1. Introduction

A huge body of published works [e.g. see the bibliography in Cordier et al. 2017] suggests that the formation of river terraces, defined as flat surfaces above fluvial sediment, is affected by climate. It has been demonstrated that, in general, river incision took place at climatic transitions [e.g. Vandenberghe 2003, 2015; Bridgland and Westaway 2008; Antoine et al. 2016]. Nonetheless, numerous studies show that terraces are not a simple climatic proxy [Cordier et al. 2017; Schanz et al. 2018; Pazzaglia 2022] and numerous processes interact together in terrace formation [Starkel 1994; Vandenberghe 2003, 2015]. Furthermore, it has been stressed that climatic variations must cross thresholds of duration or magnitude to induce changes between erosion and deposition [e.g. Schumm 1979; Vandenberghe 2003]. The role of the succession of the glacial/interglacial periods is classically described for major fluctuations at 105 years scale [e.g. Starkel 1994; Riser 1999]. However, the role of shorter time scale climatic fluctuations is frequently discussed from the compilation of geochronologic studies distributed on very large areas [Pazzaglia 2022] but is usually poorly evidenced along single rivers [Woodward et al. 2008].

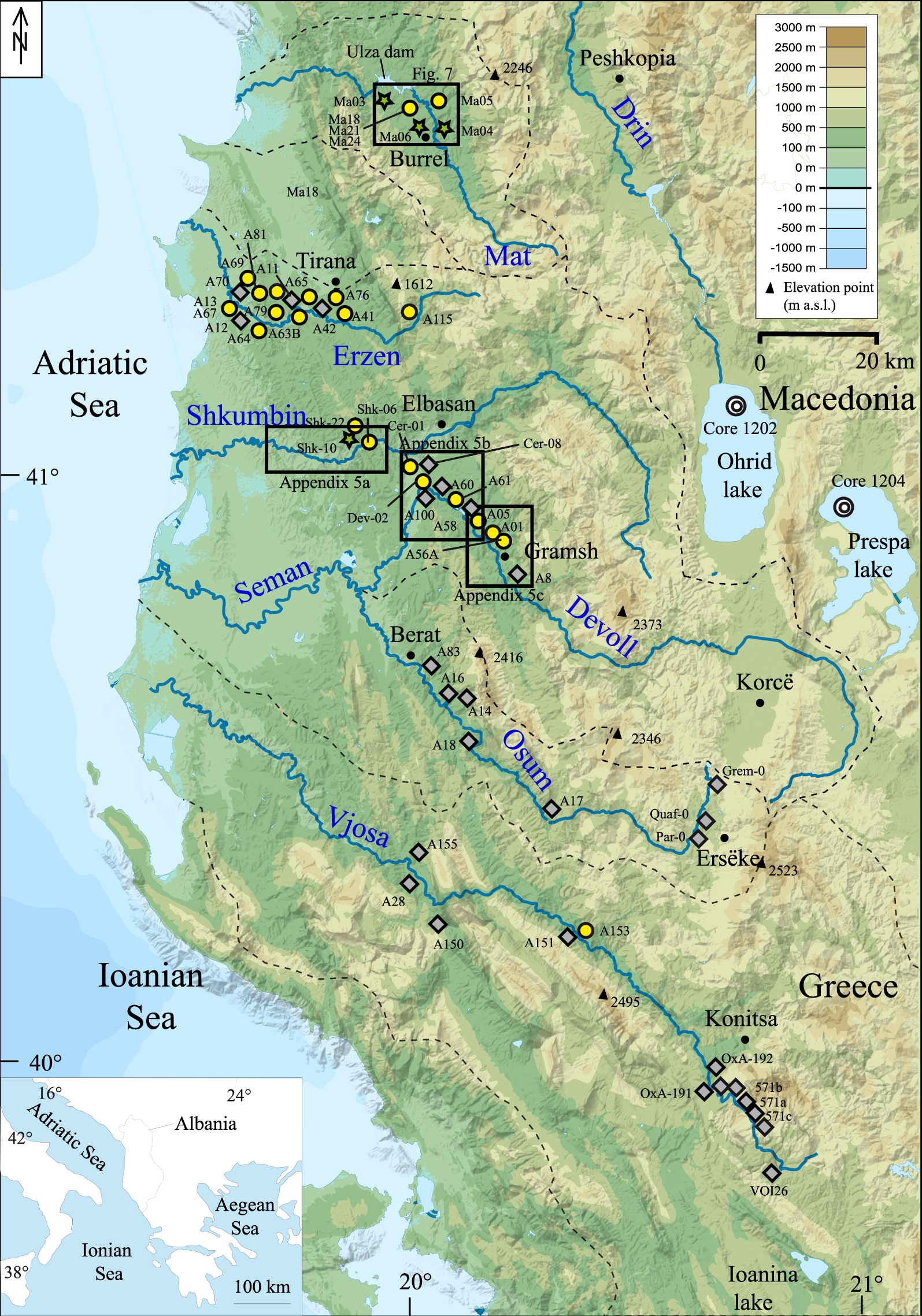

Terrace levels, formed during the last glacial cycle, are widely preserved along all the Albanian rivers [Woodward et al. 2008; Carcaillet et al. 2009; Koçiet al. 2018]. Albanian river catchments (Figure 1) are located in an area where large-scale controls (climate, tectonics or eustatism) can be considered similar: the climate is Mediterranean [Ozenda 1975], the tectonics is controlled by the Adriatic subduction beneath southeastern Europe [Roureet al. 2004] and all rivers have the same base level fluctuations linked to the eustatism [Lambeck and Chappell 2001].

Many studies have already described the general morphology of terraces [Melo 1961; Prifti 1981, 1984; Prifti and Meçaj 1987; Lewin et al. 1991; Woodward et al. 2008] and other studies have focused on the history of incision/uplift [Carcaillet et al. 2009; Guzmán et al. 2013; Gemignani et al. 2022]. But to make progress in understanding the genesis of terraces, numerical chronological constraints are necessary and are therefore proposed in this article.

There was few ages for the river terraces preserved in the central and northern part of Albania. Four 10Be and 21 14C new terrace ages, as well as geomorphological data, are reported in this paper. These data are combined with previous results in order to furnish an allostratigraphic/chronologic framework for the unit deposition and terrace formation during the past 200 ka along 7 Albanian rivers. This enriched database supported by 70 numerical ages is used to discuss the influence of climate changes on the genesis of terraces.

The rivers of Albania. (a) Topographic map of Albania derived from the 90-m Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) digital elevation model. Watersheds of the seven main Albanian rivers are bounded by black dashed lines. Dark diamonds indicate published data [Lewin et al. 1991; Hamlinet al. 2000; Woodward et al. 2001, 2008; Carcaillet et al. 2009; Guzmán et al. 2013; Koçiet al. 2018], yellow circles (14C dating) and green stars (10Be dating) indicate the data obtained in this study. The boxes show the location of Supplementary Information, Appendix 5 and Figure 7. Core 1202 and 1204 in the Ohrid and Prespa lakes refer to the work of Wagner et al. [2009, 2010, see Figure 9]. Masquer

The rivers of Albania. (a) Topographic map of Albania derived from the 90-m Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) digital elevation model. Watersheds of the seven main Albanian rivers are bounded by black dashed lines. Dark diamonds indicate published data [Lewin et al. ... Lire la suite

2. Methodology

Field surveys have been performed along all the rivers and the allostratigraphic units [Hughes 2010] were defined from an analysis of the lithostratigraphy and the geometry of the interface between Quaternary sediment and bedrock. Thicknesses and characteristics of the sedimentary units were observed in approximately one thousand sites. The terrace extension at large scale was mapped on the basis of field observations reported on topographic maps at the 1:25,000 scale [Institutin Topografik te Ushtrise Tirana 1990], 30-m digital elevation models [SRTM 2013] and satellite images (image@2023CNES/Airbus, available on Google Earth).

2.1. Dating of sedimentary units and terrace surfaces

In a first step, the relative chronology of the terraces was deduced for each river from the geometric relationship between the mapped terraces [Prifti 1981, 1984; Prifti and Meçaj 1987]. The correlation between the terrace remnants was performed by reconstructing a regular paleo-river profile from the upstream to downstream zones [Guzmán et al. 2013].

Although some relative methods, such as those based on the soil chronosequence, can differentiate the age of Middle Pleistocene sequences [Rowey and Siemens 2021], they were not used in this work: in the studied area, a dozen levels of terraces are distributed over a time period spanning one hundred thousand years [Carcaillet et al. 2009], a temporal distribution not favorable to the use of surface alteration as a time indicator [Rixhon 2022]. Furthermore, it has been shown that numeric dating is the best way to compare terrace chronologies at a large scale [Woodward et al. 2008] and that absolute dating techniques are necessary to correlate terraces with climatic stages [Schaller et al. 2016].

In a second step, the numeric ages of the terraces were determined. New data were based on radiocarbon (14C) and in situ produced 10Be dating. (See Supplementary Information, Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 for technical details.)

The 14C ages represent the death of organic material. Samples consist of plant remains or charcoal, a few millimeters in size (Supplementary Information, Figure S1b in Appendix 1), which are transported rapidly by rivers. Although there may be a delay between plant death and final deposition, we consider 14C ages to represent the age of sediment deposition. In order to exclude an eolian origin, that has sometimes been suggested in the Mediterranean area for the formation of the upper sub-unit of fine-grained deposits [Woodward et al. 2008; Obrehtet al. 2014; Cremaschiet al. 2015], the samples were taken from deposits also containing some coarse sands and small gravels or from fine-grained lenses within the coarse material (Supplementary Information, Figure S1c, Appendix 1). Therefore most 14C samples were collected close to the bottom of the upper sub-unit (see Supplementary Information, Figure S1a, Appendix 1).

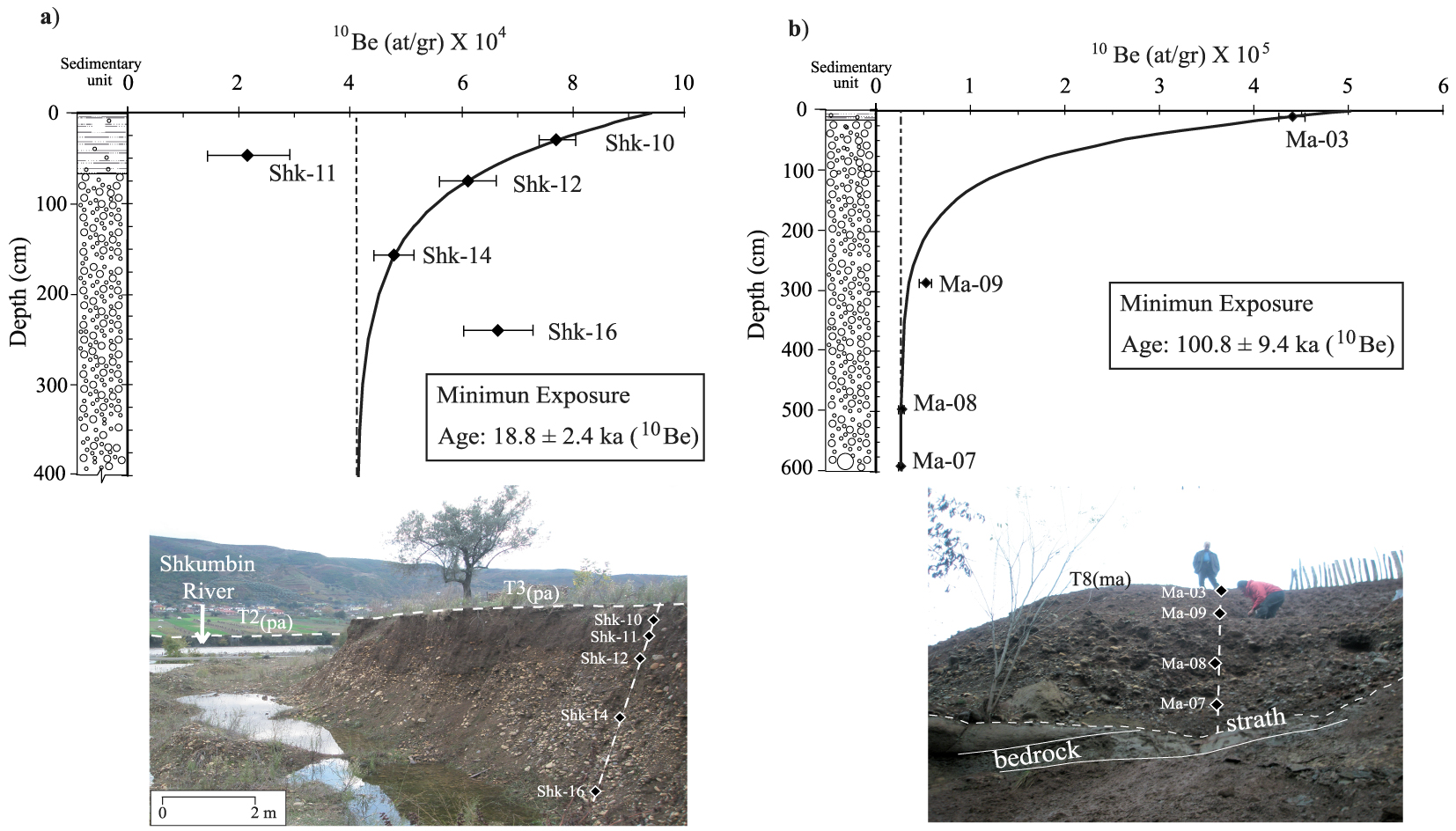

The 10Be ages represent the exposure ages of the terrace surfaces [Gosse and Phillips 2001]. The 10Be concentration on the terrace surface was measured in samples formed of amalgamated quartz clasts less than 5 cm in length. The attenuation of 10Be at depth was analysed by sampling cobble samples along one profile and amalgamated pebbles samples along another one [Gosse and Phillips 2001]; the best fit profiles and their uncertainties were then calculated using a Monte Carlo approach [Hidy et al. 2010] (Table 1). In addition to the new 10Be ages, the previously published 10Be ages were re-calibrated following the same procedure (Table 2).

Results of the 10Be analysis (see Figure 6 and the Supplementary Information, Appendix 2)

| Sample | Type of sample | Lithology | Latitude (° N) | Longitude (° E) | Altitude (m) | Depth (cm) | Shielding factor | 10Be concentration (105 at/g) | 10Be age (ka) | Terrace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower paleo-Devoll | ||||||||||

| Shk-10 | Cobble | Quarzite | 41.0618 | 19.8685 | 65 | 30 | 0.998 | 0.77 ± 0.07 | 18.81 ± 2.4 | T3(pa) |

| Shk-11 | Cobble | Granite | 47 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | ||||||

| Shk-12 | Amalgam.pebbles | Heterogeneous | 75 | 0.61 ± 0.03 | ||||||

| Shk-14 | Cobble | Granite | 157 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | ||||||

| Shk-16 | Cobble | Granite | 240 | 0.66 ± 0.05 | ||||||

| Mat river-Uzal Dam | ||||||||||

| Ma-03 | Amalgam.pebbles | Heterogeneous | 41.6748 | 19.9166 | 183 | 10 | 0.998 | 4.40 ± 0.14 | 100.8 ± 9.4 | T8(ma) |

| Ma-09 | Amalgam.pebbles | Heterogeneous | 285 | 0.52 ± 0.06 | ||||||

| Ma-08 | Amalgam.pebbles | Heterogeneous | 495 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | ||||||

| Ma-07 | Amalgam.pebbles | Heterogeneous | 590 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | ||||||

| Mat river-Livadhi | ||||||||||

| Ma-04 | Amalgam.pebbles | Heterogeneous | 41.5920 | 20.0336 | 262 | 0 | 1 | 5.63 ± 0.16 | ⩾112.32 ± 10.3 | T8(ma) |

| Mat river-Burrel | ||||||||||

| Ma-06 | Amalgam.pebbles | Heterogeneous | 41.6042 | 20.0130 | 322 | 0 | 1 | 10.04 ± 0.40 | ⩾193.92 ± 19.3 | T9(ma) |

Numeric ages from fluvial terraces of Albania

| Samplea | b | Latitude (° N)c | Long. (° E)c | Sample elevation above the river (m) | Sample depth below the surface (m) | Methodd | Lab-code reactor reference | 14C ages (ka) | Calibrated interval 14C Cal ka BP (Probability = 0.95) | Ages (ka)e | Local terrace name | Regional terrace name | Sourcef |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vjosa | |||||||||||||

| A153 | C | 40.2076 | 20.3875 | 17.3 | 0.7 | 14C | SacA 16001 | 190 ± 30 | 32–302 | - | - | colluv. | This study |

| A150 | C | 40.2084 | 20.0934 | 9.5 | 0.5 | 14C | SacA 15998 | 330 ± 30 | 308–473 | - | - | colluv. | (1) |

| A28 | Vd | 40.3354 | 19.9921 | 12 | 2 | 14C | Poz-8824 | 705 ± 30 | 565–691 | - | - | colluv. | (1) |

| OxA-192 | C | 39.97(ç) | 20.66(ç) | ∼4.5 | <1 | 14C | OxA-192 | 800 ± 100 | 560–928 | - | T1(vj) | T0 | (3) |

| OxA-191 | C | 40.87(ç) | 21.65(ç) | ∼4.5 | <1 | 14C | OxA-191 | 1000 ± 50 | 789–1049 | - | T1(vj) | T0 | (3) |

| A155 | Vd | 40.3611 | 19.9907 | 13.4 | 4 | 14C | SacA 16002 | 3870 ± 60 | 4094–4436 | - | - | colluv. | (1) |

| OxA-5246 | C | 39.96(ç) | 20.65(ç) | ∼10.6 | ∼0.1 | 14C | OxA-5246 | 13810 ± 130 | 16,291–17,116 | - | T3(vj) | T3 | (4) |

| Beta-109162 | C | 39.96(ç) | 20.65(ç) | ∼10.6 | ∼0.1 | 14C | Beta-109162 | 13960 ± 260 | 16,203–17,647 | - | T3(vj) | T3 | (4) |

| Beta-109187 | C | 39.96(ç) | 20.65(ç) | ∼10.4 | ∼0.4 | 14C | Beta-109187 | 14310 ± 200 | 16,865–17,947 | - | T3(vj) | T3 | (4) |

| VOI24 | S | 39.94(ç) | 20.71(ç) | ∼9.7 | <1 | TL | VOI24 | - | - | 19.60 ± 3.00 | T3(vj) | T3 | (3) |

| Tributary site | Cc | 39.95(ç) | 20.68(ç) | ∼10.5 | ∼1.6 | U/Th | - | - | - | 21.25 ± 2.50 | T3(vj) | T3 | (5) |

| Old Klithonia | Cc | 39.96(ç) | 20.65(ç) | ∼9.3 | ∼2.3 | U/Th | - | - | - | 24.00 ± 2.00 | T4(vj) | T4 | (5) |

| 571c | Dt | 39.96(ç) | 20.68(ç) | ∼12.4 | ∼7.5 | ESR | 571c | - | - | 24.30 ± 2.60 | T4(vj) | T4 | (3) |

| 571a | Dt | 39.96(ç) | 20.68(ç) | ∼12.4 | ∼7.5 | ESR | 571a | - | - | 25.00 ± 0.50 | T4(vj) | T4 | (3) |

| Old Klithonia | Cc | 39.96(ç) | 20.65(ç) | ∼9.3 | ∼5 | U/Th | - | - | - | 25.00 ± 2.00 | T4(vj) | T4 | (5) |

| 571b | Dt | 39.96(ç) | 20.68(ç) | ∼12.4 | ∼7.5 | ESR | 571b | - | - | 26.00 ± 1.90 | T4(vj) | T4 | (3) |

| VOI23 | S | 39.96(ç) | 20.68(ç) | ∼12.4 | <1 | TL | VOI23 | - | - | 28.00 ± 7.10 (£) | T4(vj) | T4 | (3) |

| A151 | C | 40.2140 | 20.3842 | 21.7 | 0.3 | 14C | SacA 15999 | 24070 ± 150 | 27,783–28,848 | - | T5(vj) | T5 | This study |

| Konitsa1 | Cc | 39.86(ç) | 20.77(ç) | ∼10 | ∼1–1.5 | U/Th | - | - | - | 53.00 ± 4.00 | T6(vj) | T8 | (5) |

| Konitsa2 | Cc | 39.86(ç) | 20.77(ç) | ∼10 | ∼1-1.5 | U/Th | - | - | - | 56.50 ± 5.00 | T6(vj) | T8 | (5) |

| Konitsa3 | Cc | 39.86(ç) | 20.77(ç) | ∼11 | ∼1–1.5 | U/Th | - | - | - | 74.00 ± 6.00 | T7(vj) | T9 | (5) |

| Konitsa4 | Cc | 39.86(ç) | 20.77(ç) | ∼12.7 | ∼1–1.5 | U/Th | - | - | - | 80.00 ± 7.00 | T7(vj) | T9 | (5) |

| Konitsa5 | Cc | 39.86(ç) | 20.77(ç) | ∼15.5 | ∼1–1.5 | U/Th | - | - | - | 113.00 ± 6.00 | T8(vj) | T10 | (5) |

| VOI26 | S | 39.86(ç) | 20.77(ç) | ∼56 | ∼22 | TL | VOI26 | - | - | >150(£) | T9(vj) | T12 | (3) |

| Osum | |||||||||||||

| A17 | Vd | 40.4508 | 20.2808 | 17 | 2 | 14C | Poz-10576 | 9990 ± 50 | 11,263–11,705 | - | T2(os) | T2 | (2) |

| Par-0 (*) | Sr | 40.5200 | 20.7200 | 70 | 0 | 10Be | - | - | - | 19.25 ± 1.3 | T3(os) | T3 | (2) |

| Quaf-0 (*) | Sr | 40.5500 | 20.6900 | 29 | 0 | 10Be | - | - | - | 20.33 ± 1.5 | T3(os) | T3 | (2) |

| A16 | Vd | 40.6394 | 20.0553 | 24 | 4 | 14C | Poz-10575 | 29900 ± 1300 | 31,323–37,457 | - | T5(os) | T6 | (2) |

| A83 | C | 40.6800 | 20.0200 | 14.8 | 3.7 | 14C | Poz-13850 | 37000 ± 300 | 41,036–42,066 | - | T6(os) | T7 | (2) |

| A18 | Vd | 40.5600 | 20.1400 | 53 | 6 | 14C | Poz-10578 | 45300 ± 1600 | >46237 | 50.70 ± 1.80 ($) | T7(os) | T8 | (2) |

| A14 | Vd | 40.6403 | 20.0575 | 33.8 | 1.2 | 14C | Poz-10574 | 49000 ± 2500 | >49928 | 54.40 ± 2.78 ($) | T7(os) | T8 | (2) |

| Grem-0(*) | Sr | 40.5560 | 20.7383 | 50 | 0 | 10Be | - | - | - | 54.01 ± 3.0 | T7(os) | T8 | (2) |

| Paleo-Devoll | |||||||||||||

| A05 | Vd | 40.9092 | 20.1393 | 34 | 2 | 14C | Poz-10572 | 119.5 ± 0.3 pMC | - | modern | - | colluv. | This study |

| Cer-08 | C | 41.0275 | 19.9817 | 8.4 | 0.6 | 14C | Poz-39495 | 30 ± 80 | 9–275 | - | - | colluv. | (1) |

| Dev-02 | C | 40.9910 | 20.0165 | 16.6 | 0.5 | 14C | Poz-39496 | 540 ± 130 | 306–727 | - | - | colluv. | (1) |

| Shk-06 | Vd | 41.0663 | 19.8800 | 52.8 | 2.2 | 14C | Poz-34987 | 162 ± 0.46 pMC | modern | - | colluv. | This study | |

| Shk-22 | C | 41.0649 | 19.8714 | 6.3 | 0.7 | 14C | Poz-39201 | 90 ± 30 | 22–266 | - | - | colluv. | This study |

| Cer-01 | C | 41.0100 | 20.0083 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 14C | Poz-39197 | 5400 ± 40 | 6021–6293 | - | T2(pa) | T1 | This study |

| Shk-10(*) | Sr | 41.0618 | 19.8685 | 14.7 | 0.3 | 10Be | - | - | 18.81 ± 2.4 | T3(pa) | T3 | This study | |

| A60 | C | 40.9676 | 20.0526 | 19 | 0.5 | 14C | Poz-12223 | 17640 ± 160 | 20,895–21,800 | - | T3(pa) | T3 | (1) |

| A58 | C | 40.9214 | 20.1292 | 15.7 | 3 | 14C | Poz-12116 | 21850 ± 150 | 25,815–26,437 | - | T4(pa) | T4 | (1) |

| A100 | C | 40.9660 | 20.0636 | 24 | 1 | 14C | Poz-17242 | 22780 ± 200 | 26,583–27,490 | - | T4(pa) | T4 | (1) |

| A8 | Vd | 40.8271 | 20.2154 | 42.5 | 5 | 14C | Poz-9838 | 23760 ± 150 | 27,580–28,163 | - | T5(pa) | T5 | (1) |

| A1 | Vd | 40.8836 | 20.1773 | 42 | 6 | 14C | Poz-8816 | 25500 ± 300 | 28,921–30,498 | - | T5(pa) | T5 | This study |

| A61 | C | 40.9414 | 20.1089 | 41.2 | 1 | 14C | Poz-12117 | 38900 ± 700 | 41,939–44,142 | - | T7(pa) | T7 | This study |

| A56A | C | 40.8834 | 20.1764 | 41 | 3 | 14C | >52000 | >52 | T8(pa) | T8 | This study | ||

| Erzen | |||||||||||||

| A41 | C | 41.2697 | 19.8400 | 3 | 1.5 | 14C | Poz-8826 | 170 ± 30 | 35–291 | - | - | colluv. | (6) |

| A11 | C | 41.2900 | 19.7100 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 14C | Poz-8818 | 200 ± 30 | 25–304 | - | - | colluv. | (6) |

| A81 | C | 41.2866 | 19.7094 | 23.4 | 1 | 14C | Poz-13849 | 275 ± 35 | 152–459 | - | - | colluv. | This study |

| A65 | C | 41.3088 | 19.7544 | 29 | 0.8 | 14C | Poz-12784 | 500 ± 30 | 501–617 | - | - | colluv. | This study |

| A76 | Vd | 41.2800 | 19.8300 | 11.7 | 1 | 14C | Poz-13847 | 3075 ± 35 | 3182–3372 | - | - | colluv. | This study |

| A63B | C | 41.2870 | 19.7197 | 17 | 3 | 14C | Poz-12118 | 3700 ± 35 | 3927–4150 | - | - | colluv. | This study |

| A13 | C | 41.2700 | 19.6400 | 9 | 0.4 | 14C | Poz-8823 | 1660 ± 30 | 1421–1690 | - | T1(er) | T0 | (6) |

| A12 | C | 41.2700 | 19.6400 | 9 | 1 | 14C | Poz-10573 | 1730 ± 30 | 1564–1708 | - | T1(er) | T0 | This study |

| A42 | Vd | 41.2700 | 19.8000 | 12 | 1 | 14C | Poz-8827 | 6840 ± 60 | 7578–7817 | - | T2(er) | T1 | (6) |

| A115 | C | 41.2844 | 19.9683 | 17 | 0.8 | 14C | Poz-17243 | 26600 ± 500 | 29,631–31,465 | - | T3(er) | T5 | This study |

| A67 | C | 41.2700 | 19.6400 | 9.4 | 3 | 14C | Poz-12120 | 30400 ± 300 | 33,889–34,912 | - | T4(er) | T6 | This study |

| A69 | C | 41.2900 | 19.6400 | 41 | 1.2 | 14C | Poz-12121 | 31500 ± 400 | 34,671–36,231 | - | T4(er) | T6 | (6) |

| A64 | C | 41.2700 | 19.7100 | 24.8 | 0.8 | 14C | Poz-12224 | 33400 ± 500 | 36,358–38,827 | - | T4(er) | T6 | This study |

| A79 | C | 41.2900 | 19.7100 | 26.5 | 2 | 14C | Poz-13848 | 44200 ± 1600 | >45447 | 49.59 ± 1.76($) | T6(er) | T8 | This study |

| A70 | C | 41.2900 | 19.6000 | 22 | 0.5 | 14C | Poz-12785 | 48000 ± 2000 | >49910 | 53.40 ± 2.22($) | T6(er) | T8 | (6) |

| Mat | |||||||||||||

| Ma-05 | C | 41.6178 | 20.0294 | 24.3 | 0.7 | 14C | Poz-34984 | 1075 ± 30 | 931–1056 | - | - | colluv. | This study |

| Ma-18 | C | 41.6245 | 19.9978 | 7 | 0.7 | 14C | Poz-39198 | 1725 ± 30 | 1562–1706 | - | T1(ma) | T0 | This study |

| Ma-21 | C | 41.6246 | 19.9970 | 10.3 | 0.7 | 14C | Poz-39199 | 5100 ± 40 | 5746–5922 | - | T2(ma) | T1 | This study |

| Ma-24 | C | 41.6273 | 19.9968 | 26 | 2.1 | 14C | Poz-39200 | 14850 ± 80 | 17,856–18,296 | - | T3(ma) | T3 | This study |

| Ma-04(*) | Sr | 41.5920 | 20.0336 | 100 | 0 | 10Be | - | - | - | 100.8 ± 9.4 | T8(ma) | T10 | This study |

| Ma-03 | Sr | 41.6748 | 19.9166 | 94 | 0.1 | 10Be | - | - | - | ⩾112.32 ± 10.3 | T8(ma) | T10 | This study |

| Ma-06 | Sr | 41.6042 | 20.0130 | 190 | 0 | 10Be | - | - | - | ⩾193.92 ± 19.3 | T9(ma) | T11 | This study |

| Drin | |||||||||||||

| TPN(*) | Ca | 42.37855 | 20.08971 | 12 | 0.5 | 36Cl | - | - | - | 8.2 ( − 2∕ + 4) | T2(dr) | T1 | (7) |

| TPS(*) | Ca | 42.34380 | 20.11545 | 56 | 0.4 | 36Cl | - | - | - | 12.3 ( − 2∕ + 5) | T3(dr) | T2 | (7) |

aSamples: (∗) for a cosmogenic depth profile, only the age of the surface and the depth of the shallowest sample are given. bType of material dated: C = charcoal, Vd = vegetal debris, Cc = calcite cement, S = sediment, Dt = deer tooth, Sr = siliceous rock, Ca = Calcereous rock. cLocation from GPS coordinates or (ç) estimated from published maps. dDating method: 14C = radiocarbon, TL = thermoluminescence, U/Th = uranium series, ESR = electron spin resonance, 10Be and 36Cl = cosmogenic in situ produced data. eNumerical ages: all 10Be ages have been calculated (Table 1) or recalculated with the parameters indicated in Supplementary Information, Appendix 2. All 14C ages have been estimated from the IntCal 13 calibrated intervals and the oldest ($) were also corrected using the polynomial calibration of Bard et al. [2004]. (£) Have not been considered for the probability density curves due to their large uncertainty. fSource: (1) Guzmán et al. [2013], (2) Carcaillet et al. [2009], (3) Lewin et al. [1991], (4) Woodward et al. [2008], (5) Hamlinet al. [2000], (6) Koçiet al. [2018], (7) Gemignani et al. [2022].

The limestone pebble-rich terraces of the Drin River [Gemignani et al. 2022] have been dated using 36Cl. Other ages [Lewin et al. 1991; Woodward et al. 2008] refer to the mineral formation (U/Th) or the time without daylight exposure (ESR and TL) within the alluvium and are older than the ultimate phases of river aggradation [Noller et al. 2000].

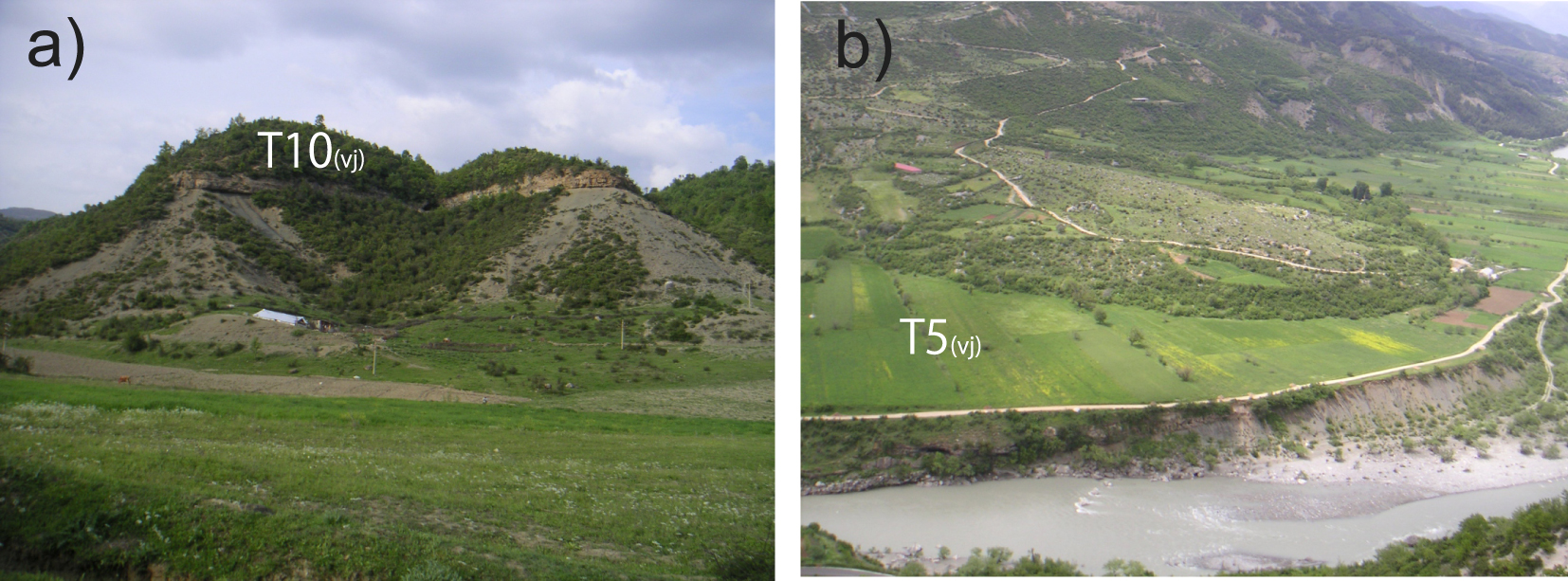

Examples of sedimentary units and terraces in Albania. (a) Remnant of a fill terrace (T10(vj)), middle section of the Vjosa River; (b) Debris flow deposited above T5(vj) terrace.

3. Setting

3.1. Climate and paleoclimate of Albania

Albania’s present climate is Mediterranean on the coast, with 2 to 3 hot, dry months in summer and 4 to 5 mild, rainy months in winter. In the mountainous regions, the climate is continental with cold and snow-covered winters.

The paleo climatic records for the last 500 ka were studied in the region in Lake Ohrid, [Sadori et al. 2016] and Lake Ioannina [Roucoux et al. 2008] (location on Figure 1). These local records correspond well with the results found in the isotope record of Greenland [Grootes et al. 1993] or in the marine records of the Iberian margin [de Abreu et al. 2003] and the eastern Mediterranean [Konijnendijk et al. 2015]. They show a succession of cold periods followed by rapid warm excursions [Clement and Peterson 2008].

The Adriatic Sea, which controls the base level of Albania’s rivers, was affected by eustatic fluctuations which are tuned to the global sea level variations and ranged from −120 m to +10 m during the last glacial period [Lambeck and Chappell 2001]. Colder sea surface temperatures that occurred in the Mediterranean Sea [Cacho et al. 1999; Sánchez Goñi et al. 2002; Geraga et al. 2005] during Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 5 to 2 were linked to the polar water that entered through the Strait of Gibraltar and were closely related to ice rafting events in the northeast Atlantic, called Heinrich events (HEs) [Heinrich 1988]. These short cold events [one to two thousand years; Chappell 2002; Ziemen et al. 2019] or even less [Bond et al. 1992; Hemming 2004] were always followed by warm periods [Rahmstorf 2002]. Therefore, the temperature evolution of the Albanian region at the millennial scale is similar to that of the north Atlantic domain [e.g. Sánchez Goñi et al. 2002; Tzedakis et al. 2004].

The climatic-water-balance of the landscape (ratio between rainfall, runoff, evapotranspiration, etc.) induces complex connection between temperature and precipitation within the region and a decline in precipitation probably occurred in the western Mediterranean Sea during the Heinrich events. They induced cooler sea surface temperatures that inhibited the moisture supply to the atmosphere [Kallel et al. 1997, 2000] whereas increased rainfalls in the western Mediterranean region are evidenced during warm intervals by the sapropel records [Toucanne et al. 2015].

Thus, it is expected that high-frequency Heinrich events induced rapid climatic changes in the Mediterranean region with a succession of dry and cold events followed by rapid warming and moisture return [Toucanne et al. 2015]. Lacustrine sediments in eastern Albania also recorded HEs-induced climatic changes through proxies of the alteration, like a high concentration of manganese and total inorganic carbon [Wagner et al. 2010] and a high zirconium/titanium ratio [Wagner et al. 2009].

3.2. Geology and rivers of Albania

The Albanian mountains are parts of the fold belt, which was thrusted westward during the subduction of the Adriatic plate beneath southeastern Europe [Roureet al. 2004]. The eastern side of Albanides mainly consists of Jurassic ophiolites and Mesozoic carbonates. The western side of Albanides is mainly formed of carbonates topped by Mesozoic or Cenozoic flysch deposits [Robertson and Shallo 2000]. A foreland basin, filled with Plio-Quaternary molasse deposits, forms the coastal plain [Roureet al. 2004].

The late Pleistocene uplift rate, inferred from fluvial incision, locally reaches 2.8 mm/yr in the Albanian mountain but is generally in the range 0.5 to 1.0 mm/yr [Carcaillet et al. 2009; Guzmán et al. 2013; Biermanns et al. 2018]. Permanent GPS stations indicate the same range of values for the present-day vertical motion in Albania (Jouanne, personal communication).

The main Albanian rivers are, from south to north, the Vjosa, Osum, Devoll, Shkumbin, Erzen, Mat and Drin rivers (Figure 1) and all of them are less than 272 km long.

Fluvial terrace deposition punctuates the vertical incision along all the main Albanian rivers (Figure 2) and most of them are located above soft clastic (flysch or molasses) sediments. The terraces of the upper Vjosa River (also called Voidomatis in Greece), the middle Vjosa River, the Osum River, the Erzen River and the Drin River were previously mapped and dated by Woodward et al. [2008], Hauer et al. [2021], Carcaillet et al. [2009], Koçi [2007] and by Gemignani et al. [2022], respectively. We performed an analysis of the terrace geometry and new dating for the Devoll, Skumbin, Mat and Erzen rivers, previously poorly studied. The lower part of the Drin River has not been studied because it is drowned by several artificial dams.

4. Terrace geomorphology and ages along the seven Albanian rivers

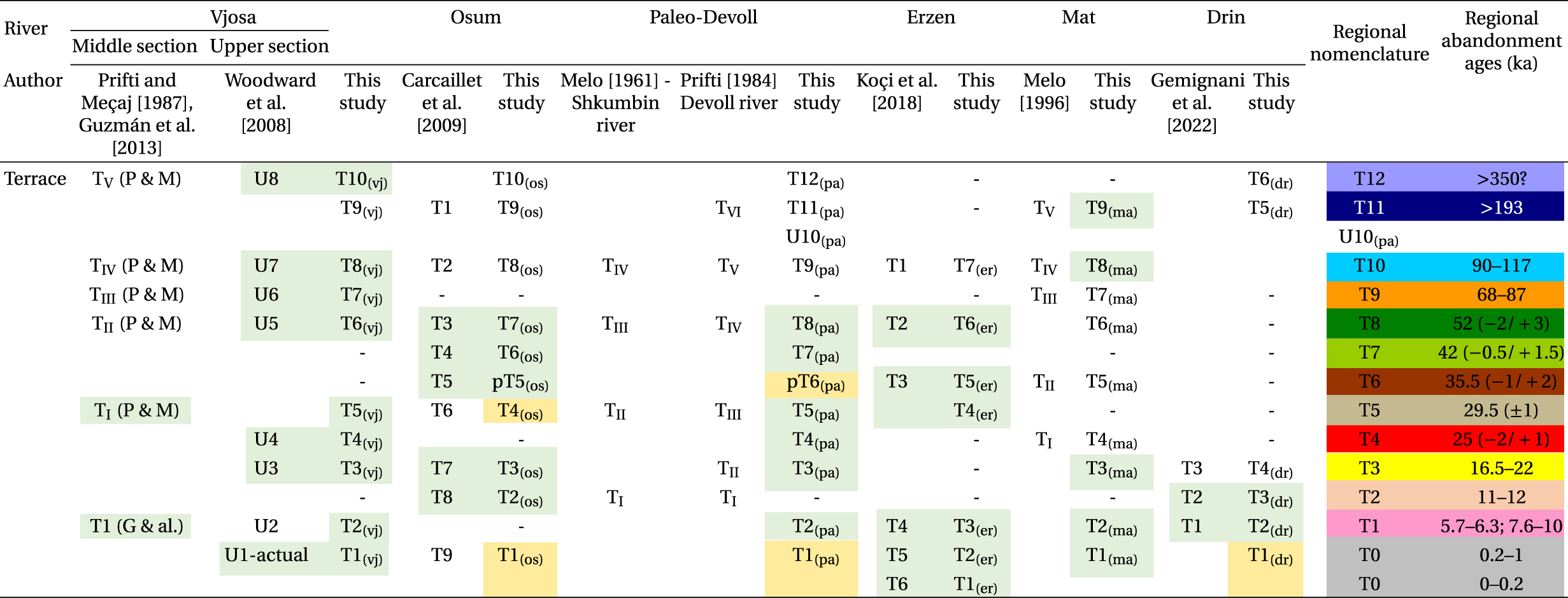

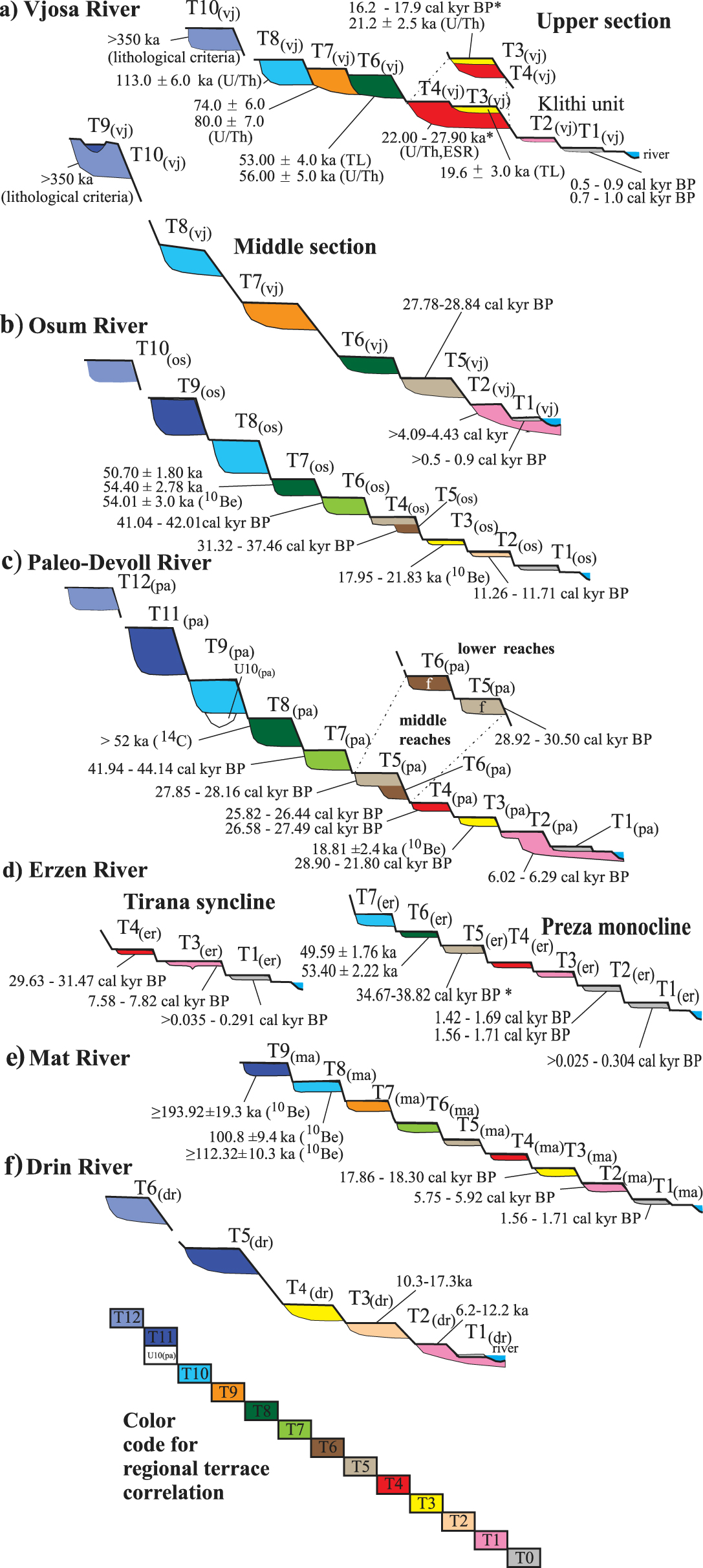

A synthesis of the numerical dating and terrace geometry is presented for the rivers of Albania and northwestern Greece. A nomenclature is proposed, where the successions of terraces surface for each river are called Tx(river) and terrace indices increase with age. Units are nonetheless labelled Ux(river) when the terrace surface, fully eroded, cannot be defined. A correlation of this nomenclature with those used by the previous terrace studies is shown in Table 3 and detailed in Supplementary Information, Appendix 3.

Correlation of the local terrace nomenclatures with a regional nomenclature for the terraces identified along the Albanian rivers

|

The light green cells refer to dated levels; light yellow and white cells refer to not dated levels, well correlated or poorly correlated, respectively. The colored cells on the right side refer to the color code of Figures 3, 5, 7 and 9. The regional ages of the terrace and their uncertainties (68% probability interval) are obtained from the probability density curves of the numerical dating for terraces younger than 60 ka (see text and Figure 9). “P & M” stands for Prifti and Meçaj [1987] and “G and al.” stands for Guzmán et al. [2013].

4.1. Previous studies of the Vjosa, Drin and Osum river terraces

The Vjosa River is more than 272 km long and is made up of sections with very different morphologies [Hauer et al. 2021].

In the upper section (Konista area, Figure 1), eight units (Figure 4a), including the present-day channel (T1(vj)), were identified. They were dated, except T2(vj), using different methods (14C, U/Th, ESR, TL) [Lewin et al. 1991; Hamlinet al. 2000; Woodward et al. 2001, 2008] (Table 2). The highest terrace was deposited by a river system with a much larger catchment that was pirated before 350 ka [Macklin et al. 1997].

In the middle section of the Vjosa River, the long-term incision rate is greater than in the upper section [Guzmán et al. 2013]. The elevation of the highest terrace T10(vj) (Figure 3a) is more than 160 m [Prifti 1981] and our field work has shown that the conglomerate unit of T10(vj) is preserved between paleo-meanders filled by sediment of T9(vj). Prifti and Meçaj [1987] mapped five terrace levels and Guzmán et al. [2013] mapped another terrace level T2(vj) that is located at the top of a thick sedimentary unit that extends several tens of meters below the present river [Prifti 1981].

The units beneath the terrace surfaces are mainly formed of rounded fluvial clasts. Nonetheless, angular calcareous clasts are locally intercalated within the fluvial units and are related to debris flows (Figure 3b) provided by very steep calcareous slopes. Guzmán et al. [2013] dated colluvium above the top of T2(vj).

We dated in this paper T5(vj) with an age intercalated between those found in the upper section for T4(vj) and T6(vj) [Woodward et al. 2008]. Hence, when the upper and middle sections of the Vjosa River are considered, ten river terrace levels are identified and only T9(vj) is not dated (Figure 3a, Table 2).

Along the Drin River, four terraces are described [Aliajet al. 1996; Pashko and Aliaj 2020]. Our personal work close to Peshkopia area (Figure 1) has revealed two others higher terraces, T5(dr) and T6(dr) (Figure 3f). Only T2(dr) and T3(dr) terraces were dated [Gemignani et al. 2022] (Table 2).

In the Osum River area, nine terraces were mapped [Carcaillet et al. 2009] and our complementary observations indicate remnants of a fill terrace (T10(os)) more than 150 m above the present-day river (Figure 3b). The sedimentary unit linked to T4(os) is superimposed above another allostatigraphic unit U5(os) in the middle reaches of the Osum River [Carcaillet et al. 2009]. Using 14C and 10Be dating methods, Carcaillet et al. [2009] dated T7(os), T6(os), T3(os), and T2(os) and also U5(os) (Table 2).

Ages and simplified geometry of the terraces identified along the 7 main Albanian rivers (a–f; see text). The horizontal and vertical axes are not to scale. The local terrace nomenclature TX(loc) is indicated for each river. The color of the terraces indicates the inferred correlation with the regional nomenclature T0 to T12 (Same colors as cells of Table 3). The ages refer to the numerical ages of Table 2. Ages are shown as a unique interval with an “*” if there are three or more numeric dates for one terrace level. Masquer

Ages and simplified geometry of the terraces identified along the 7 main Albanian rivers (a–f; see text). The horizontal and vertical axes are not to scale. The local terrace nomenclature TX(loc) is indicated for each river. The color of the ... Lire la suite

4.2. New results about the paleo-Devoll, Mat and Erzen terraces

4.2.1. A paleo-Devoll River defined from the Devoll and Shkumbin terraces

The Devoll River flows over 205 km. Downstream from the confluence with the Osum River, it forms the Seman River (Figure 5a).

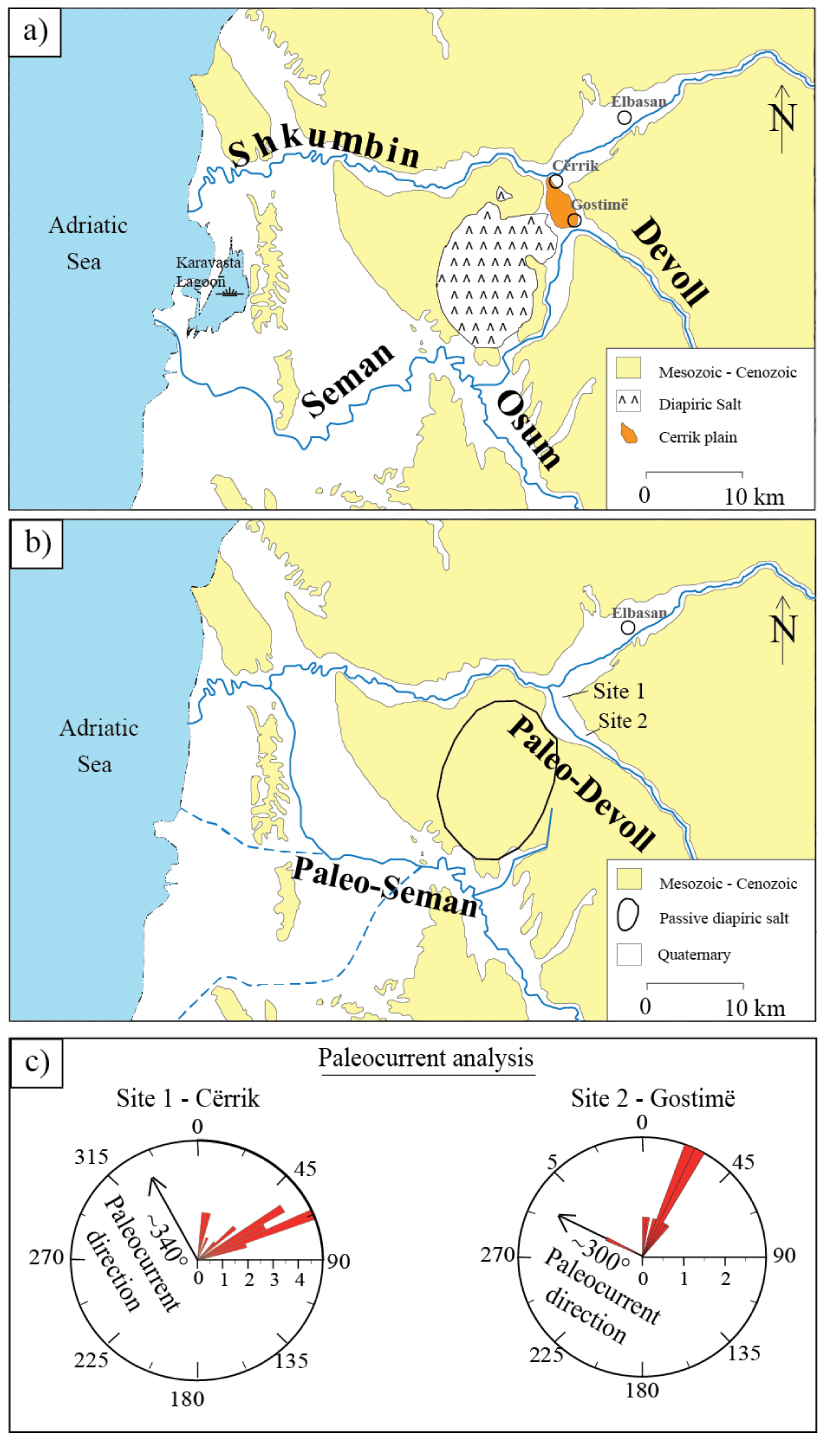

The Shkumbin River is 181 km long and the Devoll and Shkumbin are two nearby rivers that are presently separated by the Cërrik plain spanning approximately 20 km2. Today, no river flows through this plain (Figure 5a) that dips ∼0.1° toward the northwest but terraces of a paleo-river are perched above its eastern border. The Cërrik plain is located over a thick sedimentary unit [Prifti and Meçaj 1987] and the scarp cut by the Devoll River shows a >12 m-thick deposit formed of pebbles supported by a sandy to silty matrix. Our measurements of imbricate clasts and cross stratification indicate paleo-flow directions around N 300° and N 340° during deposition (site 1 and 2 on Figure 4c and Supplementary Information, Appendix 4). This suggests that the paleo-Devoll River flowed northward and connected to the Shkumbin River. Hence, the terraces located along the middle reaches of the Devoll and the lower reaches of the Shkumbin form a unique terrace system that extends more than 100 km.

Evolution of the connections between the Devoll, Osum, Seman and Shkumbin rivers. (a) Present-day configuration. (b) Previous configurations. The age of the capture of the Devoll by the Seman is estimated at 6 ka (see text). The paleo-Seman River from Chabreyrou [2006, full line] and Fouache et al. [2010, dashed lines]. (c) Rose diagrams of the paleo-flow directions inferred from imbricate clasts and cross stratification. Location of sites 1 and 2 on Figure 4b (data in the Supplementary Information, Appendix 4).

Four and six terrace levels were initially identified along the Shkumbin [Melo 1961] and Devoll [Prifti 1984] rivers, respectively. In this study (Supplementary Information, Appendix 5), we mapped and correlated eleven terrace levels along the paleo-Devoll River (Table 3 and Figure 3c). Their sedimentary units were generally deposited on straths beveled in the flysch or molasse substratum.

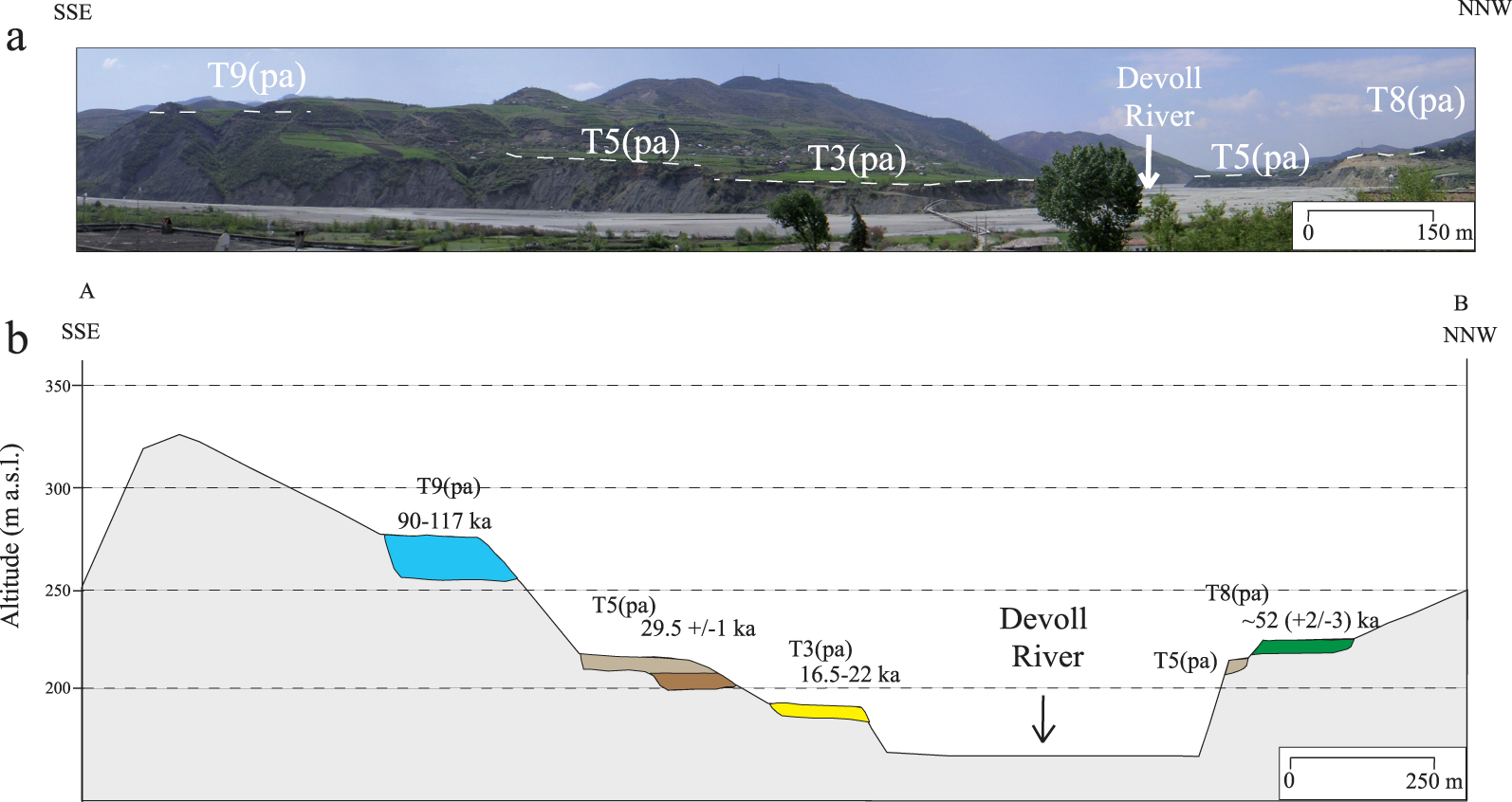

The terraces of the upper reaches of the Devoll River. (a) Panoramic view and (b) cross-section through the terraces. The ages refer to the regional nomenclature and to the most likely age of abandonment proposed in this study (Table 3).

The mean thickness of T12(pa), T11(pa), T9(pa), T8(pa), T7(pa), pT6(pa), and T5(pa), T4(pa) and T3(pa) vary between 6 and 32 m and two superposed sub-units, that are part of parts of the same fluvial process, are found beneath all these terraces: A thin upper sedimentary sub-unit (∼1 m) is composed of clay, siltstone and fine sand. Nevertheless, its thickness reaches more than 2 m beneath the oldest terraces (T12(pa), T11(pa) and T9(pa)) and possibly includes loess and colluvium deposited after the fluvial story. The basal sub-unit consists of rounded pebbles and cobbles that are supported by a gravel and sand matrix. The clast size generally fines upward, while the percentage of matrix increases. Nonetheless, the size of the coarse material shows complex variations and conglomerate sometimes alternate with horizontal stratified, fine to coarse sand levels. Sediments of the basal unit were deposited in a braided alluvial system characterized by cross-stratified rounded pebbles and cobble levels that alternate with horizontal stratified, fine to coarse sand levels.

The upper part of T10(pa) is fully eroded and U10(pa) is only found beneath an erosional surface in the continuity of the strath at the bottom of T9(pa). Evidence of a meandering environment is found within the unit U10(pa) (Figure 3c) where sediments dip steeply and were possibly deposited at the intrados of meanders.

In the lower reaches of the paleo-Devoll catchment, a cosmogenic depth profile (Figure 8a) yielded a minimum exposure age for T3(pa) (Table 1; see the description in Supplementary Information, Appendix 2) and seven 14C samples were collected along the paleo-Devoll River (Table 2). These results, combined with the eleven 14C dates [Guzmán et al. 2013] gave ages for T8(pa), T7(pa), T5(pa), T4(pa), T3(pa), and T2(pa). Furthermore, the 14C dating of colluvium deposited above T1(pa) provides an age for the abandonment of this terrace.

The 10Be concentration along the depth profiles. (a) T3(pa) in the lower reaches of the paleo-Devoll River (location of Sk-10 on the Supplementary Information, Figure S4a in Appendix 5); (b) T8(ma) in the middle reaches of the Mat River (Ulza Dam, location on Figure 7). Solid lines indicate the best-fit for the depth-production profile; the dashed line shows the inherited 10Be concentration. Details are given in Table 1 and in the Supplementary Information, Appendix 2.

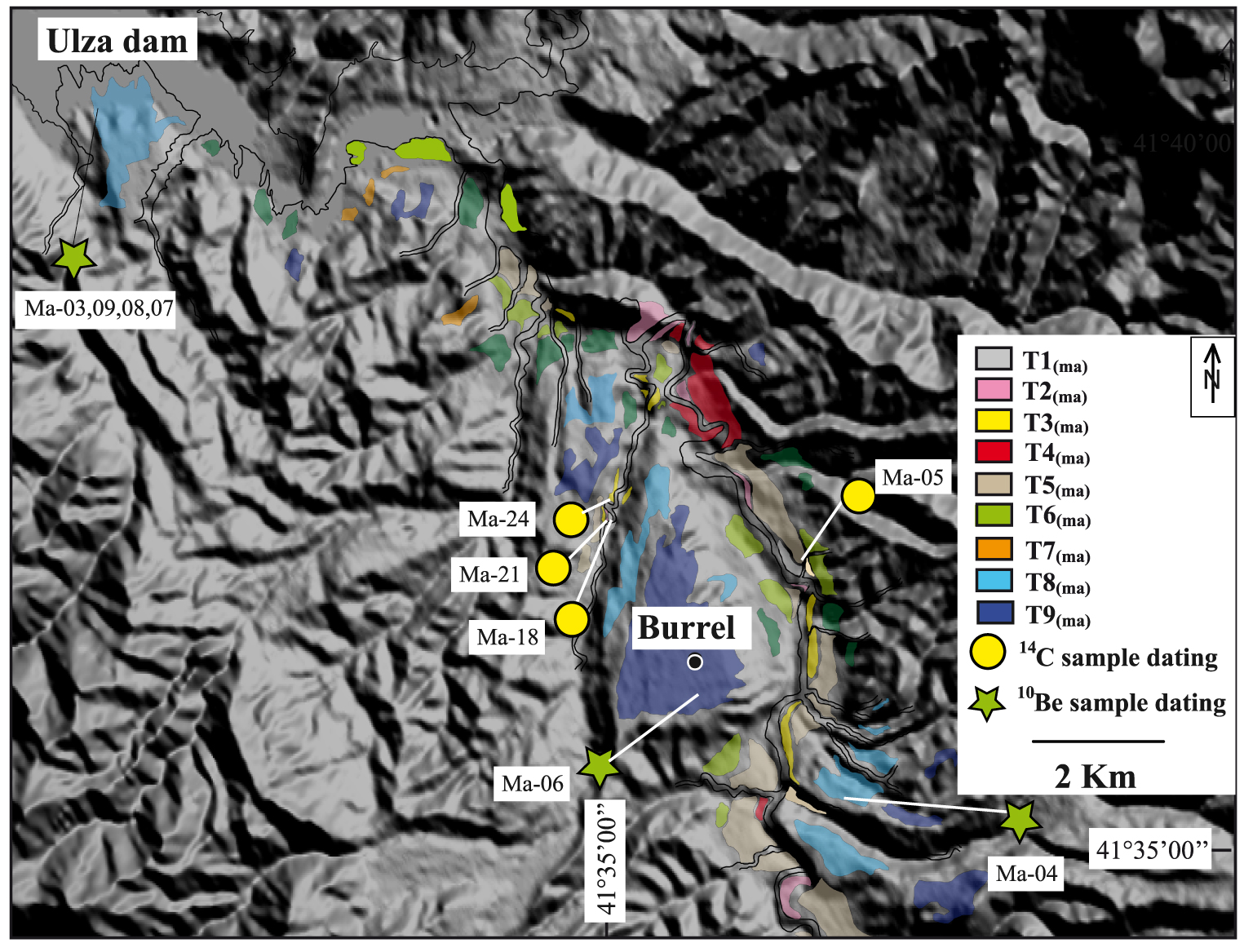

Geomorphologic map of the Mat River. Location on Figure 1. The numbers refer to the samples of Table 2.

4.2.2. Characteristics and numerical ages of the Mat terraces

Five terraces were previously described along the Mat River [Melo 1996]. Nine terraces (Figure 3e) were mapped during our fieldwork (Figure 7).

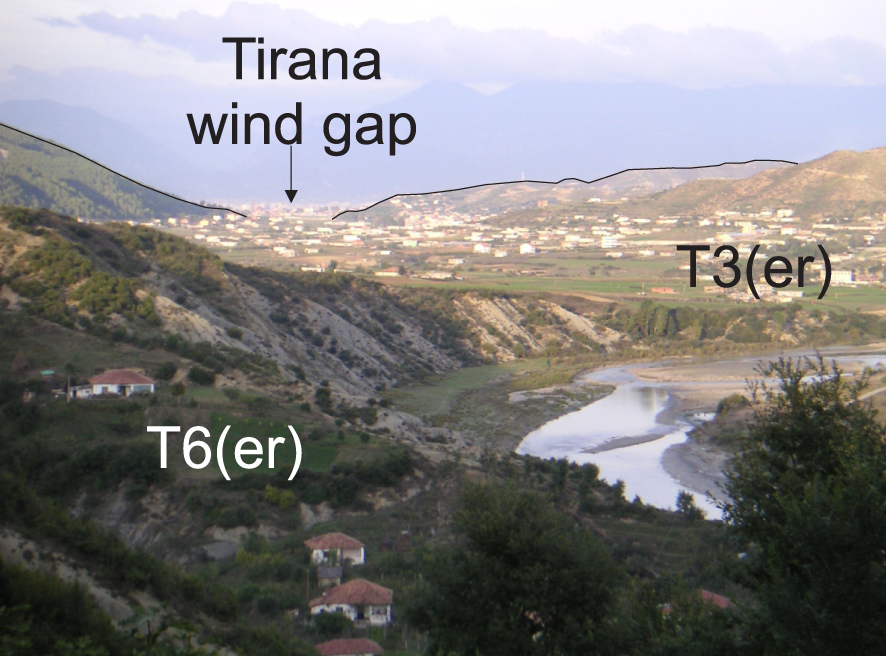

Terraces of the Erzen River. (T3(er)) extending toward the Tirana wind gap.

The two oldest terraces were dated using the 10Be method. Amalgams of siliceous pebbles (e.g. radiolarites, chert, quartz), were taken at the top of T9(ma) and T8(ma) (Ma-06 and Ma-04in Table 1; location on Figure 7). A cosmogenic depth profile was made through the sedimentary unit of terrace T8(ma) (Figure 6b). Terraces T3(ma), T2(ma), T1(ma) and the colluvium deposited above T1(ma) were dated from charcoal samples (Table 2 and Figure 3e).

4.2.3. Characteristics and numerical ages of the Erzen terraces

The terraces of the Erzen River have been mapped by Koçi [2007] and an active back-thrust fault separates two domains [Ganas et al. 2020]. In the western uplifted domain (Prespa monocline), seven levels of terraces were recognized (Figure 3d) whereas in the eastern domain (Tirana syncline), only three terrace levels were recognized. A correlation between the terraces on each side of the back-thrust fault is made using the 15 14C dates (Table 2) and seven terrace levels were identified along the Erzen River (T7(er) to T1(er)), and only the oldest level is not numerically dated. The terrace T3(er) is highly extended, in peculiar across a wind gap (Figure 8), which corresponds to a paleo river that flowed close to Tirana (Figure 1).

5. Discussion

5.1. A regional correlation of the Albanian terraces based on numerical ages

Few samples have been discarded during our work (Table 2): two 14C samples, that furnished less than 200-year ages in old terraces, were considered as related to the reworking of recent organic pieces. The Carbon quantity of five samples was too small (less than 0.12 mg) to give numerical ages. Two 10Be samples were also excluded from the profile interpretations because one was probably transported by a small tributary and the other one affected by a probable chemical problem during the preparation (Supplementary Information, Appendix 2). Finally, two TL ages published by Lewin et al. [1991] were removed due to their very high uncertainty.

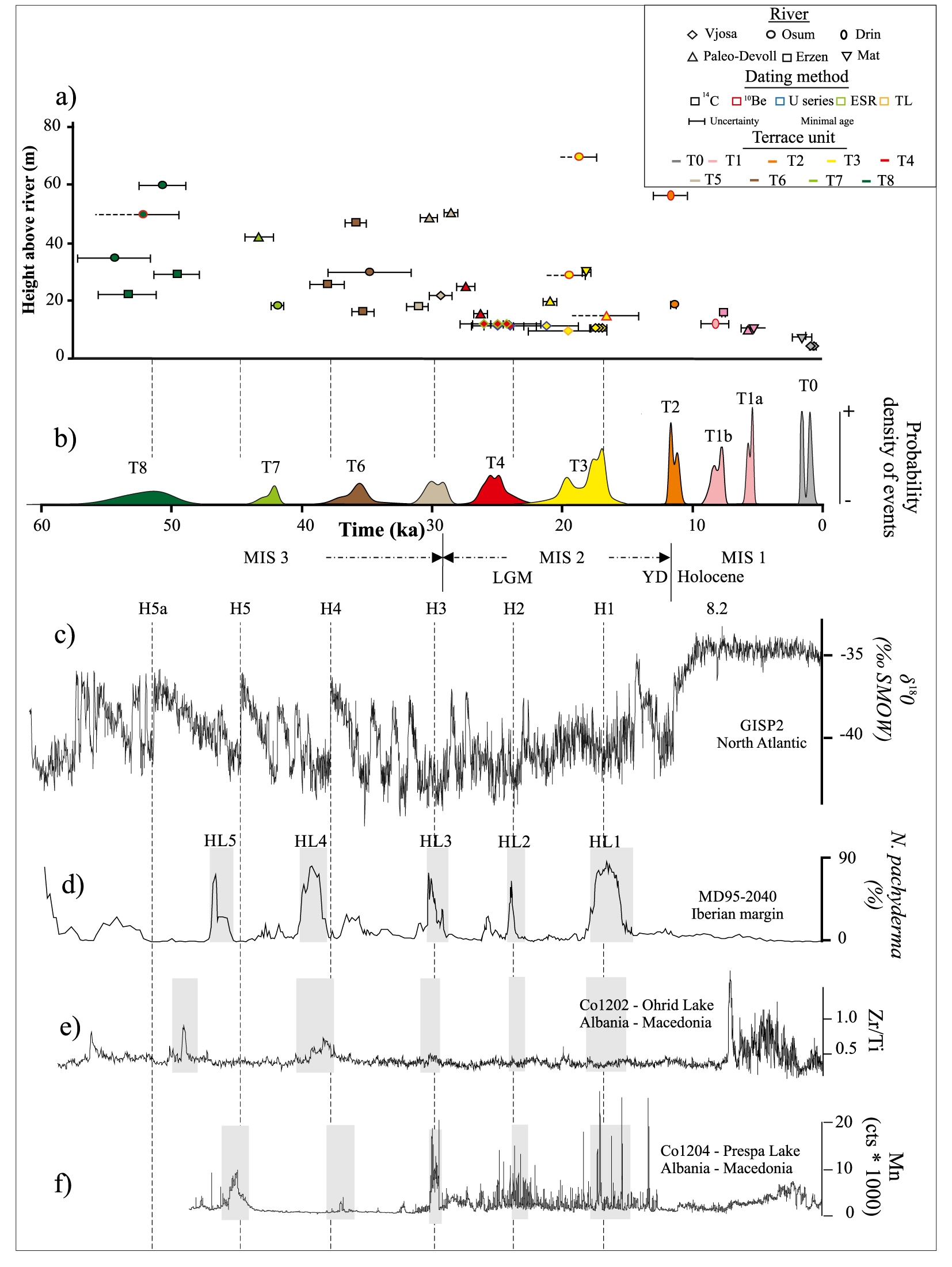

Thirty-one out of the 49 local terrace levels (Tx(river), Figure 4) recognized along the seven rivers were dated, providing a solid framework for a regional correlation (Tx) based on the synchronicity of numerical ages. No simple relationship between altitude and age is observed at the scale of Albania (Figure 9a) due to the variable uplift rate in the Albanian mountains [Guzmán et al. 2013].

To consider the 60 numerical ages younger than 60 ka, a regional probability density curve was obtained from the summation of the individual probability distribution ages [Ramsey 2009], a method already used in terrace chronology studies [e.g. Meyer et al. 1995; Wegmann and Pazzaglia 2002, 2009]. The summation (Figure 9b) shows time periods where the probability of sedimentation is null and ten high probability peaks. These peaks define the ages of T0 to T8 (Table 3, see details of the correlation in Supplementary Information, Appendix 6).

Compilation of the Albanian terrace ages for the last 60 ka (Table 2) and comparison with climatic proxis. (a) Plot of individual ages and their two sigma (95%) probability. Each terrace is represented by a symbol, a contour color and a fill color corresponding to the river, the dating method and the terrace level (regional nomenclature), respectively. The horizontal axis is the terrace age while the vertical axis is the height of the terrace above the present-day river. (b) The regional probability density curve produced by summing the probability distribution of the individual ages; (c) The 𝛿18O record from the GISP2 ice core [Grootes et al. 1993]. (d) The percentage of the cold-water foraminifera N. pachyderma from the Iberian margin [de Abreu et al. 2003]. (e) The paleo-environmental record from Lake Ohrid (Zirconium/Titanium ratio: Zi/Ti) [Wagner et al. 2009]; and (f) the paleo-environmental record from Lake Prespa (Manganese: Mn) [Wagner et al. 2010]. The timings of the Heinrich events (H1 to H5a) are taken from Rashid et al. [2003] and Hemming [2004]. The gray rectangles represent the Heinrich events as identified by the authors of curves (d–f). MIS, LGM and YD stand for Marine Isotope Stage [Cacho et al. 1999], Last Glacial Maximum [Clark et al. 2009] and Younger Dryas [Berger 1990], respectively. Masquer

Compilation of the Albanian terrace ages for the last 60 ka (Table 2) and comparison with climatic proxis. (a) Plot of individual ages and their two sigma (95%) probability. Each terrace is represented by a symbol, a contour color and a fill ... Lire la suite

The ages greater than 60 ka are few in number and the regional T9 to T12 levels are only defined by one or two ages. Eighteen terrace levels are not numerically dated along the various rivers. Their intercalation between dated levels provides a rather good relative age (yellow cells on Table 3) or their elevation relative to the dated terrace levels only provides a poor relative chronology (white cells in Table 3).

5.2. The influence of the paleoclimate on the genesis of Albanian terraces

The comparison of the Albanian terraces ages with climatic proxies [Grootes et al. 1993; de Abreu et al. 2003; Wagner et al. 2009, 2010] is a rather difficult exercise given the uncertainties about the terrace abandonment ages (more than one thousand years) and the short-term fluctuations in the climatic records [less than one thousand years, Ziemen et al. 2019]. A robust criterion could be based on models that link the timing of sedimentation and incision with the temperature, hydrology and vegetation evolutions during a climatic cycle [Bull 1991].

Cold periods in Albania are associated with less precipitation [Kallel et al. 2000; Toucanne et al. 2015] and we consider the classic model for these climatic contexts, where vertical incision is favored by the increase of the transport capacity that occurs at the transition from cold and dry conditions to warmer and more humid conditions [e.g. Fuller et al. 1998; Bridgland and Westaway 2008]. This model has been proposed to define the “cold” terraces in the lowlands of northern Europe [Vandenberghe 2015], to correlate terraces at the Mediterranean scale [Macklin et al. 2002], to interpret terraces in semi-arid conditions [Vassallo et al. 2007] and to interpret the nested terraces in Northern Apeninnes [Wegmann and Pazzaglia 2009] or the western Carpathians [Olszak 2017].

The succession of cold periods followed by rapid warm excursions, could effectively cause the abandonment of most terraces (Figure 9c): T2, T6 and T7 are synchronous with the end of the Younger Dryas, the Dansgaard-Oeschger events number 7 and 11, respectively [Dansgaard et al. 1993; North Greenland Ice Core Project Members 2004]. Furthermore, the abandonments of T8, T5, T4, and T3 (Figure 9b) correlate rather well with the H5a [Rashid et al. 2003], H3, H2, and H1 Heinrich events [Hemming 2004], respectively (Figure 9c). These Heinrich events were already recorded in this area [Wagner et al. 2009, 2010] (gray rectangle on Figure 9d–f).

The ranges of the terrace ages, defined by the 95% probability interval of the summation curve, therefore include the ages of transitions between cold-dry and warm-wet periods. Nonetheless, as the climatic transitions were dated more precisely than the Albanian terraces (less than a thousand years vs. more than a thousand years), our results do not prove the “cold” terrace model of Vandenberghe [2008] and are only in agreement with this model of terrace genesis.

However, while rapid changes during the glacial cycle, such as DO or HE events, can induce the formation of “cold” terraces, the major changes that occur between the glacial and interglacial periods are not generally considered in this model. This is the case of T1 that is not synchronous with a cold to warm transition. Vandenberghe [2008] suggests that, in addition to the “cold” terrace model, deep channels may be very rapidly incised and then filled at the beginning of a warm period. This results in a “warm” unit model [Vandenberghe 2008] and situations of rivers leaving their valley to take another course [Vandenberghe 1993] frequently typify “warm” units [Vandenberghe 2015].

T1 is related to the Holocene climatic optimum and a great aggradation along the Vjoje (Figure 3a) as well as deviations of the rivers at the Cërrik and the Tirana wind gaps (Figure 4 and Figure 8) were recorded during this period. The T1 terrace would therefore be in line with the “warm” unit model [Vandenberghe 2015]. Similarly, the U10(pa), remnant of a valley fill older than the T10 (90–117 ka) overlying unit, may have been deposited during the Eemian interglacial (MIS-5e) stage and could be a “warm” sedimentary unit [Vandenberghe 2015].

6. Conclusions

Geomorphologic studies and new dating have been performed along the Devoll, Shkumbin, Mat and Erzen rivers of Albania (30 14C sites, two 10Be profiles and two 10Be surface sites). A comparison is also made with previous studies along the Vjosa, Osum and Drin rivers. This work has led to a database of 70 ages and a time correlation has been performed between the flights of terraces observed along the seven rivers. It appears that 11 terrace levels have been preserved during the last 200 ka in Albania and this record contains most of the major phases of terrace formation in the Mediterranean region during the last glacial cycle. The exceptional preservation of the succession of Albanian terraces is probably due to the combination of a moderate uplift rate (0.5 to 1 mm/year) and a medium strength of the bedrock lithology (mainly flysch or molasse) specific to this area. During the Holocene, T1 terrace level was recognized, along with the capture of the Devoll River by the Osum River and a tributary deviation away from the Erzen. Eight terraces (T2 to T10) were identified and dated during the last glacial period (MIS 5d to end of MIS 2). For the older periods, amongst the numerous observed terrace remnants, only a unique of T11 was dated at ⩾194 ± 19 ka (MIS 6).

The abandonment of the Albanian terrace surfaces was mainly controlled by climatic variations and was generally synchronous with the interstadial transitions during the last glacial period. This indicates that the threshold necessary for a cold to warmer climatic control for terrace development is reached during interstadial climatic events as short as Heinrich events.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the NATO SFP 977993 and the Science for Peace team for supporting this work. OG thanks the Simon Bolivar University for granting him permission to carry out his doctoral studies. This publication was also made possible through a grant provided by the Institut de Recherche et Developement. We warmly thank the staff of the AMS facility ASTER at the Centre Européen de Recherche et d’Enseignement des Géosciences de l’Environnement (CNRS, France) for technical assistance during the 10Be measurements. We thank one anonymous reviewer and Johannes Preuss for helpful comments.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0