1. Introduction

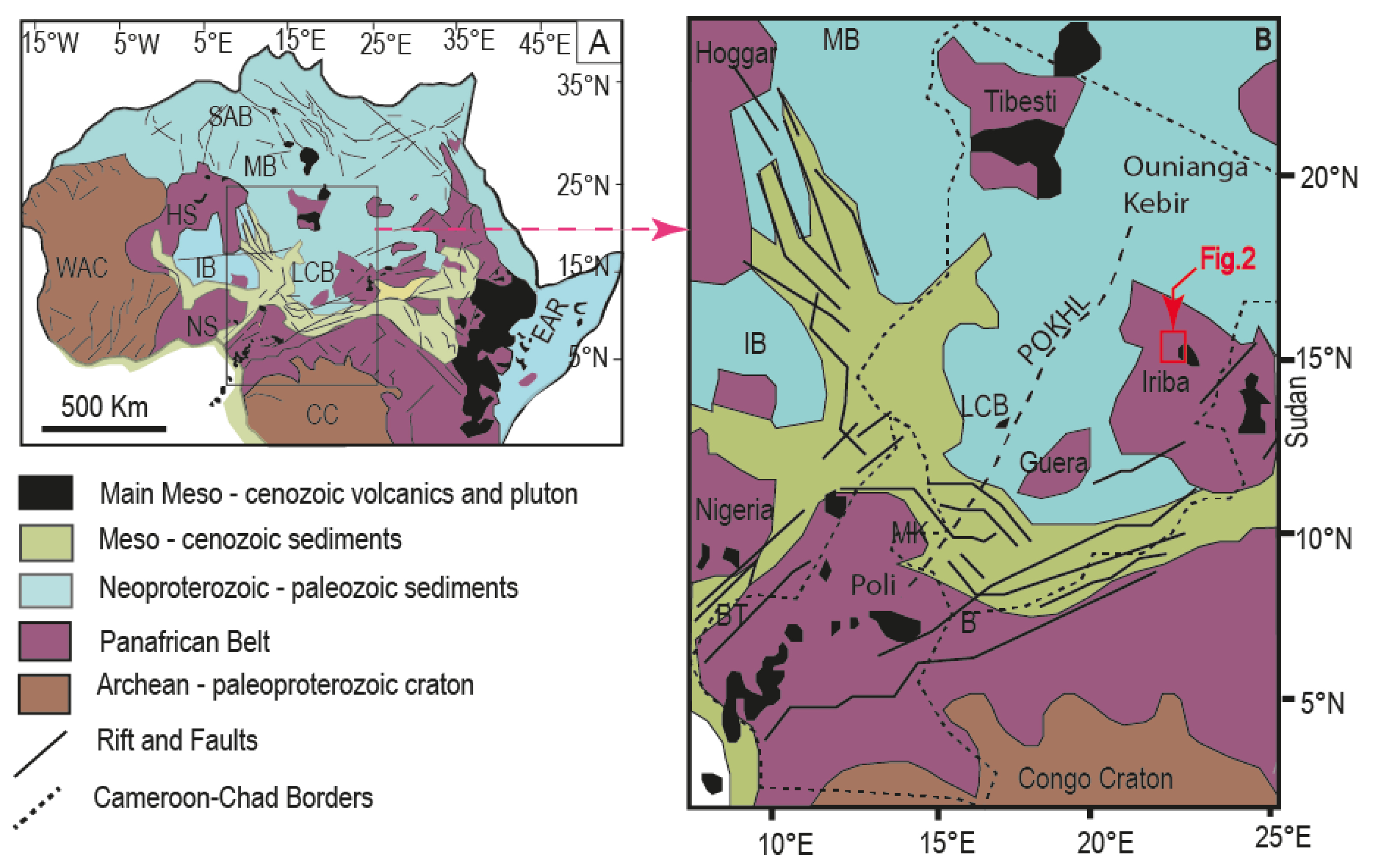

Alkaline magmatism, typical of intraplate environments including oceanic islands, continental rifts and intracontinental volcanoes, is generally the consequence of melting of peridotite in presence of CO2 [Wyllie, 1977, Dasgupta et al., 2007, Baasner et al., 2016], or of recycled oceanic crust [Green, 1973, Chase, 1981, Hofmann et al., 1986], or of metasomatized lithosphere [Halliday et al., 1995, Niu and O’Hara, 2003, Pilet et al., 2008]. Central Africa is made of the composite Archean to Palaeoproterozoic West Africa and Congo cratons bordered by Pan-African belts and Variscan orogenic belts [Figure 1; Bessoles and Trompette, 1980, Nzenti et al., 1988].

(A) Tectonic Map of Africa: Location map of the Cameroon Volcanic Line (CVL). The main geologic features of Africa are indicated. (B) Structural map of Central Africa Rift System [modified after Kogbe, 1981, Milesi et al., 2010] showing the Cameroon Volcanic Line (CVL) and its extension in chad. The names of the main Early Cretaceous intracontinental rifts are indicated. SAB = Sud Algerian Basin; MB = Murzuk Basin; IB = Iullemeden Basin; LCB = Lake Chad Basin; BT = Benue Trough; MK = Mayo Kebbi; B = Baïbokoum; WAC = West African Craton; CC = Congo Craton; HN = Hoggar Shield; NS = Nigerian Shield; EAR = East African Rift; POKH = Poli–Ounianga–Kebir heavy [Louis, 1970]. Masquer

(A) Tectonic Map of Africa: Location map of the Cameroon Volcanic Line (CVL). The main geologic features of Africa are indicated. (B) Structural map of Central Africa Rift System [modified after Kogbe, 1981, Milesi et al., 2010] showing the ... Lire la suite

The published petrological data from the Cameroon Volcanic Line (CVL; Figure 1A) document a typical bimodal series, marked by abundant mafic and felsic lavas and relatively sporadic occurrence in intermediate terms such as mugearites and benmoreites [Marzoli et al., 1999, 2000]. In contrast to this general trend, volcanoes at Bioko Island and Mount Cameroon are solely made of basaltic lavas, and a few massifs such as Manengouba or Bamenda-Bambouto Mountains display a complete range from mafic to felsic rocks [Kagou Dongmo et al., 2001, Kamgang et al., 2007, 2008]. Mafic lavas composition comprises basanites, basalts, and hawaiites while felsic lavas include trachytes, rhyolites and/or phonolites in a given volcanic massif. According to the available geochronological data, the oldest volcanic activity in the CVL (73 to 40 Ma) corresponds to anorogenic complexes, while the youngest (0.48 ± 0.01 Ma to present) are well expressed in volcanic massifs along the ocean-continent boundary and in the oceanic sector [Marzoli et al., 2000, Kagou Dongmo et al., 2010]. The parental magmas generally display OIB features consistent with mantle plume activity, and originate from partial melting of various primitive mantle sources influenced by components such as HIMU or FOZO [Fitton, 1987, Halliday et al., 1990, Mbassa et al., 2012].

The CVL is marked by a NE–SW trending positive gravity anomaly in the continuity of the ”Poli–Ounianga–Kebir heavy line” extending from Cameroon to Chad [Figure 1B; Louis, 1970]. This gravity anomaly marks the northern border of the Adamawa plateau [Poudjom Djomani et al., 1992, PoudjomDjomani et al., 1997]. The crustal structure beneath the Cameroon Volcanic line is marked by a 10 km thick crust that contrasts with the 40 km thick crust along its edges [PoudjomDjomani et al., 1997, Tokam Kamga, 2010, Eloumala et al., 2014]. The mantle transitional zone beneath the CVL is approximately located at 250 ± 10 km [Reusch et al., 2010].

The West and Central African Rift System (WCARS), extending from the Hoggar to Cameroon and Chad, is defined as a complex set of interconnected pull-apart, wrench and extension basins [Fairhead et al., 2013], associated with two magmatic series, of Mesozoic and Cenozoic age, respectively [Ye et al., 2017]. It is further delineated by Meso-Cenozoic sedimentary deposits along the margins of intracratonic basins (southern Algeria, Murzug, Iullemmeden and Lake Chad basins), either on Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic sequences or directly on the Pan-African basement [Ye et al., 2017; Figure 1A,B].

In this paper, we present mineralogical and whole rock geochemical data of the unstudied Iriba basanites in order to constrain their petrogenesis and discuss their link with the CVL and the Central Africa Rift.

2. Geological context of the west and central Africa rift system

According to the detailed work of Genik [1993], Guiraud and Maurin [1992], Mchargue et al. [1992], Fairhead et al. [2013], the evolution of the WCARS can be summarized as tree stages: (1) Early Cretaceous opening of the rift marked by half basins in northern Nigeria and wester Sudan with an E–W extension direction and opening of the Benue trough in Cameroon and Sudan with a NE–SW direction of extension, (2) Mid-Cretaceous sag basin marked by deposition of sediments uncomfortably over the rift series, (3) Late Cretaceous to present-day rift inversion marked by upright folds, reverse and strike-slip faults and deposition of terrigenous sediments.

The Central Africa Rift System is parallel to the LVC in Cameroon and subdivides in (i) a northern branch delineated by the Lake Chad Basin and continuing towards the Tibesti massif, and (ii) an eastern branch delineated by sedimentary deposits south of the Guera massif and continuing towards the Iriba region in the Ouaddaï massif (Figure 1B).

2.1. Geological context of the central Africa rift system in chad

The geology of Chad consists of a Precambrian basement covered by Mesozoic to Cenozoic sedimentary sequences deposited in the Iullemmeden and Chad intracratonic basins and in the Benue and Léré rift basins that are also marked by the emplacement of volcanic rocks [Figure 1B; Bessoles and Trompette, 1980, Guiraud and Maurin, 1992, Milesi et al., 2010]. The volcanic rocks of Lake Chad (Hadjer Lamis), emplaced in the Cretaceous–Paleocene transition, are composed mainly of peralkaline rhyolites produced by fractional crystallization of parent magmas corresponding to alkaline basaltic melts, originating from a metasomatized mantle source [Mbowou et al., 2012, Shellnutt et al., 2016]. Based on geochronological and isotopic data, Shellnutt et al. [2016] suggest that silicic volcanic rocks from Lake Chad region are related to Late Cretaceous extensional volcanism in the Termit Basin. They conclude that magmatism was structurally controlled by Pan-African suture zones that were reactivated during the opening of the central Atlantic Ocean.

The Tibesti Volcanic Province (TVP; Figure 1B) represents the main volcanic activity in Chad. It is made of a variety of magmatic series including (i) Miocene Plateau volcanism consisting of flood basalts and silicic lava, with intercalated ignimbritic sheets emplaced from 17 to 8 Ma; (ii) basaltic cinder cones and associated lava flows emplaced from 7 to 5 Ma; (iii) Late Miocene large central composite volcanoes located along a major NNE–SSW trending fault; (iv) Large ignimbritic volcanoes (7–0.43 Ma); and (vi) the Tarso Toussidé Volcanic Complex. The volcanic rocks are localized along the southwestern NW–SE Tassilian flexure and an eastern NE–SW to NNE–SSW major fault zone [Deniel et al., 2015]. Geochemical data from Gourgaud and Vincent [2003] revealed the presence of alkaline volcanic rocks in Emi Koussi locality, forming a bimodal series made up of (1) a silica saturated suite, composed mainly of trachytes with a few trachyandesites and (2) a silica under-saturated suite, composed of basalts and phonolites. Overall, available geochemical and petrological data show that the volcanic activity is generally expressed by alkaline to peralkaline lavas ranging from basanites to arfvedsonite ± acmite-bearing rhyolites, all resulting from fractional crystallization of alkaline melts, probably originated from a metasomatized mantle source [Vicat et al., 2002, Gourgaud and Vincent, 2003].

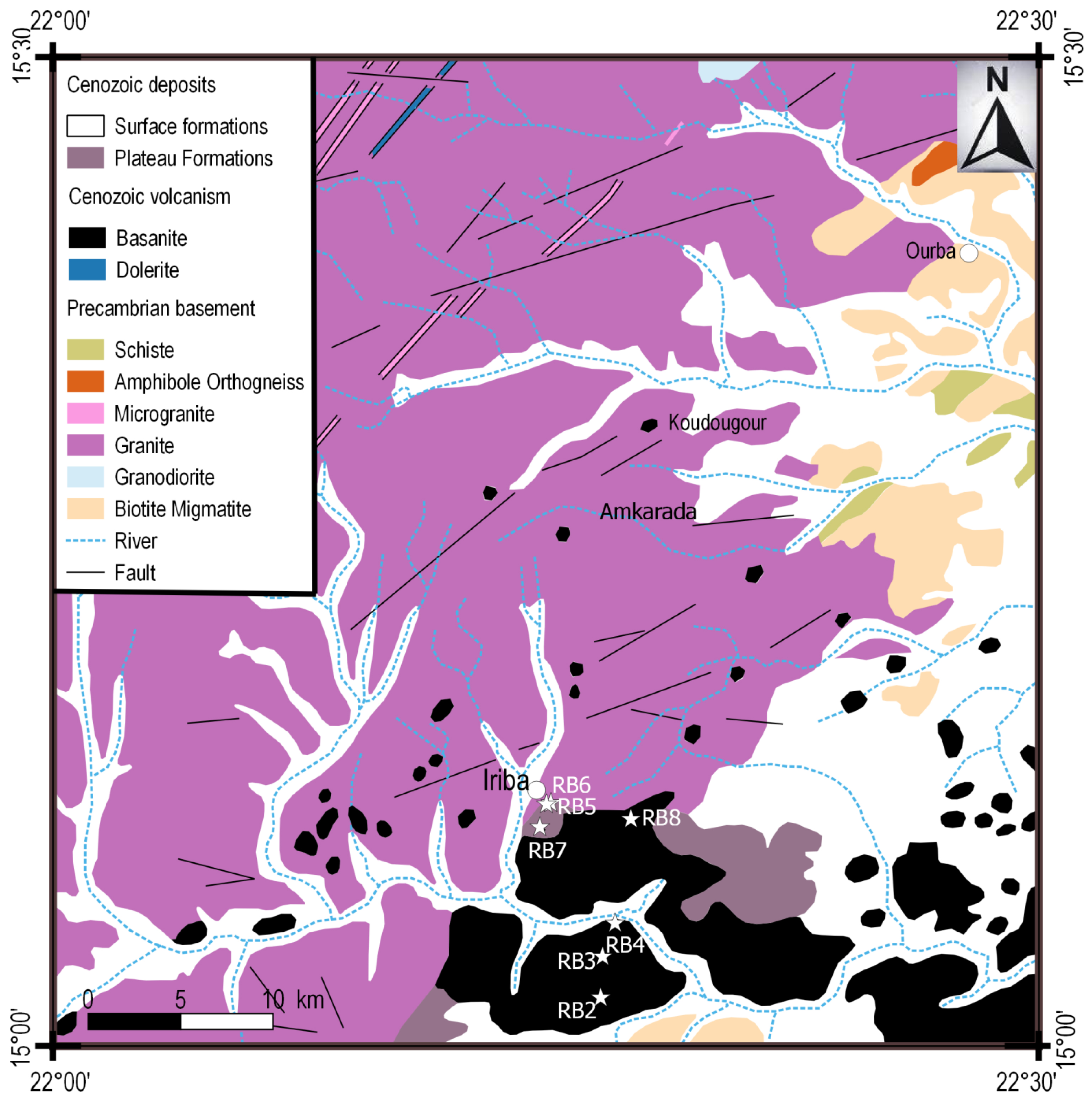

In the northern part of Ouaddaï massif, theralites and basalts are exposed [Gsell and Sonnet, 1962]. The Iriba basalts (Figure 2) outcrop in dome-shape or massive peak depressions from which emerge a series of superimposed flows of limited thickness (1 to 2 m), laying on plateau formations resulting from the weathering of basement rocks, or Paleozoic sandstones [Gsell and Sonnet, 1962]. Seven (7) samples have been selected for petrological and geochemical study.

Geological map of Iriba and the surrounding area, extracted from the geological reconnaissance map of the Equatorial African States, Niéré sheet N° ND 34 NE 0.80-E.81 [Gsell and Sonnet, 1962].

3. Analytical methods

Powders and thin sections of selected rock samples were prepared at the laboratory Geosciences Environment Toulouse, (GET-OMP-University of Toulouse 3, France) for geochemical and mineralogical analyses. Approximately 200 to 500 g of each sample was ground in a steel jaw crusher and then pulverized in an agate ball mill. The powders were then digested using an alkaline fusion procedure where the powder was mixed with lithium metaborate and melted to produce a glass pellet. The pellet was digested in dilute nitric acid prior to analysis. Analyses and digestions were carried out at the Service d’Analyse des Roches et des Minéraux (SARM, CRPG, France); major elements were determined by ICP-OES while trace elements were determined by ICP-MS following the procedure described in Carignan et al. [2001].

The major elements minerals compositions were performed at the Centre de microcaractérisation Raimond Castaing (Toulouse, France), using a CAMECA SX-Five Electron Probe Microanalyser. All analyzed samples were carbon coated (15 nm thick layer, density 2.25 g/cm3) before being introduced into the electron microprobe. The beam conditions were 15 kV accelerating voltage and 10 or 20 nA probe current. The synthetic and natural standards used for calibration were: albite (Na), corundum (Al), wollastonite (Si, Ca), sanidine (K), pyrophanite (Mn, Ti), hematite (Fe), periclase (Mg), Ni metal (Ni), Cr2O3 (Cr) and reference zircon (Zr). Element and background counting times for most analyzed elements were 10 s or 5 s (for Na and K), whereas, peak counting times were 120 s for Cr and 80 to 100 s for Ni and 240 s for Zr. Detection limits were 70 ppm for Cr and Zr and 100 ppm for Ni.

4. Petrography of the Iriba basanites

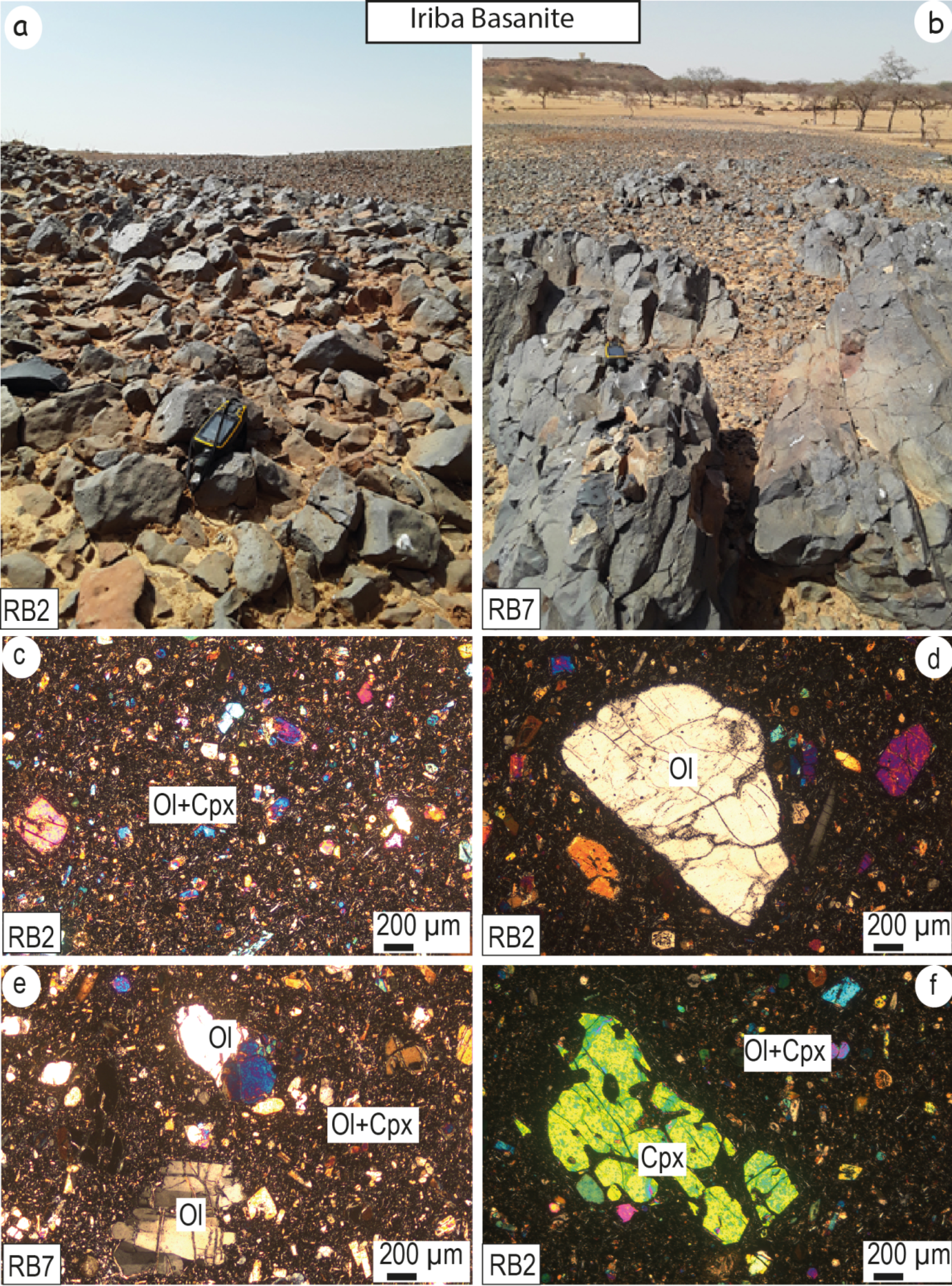

The Iriba basanites, are intrusive in the Paleozoic sandstones and are exposed as slabs or blocks within the plateau formations (Figure 3a,b). The Iriba basanites are characterized by a microlitic porphyritic texture (Figure 3c,d,f). Olivine, which constitutes 55 vol% of the rock, is present as sub-automorphic to xenomorphic phenocrysts and as microlites in the fine-grained groundmass. Olivine phenocrysts are fractured and altered into serpentine. Clinopyroxene represents 35 vol% of the rock and occurs as euhedral phenocrysts with clear cleavages and signs of corrosion. Plagioclase represents about 2–5 vol% and occurs as euhedral crystals with a dusty appearance due to the alteration. Opaque minerals (1–4 vol%) are sub-rounded or angular and generally included in olivine and clinopyroxene phenocrysts. Rare apatite (<2 vol%) is the only accessory mineral.

Different outcropping and representative photomicrographs of Iriba basanites. (a) Blocks; (b) slabs in the Paleozoic sandstone and plateau formations. (c) Porphyric texture of basanites; (d) and (e) Olivine phenocrysts and microlitic groundmass; (f) corroded and resorbed clinopyroxene phenocryst and microlitic groundmass.

5. Mineral chemistry

5.1. Olivine

Olivine phenocrysts are magnesian (Fo69.52–90.28 Fa09.72–39.48) with CaO ranging from 0.04 to 0.31 wt%. They are mostly chemically homogeneous but show slight chemical zoning with Fe enrichment from the core to the rim (Table 1). They are characterized by low MnO (0.05–0.31 wt%) and NiO (⩽0.45 wt%) contents.

Representative microprobe analyses of olivines from Iriba lavas

| Sample | RB8 | RB8 | RB8 | RB8 | RB8 | RB8 | RB8 | RB3 | RB3 | RB3 | RB3 | RB3 | RB3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C5 | C5 | C1 | C3 | C4 | C4 | C5 | C5 |

| Position | r | c | |||||||||||

| SiO2 | 39.71 | 40.24 | 40.01 | 39.69 | 40.33 | 39.80 | 38.72 | 40.17 | 40.32 | 38.90 | 39.37 | 40.97 | 39.59 |

| TiO2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Al2O3 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| FeO | 16.55 | 15.07 | 16.22 | 17.15 | 12.79 | 13.40 | 20.64 | 14.50 | 16.92 | 19.71 | 19.73 | 14.00 | 17.04 |

| MnO | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.31 |

| MgO | 44.27 | 44.96 | 44.02 | 43.37 | 46.97 | 46.30 | 40.59 | 45.79 | 43.91 | 41.77 | 41.68 | 45.83 | 43.71 |

| CaO | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.16 |

| Total | 101.04 | 100.67 | 100.70 | 100.54 | 100.43 | 99.72 | 100.74 | 101.01 | 101.48 | 100.87 | 101.17 | 101.27 | 100.85 |

| Si | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| Ti | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AlIV | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fe2+ | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.36 |

| Mn2+ | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Mg | 1.65 | 1.67 | 1.64 | 1.63 | 1.73 | 1.72 | 1.55 | 1.69 | 1.63 | 1.58 | 1.57 | 1.68 | 1.64 |

| Ca | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Total | 3.00 | 2.99 | 2.99 | 2.99 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.99 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.99 | 3.00 |

| Fa | 17.33 | 15.83 | 17.13 | 18.15 | 13.25 | 13.97 | 22.19 | 0.15 | 17.77 | 20.93 | 20.98 | 14.63 | 17.94 |

| Fo | 82.66 | 84.17 | 82.87 | 81.84 | 86.75 | 86.03 | 77.81 | 84.92 | 82.23 | 79.07 | 79.02 | 85.37 | 82.06 |

| Sample: | RB2 | RB2 | RB2 | RB2 | RB2 | RB7b | RB7b | RB7b | RB7b | RB7b | RB7b | RB7b | RB7b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | C4 | C4 | C3 | C3 | C2 | C2 | C1 | C1 | C1 | C2 | C2 | C2 | C3 |

| Position: | r | r | c | c | r | ||||||||

| SiO2 | 40.04 | 40.67 | 40.20 | 40.38 | 39.76 | 39.53 | 40.54 | 39.44 | 39.39 | 40.79 | 40.43 | 40.37 | 40.41 |

| TiO2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Al2O3 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| FeO | 12.33 | 12.38 | 15.49 | 15.79 | 18.77 | 15.13 | 14.46 | 19.59 | 19.64 | 14.71 | 14.24 | 14.93 | 14.25 |

| MnO | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.19 |

| MgO | 47.97 | 47.95 | 44.68 | 44.65 | 42.25 | 45.51 | 46.02 | 42.15 | 41.98 | 45.94 | 46.35 | 45.57 | 46.63 |

| CaO | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| Total | 100.74 | 101.31 | 100.94 | 101.30 | 101.39 | 100.71 | 101.56 | 101.55 | 101.45 | 101.93 | 101.61 | 101.48 | 101.81 |

| Si | 0.98 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| Ti | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AlIV | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fe2+ | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.29 |

| Mn2+ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mg | 1.76 | 1.75 | 1.66 | 1.65 | 1.58 | 1.69 | 1.69 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 1.68 | 1.70 | 1.68 | 1.71 |

| Ca | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Total | 3.01 | 3.00 | 2.99 | 2.99 | 2.99 | 3.01 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.99 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Fa | 12.60 | 12.65 | 16.28 | 16.55 | 19.95 | 15.72 | 14.98 | 20.68 | 20.79 | 15.23 | 14.70 | 15.52 | 0.1463 |

| Fo | 87.40 | 87.35 | 83.72 | 83.45 | 80.05 | 84.28 | 85.01 | 79.32 | 79.21 | 84.77 | 85.30 | 84.47 | 85.37 |

| Sample: | RB7b | RB7b | RB7b | RB7a | RB7a | RB7a | RB7a | RB7a | RB7a | RB7a | RB7a | RB7a | RB7a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | C3 | C4 | C4 | C5 | C5 | C4 | C4 | C4 | C3 | C3 | C1 | C1 | C1 |

| Position: | r | r | c | r | c | r | c | m | r | c | r | c | r |

| SiO2 | 38.91 | 39.99 | 40.01 | 41.16 | 40.95 | 41.17 | 41.28 | 39.77 | 41.80 | 41.47 | 39.57 | 39.24 | 39.64 |

| TiO2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Al2O3 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| FeO | 21.59 | 14.64 | 14.71 | 9.56 | 12.29 | 12.97 | 12.28 | 15.93 | 9.80 | 9.75 | 20.15 | 18.43 | 19.67 |

| MnO | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| MgO | 40.65 | 46.61 | 45.88 | 49.84 | 47.67 | 46.57 | 47.46 | 44.29 | 49.23 | 49.35 | 41.42 | 42.89 | 42.06 |

| CaO | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| Total | 101.62 | 101.65 | 100.92 | 100.78 | 101.37 | 101.12 | 101.44 | 100.63 | 101.10 | 100.84 | 101.70 | 101.19 | 101.94 |

| Si | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| Ti | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| AlIV | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fe2+ | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.41 |

| Mn2+ | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Mg | 1.54 | 1.71 | 1.70 | 1.80 | 1.73 | 1.70 | 1.72 | 1.65 | 1.77 | 1.78 | 1.56 | 1.61 | 1.58 |

| Ca | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Total | 3.01 | 3.01 | 3.00 | 2.99 | 2.99 | 2.98 | 2.98 | 3.00 | 2.98 | 2.99 | 3.00 | 3.01 | 3.00 |

| Fa | 22.95 | 14.98 | 15.24 | 9.71 | 12.63 | 13.51 | 12.67 | 16.79 | 10.04 | 9.98 | 21.44 | 19.42 | 20.78 |

| Fo | 77.04 | 85.02 | 84.76 | 90.28 | 87.36 | 86.49 | 87.32 | 83.21 | 89.95 | 90.02 | 78.56 | 80.58 | 79.22 |

C = core; r = rim; m = microlite; FeO = FeO total.

5.2. Clinopyroxene

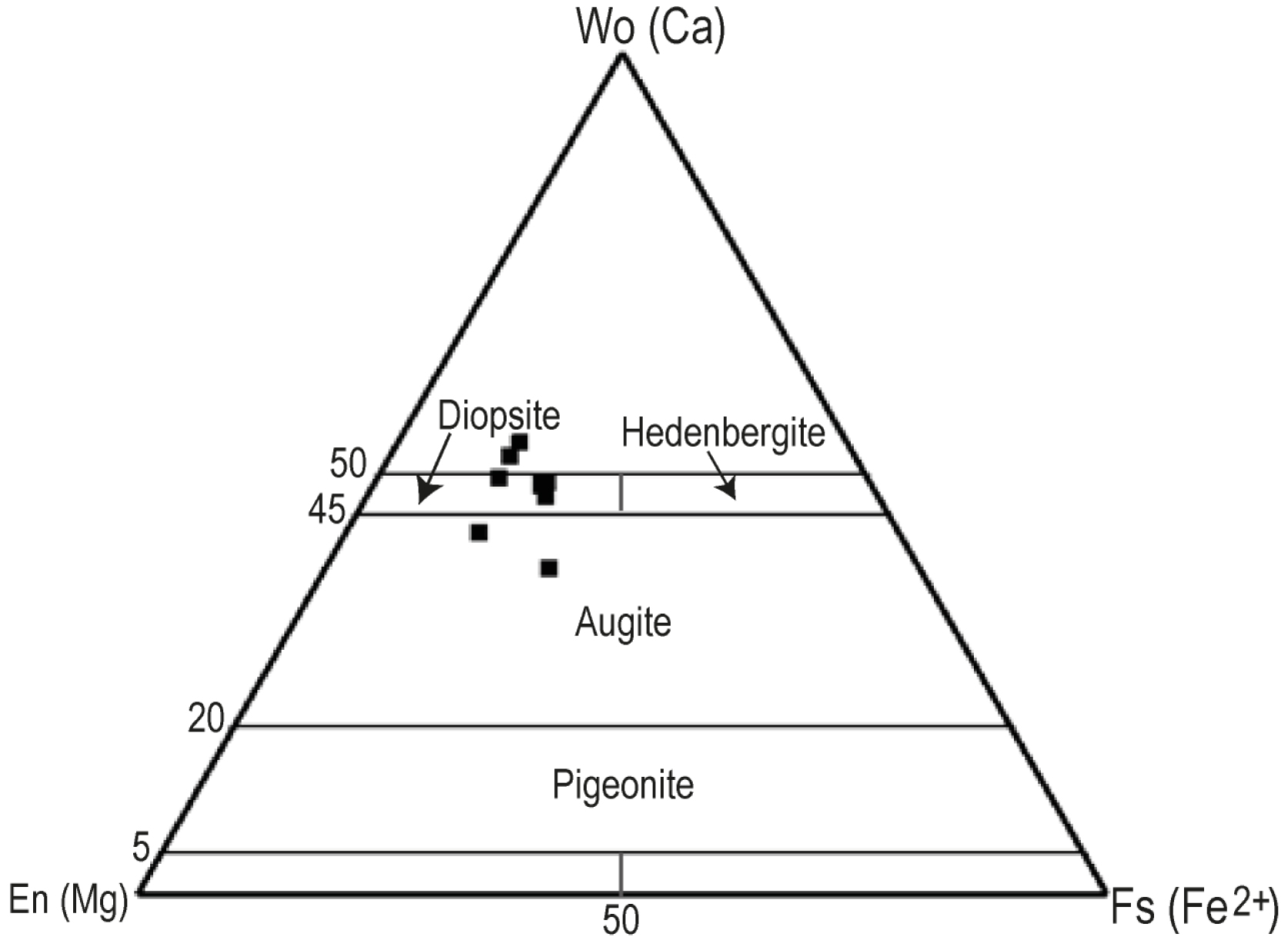

The selected pyroxenes analyses are reported in Table 2. Clinopyroxenes (Cpx) are Ca- and Mg- rich (Wo38.8–53.7–En33.4–43.2) with variable Fe composition (Fs12.4–23). According to the classification of Morimoto et al. [1988], the Cpx of Iriba basanites have a composition of diopside (Wo47.22–49.41En33.37–38.01Fs12.36–17.76) and augite (Wo38.75–43.07En38.23–43.22Fs13.71–23.02) (Figure 4). Some clinopyroxene crystals display Wo contents > 50%. Similar Cpx with Wo > 50% are commonly found in CVL such as basanites from Bamenda Mountains [Kamgang et al., 2008], Mbengwi [Mbassa et al., 2012] and Mount Bambouto [Wandji et al., 2000]. The phenocrysts are variably rich in Al2O3 (2.96–9.94 wt%) and TiO2 (0.4–4.49 wt%) with the highest contents of both Al and Ti in the crystals rims. Their Mg#vary from 66 to 88.

Ca-pyroxenes of Iriba basanites in Wo-En-Fs ternary diagram of Morimoto et al. [1988]. Wo = Wollastonite; En = Enstatite; Fs = ferrosilite.

Representative microprobe analyses of clinopyroxenes from Iriba lavas

| Sample | RB3 | RB2 | RB2 | RB2 | RB2 | RB2 | RB2 | RB7a | RB7a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | C2 | C3 | C2 | C2 | C2 | C2 | C1 | C2 | C1 |

| Positions | c | b | b | ||||||

| SiO2 | 51.19 | 48.16 | 50.75 | 49.95 | 49.90 | 50.31 | 50.08 | 45.67 | 43.29 |

| TiO2 | 1.17 | 2.08 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 3.31 | 4.49 |

| Al2O3 | 2.96 | 6.89 | 3.91 | 5.19 | 4.94 | 4.88 | 4.88 | 8.13 | 9.94 |

| FeO | 8.40 | 7.29 | 13.44 | 10.48 | 10.85 | 10.08 | 10.17 | 7.26 | 7.31 |

| MnO | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

| MgO | 15.16 | 12.65 | 12.92 | 11.28 | 11.62 | 11.42 | 11.51 | 11.97 | 11.05 |

| CaO | 21.02 | 22.88 | 18.22 | 22.98 | 22.21 | 22.82 | 22.77 | 24.32 | 24.44 |

| Na2O | 0.56 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.36 | 0.45 |

| Total | 100.63 | 100.86 | 100.68 | 101.62 | 101.21 | 101.11 | 101.10 | 101.16 | 101.00 |

| Si | 1.89 | 1.78 | 1.90 | 1.86 | 1.86 | 1.87 | 1.87 | 1.70 | 1.62 |

| Ti | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| AlIV | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.38 |

| AlVI | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Fe3+ | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| Fe2+ | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Mn2+ | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mg | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.62 |

| Ca | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Na | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Total | 4.03 | 4.03 | 4.01 | 4.03 | 4.03 | 4.02 | 4.03 | 4.04 | 4.04 |

| Wo | 43.07 | 49.41 | 38.75 | 48.86 | 47.22 | 48.81 | 48.55 | 52.02 | 53.66 |

| En | 43.22 | 38.01 | 38.23 | 33.37 | 34.37 | 33.99 | 34.14 | 35.62 | 33.76 |

| Fs | 13.71 | 12.58 | 23.02 | 17.76 | 18.41 | 17.20 | 17.31 | 12.36 | 12.58 |

C = core; b = rim; FeO = FeO total.

5.3. Feldspars

Feldspar crystals are scarce in the studied basanites and correspond to Na-rich plagioclase (An2.09Ab80.10Or17.80) (Table 3).

Representative microprobe analyses of feldspars and opaque minerals from Iriba lavas

| Feldspars | Opaque minerals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | RB2-C3 | Sample | RB3 | RB2 | RB7a | |

| Analysis | C3 | Analysis | C5 | C2 | C3 | |

| Position | r | Position | ||||

| SiO2 | 68.55 | SiO2 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.14 | |

| Al2O3 | 19.71 | TiO2 | 15.81 | 0.05 | 0.97 | |

| FeO | 0.15 | Al2O3 | 1.63 | 0.02 | 46.49 | |

| CaO | 0.46 | FeO | 71.32 | 78.18 | 20.30 | |

| Na2O | 9.74 | Fe2O3 | 7.93 | 8.69 | 2.26 | |

| K2O | 3.29 | Cr2O3 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 12.24 | |

| Total | 101.90 | MnO | 0.59 | 0.14 | 0.18 | |

| Si | 11.91 | MgO | 1.50 | 0.00 | 17.29 | |

| Al | 4.04 | NiO | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.25 | |

| Fe total | 0.02 | Total | 99.88 | 87.59 | 100.12 | |

| Ca | 0.09 | Ti | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| Na | 3.28 | Al | 0.06 | 0.00 | 1.16 | |

| K | 0.73 | Fe2+ | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Total | 20.07 | Fe3+ | 1.64 | 1.96 | 0.36 | |

| Or | 17.80 | Mg | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.54 | |

| Ab | 80.10 | Total | 2.48 | 1.96 | 2.08 | |

| An | 2.09 | xMg | 3.58 | 0.00 | 60.08 | |

| xFe | 95.61 | 99.82 | 39.57 | |||

| xMn | 0.80 | 0.18 | 0.35 | |||

r = rim.

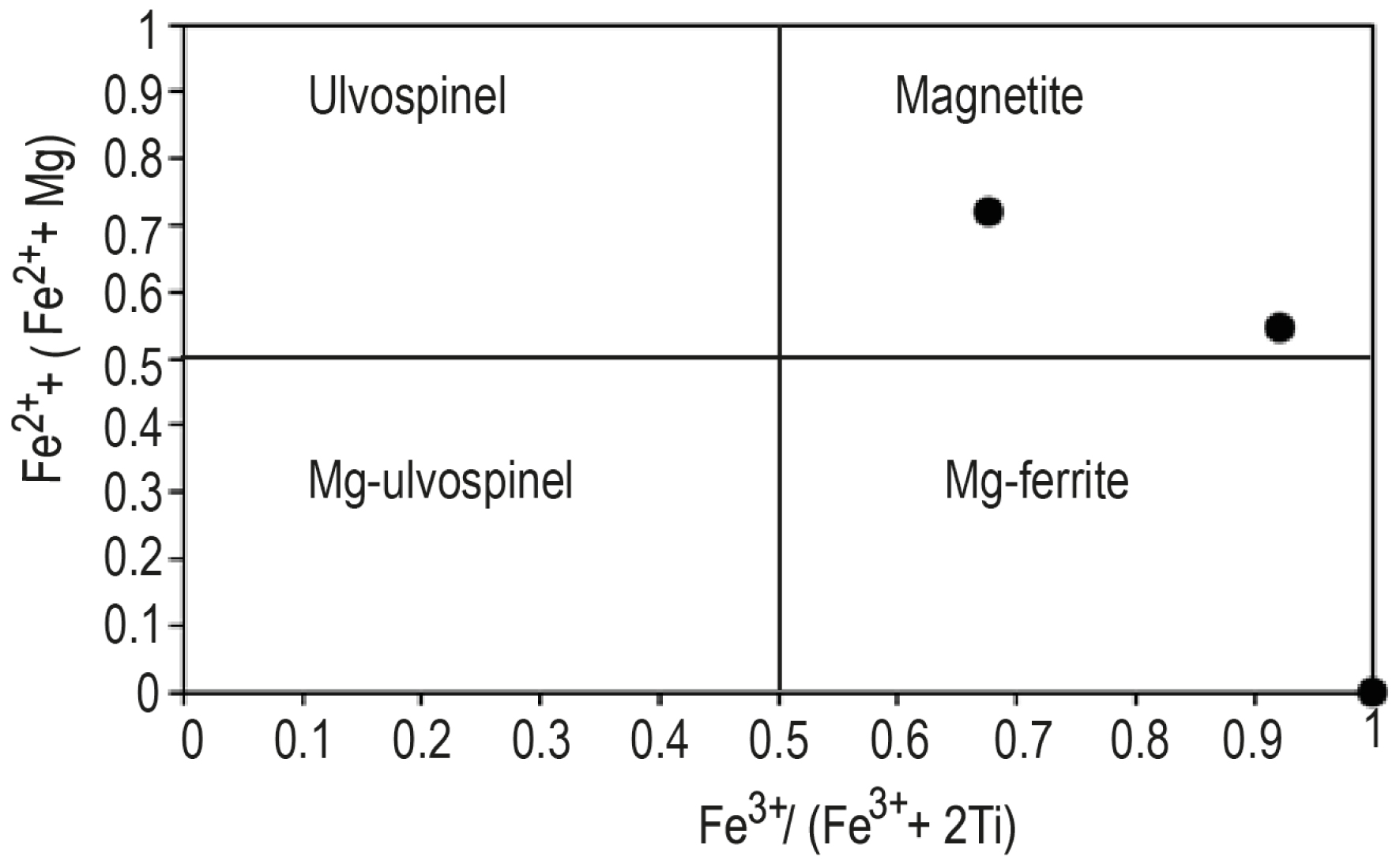

5.4. Opaque minerals

Opaque minerals (Table 3) are spinels (Mg3.58–60.08Fe39–99Mn0.18–0.80). They correspond to ulvospinel, magnetite and magnesioferrite according to the classification of Haggerty and Tompkins [1984] (Figure 5). The samples RB2 and RB7a are characterized by TiO2 contents >0.20 wt% (0.95–15.81 wt%) with Fe2+/Fe3+ ratios <2. These characteristics are indicative of their non-mantelic origin according to Kamenetsky et al. [2001]. They are also characterised by Cr#(100Cr/(Cr+Al)) ranging between 11.24 and 25.12 and are fairly NiO-rich (0.25–0.50 wt%) except RB3 which is NiO-poor (0.01 wt%).

Composition of opaque minerals after Haggerty and Tompkins [1984].

6. Whole rock geochemistry

6.1. Major elements

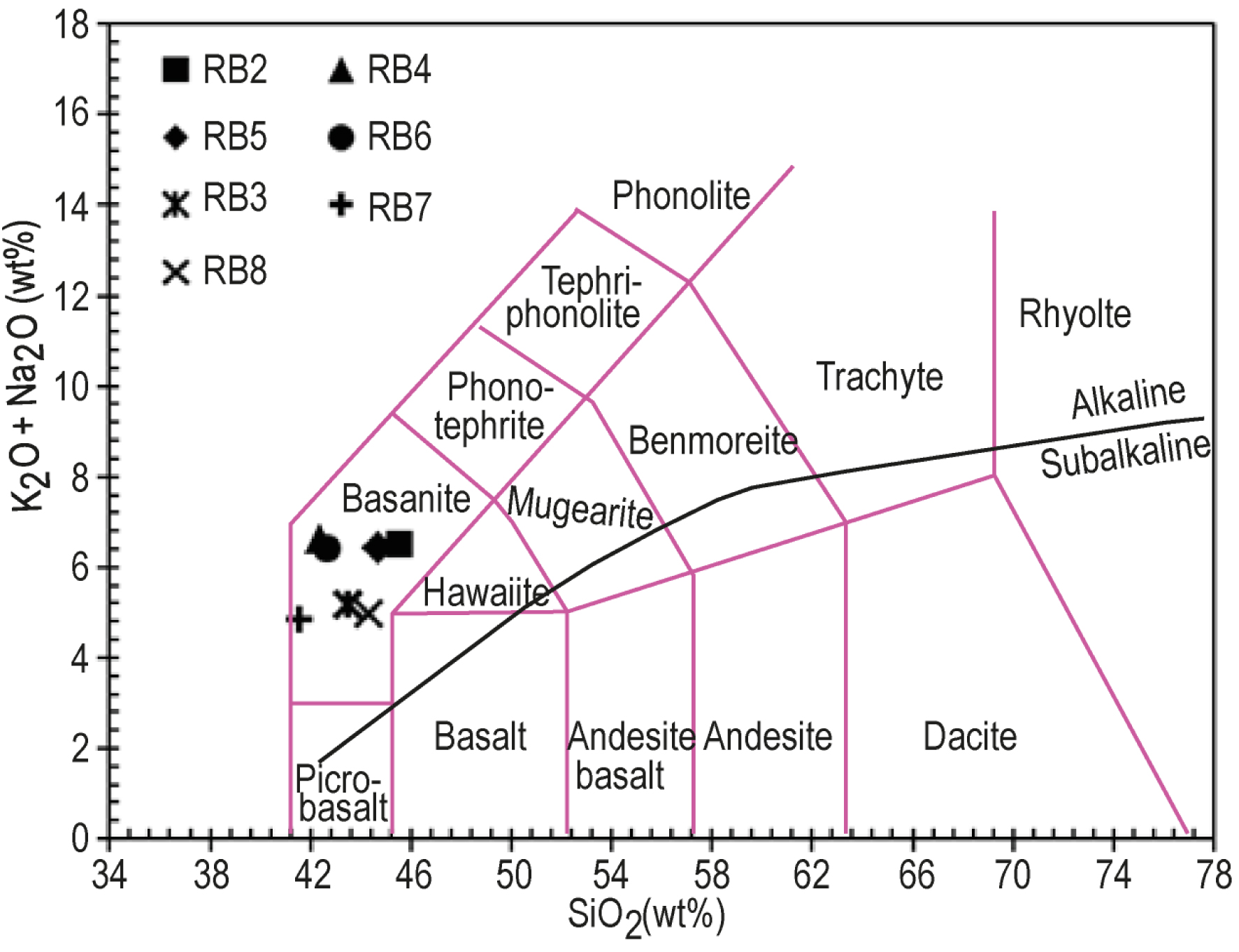

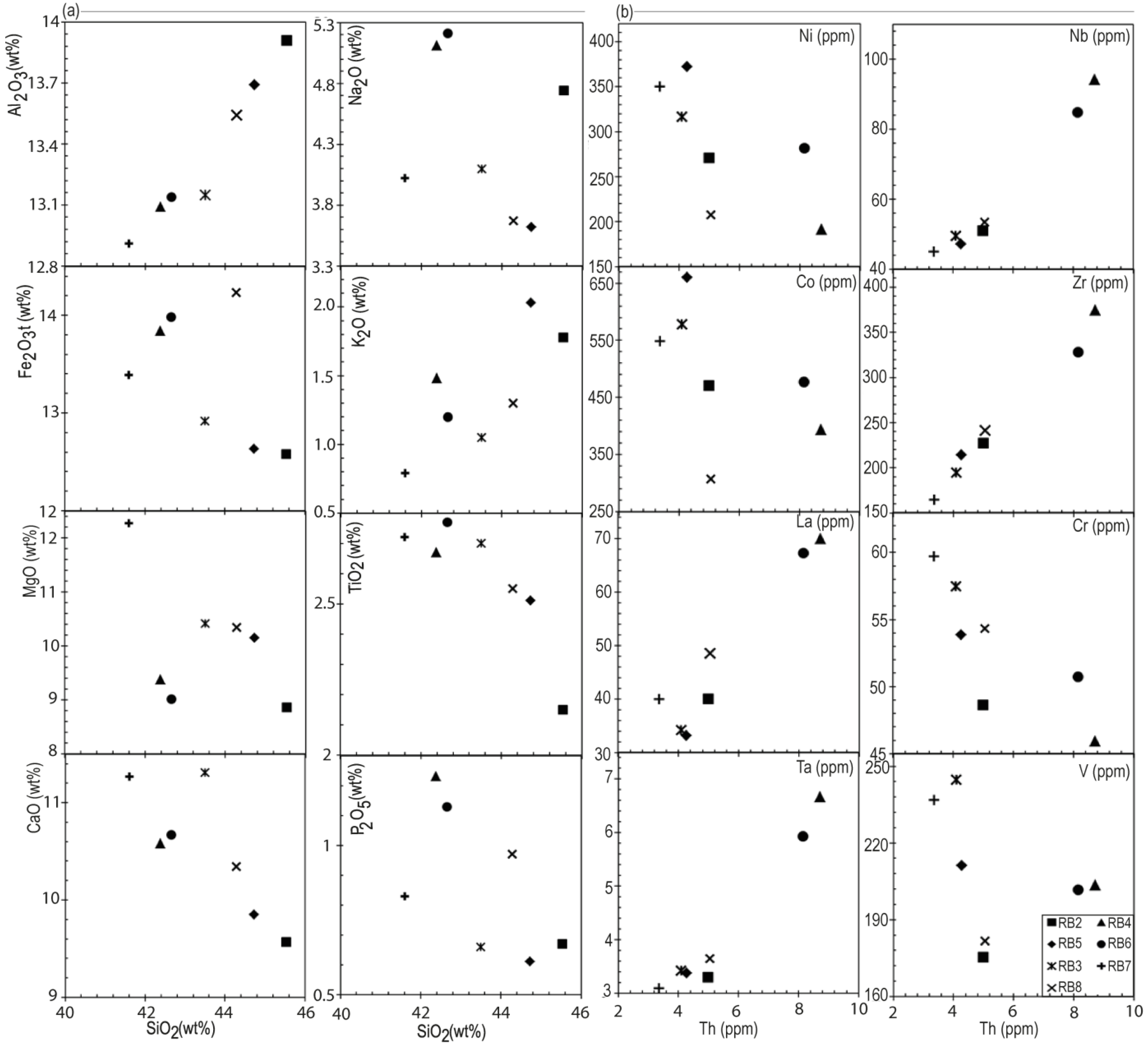

Chemical analyses (major and trace elements) of Iriba lavas are reported in Table 4. SiO2 contents range from 41 to 46 wt% and TiO2 contents from 2.15 to 2.77 wt%, with high K2O+Na2O (4.97–6.59 wt%) and MgO contents expressed by Mg#(100 Mg/[Mg + Fe]) ranging between 56 and 65. According to the TAS diagram [after Le Bas et al., 1986; Figure 6], they are classify as basanites. All the samples are alkaline with a sodic tendency according to criteria defined by Irvine and Baragar [1971] and Middlemost [1975]. In the major elements Harker diagrams (Figure 7a), Al2O3 and K2O contents are positively correlated with SiO2 while MgO, TiO2, CaO and P2O5 display a negative correlation.

Whole rock composition of Iriba basanites

| Sample | RB2 | RB3 | RB4 | RB5 | RB6 | RB7 | RB8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 45.53 | 43.50 | 42.38 | 44.73 | 42.66 | 41.60 | 44.29 |

| Al2O3 | 13.91 | 13.15 | 13.09 | 13.69 | 13.14 | 12.91 | 13.54 |

| Fe2O3t | 12.58 | 12.92 | 13.84 | 12.63 | 13.98 | 13.39 | 14.23 |

| MnO | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| MgO | 8.86 | 10.41 | 9.38 | 10.15 | 9.01 | 12.27 | 8.92 |

| CaO | 9.57 | 11.31 | 10.58 | 9.85 | 10.67 | 11.27 | 10.34 |

| Na2O | 4.74 | 4.10 | 5.11 | 3.62 | 5.21 | 4.02 | 3.67 |

| K2O | 1.78 | 1.05 | 1.48 | 2.03 | 1.20 | 0.79 | 1.30 |

| TiO2 | 2.15 | 2.70 | 2.67 | 2.51 | 2.77 | 2.72 | 2.55 |

| P2O5 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 1.23 | 0.61 | 1.13 | 0.83 | 0.97 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.01 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.99 | 100.01 |

| Mg# | 58.42 | 61.65 | 57.46 | 61.57 | 56.22 | 64.63 | 55.56 |

| ppm | |||||||

| Rb | 36.92 | 25.88 | 24.18 | 42.39 | 67.47 | 50.01 | 50.87 |

| Sr | 969.28 | 742.93 | 1214.25 | 829.19 | 1189.9 | 887.15 | 985.83 |

| Ba | 592.63 | 476.46 | 665.51 | 446.71 | 627.85 | 597.08 | 510.53 |

| V | 175.43 | 244.85 | 203.58 | 211.12 | 201.81 | 236.67 | 181.67 |

| Cu | 58.23 | 60.31 | 45.12 | 57.50 | 45.22 | 56.24 | 53.44 |

| Cr | 48.63 | 57.48 | 45.92 | 53.86 | 50.72 | 59.68 | 54.30 |

| Co | 470.93 | 578.19 | 393.64 | 659.70 | 477.27 | 548.05 | 306.75 |

| Ni | 271.06 | 316.59 | 191.63 | 372.14 | 281.87 | 349.86 | 207.41 |

| Sc | 18.63 | 23.76 | 19.29 | 22.17 | 18.81 | 23.74 | 16.58 |

| Zn | 122.23 | 105.36 | 130.63 | 105.44 | 189.20 | 104.97 | 148.10 |

| Y | 25.41 | 20.28 | 31.83 | 21.46 | 30.58 | 25.42 | 22.96 |

| Zr | 227.56 | 194.78 | 374.16 | 214.35 | 328.14 | 164.37 | 241.31 |

| Hf | 4.72 | 4.37 | 7.52 | 4.65 | 6.73 | 3.95 | 5.19 |

| Ta | 3.30 | 3.42 | 6.66 | 3.37 | 5.93 | 3.09 | 3.64 |

| Nb | 50.96 | 49.53 | 94.20 | 47.24 | 84.81 | 44.96 | 53.44 |

| La | 40.07 | 34.26 | 69.95 | 33.21 | 67.28 | 39.93 | 48.51 |

| Ce | 79.29 | 67.99 | 134.75 | 66.12 | 130.58 | 81.20 | 96.50 |

| Pr | 9.19 | 8.01 | 15.29 | 7.79 | 14.85 | 9.71 | 11.15 |

| Nd | 36.30 | 32.07 | 58.65 | 31.32 | 57.17 | 39.25 | 44.43 |

| Sm | 7.59 | 6.73 | 11.15 | 6.62 | 11.05 | 8.33 | 9.15 |

| Eu | 2.50 | 2.16 | 3.46 | 2.15 | 3.45 | 2.68 | 2.92 |

| Gd | 6.61 | 5.65 | 9.03 | 5.76 | 9.05 | 7.11 | 7.57 |

| Tb | 0.98 | 0.81 | 1.26 | 0.83 | 1.25 | 1.01 | 1.04 |

| Dy | 5.44 | 4.44 | 6.84 | 4.57 | 6.76 | 5.56 | 5.36 |

| Ho | 1.01 | 0.81 | 1.26 | 0.85 | 1.22 | 1.02 | 0.92 |

| Er | 2.47 | 1.90 | 2.99 | 2.04 | 2.84 | 2.40 | 2.04 |

| Tm | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.25 |

| Yb | 2.00 | 1.47 | 2.42 | 1.61 | 2.17 | 1.83 | 1.40 |

| Lu | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.18 |

| Th | 4.98 | 4.09 | 8.73 | 4.27 | 8.15 | 3.36 | 5.06 |

| U | 1.32 | 1.17 | 2.71 | 1.21 | 2.28 | 0.95 | 1.36 |

Total alkali-silica diagram [after Le Bas et al., 1986]. The dark line separates the alkaline and the subalkaline domain, according to Irvine and Baragar [1971].

(a) Major elements (wt%) versus SiO2 distribution; (b) Trace elements distribution (Th versus Ni, Nb, Co, Zr, La, Cr, Ta and V) of the Iriba basanites.

6.2. Trace elements

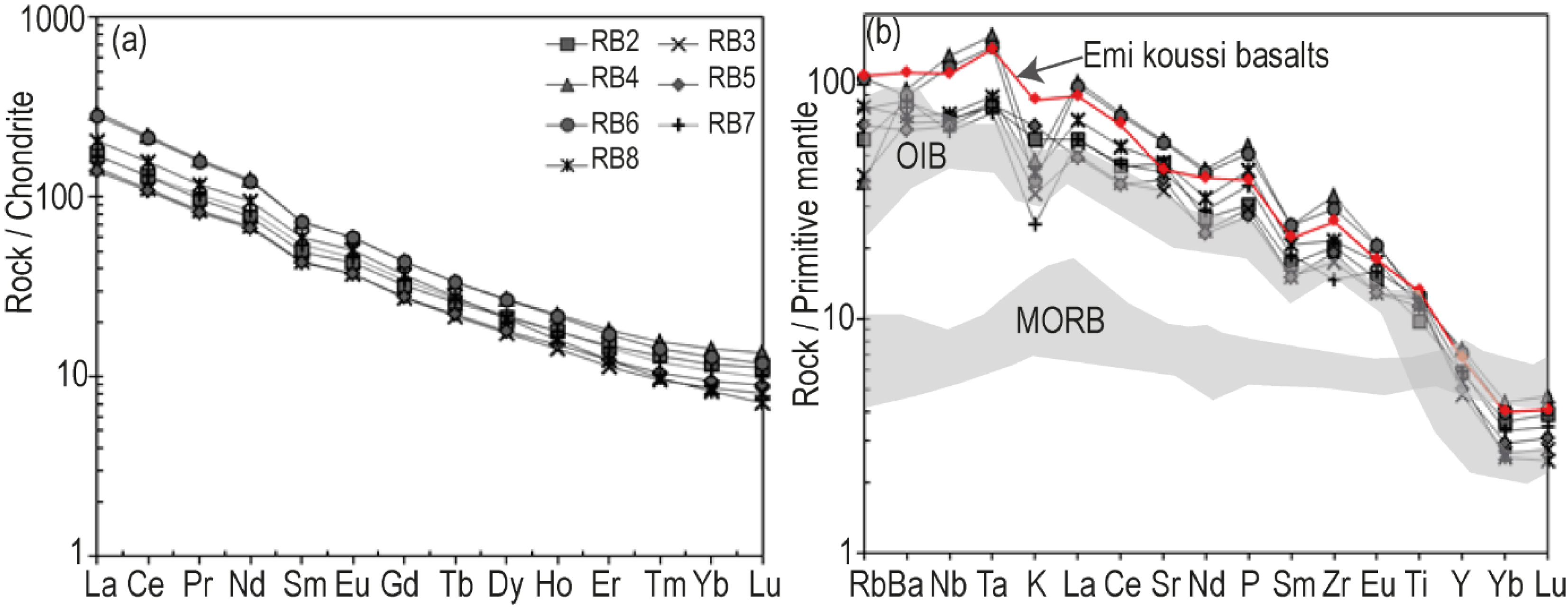

Compatible or slightly incompatible trace elements concentrations are variable: Sc (17–24 ppm), V (175–245 ppm), Cr (46–60 ppm), Co (307–660 ppm), Ni (192–372 ppm), Cu (45–60 ppm) and Zn (105–189 ppm) (Table 4). In the trace elements x–y diagrams (Figure 7b), highly incompatible elements such as Nb, Zr, La and Ta show positive trends with each other, while compatible trace elements such as Ni, Cr, Co and V show negative trends. REE element contents (Figure 8a) show enrichment in LREE (14.37 ⩽ (La/Yd)N⩽24.82) compared to MREE and HREE (2.73⩽ (Gd/Yb)N⩽4.46).

(a) Chondrite normalized REE paterns and (b) primitive mantle normalized trace elements diagrams of Iriba basanites. The normalization values are after Sun and Mcdonough [1989].

7. Discussion

7.1. Magmatic differentiation of the Iriba basanites

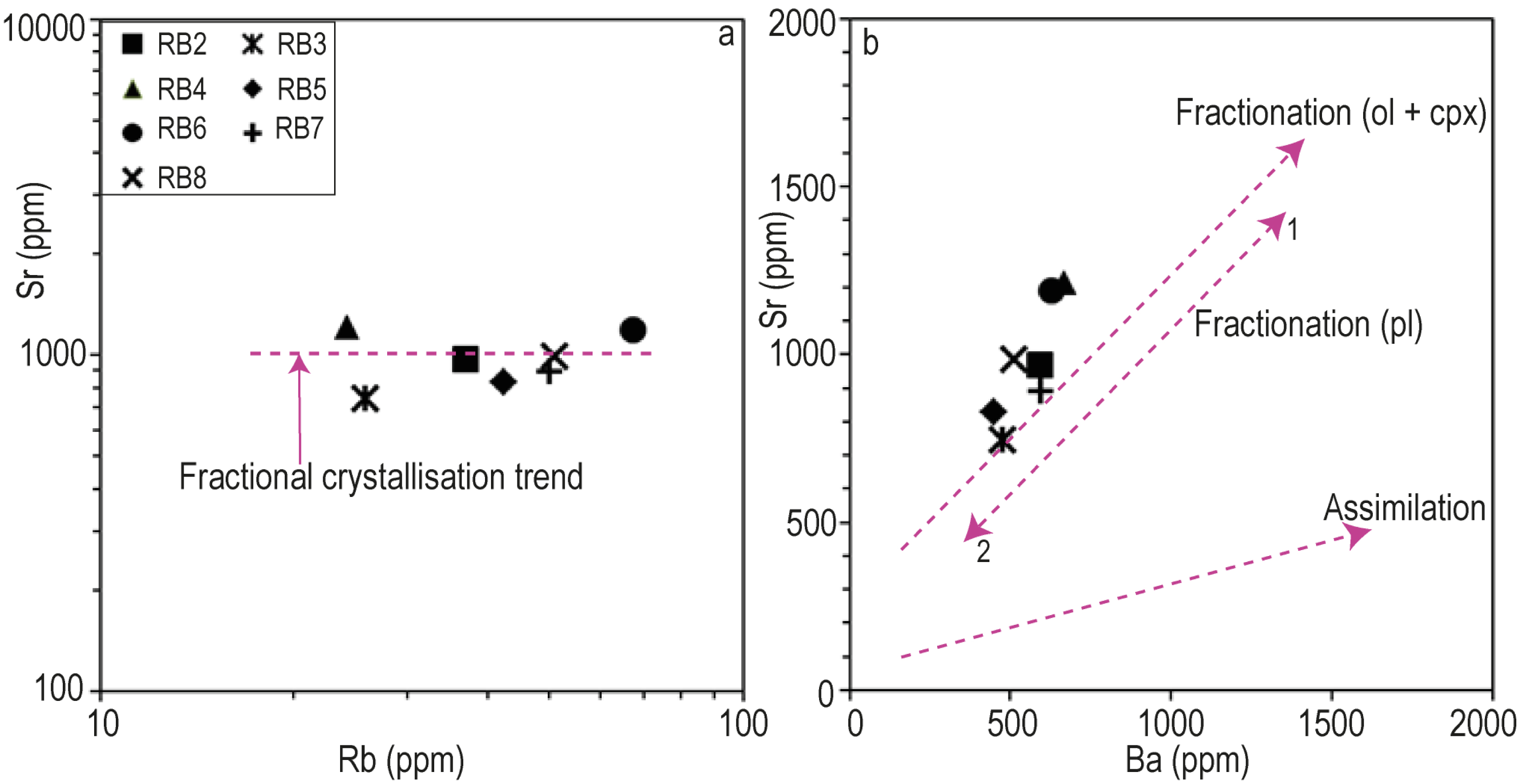

Given their low silica contents, their high Ni (207–372 ppm) and Cr (45–597 ppm) contents most of the Iriba basanites, might be considered as crystallized from a primary magma as defined by Frey et al. [1978], eventhough they display a MgO content (8.6–12 wt%; Mg#⩽65) slightly below the one of the primary magmas. These characteristics may be consistent with an evolution through fractional crystallization with or without crustal contamination. The relative contributions of these processes can be deciphered from the analysis of major and trace elements compositions. The negative correlations of CaO concentration with SiO2 and of Ni, Cr, Co and V with Th (Figure 8a,b), suggest fractionation linked to the crystallization of olivine, clinopyroxene, oxides and feldspar. Olivine and clinopyroxene fractionation are further suggested by the linear trend in the Sr versus Ba diagram [Franz et al., 1999, Figure 9b]. The positive correlations of Al2O3 with SiO2 and that of Zr with Th likely imply a fractionation of plagioclase and zircon respectively. Fractional crystallization is also consistent with (i) the enrichment in LREE, (ii) the similarity of hygromagmatophilic elements ratios such as Zr/Nb, Th/Hf and La/Ta, (iii) the parallelism of the REE patterns (Figure 8a,b), and (iv) the horizontal trend of the studied basanites in the Sr versus Rb diagram of Xu et al, 2007 (Figure 9a). Nevertheless, the relatively high Ni (192–350 ppm) and Co (307–660 ppm) contents of the basanites points to a low degree of fractional crystallization of the parental magma.

(a) Illustration of fractional crystallization trend in Rb versus Sr diagram [Xu et al., 2007] and (b) illustration of olivine and clinopyroxene fractionation in the Sr versus Ba diagram of Franz et al. [1999].

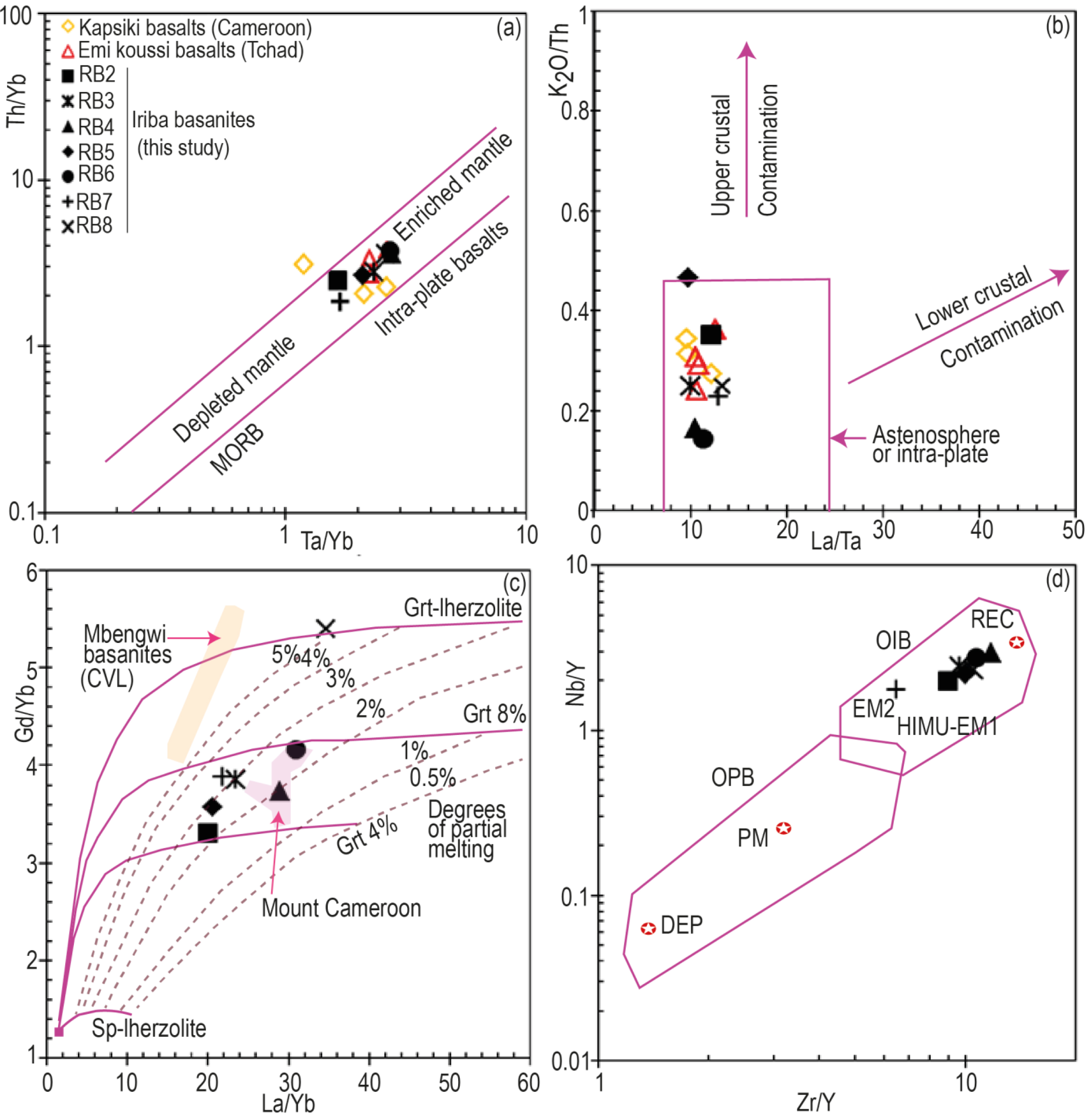

The range of P2O5 contents of the studied basanites (0.6 < P2O5 < 1.9) points to a complete lack of crustal contamination. This is confirmed in the K2O/Th versus La/Ta diagram (Figure 10a,b), where the Iriba lavas fall within the field of uncontaminated basalts. Such features are similar to that of some lavas from northern Cameroon, notably the Ngaoundéré basaltic lavas [0.9 < P2O5 < 1.3; Nkouandou et al., 2010]; [0.4 < P2O5 < 1.4; Fitton, 1987] and the Kapsiki basalts [0.6 < P2O5 < 1.2; Ngounouno et al., 2000].

Position of the studied basanites in (a) Th/Yb versus Ta/Yb [from Pearce, 1982, 1983] and (b) K2O/Th versus La/Ta diagrams. (c) Gd/Yb versus La/Yb diagram [after Yokoyama et al., 2007] illustrating the partial melting of Iriba basanites. The curves at Grt 4% and 8% correspond to the garnet content in the source [Halliday et al., 1995]. CVL = Cameroon Volcanic Line. (d) Nb/Y versus Zr/Y diagram of Weaver [1991] and Condie [2005]. OIB = Ocean Island Basalts, OPB = Ocean Plateau Basalts, PM = primitive mantle, DEP = highly depleted mantle, REC = recycled component; HIMU = high 238U/204Pb mantle source, EM1 and EM2 enriched mantle sources. Masquer

Position of the studied basanites in (a) Th/Yb versus Ta/Yb [from Pearce, 1982, 1983] and (b) K2O/Th versus La/Ta diagrams. (c) Gd/Yb versus La/Yb diagram [after Yokoyama et al., 2007] illustrating the partial melting of Iriba basanites. The curves ... Lire la suite

7.2. Source of the Iriba basanites and conditions of partial melting

The Iriba basanites display characteristics of intraplate magmas (Figure 10a,b), generated by partial melting of an enriched mantle source. A similar intraplate signature is displayed by alkaline continental basalts exposed in Emi-Koussi in Chad [Gourgaud and Vincent, 2003] and by alkaline basalts from Mayo Oulo-Léré, Babouri-Figuil, located at the Cameroon-Chad border Ngounouno et al. [2000]. The geochemical signatures of the Iriba basanites point to a higher degree of partial melting (2–4%) than the ones from Baossi-Warack [0.5–2%; Tiabou et al., 2018] and from Mt Cameroon [1–2%; Yokoyama et al., 2007] but lower than that of basanites from Mbengwi [5–8%; Mbassa et al., 2012].

Assuming that MREE/HREE ratios are sensitive to the amount of residual garnet in the source, the range of the studied Iriba basanites (Tb/Yb)N ratios (2.22–3.37) is higher than 1.7 and is consistent with the presence of garnet in the source, as proposed by Wang et al. [2002]. This interpretation is corroborated by the position of the Iriba basanites in the Gd/Yb versus La/Yb diagram (Figure 10c), which indicates partial melting of a lherzolitic mantle containing less than 8% of garnet, except for sample RB8, characterized by high levels of Gd and La but low levels of Yb. The ranges of some incompatible trace elements ratios such as Zr/Nb, La/Nb, Ba/Nb, Rb/Nb and Ba/La of Iriba basanites (Table 5) are typical of Ocean Island Basalts (OIB) defined by Zindler and Hart [1986]. This OIB affinity is also confirmed in the Nb/Y versus Zr/Y diagram of Weaver [1991], with an imposing role for recycled components and the HIMU-EM1 mantle poles, except one sample plotting close to the enriched EM2 pole (Figure 10d).

Comparative incompatible elements contents of Iriba alkaline basanites with those of the crust and certain mantle reservoirs [Zindler and Hart, 1986]

| Zr/Nb | La/Nb | Ba/Nb | Rb/Nb | Ba/La | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iriba basanites | 3.6–4.5 | 0.69–0.90 | 7.0–13.2 | 0.25–1.11 | 9.33–14.95 |

| Continental crust | 16.2 | 2.2 | 54 | 4.7 | 25 |

| Primitive mantle | 14.8 | 0.94 | 9 | 0.91 | 9.6 |

| N-MORB | 46.2 | 1.07 | 1.7–8.0 | 0.36 | 4 |

| E-MORB | 14.07 | 1.05 | 4.9–8.5 | nd | nd |

| HIMU–OIB | 3.2–5.6 | 0.66–0.77 | 4.9–6.9 | 0.35–0.38 | 6.8–8.7 |

| EM1–OIB | 4.2–11.5 | 0.86–1.19 | 11.4–17.8 | 0.88–1.77 | 13.2–16.9 |

| EM2–OIB | 4.5–7.3 | 0.89–1.11 | 7.3–13.3 | 0.59–0.85 | 8.3–11.3 |

7.3. The Cameroon chad volcanic line

The Iriba basanites are similar to alkaline magmatic series emplaced along the Central Africa Rift System including in the north of the volcanic rocks of Lake Chad and the Tibesti Volcanic Province. The influence of Cretaceous–Paleocene to Cenozoic mantle-derived magmatism initially identified in Cameroon and the western part of Chad might thus be extended northeastward, up to the northern part of Ouaddaï massif, on both sides of the positive gravity anomaly of the “Poli–Ounianga–Kebir heavy line”. We proposed to defined this large SW–NE magmatic province as the Cameroon Chad Volcanic Line (CCVL). The Cretaceous–Paleocene to Cenozoic magmatic activity of the Cameroon-Chad Volcanic Line appears to be controlled by the opening of the Central Africa Rift System localized along the edges of Archean cratonic nuclei marked by tectonic reworking and accretion of juvenile Paleoproterozoic to Neoproterozoic crust.

8. Conclusion

In this contribution, we present the first petrographic, mineralogical and geochemical study of the Iriba basanites located in the northern part of the Ouaddaï massif. The Iriba basanites are composed of magnesian olivine, Ca-rich clinopyroxenes (diopside and augite), albite and spinel. They display sodic and alkaline affinities that are attributed to magmatic differentiation of a primary mantle-derived magma by fractional crystallization. The geochemical signatures of these basanites indicate an affinity with OIB and are consistent with a generation by a low degree of partial melting (2–4%) of HIMU-type mantle source containing residual garnet (4–8%), without any crustal contamination. The Iriba basanites are similar to an alkaline magmatic series emplaced along the Central Africa Rift System, active from the Cretaceous–Paleocene to the Cenozoic, belonging to the so-called Cameroon Chad Volcanic Line (CCVL).

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

The research has been financially supported by LithoCOAC project (CNRS, France), the IRN FALCoL (CNRS, France) and the participation of the French Embassy in Chad through the fellowship program “Séjour Scientifique de Haut Niveau (SSHN)”.

Acknowledgements

We thank Philippe de Parseval for his assistance with electron microprobe analyses. Fabienne de Parseval is also thanked for the confection of rocks thin sections. We gratefully acknowledge several anonymous reviewers for their critical and constructive comments of the manuscript.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier