1. Introduction

Lanthanides and Y known as Rare Earth Elements (REE) generally occur in the trivalent oxidation state (Ln3+) except Ce (Ce3+ and Ce4+) and Eu (Eu2+ and Eu3+), which display very similar behavior during geochemical processes in a wide range of geological environments [Bau and Dulski 1995; Shannon 1976]. This characteristic of REE have been used as a geochemical indicator for investigation of ore deposits and interpretation of the related geochemical processes during formation of deposits such as fluorite deposits [Abedini et al.2019a; Ackerman 2005; Akgul 2015; Deng et al.2014; Dill et al.2016; Sasmaz and Yavuz 2007; Sasmaz et al.2018; Williams et al.2015]. The lanthanides are a coherent group of elements that their ionic radii gradually decrease with increasing the atomic number from La (1.03 Å) to Lu (0.86 Å), which is known as the lanthanide contraction [Shannon 1976]. These specifications cause them to display similar behaviors and graphically smooth distribution patterns in geochemical investigations indicating their charge and radius controlling characteristic [Bau 1996].

These irregularities have been interpreted as the existence and occurrence of the tetrad effect phenomenon in geochemical processes [Abedini et al.2018a,b,c; Kawabe 1995; Lee et al.2013; Masuda et al.1987; Takahashi et al.2002], which have been reported for the first time by Fidelis and Siekierski [1966]. Lanthanides tetrads are known as four separate groups including La–Nd (first tetrad), Pm–Gd (second tetrad), Gd–Ho (third tetrad) and Er–Lu (fourth tetrad) correspond to 1∕4, 1∕2, 3∕4 and filled electrons of 4f orbital in lanthanide elements [Jahn et al.2001]. As can be seen, Gd is a common element between second and third tetrads. The tetrad effect is another factor that controls the REE distribution beside other ones such as pH of fluids/solutions, scavenging, mineral phases and stability of REE-complex [McLennan 1994; Sasmaz et al.2005; Veksler et al.2005].

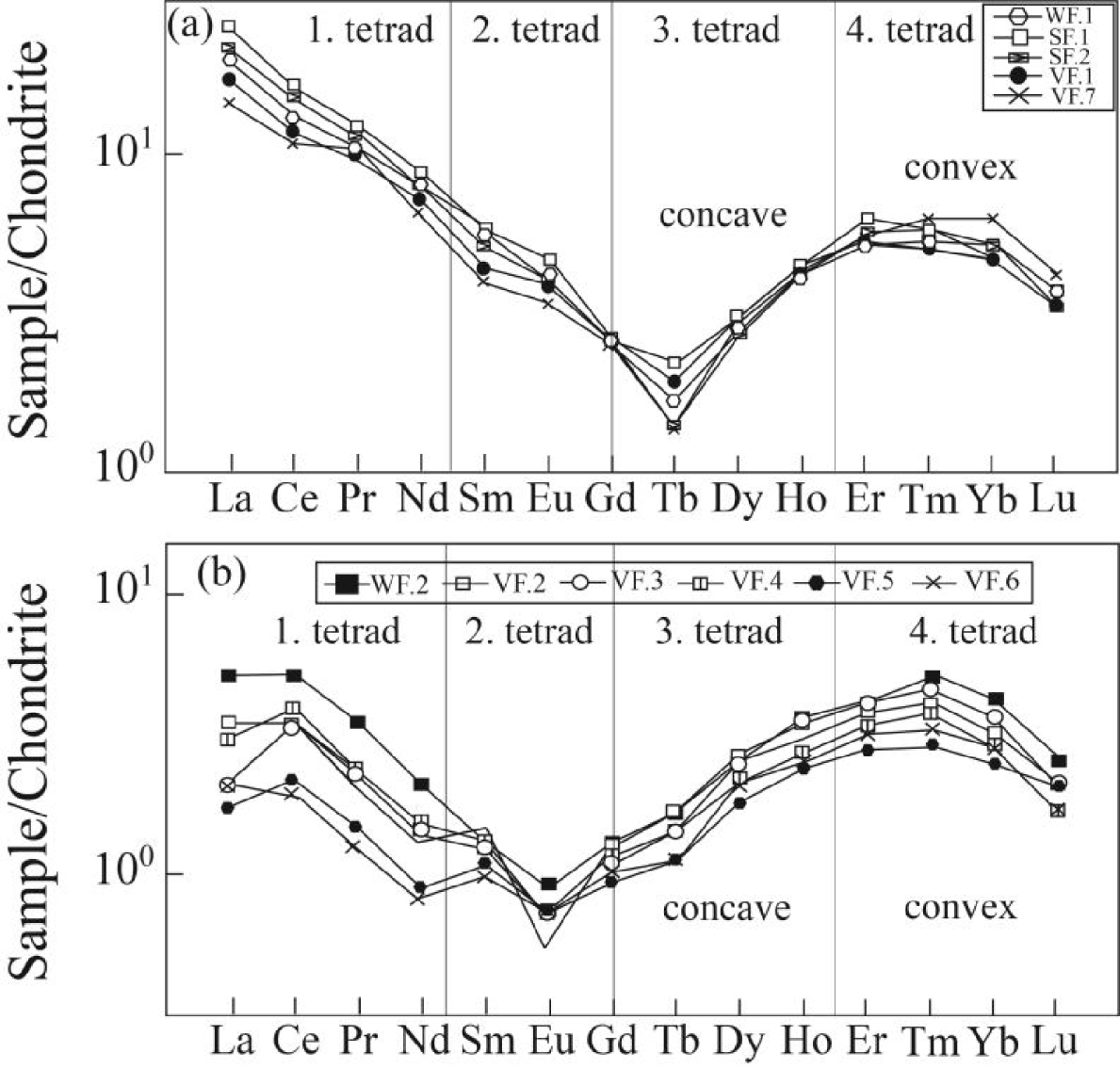

Based on the recent works, the form of tetrad effect-bearing normalized REE curves can be categorized into four groups [Abedini and Rezaei Azizi 2019; Abedini et al.2019b; Feng et al.2014; Minamim et al.1998; Nardi et al.2012]: (1) concave or W-type indicative for low temperature deposits, (2) convex or M-type generally occur in magmatic or related systems, (3) conjugate convex–concave or W–M-type and finally (4) zigzag pattern, which can be related to incomplete occurrence of tetrad effect. Previous studies have proposed some quantum mechanical based mechanisms for the occurrence of tetrad effect such as nephelauxetic ratios, the spin energy for coupling, electron configuration of lanthanides and Gibbs free energy [Jorgensen 1970; Kawabe et al.1999; Masuda et al.1994; Nugent 1970].

Fluorite deposits in Iran reach to 30 with being more than 3.4 million tones reserve. Some on these deposits are situated on the Sanandaj-Sirjan metamorphic belt including Qahr Abad, Bagher Abad, Darreh Badem, Atash Kuh and Laal-Kan [Alipour et al.2015; Ehya 2012; Rezaei Azizi et al.2018b]. In this paper we focused on the behavior of the REE and some trace elements with emphasizes on the occurrence of tetrad effect in fluorite samples to constrain the difference between early and late stage fluorite precipitation in the hydrothermal fluorite deposit of the Laal-Kan district.

2. Geological settings

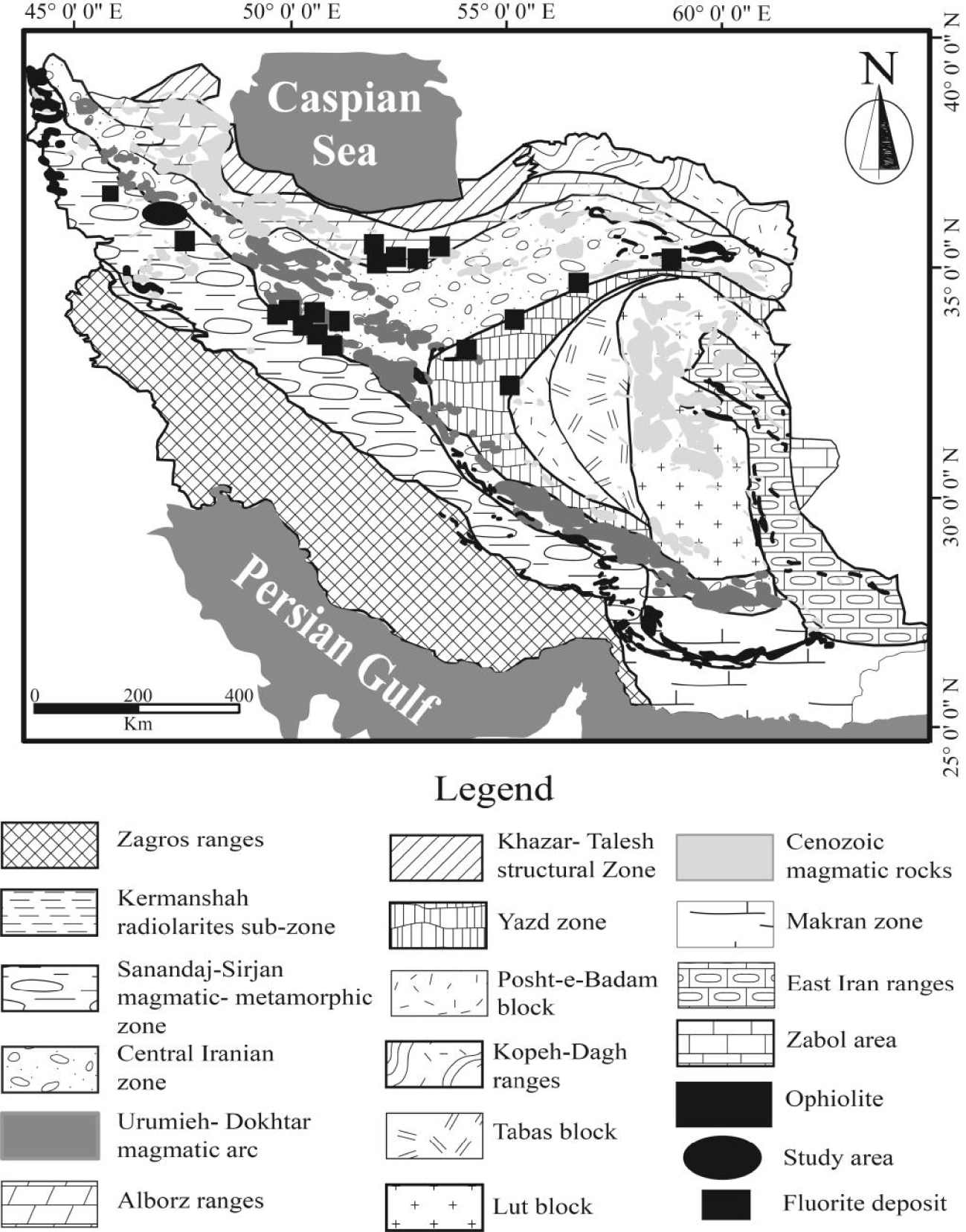

Previous studies indicated that many Zn–Pb and fluorite-barite deposits have been formed at the margins of the Central Iranian Zone [Rajabi et al.2012]. Based on the structural geology map of Iran [Aghanabati 1998; Alavi 1991], the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit is situated ∼90 km west of Zanjan city, NW Iran at the contact zone of the Sanandaj-Sirjan metamorphic belt and Urmia-Dokhtar magmatic arc [Gilg et al.2006; Richards et al.2006] and a worldwide known Zn–Pb Angouran mine is located ∼500 m south of the fluorite deposit (Figure 1).

Simplified structural map of Iran [Alavi 1991; Aghanabati 1998] indicating the location of Laal-Kan and some fluorite deposits.

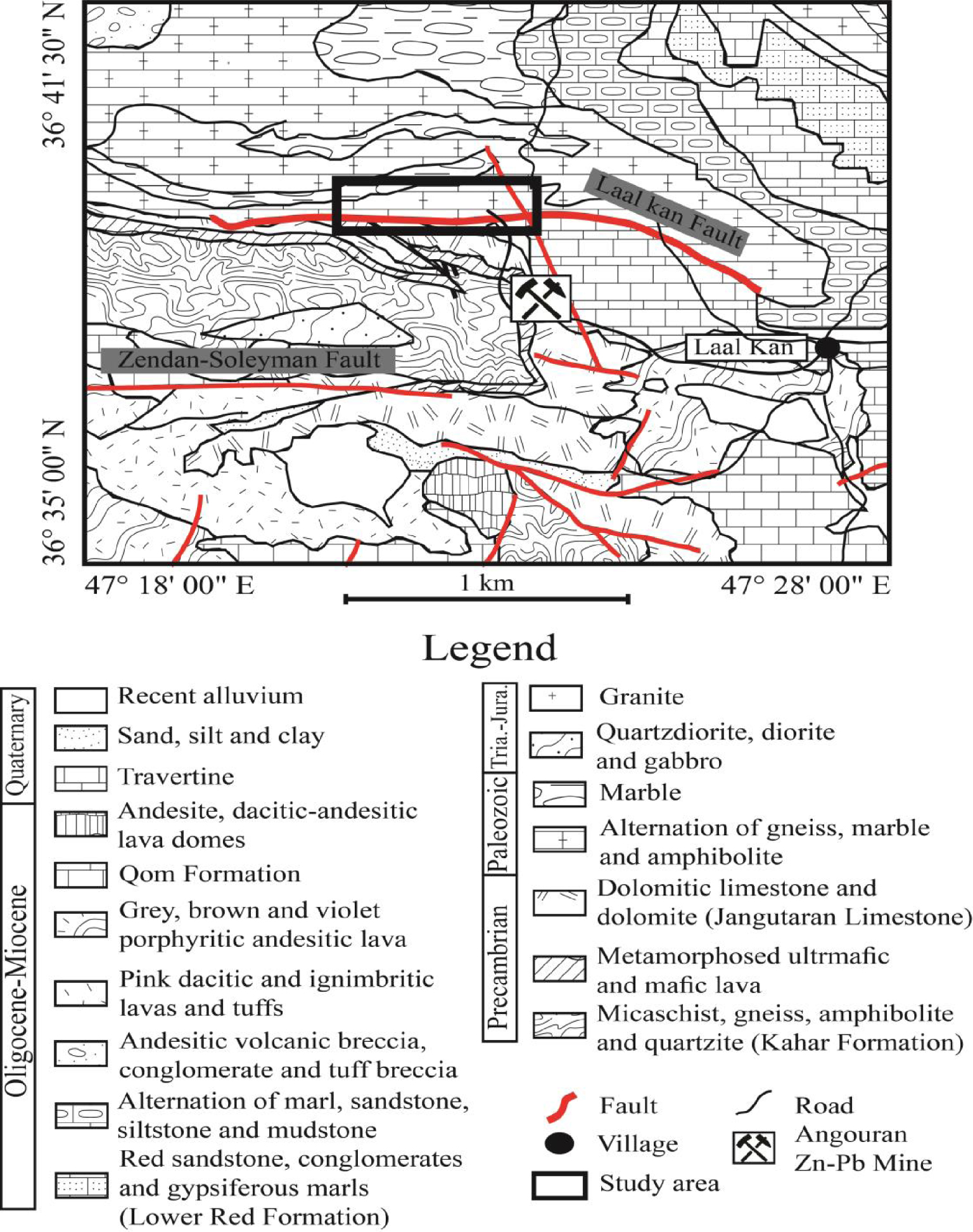

The simplified geology map of the study district (Figure 2) shows that diverse lithologies from the Precambrian to Quaternary ages crop out in this district [Babakhani and Ghalamghash 1990]. These lithologies from oldest to youngest can be summarized as follows: (1) the Kahar Formation including micaschist, gneiss, amphibolite and quartzite of the Neoproterozoic age, (2) a metamorphosed ultramafic–mafic lava and dolomitic limestone–limestone (Jangutaran Limestone) of the Precambrian age, (3) a highly metamorphosed alternation of schist, gneiss, marble and amphibolite of the Paleozoic age, (4) quartzdiorite, diorite, gabbro and granite of the Triassic–Jurassic age, (5) the Lower Red Formation including sandstone, conglomerate and gypsiferous marls of the Oligocene–Miocene age, (6) alternation of marl, sandstone, siltstone and mudstone of the Oligocene–Miocene age, (7) andesitic volcanic breccia of the Oligocene–Miocene age, (8) dacitic-ignibritic lavas and porphyritic andesitic lavas of the Oligocene–Miocene age, (9) limestone of Qom Formation of the Oligocene–Miocene age, (10) andesitic, dacitic-andesitic lava domes of the Oligocene–Miocene age, (11) travertine, sand, clay and recent alluvium of the Quaternary age.

Simplified geology map of the study district (after Babakhani and Ghalamghash [1990]).

Field observations reveal that fluorite mineralization in the form of open-space fillings, veins and veinlets are in the contact zone between the highly metamorphosed schist, gneiss, amphibolite of Paleozoic age and the Jangutaran limestone of the Precambrian age [Rezaei Azizi et al.2018b]), which deposited along and/or parallel to the Laal-Kan Fault in a W-E trending (Figure 2). The existence of a close relationship between the fault system and mineralization emphasizes that the structural systems have played a significant role as pathways for uprising hydrothermal fluids [Rezaei Azizi et al.2018b]. Fluorite mineralization in this deposit has a variable thickness from a few centimeters to ∼4 m. Field observations indicate that the contact between mineralization and host rocks are relatively sharp with no significant alteration. White, smoky and violet colors are the most abundant that can be seen in the study district.

3. Sampling and analytical methods

Thirty-seven samples of fluorite in white, smoky and violet colors from the excavated places of the deposit were collected for petrographic studies. In order to prevent any probable alteration and/or wall-rock interaction during our studies, fifteen thin sections of fluorite samples (in all available colors) were prepared and studied using a petrographic microscope in the Geology Department at Urmia University to determine the available mineral phases and their genetic relationship.

For chemical analysis, to prevent any contamination all fluorite grains were separated from the host rocks by handpicking under a binocular microscope in the Geology Department at Urmia University. Totally, eleven fluorite samples (>99% purity) of the study district in various colors including white (#2), smoky (#2) and violet (#7) were analyzed using the inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) technique to determine the trace and REE concentration at the Zarazma Zangan Iranian Co, Iran.

For chemical analysis, all the prepared samples were crushed to less than −80 mesh after drying at a temperature less than 60 °C. 250 g of fluorite samples were powdered to less than −150 mesh using a steel ring mill and 0.2 g of these prepared fluorite samples were weighted. 1.5 g lithium borate (Li2B4O7) was added to each of the fluorite samples and heated at 980 °C for ∼30 min. After cooling these samples, each one of them was dissolved in 100 ml nitric acid (5%). For measuring the amount of trace and REE in each samples, they poured into a Polypropylene Test Tube. Measuring the loss on ignition (LOI) was calculated by the amount of weight loss of 1 g sample before and after heating at 950 °C for ∼90 min. The calibration and standards were also carried out to control during analysis processes. The detection limits for analyzed elements including trace and REE varied from 0.02 to 5 ppm.

4. Results

4.1. Petrography

The mineralogy studies in the fluorite samples of this district showed that fluorite, quartz and Fe-oxides mostly hematite were the major mineral phases of the samples but, barite, calcite, hemimorphite and clays were distinguished as the minor mineral phases.

Based on the field observations, fluorite mineralization in the form of open-space fillings, veins and veinlets consisting of relatively coarse-grained and massive crystals, which display relatively sharp contact with schist (host rock). Hemimorphite and Fe-oxides are relatively abundant minor mineral phases that can be distinguished in the supergene zone due to weathering.

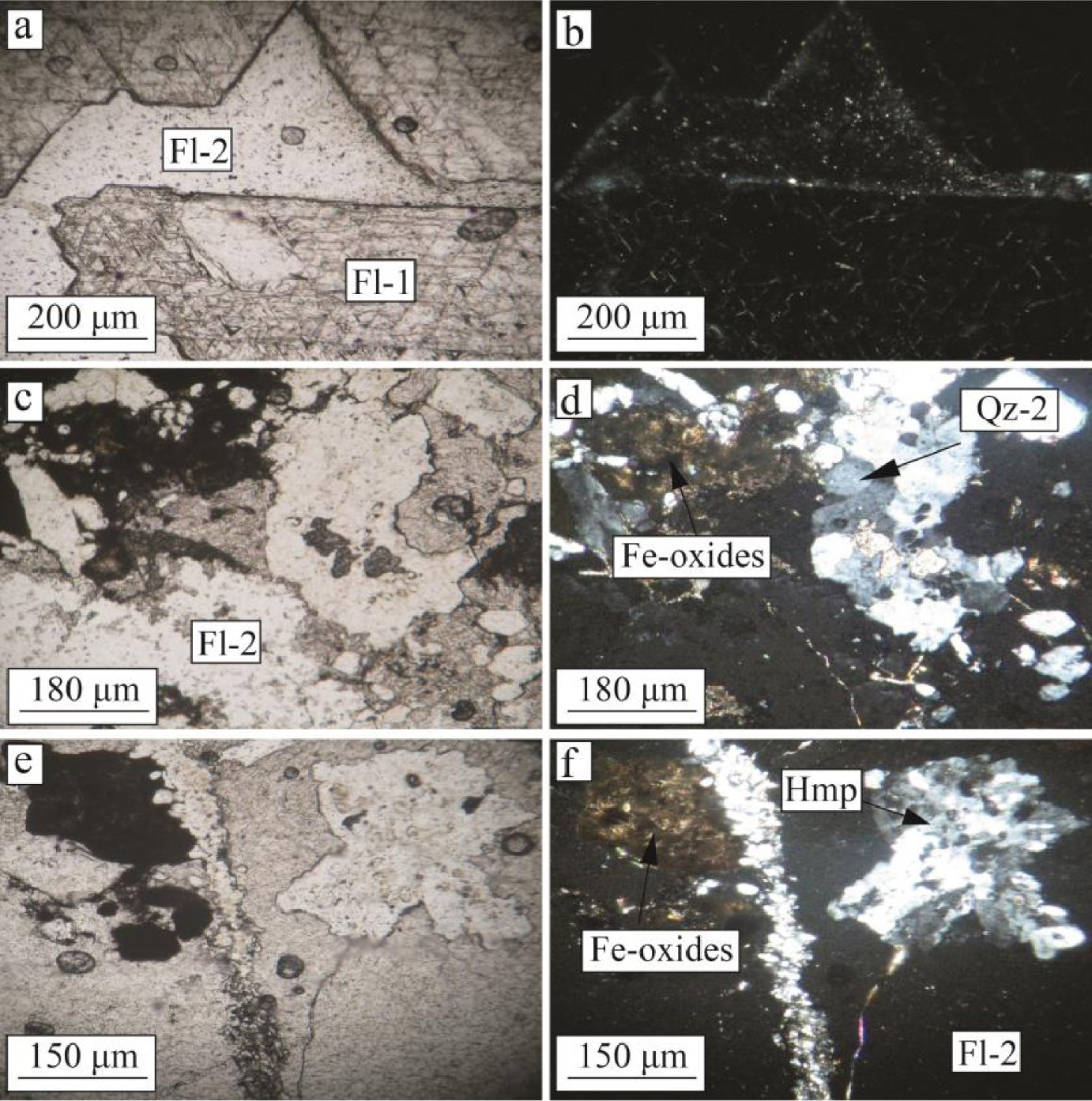

The studies indicate that fluorite mineralization has been probably formed in two different stages. Early stage fluorite crystals are characterized by large coarse-grained and massive euhedral to subhedral crystals (Figure 3a, b). These studies also indicated that tectonic activities caused micro fractures to be formed in the early stage fluorite crystals. These fractures were filled with Fe-oxides and clay mineral phases during weathering processes (Figure 3c, d). The early stage fluorite crystals were also associated with first generation euhedral to subhedral quartz (Figure 3e, f). The late stage fluorite is characterized by subhedral to anhedral, fine-grained fluorite crystals, which were formed in the fractures of the early stage fluorite crystals and/or schist (host rock) at distance some far from the open-space filling and cavities in the study district (Figure 4a, b). The late stage fluorite in this district is associated with subhedral to anhedral fine-grained quartz (Figure 4c, d) and hemimorphite (Figure 4e, f).

Photomicrographs of the early stage fluorite mineralization in the Laal-Kan deposit. (a) and (b) coarse-grained and massive early stage fluorite (Fl-1) filled with Fe-oxides and clay minerals under ppl and xpl lights, respectively. (c) and (d) the occurrence of micro fractures in the early stage fluorites (Fl-1) filled with quartz and calcite under ppl and xpl lights, respectively. (e) and (f) first generation euhedral to subhedral quartz (Qz-1) crystals in the early stage fluorite Fl-1) under ppl and xpl lights, respectively. Fl = fluorite and Qz = quartz. Abbreviations are from Whitney and Evans [2010].

Photomicrographs of the late stage fluorite mineralization in the Laal-Kan deposit. (a) and (b) coarse-grained and massive early stage fluorite (Fl-1) and late stage fluorite (Fl-2) under ppl and xpl lights, respectively. (c) and (d) Fe-oxides and subhedral to anhedral fine-grained quartz associated with the late stage fluorites (Fl-2) under ppl and xpl lights, respectively. (e) and (f) hemimorphite in association with the late stage fluorite (Fl-2) under ppl and xpl lights, respectively. Fl = fluorite, Hmp = hemimorphite and Qz = quartz. Abbreviations are from Whitney and Evans [2010].

4.2. Geochemistry

The concentrations of some trace and REE for fluorite samples in the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit are presented in Table 1. As shown in this table, the concentration of Y, Hf and Zr vary between 6.1–8.3, 0.65–1.61 and 0.8–4.7 ppm, respectively. The total REE values of the analyzed samples also vary in the range of 4.16–25.67 ppm. Table 2 also lists the calculated geochemical ratios for fluorite samples in the study district. The Zr/Hf ratio is in the range of 0.5–4.75. The Y/Ho and La/Ho ratio values for fluorite samples vary from 24.4 to 52.31 and from 2.88 to 24.92, respectively.

The concentration values (in ppm) of some trace and REE for fluorite samples in the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit

| Element | White fluorite | Smoky fluorite | Violet fluorite | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF.1 | WF.2 | SF.1 | SF.2 | VF.1 | VF.2 | VF.3 | VF.4 | VF.5 | VF.6 | VF.7 | |

| Fl-1 | Fl-2 | Fl-1 | Fl-1 | Fl-1 | Fl-2 | Fl-2 | Fl-2 | Fl-2 | Fl-2 | Fl-1 | |

| Y | 6.7 | 8.3 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.1 |

| Hf | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 1.34 | 1.58 | 1.61 | 1.48 | 1.39 | 1.17 | 0.83 |

| Zr | 3.8 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 3.6 |

| La | 4.72 | 1.2 | 5.98 | 5.1 | 4.04 | 0.82 | 0.49 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.48 | 3.45 |

| Ce | 7.89 | 3.08 | 10.06 | 9.11 | 7.07 | 2.04 | 2.08 | 2.39 | 1.3 | 1.15 | 6.51 |

| Pr | 0.93 | 0.31 | 1.09 | 1.02 | 0.86 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.9 |

| Nd | 3.58 | 0.95 | 3.98 | 3.65 | 3.25 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.4 | 0.36 | 2.98 |

| Sm | 0.87 | 0.19 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.59 |

| Eu | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| Gd | 0.53 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.2 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.49 |

| Tb | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Dy | 0.72 | 0.6 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.66 |

| Ho | 0.26 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.25 |

| Er | 0.84 | 0.65 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.6 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.5 | 0.89 |

| Tm | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| Yb | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.4 | 0.46 | 1.02 |

| Lu | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.1 |

| ΣREE | 21.6 | 8.41 | 25.67 | 23.27 | 19.5 | 6.36 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 4.16 | 4.25 | 18.23 |

Fl-1 = early stage fluorite and Fl-2 = late stage fluorite.

The calculated geochemical ratios (mass ratios) for fluorite samples in the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit

| Ratios | White fluorite | Smoky fluorite | Violet fluorite | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF.1 | WF.2 | SF.1 | SF.2 | VF.1 | VF.2 | VF.3 | VF.4 | VF.5 | VF.6 | VF.7 | |

| Zr/Hf | 4.75 | 2.31 | 4.49 | 4.23 | 3.51 | 1.14 | 0.50 | 1.42 | 0.65 | 1.37 | 4.34 |

| Y/Ho | 25.77 | 27.08 | 36.09 | 29.09 | 24.40 | 28.00 | 34.74 | 39.41 | 48.00 | 52.31 | 48.57 |

| La/Ho | 18.15 | 24.92 | 22.17 | 18.36 | 13.80 | 6.00 | 4.32 | 2.88 | 4.67 | 3.08 | 3.43 |

5. Discussion

5.1. REE geochemistry

REE distribution during geochemical processes is strongly dependent on some paleo physic-chemical conditions such as pH, Eh, temperature of fluids/solutions, fugacity of oxygen in the environment, water/rock interaction and REE-complex stability [Abedini et al.2011; Bau et al.2003; Castorina et al.2008; Khosravi et al.2017; Levresse et al.2011; Nkoumbou et al.2017; Rezaei Azizi et al.2018a; Sasmaz et al.2005; Tassongwa et al.2017]. Fluorite as an informative mineral has been reported from a wide range of deposits and geological environments that can be used to constraint the paleo physic-chemical condition during geochemical investigations [Coşanay et al.2017; Schwinn and Markl 2005].

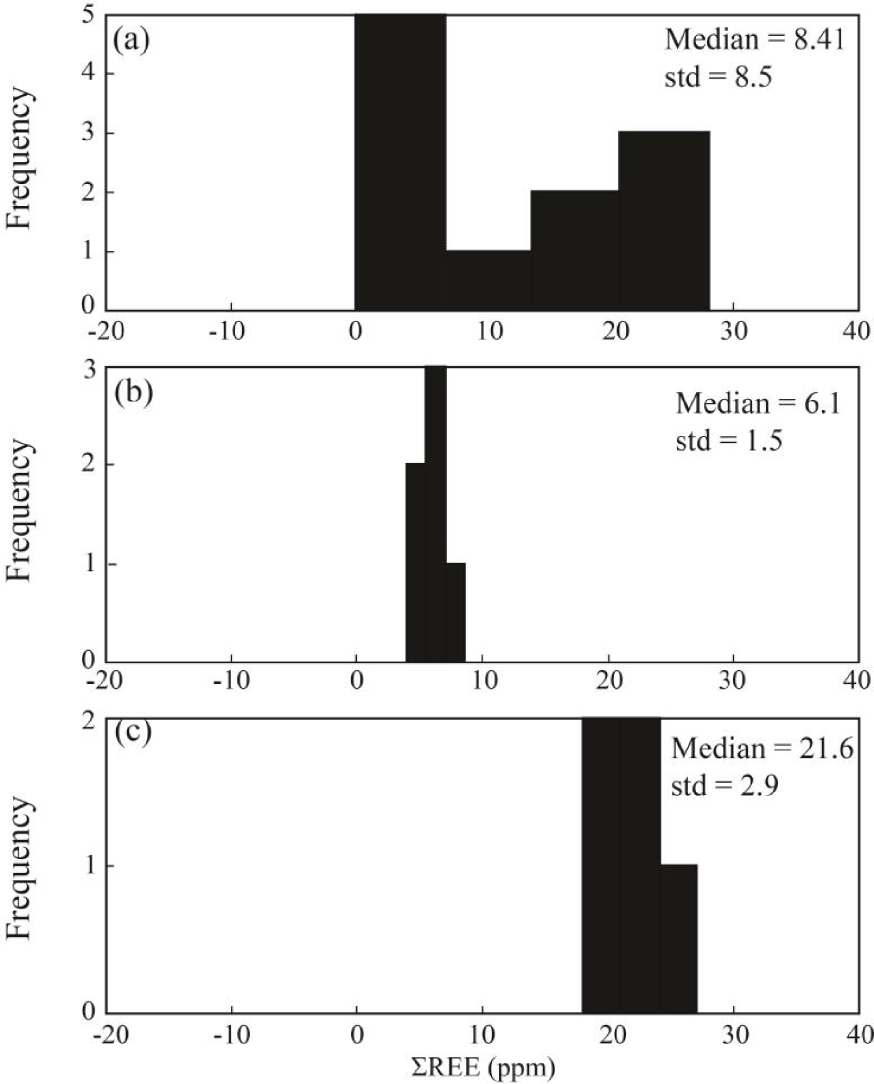

Statistically, the median values of REE concentration in fluorite samples of the study district is 8.41 ppm with the standard deviation equal to 8.5 ppm. The large value for calculated values of the standard deviation means that the distribution pattern for ΣREE in fluorite samples is not a normal distribution [Edjabou et al.2017]. As shown in Figure 5a, the distribution patterns show two different peaks that can be related to different populations due to changes in geochemical condition during formation of fluorite [Abedini and Rezaei Azizi 2019; Badel et al.2011]. The clusters were classified into two populations due to geological, geochemical and mathematical based relationships (Figure 5b, c). The first population includes the fluorite samples that are characterized by low ΣREE with the median and standard deviation values equal to 6.1 and 1.5 ppm, respectively. The second group of samples has larger values of the median and standard deviation values equal to 21.6 and 2.9 ppm, respectively.

The frequency diagrams for ΣREE (ppm) in fluorite samples in the Laal-Kan district. (a) ΣREE, (b) first population of ΣREE (Fl-1) and (c) second population (Fl-2) of ΣREE.

5.2. Tetrad effect

The chondrite-normalized REE patterns for fluorite samples are shown in Figure 6. Previous studies have shown that the early stage fluorite mineralization (Figure 6a) is characterized by LREE enrichment relative to HREE, whereas the late stage ones (Figure 6b) are characterized by LREE depletion [Rezaei Azizi et al.2018b]. The remarkable point in these patterns is the occurrence of the tetrad effect in the fluorite samples of the Laal-Kan deposit. Both early and late stage fluorite samples display a convex form in the chondrite-normalized REE patterns. In this paper, the values of tetrad effect in each group were calculated by (1) proposed by Monecke et al. [2002].

| (1) |

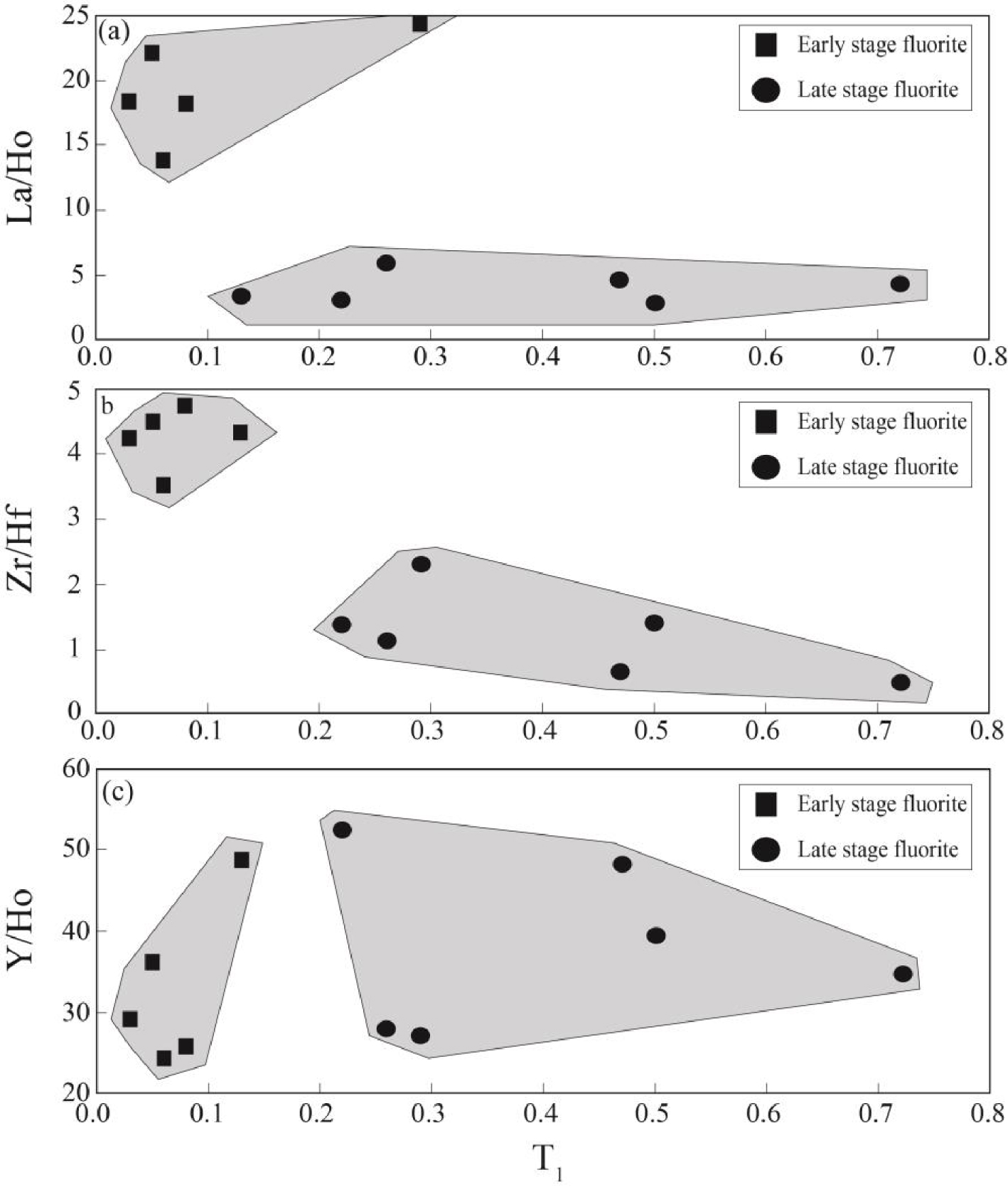

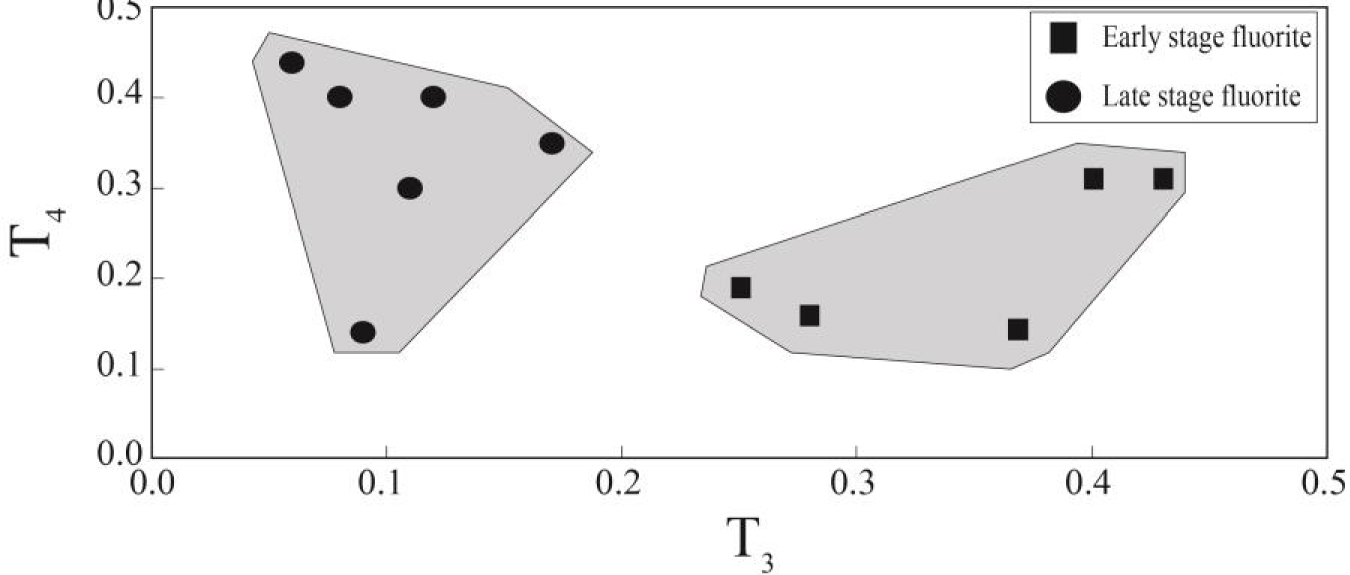

In this equation, XBi and XCi are the concentrations of the two central elements of the individual tetrad, and XAi and XDi the concentrations of the first and the fourth lanthanides of the same tetrad, respectively and Ti (i = 1–4) gives the values for each tetrad. If all tetrad elements are in the straight line Ti will be equal to zero and Ti values higher than zero indicate the occurrence of tetrad effect in the normalized curves. It is worth noting that radioactive Pm does not occur in geological environments, therefore the calculation of second tetrad is impossible [McLennan 1994]. Table 3 lists the calculated values for individual tetrad in fluorite samples of the study deposit. According to these results, the early stage fluorite samples are characterized by low T1, high T3 and low T4 values, whereas in the late stage fluorite samples T1, T3 and T4 values are high, low and high, respectively. Figures 7 illustrate the bivariate diagrams of tetrad effect values in the fluorite samples. As shown in these figures, first tetrad has negative correlation versus third tetrad values (Figure 7a). These trends can be seen in both first versus fourth and third versus fourth tetrad effect values in these samples (Figure 7b, c).

The chondrite-normalized REE patterns for fluorite samples indicating the tetrad fields in the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit. (a) the early stage fluorite samples and (b) the late stage fluorite samples. Normalization values are from Anders and Grevesse [1989].

The bivariate diagrams for the calculated tetrad effect values in fluorite samples of the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit. (a) T1 versus T3, (b) T1 versus T4 and (c) T3 versus T4.

The calculated values for individual tetrad in fluorite samples of the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit

| Values | White fluorite | Smoky fluorite | Violet fluorite | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF.1 | WF.2 | SF.1 | SF.2 | VF.1 | VF.2 | VF.3 | VF.4 | VF.5 | VF.6 | VF.7 | |

| T1 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| T3 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.43 |

| T4 | 0.16 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.31 |

5.3. Mechanism for the occurrence of tetrad effect

Based on the previous researches, the most significant geochemical mechanism for the occurrence of the tetrad effect in various deposits can be categorized as follows [Abedini et al.2017; Badanina et al.2010; Cao et al.2013; Irber 1999; Kawabe 1995; Monecke et al.2007; Nardi et al.2012; Pan 1997; Rezaei Azizi et al.2017]: (1) mineral phase fraction during emplacement of an igneous system, (2) the presence of F-complex in fluid/solution, (3) interaction of fluid and melt in the hydrothermal system and (4) alteration processes including hydrothermal and/or weathering.

The fractionation of mineral phases in igneous systems and interaction of the hydrothermal fluids with host rocks during uprising can generate a remarkable convex (M-type) tetrad effect phenomenon in the separated mineral phases of system [Lee et al.2013; McLennan 1994; Wu et al.2011]. As shown in Figure 6, the chondrite-normalized REE patterns in this deposit have a pronounced convex (M-type) tetrad effect, especially in the third and fourth tetrads. Petrographic and mineralogy studies indicate that the lack of mineral phases such as garnet, monazite and apatite in the fluorite samples of the study district cannot be likely responsible for the occurrence of convex tetrad effect [McLennan 1994; Pan 1997].

Figure 8 illustrates the correlation between T1 tetrad effect values in fluorite samples and some geochemical ratios. As shown in Figure 8a, the early stage fluorite samples are characterized by relatively low T1 tetrad effect values and high La/Ho ratios, whereas T1 tetrad effect values display a high/wide range and very low La/Ho ratios that can be due to fractionation of LREE during hydrothermal fluids migration [Bau and Dulski 1995; Coşanay et al.2017]. Meanwhile, the bivariate diagram of T1 tetrad effect values versus Zr/Hf ratios in the studied samples (Figure 8b) indicate that early stage fluorite samples have relatively positive correlation, but the late stage ones have negative correlation. This means that relatively low pH hydrothermal fluids were likely played important role during precipitation of early stage ones and high pH hydrothermal fluids were probably responsible for precipitation of the late stage ones due to interaction of acidic fluids with carbonate host rocks during the migration of fluids [Rezaei Azizi et al.2018b].

The bivariate diagrams of T1 tetrad effect values for fluorite samples versus (a) La/Ho, (b) Zr/Hf and Y/Ho ratios in the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit.

The Y/Ho ratios in the studied samples display wide ranges from chondoritic to superchondritic (Figure 8c). The higher Y/Ho ratios in fluorite mineral is an indicative of the role of the existence of ligands such as F-, , , Cl-, OH-, and in hydrothermal fluids [Migdisov et al.2016]. During fluorite mineralization, F-rich hydrothermal fluids cause the higher Y/Ho ratio fluorite, but carbonate-rich fluids cause low Y/Ho ratio fluorite to be precipitated [Bühn et al.2003]. The fluid inclusions studies in this district revealed that the composition of hydrothermal fluids were relatively constant during both the early and late stage fluorite [Rezaei Azizi et al.2018b]. This means that REE-complex in the presence of F and carbonate ligands were likely responsible for the occurrence of tetrad effect in the fluorite precipitation. Figure 9 shows the T3 versus T4 tetrad effect values for fluorite samples in the Laal-Kan deposits. As shown in this figure the early and late stage fluorite samples are also seen in two different and separate fields. The early stage fluorite samples are characterized by high T3 values but, the late stage ones with low T3 values. These parameters indicate that the REE distributions in fluorite were probably controlled by tetrad effect phenomenon in this district. Therefore, it can be deduced that the tetrad effect values in fluorite mineralization can be used as a good and powerful geochemical indicator to interpret the physic-chemical conditions and geochemical processes in these types of deposits.

The bivariate dagram of T3 versu T4 tetrad effect values for fluorite samples in the Laal-Kan district.

6. Conclusions

Based on the petrographic studies, chemical analysis, the calculated values of first, third and fourth tetrad, REE behavior, Y/Ho, Zr/Hf and La/Ho ratios in the fluorites of the Laal-Kan fluorite deposit, the conclusions can be summarized as follows:

(1) The petrographic studies indicate that fluorite mineralization have been likely occurred in two different stages including early stage fluorite and late stage ones, which are characterized by coarse-grained/massive and fine-grained crystals, respectively.

(2) The chondrite-normalized REE distribution curves of the fluorite samples display a remarkable convex (M-type) tetrad effect curvatures, which is an indicative of hydrothermal/igneous origin in fluids responsible for fluorite precipitations.

(3) Based on the relationship between tetrad effect values and some geochemical ratios such as La/Ho, Y/Ho and Zr/Hf it can be concluded that interaction between hydrothermal fluids and carbonate host rocks and REE-F complex were likely the main mechanisms for the occurrence of tetrad effect phenomenon in the study district.

(4) The correlations between T1, T3 and T4 tetrad effect values of the fluorite samples with geochemical parameters and previous data of fluid inclusions support the idea that fluorite mineralization in this deposit were probably formed from a fluids with relatively constant composition in different stages.

(5) The separation of early and late stage fluorite samples in the bivariate diagrams such as T1, T3 and T4 versus La/Ho, Y/Ho and Zr/Hf can be used a good and powerful geochemical indicator to investigate and interpret the geochemical processes during deposition of fluorite.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially fully supported by the Bureau of Deputy of Research and Complementary Education of Urmia University. We would like to state our thanks and appreciation to the authorities of this bureau. Our gratitude is further expressed to Professor Vincent Courtillot, Dr. Marguerite Godard, and two other anonymous reviewers for reviewing our manuscript and making critical comments and valuable suggestions which have definitely improved the quality of this work.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0