1 The Palaeoproterozoic Francevillian basin (Gabon)

Located in eastern part of Gabon, the Francevillian basin (Fig. 1) is a Palaeoproterozoic basin (about 2 Gyr ago), with low deformation and no metamorphism (Baud, 1954; Bouton et al., 2012; Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986; Gauthier-Lafaye and Weber, 1989, 2003; Thiéblemont et al., 2009; Weber, 1969). The discovery and exploitation of the manganese ore deposits of Moanda (Fig. 1.2; Baud, 1954; Weber, 1969), the presence of the uranium ore deposits of Mikouloungou, Mounana (Des Ligneris and Bernazeaud, 1964) and of the natural fission reactors (Bodu et al., 1972; Neuilly et al., 1972) of Bangombé, Okelobondo and Okelonéné, so-called Oklo (Fig. 1.2), allowed an accurate reconstruction of basin geometry and filling using mapping, outcrop description and well logging.

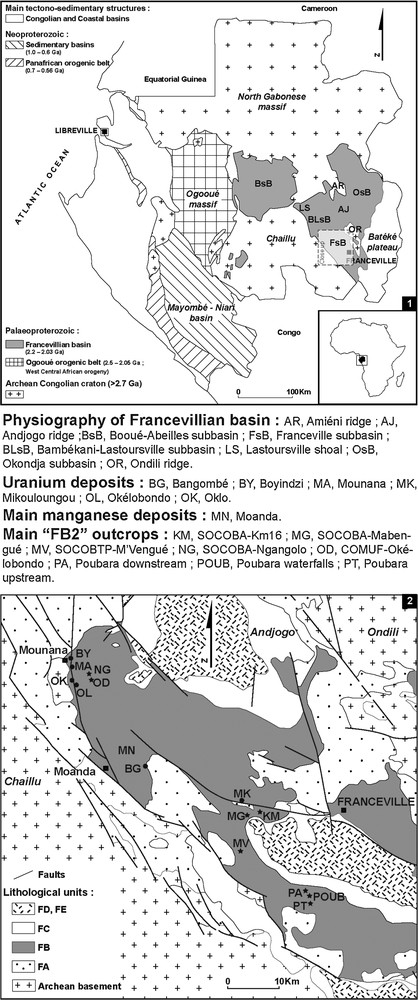

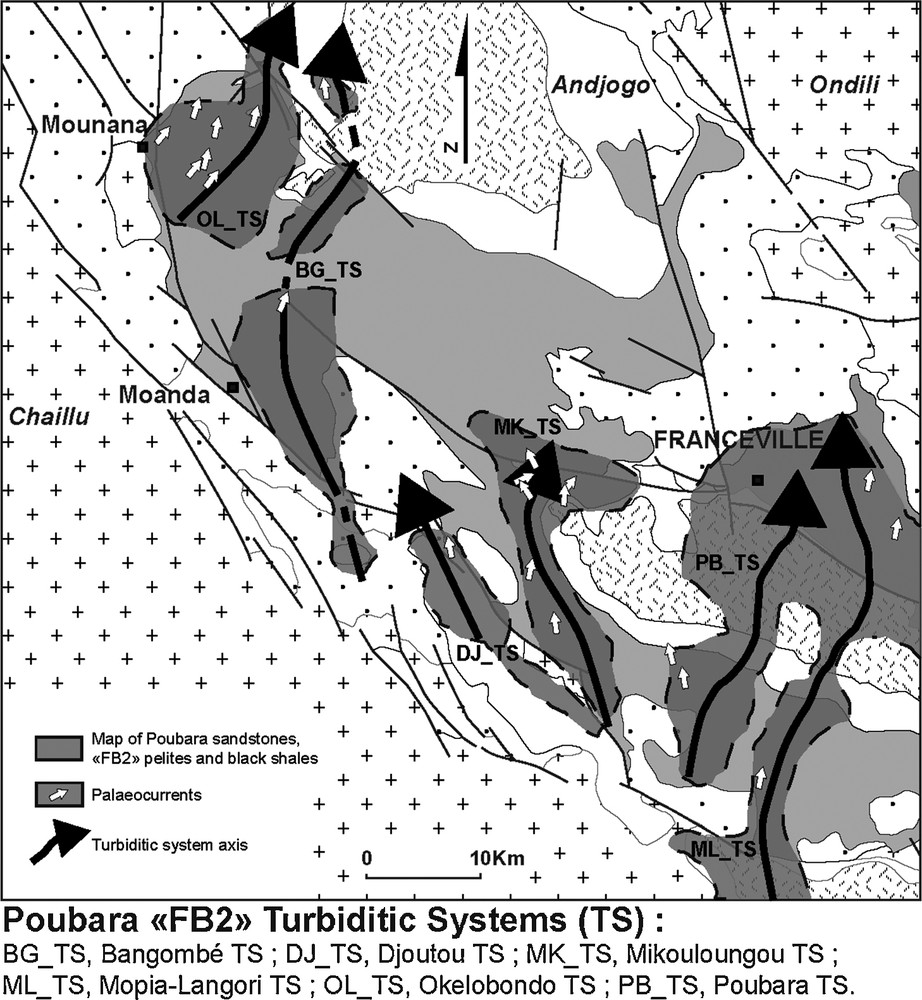

The studied area in the Francevillian basin setting (Palaeoproterozoic, Gabon): 1.1: main tectono-sedimentary units from Feybesse et al. (1998). Typology of main sub-basins, shoals and ridges according Weber (1969) and Gauthier-Lafaye (1986) and location of studied area on the southwestern margin of the basin; 1.2: detailed map of Franceville sub-basin and location of the Poubara sandstones main sections and outcrops. Lithological Francevillian units according to Weber (1969) and their cartography in Franceville sub-basin (AREVA, COGEMA, COMUF unpublished data; Thiéblemont et al., 2010; Weber, 1969) and uranium deposits location from Des Ligneris and Bernazeaud (1964), Gauthier-Lafaye (1986) and Weber (1969).

Le secteur étudié : 1.1 : le Bassin francevillien (d’après Feybesse et al., 1998) et ses principaux éléments physiographiques (Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986 ; Weber, 1969) ; 1.2 : le sous-bassin de Franceville : les données cartographiques (AREVA, COGEMA, COMUF, inédits ; Thiéblemont et al., 2010 ; Weber, 1969) et les gisements d’uranium (Des Ligneris et Bernazeaud, 1964 ; Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986 ; Weber, 1969).

The Francevillian basin (Fig. 1.1) is subdivided into four sub-basins (sB): Booué sB, Bambékani-Lastoursville sB, Okondja sB and Franceville sB, separated by shoals or ridges linked to horsts: Amiéni, Andjogo, Ondili, and Lastoursville (Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986; Thiéblemont et al., 2009; Weber, 1969). The classical lithostratigraphic Francevillian succession includes five units from FA to FE (Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986; Weber, 1969) showing a fining-upward trend, corresponding to a widespread sequence of basin-filling. Sedimentological studies provided an interpretation of the depositional environment of FA (Haubensack, in Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986) and FB (Azziley-Azzibrouck, 1986; Ossa-Ossa, 2010; Pambo et al., 2006). The discovery of pyritized fossils, interpreted as large colonial organisms (El Albani et al., 2010), in the upper FB, shows that the Francevillian basin combines excellent preservation of 2-Gyr-old sediments, with the first appearance of colonial organisms on Earth. The presence of natural fission reactors hosted in the basin is also unique in the world.

The recent exploration of this basin by AREVA induced fieldwork in 2009 and 2010 to update the Francevillian basin deposits, using recent concepts in basin analysis and sedimentology. The new observations examine all the series from FA to FE, and are spread largely over the southwestern part of the Francevillian basin. They include drilled cores, core logging, and study of clean outcrops (rivers, quarries, cliffs, roadside cuts) or saprolitised outcrops. Note that saprolites differ from laterites because they sometimes keep the texture and the structure of the original rock (structured saprolites) that can be interpreted.

This paper presents the new results on the sedimentology and facies analysis of the upper part of FB or FB2 (Weber, 1969) and the resulting hydrodynamic and palaeoenvironment interpretations.

2 The Poubara sandstones and related shales in Francevillian series

FB2 consists of the conformable superposition of the Poubara sandstones, sensu FB2a, and banded black shales and shales, sensu FB2b (Ossa-Ossa, 2010; Pambo et al., 2006; Weber, 1969). The Poubara sandstones have only been identified in Franceville sB and Bambékani-Lastoursville sB (Fig. 1.1). The Moulendé fossiliferous levels have been described at the base of the black shales in FB2b (El Albani et al., 2010; Ossa-Ossa, 2010).

2.1 The lithostratigraphic succession in Francevillian basin: state of the art

The Francevillian series unconformably overly Archean shield units. The filling has been divided into five lithologies (FA to FE) with no hiatuses (Weber, 1969). The total thickness is 1,000–4,000 m thick (Gauthier-Lafaye and Weber, 2003), or less than 2,000 m thick (Ossa-Ossa, 2010). Sedimentation of FA (100 to 1000 m thick) and FB (400 to 1000 m thick) records the differential subsidence of the basin that formed the four sub-basins (Fig. 1.1). Sedimentation of FC (10 to 40 m thick, exceptionally 150 m) is assumed to represent the end of the FA–FB cycle and defines a datum plane (Gauthier-Lafaye and Weber, 2003; Préat et al., 2011; Thiéblemont et al., 2009; Weber, 1969). Sedimentation of FD and FE (up to 1000 m thick) corresponds to a new depositional cycle in Okondja sB; high subsidence is linked to a larger wavelength at the scale of the whole Francevillian basin (Feybesse et al., 1998).

FA corresponds to a coarse-grained (including conglomerate) siliciclastic series that is usually poorly graded, and mainly consists of quartz grains, cemented by illite and formed by the stacking of 2D and 3D dunes, interbedded with thinner pelitic levels (Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986). The depositional environment is interpreted as a braided fluvial complex (Gauthier-Lafaye and Weber, 2003). Upper FA that hosts the uranium-bearing ore deposits (Des Ligneris and Bernazeaud, 1964) corresponds to medium to coarse sandstone interbedded with pelites with a good to pretty good grading. Sedimentary structures suggest a tide-related environment (Deynoux and Duringer, in Gauthier-Lafaye and Weber, 1989, 2003). The whole FA was previously interpreted as a deltaic environment (Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986; Pambo et al., 2006).

The transition FA–FB corresponds to a collapse of the Francevillian basin related to the tectonic subsidence of the sub-basins up to 800 m deep (Bouton et al., 2012; Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986; Gauthier-Lafaye and Weber, 1989, 2003; Weber, 1969), associated with an increase in the organic matter (OM) content in sediments (deposition of FB black shales: Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986). At the southwestern edge of the Franceville sB and in Okondja sB, olistolithes, polygenetic breccias record this tectonic activity (Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986). They are correlated to distal mudflow deposits and fine-grained turbidites (Azziley-Azzibrouck, 1986). The transition FA–FB is interpreted as a marine transgression and the FB siliciclastic sediments progressively fill the Francevillian basin (Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986; Préat et al., 2011; Thiéblemont et al., 2009; Weber, 1969), forming a slight unconformity over the FA formation (Gauthier-Lafaye and Weber, 1989). The black shale series FB is divided in its lower part, by interstratified megaconglomeratic levels (Oklo breccia and sandstones, FB1a) or in its upper part by massive sandstone with rare sedimentary structures (Poubara sandstones, FB2a) (Weber, 1969). The Poubara sandstones correspond to Middle Francevillian (Baud, 1954) and allow the black shales FB1b and FB2b to be distinguished. The transition FB1b–FB2a is poorly documented. The succession FA–FB has been recently interpreted as a deltaic environment (Ossa-Ossa, 2010) in continuity with the FA delta (Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986).

According to Weber (1969), the FC series correspond to a dolomitic formation with stromatolites and cherty levels which spill over the basin edges and spread over the Archean basement. They are used to separate the black shales and pelites FB and FD: in the locations where the Poubara sandstones and cherts FC are missing, the pelites and black shales units can be hard to identify. In the Okondja sB, FD and FE record the increase of a volcaniclastic fraction in the sedimentary filling (Gauthier-Lafaye and Weber, 2003; Weber, 1969).

2.2 The Poubara sandstones (FB2a) and the black shales (FB2b): state of the art

The Poubara sandstones were defined near the village of Poubara where the Ogooué River shows spectacular waterfalls (Fig. 1.2). They form a remarkable cuesta in the Franceville sB. The Poubara sandstones are blue-grey to black, fine-grained, isogranular quartz sandstones with rare feldspars and micas. Beds are massive with no internal stratification or grading, reaching sometimes several metres in thickness (Weber, 1969). This formation is 50–100 m thick and can reach 150 m. It can also thin and disappear in FB black shales. Good outcrops are rare and excavations for construction or mining provide high-quality outcrops (Fig. 1.2).

All previous interpretations are consistent with a progressive and continuous filling of the Francevillian basin (Weber, 1969), suggesting a shallow-water environment for Poubara sandstones deposition. Despite excellent outcrops, there is still a debate concerning the depositional environment, the hydrodynamic conditions and the source of the Poubara sandstones. Three models have been proposed:

- • a tempestite (HCS, hummocky cross stratification-dominated) model (Azziley-Azzibrouck, 1986; Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986; Pambo et al., 2006) with cordons oriented WNW–ESE;

- • a tide-dominated delta model (El Albani et al., 2010; Ossa-Ossa, 2010) with a flood direction towards the south-west;

- • a combined shelfal turbidites-tempestites model (Thiéblemont et al., 2009) with a supply from south-west.

The lateral facies transition of sandstones to shales and black shales has been less studied than the sandstones themselves. Recent work (El Albani et al., 2010; Ossa-Ossa, 2010) interpret black shales as distal forebeach or offshore deposits with interbedding of sandstone beds with HCS. According to these authors, black shales FB2b represent distal deposits of delta FA–FB, i.e. a transgressive prodelta.

3 The analysis of the Poubara sandstones and associated pelites

The several hectometre-long outcrops resulting from the excavations of the new hydroelectric power plant of Poubara (Fig. 1.2) showed that black shales, pelites and the Poubara sandstones can constitute a homogeneous formation or be associated to form organized alternations of fining-up and thinning-up facies associations. We are going to describe these main facies associations.

3.1 The Poubara facies (PF) associations

The field work allowed nine facies to be recognised in the FB2 part of the Francevillian series: two facies for black shales and pelites, two for sandstones and five for the Poubara sandstones sensu stricto.

3.1.1 PF1 – Homolithic, finely-laminated, tabular muddy facies

Well exposed in Franceville (Fig. 1), facies PF1 corresponds to fissile to platy pelites. It can constitute several tens-of-metres-thick intervals. Two sub-facies have been defined according to their OM and silt contents (Azziley-Azzibrouck, 1986; Weber, 1969):

- • PF1.1 – black shales facies. Facies PF1.1 corresponds to black shales (1–5% Total Organic Carbon, TOC) (Cortial, in Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986; Ossa-Ossa, 2010). Its transition to other coarser facies is sharp (Azziley-Azzibrouck, 1986). It contains numerous fossiliferous levels at the top of the Poubara sandstones (El Albani et al., 2010; Ossa-Ossa, 2010: KM quarry, Fig. 1.2);

- • PF1.2 – pelites and shales facies. Facies PF1.2 is dominated by a silt fraction. The TOC is about 0.5%, and always lower than 1% (Cortial, in Gauthier-Lafaye, 1986), providing a grey to light grey colour. It shows fine to very fine horizontal planar laminations. Its transition to the darker facies PF1.1 is progressive (Azziley-Azzibrouck, 1986).

Facies PF1 corresponds to particle fall-out in a very low-energy depositional environment: facies PF1.1, permanent particle fall-out in the water column and facies PF1.2, the distal part of base cut-out (Tde) of Bouma sequences (1962) or facies F9 of Mutti (1992) or mud turbidites of Piper and Stow (1991).

3.1.2 PF2 – Heterolithic tabular silty-sand facies

This facies PF2 is composed of alternating mudstone (PF1) and very fine- to coarse-grained sandstones with a sand/shale ratio between 5 and 25. The grain size PF2 varies from silts or very fine sandstones (PF2.1) to medium to coarse sandstones (PF2.3) organised in thin to moderately-thick beds. Three sub-facies can be distinguished according to the development of facies Tb, Tc and Td sensu Bouma (1962):

- • PF2.1 – fine-grained turbidites (Tcde). Facies PF2.1 is composed of centimetre- to several centimetre-thick beds. The base of the beds is made of fine or very fine sandstones, with planar horizontal laminations and ripples grading up to siltstone and mudstone. They are commonly found in heterolithic intervals;

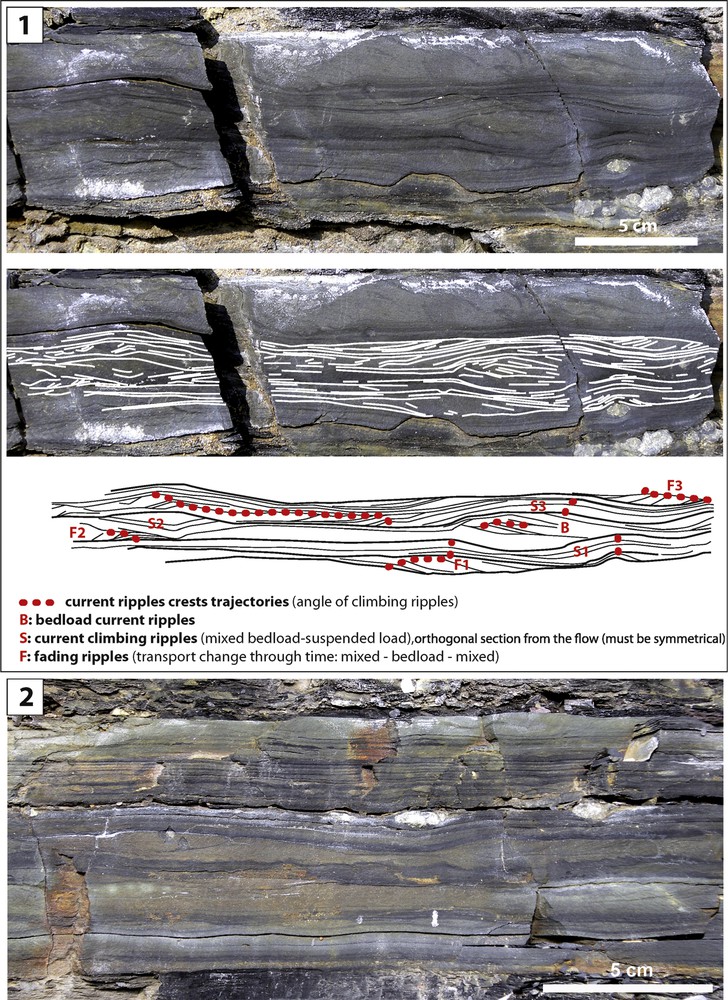

- • PF2.2 – base and top-missing (Tbcd) Bouma sequences. Facies PF2.2 (Fig. 2) is composed of several centimetre- to decimetre-thick fining-up beds made of very fine to medium sand. These beds are most of time stacked-up to form 15-cm-thick layers. Horizontal or wavy, planar laminations are covered by climbing laminations and ripples (sensu fading ripples according to Piper and Stow, 1991); convolute bedding can occur. The base and top of these composite beds are both sharp; centimetre-scale load structures suggest fast deposition. Facies PF2.2 can grade-up to PF2.1 facies;

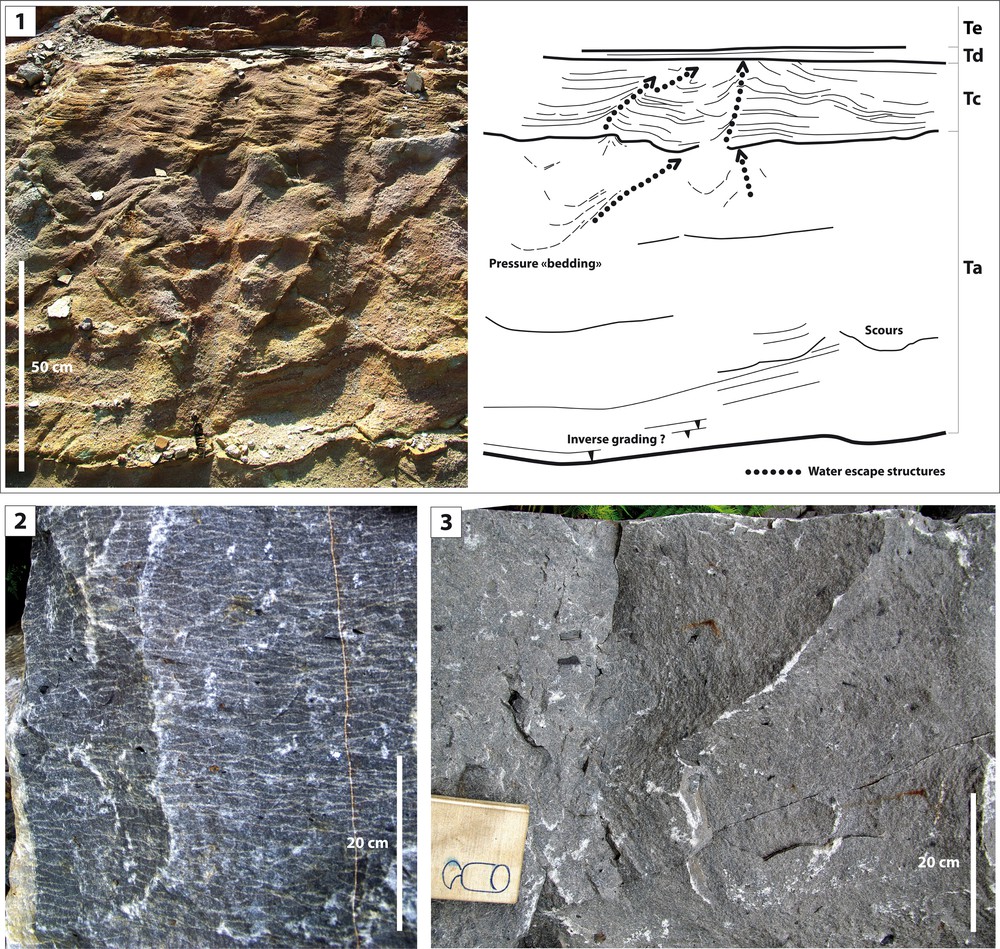

- • PF2.3 – top-missing (Ta) Bouma sequences. Facies PF2.3 is made of massive, medium to coarse sandstone (Fig. 3.1). Bed thickness varies from one to a few decimetres, up to one metre in some cases. Planar laminations are rare and crude. Silty beds can be interbedded. The upper sharp grain-size boundary suggests by-passing.

Fine-grained turbidites: 2.1: facies PF2.2: amalgamation of Tc and Tcd Bouma sequences, characterized by a cyclic change of transport from unidirectional bedload (current ripples) to mixed bedload-suspended load (climbing current ripples) in lower flow regime conditions. The outcrop is roughly orthogonal to the flow (with a mean variation of at least ± 60°): this leads to the formation of symmetrical structures (see Harms et al., 1975 or Allen, 1982 for more details), which can be mistaken for wave ripples. Lamina set S3 is a case example with symmetrical ripples that laterally pass into climbing and bedload current ripples (fading ripples according to Piper and Stow, 1991); 2.2: facies PF2.2: amalgamation of Tc and Tcd Bouma sequences. This bed is more or less at right angle from the previous one, and then parallel to the flow. This bed shows clear evidence of only unidirectional flow in the lower flow regime (current ripples). The transport mode changed from bedload (dominant) to mixed bedload-suspended load (climbing ripples). Palaeoflow to NNE. These examples come from SOCOBA–KM16 quarry (KM).

Turbidites tronquées à la base de type Tc et Tcd de Bouma (1962) : 2.1 : faciès PF2.2 : association de rides de courant et de rides chevauchantes en vue subperpendiculaire à l’écoulement, pouvant donner des morphologies symétriques, à ne pas confondre avec des rides de vagues ; 2.2 : faciès PF2.2 : selon une vue parallèle à l’écoulement mettant bien en évidence l’unidirectionnalité de l’écoulement (vers NNE). Carrière SOCOBA–Km16 (KM), secteur de Moulendé.

Coarse-grained turbidites: 3.1: facies PF2.3: Tacd Bouma sequences (PA excavations of new hydraulic plant, Poubara). This sequence is intermediate between a Lowe sequence (Ta) and a Bouma sequence. It means that the associated flow changed from a concentrated density to a turbidity flow (Mulder and Alexander, 2001). The Lowe sequence is characterized by coarse-grained sands, with possible inverse grading at the base, numerous scours and water escape structures; 3.2: facies PF4.1: dish and pillar, water escape structures: fluidized flow deposit; 3.3: facies PF4.2: Coarse-grained sandstones with siltstones containing angular pebbles (matrix-supported conglomerate): debris flow deposit. These last two examples come from SOCOBA-Ngangolo quarry (NG), in Mounana area. They provide examples of S2 and S3 intervals of coarse-grained turbidites of Lowe (1982). Facies PF4 correspond to facies F5 and F4 (Mutti et al., 1992). It is interpreted as the product of concentrated to hyperconcentrated flow deposits (Mulder and Alexander, 2001).

Turbidites tronquées au sommet : 3.1 : faciès PF2.3 : turbidite Tacd de Bouma (1962) dans les fouilles de la future centrale hydroélectrique de Poubara (PA) ; le terme Ta est une séquence de Lowe (1982), à sables très grossiers, granoclassement inverse, érosion interne et figures d’échappement de fluides ; 3.2 : faciès PF4.1 : empilement de coupelles provoquées par l’expulsion de fluides ; 3.3 : faciès PF4.2 : intraclastes silteux. Ces deux derniers exemples sont situés dans la carrière de la SOCOBA-Ngangolo (NG).

The heterolithic tabular facies PF2 corresponds to different expressions of the classical Bouma sequence (1962) or fine-grained turbidites: from base-missing sequence (PF2.1 facies) to top-missing sequence (PF2.3 facies). Facies PF2.1 is interpreted as the final fall-out deposition of turbulent surges (fine-grained turbidites of Piper and Stow, 1991, or distal part of facies F9 of Mutti et al., 1992). Facies PF2.2 (Fig. 2) corresponds to base cut-out Bouma sequences (Bouma, 1962). It is deposited by mostly turbulent flows (turbidites sensu stricto, Mulder and Alexander, 2001). Facies PF2.3 (Fig. 3.1) corresponds to the Ta unit (Bouma, 1962) or F8 facies (Mutti et al., 1992); it is interpreted as concentrated flow deposits of Mulder and Alexander (2001).

3.1.3 PF3 – Tabular facies and small-size scours

Well exposed in MG and KM quarries (Fig. 1.2), facies PF3 is mainly made of fine to medium sands with medium-scale erosional structures at the bed tops (PF3.1) or bases (PF3.2). Sedimentary structures are crude. It is frequent in the Poubara sandstones where the two sub-facies are interbedded:

- • PF3.1 – heterolithic tabular facies with mud-draped scours. Facies PF3.1 shows 20- to 50-cm-thick beds with tops frequently eroded by numerous mud-draped scours. These scours are metres wide (between 1 to 2 m) and decimetres deep (W/D ratio ∼ 10) with a downstream elongated shape. Their infill corresponds to PF1 facies. The bed base can be lenticular and slightly erosive. These beds constitute metre-thick heterolithic intervals;

- • PF3.2 – homolithic tabular facies with metric scours (scour and fill). This facies shows 0.5- to 1-m-thick beds with irregular bases that locally deeply erode the underlying bed. These beds are fining up (from medium to fine sand). Mud clasts are rare. The elongated scours are frequently 2-m-wide and 0.5-m-deep (W/D ratio ∼4 to 5) with a curved base. These beds are stacked and constitute tabular, several metre-thick sets. Some discontinuous, thin, muddy layers can be interbedded. In dip section, these bed sets look like regular and tabular.

Facies PF3 is characterized by metric scour and fill, megaflute-type; frequency of scouring suggests by-passing. It could be linked to hydraulic jumps in turbidity currents (Mutti and Normark, 1987; Mutti et al., 1992). Facies PF3.1 could correspond to F6 facies of Mutti (1992). These scours are infrequently linked to medium sand lenses with cross-bedding. In some cases, the intense scouring induces sliding or slumping. Facies PF3.2 is interpreted as F7 facies of Mutti (1992) and concentrated flow deposits of Mulder and Alexander (2001).

3.1.4 PF4 – Homolithic, tabular facies and large scours

Facies PF4 is mainly made of medium to very coarse sands (rare granules). Grading and planar laminations are crude and sometimes absent. The beds, up to 3 m thick, constitute 5- to 10-m-thick bed sets. This is the most common facies association in the Poubara sandstones (Fig. 1.2: MV, NG, OD, PA, PT) and is frequently interbedded with facies PF2.3 as in the Poubara area or with facies PF3.2 as in the Mounana area. Sub-facies are characterized according to the presence or absence of numerous large-scale scours and fill structures:

- • PF4.1 – Homolithic, medium to coarse-grained, tabular beds. Facies PF4.1 is made of metre- to several metre-thick beds and can be interbedded with silty levels. It is frequently caped by Tc units of Bouma (1962) frequently mixed by fluid-escape structures. The upper sharp grain size boundary suggests by-passing. Basal pluri-centimetre-thick coarser levels can show traction carpets;

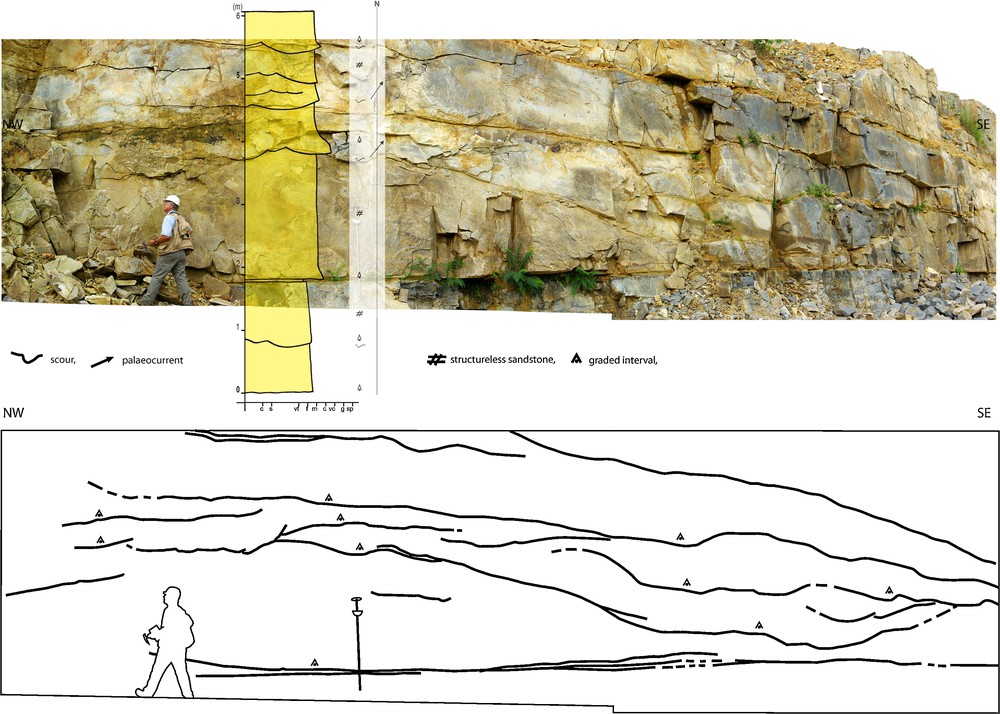

- • PF4.2 – Large scours and fill structures (scour and fill). Facies PF4.2 is made of alternating erosional structures (scouring) and filling by coarse to very coarse sands (Fig. 4). These slightly elongated scours are similar to those described above for PF3.2 facies but are of greater size: about 15 m wide and 2 m deep (W/D ratio ∼ 8). The filling can be completely fluidized (Fig. 3.2). Traction carpets are infrequent. When grading exists, the granules at the base of scouring pass to coarse and medium sandstone. Angular mud clasts are sometimes found (Fig. 3.3).

Facies PF4: large scours and fill, in coarse-grained turbidites. This example comes from SOCOBTP-M’Vengué quarry (MV). †J.-L. Feybesse for scale.

Faciès PF4 : affouillements de grandes dimensions, creusés et remplis par des turbidites grossières à très grossières (scour and fill). †J.-L. Feybesse donnant l’échelle.

Facies PF4 (Figs. 3 and 4) can correspond to high-density or coarse-grained turbidites of Lowe (1982), with well-developed S3 and S2 intervals or facies F5 and F4 (Mutti, 1992). It is interpreted as concentrated to hyperconcentrated flow deposits of Mulder and Alexander (2001).

3.2 The depositional environment of the Poubara sandstones

Our facies analysis allows us to precisely determine the depositional environment of the Poubara sandstones and associated mudstones cropping along the southwestern limit of the Francevillian basin (Fig. 1).

In all the studied outcrops (Fig. 1.2), including excavations in Poubara (PA, POUB, PT), quarries or mining facilities of Franceville area (KM, MG, MV) or in Mounana area (NG, OD), there is no evidence of sedimentary structures indicating a continental shelf depositional environment such as wave ripples, true HCS, sigmoidal cross-bedding or rhythmic mud drapes or couplets. There is no facies deposited above the lower limit of storm action or even fairweather wave action such as HCS (Guillocheau, 1983; Harms in Harms et al., 1975; Guillocheau et al., 2009), symmetrical, 2D ripples (Harms et al., 1975) or 3D polygonal ripples (Guillocheau and Hoffert, 1988; Guillocheau et al., 2009). In shelfal turbidites, the lack of real symmetrical wave ripples is due to high sedimentation rate; however, the low sedimentation rate during FB2 deposition cannot explain this lack. There is also no evidence of tide-influenced deposits (Nio and Yang, 1991; Visser, 1980). The absence of thin, heterolithic alternations or the lack of bi-directional dunes and/or ripples does not allow identification of semi-diurnal and/or equinox tide action. Similarly, there is no evidence of river flood deposits in a coastal submarine environment as HCS, well preserved or deformed in ball-and-pillow structures (Mutti et al., 2007).

All the facies described in the Poubara sandstones and associated muddy deposits are typical of turbidites (Bouma, 1962; Mutti and Normark, 1987; Mutti et al., 1999). They can be interpreted as deposits of fine- to coarse-grained turbidity currents: fine-grained “sequence” (Piper and Stow, 1991): PF2.1 and PF2.2 (Fig. 2); Bouma “sequence”: PF2.3 (Fig. 3.1) and PF3 facies; Lowe “sequence”: PF4 facies (Fig. 3.2, 3.3, 4). The frequency of scouring suggests intense by-passing (PF3 and PF4 facies: Fig. 4). Induced palaeocurrents from ripples, flute or scours indicate a palaeoslope to N010–N040° (Fig. 5). The downslope facies evolution proposed by Mutti (1992) is recognized and shows the longitudinal differentiation of mass flow processes. Facies PF2.1, PF3.1 and PF3.2 correspond to by pass after a decelerating phase allowing deposition of the coarser part of the sediment load. In particular, the graded beds showing rare sedimentary structures and especially asymmetric ripples (HCS-like; discussion Fig. 2) suggest similar facies as those described by Pyles (2009) in the Ross formation. Scouring is also a key component of deep-water turbidite environment, in particular in areas of rapid flow expansion (Macdonald et al., 2011). Isopachous bed architecture suggests mostly deposition in a turbidite lobe setting. Scouring suggests flow spreading at the lobe entrance area.

Spatial distribution of “Poubara” turbidite fans along the southwestern margin of the Francevillian basin and related current directions (Feybesse and Parize, 2011). The map of Poubara sandstones and associated shales and black shales (FB2) is based on an extensive mapping of Poubara sandstones, estimated thickness of FB2 units and facies characterisation from upstream to downstream.

Reconstitution de l’extension spatiale des systèmes turbiditiques de Poubara le long de la bordure sud-occidentale du Bassin francevillien (Feybesse et Parize, 2011).

Along the southwestern edge of the Francevillian basin, the Poubara sandstones essentially correspond to facies association PF4 and more rarely to facies association PF3. The use of mapping data (facies, thickness) and palaeocurrent directions measured at all scales allows a spatial facies distribution to be suggested for the Poubara sandstones and associated pelites and black shales. According to a downslope trend (between to N010° and N040°: Fig. 5), over about 20 to 30 km, the Poubara sandstones show the succession of facies PF4 and PF3, i.e. big scours (Fig. 4) to smaller scours. The scours PF3.1, draped by black shales, are located laterally to homolithic-filled scours PF3.2. The Poubara sandstones pass to tabular heterolithic facies of either PF2 and PF1. The transition of the Poubara sandstones to black shales (PF1.1) is always sharp: for example, in Moulendé (KM: Fig. 1.2), facies PF3.2 is covered with facies PF1.1 in which very fine sandstone PF2.2 is intercalated, these contain the Moulendé colonial organisms’ assemblage (El Albani et al., 2010; Ossa-Ossa, 2010).

4 Discussion and conclusion

The Poubara sandstones are the result of gravitational mass-transport processes dominated by turbidity currents in a marine setting. Most of the observed Poubara sandstones correspond to hyperconcentrated flow deposits (coarse sand to micro-conglomerate), high-density/concentrated flow deposits (supercritical flow of Mutti et al., 1992). The presence of fluid-escape structures, strictly located in coarse hyperconcentrated flow deposits of the Francevillian basin and no evidence of them in the overlying muddy beds, suggest the importance of interstitial fluid in grain transport (Fig. 3.2). The Poubara sandstones have a high sand/mud ratio. With no clear channel fill, the only erosive morphologies correspond to several tenths- to tens-of-metres-long scours, more or less elongated (Fig. 4). The architecture of bed sets and individual beds seems to be larger than that observed on outcrops (100 m to several hundred metres). Deposits thus correspond to laterally extensive draping of sand layers usually observed in lobes. The tabular stacking of beds with metre- to tens-of-metres-scale scours with no channel geometry suggests that deposits are related to hydraulic jumps (Mutti and Normark, 1987) corresponding to the Channel–Lobe Transition Zone (CLTZ of Wynn et al., 2002) or more likely to a lobe entrance because no channel geometry has been observed. Both facies and sedimentary geometry analysis suggest that turbidite deposits forming the Poubara sandstones (facies PF 3 and PF4) are deposited deeper than the lowest limit of storm wave and tide action, i.e. below a water depth of 150 m at the present time, but probably at a larger water depth (200 m) when considering that Palaeoproterozoic storms were more energetic than the present largest storms (Catuneanu and Eriksson, 2007). Such a depositional environment is sufficiently shallow to allow water oxygenation. In addition, oxygenation of water can be increased during turbulent motion of turbidite flows as it has been demonstrated for other ancient depositional environments containing early metazoan faunas (Burgess Shales: Brett et al., 2009).

Turbidity currents are also well known to transport nutrients and even living organism from shallow to deeper water (Emery et al., 1962) and to favour the preservation of soft parts of living remnants by rapid burial (Petrovich, 2001). This new interpretation of the palaeoenvironment of the Moulendé fossiliferous levels would better fit the data, observed in this early period of Earth history. At the sedimentary basin scale, the Poubara sandstones do not record the filling of Francevillian basin and its shallowing-up, but rather suggest a deepening of the basin.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank AREVA Mines Geosciences and Research & Development Directories, the board and colleagues of AREVA Gabon (Franceville), COMUF (Mounana), F. Pambo (COMILOG, Moanda), M. Moussavou (Masuku University, Franceville), V. Cesbron and P. Jeanneret for the help during field work, the managers of SOCOBA and SOCOBTP quarries (Franceville), the drivers who helped us in all our field travels; E. Cheruette and A. Hernandez (Geosciences) for their technical support. We also thank all the colleagues from AREVA, TOTAL, IFP Énergies Nouvelles, Lyon, Poitiers and Masuku Universities, Véolia Environment for their advice and discussions, in particular D. Beaufort, P. Dattilo, S. Ferry, P. Joseph, P. Patrier, J.-L. Rubino, and J.-P. Milesi. Thanks to J. Peakall, F. Gauthier-Lafaye and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the preliminary version of this paper.

According to us, Jean-Louis Feybesse was certainly one of the best “African” geologists. We hope to follow his way of life: humanism/humanity, expertise and sharing. He knew to discern.