1. Introduction

The Pennsylvanian–Cisuralian transition took place at the end of a long period of globally cold climates marked by glacial activity in the South Pole and during the early tectonic post-assembly of Pangaea (Ziegler, Scotese, et al., 1979; Simancas et al., 2005; Isozaki, 2009). In the tropical regions, the early Permian was marked by a general drying trend during a transition from a maximum glacial coverage (Late Palaeozoic Ice Age or LPIA) to greenhouse conditions following a glacial recession at the Mississippian–Pennsylvanian boundary (Fielding et al., 2008; Montañez and Poulsen, 2013). In western Europe, a progressive aridification reaches its maximum around the Kungurian–Roadian boundary and was followed by a seasonal dry climate during the Guadalupian and until the Permo–Triassic boundary (Schneider et al., 2006; Montañez, Tabor, et al., 2007; Tabor and Poulsen, 2008; Lopez et al., 2008; Gulbranson et al., 2015; Michel et al., 2015).

This global climate evolution is recorded worldwide in the palaeofloras. For example, in western Europe, the Pennsylvanian continental vegetation (i.e., “Stephanian flora”) composed of pteridosperms, marattialean ferns, lycopsids, calamiteans, and cordaiteans trees (Doubinger, Vetter, et al., 1995; DiMichele, Tabor, et al., 2006; Thomas and Cleal, 2017) is mostly replaced by conifers and other gymnosperms corresponding to a meso-xerophytic flora (the “Autunian flora”), better adapted to drier conditions which became progressively predominant in the Permian palaeoenvironments (e.g., Lemoigne and Doubinger, 1984; DiMichele, Mamay, et al., 2001; Looy, Kerp, et al., 2014).

New radiometric data based on U–Pb analyses by Chemical Abrasion-Isotopic Dilution Ionisation Mass Spectrometry (CA-ID-TIMS) on zircon grains from tonsteins interbedded in lacustrine deposits have been recently published by Pellenard et al. (2017) in the Autun Basin (Figure 1A) with the aim to resolve the puzzling stratigraphical location of the Carboniferous–Permian boundary and to date the lower Autunian (i.e., Igornay and Muse formations). Subsequently, the Autunian series within the Autun Basin (France) provides an essential framework to study the changes in the vegetation succession observed during the Carboniferous–Permian transition. The objective of this paper is therefore to complete the previous palynological data after new detailed investigations in the Muse oil-shale beds (MOSB) within the Muse Formation (lower Autunian) using (1) the new established stratigraphical framework and (2) an alternative palynological method based on hydrogen peroxide (Riding et al., 2010). Our new results lead to a detailed palaeoenvironmental reconstruction based on palynology for the Autunian continental series in the global climate and geodynamic changes affecting the Carboniferous–Permian transition.

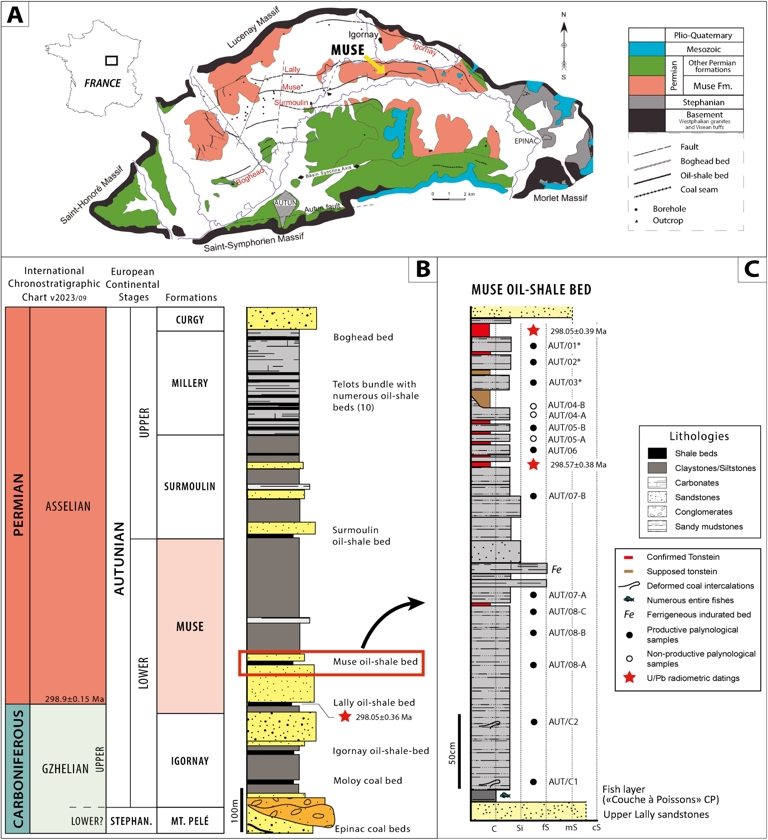

(A) Geographical and geological map of the Autun Basin (modified from Gand, Châteauneuf, et al., 2007). (B) Lithostratigraphy of the lower and upper Autunian in the Autun Basin with approximate thickness of the main formations, including oil shale beds (OSB) as valuable key markers (modified from Pellenard et al., 2017). (C) Stratigraphic log of the Muse OSB (modified from Pellenard et al., 2017). The palynological samples with the asterisk are low in relative abundance (counting <200 palynomorphs). Radiometric datings reported with full uncertainties. Masquer

(A) Geographical and geological map of the Autun Basin (modified from Gand, Châteauneuf, et al., 2007). (B) Lithostratigraphy of the lower and upper Autunian in the Autun Basin with approximate thickness of the main formations, including oil shale beds (OSB) as valuable ... Lire la suite

2. Stratigraphical and Geological setting

2.1. Stratigraphy of the Regional Continental Autunian Stage

In the Autun Basin (Figure 1A), the continental Autunian stratotype is divided into lower and upper Autunian (Figure 1B; sensu Pruvost, 1942). The lower Autunian units encompass the Igornay and Muse formations, while the upper Autunian corresponds to the Surmoulin, Millery and Curgy formations (Feys and Greber, 1972; Marteau, 1983; Chèvremont et al., 1999). A synthesis of the stratigraphy and palaeobotany was proposed by Châteauneuf, Farjanel, Pacaud, et al. (1992), Châteauneuf, Farjanel, Galtier, et al. (1992). Additionally, the history of the Autunian stratotype and its geochronology according to the different “stages” or “formations” since the early 19th century was developed by Gand, Pellenard, et al. (2017).

After previous palaeobotanical studies (on both macroflora and palynomorphs), a late Gzhelian–early Sakmarian age was inferred for the regional continental Autunian Stage (e.g., Doubinger, 1956; Feys and Greber, 1972; Bouroz and Doubinger, 1977; Doubinger and P. Elsass, 1979; Châteauneuf and Farjanel, 1989; Broutin, Châteauneuf, et al., 1999; Gand, Galtier, Garric, et al., 2013). Moreover, Davydov et al. (2012), C. H. Henderson et al. (2012), and Gradstein et al. (2012), considered the Autunian as equivalent to the middle Gzhelian–Kungurian stages as proposed in the Geologic Time Scale 2012 (GTS2012). In contrast, Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez (2010) proposed to include the whole “Autunian regional substage” in the Gzhelian Stage (Upper Pennsylvanian) based on their findings in macroflora content succession. However, recent radiometric datings using the CA-ID-TIMS U/Pb method indicate an upper Gzhelian age for the Igornay Formation and a lower Asselian age for the Lally and Muse OSBs interval (Pellenard et al., 2017). This work also suggests to fix the Carboniferous–Permian boundary in the Lally OSB, near the base of the Muse Formation, using a CA-ID-TIMS U/Pb age of 298.91 ± 0.08 Ma (0.36 full uncertainty) from interbedded tonstein dating. Therefore, a likely Asselian age can be inferred in the lower section of the Muse Formation. Conversely, the Igornay Formation must be ascribed to the upper Gzhelian.

2.2. Geology of the Autun Basin

The Autun Basin (Figure 1A) holds significant prominence within the global array of Permian basins due to its well-known status as a reference stratigraphical sequence for the lower Permian continental strata, housing the renowned Autunian stratotype (Figure 1B). The Autunian deposits are mainly composed of coarse siliciclastic sediments (i.e., sandstones and conglomerates), with intercalated organic-rich claystone intervals and singular organic matter-rich horizons called oil-shale beds (OSBs), corresponding to a strictly deltaic-lacustrine system (e.g., Mercuzot, Bourquin, Beccaletto, et al., 2021; Mercuzot, Bourquin, Pellenard, et al., 2022). It is a well-studied area which was the subject of numerous stratigraphic and cartographic investigations (Manès, 1844; Delafond, 1889; Pruvost, 1947; Elsass-Damon, 1977; Châteauneuf, Farjanel, Feys, et al., 1980; Marteau, 1983; Marteau and Feys, 1989; Châteauneuf and Farjanel, 1989; Feys, 1988; Feys, 1991; Chèvremont et al., 1999). Since the 1980s, all these studies were mainly carried out during the mining inventory of the basin by the Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières (BRGM). Among them, the study of Marteau (1983) provides a tectonic, stratigraphical, and sedimentological synthetic framework of the Carboniferous–Permian deposits of the Autun Basin.

The Autun Basin is located in Morvan, northern Massif Central (France), with a W–E direction, elliptical shape and depressed to the granitic base of a volcano-sedimentary depositional environment (e.g., Marteau, 1983; Pellenard et al., 2017). This basin is a small half-graben with a present-day outcropping extension of about 260 km2 and an average altitude of 320 m. Middle Triassic sandstones overlie the Permian deposits in the centre of the basin, reaching a thickness of 458 m (e.g., Gand, Châteauneuf, et al., 2007; Gand, Steyer, Pellenard, et al., 2015; Pellenard et al., 2017). It is limited to the south by the Autun extensional fault, which was active during the Permian sedimentation in an extensive geodynamic context (Marteau, 1983; Châteauneuf and Farjanel, 1989). A second fracturing system, with radial faults perpendicular to the southern edge of the basin, caused progressive subsidence of the blocks towards the west, leading to a displacement of the depocenter in the same direction. This post-orogenic (late Variscan) extension affected many other French Permian and Carboniferous basins, including Blanzy-Le Creusot, Aumance, Lodève, Saint-Affrique and the Provence (Toutin-Morin, 1980; Châteauneuf and Farjanel, 1989; Faure, 1995; Faure et al., 2009).

The Muse OSB, located north of Autun (Figure 1A), has been a focus of study since the 19th century thanks to mining activities. The studied outcrop consists of 3.5 m of grey to black claystone and siltstone, with intercalations of fine-grained sandstone layers (Figure 1C). The internationally known “couche à poissons” (literally “fish bed”), discovered in 1811 (Brignon, 2014), is located at the base of this outcrop. It does not correspond to a single fossilised fish layer but small fossiliferous sequences (Gand, Steyer, Pellenard, et al., 2015). In addition, the Muse OSB became famous due to the discovery of the first temnospondyl of the Autun Basin: Onchiodon (“Actinodon”) frossardi (Gaudry) Werneburg and Steyer, 1999; “Protriton petrolei” = Apateon pedestris (Gaudry) Schoch 1992 (Steyer et al., 1998) and thousands of complete actinopterygian fish remains. Between 2010 and 2015, systematic excavations were headed by some of the authors of this paper (GG and JSS) to complete the knowledge of the palaeontological content and taphonomy of the Muse OSB (Gand, Steyer and Chabard, 2010; Gand, Steyer and Chabard, 2012; Gand, Steyer, Chabard, et al., 2014; Gand, Steyer, Pellenard, et al., 2015). These annual and international excavations led to the discovery of thin tonstein layers (Pellenard et al., 2017), as well as hundreds of fossil specimens. Concerning the palaeofauna, insects, possible annelids, acanthodians, sharks (orthacanthids), bony fish (aeduelliforms) and rare amphibian remains (a phalanx and a possible dermal bone) have been collected and are under study (Gand, Steyer and Chabard, 2010; Gand, Steyer and Chabard, 2012; Gand, Steyer, Chabard, et al., 2014; Gand, Steyer, Pellenard, et al., 2015; Gand, Pellenard, et al., 2017; Luccisano, Rambert-Natsuaki, et al., 2021; Luccisano, Cuny, et al., 2023).

2.3. Muse palaeobotanical background

In the Muse OSB, a detailed sampling through the sequence (Figure 1C) has been carried out by several authors during the last decades, and has documented vegetation dominated by marattialean ferns and cordaiteans, with subsidiary pteridosperms (peltasperms), medullosalean cycads, and sphenopsids. The Muse OSB contain plant remains identified by Desa Dordjevic in 2010 (Gand, Steyer and Chabard, 2010) and Isabel van Waveren (Van Waveren et al., 2012) and eventually completed by Galtier in Gand, Galtier, Broutin, et al. (2015): Lycopsida (Sigillaria sp., ?Sigillariophyllum), Equisetopsida (Asterophyllites sp., Calamites sp., Calamostachys sp., Sphenophyllum sp., Sphenophyllostachis sp.), Filicopsida (Pecopteris (=Asterotheca) arborescens, Pecopteris unita, Pecopteris sp., Dizeugotheca sp., Scolecopteris sp.), Pteridospermopsida (Neuropteris planchardii, Neuropteris cf. heterophylla, Neuropteris sp., Alethopteris sp., Callipteridium sp., Callipteris sp. (Autunia sp.), Linopteris sp., Odontopteris sp., Sphenopteris sp.) Cordaitales (Cordaites principalis, Poacordaites sp., ?Cordaianthus) Coniferales (Walchia piniformis, ?Pseudovoltzia, ?Walchiostrobus), Cycadopsida and reproductive structures (medullosan and cordaitean) and seeds (Trigonocarpus sp., Rhabdocarpus sp., Carpolithes sp., Cardiocarpus cf. expansus, Cardiocarpus sp., Samaropsis sp., Pachytesta sp.). The presence of Taeniopteris multinervis (incertae sedis) is also reported.

During the inventory at the end of five successive palaeontological excavations, ca. 600 plant specimens have been collected in the Muse OSB (ibid.). The quantitative analysis showed lycopsids (1%), equisetopsids (14%), ferns (20%), pteridosperms (9%), Cordaites (18%), conifers (2%), and cycadoids (1%), as well as incertae sedis (1%), seeds (30%), and woods (3%). During the palaeontological excavations carried out in 2010, the following taxa were observed in the upper levels of the outcrop (between tonstein GI and GV, Figure 1C): Calamites (38%), Cordaites (9%), ferns and pteridosperms (15.5%), of which Pecopteris was dominant, while Walchia piniformis and Alethopteris were both uncommon (1% or less) (ibid.).

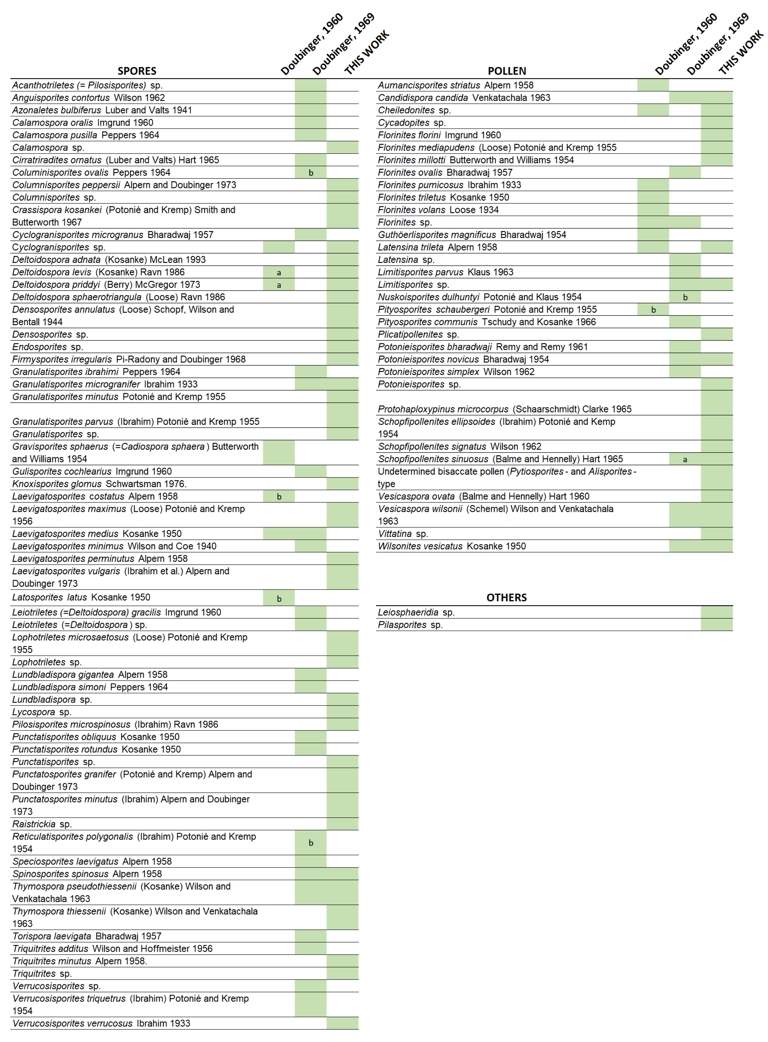

Few works were focused on the palynology of the Muse OSB before: Doubinger (1960) first identified a preliminary assemblage with a more detailed study later in Doubinger (1969). Doubinger and F. Elsass (1975), Doubinger and P. Elsass (1979) applied a quantitative analysis to the latter palynological assemblage (Doubinger, 1969) and compared it with others from the Autun Basin. Unfortunately, these are isolated samples lacking a detailed stratigraphic location. In all these, the dominant elements are the monosaccate (in particular Potonieisporites, Wilsonisporites, and Florinites) and bisaccate (i.e., Vesicaspora) gymnosperms, while the main pteridophyte representative is Lundbladispora, frequently found in tetrads. Although scarce, prasinophycean algae (i.e., Tasmanites sp.) were also identified, which, according to the authors, may have problematic palaeoenvironmental implications (Doubinger and F. Elsass, 1975).

3. Material and methods

Fifteen samples were collected from the Muse OSB (Figure 1C). The samples were processed at the laboratory of the University of Vigo using the standard palynological technique described by Wood et al. (1996), consisting in HCl–HF–HCl acid digestion. This method consists in the addition of HCl and HF to dissolve carbonate and silicate minerals.

The bituminous characteristic of the samples hindered palynomorph isolation because these were usually overlapped by flocculent organic remains. For this reason, we decided to use an alternative method of palynological preparation procedure, including hydrogen peroxide (Riding et al., 2010). This experimental technique consisted of boiling in H2O2 (30%) the rock sample previously fragmented between 1 and 2 mm to disaggregate the organic matter, leading to obtain different fractions after successively 2, 5, 10, and 20 min. Then, evaluating the sample under the microscope is necessary to choose the fraction with a better balance between conservation and the number of palynomorphs. The oxidising character of the H2O2 and the heat of boiling are adequate to eliminate organic remains, yet less aggressive than the nitric acid technique used for these cases (Traverse, 2007). After 5–10 min, the sample fraction is diluted in 1 litre of water. A dispersing agent (sodium hexametaphosphate, (NaPO3)6) was added to facilitate filtering and sieving at 10 μm, and the residue was eventually smeared in glass slides with a mounting medium of acrylic adhesive Loctite AA 350. These palynological slides were analysed under a Leica DM 2000 LED incorporated with a Leica ICC50 W camera at the University of Vigo.

A quantitative analysis was also carried out on all positive samples (see Supplementary Material). At least 200 specimens per sample were counted to estimate the relative abundance of each taxon in the whole Muse OSB section, a standard practice in palynology that ensures statistically meaningful results for common taxa and minimises errors in relative abundance estimates (ibid.). Samples with less than 200 palynomorphs were excluded for the palaeoecological interpretation. Although the data are shown in percentages, they should be considered qualitative since taphonomic sorting might have obscured the signature of the original biocenoses. The assignation of each taxa to major taxonomic groups was based on Balme (1995), Doubinger and Grauvogel-Stamm (1971), Dimitrova et al. (2011), Looy and Hotton (2014), and DiMichele, Hook, et al. (2018).

4. Results

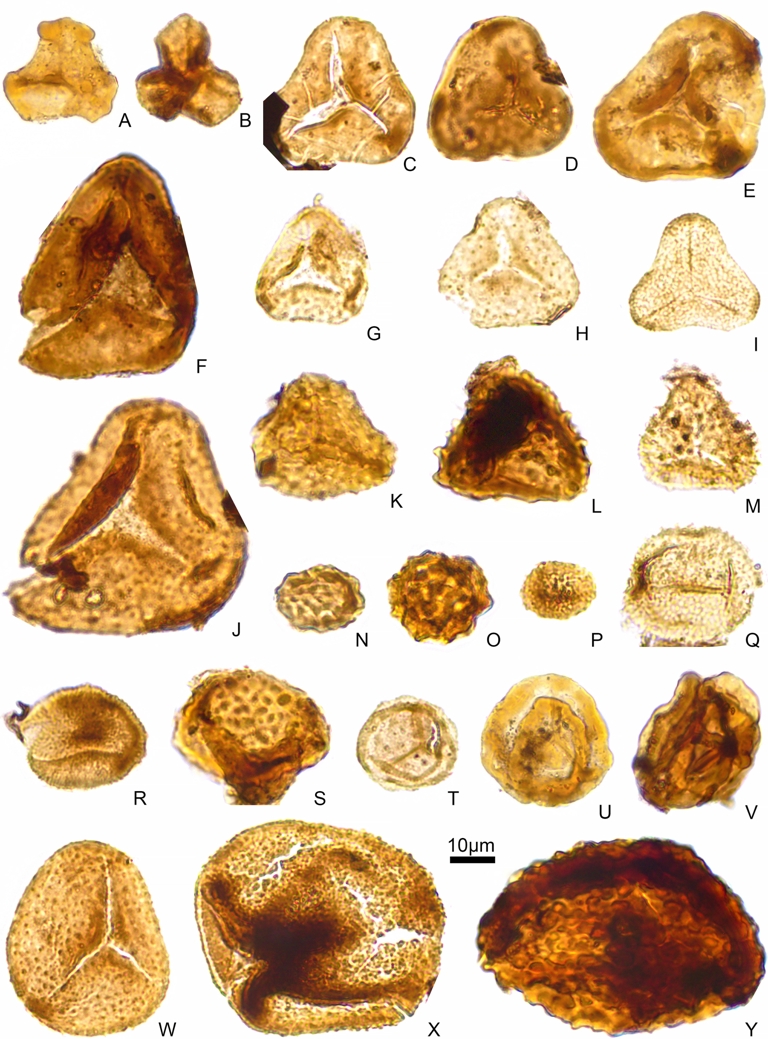

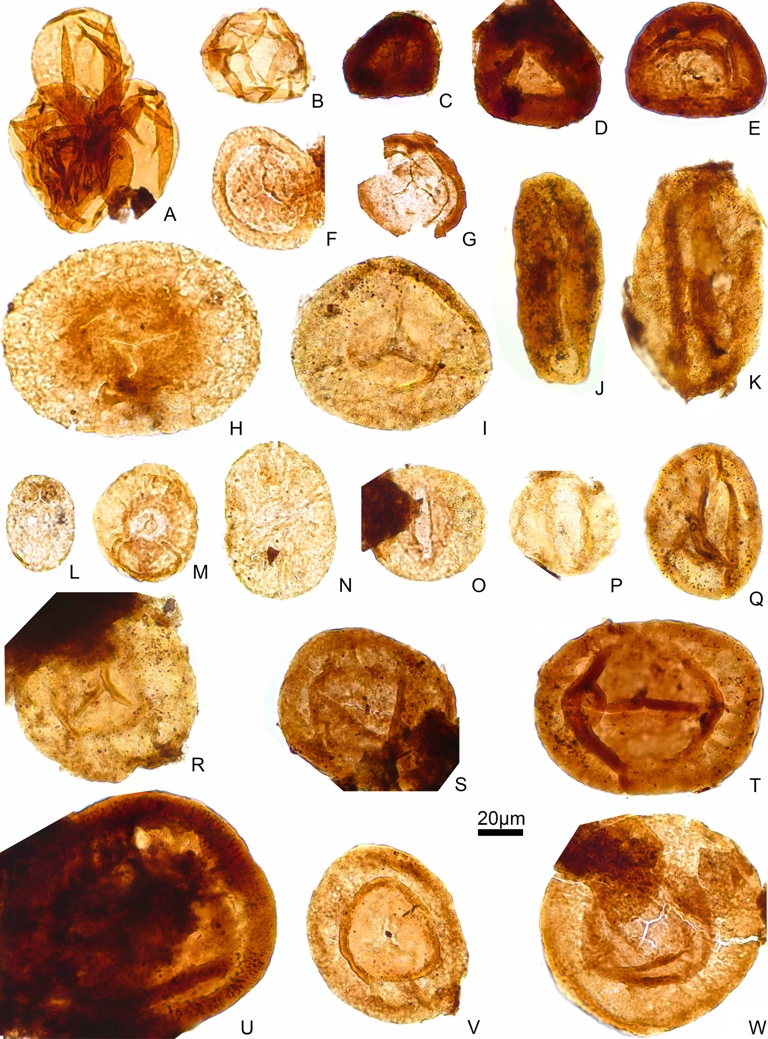

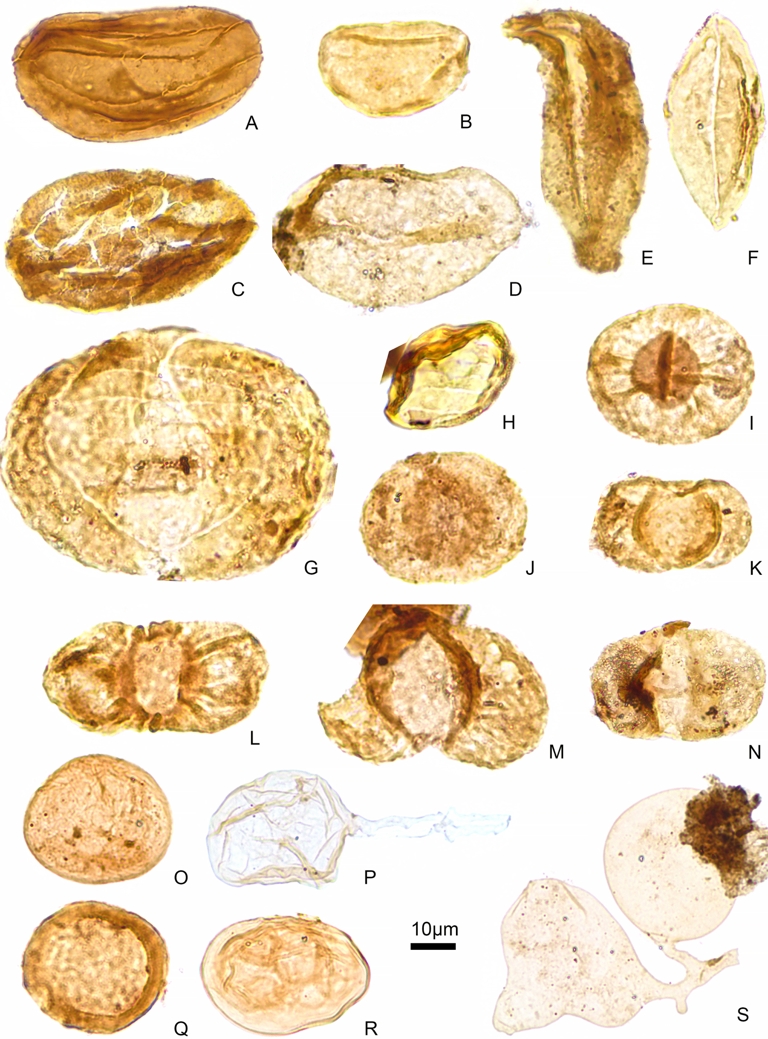

After the application of the alternative methodology, twelve palynological samples were productive (Figures 2–4), considering them as two different palynological assemblages according to their composition: Muse-A in the lower part and Muse-B in the middle-upper part of the Muse section. Both associations were as diversified as the ones from previous works (Doubinger, 1960; Doubinger, 1969; Doubinger and F. Elsass, 1975; Doubinger and P. Elsass, 1979) and throughout the entire Muse section, allowing, for the first time, a taxonomical (Figure 5) and quantitative evaluation (Figure 6). Moreover, several new species were identified belonging to 12 different genera that were found in the Muse OSB for the first time, including Crassispora, Densosporites, Endosporties, Firmysporites, Knoxisporites, Lophotriletes, Lycospora, Raistrickia, Cycadopites, Plicatipollenites, Protohaploxypinus, and Vittatina (Figure 5). The preservation grade was generally moderate except for the upper interval of the Muse-B (samples AUT/03 to AUT/01) which was low.

Muse-A and Muse-B palynological assemblages: (A) Triquitrites minutus. (B) Triquitrites sp. (C) Deltoidospora adnata. (D) Deltoidospora priddyi. (E) Deltoidospora levis. (F) Deltoidospora sphaerotriangula. (G) Granulatisporites minutus. (H) Granulatisporites parvus. (I) Granulatisporites microgranifer. (J) Granulatisporites sp. (K) Lophotriletes microsaetosus. (L) Lophotriletes sp. (M) Pilosisporites microspinosus. (N) Thymospora thiessenii. (O) Thymospora pseudothiessenii. (P) Punctatosporites minutus. (Q) Punctatosporites granifer. (R) Spinosporites spinosus. (S) Raistrickia sp. (T) Lycospora sp. (U) Knoxisporites glomus. (V) Firmysporites irregularis. (W) Cyclogranisporites sp. (X) Punctatisporites sp. (Y) Verrucosisporites verrucosus. Masquer

Muse-A and Muse-B palynological assemblages: (A) Triquitrites minutus. (B) Triquitrites sp. (C) Deltoidospora adnata. (D) Deltoidospora priddyi. (E) Deltoidospora levis. (F) Deltoidospora sphaerotriangula. (G) Granulatisporites minutus. (H) Granulatisporites parvus. (I) Granulatisporites microgranifer. (J) Granulatisporites sp. (K) Lophotriletes microsaetosus. (L) Lophotriletes ... Lire la suite

Muse-A and Muse-B palynological assemblages: (A–B) Calamospora sp. (C) Densosporites annulatus. (D) Densosporites sp. (E) Crassispora kosankei. (F) Latensina trileta. (G) Lundbladispora sp. (H) Candidispora candida. (I) Endosporites sp. (J) Schopfipollenites sinuosus. (K) Schopfipollenites signatus. (L) Florinites millotti. (M) Florinites mediapudens. (N) Florinites florini. (O) Vesicaspora wilsonii. (P) Vesicaspora ovata. (Q) Schopfipollenites ellipsoides. (R) Wilsonites vesicatus. (S) Potonieisporites novicus. (T) Potonieisporites sp. (U) Undetermined monosaccate. (V–W) Plicatipollenites sp.

Muse-A and Muse-B palynological assemblages: (A) Columnisporites peppersi. (B) Laevigatosporites perminutus. (C) Columnisporites sp. (D) Laevigatosporites vulgaris. (E) Cheiledonites sp. (F) Cycadopites sp. (G) Protohaploxypinus microcorpus. (H) Vittatina sp. (I–J) Undetermined monosaccate pollen. (K–M) Undetermined bisaccate pollen. (N) Limitisporites sp. (O) Undetermined freshwater algae. (Q) Pilasporites sp. (R) Leiosphaeridia sp. (P–S) Fungal structures.

Compilation of previously published and new taxa from the Muse OSB, Autun Basin, France. Labels, (a) synonym taxa, (b) confer.

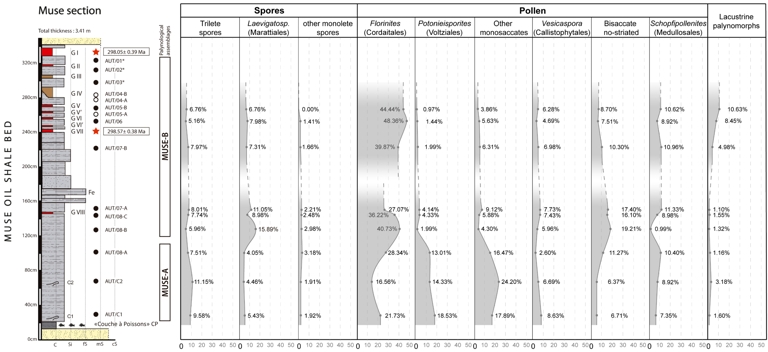

Quantitative analysis of the MUSE-A and MUSE-B assemblages from the Muse OSB (Muse section, Autun, France), focusing on the main palynological groups. Samples AUT/01-AUT/03 were not plotted due to its low relative abundance ( <200 palynomorphs). Legend for stratigraphic log in Figure 1.

The Muse-A assemblage is dominated by voltzialean and cordaitalean conifers (mainly Florinites, Potonieisporites, and other monosaccate pollen). To a lesser extent, pteridophytes (Lycopsida, Filicopsida, and Marattiopsida) and medullosalean cycads (Schopfipollenites) are also present.

The Muse-B assemblage highlights a clear dominance of cordaitalean conifers with Florinites (ca. 40–50%) to the detriment of the voltzialean palynomorphs. The presence of pteridophytes and pteridosperms remains relatively constant compared to Muse-A. It is also noteworthy the increase in lacustrine elements (i.e., prasinophycean algae) towards the upper part of the assemblage (Figure 6).

5. Discussion

5.1. The Muse OSB palaeoecology

5.1.1. Terrestrial plant community

According to these new results, conifers and pteridosperms are the main components of the Muse palynofloras with a high diversity and relative abundance of ca. 50% and ca. 20%, respectively (Figure 6). Although less abundant, pteridophytes are well represented through both lycophytes and ferns with a relative abundance of ca. 15%. As stated above, a division between the Muse-A and Muse-B assemblages has been established mainly due to significant differences in the type of conifers. In the Muse-A assemblage, Cordaitales (i.e., Florinites) and Voltziales (i.e., Potonieisporites) are the main conifer representatives. By constrast, in the Muse-B assemblage, Voltziales decrease dramatically, giving way to Cordaitales sole dominance. Although the observed increase in mean particle size in the Muse-B assemblage (see Supplementary Material) may suggest a taphonomic overprint, we consider this an unlikely explanation for the observed shift in palynological composition. Notably, cordaitalean pollen—typically smaller than voltzialean pollen—becomes more abundant in the upper part of the section, while voltzialean pollen virtually disappears. Were hydrodynamic sorting the primary driver, one would expect a relative enrichment of larger pollen types, such as voltzialean Potonieisporites, in the upper levels of the section. However, this pattern is not observed. This inverse relationship suggests that the compositional change is unlikely to be taphonomically controlled and may instead reflect broader environmental or vegetational changes. In any case, the Cordaitales conifers, seed ferns, cycads, and pteridophyte spores apparently constitute the autochthonous elements of the palynoflora, while the Voltziales conifers and other bisaccate pollens (such as Pityosporites or Alisporites) may be the allochthonous elements transported to the palaeo-lake corresponding to the Muse OSB.

These new results are consistent with previous palynological studies (Doubinger, 1960; Doubinger, 1969; Doubinger and F. Elsass, 1975; Doubinger and P. Elsass, 1979): in the Muse section, isolated samples also recorded assemblages with a predominance of monosaccate pollen corresponding to cordaitalean and voltzialean conifers and putative peltasmermalean seed ferns (Wilsonites), as well as lycophytes represented by Lundbladispora spores, frequently found in tetrads). It is noteworthy that several palynological zones were also differentiated by Châteauneuf, Farjanel, Pacaud, et al. (1992) based on comparative palynological data from the Autun Basin (Doubinger and P. Elsass, 1979).

The previous vegetal macro-remains found in the Muse OSB are generally similar to the palynological data (e.g., records of Sigillaria and Pecopteris; Doubinger, 1994). However, contrary to the palynological findings, conifer remains in the macroflora associations are few in the Muse OSB. A taphonomic bias could explain why silicified conifer wood has been discovered in the Lally upper sandstones Member within the base of the Muse Fm. (Figure 1B; Doubinger and Marguerier, 1975; Marguerier and Pacaud, 1980; Gand, Galtier, Broutin, et al., 2015). These fossil trunks show similar orientations and exhibit traces of abrasion on their surface (Marguerier and Pacaud, 1980), indicative of transport in running water (Gand, Galtier, Broutin, et al., 2015). It is suggested that the silicification process occurred near the growth site, and, in some cases, the trunks were preserved in the growth position (ibid.). According to Gand, Galtier, Broutin, et al. (ibid.), these remains belong to the Dadoxylon group of type II, which would correspond to walchian conifers (Voltziales; Doubinger and Marguerier, 1975), Metacordaites rigollotii and Scleromedulloxylon varollense, reflecting a high diversity. Also, close to the Muse locality, another type of Dadoxylon wood (Cordaixylon; related to Cordaitales) and silicified fragments of Psaronius, Arthropitys, and Sigillaria have been found (Broutin, Châteauneuf, et al., 1999; Gand, Galtier, Broutin, et al., 2015). Moreover, the compilation of the macroflora findings resulted in a classification of the floral associations by different ecological groups (Van Waveren et al., 2012): hygrophytic (e.g., Equisetopsida), hygro-mesophytic (Cordaites principalis, Neuropteris planchardii, and Asterotheca arborescens), and mesophytic plants (Walchia piniformis, Sphenopteris sp., Dicranophyllales, and Cycadopsida).

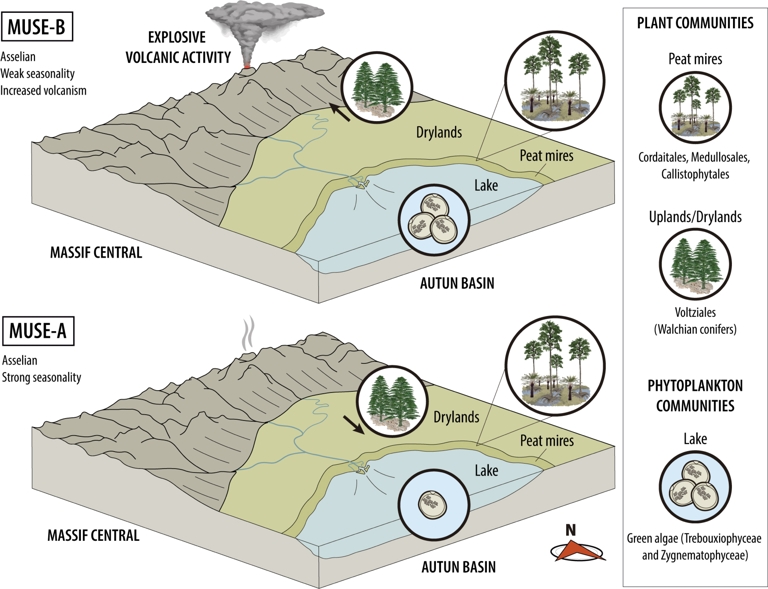

Therefore, after the integration of our new palynological data with the previous palaeobotanical studies, the Muse OSB plant community corresponds to a peat swamp forest dominated by cordaitalean and (occasionally) walchian conifers, with the presence of medullosalean cycads and callistophytalean seed ferns, as well as an understory of lycophytes and ferns (primarily marattialean). Surrounding this community, distant from the lake, a forest dominated by walchian conifers would also be present (Figure 7). According to the quantitative palynological analysis, the vegetation dynamics of the Muse OSB were apparently stable except for the Cordaitales, which increased towards the upper part of the unit in to the detriment of the Voltziales (Figure 6).

Palaeoecological reconstruction of the plant and phytoplankton communities in the Muse OSB.

5.1.2. Lacustrine phytoplankton community

Several aquatic palynomorphs were also found in both Muse-A and Muse-B assemblages with an increasing relative abundance upwards (Figure 6). Some of these elements resembling Leiosphaeridia (Figure 4R) and Pilasporites (Figure 4Q) are present throughout the Muse OSB. Both taxa are polyphyletic due to their simple morphology but can be considered non-marine algae. In the case of Leiosphaeridia sp., it corresponds to green algae, which includes phycomatas of pyramimonadalean prasinophytes (primarily marine) or vegetative cells of Trebouxiophyceae (primarily non-marine) (Mays et al., 2021). Pilasporites have been considered as vascular plant spore (Equisetales and Isoetales) or as zygospores of non-marine green algae (Zygnematophyceae), the latter affinity being the most likely according to algae co-occurrence and its morphology (ibid.).

In previous palynological studies, the presence of prasinophycean algae was also observed. Due to their marine affinity, these algae had controversial implications for the palaeoenvironmental interpretation (i.e., Tasmanites sp.; Doubinger and F. Elsass, 1975). However, non-marine prasinophycean species also exist (Traverse, 2007), allowing the presence of Tasmanites-like palynomorphs without marine influence. Moreover, the exclusively marine nature of Tasmanites is currently under debate, as these algae have recently been found in Permian freshwater lacustrine deposits in East Timor (Lelono, 2019). In any case, we consider the Tasmanites present in Doubinger and F. Elsass (1975) as Pilasporites instead, after comparing their illustration (ibid., plate 1, Figure 15) to ours (Figure 4Q). This re-assignation would be consistent with the purely freshwater lacustrine environment corresponding to the Autun Basin (e.g., Gand, Châteauneuf, et al., 2007; Gand, Steyer, Pellenard, et al., 2015; Mercuzot, Bourquin, Pellenard, et al., 2022; Luccisano, Cuny, et al., 2023).

5.2. Palaeoecological and palaeoenvironmental implications

Beginning with the Carboniferous–Permian transition, the early to late Permian exhibits a progressive climate shift towards more arid conditions and a subsequent succession of floras adapted to wetland first, seasonally dry then, and, eventually, arid with a wet season (Broutin, Doubinger, et al., 1990; DiMichele and Aronson, 1992; Falcon-Lang, 2003; DiMichele, Tabor, et al., 2006). However, the earliest Permian plant communities usually present transitional floras with Carboniferous and Permian characteristics. Several pteridophytes belonging to the Carboniferous-type wetland biome (Juncal et al., 2019) were found in the Muse palynofloras. In addition, medullosalean cycads and callistophytalean seed ferns, also typical Carboniferous elements, have a common occurrence in the Muse palynological assemblages.

The presence of these wetland elements together with xerophytic Permian elements (i.e., Voltziales) indicates that the Autun Basin remained under the influence of a seasonally dry climate, but maintaining enough moisture for the persistence of these hygrophytes during at least ∼300 ky in the early Asselian. These environmental conditions allowed plants producing Densosporites, Punctatosporites, Spinosporites, and Thymospora to survive in a context of instability and gradual evolution to drier conditions throughout the Permian Broutin (1986), Juncal et al. (2019).

However, the main plants in the Muse section are xerophytic or tolerant to drier climates, as is the case of the conifers (Lyons and Darrah, 1989). The best example is walchian conifers (Voltziales), which were restricted to seasonally dry habitats and considered as a marker of semi-arid floras (Ziegler, Rees, et al., 2002; DiMichele, Cecil, et al., 2010). The Cordaitales, also typical of seasonally dry conditions (Kerp, 1990; Algeo and Scheckler, 1998), were usually adapted to wetter environments than walchian conifers (Bashforth et al., 2014). In this case, they inhabited lowland peat mires where they formed mostly monotypic stands or were part of heterogeneous vegetation thriving interspersed among arborescent ferns (such as Calamites) and lycophytes (Raymond and Phillips, 1983; Trivett and Rothwell, 1991; Raymond, 1988; DiMichele and Phillips, 1994).

Walchian conifers were exclusively related to topographically high environments (e.g., Rothwell and Mapes, 1988). However, recent Palaeozoic studies on vegetation dynamics noticed that variation in walchian dominance was not affected by topographical changes but by climatic shifts between wet and dry conditions (Falcon-Lang et al., 2009; Dolby et al., 2011; DiMichele, 2014). Therefore, the differences between the Muse-A and Muse-B assemblages related to the conifer composition may reflect climate change. The walchian conifers may be established as a permanent community in distant parts, which may be topographically higher (allochthones in Muse-A and Muse-B assemblages; Figure 7), while they expanded towards the communities closer to the palaeo-lake during drier phases due to more marked seasonality (parautochthonous in Muse-A assemblage; Figure 7).

This trend is observed throughout the latest Carboniferous–early Permian transition, based on the palynological biozones established for the Autun Basin (Châteauneuf, Farjanel, Pacaud, et al., 1992). After a pronounced decrease of spores since the late Carboniferous, walchian-pollen (Potonieisporites) settles as one of the main components of the early Permian palynofloras. In the case of Cordaitales pollen (Florinites), it was present since the latest Carboniferous remaining solid as a main component throughout the early Permian. There is an inversely proportional relationship between these two floral components in the same ecological niche. The higher the proportion of Walchian pollen, the lower the proportion of Cordaitales, and vice versa. As we have seen, this was most likely influenced by climate. This pattern was also found during the Pennsylvanian Coal Age, suggesting an increase in seasonality when walchian conifers dominated (DiMichele, 2014). Therefore, in the Autun Basin, the walchian-cordaitalean pollen relation may be used as a proxy for seasonality.

Another significant aspect of Muse palaeoecology is related to the lacustrine phytoplankton community. As mentioned before, the quantitative analysis of the lacustrine elements in the Muse OSB exhibits an increase towards the upper part of the Muse-B assemblage (Figures 6–7). This green algae maximum interval corresponds to a sequence of tonstein occurrence (Figure 1C) and, therefore, to a period of active explosive volcanism (Pellenard et al., 2017). Volcanic ash affects the nutrient and light availability in marine and freshwater algae communities, frequently producing phytoplankton blooms or enhanced growth (e.g., Hamme et al., 2010; Modenutti et al., 2013; Browning et al., 2014). Consequently, the increase in the relative abundance of green algae in the Muse section may be related to enhanced growth of the lacustrine phytoplankton community after a more active volcanic period. It is worth noting that sample AUT/07A, located directly above one of the volcanic layers (GVIII), shows a notably low proportion of lacustrine palynomorphs. This exception may reflect local taphonomic or environmental conditions (e.g., limited water availability or rapid burial), which may have restricted phytoplankton development despite the potential nutrient input. However, the overall trend across Muse-B remains consistent with a volcanically induced productivity pulse.

6. Conclusions

The understanding of the Muse Formation in the Autun Basin, France, has significantly advanced through ongoing palaeontological investigations and geological analyses spanning back to the 19th century. In this regard, a comprehensive reassessment of prior palaeobotanical inquiries has been undertaken alongside a novel taxonomic and quantitative palynological examination across the entire Muse Formation. These endeavours aim to elucidate the fluctuations in floral composition within the predominantly lacustrine sediments of this formation.

The plant community corresponding to the Muse OSB is identified as a peat swamp forest characterised by a prevalence of cordaitalean conifers. Additionally, this community gathers medullosalean cycads and callistophytalean seed ferns, complemented by an undergrowth comprising lycophytes and ferns (including marattialean species). Adjacent to the lake and topographically higher, a forest dominated by walchian conifers (Voltziales) would also be present.

The vegetation dynamics of the Muse OSB would be relatively stable, except for the Cordaitales, which exhibit an increment towards the top of the unit to the detriment of the Voltziales. This pattern, also observed throughout the Autun Basin deposits, could be related to an increase of wetter conditions. However, taphonomical or preservation factors should not be excluded. Moreover, the persistence of palynomorphs belonging to the Carboniferous wetland biome indicates the presence of environments with enough moisture for the survival of hygrophyte plants in the Autun Basin for at least ∼300 ky after the Carboniferous–Permian boundary.

The phytoplankton community consisted of green algae, including Trebouxiophyceae and Zygnematophyceae. A higher relative abundance was observed in the upper part of the Muse OSB, corresponding to enhanced growth of this community that was likely affected by increased nutrient availability due to enhanced distal explosive volcanism.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organisation that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organisations.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the constructive suggestions of the editor Dr. Sylvie Bourquin, as well as the two anonymous reviewers. This research was partially financed by the Ministerio de Ciencia y Innovación of the Spanish Government (ref.: PID2022-141050NB-I00), and the research project “CALDERA - CALibrating a Deglaciation ERA: Decline of the Late Palaeozoic Ice Age and its consequences for tropical terrestrial ecosystems” financed by the Promotion of Educational Policies, University and Research Department of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano - South Tyrol (CUP H33C23001340003).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0