1 Introduction

The leopard (Panthera pardus) is a carnivore with a long history of conflict with humans in southern Africa [1]. These conflicts represent the nexus of leopard biology and ecology, political and social attitudes, and land and species management practices [2]. Leopards are solitary, highly mobile and extremely adaptable. This assists the species with persisting in agricultural landscapes and near human settlements. Although habitat destruction continues to compromise leopard survival [3], persecution by humans is a major threat, particularly where leopards predate livestock or people. Until recently, leopards were classified as vermin and culled in many regions, with significant numbers also hunted for trophies [4]. This conflict has made effective conservation management of leopards problematic. Although listed as near threatened on the IUCN Red List, persecution has resulted in leopards being locally extirpated from specific localities across southern Africa, where they were formerly widespread [5].

Relatively little is known about leopard behaviour, ecology and genetics at local and regional scales [5], rendering the development and implementation of evidence-based conservation strategies impossible. A typical human response to problem leopards is to extirpate them, but the removal of these top predators can have a cascade effect on populations of prey species and smaller predators [6]. Accordingly, the management of leopard is a contentious topic, as society displays both negative and positive values towards the species. An alternative to extermination or habitat destruction is translocation, which is used by some conservation organisations to resolve conflicts between people and leopard [5]. However, translocation is highly controversial and is not widely endorsed by conservation organisations, largely due to its disputed effectiveness as a technique for managing problem animals and the currently inadequate knowledge of the species and it's impacts on human communities [7]. Few translocation initiatives have conducted the extensive surveys and environmental impact assessments required to provide reliable evidence supporting the effectiveness of translocation as a strategy that ensures the long-term persistence of the leopard population [8,9].

Whilst the removal of problem leopards can initially prove effective, translocating individuals may, if not effectively researched and implemented, simply relocate the problem. Leopards are known to return to home territories following translocation [8], travelling up to 500 km [10], and continue to predate livestock, sometimes in greater numbers, upon their return [8,11,12], exacerbating earlier problems. Alternative strategies to translocation for resolving human–leopard conflicts are numerous [1,13–15] but evaluations of their relative effectiveness are rarely conducted, which perpetuates uncertainty and conflict.

Species management practices can have immense impacts on a populations’ genetic structure, for example, persecution by humans can reduce the size and genetic diversity of a population, whilst re-introductions or translocations can increase genetic diversity [16]. Conservation geneticists generally agree that genetic diversity within and among populations is a prerequisite for the persistence and adaptability of populations [17]. Considering patterns of spatial genetic diversity should therefore be a primary concern for organisations undertaking leopard translocations as the viability of leopard might be compromised [18]. Genetic issues potentially affecting long-term viability and extinction risk include inbreeding depression; declining genetic diversity; mutation accumulation; genetic adaptation to captivity; and outbreeding depression [16].

At the continental scale, the leopard population in southern Africa comprises a single continuous population structured as distinct geographically isolated groups of individuals that display genetic variation across the species’ range [3]. This spatial pattern is likely the product of recent local extirpations and habitat destruction, coupled with their ability to persist across a broad range of habitats and land cover types, and to disperse over long distances [19]. These characteristics, coupled with on-going translocations, ensure that maintaining the natural genetic structure and diversity of the southern African leopard population is a major conservation management challenge.

No guidelines currently exist for maintaining the natural genetic structure and diversity of the southern African leopard population [20]. Motivated by the plight of leopards [9] and recognizing the importance of understanding natural genetic processes for ensuring their persistence, we aimed to:

- • use mitochondrial and microsatellite markers to describe the spatial genetic structure of the southern African leopard population;

- • map the regional scale genetic diversity in southern Africa;

- • estimate a maximum translocation distance for leopard in the Eastern and Western Cape provinces of South Africa to assist organisations translocating problem leopards.

Our results suggest that genetic information should inform policy development and management decisions, notably the translocation of problem leopards.

2 Methods

2.1 Taxonomic samples

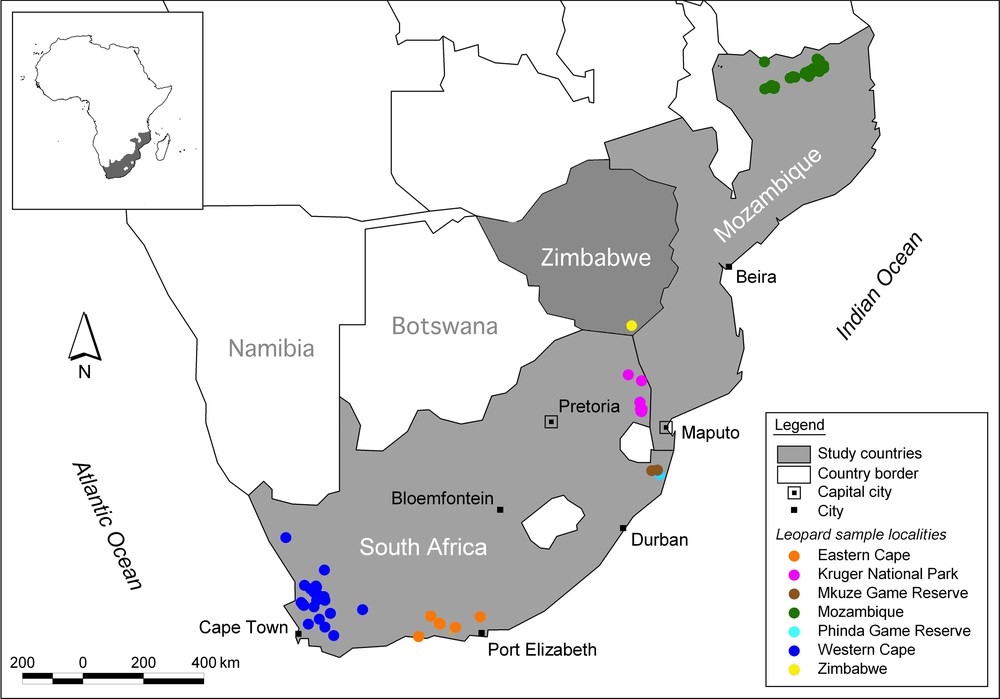

A total of 145 leopard (P. pardus) samples of known origin were collected between 1998 and 2008 with the assistance of CapeNature, the Cape Leopard Trust, Panthera and the Niassa Carnivore Project, from seven large geographic areas across southern Africa. The Western Cape province provided 32 samples; 18 individuals were sampled adjacent to the Kruger National Park; 18 and 30 samples originated, respectively, from the Mkuze Game Reserve and the Phinda Private Game Reserve in the KwaZulu-Natal province; 11 were sampled from the Baviaanskloof World Heritage Site (WHS) in the Eastern Cape province; 35 samples were obtained from the Niassa province in Mozambique; and one sample was obtained from southern Zimbabwe (Fig. 1). DNA was extracted from skin biopsies, hair, dry skin and muscle using a DNeasy Blood and tissue kit (Qiagen).

(Colour online.) The location of the 145 samples assessed for possible inclusion in the analysis of translocation distances for southern African leopards (Panthera pardus).

2.2 mtDNA analyses

Two mitochondrial genes were successfully amplified for 137 individuals, the cytochrome b gene (Cyb) and the NADH dehydrogenase 5 (NADH-5) (accession numbers: JF720057–JF720319). Two sets of primers were used: leo-F: GACYAATGATATGAAAAACCATCGTTG/Leo-R: GTTCTCCTTTTTTGGTTTACAAGAC for Cyb amplification, and F/RL2 for NADH-5 [3]. Amplifications were performed in 50 μL under the following conditions: 5 μL of 10× buffer with MgCl2, 5 μL (6.6 mM) of dNTP, 0.3 μL (2.5 U) of Taq DNA polymerase (Southern Cross Biotech), and 2.5 μL of primers at 10 μM. PCR conditions were as follows: 3 min at 94 °C; 35 cycles of denaturation/annealing/extension with 30 s at 94 °C for denaturation, 1.5 min at 55 °C (NADH-5) 50 °C (Cyb) for annealing, and 1 min at 72 °C for extension; and 7 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were sequenced in both forward and reverse directions on an ABI 3730 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems). One hundred and thirty-seven out of the 145 leopards sampled were used in the final analysis. Amplification and sequencing was unsuccessful for eight samples (including Zimbabwe) due to DNA degradation caused by ineffective preservation.

Mitochondrial sequences were edited using Sequencher 4.9 (Gene Codes Co., Ann Arbor, Michigan) and a consensus was generated from the two sequences (forward and reverse) that were obtained for each PCR fragment. Nucleotide sequences were aligned manually with Sequence Alignment Editor Version 2.0 alpha 11 (Andrew Rambaut, software available at http://evolve.zoo.ox.ac.uk/). The protein-coding genes (NADH-5, Cyb) were aligned using the amino-acid sequences. The matrix was trimmed to exclude missing data at the ends and comprised 611 nt for NADH-5 and 1126 nt for Cyb. The sequenced regions corresponded, respectively, to positions 12632–13242 and 15046–16171 in the complete Felis catus mtDNA genome (accession number U20753). P. pardus fusca (EF199743 and EF199742) sequences were used as outgroup. The total matrix represents 1737 characters and 28 mitotypes (mitochondrial haplotypes).

A minimum spanning haplotype network was constructed using PopART 1.7 (Jessica Leigh, software available http://popart.otago.ac.nz).

Parsimony analyses were conducted with PAUP 4.0b10 [21] using the tree bisection–reconnection branch swapping algorithm. Branch support was determined using bootstrap percentages (BPs) computed after 100 replicates under the closest stepwise addition option.

Bayesian inference (BI) was also used for phylogenetic analyses. The two genes were concatenated for the analysis and the appropriate model was applied to each partition. Bayesian analyses were performed with MrBayes 3.1.2 [22]. For each gene, MrModeltest 2.2 [23] was used to determine the prior model of DNA substitution (HKY + G for NADH-5, GTR + G + I for Cyb, K80 + I for the first position of Cyb, GTR for the second position of Cyb, GTR + G for the third position of Cyb, and HKY for each position of NADH-5) using the Akaike Information Criterion. Two different analyses were performed, the first with the appropriate model applied to each locus, and the second to the appropriate model applied to each codon position. Analyses were conducted with five independent Markov chains run for 2,000,000 Metropolis-coupled Monte Carlo Markov chain (MCMC) generations, with tree sampling every 100 generations, and a burn-in period of 2000 trees. MrBayes performs two separate analyses by default, and we used the plot option to check for the convergence of the parameters. Posterior probabilities (PP) were obtained for each node.

2.3 Nuclear DNA analyses

Leopard samples were analysed using eight polymorphic microsatellite loci, isolated from the domestic cat, F. catus [24]. The selected loci (FCA008, FCA026, FCA043, FCA077, FCA211, FCA220, FCA247, FCA453) were previously used for a phylogeographic study of leopards [3] and were shown to be polymorphic in leopards and other non-domestic cat species [25,26]. PCR amplifications were performed using the Multiplex PCR Kit (QIAGEN) following the recommended protocol using Q-Solution in a final reaction volume of 10 μL (5 μL of 2× QIAGEN Multiplex Master Mix), 1 μL of primer mix (mix of forward and reverse primers) (2 μM), 1 μL of Q-solution, 1 μL of H2O and 2 μL of template DNA). PCR conditions were standard and annealing occurred at 60 °C. Primers were in multiplex reactions: (i) FCA008, FCA026, FCA043, FCA211; (ii) FCA077, FCA220, FCA247, FCA453. Genotyping was performed on an ABI 3730 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Alleles scoring was done using Genemapper 3.7 software (Applied Biosystems) and double-checked by eye. A total of 145 samples were successfully genotyped and less than 2% of alleles were missing in the final dataset. Analyses were implemented in MICROCHECKER 2.2.3 [27] to check the quality (presence of null alleles, allelic dropout, stuttering) of the dataset. Null alleles may be present for FCA008 and FCA077, but with frequencies lower than 10% in the whole dataset and lower than 5% within geographic groups.

Population genetics indexes (HE, HO, FIS) were calculated for each geographic region using GENALEX 6 [28] with the exception of Zimbabwe, which comprised only one individual. Pairwise FST values were computed and tested using permutations tests (1000) implemented in FSTAT [29]. Tests for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium within each population were performed using Genepop’007 [30].

A Bayesian model executed in a MCMC using the R-package GENELAND version 3.1.5 [31,32] to detect the location of genetic discontinuities using individual geo-referenced multilocus genotypes [33]. This model treats the number of clusters as a parameter processed by the MCMC scheme without any approximation and may provide a more precise estimation of the number of clusters than alternative techniques that do not account for geographical location [33,34]. Ten independent runs of the GENELAND model were performed with 5,000,000 iterations, of which every 100th iteration was saved, treating the number of genetic clusters as unknown and using the spatial D-model as a prior model for allele frequencies (assumed to be independent). GENELAND uses geographic locations of individuals as prior information. A second Bayesian approach to estimate clustering was tested using STRUCTURE 2.3.3 [35]. This method assigns individual multilocus genotypes probabilistically to a user-defined number (K) of clusters (or gene pools), in order to approach linkage equilibrium within clusters. We ran STRUCTURE 10 times for each K = 1–10, for 1,000,000 iterations after a burn-in period of 1,000,000 on the data set with no earlier information on the population of origin of individual leopards. We used the admixture model, in which the fraction of ancestry from each cluster was estimated for individual leopards. The same parameter of individual admixture (α) was chosen for all clusters and was given a uniform prior. The allele frequencies were kept independent among clusters to avoid overestimating the number of clusters [36]. We followed the procedure of Evanno et al. [37] to infer the number of clusters detected in the dataset. Finally, correspondence analyses were performed to display the distribution of the genetic diversity using Genetix 4.0.5 [38].

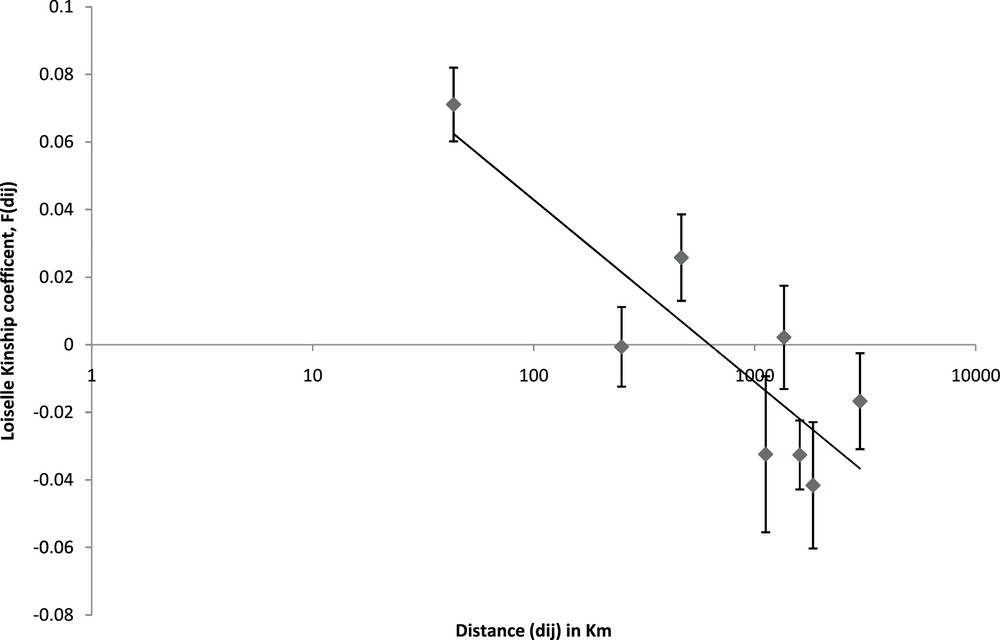

Spatial autocorrelation analyses were performed to test the presence of a spatial genetic structure (SGS) due to an isolation-by-distance (IBD) process. We assessed the SGS using the method of Vekemans and Hardy [39], based on pairwise kinship coefficients between individuals using the software SPAGeDi 1.3 [40]. The kinship coefficient [41] was chosen as the pairwise estimator of genetic relatedness, as it is a relatively unbiased estimator with low sampling variance. Kinship coefficient values (Fij) were also regressed on dij, where dij is the natural logarithm of the spatial distance between individuals i and j, to provide regression slope bd. To visualize SGS, the kinship coefficient values were averaged over a set of distance classes (d), giving F(d), and plotted against the geographic distance. Standard errors were assessed by jackknifing data for each locus. To test for SGS, spatial positions of individuals were permuted 9999 times in order to obtain the frequency distribution of the slope bd under the null hypothesis that Fij was not correlated with dij.

2.4 Estimation of gene dispersal

In presence of IBD process, Wright's neighbourhood size, Nb = 4 Deσ2, where De is the effective density and σ2 is the mean squared axial parent–offspring distance, can be estimated as Nb = –(1 – FN)/bd when the regression slope bd is computed within the distance range σ > dij > 20 σ [40]. As σ is unknown, an iterative approach, implemented in the SPAGeDi 1.3 software [40], was applied to jointly estimate Nb and σDe. We applied this approach collectively to leopards only from the Eastern Cape and Western Cape provinces, due to the greater availability and accuracy of the spatial location, home range and species density information. In this region, leopards mostly occur in mountainous areas at an estimated density of approximately three individuals per 100 km2 [42]. As estimating effective population density (De) from D is problematic, we applied the precautionary principle and used De = D/2 and D/10 as boundary values for De, D/10 being a highly conservative estimate of De [43,44].

3 Results

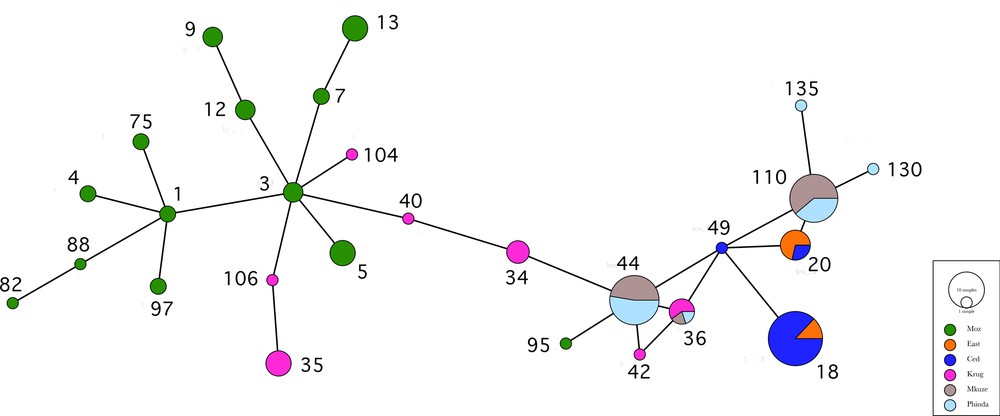

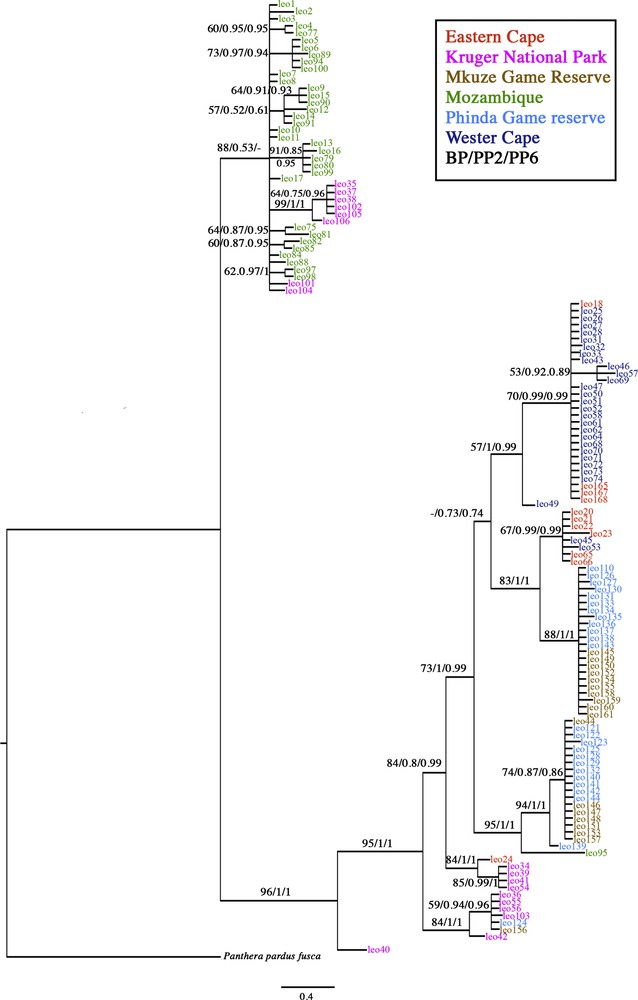

Minimum spanning network, Bayesian and parsimony analyses performed on the two mtDNA markers demonstrate spatial structure (Fig. 2-3). The mtDNA tree reflects the structure of the female leopard population. None of the localities were found to be monophyletic in either the mitochondrial bootstrap tree or the Bayesian tree (Fig. 3). With the exception of individual leo95, leopards from Mozambique grouped together in a clade (BP = 71/–/PP6 = 1) that included two individuals adjacent to the Kruger National Park (leo104, leo101). The Western Cape individuals were distributed across two clades (BP = 57/PP2 = 1/PP6 = 0.99; BP = 67/PP2 = 0.99/PP6 = 0.99) including one Eastern Cape individual. Phinda and Mkuze individuals were related and are distributed across two clades (BP = 88/PP2 = 1/PP6 = 1; BP = 94/PP2 = 1/PP6 = 1) with the exception of individuals leo124 from Phinda and leo156 from Mkuze, that were clustered in a clade with Kruger individuals (BP = 84/PP2 = 1/PP6 = 1).

(Colour online.) Minimum spanning network among the mitochondrial haplotypes performed under PopART 1.7. The size of the circle is proportional to the frequency of the haplotype in the total population.

Bayesian tree reconstructed form the concatenated dataset combining Cyb and NADH-5 with two partitions HKY + G for NADH-5, GTR + G + I for Cyb using MrBayes 3.1.2 (only nodes with PP > 0.5 are represented). The three values on each node correspond to: (1) the BP value; (2) the PP of the Bayesian analysis run with two partitions, and (3) the PP of the Bayesian analysis run with six partitions. A dash indicates that nodes were not found in the analysis but without any supported alternative. Samples are colour coded as follows: Cape Province = dark blue; Kruger National Park = pink; Mkuze Game Reserve = light brown; Phinda Private Game Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal province = blue pale; Baviaanskloof World Heritage Site (WHS) in the Eastern Cape Province = orange; Niassa province of Mozambique = green. For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure caption, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Microsatellite genotypes revealed a relatively high genetic diversity with the expected heterozygosity (HE) ranging between 0.65 for the Mkuze area of KwaZulu-Natal to 0.74 for individuals sampled adjacent to the Kruger National Park (Table 1). Inbreeding indices (FIS) were relatively low and ranged from 0.04 in Mkuze to 0.11 in the Baviaanskloof WHS which straddles the Eastern Cape and the Western Cape provinces, suggesting minimal vulnerability from small population size, inbreeding depression or mating strategies. The global FST value was 0.09 and pairwise FST values were relatively low but significant, with a maximum value of 0.16 between the Cederberg and Mkuze populations (Table 2).

Population genetics indices.

| n | HO/HE | F IS | A | |

| Western Cape | 32 | 0.624/0.686* | 0.11 | 4.86 |

| Eastern Cape | 11 | 0.646/0.686NS | 0.11 | 4.93 |

| Kruger | 18 | 0.700/0.743* | 0.09 | 5.64 |

| Mkuze | 19 | 0.638/0.647NS | 0.04 | 4.28 |

| Mozambique | 35 | 0.687/0.730* | 0.07 | 5.99 |

| Phinda | 30 | 0.660/0.694* | 0.07 | 4.80 |

* P value < 0.05; NS: not significant.

Pairwise FST values. Most values are relatively low but significant. Highest values are associated with the Mkuze-Phinda populations.

| Western Cape | Eastern Cape | Kruger | Mkuze | Mozambique | Phinda | |

| Western Cape | 0.022 | 0.071 | 0.157 | 0.094 | 0.121 | |

| Eastern Cape | * | 0.046 | 0.130 | 0.083 | 0.110 | |

| Kruger | * | * | 0.083 | 0.045 | 0.075 | |

| Mkuze | * | * | * | 0.130 | 0.055 | |

| Mozambique | * | * | * | * | 0.120 | |

| Phinda | * | * | * | * | * |

* P value < 0.05 after 1000 permutations.

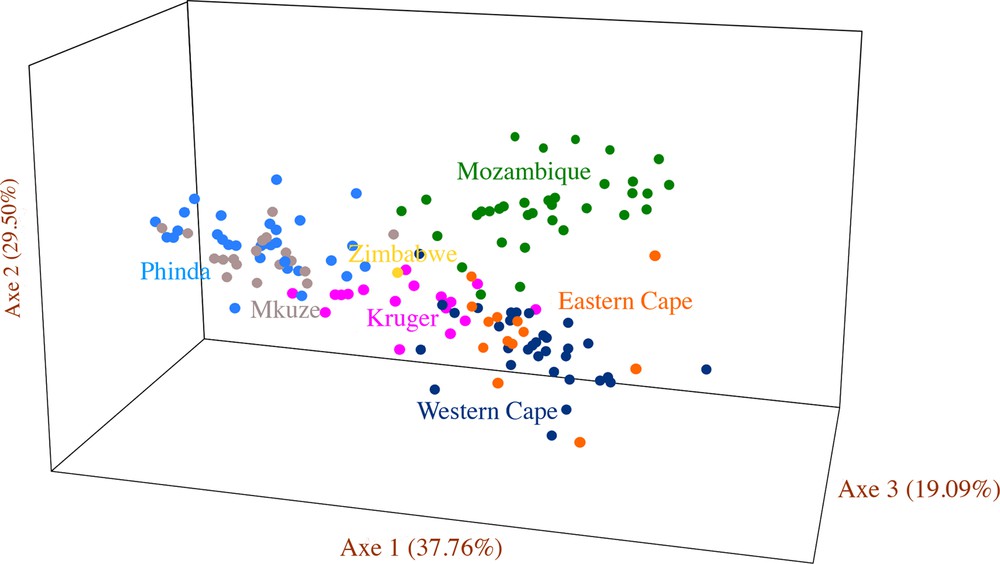

No significant genetic discontinuities were found using Bayesian clustering approaches for the microsatellites data. No consensus on the number of clusters and their spatial distribution were found among runs despite convergences in MCMC being achieved with GENELAND. Results were strongly divergent among runs with best-fitted K-values ranging from 8 to 20, with no apparent spatial structure regardless of the K-value used. Results from the algorithm implemented in STRUCTURE [35] and compiled following Evanno et al. [37] indicated that K = 2 would be the best-fitted K-value. This produced two distinct genetic clusters: the Mkuze-Phinda individuals and all remaining individuals. However, this analysis does not account for the possibility that K = 1 is the best-fitted K-value. Both GENELAND and the multivariate analysis suggested the dataset comprises a single gene pool. The factorial correspondence analysis performed on the microsatellites marker data (Fig. 4) did not locate discrete gene pools within the dataset but showed that Kruger leopards have a central position, which can be explained by their geographic location relative to other individuals.

Spatial representation of individuals by Factorial Correspondence Analysis performed on microsatellites data to test the possible admixtures that occurred between the geographic groups using the module “AFC sur populations” of the GENETIX software. Colours correspond to the geographic groups in Figs. 1 and 2. For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure caption, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

Spatial autocorrelation analyses [40] were used to test for the presence of a SGS due to IBD [45] and found a significant correlation between the kinship coefficient (F(dij)) [41] and spatial distance of individuals (slope = –0.02; P value = 0.00), indicating a dominant role for IBD in shaping the geographic distribution of genetic diversity in southern African leopards (Fig. 5). The collective effective gene dispersal (σ) index [40] for individuals from the Eastern and Western Cape provinces ranged from 24 km (De = D/2) to 82 km (De = D/10).

Average kinship coefficient (dij), plotted against geographic distance (F(dij)) between individual leopards. Standard errors were assessed by jackknifing data over each locus.

4 Discussion

This study represents the most comprehensive analysis of the SGS of southern African leopard. It confirmed that southern African leopards comprise a single population of distinct geographically isolated groups [3]. IBD is the natural process shaping the spatial distribution of genetic diversity in the southern African leopard population. As the leopard population currently displays a healthy genetic structure, translocations justified on the grounds of improving genetic diversity are erroneous. In the context of IBD, the effective gene dispersal (σ) index can be used to estimate translocation distances for southern African leopards.

The translocation of carnivores is not primarily undertaken by conservation organisations to ensure persistence of a species, but rather to immediately and directly reduce human–carnivore conflict. In the case of southern African leopards, land managers view the species as the cause of conflict (i.e. leopards predate domestic stock), and so land managers exterminate them. To avoid local extinctions, conservation organisations understandably react by removing the perceived cause of the conflict (i.e. individual leopards). Our finding from the STRUCTURE analysis of the segregation of the Mkuze-Phinda population could reflect local exterminations (almost 40%) through severe persecution by humans resulting in a strong impact on alleles frequencies [46].

Analysis of genetic data alone will not provide an ultimate enduring solution to human–leopard conflict. Human–leopard conflict is a highly complex problem, comprising a diverse array of interacting factors that exhibit non-linear relationships, meaning solutions to human–leopard conflict will require multiple types of knowledge, and should avoid pursuit of panaceas (such as, translocation), which are rarely effective [47]. In this context, we identify three matters conservation managers should consider when contemplating leopard translocations.

Firstly, and most immediately, translocation of leopards is best avoided. In the Eastern and Western Cape provinces, where the greatest number of samples and leopard density data was available, a highly conservative value of σ was estimated (by applying De = D/10). As the genetic diversity indexes indicate no inbreeding depression, long-distance translocations (i.e., those greater than σ) may strongly counter the natural processes responsible for the IBD structure of southern African leopards. Accordingly, individual leopards should not be translocated more than 82 km from the centre of their home range if natural SGS is to be maintained. Given the highly conservative estimate of De, translocations, if absolutely necessary, should be conducted over significantly shorter distances. The two mtDNA markers, which reflect the structure of the female leopard population, display substantial spatial structure (Fig. 2-3), a result that supports previous findings that female leopards are less mobile than males, or are less frequently translocated [48].

Secondly, whilst the adoption of an evidence-based approach to leopard conservation is prudent [49], the absence of not only genetic information, but more generally of leopard biology and ecology, prevents such an approach. Our investigation revealed little data on the presence and abundance of leopards in different regions, or the effects of translocation on individual leopards. Strategic research into the biology and ecology of the southern African leopard is required to ensure evidence-based decisions making. However, human–leopard conflict is also an incompatibility of interest between leopards and people. Recent research has highlighted the importance of human tolerance towards mitigating human–wildlife conflict [6]. Little research has been conducted into this, and other, human dimensions of human–leopard conflict. An understanding of the differing attitudes, behaviours, and feasibility and acceptability of alternative management strategies of all stakeholders will be required. Translocations uninformed by scientific evidence may create unintended problems by relocating leopards into areas with insufficient prey or available mates, or home ranges occupied by other individuals or areas where less-tolerant land managers reside. Given the considerable uncertainty surrounding the ecological and human dimensions impacting the persistence of leopards, it will be wiser to avoid disturbing the natural spatial genetic structure than to perform translocations oblivious to the potential consequences [16,50].

Thirdly, the findings of our genetic analyses, the extensive distribution of the southern African leopard population and the implications of human–leopard conflict demand a centrally co-ordinated, continent-wide collaborative conservation planning policy [6]. This will require the support of spatially explicit analyses, as conservation problems stem from the geographic relationship between people, ecosystems and species [51]. This could begin with a centralised database of spatial and temporal locations of known leopards and translocations. The implementation of a continental policy on the translocation of leopards could follow the collection of abundance, distribution and translocation data so as to calculate maximum translocation distances in specific regions of known intense human–leopard conflict. The development of leopard conservation policy could then be guided by sub-continental spatial analyses of conservation opportunity [52] incorporating genetic, biological, ecological, human, social, threat and management data [53]. Integrating approaches employed in others parts of the world for the spatial design of conservation corridors for top carnivores (e.g., [54]), and the incorporation of genetic data into spatial prioritisation analyses will also likely prove useful. If these types of analyses are to bridge the gap between research and action (see [55]) and deliver long-term, sustainable solutions they will be required to indicate where and how a diverse, targeted mix of complementary conservation instruments can be delivered most cost-efficiently [56]. Education and incentive programmes for land managers that proactively aim to improve human tolerance of leopard will be essential. Alternatives to translocation, such as the use of livestock collars, strategic fence placement, shepherds and dogs, should be trialled, as they have proven effective in some cases [14,57,58]. Bringing together land managers, government officials, conservation organisations and researchers in a context of trust, coupled with sufficient funding, an optimal mix of complementary conservation instruments, and informed by a robust understanding of both the limited distance over which leopard can be translocated and the factors determining land managers’ tolerance, will provide the foundation for an evidence-based conservation strategy for southern African leopard.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

The Cape Leopard Trust, Landmark Foundation and Panthera provided genetic samples. AR was funded by the Claude-Leon Foundation. CB was the beneficiary of a post-doctoral grant from the AXA Research Fund. The Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions (CEED) at The University of Queensland supported ATK. NRF and the Cape Leopard Trust provided a research grant to CM. CapeNature provided support in collecting samples and Colleen and Keith Begg from the Niassa Carnivore Project, in collaboration with SRN (Niassa Reserve) provided samples from Mozambique. Ruth Kansky is thanked for alerting us to the importance of tolerance in human–wildlife conflict.