1. Introduction

An ophiolitic suite is a sequence of temporally and spatially associated ultramafic, mafic, felsic, and sedimentary rocks interpreted as remnants of subducted oceanic lithosphere. It is often preserved as a suture zone between two continental blocks [Coleman 1977; Dewey 1977; Şengör 1992]. Demonstrably, ophiolite emplacement, or obduction, is a product of the subduction-accretion, arc-continent collision, or continent-continent collision, during which the oceanic lithosphere is incorporated into the continental margin [Dilek and Flower 2003]. The classic ophiolite suites, such as Oman, Cyprus, Xigaze in the Himalayas, and Kızıldağ (SE Turkey), are less common in subduction zones [Wu et al. 2014b]. Ophiolitic mélanges (hereafter referred to as mélanges) represent dismembered ophiolitic sequences with a chaotic mixture of sedimentary and igneous rocks [e.g., Dilek and Furnes 2011; Festa et al. 2010, 2012]. In detail, the mélange is composed of “exotic” blocks, “native or intraformational” blocks, and the sedimentary matrix [Festa et al. 2010]. The exotic blocks consist of siliceous rocks (radiolarite), pillow basalt, mafic and ultramafic rocks like the composition of the ophiolite suites. The native blocks originate from the disruption of a primary lithostratigraphic unit (disrupted brittle layers). The matrix is defined as “deformed” or “fragmented” sandy-muddy rocks which are deformed ductilely relative to the blocks [e.g., Silver and Beutner 1980; Raymond 1984]. During subduction and collision, ophiolitic suites are often dismembered. After undergoing different-scale shearing, they are distributed in a structural belt, parallel to the subduction zone, thus forming a suture zone between the collided continental plates.

In the same suture zone, the ophiolites usually have a relatively uniform age, they record information about a given stage of the oceanic lithosphere preserved in a limited tectonic context [Dilek and Furnes 2011; Festa et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2014b]. In the Alps, the Neo-Tethys Ocean lasted from Middle Jurassic to Eocene, but the Alpine ophiolite only records evolution around 160 Ma [Rosenbaum and Lister 2005; Li et al. 2013, 2015, and references therein]. In the Makran belt, East Iran, the geochronological age of ophiolite is around 115 Ma, but the processes of the accretion are still ongoing [Chu et al. 2020]. Another significant example is the Yarlung Zangbo ophiolite, where the geochronological investigations indicate two peak ages at 120–130 Ma and 155–160 Ma [Chan et al. 2015]. However, the timing of the Neo-Tethys closure is generally considered to be at the beginning of the Paleocene [∼60 Ma; Wu et al. 2014a; An et al. 2021, and references therein]. Age information from ophiolites does not closely reflect the continuous evolution of subducted oceanic plates.

Compared to the ophiolite suite, the mélange may provide more information, since it also includes the materials derived from the overlying plate, and from the subducted oceanic plate with pelagic sedimentary rocks. Therefore, mélanges are ideal objects to understand the evolutionary history of a disappeared ocean and its continental margins [Festa et al. 2010, 2012]. The matrix of a mélange can provide information related to the subduction duration and various provenances of clastic material with multiple compositions [e.g., Coleman 1977]. The study of the ophiolite mélange matrix could broaden our understanding of the process of plate assembling [Li et al. 2021].

Detrital zircon is a useful tool for provenance analysis to rebuild the geological history of sedimentary basins and their surrounding source regions. Ideally, the analysed sample would completely represent geological information of all the possible provenances. Therefore, the age spectra, obtained from a large number of detrital zircon grains, can be used to assess the distribution of source rocks. Therefore, the analysis of detrital zircon age spectra and in situ Hf isotopes might help to improve the understanding of the geological evolution of the source areas by revealing unexpected, or poorly documented, magmatic or metamorphic events [Griffin et al. 2000; Condie et al. 2009]. Such analyses of the deformed and metamorphosed mélange matrix can furthermore help us to restore its evolutional process.

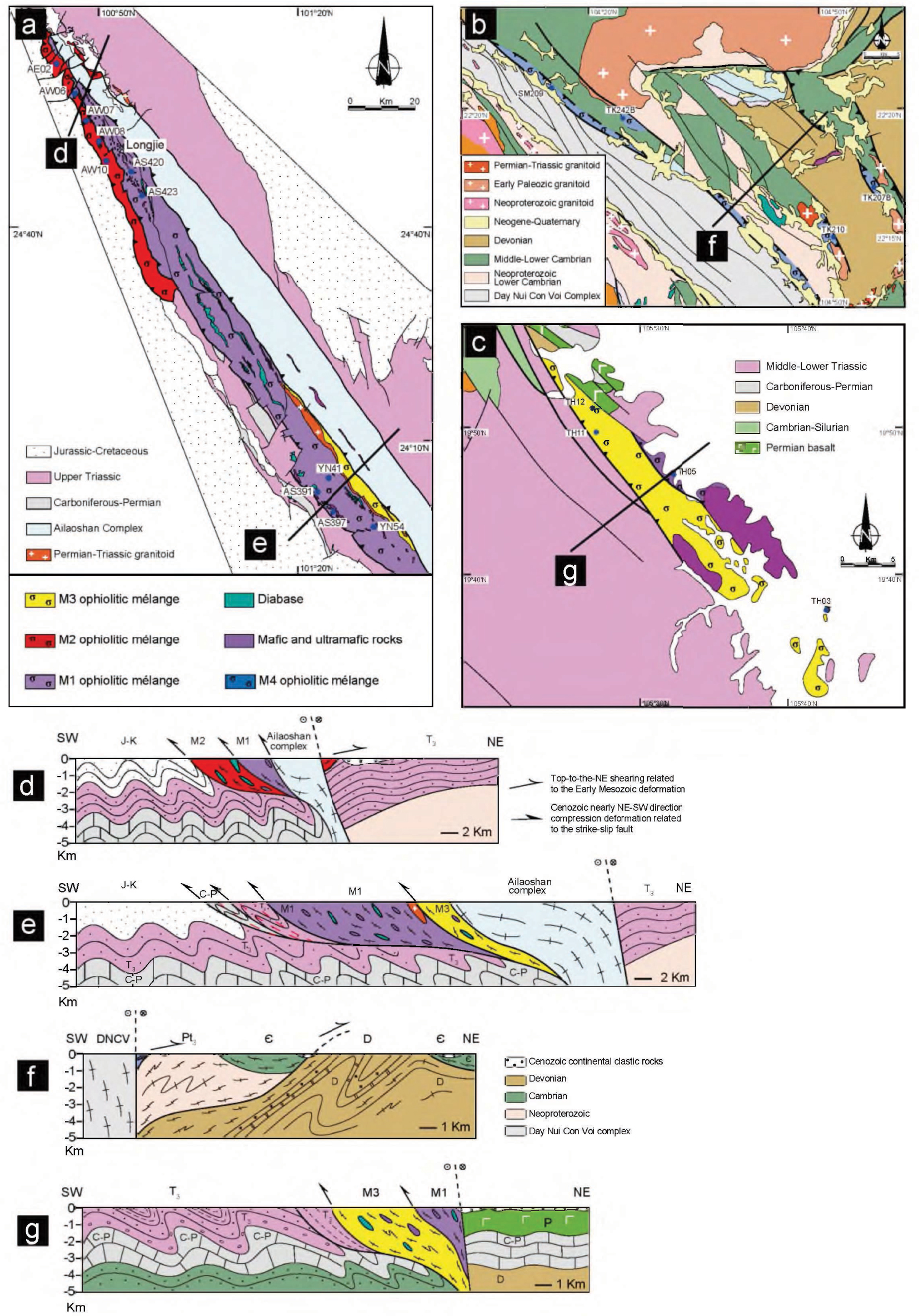

Although displaced during the Cenozoic extrusion, the Ailaoshan–Song Ma–Song Chay (AS–SM–SC) ophiolitic mélange is regarded as a uniform suture zone between South China Block (SCB) and Indochina Block (IB), developed during the Indosinian orogeny [Figure 1, Faure et al. 2014]. Ailaoshan, Song Ma, and Song Chay orogenic belts share similar litho-tectonic zones corresponding to the magmatic arc, ophiolitic mélange, and deformed Precambrian basement and cover series (foreland), and duplicated by the Cenozoic sinistral Red River Fault [Figure 1; Faure et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2022]. However, due to the extensive reworking during the Cenozoic extrusion of the IB, the ophiolitic mélange has been dismembered into three parts: Ailaoshan, Song Ma, and Song Chay. So, the study on the Ailaoshan–Song Ma–Song Chay ophiolitic mélange is critical to understand the interaction of SCB and IB. This paper summarises our previous work on the provenance analysis of the mélange matrix by detrital zircon and structural analysis. Then we discuss the temporal, strike-parallel, and strike-perpendicular heterogeneities of the AS–SM–SC ophiolitic mélange zone and argue for their significance for the evolution of the Eastern Paleozoic Tethys Ocean.

(A) Tectonic outline of east Asia [modified from Faure et al. 2014]. (B) Tectonic map of Southwest China-North Vietnam region, modified from the 1:15,00,000 Geological map of the five countries of southeast Asia and adjacent areas [Chengdu Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources 2006]. Nam Co: Neoproterozoic sedimentary rocks deformed and metamorphosed in Triassic; SC: Song Chay massif; ALMZ: Ailaoshan mélange zone; SMMZ: Song Ma mélange zone; SCMZ: Song Chay mélange zone; RRF: Red River fault; SCF: Song Chay fault; DBF: Dien Bien Phu fault; SD: Song Da belt; WALB: Western Ailaoshan belt; JP: Jinping zone. Masquer

(A) Tectonic outline of east Asia [modified from Faure et al. 2014]. (B) Tectonic map of Southwest China-North Vietnam region, modified from the 1:15,00,000 Geological map of the five countries of southeast Asia and adjacent areas [Chengdu Institute of Geology ... Lire la suite

2. Geological setting

The modern Southeast Asia consists of an assemblage of a series of continental blocks (e.g., Tarim, Qaidam, North Qiangtang, South Qiangtang, Lhasa, India, Sibumasu, Indochina, and South China). These microcontinents were successively rifted from northern Gondwana and then progressively accreted to the southern margin of Laurasia during the Late Paleozoic to Cenozoic, with the opening and closing of the Proto-, Paleo-, and Neo-Tethys oceans [e.g., Faure et al. 2014, 2018; Metcalfe 2002, 2011, 2013, 2021; Metcalfe et al. 2017; Sone and Metcalfe 2008]. The tectonic event related to the Eastern Paleo-Tethys Ocean closure was called the “Indosinian movement” [Deprat 1914, 1915; Fromaget 1932, 1941]. At the beginning of the 20th century, Deprat [1915] documented large-scale NE-directed thrusts and folds in NE Vietnam (also called Bacbo or Tonkin belt), and reported Alpine-like nappe structures and thin-skinned structures. The French geologist Fromaget called these pre-Late Triassic folds as “Indosinian fold system” [Fromaget 1932, 1941]. This view was further developed by Huang [1945] and he named such an Early Mesozoic orogeny the “Indosinian movement” which was well accepted by Chinese geologists. In the framework of plate tectonics, the concept of the “Indosinian movement” is attributed to the Early Mesozoic collision between the SCB and the IB recognised in southwestern China and northern Vietnam [Huang and Chen 1987]. Presently, large-scale Triassic deformation, magmatism, and metamorphism related to the closure of the Paleo-Tethys, or are well documented in South China, Indochina, Qiangtang, Lhasa, and Sibumasu blocks [Metcalfe 2021]. It is worth noting that the term “Indosinian” is used in different ways depending on the authors [Huang and Chen 1987]. Strictly speaking, “Indosinian” should be reserved for tectonic, metamorphic, or magmatic events developed before the Late Triassic unconformity of the continental red beds [Lepvrier et al. 2008]. However, “Indosinian” is also used to account for tectonic or magmatic events involving late Triassic and even Early Jurassic formations [Metcalfe 2021]. Indeed, the late Triassic–Early Jurassic events are not related to the IB-SCB collision but to the Sibumasu-IB collision or other collision. This young collisional event can be referred to as the Cimmerian orogeny or the Trans-Mekong one [Tran et al. 2020]. Meanwhile, these Triassic events were reworked by Late Mesozoic and Cenozoic tectonics [e.g., Leloup et al. 2001]. Usually, the classical Indosinian orogenic belt refers to the orogenic belt between IB and SCB, in North Vietnam and southwest China. Combined with previous studies, our detailed field work allows us to divide the Indosinian orogen into three parts, namely the Ailaoshan belt in SW China, the Song Ma belt in NW Vietnam, and the Song Chay belt in NE Vietnam. Faure et al. [2014] documented the similarities between the Ailaoshan, Song Ma, and Song Chay belts, and united these three belts as a single one, which was duplicated by the Cenozoic tectonics. Hence, the AS–SM–SC belt records the evolution history of one branch of the Eastern Paleo-Tethys Ocean between the SCB and IB.

2.1. Ailaoshan belt

Located in SW Yunnan Province, China, the NW–SE trending Ailaoshan belt is divided into four litho-tectonic zones from SW to NE, namely the Western Ailaoshan zone, Central Ailaoshan zone, Eastern Ailaoshan zone, and Jinping zone [Figure 1, Faure et al. 2016].

The Western Ailaoshan zone contains Permian to Early Triassic mafic–intermediate felsic volcanic rocks and intrusions considered as the products of subduction and collision [Lai et al. 2014b]. Different types of magmatic rocks formed in various tectonic settings, such as back-arc basins, arcs, or collision belts [Jian et al. 2009a, b; Lai et al. 2014b]. The subduction-related magmatic rocks include gabbro and quartz diorite [ca. 286 Ma; Jian et al. 2009a, b; Fan et al. 2010], Wusu-Yaxuanqiao basalt [287–265 Ma; Fan et al. 2010; Jian et al. 2009a, b], and basalt-rhyolite [249–247 Ma; Liu et al. 2011].

The Central Ailaoshan zone (Ailaoshan ophiolitic mélange zone) consists of blocks of serpentinized lherzolite and harzburgite, gabbro, plagiogranite, basalt, limestone, and radiolarites enclosed in quartz schist, micaschist, and pelitic schist (Figure 1). These pelitic rocks are interpreted as a “block-in-matrix” formation [Zhong 1998]. The ophiolitic blocks are mainly exposed to the NW of Mojiang City (Figure 2a). The gabbro yields amphibole 40Ar/39Ar ages at 339.2 ± 13.6 Ma and 349 ± 13 Ma [Zhong 1998; Jian et al. 1998]. The SHRIMP zircon U–Pb dating yields 362 ± 41 Ma, 328 ± 16 Ma/382.9 ± 3.9 Ma and 375.9 ± 4.2 Ma for gabbro, plagiogranite, and diabase respectively [Jian et al. 1998]. Major and trace element data and isotopic compositions of the Shuanghe gabbro suggest N-MORB type gabbro derived from a depleted mantle [Xu and Castillo 2004].

Geological and structural map of the Ailaoshan (a), Song Chay (b), and Song Ma (Thanh Hoa) (c) belts and related cross sections (d–g). The locations of the cross sections are indicated on the maps.

The Eastern Ailaoshan zone (i.e., the Ailaoshan complex) is composed of gneissic migmatite, augen gneiss, paragneiss, and granitic plutons [Cai et al. 2015]. U–Pb zircon geochronological dating documents three magmatic stages: Neoproterozoic (850–750 Ma), Early–Middle Triassic (250–240 Ma), and Cenozoic (30–20 Ma) [Zhang and Schärer 1999; Li et al. 2008; Qi et al. 2010; Cai et al. 2015]. This zone is mostly composed of high-grade amphibolite–granulite facies metamorphic rocks with Cenozoic ages, which is comparable to the Day Nui Con Voi of N. Vietnam. From the viewpoint of inherited zircons, these high-grade metamorphic rocks were exhumed to the surface from the lower crust along the Red River fault during the Cenozoic sinistral strike-slip fault [Tapponnier et al. 1990; Leloup et al. 1995].

The Jinping zone is a triangular wedge located in the southeastern Ailaoshan belt, comprising Ordovician–Carboniferous limestone, sandstone, and mudstone. Detrital zircons of Silurian sandstone show a SCB affinity, suggesting that the Jinping zone is the Paleozoic sedimentary cover of the SCB [Xia et al. 2016]. Late Permian ultramafic–mafic intrusive and volcanic rocks, which are parts of the Emeishan Large Igneous Province, are exposed in this tectonic zone [Xiao et al. 2004].

2.2. Song Ma belt

The Song Ma belt is bounded by the Dien Bien Phu fault and the Red River fault to the northwest and northeast, and extends over 300 km to the Thanh Hoa area (Figure 1). Four litho-tectonic units are recognised from SW to NE in the Song Ma belt, namely the Truong Son–Sam Nua zone, the Song Ma ophiolitic mélange zone, the inner zone, and the outer zone (Figure 1).

The NW–SE trending Truong Son–Sam Nua zone is mainly composed of Permian–Triassic sedimentary-volcanic rocks, which unconformably overlie the Neoproterozoic to Silurian sedimentary sequence. Carboniferous-Triassic (ca. 310–240 Ma) plutons and volcanic rocks have low 87Sr/86Sr(i) and δ18O values with high-Mg# values and are I-type with positive 𝜀Nd(t) and 𝜀Hf(t) values [Qian et al. 2019]. With enriched Sr–Nd–Hf isotopic compositions and depletions in Nb and Ta, these igneous rocks are interpreted as a continental magmatic arc related to the southwestward subduction of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean [Figure 3; Hou et al. 2019, and references therein]. The undeformed magmatic rocks, with ages between 240–220 Ma, are considered as formed by partial melting of crustal rocks in a post-collisional setting [Wang et al. 2022]. It is worth noting that the arc magmatism turns younger from SW to NE, indicating a NE-ward migration of the arc (Figure 3).

Simplified late Permian to Triassic granitoids distribution map of SW China and N. Vietnam [mostly on West Ailaoshan–Truong Son belt; adapted from Li et al. 2021] with the age distribution pattern inserted [ages are from Backhouse 2004; Cromie 2010; Fan et al. 2010; Halpin et al. 2016; Hieu et al. 2017; Hoa et al. 2008; Gan et al. 2021; Hotson 2009; Hou et al. 2019; Jian et al. 2009b; Kamvong et al. 2014; Lai et al. 2014a, b; Liu et al. 2012, 2015; Manaka 2008; Qian et al. 2016, 2019; Roger et al. 2012, 2014; Sanematsu et al. 2011; Shi et al. 2015; Shigeta et al. 2014; Tran et al. 2008, 2014; Wang et al. 2013, 2014, 2016b, 2018]. RRF: Red River Fault, SCF: Song Ca Fault; SMF: Song Ma fault; DBF: Dien Bien Phu fault. Masquer

Simplified late Permian to Triassic granitoids distribution map of SW China and N. Vietnam [mostly on West Ailaoshan–Truong Son belt; adapted from Li et al. 2021] with the age distribution pattern inserted [ages are from Backhouse 2004; Cromie 2010; ... Lire la suite

The Song Ma ophiolitic mélange zone is composed of micaschist and pelitic schist, serpentinized peridotite, harzburgite, dunite, plagiogranite, gabbro, gabbro-amphibolite, gabbro-dolerite, basalt, chert, and limestone blocks [Figures 1 and 2; Lepvrier et al. 1997; Vuong et al. 2013]. All these blocks, as well as the intensively sheared sedimentary rocks, experienced greenschist- to lower amphibolite facies metamorphism [Zhang et al. 2013].

Amphibolite and gabbro from the Song Ma ophiolitic mélange yield ages ranging between 387 Ma to 313 Ma [Sm–Nd whole rock, Vuong et al. 2013]. Our new work on a diorite lens yields SIMS zircon U–Pb age of 264.4 ± 1.8 Ma [Wang et al. 2022]. The foliated metagabbro yielded two age groups of 360.7 ± 3.0 Ma and 263.2 ± 2.3 Ma, interpreted as inherited and crystallisation ages respectively [Wang et al. 2022]. Along this zone in northern Laos, zircon U–Pb ages from the plagio-amphibolite yield a narrow age range of 367–356 Ma as xenoliths [Zhang et al. 2021]. Eclogite and HP granulite are reported in this area. Zircons and monazites from eclogite and granulite yield ages between 230 Ma and 243 Ma [Nakano et al. 2008, 2010; Zhang et al. 2013].

To the northeast of the Song Ma ophiolitic mélange zone, the inner zone, or Nam Co zone, is mainly composed of paragneisses, micaschists, quartz-schists, phyllites, amphibolites, quartzite, marbles, Paleozoic sandstone, siltstone, and limestone [Figure 1; Liu et al. 2012]. Most of these rocks underwent greenschist- to lower-amphibolite facies metamorphism. Detrital zircons from the metasedimentary rocks in this zone reveal a dominant age peak at ∼850 Ma [Hau et al. 2018], which suggests that the inner zone belongs to the SCB. The metamorphic age of 234 ± 10 Ma is revealed by the monazite U–Th–Pb dating [Nakano et al. 2010]. Meanwhile, biotite and muscovite 40Ar/39Ar dating in this zone yields the age of 250–240 Ma, recording a Triassic thermo-tectonic event [Lepvrier et al. 1997].

Further NE, the outer zone is located between the inner zone and the RRF (Figure 1). It is composed of weakly metamorphosed Paleozoic sedimentary rocks and Late Permian ultramafic–mafic intrusive and volcanic rocks of the Song Da area, equivalent to the Emeishan LIP of S China [Chung et al. 1997].

2.3. Song Chay belt

The Song Chay belt develops in NE Vietnam, extends to China, and is bounded by the Red River fault to its SW (Figure 1). From the SW to NE, this belt is divided into three litho-tectonic zones including the Day Nui Con Voi zone, the Song Chay ophiolitic mélange zone, and the NE Vietnam thrust-and-nappe system [Lepvrier et al. 2011].

The Day Nui Con Voi zone is bounded by the Red River and Song Chay faults to its southwest and northeast, respectively (Figure 1). This zone is composed of upper amphibolite to granulite-facies metamorphic rocks, forming an antiform [Leloup et al. 1995; Wang et al. 1998; Anczkiewicz et al. 2007]. It was exhumed from the middle to lower crust due to the Cenozoic Red River and Song Chay sinistral strike-slip faulting [Leloup et al. 1995; Wang et al. 1998; Nakano et al. 2018].

The Song Chay ophiolitic mélange zone is sporadically distributed along the NE flank of the Day Nui Con Voi complex [Figure 2b; Lepvrier et al. 2011]. The mélange tectonically overlies the Neoproterozoic to Cambrian strata. It consists of sheared and metamorphosed sandstone and mudstone forming the matrix of serpentinized ultramafic rocks, gabbro, gabbro-diorite, plagiogranite, chert, and limestone as blocks. A plagiogranite yielded a zircon crystallisation age of 356.4 ± 2.9 Ma, interpreted as the opening time of the Paleo-Tethys [Wang et al. 2022].

The NE Vietnam thrust-and-fold system is located to the northeast of the Song Chay ophiolitic mélange zone, formed during the collision of the SCB and IB [Figure 1; Lepvrier et al. 2011]. It is subdivided into an inner zone and an outer zone according to the structural style and metamorphism. The inner zone, bounded by Song Chay and Malipo faults, is composed of greenschist- to amphibolite facies metamorphosed Neoproterozoic to Early Paleozoic sedimentary rocks and the Early Paleozoic Song Chay augen gneiss massif, having experienced a top-to-the-NE ductile shearing [Wang et al. 2021]. Along the mineral and stretching lineation, biotite and muscovite 40Ar/39Ar ages document a deformation age at 250–240 Ma [Wang et al. 2022, and references therein]. The outer zone is characterised by weakly to un-metamorphosed Late Paleozoic sedimentary rocks that were involved in a fold-and-thrust belt [Lepvrier et al. 2011]. Granitic plutons dated between 428 and 87 Ma are widely distributed [Chen et al. 2014, and references therein]. It is worth noting that the foliated plutons are older than 245 Ma, while the undeformed ones are younger than 245 Ma.

3. The AS–SM–SC ophiolitic mélange zone, from the viewpoint of matrix detrital zircon

Due to the dextral offset along the Dien Bien Phu fault, a pre-Tertiary reconstruction places the Song Ma belt to the southeast of the Ailaoshan belt. By doing so, the tectonic units in the two belts correlate well with each other [Wang et al. 2022, and references therein]. Accordingly, we describe the zircon U–Pb ages and Lu–Hf isotopic composition of the Ailaoshan and Song Ma ophiolitic mélange zones together. Based on a systematic work on the detrital zircon age spectra and Lu–Hf isotopic composition of the matrix of the mélange, three mélange units, namely, M1 (Mélange 1), M2, and M3 can be distinguished (Figures 1 and 2).

3.1. Zircon U–Pb ages and Lu–Hf isotopic composition of the Ailaoshan–Song Ma ophiolitic mélange zone

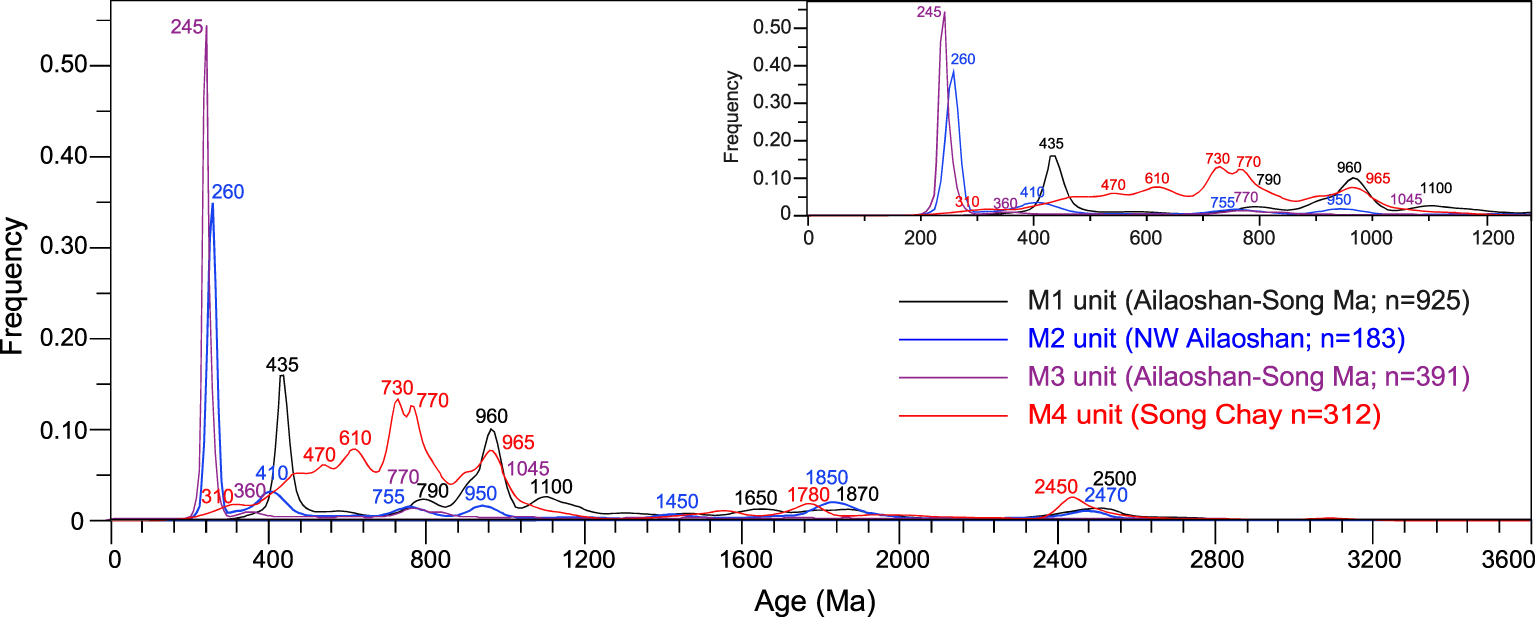

The M1 unit is mainly exposed in the NW to the central segment of the Ailaoshan ophiolitic mélange zone and the easternmost part of the Song Ma zone (Thanh Hoa area) (Figures 1, 2a, c). The analysed samples from the matrix consist of sheared siltstone (AS391, AS405), sandstone (AS397, AS420, AS147), sericite schist (AS103), siltstone (AW06), sublithic arenite (YN-54), and mylonitic siltstone (YN-41) in the Ailaoshan belt and sandstone (TH05) in the Thanh Hoa area [Table 1 and Figure 2c; Xia et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2023]. In these samples, the detrital zircon age distribution shows two significant peaks at ∼435 Ma and ∼960 Ma and five secondary peaks of ∼790 Ma, ∼1110 Ma, ∼1650 Ma, ∼1870 Ma, and ∼2500 Ma (Figure 4). The M1 unit has several Late Paleozoic zircons with a cluster at 355–375 Ma (1.3% of the total measurement), indicating the maximum depositional age of the matrix. Meanwhile, these Phanerozoic zircons yield 𝜀Hf(t) ranging from −25.4 to +12.0, and seventy-two percent are negative, which have the TDM2 (two-stage model) ages ranging from 750 to 3960 Ma (Figures 5 and 6).

Synthetis and comparison of the cumulative probability plots of detrital zircon U–Pb ages from the Ailaoshan–Song Ma–Song Chay belt.

Temporal variations of 𝜀Hf(t) values versus ages at 0–3000 Ma from M1, M2, M3, SW Yangtze block, and ELIP (Emeishan Large Igneous Province).

Temporal variations of TDM2 versus ages at 0–3000 Ma from M1, M2, M3, and ELIP (see Figure 4 for relevant statistics data).

Summary of the measurements of youngest age of detrital zircon grains in Ailaoshan–Song Ma–Song Chay belt

| Ophiolitic mélange unit | Sample | YSG | YPP | YC1σ (2+)a | YC2σ (3+)a | Probable depositional age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | AS391 | 251.4 ± 2.9 | 435 | 414.1 ± 3.3 (2) | 418.7 ± 3.9 (3) | (355?) 310–270? |

| AS397 | 355.0 ± 3.9 | 430 | 357.7 ± 3.7 (4) | 360.0 ± 3.8 (5) | ||

| AS405 | 358.3 ± 5.1 | 435 | 423.2 ± 4.9 (6) | 423.3 ± 5.1 (10) | ||

| AS420 | 394.7 ± 4.3 | 435 | 415.8 ± 5.1 (2) | 423.6 ± 4.8 (8) | ||

| AS423 | 414.4 ± 3.8 | 425 | 417.5 ± 4.2 (4) | 424.6 ± 4.6 (13) | ||

| TH05 | 263.3 ± 2.2 | 439 | 370.4 ± 2.6 (2) | 435.6 ± 3.7 (17) | ||

| AS103 | 371.4 ± 3.9 | 432 | 435.5 ± 4.6 (12) | 435.5 ± 4.6 (12) | ||

| AS147 | 373.7 ± 3.8 | 425 | 436.4 ± 4.6 (6) | 428.6 ± 4.5 (8) | ||

| AW06 | 261.5 ± 2.47 | 460 | 444.3 ± 5.9 (2) | 450.1 ± 5.5 (3) | ||

| YN-54 | 427.2 ± 6.7 | 440 | 441.5 ± 6.0 (9) | 449.2 ± 6.6 (11) | ||

| YN-41 | 399.7 ± 5.1 | 440 | 401.3 ± 4.7 (2) | 435.1 ± 5.5 (15) | ||

| M2 | AE02 | 229 ± 4.6 | 250 | 259.8 ± 3.2 (3) | 254.6 ± 2.8 (5) | 260–255 |

| AW07 | 239 ± 2.2 | 260 | 258.3 ± 2.9 (18) | 257.3 ± 2.8 (19) | ||

| AW08 | 242 ± 2.8 | 260 | 260.0 ± 2.7 (39) | 259.5 ± 2.7 (41) | ||

| AW10 | 232.4 ± 2.4 | 260 | 258.3 ± 2.5 (7) | 258.3 ± 2.5 (7) | ||

| M3 | AW17 | 237 ± 3 | 245 | 243.3 ± 2.5 (47) | 244.2 ± 2.5 (49) | ∼245 (250–245) |

| AW20 | 236 ± 3 | 245 | 244.9 ± 2.4 (29) | 244.9 ± 2.4 (29) | ||

| 13YZ06 | 236 ± 2 | 245 | 246.9 ± 2.4 (31) | 246.9 ± 2.4 (31) | ||

| TH03 | 223.2 ± 11.0 | 240 | 242.6 ± 6.2 (20) | 242.6 ± 6.2 (20) | ||

| TH11 | 117.0 ± 21.3 | 247 | 249.3 ± 6.7 (99) | 249.3 ± 6.7 (99) | ||

| TH12 | 224.4 ± 4.8 | 245 | 244.7 ± 4.8 (69) | 244.7 ± 4.8 (69) | ||

| M4 | TK242B | 271.2 ± 2.5 | 550 | 308.3 ± 2.6 (3) | 308.3 ± 2.6 (3) | 310–255 |

| TK210 | 295.3 ± 1.9 | 490 | 431.9 ± 3.5 (2) | 424 ± 3.4 (4) | ||

| TK207B | 236.4 ± 1.7 | 490 | 460.9 ± 4.0 (2) | 484.7 ± 3.4 (9) | ||

| SM209 | 255 ± 4 | 460 | 255.5 ± 4.0 (2) | 464.2 ± 7.0 (6) |

Notes: YSG: youngest single grain age; YPP: youngest graphical age peak; YC1σ (2+): youngest 1σ grain cluster; YC2σ (3+): youngest 2σ grain cluster. a Numbers of grain ages in clusters in parentheses.

The M2 unit located in the NW segment of the Ailaoshan ophiolitic mélange zone, close to Permian strata following the previous geological map (Figure 2a). The previous analytical work contains the quartz arenite (AE02), sandstone (AW07, AW08), and quartz-arenite (AW10) belonging to the M2 unit [Table 1 and Figure 2a; Xia et al. 2020]. Detrital zircons analysis reveals that the M2 unit ages cluster around 240–270 Ma, peaking at ∼260 Ma with secondary peaks at ∼410 Ma, ∼755 Ma, ∼950 Ma, ∼1450 Ma, ∼1850 Ma, and ∼2470 Ma [Figure 4; Xia et al. 2020]. The 𝜀Hf(t) of the zircons with 240–270 Ma ages range from −28.9 to +8.1, clustering around −1.0 to +7.0 and showing a mantle-derived material contribution (Figure 5). The TDM2 ages of these zircons range from 0.67 Ga to 2.53 Ga with a significant Neoproterozoic peak of ∼0.85 Ga (Figure 6).

The M3 unit is exposed in the SE segment of the Ailaoshan ophiolitic mélange and the Thanh Hoa area (Figure 2). It forms the main part of the mélange zone (Figure 1). The M3 unit includes siltstone (AW17, 13YZ06), and mudstone (AW20) in the Ailaoshan belt, and siltstone (TH03), schistose tuff (TH11), and schistose sandstone (TH12) in the Thanh Hoa area [Table 1 and Figure 2; Xu et al. 2019; Li et al. 2021]. The detrital zircons of the M3 unit yield a significant age peak at ∼245 Ma with three secondary peaks at ∼360 Ma, ∼770 Ma, and ∼1045 Ma (Figure 4). The dominant zircons at 230–260 Ma have 𝜀Hf(t) values ranging from −21.9 to +10.1 and TDM2 ages from 0.55 Ga to 2.62 Ga, respectively (Figures 5 and 6). Besides, more than eighty-four percent of the 230–260 Ma zircons have negative 𝜀Hf(t) values from −17 to −5 (Figure 5), indicating that the M3 detrital zircons are sourced from the continental crust. Although both M2 and M3 units have Late Permian to Early Triassic detrital zircons, the different Hf isotopic compositions of these zircons allow distinguishing the M3 unit from the M2 one (Figure 5).

3.2. Zircon U–Pb ages and Lu–Hf isotopic composition of the Song Chay ophiolitic mélange zone

Along the Red River fault, four samples were analysed from the matrix of the Song Chay ophiolitic mélange, including sheared meta-sandstone (TK242B, TK210, TK207B) and a lithic sandstone (SM209) (Figure 2a). To keep consistency, this mélange zone will be referred to as M4 in the following. The analytical results show peak ages at 315 Ma, 470 Ma, 610 Ma, 730 Ma, 770 Ma, 965 Ma, 1780 Ma, and 2450 Ma, which are significantly different from M1, M2, and M3 units (Figure 4). In these samples, the 𝜀Hf(t) values of the detrital zircons range from −28.2 to +10.8, and the TDM2 ages range from 0.97 Ga to 3.87 Ga [Wang et al. 2021].

4. Discussion

4.1. Deposition age of the AS–SM–SC ophiolitic mélange from the viewpoint of the detrital zircon age distribution

As formed in the turbidity deposits, it is difficult to determine the biostratigraphic age of the mélange matrix using the fossils contained in the strata [Caridroit and de Wever 1984; Yu and Tekin 1996]. Moreover, most of the mélanges experienced intensive deformation and metamorphism during subduction, collision, and exhumation. Therefore, the matrix mostly is generally represented by pelitic schist, micaschist, and even paragneiss [Festa et al. 2010, 2012]. Hence, it is difficult to constrain the depositional age of the matrix of the mélanges.

To determine the maximum depositional age of the sedimentary rocks, Dickinson and Gehrels [2009] tested four alternate measurements: YSG: Youngest Single Grain age with 1σ uncertainty, but inherent lack of reproducibility diminishes confidence in its reliability because some individual YSG ages might be spurious due to lead loss or grain of unknown origin; YPP: Youngest graphical age Peak on an age-probability Plot-controlled by more than one grain age (single-grain age peaks ignored), the crest of the discrete youngest age peaks visible on age-distribution curves; YC1σ (2+): Youngest 1σ grain Cluster (two or more grains)—provides a numerical measure of youngest grain age incorporating a similar minimal reproducibility as YPP; and YC2σ (3+): Youngest 2σ three or more grains Cluster—provides a more statistically robust and conservative measure of youngest age. In fact, from the viewpoint of our analytical work on the zircon from the matrix of the mélange, all these estimations have significant uncertainties (Table 1). The maximum depositional age should also consider regional geology constraints.

According to the YSG age of the M1 unit, the feasible depositional age ranges from 251 Ma to 427 Ma. However, the YPP, YC1σ (2+), and YC2σ (3+) give depositional ages at around 430–440 Ma, 357–441 Ma, and 360–449 Ma, respectively (Table 1). The detrital zircons of the M1 unit are mainly supplied from the Silurian and Devonian substratum, and Truong Son–Sam Nua arc-related felsic magmatism [Li et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2023]. The deposition time of M1 is restricted to ca. 310 Ma, which corresponds to the initial development stage of the magmatic arc [e.g., Zhang et al. 2021]. The Truong Son–Sam Nua arc activity can be divided into two stages, A1 and A2, between 310–270 Ma and 265–240 Ma with peaks at 286 and 248 Ma, and a gap between 270–265 Ma (Figure 3). If we consider that the A2 signal is significant in M2, and absent in M1, the depositional age of the M1 should be constrained between 310 Ma and 270 Ma (Table 1).

The possible depositional age of the M2 unit suggested by the YSG is between 242–229 Ma (Table 1). However, all the YPP, YC1σ (2+) and YC2σ (3+) have a consistent age of 260–255 Ma (Table 1). According to Cawood et al. [2012], if the deposition forms at the edge of converging plates, such as the trench, and the age of detrital zircons have a dominant age peak, then the largest proportion of ages is close to the depositional age. Considering the provenance analysis, a possible deposition time of the M2 unit is constrained between 260 Ma and 255 Ma (Table 1).

The YSG age of the M3 unit is 237–117 Ma, while the YPP, YC1σ (2+), and YC2σ (3+) give ages between 240 Ma and 250 Ma clustering around 245 Ma (Table 1). In the fold-and-thrust unit of the Song Ma belt, the biotite and muscovite yield 40Ar/39Ar ages of 250–240 Ma corresponding to the timing of the collision [Lepvrier et al. 1997]. The matrix of the mélange should be deposited earlier than this age. Accordingly, the possible depositional age of the M3 unit is constrained at 245 Ma (Table 1).

In the M4 unit, the YSG give possible depositional ages of 295–236 Ma (Table 1). However, the YPP gives older ages between 460 Ma and 550 Ma (Table 1). Besides, the YC1σ (2+) and YC2σ (3+) give ages of 255–460 Ma and 308–484 Ma respectively. Since the youngest age cluster is around 310 Ma (∼5.4%), the deposition age should be younger than the Late Carboniferous. Considering that the deformation and metamorphism occurred earlier than the Late Triassic in the Song Chay ophiolitic mélange zone [Lepvrier et al. 2011], we suggest that its maximum deposition age is older than ∼255 Ma [Wang et al. 2021].

Overall, the detrital zircon age analyses suggest that the mélange matrix has different depositional times in the AS–SM–SC belt (Table 1). It looks like the mélange matrix is characterised by temporal heterogeneity.

4.2. Provenance and strike-parallel heterogeneity of the different ophiolitic mélange units

In the AS–SM–SC belt, the matrix in different areas has different depositional times and provenances, manifesting obvious strike-parallel heterogeneity, namely, variations along the NW–SE trend, parallel to the strike of the orogenic belt [Lin et al. 2022].

As the main peaks of M1 unit, the spectrum of 435 Ma and 960 Ma also appear in the Paleozoic sedimentary rocks of IB and the Cathaysia block [Figure 4; Xia et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016a]. However, the Hf isotopic composition of the M1 unit is more like that of the IB Paleozoic strata rather than the Cathaysia block ones, particularly to the Silurian and Devonian sedimentary rocks of the Eastern Simao in the IB [Wang et al. 2016a; Xia et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2023]. In particular, as the major age group (400–500 Ma), detrital zircons from the M1 unit and Silurian and Devonian sedimentary rocks in the IB share the same age spectrum, similar 𝜀Hf(t) values, and TDM2 ages [Liu et al. 2023]. Accordingly, the above-mentioned strata of the IB are the major provenance of the M1 unit (Figure 7). In the Ailaoshan–Song Ma suture zone, gabbro, diabase, and anorthosite which were dated to ca. ∼370 Ma were interpreted as emplaced during the initial opening of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean [Jian et al. 2009b]. Considering this magmatism, we can argue that contemporary felsic magmatism acts as the potential provenance for the M1 unit, providing the youngest detrital zircons around 370 Ma.

Paleogeographic reconstruction of SCB and IB at 260 Ma. Arrow indicated paleo-current.

Except for a younger prominent cluster with ages of 270–240 Ma (peak at 260 Ma), the M2 and M1 units are correlatable in terms of detrital zircon spectrum (Figure 4). Consequently, the provenance of the M2 unit is supposed to be from the magmatic arc (Truong Son–Sam Nua) and Paleozoic strata of the IB [Xia et al. 2020]. However, the 𝜀Hf(t) values (−28.9 to +8.1) and model ages (2.53 Ga to 0.67) from the dominant age spectrum (270–240 Ma) are like the zircons in ELIP (Emeishan Large Igneous Province), rather than the Late Permian–Middle Triassic magmatic zircons from Western Ailaoshan–Truong Son–Sam Nua magmatic arc zone (Figures 5 and 6). Hence, we argue that the 270–240 Ma detrital zircons, at least half of them (positive 𝜀Hf(t) values, 52%), might come from the ELIP, i.e., the passive margin of SCB. Particularly, if we restore the initial location, before the sinistral strike-slip displacement of the Red River fault, the ELIP becomes located close to the Ailaoshan belt (Figure 7).

In the M3 unit, the detrital zircons have a dominant peak around 245 Ma (Figure 4). Meanwhile, the 𝜀Hf(t) values (more than 84% are negative) and model ages of these 260–230 Ma zircons are consistent with the widespread 255–245 Ma arc-related magmatic rocks of IB (A2 in Figure 3). Therefore, this dominant cluster was directly supplied by the overriding IB (Figure 7). Like the M1 unit, the signal of 360 Ma is also sourced from the magmatic rocks related to the opening of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean in M3 unit. Besides, the Precambrian detrital zircons of the M3 unit show two peaks of 770 and 1045 Ma (Figure 4). The typical ages of 440 Ma and 960 Ma of IB signature spectrum are missing in the M3 unit, which suggests that the Paleozoic sequences in IB may not have supplied the material of the M3 unit. However, the 770 Ma peak appears as a major age group of the Paleozoic sedimentary rocks in the southwest margin of the SCB [Li et al. 2021]. Accordingly, it could be concluded that the provenance of M3 units is from both magmatic arcs of IB and Paleozoic sedimentary rocks in the SCB [Figure 7; Li et al. 2021].

The matrix M4 unit shows two peaks at 310 Ma and 460 Ma. There is no obvious 310 Ma peak in the sedimentary rocks of SCB and IB, while ∼300 Ma magmatic rocks were reported in the Truong Son–Sam Nua zone [Kamvong et al. 2014]. The 460–440 Ma zircons are widely distributed in the Paleozoic strata of the IB and Paleozoic granite of the SCB [Wang et al. 2011, 2016a]. Their 𝜀Hf(t) values are almost negative and resemble the magmatic zircons of Paleozoic granite in the SCB but different from the Paleozoic strata of the IB [Wang et al. 2021]. The Neoproterozoic detrital zircons are grouped into predominant 800–700 Ma and subordinate 650–550 Ma and 1000–900 Ma (Figure 4). The group of 800–700 Ma is the main peak of the sedimentary rocks of the SCB, while it is the subordinate peak in the IB [Sun et al. 2009]. In the northwestern to the western margin of the SCB, the Neoproterozoic to Paleozoic strata have abundant 650–550 Ma detrital zircons, but a few ones are preserved in the Paleozoic strata of the IB [Wang et al. 2016a; Xia et al. 2016]. Both in the SCB and IB, the Paleozoic strata contain a multitude of 1000–900 Ma zircons. Considering that the Neoproterozoic zircons represent more than 60% of the analysed grains, we suggest that the zircons of the M4 unit are dominantly supplied from the SCB, with a small number of Late Carboniferous (∼310 Ma) zircons sourced from the magmatic arc in the IB [Wang et al. 2021].

As shown in Figure 7, the matrix of the AS–SM–SC ophiolitic mélange manifests obvious strike-parallel heterogeneity. Importantly, our results demonstrate that the detrital materials of the mélange matrix could be provided by both the active continental margin of the IB and the passive continental margin of the SCB (Figure 7).

4.3. Strike-perpendicular heterogeneity

Our results document a strike-perpendicular heterogeneity of the AS–SM–SC ophiolitic mélange with variations along the NE–SW trend, transverse to the orogenic belt. In the field, the M1 unit is located to the NE of the M2 unit in the northwestern segment of the Ailaoshan ophiolitic mélange zone (Figure 2a). The NE-dipping of the foliation indicates that the M1 unit is geometrically above M2. The Ailaoshan complex formed by Cenozoic upper amphibolite to granulite facies metamorphic rocks also overlies the M1 (Figure 2d). Thus, the M1 and M2 units and the Ailaoshan complex appear as inverted. In the central segment of the Ailaoshan ophiolitic mélange, the M3 unit, located to the northeast of the M1 unit overlies this unit (Figure 2a). On the contrary, the high-grade metamorphic rocks of the Ailaoshan complex, are located above the M3 unit (Figure 2e). Further SE, at the coastal end of the Song Ma belt (Thanh Hoa area), the M1 unit overlies the M3 unit, where the M2 unit and high-grade metamorphic rocks are missing (Figure 2c, g). The presently inverted geometry of the M1, M2, and M3 units and the Ailaoshan complex can be attributed to the Cenozoic transpressional tectonics related to a strike-slip deformation (Figure 2).

4.4. Implications of the paleogeography and the tectonic evolution of the eastern Paleo-Tethys

It is well acknowledged that from the Devonian, several continental blocks, such as SCB, IB, Sibumasu, North Qiangtang, and South Qiangtang, were separated from Gondwana, drifted to the north, and collided with Laurasia. This rifting was coeval with the opening and closure of the oceanic basins ascribed to several branches of the Paleo-Tethys. In the study area, the AS–SM–SC Ocean, opened between SCB and IB, was one of the branches of the Paleo-Tethys. As mentioned above, the M1, M2, M3, and M4 units contain detrital zircon age clusters between 380 to 355 Ma that may be ascribed to the oceanic magmatism related to the initial opening of the Paleo-Tethys (Table 1; Figures 4 and 8A).

Tectonic evolution between the SCB and IB from Late Devonian to Cenozoic times.

During the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian (310–270 Ma), this branch of the Paleo-Tethys subducted beneath the IB and formed the NW–SE striking Jiangda-Weixi, Western Ailaoshan–Truong Son–Sam Nua magmatic arc (A1 in Figure 3) along the north margin of IB [Figure 7; Liu et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2018]. During this period, the Silurian and Devonian strata, that is, the cover of the IB, rather than the magmatic arc provided detritic material for the M1 unit [Figure 8B1; Li et al. 2021]. Meanwhile, the Paleozoic sedimentary rocks of the passive continental margin of the SCB acted as the main source of sediments in the Song Chay ophiolitic mélange zone (Figure 8B2).

During the 270–265 Ma period, a magmatic quiescence occurred in the Western Ailaoshan–Truong Son–Sam Nua zone (Figure 3). At that time, the ELIP and related acid magma erupted to the SW of the SCB, providing abundant detritic materials for the M2 unit (Figure 8C). Subsequently, in the Western Ailaoshan–Truong Son–Sam Nua zone, the second-stage arc-related magmatism (260–250 Ma) occurred (A2 in Figure 3, D1 in Figure 8). A change in the subduction angle is suggested by the northeastward magmatic arc migration (Figure 3). During this period, the provenance of the matrix of the M3 mélange was supplied by the A2 magmatic arc (D1 in Figure 8).

At approximately 250 Ma, the SCB subducted southwestward beneath the IB, accompanied by large-scale regional metamorphism and deformation that continued up to 240 Ma [Lepvrier et al. 1997]. In the SCB, the top-to-the-NE shearing and related fold and thrust deformation were developed. During this period, the M1, M2, and M3 units were thrust upon the Neoproterozoic–Early Mesozoic sedimentary cover (Figure 8D2). Afterwards, a large-scale magmatism occurred at 240–220 Ma, representing a post-collisional stage [Figure 8E; Roger et al. 2014].

In the Cenozoic, the India-Eurasia continental collision led to the eastward extrusion of the IB along the sinistral strike-slip Red River and Dien Bien Phu faults [Tapponnier et al. 1990; Leloup et al. 1995]. Accompanied by this strike-slip deformation, the southwestward thrusting caused an inverted geometry of the M1, M2, and M3 units and the Ailaoshan complex (i.e., strike-perpendicular heterogeneity, Figure 8F).

The AS–SM–SC belt is duplicated by the Cenozoic strike-slip Red River and Dien Bien Phu faults [Faure et al. 2014]. Such a Cenozoic superimposition forms a complex architecture, that is, the juxtaposition of several orogenic belts or suture zones (Figure 7). Accordingly, we think of the Paleo-Tethys as an ocean surrounded by microcontinents and lacking islands, rather than an archipelagic ocean as the present Pacific Ocean (Figure 9). It should be noted that the passive continental margin of the SCB acted as a significant provenance area for the matrix of the mélange (Figure 7). Furthermore, the Paleo-Tethys is a “narrow” or “limited” ocean, like the present Black Sea (Figure 9). This interpretation could improve the understanding of the Late Permian to Early Triassic paleogeographic reconstructions (Figure 9). Several lines of evidence, including the Early Triassic acidified/sulfurised/overheated ocean causing the slow recovery after the mass extinction, the lack of porphyry copper deposits in the Paleo-Tethys, and the analogous Lopingian quadruped fauna in the northern margin of the North China block and the IB (Laos), also support this conclusion [Richards and Şengör 2017; Hu et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2021].

Global plate reconstruction in Early Triassic times of the Paleo- and Neo-Tethys Ocean evolution [modified from Zhu et al. 2021].

5. Conclusion

Based on the structural analysis and regional tectonics, the review of detrital zircons age distribution and Hf isotopes in the mélange zone between the SCB and IB allows us to draw the following conclusions:

- The geochronological data of the detrital zircons from the matrix of the AS–SM–SC ophiolitic mélange zone document a temporal heterogeneity between M1, M2, M3, and M4 units at 310–270 Ma, 265–250 Ma, 245–240 Ma, and 310–255 Ma, respectively.

- The different components and provenances of each unit reflect a strike-parallel heterogeneity. The M1 unit was mainly sourced from the Paleozoic sedimentary rocks of the IB. The main provenance for the M2 unit is Emeishan large igneous province. The magmatic arc developed in the IB provided the materials for the M3 unit, and the detrital materials of the M4 were mainly sourced from the SCB. The Cenozoic strike-slip deformation led to an inverted geometry of the M1, M2, and M3 units, accounting for a strike-perpendicular heterogeneity straight to the strike of the orogenic belt.

- The temporal, strike-parallel, and strike-perpendicular heterogeneities help to decipher the time-space evolution of the Paleo-Tethys. The M1, M2, M3, and M4 units contain information from different evolutionary stages, likely recording the comprehensive history of the ancient oceanic basin. Importantly, our results demonstrate that both the active continental margin of the IB and the passive continental margin of the SCB supplied significant material for the mélange matrix, indicating that the Paleo-Tethys Ocean was a “narrow” or “limited” ocean rather than the archipelagic ocean proposed before.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SKL-Z202205) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91855212 and 91855103). The editor O. Fabbri and two reviewers are thanked for their constructive comments and suggestions, which lead to a significant improvement in our manuscript. Mr. J. Y. Li is acknowledged for his help during the fieldwork.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0