1 Introduction

The enzymatic activities of the threonine pathway in Escherichia coli are sensitive to pollutants such as cadmium, copper and mercury, which, even at low concentration, can substantially decrease or even block the pathway at several steps. Such multiple sites of action must be taken into account when considering two important environmental roles of bacteria: in bioremediation of soils and as commensals of mammalian organisms.

The effects that can arise in the interaction between threonine pathway and general inhibitors that can have multiple site of interaction such as pollutants are complex. For this reason, a computer simulation of the threonine pathway synthesis [1–3] was used. This model is based on kinetic functions developed from measurements on the pathway enzymes under near-physiological conditions. In order to represent the effects of the different pollutants on the threonine pathway, the model was extended with kinetic terms for the inhibition.

For this purpose, the kinetic parameters describing these inhibitions have been determined experimentally. In the first part of this experimental work, the more potent inhibitors were chosen by screening. Then the effects of these compounds on the different steps of the pathway were measured by titration of the enzyme activities.

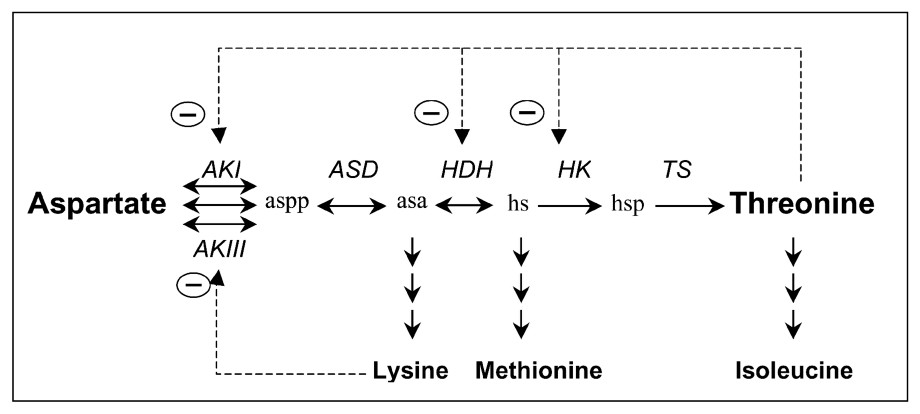

The threonine pathway in E. coli involves five steps from aspartate (Fig. 1). The first step is important owing to its regulation. It is catalysed by three isoenzymes: the aspartokinase I (AKI), which is inhibited by threonine, and the synthesis of which is repressed in presence of threonine and isoleucine (an amino acid synthesized from threonine); aspartokinase III (AKIII), which is inhibited by lysine (which is also synthesized from aspartate in E. coli), and the synthesis of which is repressed by lysine; and aspartokinase II (AKII), the synthesis of which is repressed by methionine, an amino-acid synthesized from aspartate in E. coli (for a review, see Cohen [4] and Neidhardt [5]). AKI and AKII are bifunctional enzymes that also catalyse the homoserine dehydrogenase reaction (AKI-HDHI and AKII-HDHII). The amount of aspartokinase II-homoserine dehydrogenase II is low, so it may be omitted in an initial modelling approach.

Threonine pathway from threonine in E. coli. The different steps are catalysed by aspartokinases I, II and III (AKI, AKII and AKIII), aspartate semi-aldehyde dehydrogenase (ASD), homoserine dehydrogenase (HDH), homoserine kinase (HK) and threonine synthase (TS). β-aspartyl phosphate (aspp), aspartic β-semialdehyde (asa), homoserine (hs) and O-phosphohomoserine (hsp) are the intermediate metabolites. means retroinhibition.

The model will allow simulation not only of threonine production as a function of pollutant concentrations but also of the variations of control coefficients and of the partial response coefficients [6–10]. We will show that these parameters are useful for understanding the pollutants' effects on the whole threonine pathway.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Cells

An E. coli strain K12 thiaisoleucine-resistant derivative (Tir-8) [11], de-repressed for the threonine operon [12], was used in the study. Bacteria were grown in a minimal medium at 37 °C with 0.4% (w/v) glucose as the carbon source. At the end of the exponential phase, the cells were harvested, washed and frozen at −80 °C in extraction buffer.

2.2 Chemicals

The different pollutants tested, KNO3, KNO2, CuCl2, CdCl2, HgCl2 and ZnCl2, were purchased from Sigma. The other chemicals were as described by Chassagnole et al. [1].

2.3 Enzyme assays

The details of this work can be found in a previous paper [1].

2.4 Initial screening

In order to study the pollutants' effects, we decided in the first instance to determine the potential inhibitions by all of these compounds through a rough screening on all the enzymatic activities, at 5 mM or the highest possible concentration given the solubility of the compound in the buffer. All the activities were measured at substrate concentrations around the Km value and the percentage inhibition calculated relative to controls.

2.5 KI, IC50 and Hill-coefficient determination

Each enzyme activity was measured as a function of the concentration of the inhibitory ion. The KI and the Hill coefficient were determined by fitting the inhibition curves with a classical Hill equation using SigmaPlot 2000.

2.6 Threonine pathway model

The threonine pathway model used here is the culmination of a combined experimental and theoretical study, the details of this work can be found in [1–3]. In order to reproduce the in vivo the steady state of the pathway, the measured in vivo concentrations of the different substrates and effectors and the enzyme activities have been introduced into the model.

2.7 Incorporation of the effects of heavy metals in the model

In order to represent the effects of the different heavy metals on the different steps of the threonine pathway, a non-competitive inhibition term, with a Hill coefficient, had been incorporated in each enzymatic rate equation (equation (1)).

| (1) |

2.8 Simulation

The dynamic modelling of the flux, the intermediates metabolites and the flux control coefficient determinations have been done with the SCAMP (Simulation, Control Analysis, Modelling Package) software developed by Sauro and Fell [13–16]. With this software, the flux control coefficients and the overall flux response coefficient to an inhibitor are determined by numerical perturbations of the enzyme activities or inhibitor concentration respectively and recalculation of the corresponding steady state over a specified range of inhibitor concentrations. The program also allows calculation of enzyme elasticity with respect to the inhibitors, and partial response coefficients (the product of an enzyme's flux control coefficient and elasticity with respect to an inhibitor) [6] in order to assess the relative contribution of each enzyme to the total response to the inhibitor.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Initial screening

The pollutants tested on the threonine pathway were nitrate, nitrite, copper, cadmium, mercury and zinc. The results of the initial screen of each of these compounds are shown in Table 1.

Percentage of inhibition of toxic compound on enzyme activities

| mM | AKI | AKIII | ASD | HDHI | HK | TS | |

| Nitrate | 5 | 14 | n.I. | n.I. | n.I. | n.I. | n.I. |

| Nitrite | 5 | n.I. | n.I. | n.I. | n.I. | n.I. | 32 |

| Cadmium | 5 | 79 | 100 | 97 | 60 | 98 | 100 |

| Copper | 0.2 | 85 | 63 | 100 | 50 | 36 | 80 |

| Mercury | 1 | 100 | 74 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 |

| Zinc | 5 | 100 | 99 | 78 (1) | 88 | 100 | 99 (2) |

We can see that neither nitrite nor nitrate inhibits the activities, except for weak inhibitions of AKI by nitrate and threonine synthase (TS) by nitrite. Thus we consider that these compounds will not inhibit the threonine pathway significantly at environmental concentrations. On the other hand, we can see that heavy metals inhibit all enzyme activities; moreover these inhibitions are strong and in some cases total. We decided to study further three of these compounds: cadmium, copper and mercury.

3.2 Kinetic characterisation of the inhibition by heavy metals

Each enzyme activity was measured as a function of the concentration of the three toxic compounds cadmium, copper and mercury, at a constant concentration of substrate. Figs. 2 and 3 give two examples of these measurements. All the enzymes were inhibited by these heavy metals, particularly aspartate semi-aldehyde dehydrogenase (ASD) by cadmium, copper and mercury, TS by copper, AKI and homoserine kinase (HK) by mercury. Mercury is the most potent inhibitor of the whole threonine pathway, though the most sensitive enzyme varies with the metal. The KIs and the Hill coefficients of these inhibitions were determined by fitting the data according to equation (1) and are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Aspartate semi-aldehyde dehydrogenase activity as a function of copper chloride concentration. The activity is measured in the presence of asa 0.2 mM. The curve is drawn according to equation (1) using the corresponding parameters of Tables 2 and 3.

Homoserine kinase activity as a function of the mercury-chloride concentration. The activity is assessed in the presence of hs 1 mM. The curve is drawn according to equation (1) using the corresponding parameters of Tables 2 and 3.

KI (μM) of different heavy metals on enzyme activities and IC50 (μM) of threonine flux

| AKI | AKIII | ASD | HDHI | HK | TS | Threonine Flux | |

| Cadmium | 1946 ± 136 | 112 ± 16 | 18.2 ± 1 | 3350 ± 67 | 675 ± 23 | 122 ± 12 | 69 |

| Copper | 64 ± 2 | 165 ± 11 | 32 ± 2 | 250 ± 17 | 474 ± 22 | 15 ± 2 | 68 |

| Mercury | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 703 ± 40 | 1.33 ± 0.04 | 497 ± 14 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 88.3 ± 5.3 | 2.1 |

Hill number of different heavy metals on enzyme activities

| AKI | AKIII | ASD | HDHI | HK | TS | |

| Cadmium | 1.52 ± 0.14 | 0.79 ± 0.08 | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 1.91 ± 0.07 | 1.67 ± 0.09 | 1.00 ± 0.10 |

| Copper | 1.47 ± 0.07 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 1.49 ± 0.10 | 1.07 ± 0.11 | 1.38 ± 0.12 | 0.99 ± 0.11 |

| Mercury | 2.25 ± 0.13 | 1.74 ± 0.17 | 3.05 ± 0.25 | 1.98 ± 0.11 | 3.59 ± 0.32 | 1.31 ± 0.09 |

3.3 Simulation of the effects of different pollutants

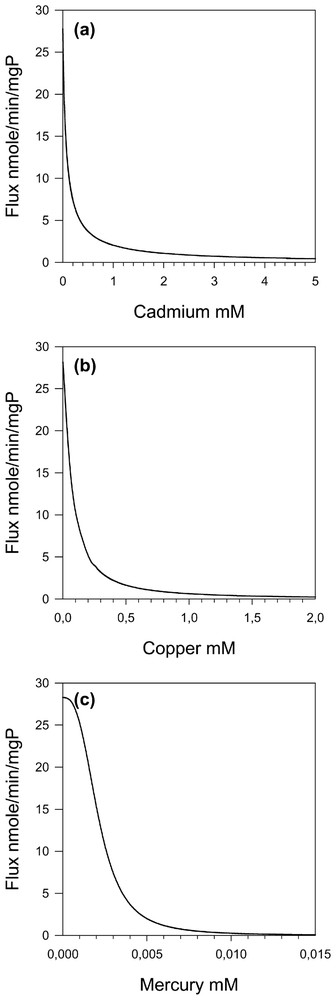

The mathematical model, already developed for threonine pathway [3], has been used to simulate the effects of the different heavy metals (cadmium, copper and mercury) on threonine pathway flux values (Fig. 4). We can see that the IC50 for the whole pathway flux is always larger than the smallest KI for the individual steps (Table 2) by a factor of two to four.

Threonine flux as a function of cadmium (a), copper (b) and mercury (c) concentrations.

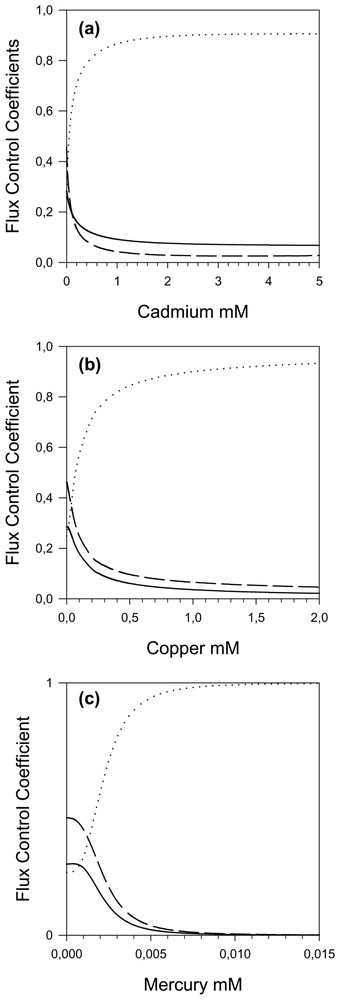

With the model it was also possible to calculate the flux control coefficient distribution between the different steps of the threonine pathway. In the in vivo steady-state conditions, the control is shared between the three first steps 0.282, 0.249 and 0.466, respectively for AK, ASD and HDH. The HK and the TS (respectively 0.005 and 0.000) flux control coefficients can be considered as negligible [3].

By increasing the cadmium concentration, we observe (Fig. 5a) a transfer of the control from AK and HDH to ASD; the control coefficient of ASD reaches a maximum of 0.9 beyond 2 mM. This can be explained by the highest cadmium affinity for ASD. The partial response coefficients (Fig. 6a) emphasize these variations and show a slight increase in the participation of HDH.

Flux control coefficient of the threonine pathway activities as a function of cadmium (a), copper (b) and mercury (c). — AK, ⋯ ASD and – – HDH (the HK and TS flux control coefficients are not represented because their values are always close to zero).

Partial response coefficients of each step as a function of cadmium (a), copper (b) and mercury (c). — AK, ⋯ ASD and – – HDH (the HK and TS partial response coefficients are not represented because their values are always close to zero).

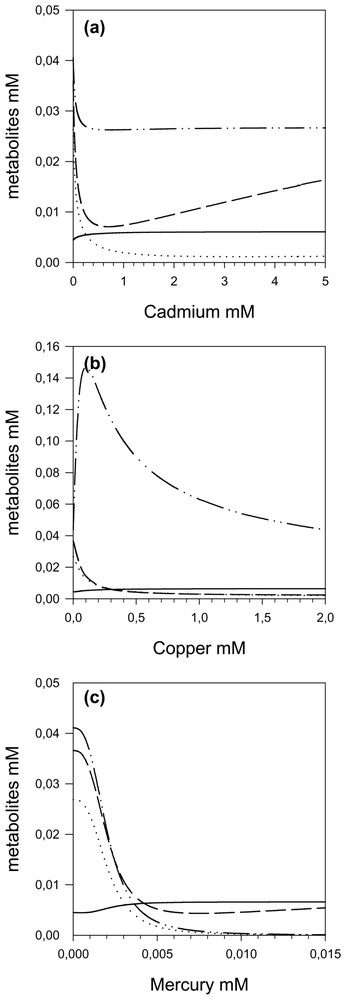

These variations in control are accompanied by an increase in β-aspartyl phosphate (aspp) concentration and a decrease in homoserine (hs) concentrations, due to ASD inhibition. Then hs concentration increases as cadmium concentration, which inhibits HK.

The zero-control coefficient of TS explains why its contribution to flux inhibition (cf. TS partial response coefficient in Fig. 6a) is close to zero, even in a cadmium concentration range inhibiting its activity.

By increasing the copper concentration, we also observe (Fig. 5b) a transfer of the control from AK and HDH to the ASD, which attains a flux control coefficient of nearly 1.0. Thus by increasing the copper concentration, the ASD becomes the only controlling step and the response of the pathway to copper is accounted for, almost entirely, by the response of ASD (Fig. 6b), even though all the enzymes exhibit significant inhibitions (elasticities) with respect to copper throughout the range; as a matter of fact, TS is more inhibited by copper than ASD, but this inhibition has practically no effect on the flux. However, it has an effect on the O-phos-phohomoserine (hsp) concentrations, which first increases (Fig. 7b); the subsequent hsp decrease is due to the flux decrease following ASD inhibition.

Intermediate metabolite concentrations of the threonine pathway as a function of cadmium (a), copper (b) and mercury (c). — aspp, ⋯ asa, – – hs and – ·· – hsp.

When the mercury concentration increases, we once again observe (Fig. 5c) a transfer of the control from AK and HDH to the ASD, up to a maximum of 1 with sigmoid behaviour due to the cooperativity of mercury inhibition. This dominant role of ASD in flux response to mercury inhibition is highlighted in Fig. 6c. As expected, we observe an increase in aspp and a decrease in all other metabolites.

4 Conclusions

All these results show the value of using model for understanding the effects of pollutants such as heavy metals because these compounds could have multiple targets in a metabolic pathway. Indeed, it is not possible to predict the global effect on the flux from the simple consideration of the KI or IC50 values of the individual steps. As a matter of fact, an enzyme modulation can only be transmitted to the whole flux if its control coefficient is appreciable. This is well illustrated by the TS inhibition, which has no effect on the flux due to its zero control coefficient.

Because pollutants affect several steps in the pathway it is also convenient to plot the partial response coefficients (response of the step scaled by the response of the flux), which gives a quantitative measurement of the participation of each step.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank EC for supporting this work through a Copernicus contract No. ERBIC15CT960307.