1 Introduction

Because of their potential impacts on human health and the environment, the toxicity effects of nanoparticles used in the emerging field of nanotechnology need to be evaluated. The properties of nanoparticles that contribute to biological perturbations are strongly dependent on their size, mineralogy (e.g., TiO2), crystallinity, and surface reactivity (Auffan et al., 2009a,b). These parameters, in turn, are directly connected to nanoparticle toxicity through redox reactions, production of oxygen or nitrogen free radicals, the dissolution of nanoparticles and release of toxic ions (e.g., Cd++, Zn++, Ag+), and the sorption and transport of metal ions or xenobiotic pollutants (e.g., As5+, Co2+, PCB).

The evaluation of the biological impact of nanoparticles must include information on the quantity of nanomaterials likely to be released into the environment. Another essential part of the evaluation process is the assessment of the dissemination of nanomaterials in the environment throughout their life cycle, from conception to production and eventual destruction or long-term sequestration. Consequently, the risk assessment must evaluate the impacts of nanomaterials on the biological components of different media and particularly on aqueous media (water column and sediments), which are strongly related to their reactivity in aqueous systems. The reactivity of nanoparticles is mainly dependent on the reactivity of their surface atoms, which is an intensive parameter dependent on interfacial energy. However, large specific surface area is not directly associated with reactivity. The lack of knowledge about nanoparticle surface properties has been a major reason for the lack of understanding of the toxicity of n-C60 (Henry et al., 2007; Huczko and Lange, 2001; Wareight et al., 2004). This example illustrates the need to couple knowledge of toxicity for biological organisms with knowledge of the physical and chemical properties and evolution of nanoparticles or nanomaterials leached from commercial products when they are in contact with aqueous media (PEN, 2009).

The purpose of this paper is to review some of the size-dependent properties of the most commonly used nanoparticles in modern nanotechnology (Ag° and TiO2) as well as several natural nanoparticles (Fe3O4, γ-Fe2O3, and β–FeOOH) and the toxicity effects of Ag°, TiO2 (anatase), and CeO2 nanoparticles on various organisms, including microorganisms, fresh water and marine algae, fishes, nematods, and plants.

2 Physical and chemical properties: redox properties, sorption, dissolution, and aggregation

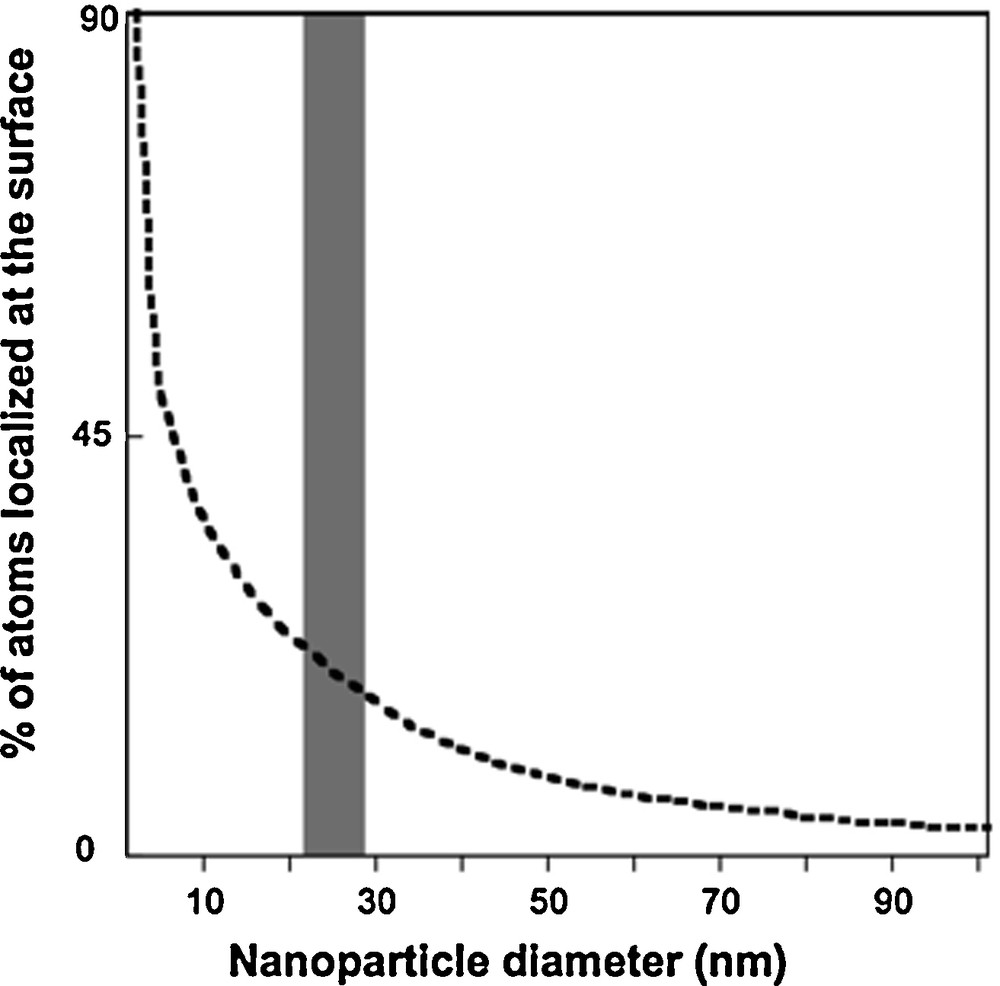

As the size of nanoparticles decreases, there is an increase in the number of surface atoms (Fig. 1). Properties such as adsorption, dissolution, and oxidation-reduction are associated with particle size as illustrated by the examples discussed below. The extent of particle aggregation is associated with particle surface charge, which can be affected by the sorption of inorganic or organic molecules.

Surface atom percentage variation with nanoparticle size (Auffan et al., 2009a,b).

Variation du pourcentage d’atomes en surface en fonction de la taille de la nanoparticule (Auffan et al., 2009a,b).

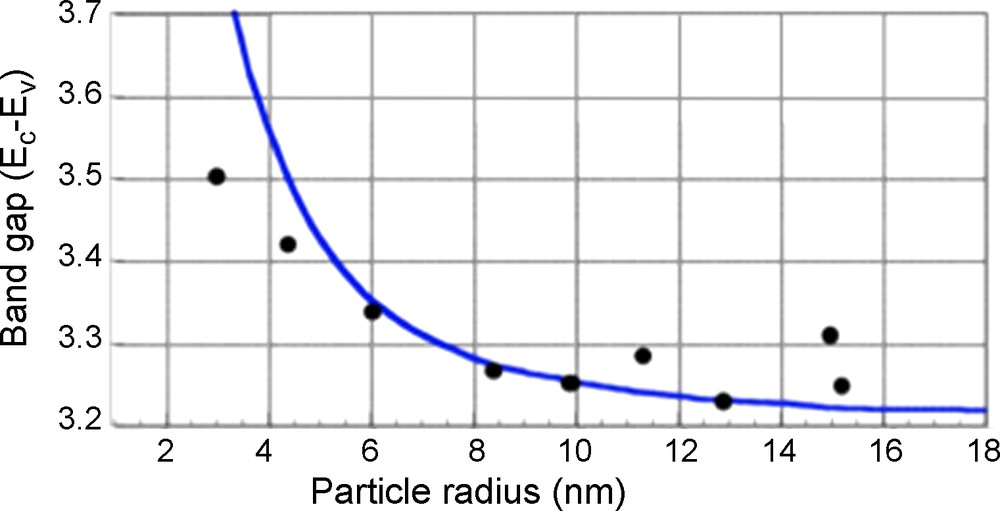

2.1 Size-effect relationship and photocatalysis: TiO2

The mineralogical species of TiO2 include rutile, anatase, and brookite. The differences in reactivity between anatase and rutile were analyzed in the 1960s (Kato and Mashio, 1964). Rutile is more thermodynamically stable for particle sizes > 35 nm, whereas anatase is stable for particle sizes < 11 nm, and the photocatalytic activity is optimum for sizes between 11–25 nm (Almquist and Biswas, 2002; Wang et al., 1997). For TiO2 particle sizes < 11 nm, the electron-hole pairs strongly recombine before reacting at the surface with an adsorbent.

The energy gap, Eb, between the top of the conduction band, Ec, and the bottom of the valence band, , is affected by the nanoparticle size, R, as reflected in eq. (1) below (Linsebigler et al., 1995; Nozik, 1993; Serpone and Pelizzetti, 1989):

| (1) |

Band transition energy (Ec-Ev) vs. the size of anatase TiO2.

Variation de l’énergie du gap optique en fonction de la taille de l’anatase.

2.2 Oxidation-reduction and nanoparticle toxicity

Chemically unstable nanoparticles may produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and may induce an oxidative stress. Nanoparticles are very sensitive to oxidation or reduction (e.g., Fe°, Fe3O4, CeO2) and, as a result, can cause important effects when they interact with bacteria (Auffan et al., 2008a,b; Auffan et al., 2009a,b; Zeyons et al., 2009). For example, ROS are produced at the surface of bacteria in the presence of CeO2 nanoparticles (Auffan et al., 2009a,b). In addition, Thill et al. (2006) showed that 50% of the mortality of E. coli occurred for concentrations of CeO2 > 3 mg/L when the nanoparticles are in close contact with the cell membrane, and they found that the toxicity is associated with the reduction of 30% of surface Ce4+ to Ce3+. One consequence of this reduction is a chain reaction resulting in lipid peroxidation within the liposaccharid layer on the cell membrane. The same types of reactions have been reported for TiO2 (Hoffmann et al., 2007).

2.3 Adsorption of pollutants: As and Co sorption onto iron oxy-hydroxides

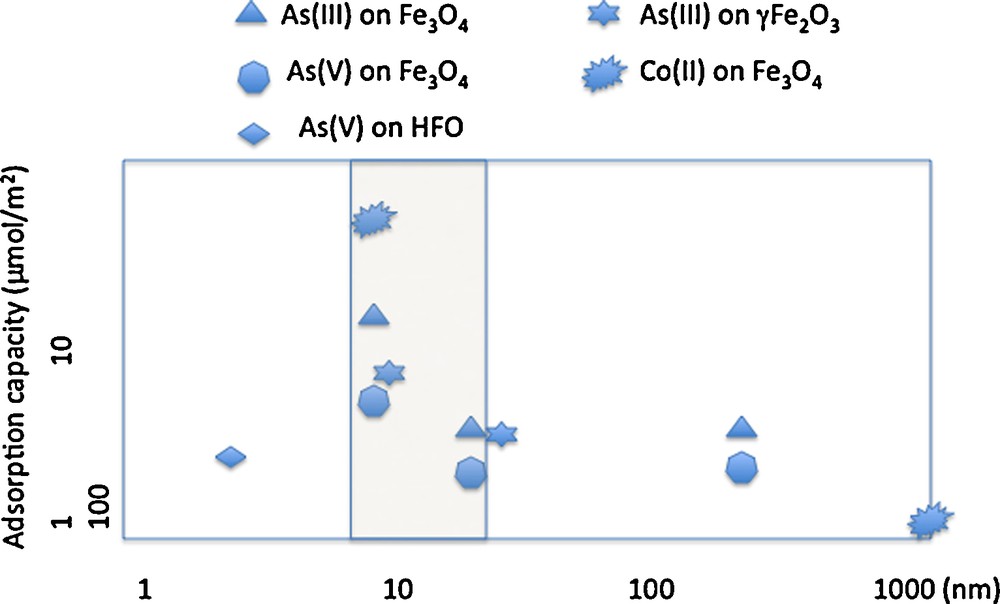

As nanoparticle size decreases, the specific surface area increases and the quantity of adsorbed ions increases. The adsorption of As(III) or Co(II) on iron oxides reveals the surface reactivity of the oxides (Table 1). Fig. 3 shows changes in the quantity of metal ions adsorbed, normalized by the specific surface area of maghemite. There is no linearity between the available surface area and the quantity of adsorbed As(III). Reactivity increases as particle size decreases for iron oxide nanoparticle sizes in the 20–30 nm range.

Capacité de rétention d’As(III), As(V) et Co(II) sur différents oxydes et oxy-hydroxydes.

| Mineral | Size (nm) | SS m2/g | Adsorbate | μmol/m2 | mmol/g | pH | References |

| Fe3O4 | 300 | 3.7 | AsIII | 5.62 | 0.021 | 8.0 | |

| 20 | 60 | 6.48 | 0.388 | 8.0 | |||

| 11,7 | 98.8 | 15.49 | 1.532 | ||||

| 300 | 3.7 | As(V) | 3.89 | 0.014 | 4.8 | Blaser et al., 2008; Borm et al., 2006 | |

| 20 | 60 | 2.54 | 0.152 | 4.8 | |||

| 11,7 | 98.8 | 6.30 | 0.623 | 8.0 | |||

| 1000 | 1.73 | Co(II) | 1.6 | 0.003 | 7.0 I = 0.1M |

Bradford et al., 2009 | |

| 11,3 | 97.5 | 58 | 5.655 | 6.9 I = 0.01M |

Brett, 2006 | ||

| γFe2O3 | 10 | 114.50 | Co(II) | 37 | 3.601 | 6.9 I = 0.01M |

Brett, 2006 |

| 6 | 174 | As(III) | 8.3 | 1.810 | 7.4 I = 0.2M |

Brice-Profeta et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2008 | |

| βFeOOH | 2,6 | 330 | As(V) | 5.4 | 1.79 | 7.5 I = 0.1M |

Chae et al., 2009 |

Retention capacity on γFe2O3, Fe3O4 and βFeOOH for As(III), As(V) and Co(II).

Capacité de rétention de As(III), As(V) et Co(II) sur γFe2O3, Fe3O4 et βFeOOH.

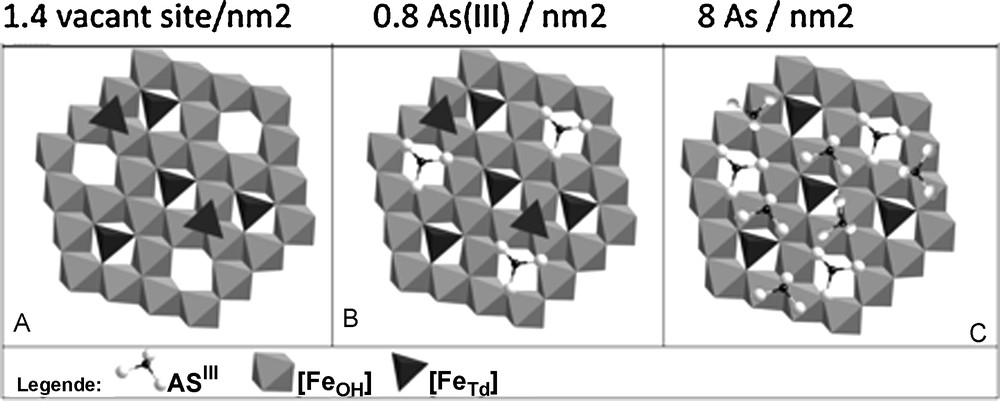

Fig. 3 shows the influence of nanoparticle size on surface reactivity when minerals are well-crystallized. In contrast, for HFO nanoparticles, which do not exhibit long-range crystallinity, reactivity is not size dependent (Deliyanni et al., 2008) Iron-oxide nanoparticles of ∼10 nm radius adsorb ∼8–10 As(III),/nm2 or 22–34 Co(II)/nm2 (Table 1) (Yean et al., 2005; Yean et al.,2006; Auffan et al., 2008a,b; Tamura et al., 1983; Uheida et al., 2006). For iron-oxide nanoparticles larger than 20 nm, the quantity of adsorbed As(III) or Co(II) drops off to 1-4 atoms/nm2. The strong reactivity of maghemite when particle size is ≥ 10 nm is due to the increase of tetrahedral vacancies (Fig. 4) (Al-Abadleh and Grassian, 2003). As(III) ions adsorb onto these vacancies, which are of two types: sites at the surface of a pentamer or hexamer of Fe[oc] and sites on the surface of a trimer of Fe[oc] (Auffan et al., 2008a,b; Morin et al., 2008). This explanation is not consistent, however, with the increased retention of Co(II) on HFO nanoparticles with decreasing size and is instead consistent with diffusion into the bulk via Fe2+ exchange (Al-Abadleh and Grassian, 2003; Brice-Profeta et al., 2005).

Different adsorption sites of As(III) onto γ Fe2O3 (10 nm). A. The initial state of the face (111). B. As(III) fullfill the Fe tetrahedral vacancies. C. The complete adsorption sites at the monolayer (Auffan et al., 2008a,b).

Les différents sites d’adsorption de As(III) sur γ Fe2O3 (10 nm). A. État initial de la face (111). B. As(III) remplit les lacunes tétraédriques. C. Sites d’adsorption correspondant à une monocouche complète (Auffan et al., 2008a,b).

2.4 Adsorption of contaminants and toxicity: TiO2

It has been shown for the Cyprinus carpio fish that co-exposure to Cd2+ and TiO2 nanoparticles results in an increased accumulation of Cd from 9 to 22 μg within the fish (Zhang et al., 2006) in the presence of 10 μg/L of TiO2. Cd and TiO2 nanoparticles are accumulated in the intestines, gills, skin, scales, and muscles. The bioconcentration factor in the gills is 152 in the presence of TiO2 and 34 in the absence of TiO2 nanoparticles. The co-accumulation of Cd and TiO2 nanoparticles in the intestines is the result of diffusion, either within the gill cells or indirectly through a trophic way and accumulation in the gastro-intestinal tract.

2.5 Dissolution and release of toxic ions

The toxicity of quantum dots to organisms is partly due to the release of Cd2+ and Se2+ after oxidation and dissolution (Derfus et al., 2004). The release of Fe2+ also results in the toxicity of ferric oxide nanoparticles (Auffan et al., 2008a,b). Two of the many parameters controlling dissolution are the solubility of the crystal and the concentration gradient at the particle/solution interface (Borm et al., 2006). Dissolution kinetics is proportional to the specific surface area of the particles and is generally faster for nanosized particles. Thermodynamically, crystal solubility, Kb, and particle size are correlated as shown by eq. (2):

| (2) |

2.6 Aggregation

The interaction of nanoparticles with biota in complex ecosystems depends also on their interaction with salts and organic molecules such as bacterial polysaccharides and proteins. The main effects of these interactions are the destabilization of the suspension and aggregation (Talapin). Competition between aggregation (interaction with solvent and solutes) and adsorption onto cell membranes will be governed by the kinetics of aggregation, which can be approximated over short times by eq.(3):

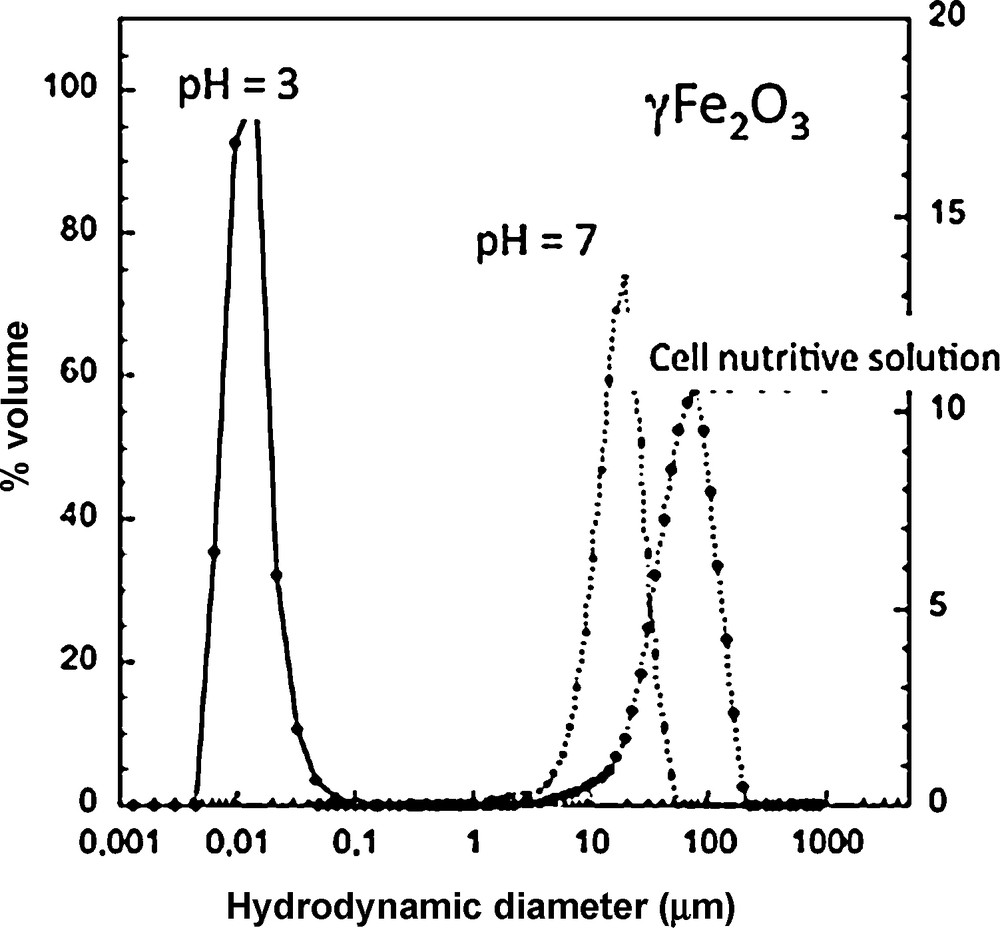

1/N(t) = 1/N(0) − 4kT/3ηt (3)where N(0) is nanoparticle initial concentration, η the viscosity, k the Boltzmann constant, and T the temperature. As an example, the aggregation of 0.5 mg/L of nano CeO2 occurs in less than one minute (Zeyons et al., 2009), vs. the characteristic adsorption time onto bacterial cell membranes of several minutes. The aggregation of nanoparticles in a culture medium can lead to micronic aggregates, as shown in Fig. 5, in the case of different nanoparticles in presence of organic molecules (Fan et al., 2006).

Aggregation of γ-Fe2O3 maghemite nanoparticles (diameter = 6 nm) in demineralized water at pH < ZPC and pH ∼ZPC and within a nutrient solution.

Agrégation de nanoparticules de maghémite γ-Fe2O3 (diamètre = 6 nm) dans l’eau déminéralisée à pH < ZPC and pH ∼ZPC et dans une solution nutritive.

As the aggregation state varies with time and chemical characteristics of the medium, toxicity must be correlated with the suspension state.

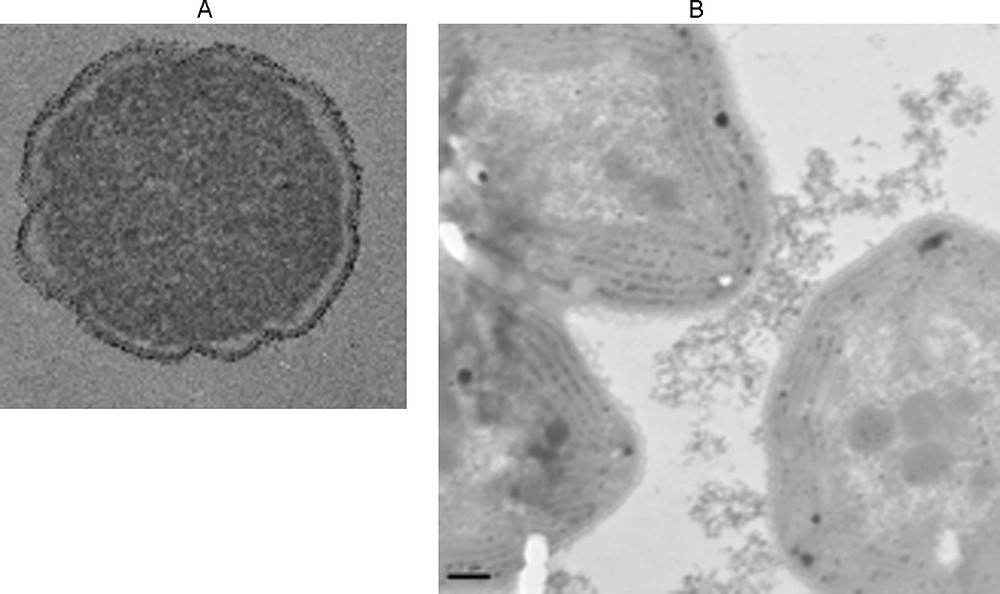

The surface properties of biological membranes are a determining factor in the toxicity of nanoparticles. It seems that direct redox effects, involving direct contact between nanoparticles and cell membranes, result in increased toxicity (Hoffmann et al., 2007; Thill et al., 2006; Zeyons et al., 2009). If the nanoparticles are aggregated and not in direct contact with cell membranes, toxicity decreases. Fig. 6 shows that extracellular polysaccharides govern the contact of nanoparticles with cell membranes. In the case of E. coli in contact with CeO2 nanoparticles, toxicity is significant even at low nanoparticle concentrations. In the case of Synecchocystis (Gram [+] bacteria), aggregation of CeO2 limits direct contacts and the toxicity is weak (Thill et al., 2006; Zeyons et al., 2009).

Exposure of bacteria to NP CeO2. A. Adhesion to the E. Coli membrane cell. B. Adhesion to the polysaccharide exopolymers of Synechocystis without adhesion on the membrane cell.

Exposition de bactéries à NP CeO2. A. Adhésion sur la membrane cellulaire de E Coli. B. Adhésion sur des exopolymères de polysaccharides de Synechocystis sans adhésion sur la membrane cellulaire.

3 Response of organisms to nanoparticles of Ag° and TiO2

3.1 Ecotoxicity of Ag°

The potential concentrations of nanoparticles in the environment can be calculated through mathematical models presented in the technical manual for chemical risk assessment of the EEC (Technical Guidance Document). The Predicted Environmental Concentration (PEC) of Ag+ in aquatic media and sediments would be 0.01–0.32 μg/L and 2–14 mg/Kg, respectively (Blaser et al., 2008; Tiede et al., 2009a). The data of Yoon et al. (2007) showed that the lowest observed effect concentration (LOEC) for E. coli is high (40 mg/L) compared to more recent data. Mueller and Nowack (2008) proposed a predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC) value of 40 μg/L. Luoma (2008) agrees with this value because Ag concentrations are unlikely to exceed 1 μg/L whatever the environmental compartment. Nevertheless, Luoma (2008) suggested a LOEC of 10 ng/L for Ag+, i.e. several orders of magnitude below the value proposed by Mueller and Nowack (2008). In a first scenario, where all particulate Ag dissolves with a typical PEC around 80 ng/L (and peaking at 1 μg/L) and a LOEC of 10 ng/L, the Ag nanoparticles themselves represent little risk since they dissolve rapidly. The released Ag+ ions, however, generate specific risks that can be determined with standard risk assessment procedures. The second scenario consists of a weak dissolution of Ag° nanoparticles. In this case the uncertainties are large, particularly regarding the influence of the morphology of the nanoparticles on toxicity. Ag° nanoparticles are incorporated in numerous industrial products (composites, clothing, food…). They are powerful bactericides because of two mechanisms: the formation of ROS, i.e. oxygen superoxide O2−, which is formed after adsorbing O2 onto the (100) and (111) faces (Akdim et al., 2008), and deregulation of the homeostatic equilibrium involving Na+, H+, Ca++, Cl− and other ions via the soluble Ag+ cation.

There are numerous studies concerning the toxicity of Ag° nanoparticles that focus on fresh and salt water bacteria as well as organisms such as nematodes (e.g., Caenorhabditis elegans) and fishes (e.g., Zebrafish, Medaka). Some studies attempt to distinguish between the effects of Ag° nanoparticles vs. Ag+ cations, as well as the influence of complexation of surface Ag or sorption onto biotic compounds such as algae on the bioavailability of Ag. Nevertheless, this aspect has received only a little attention despite its importance in modeling the bioavailability of a contaminant in complex media.

Taking into account the specificities of the different biological species, the following review will be presented by target organism.

3.1.1 Plants

Recently Barrena et al. (2009) studied the toxic effects of Ag° nanoparticles on plants (Cucumis sativus, Lactuca sativa) using germination tests, bioluminescence (using the Microtox® system), and anaerobic toxicity tests. This study revealed little or no toxicity for Ag° nanoparticle concentrations < 116 μg/L. Genotoxic effects have been observed with the onion species Allium cepa for Ag° nanoparticles smaller than 100 nm in diameter and at concentrations of 25 to 00 mg/L (Kumari et al., 2009). In the case of the yeast Candida albicans, Ag° nanoparticles (3 nm) were found to inhibit the normal budding process by disrupting cell membrane integrity (Kim et al., 2007).

3.1.2 Bacterial microorganism

Oxidative stress has been reported as a toxicity mechanism of Ag° nanoparticles towards microorganisms (Choi et al., 2008), and super-oxide anions generated at the surface of Ag° nanoparticles or Ag+ cations could be responsible for bactericidal effects (Kim et al., 2007; Pal et al., 2007). Hwang et al. (2008) studied the toxicity mechanism by using recombinant bioluminescent bacteria. Besides production of superoxide radicals acting at the cell membrane level, the Na+, Cl−… regulation is disrupted because the Ag+ cations are strongly complexed with proteins through S and P bonding within the cellular body. With wild strains of E. coli, toxicity starts at very low concentrations of Ag° nanoparticles. Their viability is decreased by 102 within 15 h at Ag concentrations as low as 900 ppb. Recently, the Highest Observed No-Effect Concentration (HONEC) was evaluated in the 2–20 ppb range (Su et al., 2009) as a function of the chemical form of Ag. The mechanisms of toxicity involve interactions with cell membrane proteins or DNA (Pal et al., 2007; Su et al., 2009). The membrane alterations may facilitate the diffusion of Ag° nanoparticles into the cytoplasm. In the case of E. coli and P. aeruginosa, the accumulation in cells of Ag from Ag° nanoparticles smaller than 10 nm was observed (Morones et al., 2005), which led to cell malformations. However, there is no evidence of the presence of metallic Ag° within the cytoplasm. The inhibition of nitrification of ammonium ions by nitrifying bacteria is more important in the presence of Ag° nanoparticles smaller than 10 nm. A correlation has been observed between the internal production of ROS and inhibition of nitrification (Choi et al., 2008).

A unique study performed with Ag° nanoparticle-impregnated polyamide showed the release of Ag+ cations, depending on particle size and important anti-microbial effects on E. coli and S. aureus after 28 days (Kumar and Münsted, 2005).

In addition, bacterial resistance to Ag° must be evaluated, as is the case for antibiotics. To date, even if the genetic mechanisms of resistance are not fully elucidated due to the variety of mechanisms by which silver affects bacteria (Chopra, 2007), it is likely that a resistance to Ag may eventually appear at sub-lethal doses (Brett, 2006).

3.1.3 Algae

For the fresh water algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the toxicity of Ag° nanoparticles (10–200 nm, average 40 nm) has been compared to the toxicity of soluble AgNO3 (Navarro et al., 2008). The toxicity measured by EC50 for Ag+ was 18 times larger than for Ag° nanoparticles. TEM showed no aggregation of Ag° nanoparticles. However, the measured Ag+ concentration in the suspension of Ag° nanoparticles by itself cannot account for the observed toxicity since only 1% of the Ag had been oxidized (Navarro et al., 2008). When normalized by the concentration of dissolved Ag+, the toxicity of Ag° nanoparticles was much more important than that of AgNO3. These results suggest the importance of interactions between the surfaces of Ag° nanoparticles and algae cells. In contrast, in the case of the marine algae Thalassiosira weisflogii, the toxicity of Ag+ is great than that of Ag° nanoparticles (Miao et al., 2009).

3.1.4 Fish

On exposure of the Medaka fish (Oryzias latipes) to polyhedric Ag° nanoparticles (50 nm, 51 nm2), Chae et al. (2009) showed a differential expression of the induced genes compared to Ag+, which showed no such effect. The Ag° nanoparticles (at 1–25 μg/L) also led to DNA and cell damage associated with an oxidative stress. The genes implied in the detoxification processes are also induced. In contrast, Ag+ cations are responsible for the induction of an inflammatory response and hepatic detoxification processes. Generally these responses to the stress are weaker with Ag+ than with Ag° nanoparticles.

In the case of zebra fish embryos (Danio rerio), a dose-response relationship (5-100 μg/ml) exists associated with mortality and delayed hatching in the presence of Ag° nanoparticles between 5 and 20 nm (Asharani et al., 2009). The mean lethal concentration varies from 25 to 50 μg/ml and depends on the development stage of the embryos, the last stage being more resistant. This toxicity appears to be specific to Ag° nanoparticles and not to Ag+ exposure since no development anomalies were detected with Ag+ concentrations between 2.5 and 20 nM. Transmission electron microscopy showed that Ag° nanoparticles were distributed in the brain, heart, vitellus, and blood of the embryos. The passive diffusion kinetics and the accumulation within the embryos are probably responsible for the dose-response anomalies (Lee et al., 2009). Bar-Ilan et al. (2009) compared the toxicity of Ag° nanoparticles or Au° of different sizes (3, 10, 50 and 100 nm) on Danio rerio. The toxicity of Ag°, as expressed in mortality rate, is the highest. Moreover, although gold nanoparticles induce weak sub-lethal toxic effects, Ag° nanoparticles induce a variety of morphological malformations of the embryos. The toxicity of Ag° depends on nanoparticle size, exposure time, and concentration. On the other hand, correlations have been established between dissolved Ag+ concentrations in equilibrium with Ag° nanoparticles coated with PVP3 and the mortality of Fundulus heteroclitus embryos. The mortality follows the solubility curve versus salinity. However, this correlation is less marked in the presence of Ag° nanoparticles coated with arabic gum (Matson et al., 2009).

3.1.5 Nematodes

Recent data obtained at Duke University (Matson et al., 2009) found a correlation between Ag+ concentration in equilibrium with Ag° nanoparticles coated with PVP and the growth of wild and mutated C. elegans strains sensitive to metals (Roh et al., 2009). The survival, growth, and reproduction of C. elegans organisms are lowered as a result of oxidative stress (Roh et al., 2009).

3.1.6 Complex media

There is growing concern about the environmental impact of Ag° nanoparticles and their bactericidal activity in connection with the loss of vital bacteria for the functioning and equilibria within ecosystems (e.g., loss of organic matter, transformations, nutrient recycling, etc.) as well as the functioning of activated sludge in wastewater treatment plants (WWTP). Recently, the impact of Ag° nanoparticles (< 100 nm) on the genetic diversity of bacterial microorganisms in estuarine sediments has been studied (Bradford et al., 2009). The results showed only insignificant modifications of bacterial diversity of sediments in contact with Ag° nanoparticles at 0–1000 μg/L.

These results must be correlated with those of Bielmyer et al. (2008), which indicated that Cl− anions do not protect against the toxicity of Ag+ for rainbow trout (Oncorhychus mykiss). In contrast, Nichols et al. (2006) showed that the complexation of Ag+ and Cl− decreases the bioavailability of Ag+ in the gills of Toadfish. Complexation of Ag+ cations by Suwannee river organic matter does not change its bioavailability (Nichols et al., 2006).

If the bacterial populations present in ecosystems are sometimes resistant to antibiotics released by agricultural or human activities (Aarestrup et al., 2000; Goni-Urriza et al., 2000), other factors such as the presence of heavy elements (Berg et al., 2005; Wright et al., 2006) can also enhance this resistance. A recent study (Mühling et al., 2009) estimated the potential link between Ag° nanoparticles and resistance to antibiotics. No increased resistance due to Ag° nanoparticles was observed; multiple abiotic factors and, in particular, salinity are likely to lower the anti-bacterial activity of Ag° nanoparticles (Lok et al., 2007). Complementary studies are needed to evaluate the bioavailability of Ag° nanoparticles released from nanomaterials into natural environments.

3.2 Ecotoxicity of TiO2

There have been a number of studies of the ecotoxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles. For example, Mueller and Nowack (2008) evaluated the PEC and PNEC values of TiO2 in the environment and predicted that PEC values (0.7–16 μg/L) will be larger than PNEC values (0.1 μg/L). TiO2 nanoparticles have a larger PEC/PNEC ratio than Ag° nanoparticles or CNT. In addition, recent studies (Hoffmann et al., 2007; Ju-Nam and Lead, 2008) have shown that ROS production in the presence of light is the main origin of toxicity of TiO2 towards aquatic organisms or micro-organisms (Oberdörster et al., 2007). Inflammatory damage and respiratory stress have been observed for fish (Federici et al., 2007), and the production of ROS is associated with radical reactions, which induce lipid peroxidation in the bacterial lyposaccharidic layer.

3.2.1 Bacterial microorganisms

The comparison between nanometric and micrometric TiO2 shows that in the presence of micrometric particles the effects are weak for E. Coli or Bacillus. The reasons are mainly the lack of contact between the cell membrane and TiO2 nanoparticles (Nedtochenko et al., 2005; Sunada et al., 2003).

3.2.2 Algae

The toxicity of nanometric and micrometric TiO2 has been studied with various algae types such as Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata using the growth tests, normalized by OECD (OECD 21), in the presence and the absence of light. Nanometric TiO2 was more toxic (EC50 = 5.83 mg/L) than micrometric TiO2 (EC50 = 35.9 mg/L), and the PNEC was 0.98 mg/L for nanometric TiO2 vs. 10.1 mg/L for micrometric TiO2 (Aruoja et al., 2009). TiO2 nanoparticles form aggregates in contact with the outer membrane of algae. Studies of the unicellular algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii showed responses at different physiological, biochemical, and genomic levels. Growth was inhibited during the first three days, and an oxidative stress was detected after 6 h by lipid peroxidation analyses. Four stress genes (sod1, gpx, cat, and ptox2) were expressed for TiO2 concentrations of 1 mg/L at 1, 3, 5 and 6 h of contact, and their concentrations were proportional to that of TiO2. The cell number after 6 h was found to be dose-dependent.

3.2.3 Fish

A very complete study of the exposure of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to TiO2 nanoparticles (Nedtochenko et al., 2005) showed toxic effects at the level of gills in the form of a proliferation of epithelial cells as well as edema of the gill filaments. In contrast, blood parameters showed only very little modifications. An increase of Na+ and K+ ATP-ase activity and a decrease of the reactive substances of TBARS indicate possible effects on osmoregulation and oxidative stress in the gills. These effects were also observed in the gut as well as in the brain but not in the liver of rainbow trout. From these results, the direct exposure route seems to be more important than the trophic one. Unfortunately, the mechanisms leading to the presence of TiO2 nanoparticles in internal organs of rainbow trout are still not elucidated. The particles may enter carried in the bloodstream via gill cells (direct exposure) or after crossing the gastro-intestinal epithelium after a trophic exposure.

3.2.4 Aquatic invertebrates

Three studies of the exposure of crustaceans (Daphnia magna, Thamnocephalus platurus) to nanoparticles and microparticles of TiO2 reached the following conclusions: there are no toxic effects below 20 mg/L (Heinlaan et al., 2008) and no cyto- or genotoxic effects (Lee et al., 2009). However, there are effects on reproduction in six out of 25 tests after 25 h of contact. The EC is between 0.5 and 91.2 mg/L. The measure of reproduction is more sensitive than the mortality. After 21 days, the NOEC was 30 mg/L for mortality and 3 mg/L for effects on reproduction. The E10 and EC50 values for reproduction were 5 and 26.6 mg/L.

4 Conclusions

Present knowledge of the effects of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles on (micro-)organisms in ecosystems is limited to studies that have evaluated interactions between one nanoparticle and one organism. Nevertheless, apparently reliable data concerning at least two nanoparticles (Ag° and CeO2) are available. These two nanoparticle types cause significant toxicity at low concentrations. The dissolved forms of silver, Ag+ as well as Ag° nanoparticles, are toxic at low concentrations. CeO2 is genotoxic at environmental concentrations (< 1 mg/L). Redox phenomena that result in the production of ROS are partly responsible for the toxicity of CeO2. The homeostatic unbalance for a series of ions Na+, Ca2+, K+… is also related to the toxicity of CeO2. Concerning nano TiO2 which could concern large quantities in very important products as cements, sun-creams… (AFSSET, 2010) and large production (Robichaud et al., 2009) it seems their toxicity is mainly due to the production of ROS due to their photoreactivity. Nevertheless other mechanisms as osmoregulation and transfer within organs are not elucidated. It seems also that the PEC/PNEC ratio is larger than for Ag°. As Nano TiO2 will be used in many products, a particular attention should be paid on the nanoresidues issued from the degradation of nanoproducts, i.e.: quantity of nanoparticles released in the environment, transfer in the ecosystem compartments, photoactivity, and long term ecotoxicity which could affect the biodiversity.

There is an absolute necessity to develop more systemic approaches in evaluating the toxicity of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles in complex ecosystems that take into account transfer and distribution mechanisms in the ecosystems (stable suspension, sediments, porous medium) as well as toxicity all along the trophic chain. These studies should be carried out in mesoscosms, which will allow definition of exposure and the hazards at environmental concentrations. Finally, risk assessment models, taking into account the life cycle of nanoparticles, should also include already commercialized consumer products.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Research (CNRS) and the French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) for their support and funding the International Consortium for the Environment Implications of Nanotechnology (GDRi iCEINT). The ANR (National Research Agency) is acknowledged for funding the project Aging Nano Troph (ANR-08-CESA-001-01).