1. Introduction

Glauconite is a green mineral belonging to the family of phyllosilicates neoformed during diagenesis. Glauconite sensu stricto is very close to illite, from a mineralogical and chemical point of view, with the characteristic presence of potassium (K+) and iron (both Fe2+ and Fe3+) ions [Burst, 1958, Odin and Matter, 1981, Stille and Clauer, 1994, Velde, 2014, Huggett, 2021, see the recent synthesis by Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024]. Glauconite is commonly encountered in the form of green grains or pellets and such grains may be referred to as glauconitic grains or glaucony, as suggested by Odin and Létolle [1980]. In what follows, the mineral sensu stricto will be termed by the single word glauconite, the green grains or pellets will be designated by the terms glauconitic grains, and facies rich in glauconitic grains will be termed glaucony, regardless of their exact mineralogical nature [glauconite, glauconitic micas, glauconitic smectites, verdine, etc.; Odin and Matter, 1981]. Since the extensive work of Odin and co-workers, the presence of glauconitic grains has been commonly considered to be a marker of the conditions encountered on continental platforms sufficiently distal to undergo a very low sedimentation rate [Odin and Matter, 1981, Giresse and Wiewióra, 2001, Velde, 2014, López-Quirós et al., 2019, Huggett et al., 2017, Huggett, 2021]. Condensed sedimentation would be required for protracted exchanges between seawater (source of dissolved K) and the authigenic mineral to exist [McRae, 1972, Odin and Matter, 1981, Amorosi, 1995, 1997, Velde, 2014, Föllmi, 2016, Giresse, 2022, Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024]. This classic vision of glaucony began to be complemented at least twenty years ago: it has been shown that glauconitic grains can form in a variety of sedimentary environments where sedimentation rates can even be relatively high [Huggett and Cuadros, 2010, El Albani et al., 2005, Banerjee et al., 2012a,b, 2016a,b, Bansal et al., 2020, 2022, 2023, Wilmsen and Bansal, 2021, Baldermann et al., 2013, 2022, Tallobre et al., 2019, Roy Choudhury et al., 2021a,b, 2023, Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024]. However, it is still frequently taught that glauconite and glauconitic grains are typical of condensed platform environments bathed under mildly reducing conditions to explain the presence of reduced iron (Fe2+) in the crystal lattices of this mineral. This paper reports on recent works showing that it is not a question of setting aside “classical” interpretations of the genesis of glauconite but of illustrating the variety of contexts where it is encountered. In particular, it is evidenced that glauconite can be present very early on the proximal part of detrital platforms and that it can thus witness the conditions at the redox interface (near the sediment-seawater interface). Thus, what are the depositional requirements for such an early formation? Beyond questioning the conditions of formation of glauconite, a wider scale point may be addressed. The stratigraphic record is punctuated with episodes of widespread accumulations of glauconite; does it rely with peculiar events of the Earth’s history? Does it imply some constraints on iron availability? This paper aims to provide some answers, notably stressing on the part played by iron.

2. The classic views

Glauconite is an authigenic phyllosilicate, a member of the green clay minerals family, which is found mainly in marine deposits and which is quite common, both in carbonate sediments and in clastic ones. Its presence is already observed in sedimentary rocks of Precambrian age [Odin and Matter, 1981, Banerjee et al., 2016a, Huggett, 2021, Velde, 1992, Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024]. Its formula is (K,Na)2(Fe3+,Fe2+,Al,Mg)4[Si6(Si,Al)2O20](OH)4. It is commonly accepted that glauconite forms at the sediment-water interface or a short distance below it. Indeed, the authigenic formation of glauconite requires the capture of chemical elements present in the water column, allowing a mineral rich in iron and potassium to develop. These exchanges with seawater require that relative proximity to sea water be respected. It is then logical to consider that a low sedimentation rate is required for the growth of glauconitic grains [Odin and Matter, 1981, Velde, 2014, Huggett, 2021, Rafiei et al., 2023]. Glauconite is also considered to develop from a precursor, most commonly present in the form of an iron-bearing smectite. This precursor evolves towards a glauconite through K+ enrichment [Charpentier et al., 2011, Gaudin et al., 2005]. According to several authors [Odin and Matter, 1981, Baldermann et al., 2013, López-Quirós et al., 2019, Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024], this incorporation could occur over periods of up to 103 years, or even 106 years. The so-called maturity of glauconite is therefore correlated with the quantity of K+ incorporated. Glauconite contains iron present with both valences Fe(II) and Fe(III). This characteristic requires weakly reducing conditions, making it possible to obtain reduced iron simultaneously with oxidized iron. López-Quirós et al. [2019] mention values in the order of 0 mV, as regards the redox potential (Eh), and 7–8, as regards the seawater pH. Xia et al. [2022] report a typical Fe(III)/Fe(II) ratio of 9/1. Decaying organic matter and empty foraminiferal tests or chambers supply the ideal environment for glauconite genesis [McRae, 1972]. More strongly reducing conditions, where iron is entirely in the form of Fe(II), lead to the formation of another authigenic mineral: pyrite [Berner, 1981]. Finally, glauconitic grains are used to date sedimentary deposits, via the K–Ar or Rb–Sr methods [e.g., Vandenberghe et al., 2014, Rafiei et al., 2023, and references therein]. For a long time, the prevailing opinion was that glauconite was mainly formed where precursor clays are present and where the sedimentation rate is low, that is to say, the edge of the continental shelf. In such an environment, glauconitic grains could grow for periods of up to 106 years [Velde, 1992].

3. Classic views called into question

More recently, the spectrum of glauconitic grains formation conditions has gradually expanded. Without denying the previous interpretations, it is now possible to complement them, thanks to several works. An extreme situation is the possible existence of glauconite on Mars [Losa-Adams et al., 2021]. Huggett and Cuadros [2010] report onshore, non-pellet glauconite formation. El Albani et al. [2005] observed glauconite formed in extremely shallow environments (lagoonal setting). Wilmsen and Bansal [2021] and Bansal et al. [2023] demonstrated the formation of glauconite in shallow (nearshore) conditions during the Cenomanian. At the other end of the depth spectrum, Porrenga [1967] already mentioned long ago the possibility that glauconite could form at depths between 30 and 2000 m; see also Duplay et al. [1989]. However, we must wait for much more recent work for the formation of glauconite in deep marine environments to be discussed [e.g., Baldermann et al., 2013, 2022, Tallobre et al., 2019, to mention a few papers]. In other words, the formation of glauconite is now identified in a wide range of sedimentary environments. Furthermore, other recent work has called into question the length of time required for glauconite and glauconitic grains to form. Meunier and El Albani [2007] discussed this aspect, showing that it can sometimes be difficult to imagine that mature glauconitic grains could have formed during times whose duration would have exceeded 100,000 years (or even more), taking into account the sedimentary environments where glauconite is observed. The difficulty comes from sedimentation rates which cannot reasonably have been close to zero for so long. The authors reconciled the established “dogma” and their observations by concluding that glauconite could have formed quickly and that these episodes of rapid glauconitization could have been repeated over long periods of time, between 100,000 years and 106 years. Another way to smooth down the apparent paradox of the duration of formation is to consider winnowing. Winnowing, also termed washing, is the selective sorting, or removal, of fine particles by (wind or) current action, leaving the coarser (denser) grains behind [Bates and Jackson, 1987]. In proximal settings, recurrent storms or the action of marine currents could stir and sort the sediment, driving away lighter particles and concentrating in situ denser ones such as glauconitic grains. For instance, Giresse [2022] and Föllmi [2016] mention recent and ancient situations where winnowing must be suspected.

More recently, Wilmsen and Bansal [2021] and Bansal et al. [2023] demonstrated the early formation of glauconite in environments with a high sedimentation rate. The duration of glauconite formation can be nothing but short in such environments. Föllmi [2016] and Rubio and López-Pérez [2024] state that all the examples they reports on in their respective synthesis indicate that condensation may play a role in the formation and concentration of verdine and especially glauconite, but not in all cases, in contrast to earlier views [e.g., Van Houten and Purucker, 1985].

To conclude, the knowledge acquired recently shows that the formation of glauconite is more ubiquitous than what previous work had defined: from the shallowest shoreface to the deep marine setting, even including (extra)terrestrial environments (soils, lagoons). In addition, recent progress shows that glauconite can form in shorter periods of time than was usually accepted for these authigenic minerals.

4. What conditions the abundance of glauconite?

In light of the observations reported above, it is logical to ask the following question: if the formation of glauconite and glauconitic grains can be more rapid and more generalizable than previously assumed, why is glauconite not more abundant in the stratigraphic record? What could have been the limiting factors? In vitro, glauconite was observed to form within a few months, in solutions containing Si, Al, K and Fe at room temperature, provided iron was abundant enough [Harder, 1980]. This abiotic process requires specific redox conditions: reducing enough to allow iron to be mobile and to reach relatively high concentrations, and oxidizing enough to allow iron hydroxides to form and react with dissolved elements, ending with the formation of glauconite [Harder, 1980]. This delicate balance could be the whole crux of the story: shallow marine sediment most often contain organic matter spanning a wide range of concentrations. The organic-product decay usually induces the development of bacterially mediated sulfate reduction reactions. The HS− ions thus released will favor pyrite precipitation and prevent glauconite formation. Therefore, the formation of glauconite could be rather quick and easy in vitro, but, in vivo, it is impeded by usual environmental conditions: too little reactive iron, to much sulfide, which can explain why glauconite is not as omnipresent as pyrite in the geological record.

What is meant with the expression: “reactive iron”? It must be distinguished between “reactive” iron, which can be involved in chemical reactions, and “inert” iron (firmly bound within crystal lattices), which is poorly or not reactive during sediment early diagenesis [e.g., Canfield et al., 1992, Raiswell and Canfield, 2012, Poulton, 2021, Vosteen et al., 2022]. Following the seminal work by Canfield [1989], geochemists usually define reactive iron as iron (oxyhydr)oxides that can be reductively dissolved by sodium dithionite, or, more broadly, by HCl [see Burdige, 2006, and references therein]. In any case, reactive iron is considered to be reactive toward sulfide ions. This definition is quite formal, and in the present work, reactive iron will be considered to be the part of the iron inventory capable of being involved in chemical reactions and/or authigenic-mineral growth or formation. That is to say that reactive iron is not locked inside mineral structures or lattices, but may be desorbed, exchanged or released from, or out of, organic-mineral complexes, clay-organic complexes, clay-mineral (surfaces). It can also result from the bacterially mediated reduction of lowly soluble, iron oxides that are released from emerged lands. They may come in a soluble, reduced form, together with ground discharge of oxygen-poor freshwater at the land-sea boundary [Burdige, 2006, Raiswell and Canfield, 2012].

4.1. Iron as a limiting factor

Many authors have examined the origin of the chemical elements necessary for the authigenic growth of glauconite: K+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Al3+, Si4+ [Odin and Matter, 1981, Berner, 1981, Meunier and El Albani, 2007, Roy Choudhury et al., 2021a, López-Quirós et al., 2019]. These authors consider that smectite constitutes the most common precursor, providing silicon and aluminum. They also conclude that seawater is unlikely to provide the necessary iron but does provide potassium and that detrital particles can provide Fe, K and Si, for shallow water deposits [Sánchez-Navas et al., 1998, López-Quirós et al., 2019, Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024]. These detrital minerals can be Fe(III)-oxides or Fe-kaolinite. The elements K, Si, Fe, and Al have contrasting residence times and concentrations in present-day seawater, as shown in Table 2. This table indicates that potassium is relatively abundant and stable in the current ocean while iron is a limiting factor, with a residence time counting in tens or hundreds of years according to the authors, and its concentration in the water of sea is measured in picomol per kg only. It is well understood that the precipitation of authigenic iron minerals is conditioned by the availability of reactive iron, that is to say, forms of minerals from which iron can be released over short periods of time. Depending on the mineralogical nature of the support, iron is released at very variable speeds [Canfield, 1989, Canfield et al., 1992]. In shallow environments (shoreface to offshore), reactive iron is mainly delivered from the emerged land, following the leaching of continental masses [Canfield et al., 1992, Raiswell and Canfield, 2012, Bansal et al., 2020, Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024, and references therein]. Therefore, the authigenesis of glauconite in proximal environments is directly linked to the amount of reactive iron from the emerged land (the aspects of glauconite formed at great depths are not treated here but it may be mentioned that Duplay et al. [1989] observed the formation of glauconite at low temperature within ocean-flooring basalt where halmyrolyse released solubilized iron). These iron inputs can be transported by rivers and winds [Raiswell and Canfield, 2012] but in proximal environments, fluvial inputs mask wind inputs which are less quantitatively abundant. The main factors favoring iron inputs to shallow marine environments are volcanic episodes or very hydrolyzing climatic episodes [hot and humid climates; Shoenfelt et al., 2019, Bansal et al., 2020, Longman et al., 2022, Vosteen et al., 2022, Schunck et al., 2023, to mention a few recent papers]. Furthermore, the proximity of emerged lands plays a crucial role for the presence of iron [Burdige, 2011]. Indeed, the iron resulting from leaching of the emerged land is very quickly oxidized in seawater, which drastically reduces its solubility (thence its short residence time). Consequently, the quantity of reactive iron decreases rapidly as we move away from the sources of input.

Concurrently, shallow-marine environments are highly sensitive to sea-level variations that condition the dynamics of the sediment distribution. Beyond the situations of the Boulonnais evoked below, and despite the exceptions identified in the syntheses by Föllmi [2016] and Rubio and López-Pérez [2024], the fact remains that in such depositional settings, glauconite accumulations are most frequently associated with episodes of condensation; in addition, a number of such condensed accumulations are in turn associated with sea-level rises, as stated by these authors. Therefore, land-derived reactive-iron supply, plus transgression-induced episodes of condensed sedimentation, are expected to favor the formation of glauconite-rich sediments. However, conversely, not all episodes of transgression in continental platform environments result in deposits rich in glauconite [and this did not escape the analysis of Föllmi, 2016]; these are therefore often necessary but not sufficient conditions. The hypothesis of a limiting factor which would be the availability of reactive iron can therefore be formulated. Why iron rather than another element also included in the chemical composition of glauconite? Because iron is the element that is the most difficult to maintain in solution or in a reactive state compared to the others (as recalled above). In addition, the redox conditions cannot be reducing, otherwise pyrite will form instead of glauconite. Consequently, it is suggested here that reactive iron could be a key factor limiting the genesis of glauconite because of its availability being so delicate to maintain, as reminded by Poulton and Raiswell [2002], and Kendall et al. [2012].

Baldermann et al. [2022] argue that large-scale, glauconitic grain formation in shallow as well as deep marine settings is an important iron sink that is currently underestimated. This point of view is very interesting since iron is a bio-essential element; therefore, its retention in authigenic minerals could impact or have impacted marine productivity. Developing this point upstream of the reaction chain, we could say that if glauconitic facies are quantitative iron traps, this implies that, previously, reactive iron must have been present in significant quantities in the marine environment. We will therefore examine the contexts where iron inputs could have allowed or favored the formation of glauconitic facies. These different cases will then be compared with the deposits rich in glauconitic grains from the Boulonnais area.

4.2. Iron delivery to shelfal environments

Regional-scale glauconite accumulations require regional-scale iron supplies to seas. Such supplies to shelfal environments are attributed to the volcanic activity or the weathering of emerged lands, as said above. Föllmi [2016] listed the large accumulations of glauconite through the Earth’s history. As volcanoes cannot be systematically invoked for each glauconite concentrations, it must be concluded that continental weathering could have triggered such regional-scale glauconite accumulations. Weathering can be stimulated by hydrolyzing climate conditions or orogenies exposing fresh rocky material, or both. In other words, with a bit of hindsight, glauconitic facies may be the result of large-scale, paleoenvironmental and geodynamic (tectonic) changes. Furthermore, it may also considered to be an important archive, allowing geochemical proxies of long-term processes in the oceans to be traced, e.g., changes and shifts in marine currents and mixing of ocean waters [see discussion about condensed sedimentation in Föllmi, 2016].

At a local scale, an additional source of reactive iron can also be mentioned: cold seep fluids, often rich in methane (CH4) or other forms of organic matter [e.g., Lemaitre et al., 2014, Hong et al., 2020, Ta et al., 2024]. Incidentally, beyond shelfal environments, (hot) hydrothermal fluids can also release iron in oceanic settings. In addition to dissolved iron, cold seep fluids are also reported to release dissolved potassium [Olu et al., 1996, Suess, 2014, Wang et al., 2017, Zhang et al., 2022]. That is to say that cold seep sites are places where the “ingredients” of glauconite are available and where redox conditions may not be reducing. For the latter point, see discussion in the recent paper by Haase et al. [2024] and references therein. To sum up, cold seep sites are places where conditions may be necessary if not sufficient for glauconite to form.

Lastly, some works suggest that anoxic sediments contribute some release of iron to the sediment-water interface and, possibly, to the bottom waters [conditions termed ferruginous; e.g., Lyons and Severmann, 2006]. Under reducing conditions, iron would be solubilized in the Fe2+ state and could migrate upward through the sediment and even escape from it via diffusion and pore water expulsion [e.g., Fortin and Langley, 2005, Lyons and Severmann, 2006, Burdige, 2011, Pasquier et al., 2022]. Nevertheless, in marine platform environments with normal organic productivity, the sediment is usually the place for an intense bacterial activity, dominated by sulfate-reduction reactions. These reactions follow two ways: organoclastic sulfate reduction and sulfate-dependent anoxic oxidation of methane [e.g., Jørgensen, 2019, Jørgensen et al., 2019, Huang et al., 2022]. Either way leads to the transformation of dissolved sulfate into soluble sulfide. Reduced iron has so high an affinity toward sulfide ions that iron is more likely to be fixed inside the sediment in the form of iron sulfides (such as pyrite) than to reach and rise above the sediment-water interface. In other words, sediments rich in organic matter, stimulating bacterially mediated decay of organic products and favoring sulfate reduction reactions are a priori not suitable for glauconite growth. Nevertheless, the remineralization of moderate to low amounts of marine organic matter, or the presence of terrestrial, recalcitrant, organic matter, resisting extensive decay, could lead to limited dissolved-O2 consumption and create redox conditions prone to glauconite formation.

5. The case of the Boulonnais

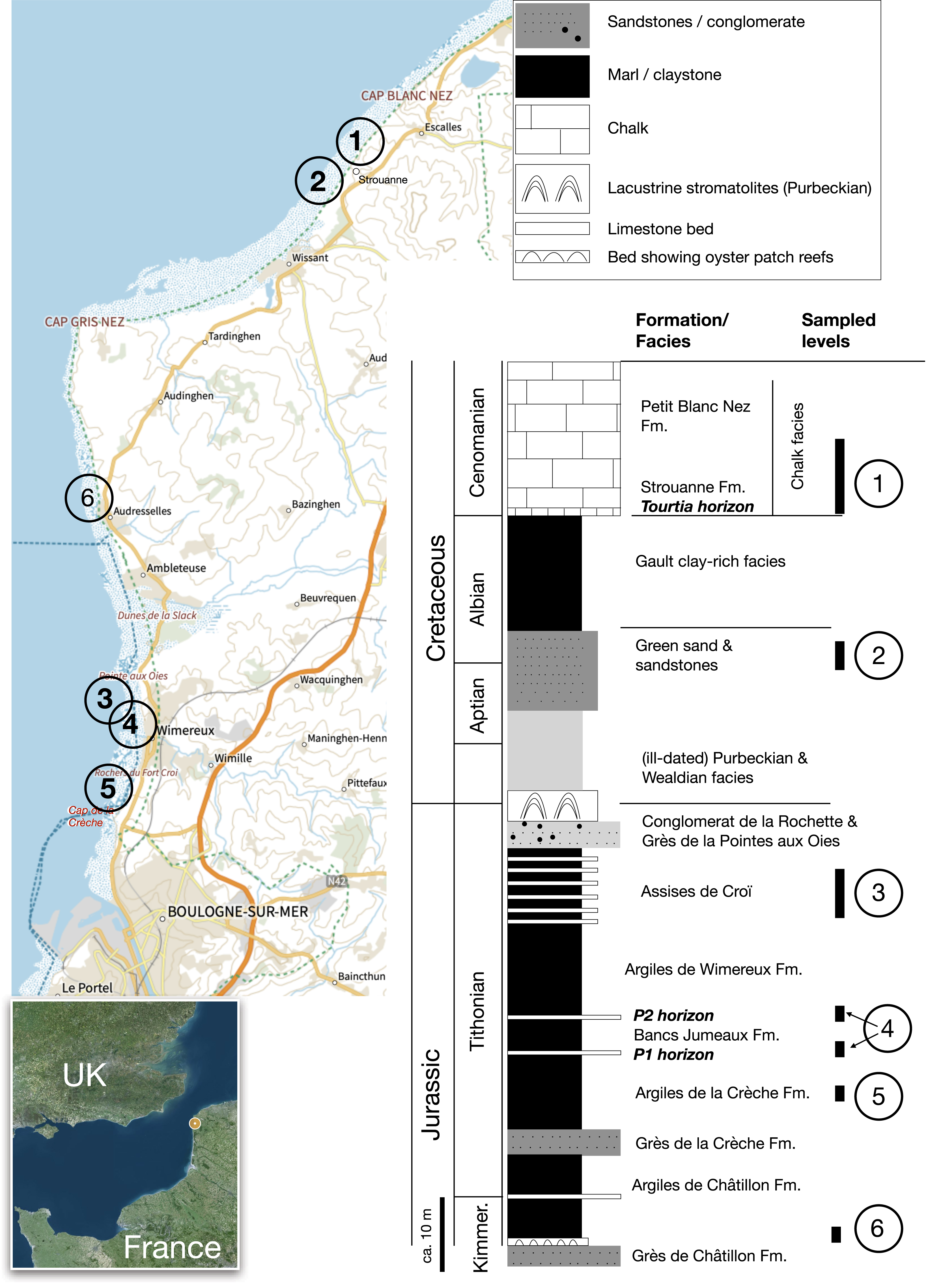

In France, the Upper Jurassic and Cretaceous geological formations in Boulonnais (French coastline of the Strait of Pas-de-Calais, in the English Channel) show levels sometimes rich in glauconitic grains [Mansy et al., 2007]. Geological formations containing such levels are shown in Figure 1 and listed in Table 1. Their detailed studies can be found in the corresponding papers, indicated in this table. The Upper Jurassic formations (Kimmeridgian and Tithonian) were deposited on a shallow continental platform (shoreface-lower offshore) which terminated the London-Brabant Basin to the east [Mansy et al., 2003]. The stratigraphy of the Late jurassic-Cretaceous sequence can be summarized as follows. The Jurassic deposits consist essentially of a succession of sandstone formations and marl formations. Among them, some contain levels rich in glauconitic grains. The transition between the Jurassic and the Cretaceous is accompanied by a prolonged emergence of the region (Purbeckian facies then depositional gap). Marine sedimentation will only resume in the Aptian–Albian with terrigenic deposits (glauconitic sandstones) topped by Upper Cretaceous Chalk [Mansy et al., 2007]. The Cenomanian chalk, deposited during the great transgression of the Upper Cretaceous, is marked at its base by a very dark gray limestone level, this color being due to a large abundance of glauconite (around 44% of the weight of the rock). This level is sometimes called Tourtia in the literature [Amédro and Robaszynski, 1999]. This basal level is overcome by much finer glauconite-rich levels, the presence of which is associated with periods of sea level rise, finding their place in a pattern of sequential stratigraphy [Amédro and Robaszynski, 1999, Amorosi and Centineo, 2000].

Location of the sections sampled alongshore the Boulonnais, Strait of Pas de Calais, English Channel. The numbers on the coastline refer to the simplified stratigraphic column. Map after the SHOM website (Service Hydrographique & Océanographique de la Marine; https://www.shom.fr/).

Short description of the levels sampled in the stratigraphic succession of the Boulonnais

| Age | Geological formations | # in Figure 1 | Levels rich in glauconite in Boulonnais | Location (see Figure 1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cretaceous | Cenomanian Chalk | 1 | Glauconious chalk at the lowermost part of the formation, beginning with the so-called Tourtia bed, rich in glauconite | Beach between Strouanne and Cap Blanc Nez | |

| Aptian–Albian sandstones | 2 | Dark-colored sands and sandstones visible at low tide | Strouanne Beach | ||

| Jurassic | Tithonian | Assises de Croï | 3 | Alternating carbonate levels and marly interbeds | Sampled at Pointe aux Oies (North Wimereux), pictured at Rochers du Fort Croï (South Wimereux) |

| Bancs Jumeaux | 4 | P1 & P2: phosphate- and clastic-rich carbonate levels, at the base and top of the formation | South to Pointe aux Oies (place called Pointe de la Rochette) | ||

| Argiles de la Crèche | 5 | Silty marls at the very base of the formation | Rochers du Fort Croï (South Wimereux) | ||

| Kimmeridgian | Argiles de Châtillon | 6 | Coquina beds at the Kimmeridgian-Tithonian boundary | North of Audresselles (Cran du Noirda) | |

| Argiles de Châtillon | 6 | Oyster patch reefs at the base of the formation (the Boundary Bed, Kimmerdigian) | North of Audresselles (Cran du Noirda) |

Concentrations in seawater and residence times of silicium, aluminum, iron and potassium

| Fe | Al | Si | K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 26 | 13 | 14 | 19 |

| Atomic weight | 55.847 | 26.98154 | 28.0855 | 39.0983 |

| Average concentration in ocean | 540 pmol/kg | 1.11 nmol/kg | 100 μmol/kg | 10.2 mmol/kg |

| Residence time | 50–500 yrs | 200 yrs | 20,000 yrs | 12,000,000 yrs |

Data from Bruland [1983] and Byrne et al. [1988] collected on the website of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI): https://www.mbari.org/know-your-ocean/periodic-table-of-elements-in-the-ocean/summary-table/.

5.1. Cretaceous deposits

The Mesozoic geological formations of the Boulonnais illustrate the complexity or, at least, the diversity of the conditions of formation of glauconite. The largest-scale phenomenon is probably the presence of green sands (also written greensands) of Aptian–Albian age. They may contain glauconite but also other types of green minerals often referred to with the words verdine and glaucony [Föllmi, 2016, Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024]. Such green sands and sandstones are reported over a wide array of distribution through the Cretaceous world but, regarding the geographical location of the present study, some major, regional-scale, accumulations of green sands may be mentioned in England, Germany, France and the North Sea [e.g., Owen, 1969, Triat, 1983, Robaszynski and Amédro, 1986, Hartley, 1995, Lehmann, 2013]. This remarkable period of deposition green sands is accounted for by the conjunction of two phenomena: (1) the resuming marine sedimentation, related to an incipient eustatic sea-level rise, and (2) a climate favoring continental weathering, therefore, iron release to the seas [Schouten et al., 2003, Dumitrescu and Brassell, 2006, Gale et al., 2008, Mutterlose et al., 2010, 2014, Corentin et al., 2020, Deconinck et al., 2021, Blok et al., 2022, Caillaud et al., 2022, Jia et al., 2022]. This period of time witnessed the development of epicontinental seas. The relatively shallow depth of deposition must have favored the oxygenation of water masses. In addition, the coarse-grained sand deposits prevented or, at least, hampered the development of anoxic conditions within the sediment. Thus, the redox conditions were probably not reducing, therefore, preventing pyrite accumulations to take place, in spite of the abundance of reactive iron. Instead, glauconite could develop widely becoming the distinctive mark of the sand and sandstone of mid-Cretaceous in shelfal environments.

Later on, the eustatic sea-level rise kept on during the Cenomanian and the worldwide development of epicontinental seas witnessed the deposition of the chalk facies over large surfaces [Hancock and Kauffman, 1979, Haq, 2014, An et al., 2017, Le Callonnec et al., 2021]. In France (and England), the base of the Cenomanian chalk is rich in glauconite. The very base (called Tourtia) is made of more than 40 wt% of glauconite [Tribovillard et al., 2021] and is overlain by thin, recurrent, glauconite-rich seams, each of them being related to small-scale fluctuations of the sea-level [Robaszynski and Amédro, 1986, Amorosi and Centineo, 2000]. The chalk is characterized by the overwhelming accumulation of coccoliths. The proliferation of small-dimension phytoplankton (e.g., coccolithophorids versus diatoms) is the sign of oligotrophic marine conditions [Chester, 2000]. In other words, the epicontinental seas of that period of time must have known low-production conditions [Mutterlose and Bottini, 2013, Le Callonnec et al., 2021]. Again, the sediments, lacking abundant sedimentary organic matter, developed redox conditions compatible with glauconite formation, but not with pyrite [except for nodules of later diagenetic origin; Rickard, 2012].

5.2. Jurassic deposits: condensed sedimentation

Contrary to the Cretaceous deposits, the Late Jurassic ones are rich in clay minerals. Such land-derived minerals are considered to be good carrier phases for adsorbed reactive iron; in addition Fe-rich clays (e.g., smectites) may release iron into the pore waters through diagenesis [Canfield, 1989, Kendall et al., 2012]. Furthermore, the Jurassic deposits accumulated on a shallow ramp close to the eastern end of the Weald-Boulonnais Basin [Mansy et al., 2003], that is, close to the sources of land-derived reactive iron [e.g., Jilbert et al., 2018, Herzog et al., 2020]. In other words, iron may have not been the limiting factor with regard to glauconite or pyrite formation. The growth of authigenic minerals was thus directed towards glauconite or pyrite, depending on the redox conditions at the sediment-water interface or a short distance below. This alternative is illustrated by what is observed with the Bancs Jumeaux Fm. (Tithonian). The P1 and P2 levels, corresponding to winnowed, probably erosional, surfaces are rich in glauconite, whereas the marlstones in-between are rich in abundant, large-size, pyrite framboids and polyframboids [Tribovillard et al., 2008, 2023a,b]. The condensed sedimentation of the P1 & P2 levels [Deconinck and Baudin, 2008] favored the formation of glauconite whereas the fine-grained, clay-rich, sediments of the marlstones favored the development of micro-niches or micro-environments where the conditions were reducing, therefore favoring the formation of large-dimensioned (poly-) framboids of pyrite [Tribovillard et al., 2008].

Finally, the Assises de Croï Fm., with glauconite-rich, alternating, carbonate beds and marly interbeds, is also associated with condensed sedimentation [Deconinck and Baudin, 2008] but with no occurrences of seep sites being identified. This rather thin formation (about ten meters) is covering several ammonite zones [Albani, Glaucolithus and Okusensis pro parte; Townson and Wimbledon, 1979]. In this case, the presence of iron must have been owing to the proximity of the shore and associated fluvial inputs [Mansy et al., 2007], and the early diagenetic growth of glauconite must have been owing to the condensed sedimentation: well-sorted populations of quartz grains suggest a hydrodynamic activity such as winnowing [Tribovillard et al., 2023a,b, submitted].

5.3. Jurassic deposits: iron supply from seep sites

The transitional level separating the Grès de Châtillon Fm. and the overlying Argiles de Châtillon Fm. (Kimmeridgian) nested numerous oyster patch reefs. The reefs developed upon cold-fluid seeps associated with synsedimentary fault movements [Hatem et al., 2014, 2016]. To account for the abundant authigenic glauconite associated with the oyster patch reef, a possible link between iron, oyster reefs and glauconite was evoked by Tribovillard et al. [2023a,b] but with no mention of iron being possibly supplied with seeping fluids close to the vents on the sea floor [Lemaitre et al., 2014, Hong et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2022]. Thus, here too, a potential source of iron, namely, the seeping fluids, is associated to the presence of glauconite. Regarding cold seep sites of about the same age, the well-known “pseudo-bioherms” of Beauvoisin [southeastern France; Gaillard et al., 1992, Peckmann et al., 1999, Tribovillard et al., 2013, Gay et al., 2019, 2020] also yield authigenic glauconite, as observed by Gaillard [1983]. Regarding much younger objects, Han et al. [2004] observed abundant glauconite grains associated with seep-site carbonates offshore Costa Rica but they did not evoke a genetical link. The same is true with Himmler et al. [2015] with seep carbonates of the Arabian Sea. Zhang et al. [2022] examined the role of the iron released at seep sites during the Last Glacial Maximum in the South China Sea. They explained how the iron was reductively dissolved and trapped in the form of pyrite through bacterially mediated reactions of sulfate-dependent anoxic oxidation of methane. Meanwhile, part of the iron supply was consumed by glauconite growth in dead-foraminifer chambers.

Thus, examining the influence of reactive iron supply upon glauconite formation leads us to suggest that cold seep sites could be places favorable to the formation of this authigenic mineral. Apart from supplying reactive iron, such sites are not known to experience particularly low sedimentation rates nor to endure winnowing currents. Consequently, it may be postulated that glauconite growth must be relatively rapid in such settings. To test the hypothesis formulated here, glauconite must be looked for, close to the seep vents as well as at some distance, to observe a possible gradient in abundance. Modern, underwater, sites are not convenient for trying to observe such mineral gradients in situ and fossil, on-land, seepage zones are easier to investigate. To the best of our knowledge, such a gradient has not been reported in the literature, perhaps because no one tried hitherto to observe it.

5.4. Partial conclusion

The Upper Jurassic and Cretaceous deposits of the Boulonnais correspond well to the range of situations where reactive iron is brought into the marine environment from emerged lands (rivers and groundwater discharge) or the seabed (seepage). Large-scale climatic and tectonic (transgressions) events affecting the Tethyan realm during the mid-Cretaceous times led to wide-scale accumulations of greensand-type deposits (Aptian–Albian sands and base of the Cenomanian chalk formation, in the Boulonnais). Regional/local-scale factors, such as the hydrographic network, the proximity of the coastline, the occurrence of marine currents, led to medium-scale accumulations of glauconite-rich sediments (e.g., the Bancs Jumeaux and Assises de Croï stratigraphic formations). Finally, localized sources of iron-rich seeping fluids such as vents or pockmarks correspond to places where glauconite is observed (the transition level between the Grès de Châtillon and Argiles de Châtillon formations, that yields numerous oyster patch reefs).

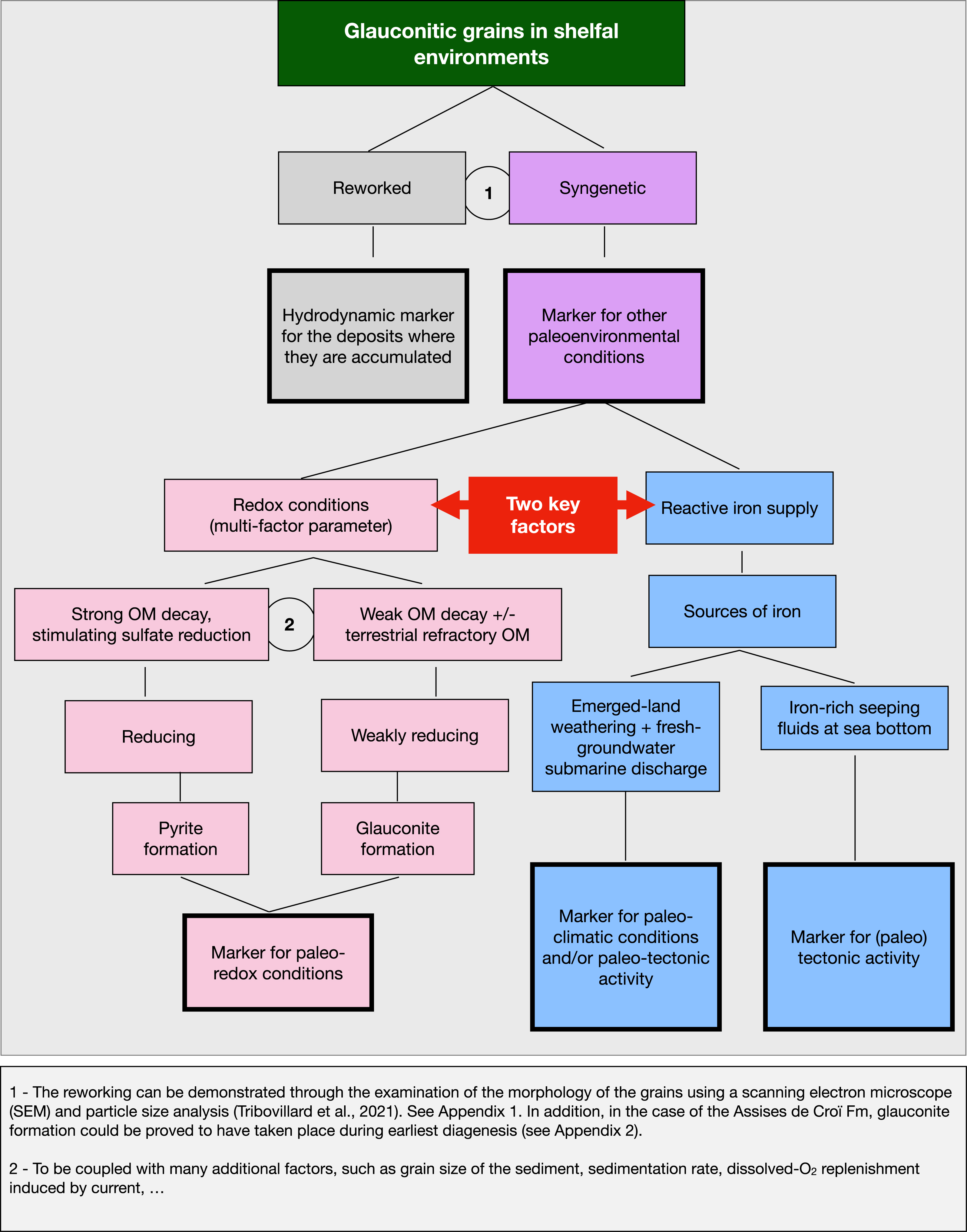

6. Conclusion: a model using glauconite as a tool for paleoenvironmental reconstructions

This examination of the various conditions in which glauconite could form in relatively shallow, shelfal, environments illustrates how much this authigenic mineral is impacted by the environmental context: glauconite is a multi-scale sensor. Since it appears that glauconite can form relatively easily, why is it not more abundant or more frequent in the stratigraphic record of sedimentary basins? The answer to this (somewhat provocative) question can be reduced to two essential factors: redox conditions and the availability of reactive iron, implying that the role played by the duration of the process can be minimized. Furthermore, significant accumulations of glauconite require massive iron inputs. From these statements, an integrated model of the use of glauconite as a tool for paleo-environmental reconstructions can be proposed (Figure 2). As a preliminary remark, let us recall that all the work presented here is based on the observed presence of glauconite sensu stricto and it cannot be claimed that the conclusions put forward here are necessarily valid for sedimentary deposits containing other types of green minerals (verdine, berthierine, glauconitic smectites, etc.). To be used as a paleoenvironmental tool, glauconite grains must not be reworked, and they must have formed at the sediment-water interface or the closest possible to it. Regarding the Boulonnais, the two points are discussed in the Appendices A and B, herein below. To conclude, glauconite can be envisioned as a multi-dimension sensor for paleoenvironmental reconstructions.

Glauconite as a tool for deciphering paleoenvironmental conditions.

Declaration of interests

The author does not work for, consult, own or receive funding from any organization that would benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their sponsoring research organizations.

Funding

This work was supported by INSU, as part of the Tellus Syster research program.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Monique Gentric (LOG) for administration and the Earth Science Department of the Faculty of Sciences & Technologies of the University of Lille for its support. Thanks to the editorial and technical team of the C. R. Geoscience journal.

Appendix A How to know whether glauconite is autochthonous or reworked?

The reworking can be demonstrated in two complementary ways: the morphology of the grains observed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) and particle size analysis [Tribovillard et al., 2021]. The Boulonnais formations studied here almost all present glauconite and quartz (except certain chalk levels from which quartz is absent). These two minerals are extracted and separated into pure phases after decarbonation with HCl and magnetic separation using a Frantz isodynamic apparatus. Each of the two phases is then analyzed with a Malvern Mastersizer device to obtain the particle size distribution [details in Tribovillard et al., 2023a,b]. Quartz is always terrigenic while glauconite can be “terrigenic” (that is, reworked) or autochthonous (synsedimentary, non reworked). Additionally, quartz and glauconite have comparable densities. Therefore, the grain size distribution curves are similar when both minerals are terrigenic, with a unimodal distribution exhibiting good sorting. On the other hand, if the authigenic glauconites are autochthonous, the respective curves of quartz and glauconite are contrasting and the glauconite curves may be plurimodal and the sorting is significantly worse. Thus, in the case of Boulonnais, it was possible to show that the Jurassic levels characterized by the presence of oyster reefs associated with cold seeps of hydrocarbons [Hatem et al., 2014, 2016] were kinds of glauconite factories. This glauconite is observed in the oyster patch reefs themselves as well as in the tempestites they nourished [Tribovillard et al., 2023a]. Similarly, the glauconites of the Assises de Croï Fm. have been proved to be autochthonous [Tribovillard et al., 2023a,b].

Appendix B

With the help of isotopic ages, numerous papers showed that glauconite growth may be quite long, even at the geological scale, as exposed above. However, this rule is not absolute. In the Boulonnais, the Assises de Croï Fm. yields an alternation of limestone beds and marly interbeds. Both facies contains glauconite that was identified as autochthonous and synsedimentary [Tribovillard et al., 2023a]. The nodular, rather contorted, limestone beds were formed during diagenesis, based on stable isotope composition. As they have been bioturbated, it was inferred that the beds were formed during early diagenesis, while the sediment was still rather soft and hosting dwelling in-fauna. The early-formed carbonate objects contain glauconite that was evidenced to pre-date the precipitation of the carbonates nodules and beds [Tribovillard et al., 2023a]. Therefore, glauconite grew during the earliest stages of diagenesis. This is a relative chronology and, as everybody knows, the word early does not necessarily implies short time, especially if winnowing currents affected the sea bottom [discussion in Giresse, 2022]. Whatever, being formed during earliest diagenesis, glauconite was a witness of what was occurring on the sediment-water interface or just below it.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0