84-10 du système d'Arro et son interprétation géologique. Voir localisation du profil sur la Fig. 1B. Position du chevauchement du Montsec d'après [7].

Seismic section SP 84-19 of the Arro fold-and-thrust system and its interpretation. See location in Fig. 1B.

Ligne sismique SP 84-19 du système d'Arro et son interprétation géologique. Voir localisation sur la Fig. 1B.

A. Cross-section perpendicular to the structural trend of the Arro system, drawn from surface and subsurface data. B–D. Models of fold reactivation, considering a dipping unconformity between the two sedimentary units. Kink fold geometry was used to simplify the problem, with layers of finite thickness. Kink folding implies that the length of the layers does not remain constant (although variations can be neglected in this case), if the kind fold is fixed and if the angle of the unconformity with respect to the layers is constant. B: Original position after erosion of the underlying unit and deposition of slope sediments. C: Folding of the lower series, considering deformation of the two limbs, and a pin line in one of them, with flexural flow in the free limb (not scaled with B). D: Idem, with flexural slip in the free limb (scaled with respect to B). E: Small-scale analogue for the proposed model; slump scar in the western limb of the Boltaña anticline (see location in Fig. 1A). Reverse faults in the upper unit are bedding surfaces in the lower unit.

A. Coupe géologique perpendiculaire à la structure du système d'Arro, faite à partir des données de surface et des profils sismiques. B–D. Modèles de réactivation de plis, à partir d'une discordance entre une unité inférieure horizontale et une unité supérieure sédimentée sur une pente dépositionnelle. Dans les modèles présentés, on a considéré que le cisaillement est dissymétrique, avec une ligne fixe (pin line), sans cisaillement, sur le flanc le plus penté. La géométrie utilisée dans la modélisation est de type kink, ce qui implique une légère variation (négligeable dans ce cas) de la longueur des couches, en fixant la position de la surface axiale par rapport aux couches. B : Géométrie avant déformation. C : Plissement de la série inférieure par flexural-flow, en considérant la flexion avec une ligne fixe sur le flanc droit, et tout le déplacement associé à la flexion sur le flanc libre (à gauche). L'échelle du dessin est différente de celle en B. D : Idem, avec déformation par flexural-slip dans le flanc libre (dessin à la même échelle qu'en B). E : Analogue à petite échelle pour l'exemple étudié sur une cicatrice de slump (voir localisation sur la Fig. 1A) : les failles inverses dans l'unité supérieure passent à des surfaces de stratification dans l'unité inférieure.

4 Interprétation. Modèles de réactivation des plis

La géométrie observée (Fig. 4A) peut être interprétée comme le résultat de l'érosion des unités inférieures avant la sédimentation des séquences Castissent et Santa Liestra. Cet érosion différentielle serait associée à des sillons turbiditiques, à direction nord–sud à NW–SE, qui faisaient la transition entre les plates-formes calcaires situées au sud et à l'est et les sédiments turbiditiques profonds du bassin de Jaca [17]. Cette interprétation implique une érosion de 1000 m environ sur la marge de la plate-forme, avant la sédimentation des unités correspondant à l'Éocène supérieur. Dans ce cas, la surface de discordance aurait été créée en position non horizontale, avec une géométrie de talus sous-marin (Fig. 4B).

Les différences de géométrie entre les plis de la partie supérieure de la série (système d'Arro) et la partie inférieure (à peu près monoclinale sous les plis) peuvent être expliquées par la réactivation des surfaces de stratification des unités inférieures par plissement (comme proposé par des modèles géométriques [2,4,5,21]). Cette réactivation pourrait avoir formé des chevauchements et des plis dans les unités supérieures, par un mécanisme de flexural-slip, avec des chevauchements devenant des plis vers la partie haute de la série (Fig. 4C et D), ou par un mécanisme de flexural-flow, avec raccourcissement homogène de la surface de discordance. Le plissement de la série sédimentaire serait donc associé a la formation du monoclinal et le mouvement du bloc supérieur sur le chevauchement du Montsec (Fig. 2). Dans le cas d'une réactivation par flexural-flow, le raccourcissement homogène sur la surface de discordance, associé à la formation des plis, serait de 5 % environ, valeur proche de celle obtenue dans la coupe d'Arro. Dans le cas du flexural-slip, la valeur du raccourcissement est le même, mais ce dernier est distribué en chevauchements à rejet horizontal de 300 m et vertical de 70 m (Fig. 4C et E). Ces chevauchements peuvent passer à des plis ou bien à des chevauchements dans l'unité supérieure (voir la Fig. 4A).

Les résultats obtenus par la modélisation géométrique montrent que la réactivation de la discordance intra-Éocène peut être à l'origine du système d'Arro. Ceci expliquerait le système comme un résultat secondaire du soulèvement de l'anticlinal de Mediano, à l'ouest, et de l'anticlinal-chevauchement de la Sierra Ferrera, à l'est. L'obliquité du système d'Arro par rapport à la direction générale pyrénéenne serait donc la conséquence de la direction « anomale » de ces deux structures majeures.

5 Conclusion

Le système oblique de plis et chevauchements d'Arro, à direction NNW–SSE, peut être expliqué comme le résultat du plissement de la série turbiditique (séquences Castissent et Santaliestra), discordante sur un monoclinal des unités inférieures (Fı́gols et Castigaleu). Les modèles présentés ici montrent qu'un raccourcissement de 5 %, d'ordre de grandeur similaire à celui des plis étudiés, est obtenu par un mécanisme qui combine l'érosion de la série sédimentaire, associée à des sillons turbiditiques, et son plissement ultérieur. Ce plissement serait suffisant pour former des plis et des chevauchements, avec des rejets hectométriques, dans les matériaux situés au-dessus de la discordance principale.

1 Introduction

Analogue modelling and natural examples show that there is a reciprocal conditioning between sedimentary geometry and geological structures [3]. In many cases, the geometry and nature (vertical and horizontal trends or facies distribution) of sedimentation can be directly related to contemporary structures [5,10]. In other cases, it is the geometry of pre- and syn-tectonic sediments that determines the location and sequence of structures [3,5,13]. The southern Pyrenees display a good sedimentary record, contemporary with the main compressional stages of the Pyrenean orogen. Sedimentary basins developed during thrusting as foreland basins and were later transported as piggyback basins. Syn-tectonic sedimentation allows dating of the different structures and determining their chronological relationships.

Oblique fold-and-thrust systems in the Pyrenees are associated to lateral or oblique ramps. In some cases, they have been interpreted as the result of large-scale rotations, around vertical axes, of structures parallel to the main trend of the Chain [16]. Oblique structures include detachment folds [8,14,15], hanging-wall ramp folds [20] and fault-related folds rotated clockwise after formation in the Pyrenean direction [16]. In this paper, we analyse the Arro fold system, located in the western part of the Graus-Tremp Basin (Fig. 1A and B). This basin is characterised by the transition between deltaic and platform sediments (in the east) to turbiditic systems, deposited in marine, westward-facing slopes [11,12]. The role of sedimentary geometry in the development of subsequent, compressional structures is studied and discussed. The methodology used includes photogeological studies, geological mapping and analysis of seismic reflection profiles.

2 Geological setting

The Graus-Tremp Basin (Fig. 1A) shows a gentle, syncline geometry, with a WNW–ESE trend, and defines the western part of the South-Pyrenean Central Unit (SPCU, [18]). It is filled with Palaeocene and Eocene deposits, contemporary with the main compressional stage (Lutetian–Bartonian) in the southern Pyrenees. Eocene sedimentation was deltaic in the eastern sector of the basin, passing to platform and turbiditic systems to the west [11]. The Graus-Tremp basin was transported in the hanging-wall of the Montsec thrust [9,21], forming a piggyback basin. The Aı́nsa basin (westernmost part of the Graus-Tremp basin, Fig. 1B) is limited to the west by the north–south-trending Boltaña anticline. The Eocene deposits filling the Aı́nsa basin are mainly turbidites, passing to platform sediments toward the east.

3 Sedimentary sequences

Eocene sedimentation in the Graus-Tremp basin is characterised by several depositional sequences, separated by discontinuities or unconformities at the basin scale [11,12]. The lowermost sequence (Fı́gols) consists of platform limestones (Fig. 1C). The second sequence (Castigaleu) consists of platform and slope sediments (sandstones and marls). The third depositional sequence (Castissent) consists of platform and deltaic sediments in the east, changing to turbiditic systems in the studied area. The fourth sequence (Santaliestra) consists of conglomerates in the east, also changing into turbidites to the west. In general, the Arro fold system developed in the area of transition between platform sediments and turbiditic systems.

4 Structure

The Arro fold system shows a NNW–SSE trend. The shape of folds can be defined from a stratigraphic boundary within the Castissent sequence (Fig. 1B). Folds show a westward vergence, and wavelengths of about 1.5 km. The most important fold is the Arro anticline, nearly isoclinal (Fig. 1B). It is associated to a west-verging thrust that cuts across its western, overturned limb [7]. Toward the north, the Arro anticline changes into a NW–SE trend, becoming parallel to the Sierra Ferrera thrust (Fig. 1B). The other folds of the Arro system, with a nearly north–south trend, abut toward the north against east–west thrusts located in the footwall of the Sierra Ferrera thrust. Relationships between structures and coeval sedimentation indicate the development of thrusts in piggyback sequence. Toward the east, structures become parallel to the regional WNW–ESE monocline that forms the southern limit of the Cotiella nappe. To the west of the Arro anticline, the northern prolongation of the Mediano anticline forms the western limit of the system.

Two seismic sections (SP84-10 and SP84-19, from Repsol-exploración) were used to determine the geometry of structures at depth. The Campanué borehole ([6], see Fig. 1B) and good exposure along the Esera River allow constraining the meaning of the reflectors found in seismic profiles. In seismic section SP 84-19 (Fig. 2), perpendicular to the main structural direction of the Pyrenees, the Mesozoic and Lower Tertiary can be clearly recognised, with two reflectors (Palaeocene and Upper Cretaceous limestones), separated by a barren zone (Upper Cretaceous marls and turbidites). The lower part of the Eocene sequence is concordant with the Mesozoic. Nevertheless, at the surface, the Santaliestra and Castissent are folded with a shorter wavelength (Fig. 1B), which means that a detachment must exist within the Tertiary series.

In the seismic section SP 84-10 (Fig. 3), the overall geometry of the Arro fold system can be observed: it shows a gentle syncline geometry, limited to the east by the anticline associated to the Foradada fault, and to the west by the eastern limb of the Mediano anticline. Below the Mesozoic, some horizontal reflectors, probably corresponding to Tertiary strata in the footwall of the Montsec thrust, can be interpreted. The geometry of the Mesozoic and the lower part of the Tertiary is similar to the one observed in the SP84-19 section (Fig. 2), except in the eastern part of the profile shown (Fig. 3), where an abrupt thickening of the Mesozoic series toward the East can be interpreted. This thickening is consistent with surface data [19], indicating that the maximum thickness of Mesozoic deposits is associated with the South Pyrenean Central Unit. A west-verging thrust can be interpreted as the result of inversion tectonics of the SPCU Mesozoic basins (Fig. 3).

The most remarkable feature is that in the western part of the SP84-10 profile, below the Arro fold system, there is an unconformity between the Castissent and the Castigaleu units. Below the unconformity, the beds of the Castigaleu sequence dip to the east, defining the limb of a syncline. Above the unconformity, the Castissent and Santaliestra turbiditic sequences are folded, and thicken gradually from east to west. These folds form the Arro system, as can be also assessed from surface observations (see map in Fig. 1B). This means that the Arro system cannot be associated to deep detachments (e.g. the Upper Triassic evaporites) and that its formation must be related to other mechanisms that will be discussed in the following section.

5 Interpretation. Fold reactivation model

The Arro fold system consists of turbidites folded over platform sediments defining a monocline, with an unconformity between them (Fig. 4A). The unconformity surface is sub-horizontal or dips gently to the northwest. Taking into account the turbiditic character of the upper depositional sequences, erosion of the Castigaleu sequence can be explained by the installation of a submarine canyon with NW–SE trend, in the area of the Mediano anticline. This interpretation is supported by sedimentological interpretations of the Aı́nsa area [17], as a transitional area between platforms located to the south and east, and deep turbiditic sediments in the Jaca basin (see Fig. 1A). This process would result in erosion (about 1000 m, considering the thickness of the section) at the border of the marine platform, before sedimentation of the Upper Eocene sequences (Fig. 4B).

The contrasting geometry between the upper part of the SP84-10 section (Castissent and Santaliestra units, Fig. 3, see also Fig. 4A) and the units located below the main unconformity (Fı́gols and Castigaleu) can be explained by the reactivation of bedding surfaces by flexural-slip-folding of the pre-unconformity units (Fig. 4C and D). There are several models of unconformity deformation by fold reactivation of the underlying units [1,2,4,5]. The real shortening in the units located above the unconformity from surface data is about 5% for the whole section (Fig. 4A). This amount of shortening can be achieved in models of fold reactivation (Fig. 4C and D), either by flexural-slip or flexural-flow. In the latter case, a ‘décollement’ is necessary at the level of the unconformity [5] to develop a series of detachment folds. In the case of flexural-slip reactivation, two different geometries may occur, depending on their lithology, for adapting the newly created shortening in the post-erosion units. If there is no lithological contrast between the upper and lower units, the formed thrusts continue into the post-erosion layers (e.g., Fig. 4E), whereas, if the more recent units are less competent than the pre-erosion units (e.g., Arro fold system), a series of folds will form in the post-erosion units.

6 Discussion

To explain the geometry of the Arro fold system from surface data and seismic profiles, we propose a model based on fold reactivation. There are several constraints supporting the hypothesis of fold reactivation vs fault-related folds linked with a deep detachment:

- (i) in spite of the conspicuous folding pattern in map view, the total shortening in cross-sections at surface is small, about 5%;

- (ii) according to the seismic reflection profiles presented in this work, the sedimentary units located below the main unconformity within the Eocene are dipping uniformly below the Arro system, and thrusts in the upper sequences can be considered to be bedding surfaces in the lower sequences;

- (iii) the oblique direction of the Arro system with respect to the main Pyrenean trend can be explained in this way; reactivation of the unconformity between the upper and lower sequences can be related to the uplift of two folds (the Mediano anticline, to the west, and the anticline linked to the frontal ramp of the Cotiella thrust, to the east); therefore, the Arro system would be a secondary system, linked with a shallower detachment, formed between these two oblique folds.

7 Conclusion

The Arro system can be explained as the result of flexural-slip fold reactivation of the platform sedimentary units, with syncline geometry, located below a main unconformity within the Eocene syn-tectonic series. The upper, turbiditic sequences show thrusting and folding consistent with reactivation of the main unconformity, formed by erosion of the platform before sedimentation of the turbiditic systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to François Roure for his useful suggestions and to Repsol-exploración and Dirección General de Hidrocarburos for allowing to use and copy the seismic lines shown. This work was funded by projects PB97-0997 of the DGES (Spain) and ‘Sobrarbe project’ from Elf-Aquitaine.