1 Introduction

Numerous paleoclimate records from Greenland ice cores, North Atlantic marine sequences and northern European terrestrial sequences indicate that the last glacial-interglacial transition was punctuated in the North Atlantic region by abrupt climate changes (e.g. Bard et al., 1987; Björck et al., 1996; Dansgaard et al., 1993; Lehman and Keigwin, 1992; NGRIP members, 2004). In order to improve our understanding of the wider impacts of this perturbation of the North Atlantic climate and the mechanisms underlying the transmission of climate changes, several paleoclimate records are required. In this respect, the Mediterranean Sea is considered as a key region, thanks to its miniature dimension, its close atmospheric and oceanic linkages to the North Atlantic region and its teleconnection with African and Asian monsoon (Lionello et al., 1996).

The millennium cooling of the Younger Dryas constitutes the most recent brutal cold event which interrupted the onset of the postglacial warming occurred since 15 ka cal. BP. It is widely accepted that the Younger Dryas cold episode resulted from an abrupt reduction in the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation occasioned by a massive influx of freshwater. Until recently, the prevailing view ascribed the source to meltwater drainage around the southern and eastern margins of the warming Laurentide Ice Sheet through the St. Lawrence Seaway (Teller et al., 2002) or in the Canadian Arctic Ocean (Murton et al., 2010). However, several studies have found little geomorphological, chronological or paleoceanographic support for such a connection at the onset of the Younger Dryas (Broecker, 2006; de Vernal and Hillaire-Marcel, 1996; Keigwin and Jones, 1995; Lowell et al., 2005).

The aim of this paper is to reconstruct the paleoenvironmental changes during the last glacial-interglacial transition on the basis of studying the main dinocyst species in three deep-marine sequences from the western Mediterranean Sea. This proxy was widely studied in the North Atlantic (de Vernal and Hillaire-Marcel, 2006; de Vernal et al., 1992, 1994, 2005; Eynaud et al., 2004; Harland and Howe, 1995; Marret et al., 2004; Rochon et al., 1998; Turon, 1978, 1981a,b) but remains poorly developed in the western Mediterranean in spite of the original results obtained by the previous studies in this basin (Beaudouin et al., 2007; Combourieu-Nebout et al., 1999; Sangiorgi et al., 2002; Turon and Londeix, 1988). The choice of this proxy is to complement and improve our understanding of climatic abrupt changes during the last deglaciation and extend our knowledge about the ecology of several dinoflagellate taxa in the Mediterranean Sea. Moreover, we discuss the distribution of Nematosphaeropsis labyrinthus and compare our data to those of previous studies in the same basin.

2 Material and environmental setting

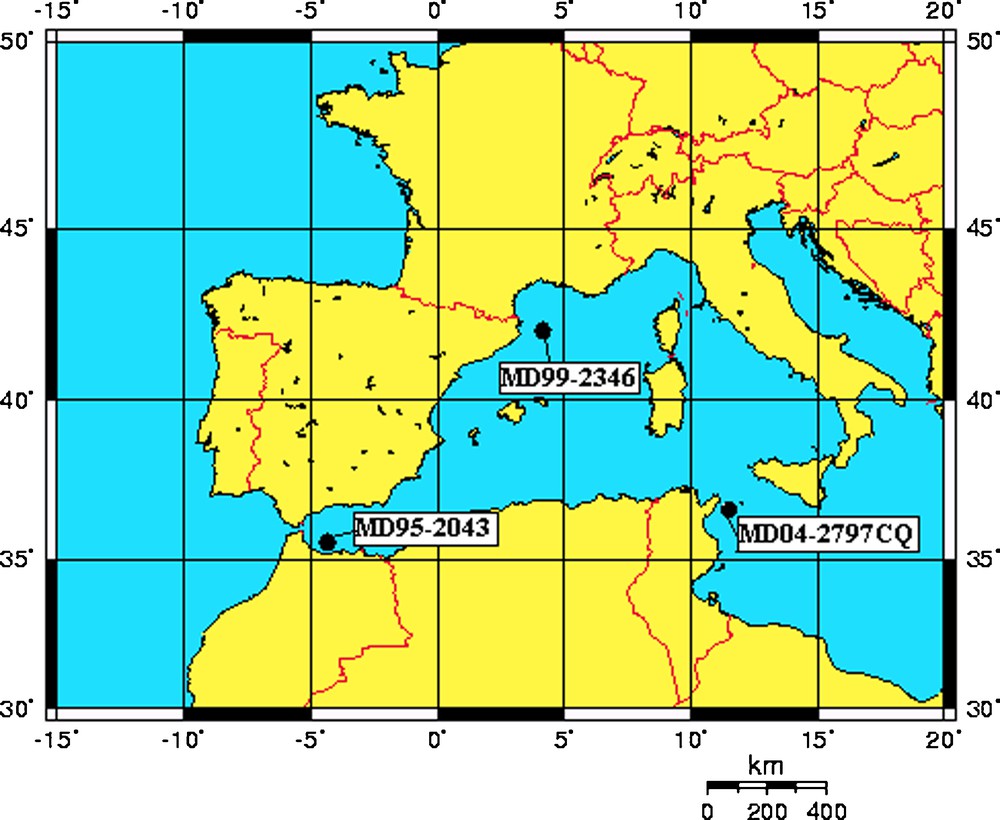

The cores (MD04-2797, MD95-2043, MD99-2346) were collected during expeditions of the Marion-Dufresne (Fig. 1; Table 1). Samples were taken every 10 cm and at a higher resolution during the marine isotopic stage 1 of the MD99-2346 because of its lower sedimentation rate.

Location of the studied cores (Table 1) in the western Mediterranean Sea.

Localisation des carottes étudiées (Tableau 1) en Méditerranée occidentale.

Informations géographiques sur les carottes étudiées.

| Location | Core | Water depth (m) | Latitude | Longitude |

| Sicilian-Tunisian Strait | MD04-2797CQ | 771 | 36°57′N | 11°40′E |

| Alboran Sea | MD95-2043 | 1841 | 36°09′N | 02°37′W |

| Gulf of Lions | MD99-2346 | 2090 | 42°05′N | 04°15′E |

The Mediterranean Sea is a semi-enclosed marginal basin, connected with the Atlantic Ocean through the strait of Gibraltar. It is subdivided into western and eastern sub-basins by the Sicilian-Tunisian Strait. Situated in the sub-tropical region, the Mediterranean Sea receives much solar radiation. An excess of evaporation over precipitation furthermore results in a strong salinity increase from west to east (Béthoux, 1979; Wüst, 1961). Net buoyancy loss maintains a two-layer flow regime through the strait of Gibraltar, consisting of Atlantic surface water inflow and Mediterranean subsurface water outflow (Béthoux et al., 1998).

Relatively dense water masses are formed and sink to a great depth in very specific regions of the Mediterranean Sea such as the Gulf of Lions where Western Mediterranean Deep Water (WMDW) is formed (Lacombe et al., 1985). The eastern Mediterranean Sea has two main convection cells, one in the Levantine Basin where Levantine Intermediate Water (LIW) forms and the other in the Adriatic Sea (sometimes switching to the Aegean Sea) where the Eastern Mediterranean Deep-Water (EMDW) forms. Deep-water overturning is controlled by regional evaporation but also by the local wind systems over these areas. In the western Mediterranean Sea (our study region), the flow of relatively dry and cold north winds in the Gulf of Lions (the Mistral from the north and the Tramontane from the west/northwest) intensifies water evaporation and promotes cooling but also adds kinetic momentum, which allows water to sink (Lacombe et al., 1985; Miller, 1983; Millot, 1990) and formed (WMDW). As a consequence, changes in the intensity of these overturning Mediterranean cells can provide a good diagnosis of the dominant climatic conditions in this region. These Mediterranean water masses are also relevant to the North Atlantic Ocean as they export the Mediterranean Outflow Water (MOW) that is fed by a mixture of modified LIW and WMDW.

3 Methods

3.1 Age model

The chronology of the three marine cores was established on the basis of AMS-14C dates on planktonic foraminifera (Tables 2–4). The conventional 14C ages have been calibrated in calendar years using the Calib 5.01 program (Stuiver et al., 1998) and the marine calibration dataset of Hughen et al. (2004). The precise spatial and temporal patterns of change in paleoreservoir age are not fully understood, and therefore we have applied a uniform reservoir correction of −400 years (Bard, 1988; Siani et al., 2001). The age models were determined from interpolation between the calibrated ages. In addition to radiocarbon ages, a stratigraphical correlation between the δ18O curves for G. bulloides of the core MD04-2797CQ and the dated core MD95-2043 (Cacho et al., 1999) was used to establish the age models of the MD04-2797CQ (Rouis-Zargouni et al., 2010). Data are presented here against a calibrated chronology. Mean uncertainty on ages is estimated to be about 500 years.

Modèle d’âge de la carotte MD95-2043 (Mer d’Alboran), basé sur 17 âges radiocarbone calibrés selon Calib.5.01 (Cacho et al., 1999).

| Depth (cm) | Age 14C (BP) | Error | Sample | Age (cal. BP) | |

| 14 | 1000 | Extrapolation | |||

| 54 | 1980 | 60 | G. bulloides | 1540 | Calib 5.01 |

| 96 | 3216 | 37 | G. bulloides | 3030 | Calib 5.01 |

| 178 | 4275 | 41 | G. bulloides | 4390 | Calib 5.01 |

| 238 | 5652 | 42 | G. bulloides | 6060 | Calib 5.01 |

| 298 | 6870 | 50 | G. bulloides | 7380 | Calib 5.01 |

| 348 | 8530 | 47 | N. pachyderma | 9170 | Calib 5.01 |

| 418 | 9200 | 60 | G. bulloides | 10,010 | Calib 5.01 |

| 487 | 9970 | 50 | N. pachyderma | 10,940 | Calib 5.01 |

| 512 | 10,560 | 60 | N. pachyderma | 11,800 | Calib 5.01 |

| 588 | 10,750 | 60 | N. pachyderma | 12,170 | Calib 5.01 |

| 595 | 11,590 | 60 | N. pachyderma | 13,090 | Calib 5.01 |

| 682 | 11,880 | 80 | N. pachyderma | 13,330 | Calib 5.01 |

| 708 | 12,790 | 90 | G. bulloides | 14,410 | Calib 5.01 |

| 758 | 13,100 | 90 | G. bulloides | 14,970 | Calib 5.01 |

| 802 | 14,350 | 110 | N. pachyderma | 16,620 | Calib 5.01 |

| 858 | 15,440 | 90 | N. pachyderma | 18,330 | Calib 5.01 |

| 18,260 | 120 | N. pachyderma | 21,090 | Calib 5.01 |

Modèle d’âge de la carotte MD04-2797 CQ (détroit entre Sicile et Tunisie) (Rouis-Zargouni et al., 2010), basé sur l’interpolation de six âges radiocarbone convertis en âges calendaires par utilisation de Calib. 5.01 et la corrélation entre δ18O (enregistré sur Globigerina bulloides dans la carotte MD04-2797 CQ) et δ18O enregistré dans la carotte datée MD95-2043 (Cacho et al., 1999).

| Depth (cm) | Age 14C (BP) | Error | Sample | Age (Cal. BP) | |

| 0 | 1105 | 20 | G. inflata | 662 | Calib 5.01 |

| 40 | 2508 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 120 | 4770 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 140 | 5990 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 160 | 6764 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 200 | 7465 | 30 | Globigerinoïdes ruber | 7929 | Calib 5.01 |

| 330 | 8965 | 30 | Globigerinoïdes ruber | 9380 | Calib 5.01 |

| 370 | 10,715 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 470 | 12,605 | 40 | G. inflata | 14,058 | Calib 5.01 |

| 490 | 15,498 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 511 | 13,800 | 100 | G. bulloides | 15,909 | Calib 5.01 |

| 560 | 17,080 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 610 | 15,590 | 50 | G. bulloides | 18,617 | Calib 5.01 |

| 700 | 21,660 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 910 | 25,530 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 960 | 27,180 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 970 | 27,960 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 1010 | 28,640 | MD95-2043 | |||

| 1030 | 29,110 | MD95-2043 |

Modèle d’âge de la carotte MD99-2346 (Golfe du Lion), basé sur 11 âges radiocarbone calibrés selon Calib. 5.01.

| Depth (cm) | Age 14C (BP) | Error | Sample | Age (Cal. BP) | |

| 0 | 0 | Extrapolation | |||

| 30 | 3535 | 30 | G. bulloides | 3418 | Calib 5.01 |

| 46 | 4830 | 50 | G. bulloides | 5128 | Calib 5.01 |

| 160 | 10,830 | 35 | G. bulloides | 12,329 | Calib 5.01 |

| 280 | 12,370 | 35 | G. bulloides | 13,821 | Calib 5.01 |

| 340 | 13,025 | 35 | G. bulloides | 14,888 | Calib 5.01 |

| 370 | 13,295 | 45 | G. bulloides | 15,219 | Calib 5.01 |

| 435 | 14,010 | 90 | G. bulloides | 16,191 | Calib 5.01 |

| 579 | 16,330 | 110 | G. bulloides | 19,115 | Calib 5.01 |

| 690 | 17,820 | 45 | G. bulloides | 20,553 | Calib 5.01 |

| 748 | 18,400 | 130 | G. bulloides | 21,313 | Calib 5.01 |

| 880 | 20,750 | 150 | N. pachyderma sinistral | 24,354 | Calib 5.01 |

3.2 Dinoflagellate cysts analysis

Dinocyst analysis was performed on the fraction < 150 μm. The palynological processing followed the procedure described by de Vernal et al. (1996) and Rochon et al. (1999), slightly modified at the UMR-EPOC laboratory (www.epoc.u-bordeaux.fr/equipethematique_paleo/Outils). After chemical treatments (cold 10, 25 and 50% HCl, cold 40 then 70% HF shaken during 24 h), the samples were sieved through a single use 10 μm nylon mesh screens. Acetolysis was not used to avoid the destruction of polykrikacean and protoperidiniacean cysts (Marret, 1993; Turon, 1984). The final residue was mounted with glycerine jelly coloured with fuschin. Dinocysts were counted using a Zeiss Axioscope light microscope at 400 ×. An average of 100 to 300 dinoflagellate cysts were identified and counted from each sample. References for dinocyst identification are based on studies from Turon (1984) and de Vernal et al. (1992). The dinocyst taxonomy is generally in agreement with that cited in Fensome and MacRae (1998). Dinocyst concentrations were calculated using the marker grain method (de Vernal et al., 1996) based on aliquot number of Lycopodium spores.

C = Dinocyst concentration (number of dinocysts/cm3);

N = number of palynomorph counted;

L = number of Lycopodium spores added during the treatment of the sample;

V = volume of sample (cm3);

I = number of Lycopodium spores counted.

4 Results

4.1 Overview of the dinocyst data for the last deglaciation

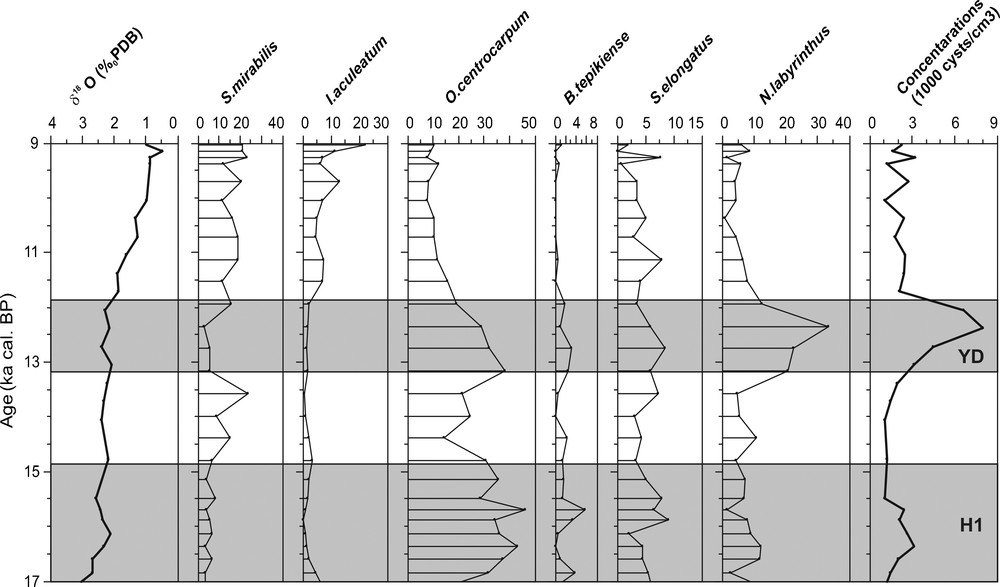

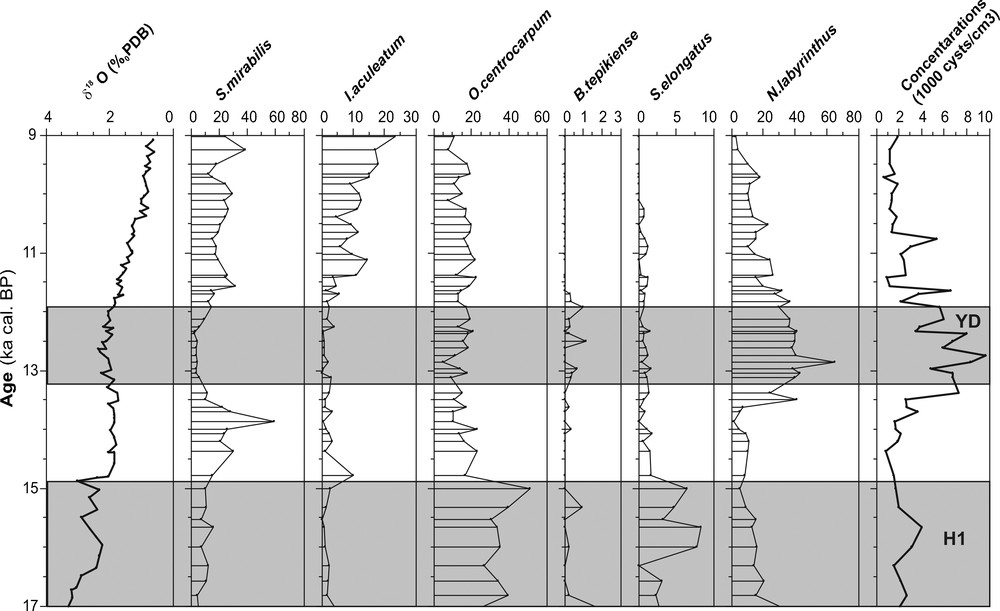

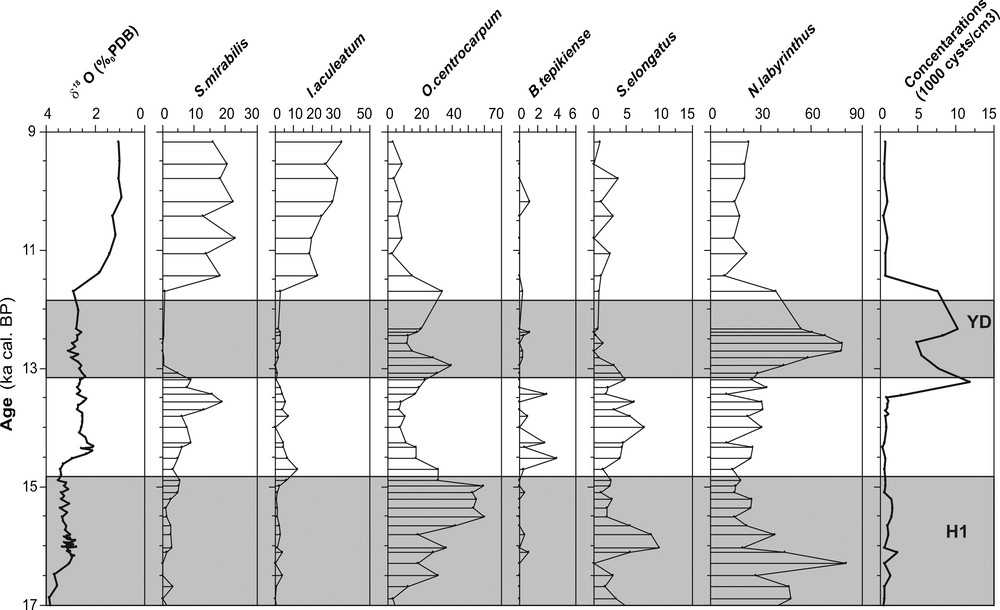

Dinocyst analyses in the studied sections are based on the identification of over 30 taxa. During the last deglaciation, our assemblages are dominated by O. centrocarpum, N. labyrinthus, Spiniferites mirabilis and Impagidinium aculeatum (Figs. 2–4). Also, there are a presence, albeit in low percentages (< 10%), of Bitectatodinium tepikiense and Spiniferites elongatus. In accordance to the available literature, especially concerning the Mediterranean area, the species I. aculeatum and S. mirabilis are considered to represent a warm signal, while the cold assemblages includes the species B. tepikiense, S. elongatus and N. labyrinthus (e.g., Edwards and Andrle, 1992; Harland, 1983; Rochon et al., 1999; Taragona i Pujolà, 1997; Turon and Londeix, 1988; Zonneveld, 1996). O. centrocarpum is not included in our interpretation because it is a cosmopolitan species found in modern sediments in a broad range of environmental conditions (e.g. Marret and Zonneveld, 2003; Mudie, 1992; Rochon et al., 1999; Turon, 1984; Wall et al., 1977).

Oxygen isotope (δ18O) obtained from Globigerina bulloides and relative abundance of main species of dinocysts (%) and their concentration in the core MD04-2797CQ (Sicilian-Tunisian Strait) during the last glacial-interglacial transition and the Early Holocene. Main thermophilous species of dinocysts are S. mirabilis and I. aculeatum. Grey bands indicate Heinrich events (H1) and the Younger Dryas event.

Valeurs d’oxygène isotopique (δ18O) obtenues à partir de Globigerina bulloides et abondance relative des principales espèces de dinokystes (%) et leur concentration dans la carotte MD04-2797 CQ (détroit entre Sicile et Tunisie), pendant la dernière transition glaciaire-interglaciaire et l’Holocène inférieur. Les principales espèces thermophiles de dinokystes sont Spiniferites mirabilis et Impagidinium aculeatum. Les bandes grises indiquent les évènements de Heinrich (H1) et celui du Dryas récent.

Oxygen isotope (δ18O) obtained from Globigerina bulloides and relative abundance of main species of dinocysts (%) and their concentration in the core MD95-2043 (Alboran Sea) during the last glacial-interglacial transition and the Early Holocene. Main thermophilous species of dinocysts are S. mirabilis and I. aculeatum. Grey bands indicate Heinrich events (H1) and the Younger Dryas event.

Valeurs d’oxygène isotopique (δ18O) obtenues à partir de Globigerina bulloides et abondance relative des principales espèces de dinokystes (%) et leur concentration dans la carotte MD95-2043 (Mer d’Alboran) pendant la dernière transition glaciaire-interglaciaire et le Dryas récent. Les principales espèces thermophiles de dinokystes sont Spiniferites mirabilis et Impagidinium aculeatum. Les bandes grises indiquent les évènements de Heinrich et celui du Dryas récent.

Oxygen isotope (δ18O) obtained from Globigerina bulloides and relative abundance of main species of dinocysts (%) and their concentration in the core MD99-2346 (Gulf of Lions) during the last glacial-interglacial transition and the Early Holocene. Main thermophilous species of dinocysts are S. mirabilis and I. aculeatum. Grey bands indicate Heinrich events (H1) and the Younger Dryas event.

Valeurs d’oxygène isotopique (δ18O) obtenues à partir de Globigerina bulloides et abondance relative des principales espèces de dinokystes (%) et leur concentration dans la carotte MD99-2346 (Golfe du Lion) pendant la dernière transition glaciaire-interglaciaire et l’Holocène inférieur. Les principales espèces thermophiles de dinokystes sont Spiniferites mirabilis et Impagidinium aculeatum. Les bandes grises indiquent les évènements de Heinrich (H1) et celui du Dryas récent.

4.1.1 Thermophilous species

S. mirabilis prefers sea-surface temperature between 10 and 15 °C during winter and 15 to 22 °C during summer (Rochon et al., 1999). Morzadek-Kerfourn (1998) demonstrated its southward tropical extension (as far as 10°N). The dominance of this thermophilous species (Harland, 1983; Marret and Turon, 1994; Rochon et al., 1999; Turon, 1981b, 1984) allows us to define warm periods. In our records (3 cores), we have identified a significant increase (20–40%) of this taxa during the Bölling/Alleröd interval and at the beginning of the Holocene.

In addition to S. mirabilis, the subtropical species I. aculeatum occurred also during these warm intervals. The maximum frequencies of this latest species and most Impagidinium species (except I. pallidum) are in tropical to warm temperate waters between 20 and 35°N (Harland, 1983). I. aculeatum, which is typical of subtropical domains (Turon, 1984), marks also warm episodes as well as the Bölling/Alleröd and the Early Holocene. In this study, I. aculeatum does not reach 10% during the Bölling/Alleröd but increases to 30% at the beginning of the Holocene.

4.1.2 Cryophilous species

N. labyrinthus is a typical oceanic species. It has been positively correlated with open cold water masses and high (winter) nutrient availability (Devillers and de Vernal, 2000; Harland, 1983; Turon and Londeix, 1988). Its main published distribution, so far, is between 45 and 65°N in the North Atlantic Ocean (de Vernal et al., 2005; Matthiessen, 1995; Rochon et al., 1999), especially on the southwestern Iceland margin where the Irminger Current dominates (Marret et al., 2004). In our records (Figs. 2–4), we have identified a significant increase of the percentage of this species during the Younger Dryas interval (35–70%). It is clear that this taxa tends to mark the transition between glacial and interglacial conditions. This finding confirms the suggestion of Turon (1984) and Eynaud et al. (2004), concerning the transitional character of N. labyrinthus during events of severe hydrological changes.

B. tepikiense is mainly distributed from temperate to sub-Arctic environments of the North Atlantic (55 and 65°N), with maximum representation south of the Gulf of St. Lawrence (de Vernal et al., 2001; Rochon et al., 1999). This species appears to tolerate large seasonal variations in temperature, with cold winters (as cold as 1 °C) and mean summer temperatures over 15 °C (de Vernal et al., 2005). In our records, B. tepikiense is scarce or in very low percentages as well as S. elongatus. This latest species occurs frequently in sediments of Baffin Bay and of the Barents Sea and occurs in significant numbers in the central North Atlantic between 50 and 60°N (Rochon et al., 1999). In this study, the percentages of these two species do not reach 10% and they are nearly absent during the Early Holocene. The lower percentages of B. tepikiense and S. elongatus obtained at the end of Heinrich Event 1 and especially during the Younger Dryas in all our records are probably linked to the coeval presence of N. labyrinthus.

4.2 Dinocyst concentration

Dinocysts are abundant throughout all the studied cores (Figs. 2–4), with cell concentrations varying between 1000 and 10,000 cysts/cm3. In this study, we have identified a major peak of dinocyst concentrations (8000–10,000 cysts/cm3) during the Younger Dryas. Also, the optimal development of N. labyrinthus during the Younger Dryas coincides with the maximum dinocyst concentration in all studied sites (Rouis-Zargouni, 2010). The occurrence of this species in high percentage is currently associated to cold water masses with high nutrients availability (Devillers and de Vernal, 2000; Turon and Londeix, 1988). These observations suggest an increase of nutrients availability in the western Mediterranean Sea as well as in the Iberian margin (Eynaud, 1999) during this cold event.

5 Discussion

As well as in the North Atlantic region, the last deglaciation in the Mediterranean Sea is also punctuated by abrupt climate changes and we distinguished warm and cold intervals:

5.1 The warm intervals of the last deglaciation

The beginning of the Bölling/Alleröd, dated at about 14.8 ka cal. BP (Rasmussen et al., 2006; Wolff et al., 2010), is marked by the development of the warm water species I. aculeatum (10%) and especially S. mirabilis (15–20%) in the western Mediterranean Sea. The proliferation of these species correspond to the sudden warming of the sea-surface temperatures which increased from 9 °C during the last glacial period to 16 °C during the Bölling/Alleröd (Essallemi et al., 2007; Kallel et al., 1997a; Melki et al., 2009; Rouis-Zargouni et al., 2010; Sbaffi et al., 2004). So, it is rather surprising to find B. tepikiense, characteristic of the coldest phases of the last glacial period (Turon and Londeix, 1988; Turon et al., 2003), in the Adriatic Sea during the Bölling/Alleröd (Combourieu-Nebout et al., 1998). The high seasonal thermal contrast of this species allows us to suggest an increase run-off of cold fresh water from the Pô river. This situation was due to the increase of precipitation and atmospheric temperature which induced snow melting in the Borderland Mountains (Combourieu-Nebout et al., 1998).

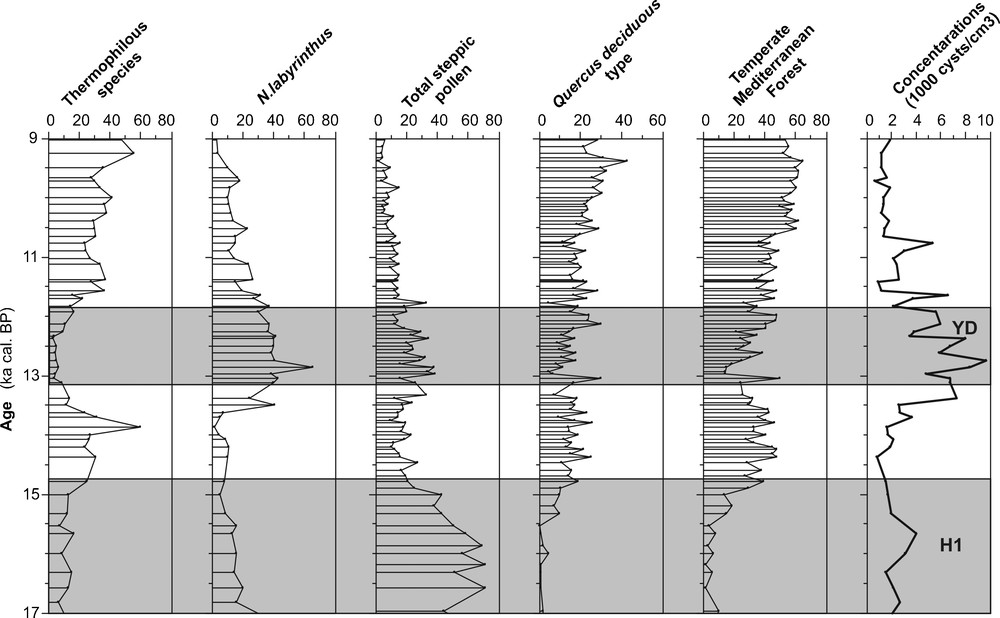

In addition, the pollen records show a contraction of Artemisia-rich steppe areas and well-developed forest vegetation during the Bölling/Alleröd in the Alboran sea (Fig. 5: Fletcher and Sanchez-Goni, 2008; Fletcher et al., 2009), in the Adriatic sea (Combourieu-Nebout et al., 1998; Guinta et al., 2003) and in the Iberian margins hinterland (Fletcher et al., 2007). These observations confirm that the Bölling/Alleröd is warm and wet in the Mediterranean Sea.

Relative abundance (%) of N. labyrinthus and thermophilous species of dinocysts (S. mirabilis and I. aculeatum) in addition to the percentages of pollen records (from Fletcher et al., 2009) and their concentrations in the core MD95-2043 (Alboran Sea) during the last glacial-interglacial transition and the Early Holocene. Grey bands indicate Heinrich events (H1) and the Younger Dryas event.

Abondance relative (%) de Nematosphaeropsis labyrinthus et des espèces de dinocystes (Spiniferites mirabilis et Impagidinium aculeatum) ajoutée aux pourcentages d’enregistrements de pollen (d’après Fletcher et al., 2009) et leurs concentrations dans la carotte MD95-2043 (Mer d’Alboran) pendant la dernière transition glaciaire-interglaciaire et l’Holocène inférieur. Les bandes grises indiquent les évènements de Heinrich (H1) et celui du Dryas récent.

At about 12.8 ka cal. BP, the warm dinocysts taxa decrease considerably and after a millennium reappear at the beginning of the Holocene (11.7 ka cal. BP). These maximum values ever obtained for S. mirabilis during the last deglaciation of the Mediterranean Sea enable us to locate the warmest period as the Holocene and the Bölling/Alleröd. Also, in the Bay of Biscay, the beginning of the Holocene has been clearly identified with elevated percentages of S. mirabilis (Zaragosi et al., 2001). In temperate domains of the Atlantic (Iberian Margin, Sanchez-Goni et al., 1999; Rockall Margin, Eynaud, 1999) as well as further north in the South Icelandic Basin (Eynaud et al., 2004), the warmest substage of MIS 5 was characterised by a significant increase of S. mirabilis. The same observation was made during MIS 7 and MIS 5 in the Bay of Biscay (Penaud et al., 2008).

5.2 The cold interval of the last deglaciation

The cold events of the last deglaciation are marked by the development of N. labyrinthus and the subpolar species B. tepikiense and S. elongatus especially at the end of Heinrich Event 1 (H1). These latest species with Neogloboquadrina pachyderma (left coiling) are characteristic of the Heinrich events in the Mediterranean Sea (Rouis-Zargouni, 2010; Rouis-Zargouni et al., 2010) and in the Iberian Margin (Turon et al., 2003). So, they are scarce or absent during the Younger Dryas in the western Mediterranean Sea. In contrast, N. labyrinthus shows its optimum during this brief cold event. In addition, pollen records show a development of the Artemisia-rich steppe in the Adriatic Sea (Combourieu-Nebout et al., 1998; Guinta et al., 2003), Alboran Sea (Combourieu-Nebout et al., 1999, 2002; Fletcher and Sanchez-Goni, 2008) and Iberian margin (Sanchez-Goni et al., 2002; Turon et al., 2003) areas during the Younger Dryas and the Heinrich events. These simultaneous responses of the vegetation and our microfloral records confirm that at about 12.8 ka cal. BP, a return to dry and cold climate is recorded in the Mediterranean Sea and along the neighbouring borderlands of this sea as well as during the Heinrich events. So, we observe a persistence of the pollen of temperate Mediterranean forest (TMF: namely Acer, Alnus, Betula, Corylus, Fraxinus excelsior type, Populus, Taxus, Ulmus, Quercus deciduous type, Quercus evergreen type, Quercus suber type, Cistus, Coriaria myrtifolia, Olea, Phillyrea and Pistacia) with a lower increase of the Artemisia-rich steppe during the Younger Dryas than during the Heinrich events (Fig. 5). These observations suggest that the Younger Dryas is less dry and cold than the Heinrich events. Also, the sea-surface temperatures (based on planktonic foraminifera) of this period, which are about 10 °C, in the Tyrrhenian sea (Kallel et al., 1997b; Sbaffi et al., 2004), in the Gulf of Lions (Melki et al., 2009), in the Alboran sea (Cacho et al., 1999) and in the Sicilian-Tunisian Strait (Essallemi et al., 2007; Rouis-Zargouni et al., 2010) are higher than those recorded during the Heinrich events (about 1 to 2 °C).

5.3 Ecological information provided by Nematosphaeropsis labyrinthus

In modern western Mediterranean sediments, the percentage of N. labyrinthus does not reach 20% (Mangin, 2002). So, during the Younger Dryas, the percentages of this taxa increase considerably in all studied domains (Figs. 2–4). During this cold event, its distribution shows a gradual increase from the south to the north of the Mediterranean Sea. In fact, N. labyrinthus constitutes 40% of the dinocyst assemblage in the Sicilian-Tunisian Strait, 50% in Alboran Sea but the highest percentage (90%) occurred in the Gulf of Lions. Also, Eynaud (1999) has shown an important development of this species in the Iberian margin but the percentages remains less significant than those recorded in the western Mediterranean Sea. So, the highest percentage of this taxa in the Gulf of Lions appears related to the coldest condition in this site in comparison to the other regions of the Mediterranean. The Gulf of Lions is dominated by strong continental winds (the Mistral and the Tramontane), which generate up-wellings (Millot, 1982) and down-wellings (Millot, 1990) leading to the formation of the WMDW. The dry and cold climate of the Younger Dryas could cause an intensification of the thermohaline circulation and the acceleration of the subsurface MOW. This hypothesis is confirmed by the presence of ‘coarse-grained contourites’ in the gulf of Cadix (west of Gibraltar strait) during this cold event (Toucane et al., 2007). This situation facilitates the vertical mixing of the water column and cause increased advection of nutrients into the euphotic layer where they can be used for phytoplankton production.

In addition, the optimum occurrence of N. labyrinthus during the Younger Dryas is contemporaneous to the maximum concentration of dinocysts in the western Mediterranean Sea. Also, this species has been positively correlated with open cold water masses and high (winter) nutrient availability (Devillers and de Vernal, 2000; Harland, 1983; Turon and Londeix, 1988). These observations lead us to conclude that the highest abundance of N. labyrinthus in association with the maximum concentration of dinocysts represents an important signal of nutrients availability.

In the Atlantic Ocean and, particularly, on the northern part of the Mediterranean Sea, in the Bay of Biscay, N. labyrinthus occurs in this region during the Bölling/Alleröd. However, a development of Pentapharsodinium dalei is recorded during the Younger Dryas in the same site (Eynaud, 1999). In the West of Scotland, this same cold event is characterised by the presence of Islandinium minutum (Boessenkool, 2001). This species, absent also in the Bay of Biscay, is correlated to the development of seasonal sea ice cover. These observations reflect more drastic conditions during the Younger Dryas in the Atlantic Ocean than in the Mediterranean Sea. In conclusion, the Mediterranean and Iberian margins microfloral associations during the Younger Dryas are equivalent to those of the Bölling/Alleröd in the Bay of Biscay. In addition, N. labyrinthus has characterised the transition between the marine isotopic substages7e/7d in the North of the Bay of Biscay (Penaud et al., 2008). Also, Turon (1984) and Eynaud et al. (2004) have suggested the transitional character of this species during the events of severe hydrologic changes. Therefore, it appears obvious that N. labyrinthus may be considered as a significant ecostratigraphic proxy for periods of severe climatic changes, but its necessary to document the past distribution of this species carefully in relation with the geographic studied field.

6 Conclusion

Dinocyst records confirm the existence of climatic instability during the last glacial-interglacial transition in the western Mediterranean Sea. The development of the warm dinocyst species during the Bölling/Alleröd and the Early Holocene reflects a comparable warming condition during these two periods. The cooling of the Younger Dryas interrupts abruptly this climatic amelioration and leads to the proliferation of the dinocyst N. labyrinthus.

The highest abundance of N. labyrinthus in association with the maximum concentration of dinocysts could represent an important signal of nutrients availability during the Younger Dryas in the western Mediterranean. Also, the maximum occurrence of this species during this brief cold event may be a useful ecostratigraphic proxy for recognising the events of severe hydrologic changes as the Younger Dryas in the western Mediterranean Sea and in the Iberian margin. However, this propriety must be used in the Atlantic Ocean with caution because of the ecological changes due to environmental variations of the study areas.

The dry and cold climate in the Mediterranean Sea during the Younger Dryas (Beaudouin et al., 2005; Combourieu-Nebout et al., 1999; Triat-Laval, 1978) generates the vertical convection of the water column and leads to the intensification of the formation of WMDW, in the Gulf of Lions. This condition intensifies the thermohaline circulation and the exchange of water masses between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. This hypothesis must be further developed by the study of benthic foraminifera and ostracods, which reflect the physical and chemical proprieties of the deep circulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Institut National des Sciences de l’Univers (INSU) of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the RV Marion-Dufresne officers and crew, the IMAGES program and the Institut Paul-Emile-Victor (IPEV) for support and organisation of the coring cruises (GINNA, GEOSCIENCES, PRIVILEGE). We would finally like to thank B. Lecoat for isotope analyses and ARTEMIS for the radiocarbon age measurements and M.H. Castera (UMR-EPOC5805) for his technical assistance.