1. Introduction

There are many past and recent studies on pollen fluxes in current deposits in Africa. Some have been the subject of attempts to model paleoenvironments and paleoclimates by various authors [Elenga et al. 2000, Jolly et al. 1998a, Lebamba et al. 2009b, Peyron et al. 2006], current [Bengo 1996, Frédoux and Maley 1996, Hooghiesmstra et al. 1986], and fossils [Bengo and Maley 1991, Dupont and Agwu 1991, Elenga et al. 2004, Giresse et al. 2009, Lebamba et al. 2009a, Lézine et al. 2009, Ngomanda et al. 2008, Reynaud and Maley 1994]; and others, have shown the importance of wind contributions to the Sahara [Nguestop et al. 2004], and Sahel winds blowing north and which contributed to the loess deposits in Europe [Haerserts 1985].

But what about the origin of the terrigenous deposits of the southern part of the Gulf of Guinea which we know that the winds of the Harmattan blowing towards the ocean, pass over the northern limit of the Gulf, and hardly exceeding the Forest/Savannah limit in Cameroon?

Thus, the research questions that this work must answer are:

- Are the pollen flows covering the bottom of the Cameroonian basin brought back by the Harmattan?

- Otherwise, how can we prove that they are part of the procession of fluvial contributions?

The choice of the Sanaga basin is justified by the fact that the Sanaga River, through its main tributaries, successively crosses large plant units (savannah, dense forest and coastal forest). This study thus aims to characterize the origins of pollens and the dominant mode of transport of pollen inputs to the continental shelf. Since the continental winds are weak, the hypothesis of wind inputs can be excluded, or else these inputs are negligible. The importance of fluvial inputs remains to be demonstrated, for example if specific savanna pollens could be found in samples taken downstream in forest areas.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study site

2.1.1. Location and climate

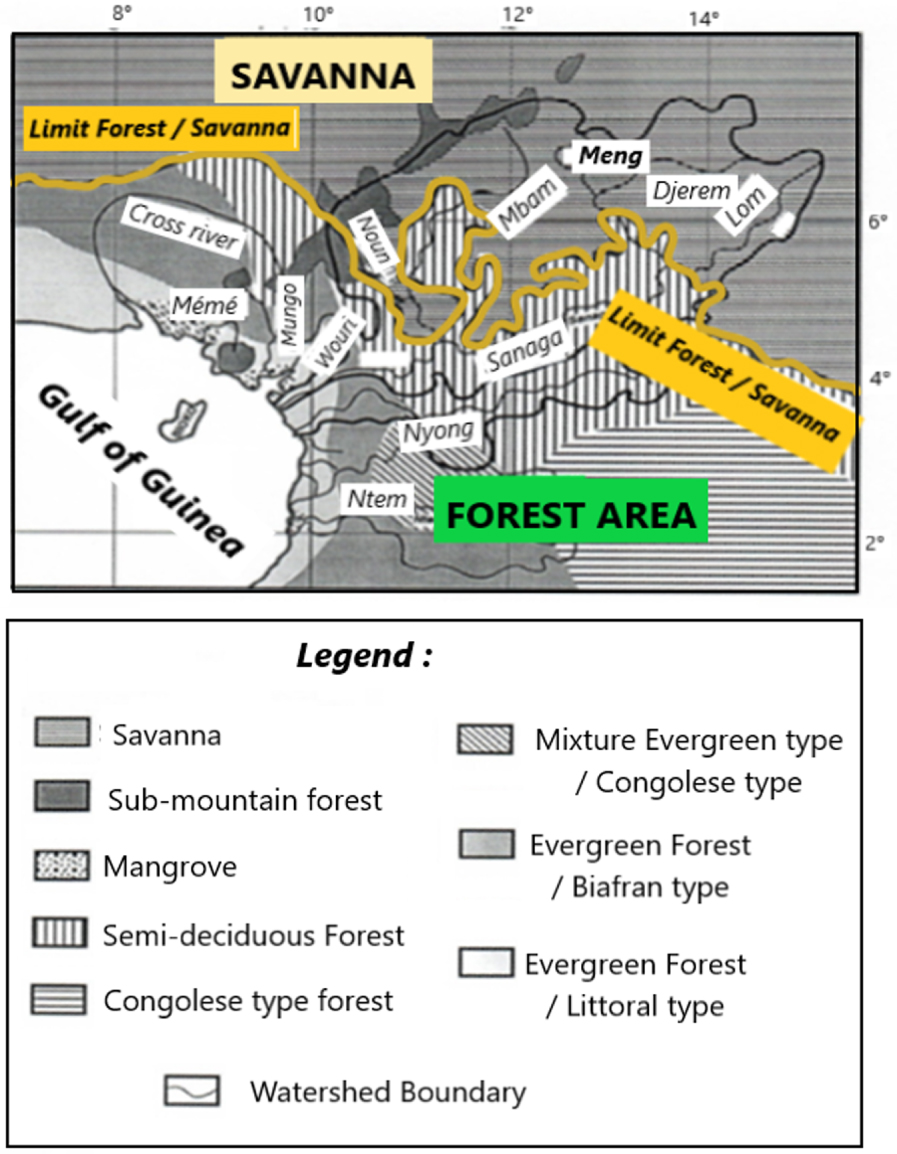

The study area occupies the central region of Cameroon (Figure 1), including the large Sanaga Basin and the coastal basins facing the Atlantic Ocean. The Sanaga Basin, with an area of 133,000 km2, extends between latitudes 3-32′ N–7-22′ N and longitudes 9-45′ E–14-57′ E [Laclavère 1979]. It is bounded to the west by the Cameroonian volcanic Dorsale, and to the north, by the Adamaoua Plateau. The Sanaga Basin is subject to the moist monsoon air masses that flow from the ocean to the mainland, and incidentally in its northern part, to the winds of the Harmattan direction NE that blow from the continent to the ocean [Leroux 1983, Piton et al. 1987, Suchel 1988].

2.1.2. Soils and vegetation

Plant units have a zonality in relation to soils [Martin 1966, Segalen et al. 1967] mainly ferralitics related to the quality of substrate [Guillet et al. 1996, Nzila et al. 2018], and the more or less important annual distribution of precipitation and temperatures (Figure 2). Wet dense forests in the south, savannahs in the centre and north of the country [Aubréville 1948, Letouzey 1985, White 1986]. Dense humid forests are made up of semi-deciduous forest, evergreen biafran forest, and evergreen littoral forest, each of which is characterized by specific taxa [Puig 2001]. Savannahs are of two types on the way to the Adamoua Plateau in the north: the grassy and shrub-rich peri-forest savannahs (Bridelia ferruginea, Terminalia glaucescens, …) and the Sudan-Guinean savannahs that are enriched by new species (Combretum molle, Daniellia oliveri, Entada abyssinica, Syzygium macrocarpum, …). Plant associations linked to specific edaphic or climatic conditions are present, such as: near the coast, mangroves at Rhizophora mangle, Avicenia africana [Boyé et al. 1975, Letouzey 1985, Din 1991]; and at altitude, the mountain formations at Podocarpus, Olea, Rapanea [Maley et al. 1987]. Moreover, anthropogenic actions related to logging, industrial and food crops do not prevent the regeneration of the forest, which is currently advancing on the savannah [Letouzey 1985, Maley et al. 1990, Youta Happi 1998].

2.1.3. Fluvial inputs of the Sanaga River

Continental erosion depends mainly on soil condition and vegetation cover. On the Edea station, the average turbidity, corresponding to all the suspended solid matter of the Sanaga basin transported to the ocean, was estimated annually at 6,000,000 tons of silt and clay, of which 2,500,000 from the Mbam by the importance of agriculture in The Bamiléké [Nouvelot 1972, Olivry 1977].

2.2. Sampling

The Sanaga River is fed along its course by several rivers that drain small basins covering various ecological and floristic areas. Mineral and organic particles of different sizes are deposited on the riverbed or on the banks. In order to be likely to find pollen grains, sampling was done in fine leashes or deposits of the lutite class, namely silts and clays. These leashes, considered surface deposits, can contain both river-drained inputs and the fallout from atmospheric dust laden with local or even allochthon pollens. Samples were taken throughout the basin, along the Sanaga River and on a dozen of its tributaries. A total of thirty-eight samples (Table 1 and Figure 3) were collected, including twenty-seven from upstream and downstream of the Sanaga Basin, and another 11 samples were taken near the offshore outlets of the main coastal rivers draining only watersheds located in dense forest areas, in order to reassure ourselves of the assumption of a dominant mode of transport.

Location of samples on rivers.

Distribution of the samples taken in the different rivers and under different floristic facies

| River | Savanna | Forest | Mangrove | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanaga | 1 | 9 | 10 | |

| Mbam | 6 | 6 | ||

| Djerem | 5 | 5 | ||

| Lom | 2 | 2 | ||

| Noun | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Yong | 1 | 1 | ||

| Mémé and Lobé | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Wouri et Mungo | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Nyong | 2 | 2 | ||

| Ntem | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Total | 16 | 19 | 3 | 38 |

2.3. Pollen identification

After the treatment of samples using conventional methods [Cour et al. 1974, Faegri and Inversen 1975], the identification of pollens was made at the level of the Family, Gender and Species by referring to the blades of the Reference Collection of current pollens of the Montpellier Laboratory and monographs of the region [Bonnefille and Riollet 1980, Caratini et al. 1974, Salard-Cheboldaeff 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983].

2.4. Statistical analysis of data

Data placed in a contingency array matrix [Benzécri 1980, Volle 1993] is preparing for multivariate analyses, such as Factor Correspondence Analysis (FCA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). These analyses are supplemented by a Dendrogramm hierarchical classification (Clusters analyses and Neighbour joining), so as to define the relationships and nuclei of affinities between the samples [Roux 1985]. Data processing, graphic representation of results, and dendrogram of hierarchical classification were made with MacMul, GraphMu and MacDendro software [Thioulouse et al. 1990] and PAST software [Hammer et al. 2001]. In the study region, this type of statistical analysis has recently been adopted on current pollen [Jolly et al. 1996] and fossil [Reynaud-Farrera 1995].

2.5. Pollen spectra

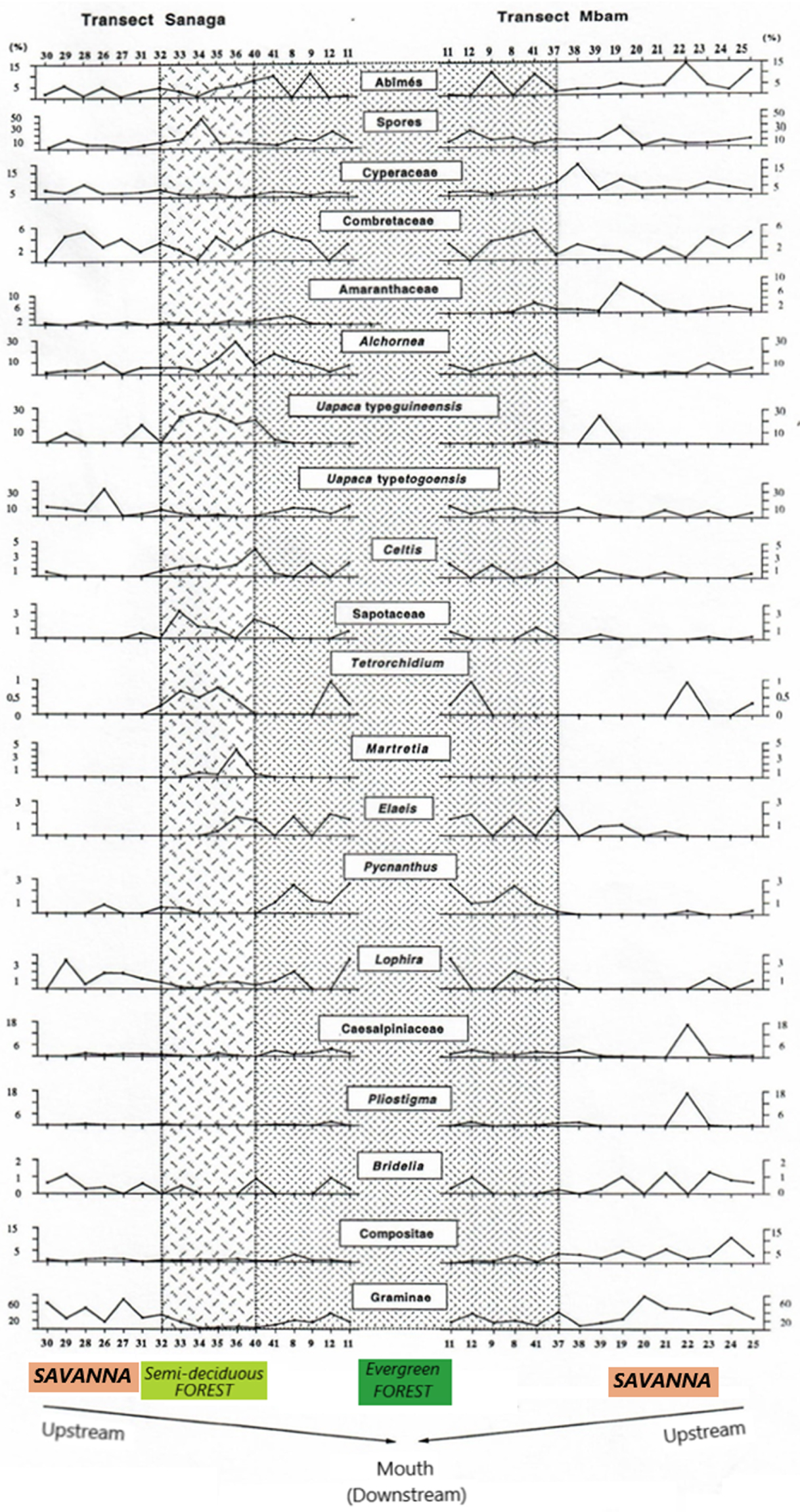

Pollen spectra are analysed using two transects from upstream to downstream (mouth), i.e. from savannah areas to dense forest areas:

- a Mbam transect with 10 samples from the Mbam Basin;

- and a Sanaga transect consisting of 12 samples taken upstream of the Sanaga/Mbam confluence.

From the downstream confluence of the Sanaga and the Mbam to the mouth, five samples complete the two transects mentioned above. These allow tracking the variation in samples along the route, from their area of origin, appearance or abundance in the samples to the mouth, of certain characteristic taxa revealed by the statistical processing of the data.

3. Results

3.1. Pollen analysis

The pollen analysis of the 38 samples resulted in the identification of 237 taxa, the most represented of which are carried out in Table 2.

Initial matrix of frequent taxa in various plant ecosystems

3.2. Multivariate analyses

3.2.1. Factor Correspondence Analysis (FCA)

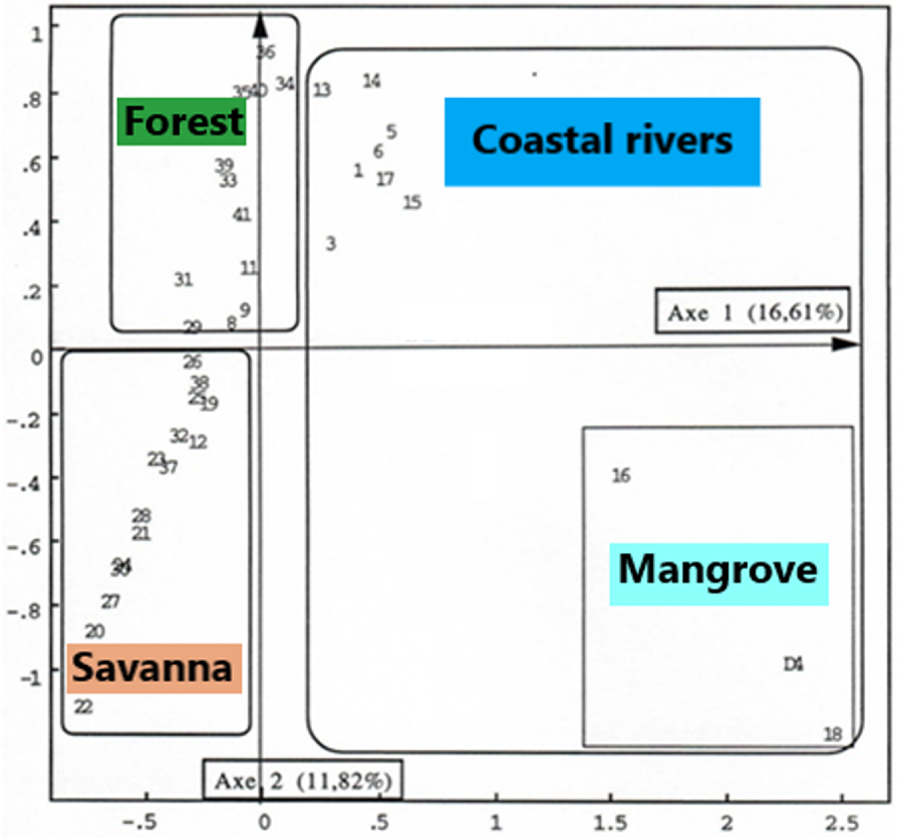

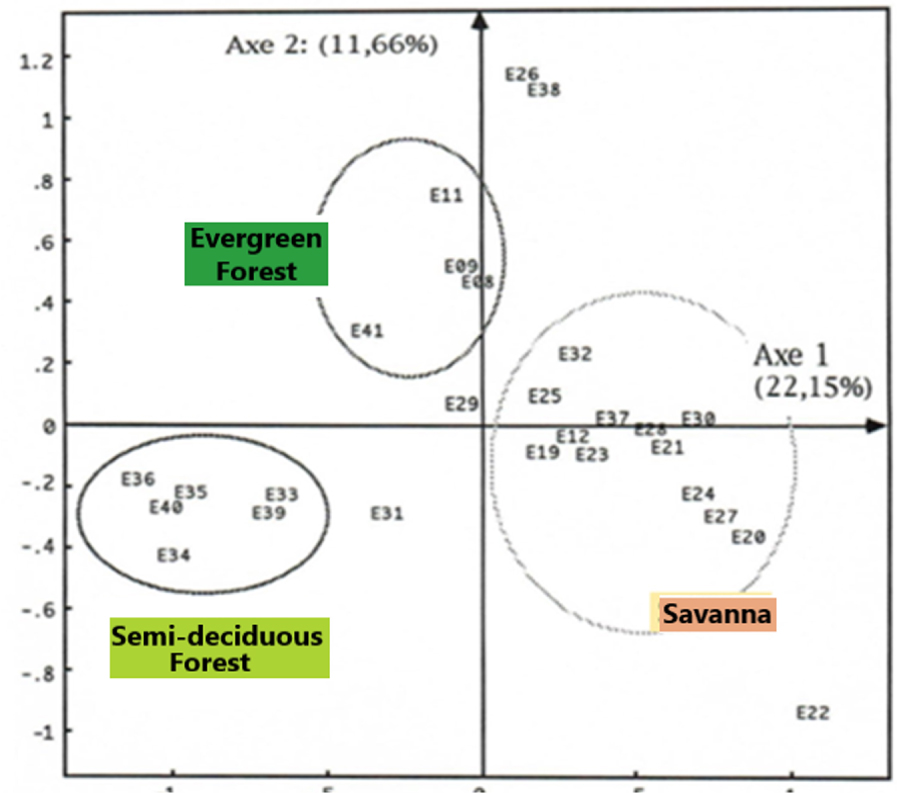

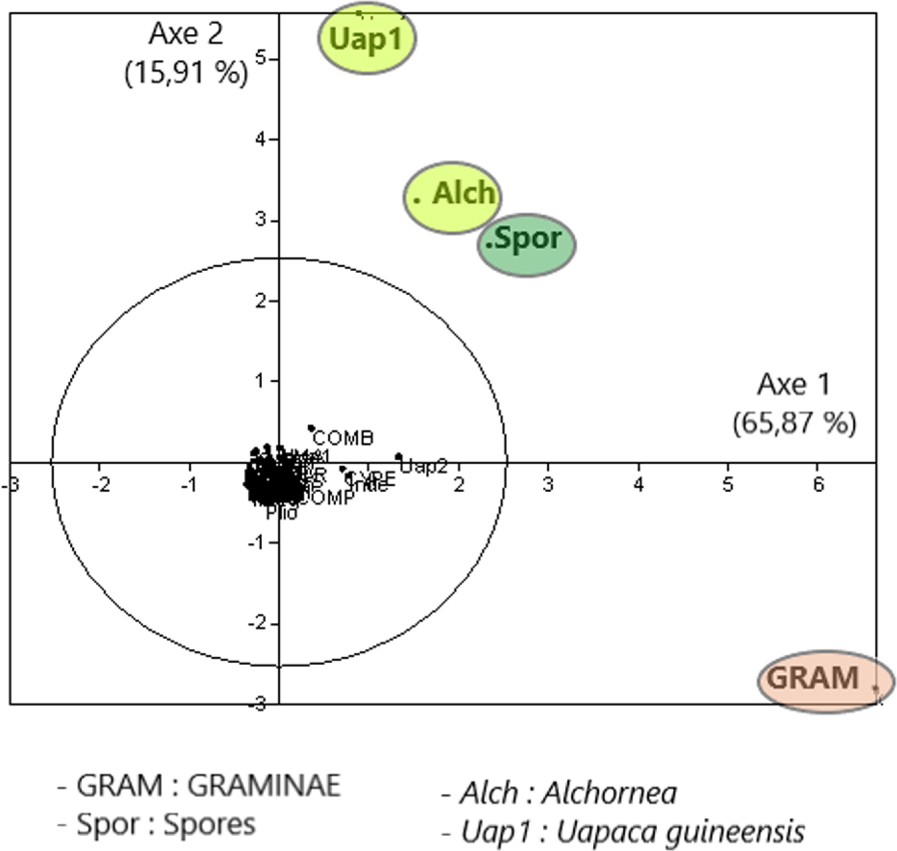

Factor analysis of the matches was applied to two separate matrixes, the initial matrix containing all the analysed samples (Figure 4); the other includes only samples from the Sanaga Basin (Figures 5 and 6).

With all samples (38) and taxa (237).

All samples, without Rhizophora.

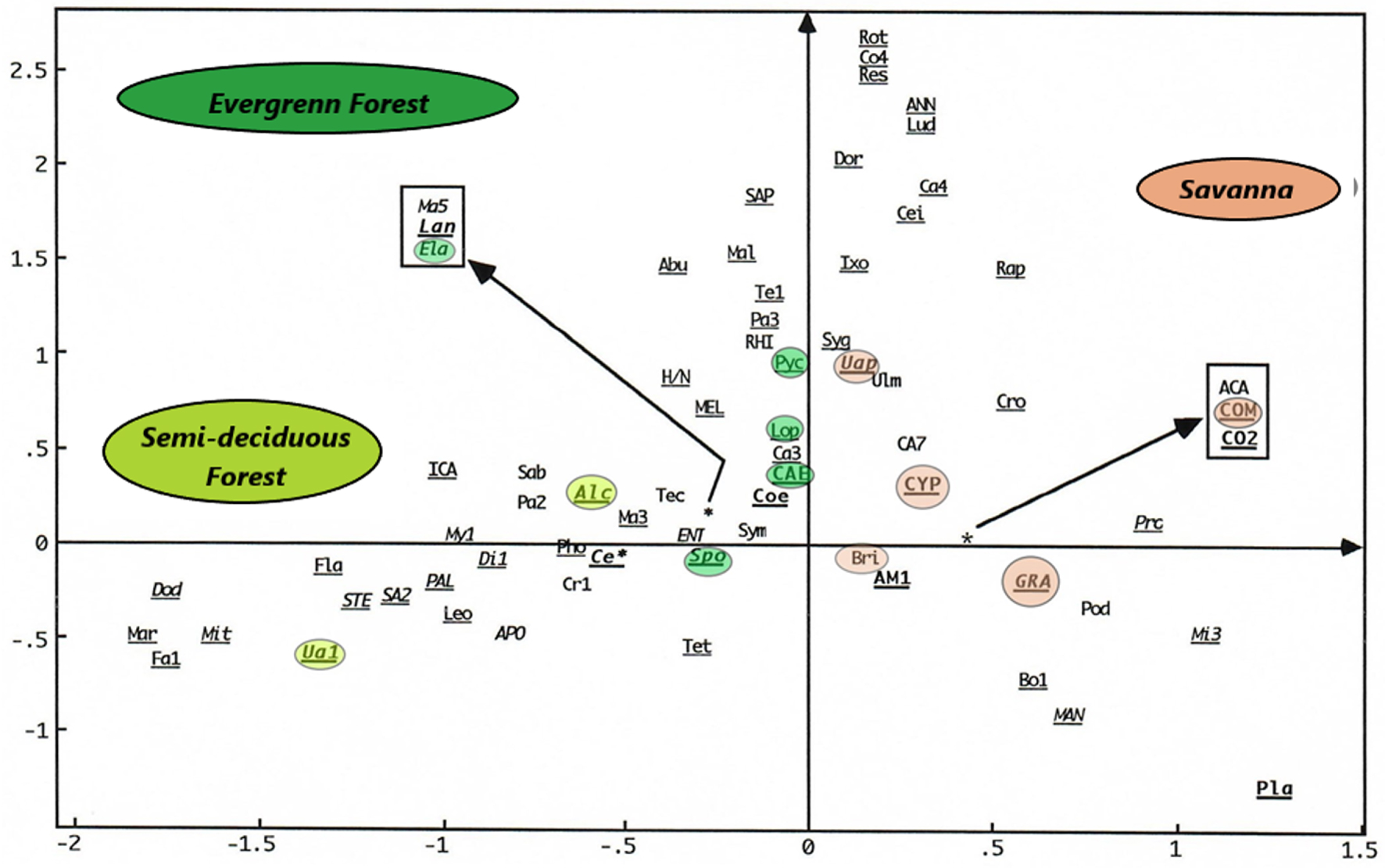

AFC 3: Point cloud of taxa, including those with high contributions and inertias are located on either side of the origin, and correlate the distribution of the samples on axis 1: positive values for savannah, and negative values for forests.

3.2.2. The Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

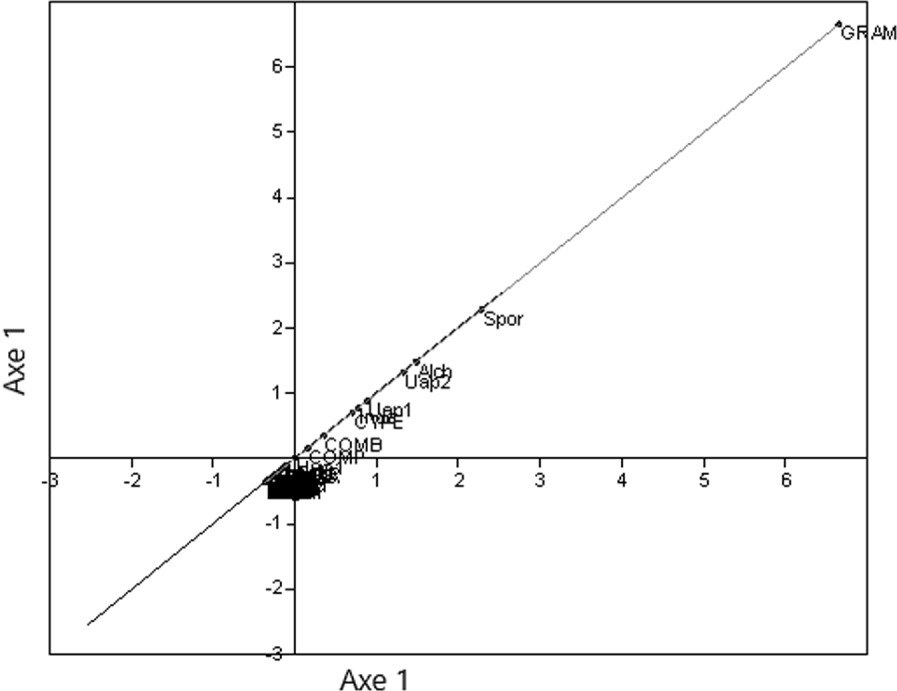

The point cloud on the foreground factor (Figure 7) from a main component analysis (PCA) on the Sanaga Basin samples confirms FCA 2. Almost all taxa are grouped in the centre, except those with high contributions ending up towards the periphery of the ellipsoid of correlations (Graminae, Spores, Alchornea and Uapaca guineensis); as is the case on the diagonal (Figure 8) formed by the factor plane of the PCA where axis 1 is placed on the axis of the abscises and on the axis of the ordained.

PCA (Axis 1, Axis 2) on the reduced matrix with relatively frequent and abundant taxa, characteristic of the different plant ecosystems.

3.3. Pollen spectra

Recurrent taxa, characteristic of different plant ecosystems and highlighted by analysis of statistical data, are shown in Figure 11 showing the evolution in space of pollen spectrum through the Sanaga and Mbam transects.

4. Discussion

4.1. Conformity of the image of the local plant cover in the samples of river banks

Generally for many palynological studies, the authors base their interpretations based solely on analyses of pollen diagrams. Here, the important results of this work and the analysis of pollen spectra were easily supported by the prior use of a multivariate statistical treatment.

The FCA 1 carried out on all 38 samples allowed to obtain on the factor plane the first two axes bringing together the bulk of inertia, a cloud of points around axis 1 of the abscises that discriminates on either side of the origin the samples Sanaga basin from those in coastal basins, particularly samples (4, 16 and 18). The eccentricity of these three samples is due to the over-representation of pollens from Rhizophora, a major taxon of mangroves. Undeniably, the Sanaga group is characterized by the absence of Rhizophora pollens. On the other hand, the identity of the coastal basin sample group, opposed to the Sanaga group, is defined not only by the presence of Rhizophora, but also by other taxa characteristic of the coastal evergreen forest.

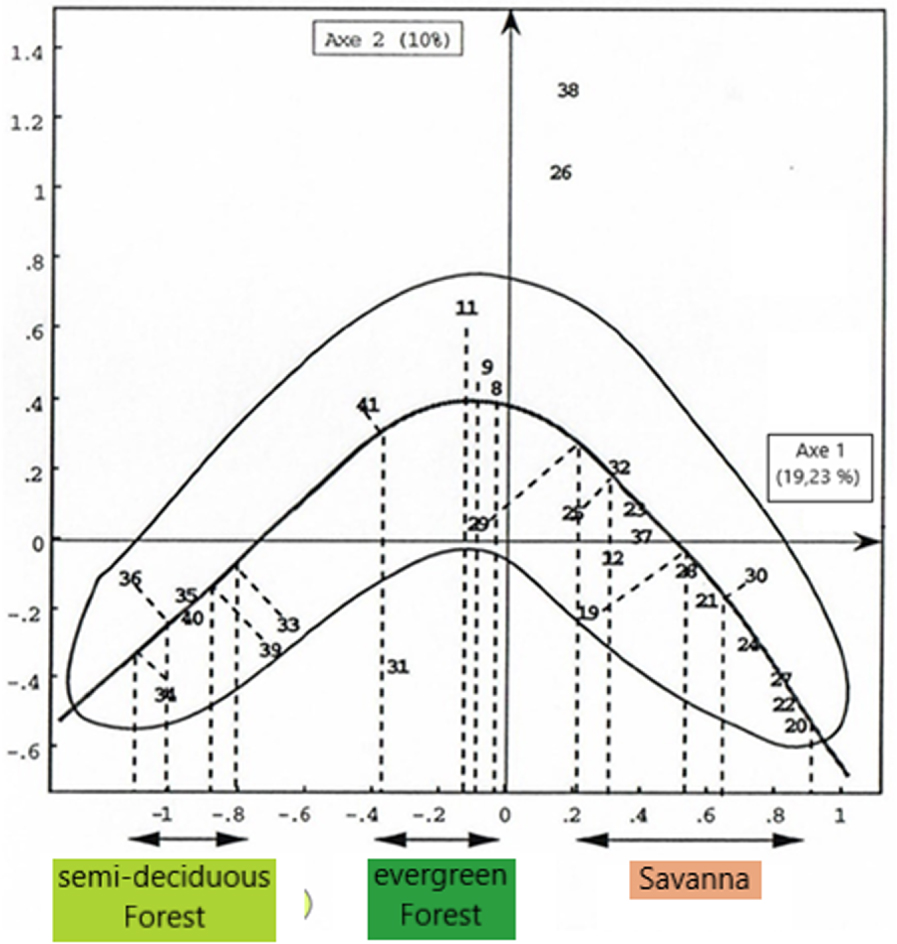

By examining only the 27 samples of the Sanaga Basin in FCA 2 this time, the effect of The Over-representation of Rhizophora is resolved. According to Figure 5 and in relation to axis 1, the samples are arranged on either side of the origin: on the right, the samples of the savannah, and on the left those of the forest. On the other hand, on the forest samples side, axis 2 discriminates above the samples of the evergreen forest, and at the bottom the samples of the semi-deciduous forest. Simultaneous projection or projection on different graphs of point clouds of samples or taxa from the same FCA, in this case FCA 2, shows the taxa that play a great role in the disposal of samples (Figure 6). Such taxa have also been revealed by the PCA (Figure 7), almost all taxa are grouped in the centre, except those with high contributions that are located towards the periphery of the ellipse of correlations (Graminae, spores, Alchornea and Uapaca guineensis). The arrangement of these taxa on the same side of the positive values of the axis shows a “size effect”, since they are the most abundant. These same taxa are aligned on the diagonal formed by axis 1 (Figure 8) that could be considered an ecological indicator.

PCA (Axis 1, Axis 1): Taxa with high contributions and inertia, characteristic of plant ecosystems are far from the origin.

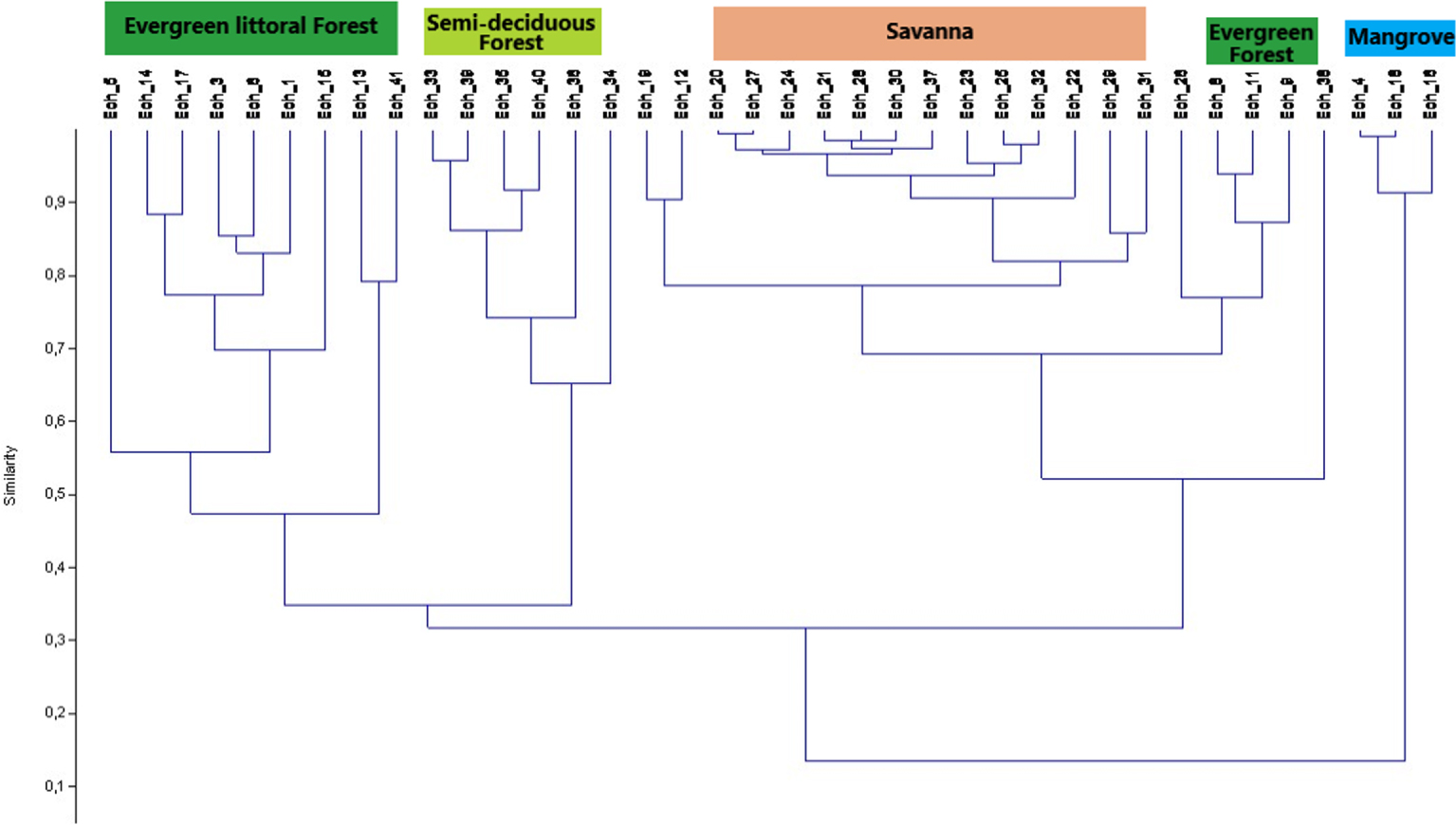

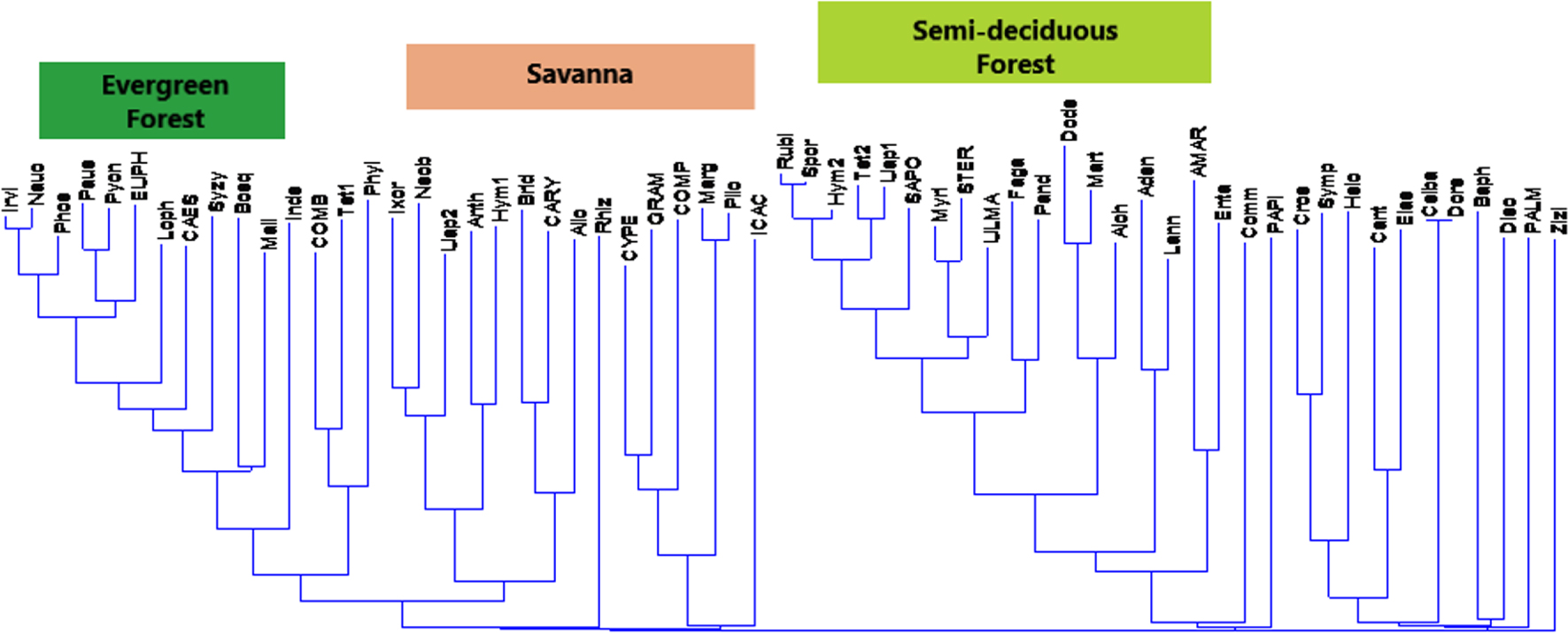

The Dendrogramm analyses applied to the initial matrix and the reduced matrix to the Sanaga basin samples complements the factor analyses in the same direction. According to Figure 9 from a “Clusters analysis” shows that the aggregation levels and the proximity of the samples are not random, they rather come from the affinities provided by the absence, presence or abundance of the associated taxa. Thus, Figure 10 from a “Neighbour joining” correlates the taxa in the disposition of the samples in a Dendogramm hierarchical classification.

Clusters analyses_Mode Paired group/Correlation.

Neighbour joining_Mode Correlation/Final branch on the matrix reduced to 27 samples from the Sanaga basin.

Evolution spectra of taxa characteristic of different ecosystems following the Sanaga and Mbam transects.

From what is done, the factor analyses and the “Cluster analyses” have revealed different ecosystems, namely the savannah, the semi-deciduous forest, the evergreen forest and the mangroves. In summary, savannah samples contain high proportions of Poaceae (Graminae), the omnipresence of Asteraceae (Compositae), Cyperaceae, Bridelia; the semi-deciduous forest is characterized Uapaca guineensis, Elaeis, Myrianthus, the Ulmaceae and the Sapotaceae; the evergreen forest characterized by the taxa of Caesalpiniaceae, Pycnantus, Lophira and Syzygium; and mangroves by Rhizophra, and Pandanus. We note the presence of some ubiquitous taxa such as Alchornea and Spores. If the high pollen values of Alchornea result from the fact that it is a pioneer shrub of forest recruits, while the high proportions of spores are related to the Pteridophytes and Bryophytes that grow abundantly in wetlands [Letouzey 1968].

These multivariate analyses provide further evidence to the numerous palynological studies that link pollen analyses to botanical harvests in the different ecosystems of the surrounding vegetation cover [Bengo 1996, Kimpouni et al. 2014, Lebamba et al. 2009a, Vincens et al. 2000, Youta Happi 1998].

4.2. Characterization of pollen transport from the continent to the ocean (Guttman effect)

The FCA 2 cloud has a parabolic form that generally indicates that the factors of axis 1 and 2, as a matter of linear independent principle, are in fact related to one or more other axes [Benzécri 1980]. For interpreting this unique factor, a projection of the different dots is made on a straight line joining the two ends of the cloud (Figure 12). Samples (8, 9, 11, and 41) of the evergreen forest downstream of the Sanaga are placed in a middle or intermediate position between the savannah sample group and the semi-deciduous forest group. If factor 1 had instead been defined as an ecological indicator of samples, on the other hand axis 2 would be the single factor that would bring together some savannah and semi-deciduous forest taxa in samples further downstream, and this factor could be transport, a phenomenon also observed with the hierarchical classification where the evergreen forest samples are closer to those of the savannah, then geographically it is rather the semi-deciduous forest (Figure 1). This shows that downstream of the Sanaga, samples located in evergreen forest are influenced by the taxa of the semi-deciduous forest and savannah which develop further upstream and are certainly transported there either by water or by wind.

AFC 2: Guttman effect.

To be able to distinguish the dominant mode of transport of pollens on the Cameroonian coasts consists in knowing well the atmospheric circulation of air masses in this region and the suspended solids in water inputs. The monsoon associated with westerly winds forms a permanent flow to the continent that can counter the action of the Harmattan. However, pollens carried by the Harmattan dust were observed on gauze filters installed on ships cruising far off the Gulf of Guinea [Calleja and Van Campo 1990] and on the tops of cores of the West African platform [Dupont and Agwu 1991, Hooghiesmstra et al. 1986]. It seems likely that the Harmattan dusts, which hardly exceed the Forest/Savanna limit and part of the dusts from the dry mist [Suchel 1988], and that the rainfall falls to the ground, are taken up by runoffs that reach the rivers, the Sanaga River and finally the mouth. So, it can be concluded that wind inputs are not significant in the deposits of the Cameroonian coast, which leads us to focus on fluvial inputs.

4.3. Highlighting river transport

The average Poaceae pollen in the ecological niches of the northern savannas is around 43%, and these values are maintained at a level of about 20% in the samples located further downstream. Pycnanthus pollens from the coastal forest and Celtis, Martretia, Tetrorchydium or Elaeis pollens from semi-deciduous forest are found in the samples downstream of the Sanaga, but absent in the samples located further down the savanna. This observation is justified by the simple reason that a river cannot flow and carry these inputs upstream, even the permanent flow of westerly winds is not capable of doing so. Moreover, the damaged pollens, which are difficult to identify because of the deterioration of their walls, are present in abundance in the samples located downstream of the Sanaga, certainly they have been destroyed by a long transport by water. In fact, pollens are probably sedimented several times on the river bed or banks and remobilized at the time of floods before reaching the river mouths. There is thus a differential degradation of pollen. When pollen is observed in ultraviolet light, unevenness in fluorescence is observed, which would indicate differences in alteration due to varying degrees of exposure to light and air during river transport (Personal communication, Poumot “in Bengo [1996]”).

After the deduction of pollen transport by the Guttman effect following the correspondence factor analysis, based on the analysis of pollen spectra of transects, it can therefore be inferred that a good part of the pollen that arrives on the platform of Cameroon is transported by the Sanaga River. This was also observed in dredging samples on the Cameroonian platform where the large proportions of pollen processions were located in the axis of river deposits [Bengo 1996]. Similarly, studies similar to ours have also shown the more or less important role in pollen transport towards the mouth of the Senegal River [Lézine and Edorh 1991], and Trinity River in America [Traverse et al. 1990].

The isotopic study of carbon 13 on the same samples as ours [Bird et al. 1994] gave average values of −19 to −17‰ for upstream Sanaga samples and −27‰ for forest samples. Thus, the values of −25 to −24‰ near the mouth of the Sanaga could therefore be explained by a mixture of organic matter coming from the savannahs by the Mbam and the Sanaga. Once again, the results of the isotopic study converge completely with those of palynology.

5. Conclusions

Pollen trapped in the bank silt quite clearly records the image of the surrounding vegetation cover. The methodology and analyses adopted for this palynological study finally led to highlight the terrigenous origin of sedimentary inputs from the Cameroonian continental shelf and the preponderance of fluvial transport. Multivariate analyses allowed to corroborate the pollen identification, to differentiate and group the samples according to the plant ecosystems where they were taken. The Guttman effect and the Dendogramm hierarchical classification showed that the matching of the different groups of samples was related to a single factor which is pollen transport. Compared to the regional atmospheric circulation, wind transport was found to be negligible, whether it is the Harmattan winds blowing towards the ocean or the trade winds and westerly monsoon winds that are directed towards the mainland. The absence of typical forest taxa downstream in the savanna samples, and the presence of typical savanna taxa upstream in the downstream samples, leads to the conclusion that there is fluvial transport of Graminae and others towards the mouth. Thus, it can be noted that, on the West African coasts, pollen transport by wind is important; whereas, on the southern coasts of the Gulf of Guinea, it is essentially fluvial through the drainage of large basins. These results of pollen dynamics could be transposed to a basin other than that of the Sanaga.

Acknowledgements

For their contributions to the writing of this article, sincere thanks to: Jean de Dieu Nzila, CAMES Lecturer (Marien Ngouabi University); Victor Kimpouni, CAMES Lecturer (Marien Ngouabi University); Noel Watha Doudy, Assistant Master CAMES (Marien Ngouabi University); Anthelme Tsoumou, Doctor (Marien Ngouabi University).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0