1 Introduction

As outlined in previous papers [1–3], the large majority of the scorpion genera represented in Madagascar are endemic and in most cases representing very ancient lineages. The genus Neogrosphus Lourenço, 1995 was created for the species Grosphus griveaudi Vachon, 1969 (Fig. 1) [4], which was described based on five males and two females collected in dry southwestern vegetation formations at two sites in the ex-Province de Toliara: Tanandava in the Mikea Forest, east of Lake Ihotry and north of Toliara and Evazy, S of Toliara (Fig. 2, map, right). According to Vachon [5], the specimens from Tanandava were found in a baobab (Adansonia) forest on red sands, and those from Evazy in the spiny bush biome composed of Didiereaceae and Euphorbiaceae.

Neogrosphus griveaudi, female paratype from Tanandava. Habitus.

After Vachon, 1969.

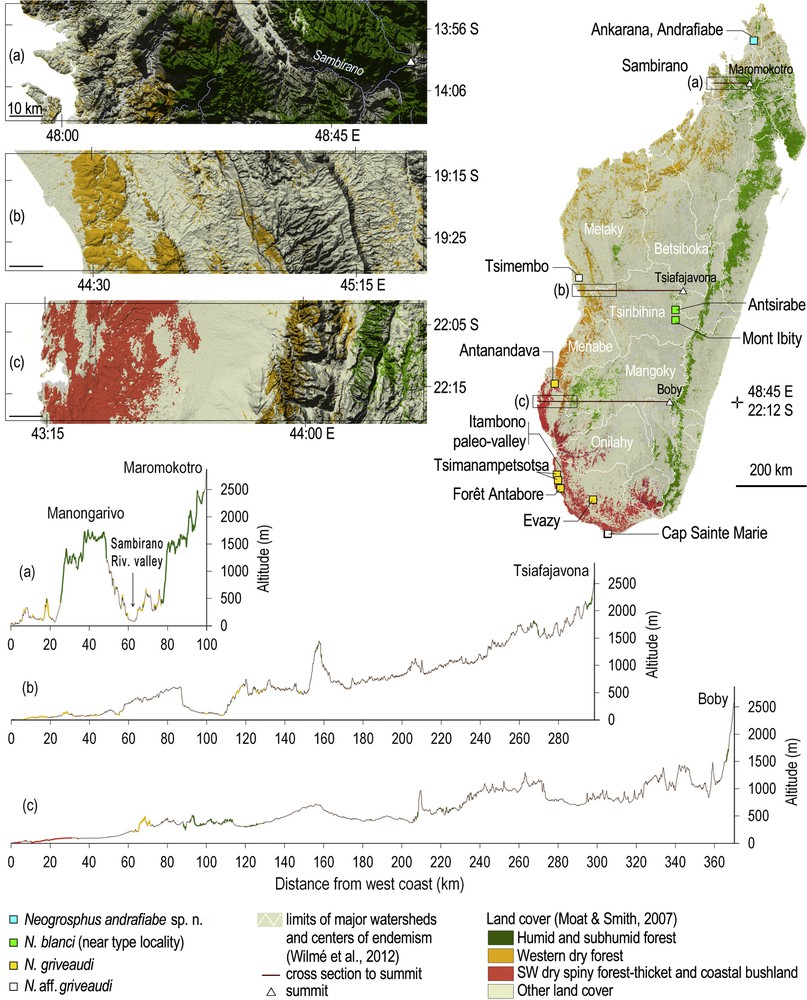

(Colour online.) Collection localities of Neogrosphus andrafiabe sp. n., Neogrosphus blanci, Neogrosphus griveaudi, and species in the genus Grosphus with identification to be confirmed, according to land cover (top right). Insets of the coastal areas to the west of the three highest summits (top left), and cross section from west coast to the three highest summits, underlying the rugged topography of the Sambirano (bottom).

The creation of the new genus Neogrosphus [4] was decided to accommodate the species G. griveaudi that showed a range of morphological characters falling outside of typical members of the genus Grosphus. In the original description of G. griveaudi [5], it was already obvious that the generic position of this species was questioned, and Vachon [5] stated as follows on page 481: “La détermination des spécimens qui ont permis la création de cette espèce nouvelle nous a posé maints problèmes… Il est donc fort possible que l’espèce griveaudi appartienne à un sous-genre nouveau ou à un genre nouveau.”

One year after the description of the genus Neogrosphus [4], a second species, Neogrosphus blanci Lourenço, 1996 was described based on one male specimen held in the collections of the Muséum in Paris. This new species was a priori considered as collected from an imprecise locality in Central Madagascar [1,6]. However, more recent data brings further details about its possible type locality (see the section on N. blanci).

In a paper by Lourenço et al. [6], a preliminary synthesis was proposed for the known elements of the genus Neogrosphus. This was based on extensive samples of new material of this group collected during considerable biological exploration performed for more than a decade. For details on this material, refer to Lourenço et al. [6].

The present study of one new specimen of Neogrosphus has resulted in the discovery of one new species. The type material has been collected from the Ankarana Massif in extreme North of Madagascar, and is partially related to N. griveaudi, which has a range of distribution limited to the south and southwestern regions of Madagascar. This represents yet a new case of disrupted distribution, which illustrates one more example of micro-endemism and vicariance among the populations of Malagasy scorpions.

2 Methods

Illustrations and measurements were made with the aid of a Wild M5 stereomicroscope, equipped with a drawing tube (camera lucida) and an ocular micrometer. Measurements follow Stahnke [7] and are given in mm. Trichobothrial notations follow Vachon [8], while morphological terminology mostly follows Vachon [9] and Hjelle [10].

3 Taxonomic treatment

Family BUTHIDAE C.L. Koch, 1837

Genus Neogrosphus Lourenço, 1995

Diagnosis for the genus Neogrosphus

Scorpions of average size when compared with most species of Malagasy buthids. Males much smaller than females measuring from 24 to 30 mm in total length, whereas females may reach up to 45 mm [6]. General coloration pale yellow to reddish-yellow with or without dark spots over the body and appendages. Disposition of granulations on the dentate margins of the pedipalp chela fingers, arranged in 8 to 9 rows of granules. Subaculear tooth absent both in adults and juvenile forms. Trichobothriotaxie type A with A-α (alpha) disposition for the dorsal trichobothria of femur [8,11].

The known species of Neogrosphus

Neogrosphus griveaudi (Vachon, 1969) (Fig. 1)

Same diagnosis as for the genus. General pattern of pigmentation yellowish, with dark spots over the body and appendages. Carapace yellowish with an inverted dark triangle extending from the anterior edge to the zone behind the median eyes. Tergites with confluent dark zones, less marked on tergite VII. Metasomal segments I to V with the anterior half marked by a dark ring. Telson yellowish without spots. Pedipalps yellowish; femur and patella with spots on the internal and external faces; chela and chelicera without spots. Legs with spots only in the anterior segments. Pectinal teeth count: 27 to 29 for females and 29 to 31 for males. For ecology, refer to Lourenço et al. [6].

Neogrosphus blanci Lourenço, 1996

Same diagnosis as for the genus. General pattern of pigmentation yellowish to reddish-yellow without any spots over the body and appendages. Pectinal teeth count: 27–27 in male. Female unknown. This species was originally described from an imprecise locality. In the previous synopsis of the genus Neogrosphus [6], it was suggested that it was possibly collected in the region of Isalo. More accurate investigation shows, however, that this statement was wrong. In the registration books of the Muséum in Paris, we found data confirming that N. blanci was collected together with specimens of Grosphus limbatus (Pocock, 1889) in the Central Massifs of the island, probably between Ibity and Antsirabe, by Jacques de Saint-Ours back in the 1960s. Consequently, even if nothing is known about the ecology of this species, its habitat is probably similar to that of G. limbatus.

Neogrosphus andrafiabe sp. n. (Figs. 3–4)

Neogrosphus griveaudi, male from Efoetse (A) and Neogrosphus andrafiabe sp. n., male holotype. (B–D). A–B. Carapaces showing the distinct patterns of pigmentation. C. Tergite VII and metasomal segment I, with pigmentation pattern. D. Metasomal segment V and telson, lateral aspect, with pigmentation pattern.

Neogrosphus andrafiabe sp. n., male holotype. A–B. Right pedipalp, dorsal aspect, showing pigmentation and trichobothrial patterns. C. Cutting edge of movable finger with rows of granules.

Material examined: Male holotype. Madagascar, ex-Province d’Antsiranana, Région DINA, Massif de l’Ankarana, P. N. Ankarana, in the area of Andrafiabe cave (local people to W.R. Lourenço), IX/2001, (collected together with a female specimen of Grosphus sp., which will be correctly defined in a subsequent study). Holotype deposited in the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris.

Etymology: The specific name is a noun in apposition to the generic name and refers to the area where the new species was found.

Diagnosis: Scorpions of average size when compared with the other two species of the genus. Male with 27.8 mm in total length. General coloration pale yellow to yellow with brownish spots over the body and appendages. Disposition of granulations on the dentate margins of the pedipalp chela fingers, arranged in 8 rows of granules. Subaculear tooth absent. Pectines with 27–28 teeth. Trichobothriotaxie type A with A-α (alpha) disposition for the dorsal trichobothria of femur [8,11].

Relationships: The general morphology and pigmentation pattern of the new species shows it to be closer to N. griveaudi than to N. blanci. This last species totally lacks spots. The two known species are distributed in the southwestern and Central regions of Madagascar (see biogeographic section). The new species can be readily distinguished by the following characters:

- • distinct pigmentation pattern; anterior triangle on carapace only vestigial; tergites IV to VII with better marked spots; pedipalps and legs with only vestigial spots;

- • male pectines with 27–28 teeth vs. 29 to 31 in G. griveaudi;

- • cutting edges of pedipalp fingers with 8–8 rows of granules vs. 8–9 in N. griveaudi.

4 Taxonomic comments

In the previous synopsis on Neogrosphus [6] it was suggested that the observed variation in the pigmentation pattern of some specimens from Cap Sainte Marie, could be attributed to polymorphism. Also, the only examined specimen from the “Forêt de Tsimembo” was poorly preserved and could constitute a distinct taxon. Only the study of further specimens from these localities will precisely allow defining the status of these potentially distinct populations.

Description based on male holotype. Morphometric values following the description.

Coloration. General pattern of pigmentation yellowish, with dark spots over the body and appendages. Carapace yellow with an incomplete inverted dark triangle extending from the lateral eyes to the zone behind the median eyes; eyes surrounded by black pigment. Chelicerae yellow without any variegated pigmentation; fingers with reddish teeth. Mesosoma yellow; all tergites with strongly marked confluent dark zones. Venter: coxapophysis, sternum, genital operculum pectines and sternites pale yellow. Metasomal segments I to V with the anterior half marked by a dark ring. Telson yellow without spots; tip of aculeus reddish. Pedipalps yellow; femur and patella with spots on the internal and external faces, weakly marked; chela yellow without spots; rows of granules on fingers reddish. Legs with only vestigial spots in the anterior segments.

Morphology. Carapace weakly to moderately granular; anterior margin with a weak median concavity. Carinae absent; furrows weakly developed. Median ocular tubercle anterior to the centre of the carapace; median eyes separated by one ocular diameter. Three pairs of lateral eyes. Sternum subtriangular in shape. Mesosomal tergites with thin but intense granulations. Median carina moderately to weakly marked in all tergites. Tergite VII pentacarinate. Venter: genital operculum consisting of two subtriangular plates. Pectinal teeth count 27–28; basal middle lamellae of each pecten not dilated. Sternites smooth, with moderately elongated stigmata; VII without carinae. Metasomal segments I and II with 10 carinae, moderately crenulate. Segments III and IV with 8 carinae, moderately crenulate. Segment V with 3 carinae, rounded and smooth dorsally. Dorsal carinae on all segments without any posterior spinoid granules. Intercarinal spaces with some thin granulation, almost smooth. Telson smooth; aculeus weakly curved and shorter than the vesicle; subaculear tooth absent. Cheliceral dentition characteristic of the family Buthidae [12]; two distinct but reduced basal teeth present on the movable finger; ventral aspect of both fingers and of manus with dense, long setae. Pedipalps: femur pentacarinate with weakly marked carinae; patella with dorsointernal and ventrointernal carinae without any spinoid granules on the internal face; chela without carinae, smooth. Fixed and movable fingers with 8–8 oblique rows of granules. Trichobothriotaxy; orthobothriotaxy A-α (alpha) [8,11]. Legs: tarsus with numerous short thin setae ventrally. Tibial spurs present on legs III and IV, thin and long; pedal spurs present on legs I to IV, moderately marked. Female unknown.

Morphometric values (in mm) of the male holotype of N. andrafiabe sp. n. Total length (including telson), 27.8. Carapace: length, 2.9; anterior width, 1.8; posterior width, 2.8. Mesosoma length, 7.5. Metasomal segments. I: length, 2.3; width, 1.7; II: length, 2.6; width, 1.5; III: length, 2.7; width, 1.5; IV: length, 3.2; width, 1.2; V: length, 3.7; width, 1.2; depth, 1.2. Telson length, 2.9. Vesicle: width, 0.7; depth, 0.9. Pedipalp: femur length, 1.9, width, 0.8; patella length, 2.4, width, 1.0; chela length, 3.3, width, 0.9, depth, 0.8; movable finger length, 2.1. Some comparative morphometric values for the male holotype and female paratype of N. griveaudi and male holotype of N. blanci. Carapace: length, 4.0/5.4/2.7. Metasomal segments. I: length, 2.5/4.2/1.6; V: length, 4.8/7.3/3.1.

5 Biogeographic comments

N. blanci is only known from the type locality on the highlands near Antsirabe or Mont Ibity, in the upper Tsiribihina watershed (Fig. 2 map, right) [13]. Numerous inselbergs are found on these highlands. Those encountered near Mont Ibity culminating at 2254 m are characterized by several narrow endemic species of plants, as the small trees Pentachlaena latifolia H. Perrier or Abrahamia ibityensis (H. Perrier) and dominated by the pyrophytic tapia tree Uapaca bojeri Baill [14].

N. griveaudi is mostly encountered in southwestern dry spiny forest-thicket and coastal bushland, which are the types of forest occurring in the subarid region of the island where annual rainfall can be less than 500 mm [15] (Fig. 2, map, right). The collection from the dry forest of Tsimembo is of a poorly preserved specimen, which has not been re-located for the present study. N. griveaudi has not been recorded from the Central Menabe between the Mangoky and Tsiribihina watersheds, nor in other western dry forests to the north and northeast of Tsimembo (Fig. 2, map, right). The Tsimembo forest lies in the southern portion of the Melaky center of endemism, sensu Wilmé et al. [13], and is characterized by several large lakes to the northeast and to the south of the forest. The collection locality of N. griveaudi in the Tsimembo forest is surrounded by Lac Soamalipo to the west, and Lac Ankerika to the east. The collection localities of N. griveaudi are detailed for the two individuals collected in the National Park of Tsimanampetsotsa. The specimen from the northern part is from the open Mitoho cave. The individual from the southern portion is from the Mahafaly plateau, just above the lake, at an elevation of ca. 80 m a.s.l. The latter is covered with spiny forest reaching 5 to 8 m in height [6], and lies at an elevation slightly below the mean elevation of the plateau, therefore sustaining a microclimate with more humidity as compared to the surrounding area.

N. andrafiabe sp. n. is only known from its type locality in the Special Reserve of Ankarana (Fig. 2), in the vicinity of Andrafiabe cave. The type of vegetation has been defined as western dry forest [15], while some authors attribute a subhumid type of forest with evergreen trees in some valleys (Fig. 5).

(Colour online.) Dry forest in Ankarana reserve during the rain season with the typical karst topography and a river disappearing in a sinkhole to continue underground.

Picture by Sarah Langrand.

Sister species always inhabit environment that bear some similarities, which is exemplified in niche conservatism, e.g., [16,17]. In light of the current distribution of the genus Neogrosphus, with species able to cope with the extreme subarid conditions of Cap Sainte Marie (Fig. 2) where the vegetation is of a low thicket, to the subhumid Ankarana with tall evergreen trees, suggesting that the ancestor clade of the current species lived in both types of habitat. This is also exemplified by the current distribution of N. griveaudi in some southern refugia of its range, as in the case of Tsimanampetsotsa (Fig. 2).

The patchy distribution of the genus Neogrosphus, and the micro-endemic new species is best explained by allopatric speciation. Allopatry is usually caused by geographic barriers. The scorpions have extremely limited dispersal abilities. They spend most of their lives hidden under rocks, bark of trees, termite mounds or a hole dug in the earth [18]. Further traits indicating limited dispersal abilities are the comparatively slow embryonic and post-embryonic developments, which are unusually long for scorpions [19]. However, ‘long’ distance dispersal cannot be excluded as in the case of a floating tree. As a global rule, it is suggested that most scorpions either cope with their environment or die [20]. If species diversity in any given area is caused by speciation, extinction and dispersal [21], there are only two processes driving the scorpion diversity: speciation and extinction [20]. This rule certainly applies to most groups with limited dispersal abilities.

6 Proximate levels of current Neogrosphus distribution

The known species in the genus Neogrosphus may have an extremely old history going back to the Miocene. However, in order to explore and better understand the current distribution pattern of these species, and in light of our new data, we will limit our biogeographical considerations to the last million years circumscribed within the Plio-Quaternary.

In some recent papers, Lourenço [22–24] outlined that the global patterns of distribution observed for a given zoological group have largely been driven by historical factors. During recent geological times, e.g., the Pliocene (5.3–2.6 Ma), climate became cooler and drier, and also seasonal, with high frequency and low amplitude paleoclimate oscillations. During the mid-Pliocene, sea level has been 20–30 m above and below a value similar to current sea level, the equivalent sea level or esl [25]. The Quaternary, with the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs, has been characterized by low frequency and high amplitude paleoclimate oscillations, with alternating warm and cold periods at higher latitudes, and wet and dry periods at lower latitudes. During the dry periods of the Quaternary, the esl dropped to a minimum of −134 m during the recent Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) at ca. 21 ka BP [26]. During these dry periods, forests receded, together with forest-dwelling fauna and flora, except in some refugia [27,28] where the hydrological balance remained positive, and where forests have persisted [27,28]. The historical reduction of forests resulted in patch forests that served as refugia to surviving subpopulations. This is reflected by the existing biogeographical patterns of distribution and differentiation of several taxa in Madagascar [13,29], and is further supported by palynological and geomorphological evidence from many regions of the world [30].

Madagascar experienced a major tectonic phase during the Pliocene, and an increase in volcanic activity in several parts of Madagascar, which continued into the Quaternary. Some 100 earthquakes with magnitude 3 and higher are recorded every year in Madagascar, with highest density recorded in Central Madagascar, especially on the highlands, but not in the northern part of the island [31] (Fig. 6). The erosion gullies or ‘lavaka’ usually described as poster models for anthropogenic erosion [32] are especially correlated with active faulting and seismicity [33], with recent estimated erosion rates in river sediment average approximately 12 m/Ma [34]. It has been shown elsewhere that high erosion, together with efficient sediment transport such as cyclones, could also trigger shallow earthquakes [35].

(Colour online.) Simplified lithology and continental plateau, i.e., emerged land at Last Glacial Maximum with unknown sedimentary and vegetation cover. Collection localities of the species of Neogrosphus as on Fig. 2.

The littoral topography of western Madagascar is known to experience accretion, partly due to the high levels of erosion bringing larger quantities of sediments. The process is partly explained by heavy erosion with rivers carrying significant amounts of sediments into the ocean over the gently sloped foreshore and continental plateau (Fig. 6). The Sambirano coastland is no exception and shows heavy shore accretion, especially near the estuary of the Sambirano River [32].

Altitude and rivers have been proposed in several Madagascar studies as ecological barriers to fauna and flora. Both altitudes and rivers are dimensions of topography, which has an evolution dictated by the interactions between tectonics, climate and surface processes, i.e., erosion and sedimentation. To understand micro-endemism, consideration of topographic evolution needs to be taken into account to identify the historical ecological barriers to fauna and flora.

The island is currently experiencing active tectonic events over most of the central region, combined with heavy erosion throughout Madagascar, and volcanic activities in several places. These processes are continuously shaping the topography; they may be responsible for ‘rapid’ changes at a geological time scale. They can reorganize river systems, increase erosion, cover areas with lavas, or mud slides, over more or less extended areas. The induced changes have the potential to eradicate populations of scorpions and thus to separate a clade into different isolated populations. Amongst the possible processes able to create geographical or climatic barriers and thus separate populations in Madagascar, i.e., areas where subpopulations from the ancestral clade would have gone locally extinct are:

- • continental drift, topography and climate: with the elevation of the Tibetan plateau (Neogene), and subsequent strengthening of the Asian monsoon, together with the Afro-Malagasy plate drifting towards the north, the intense monsoonic system reached northern Madagascar during the Pliocene, with increased rain in the Sambirano region due to the local topography [36];

- • sea level rise, as during the mid-Pliocene;

- • tectonic activity with mud slides or river captures, as in the instance of the river which once flowed in the paleo-valley Itambono and has been captured by the Onilahy River, with consequent increased aridity to the north of Tsimanampetsotsa [37];

- • volcanism, as in the case of Quaternary volcanism on the highlands, and possibly along the Manasamody [38,39], Nosy Be and Montagne d’Ambre [39] (Fig. 6).

These processes would influence the distribution of several taxa, at different scales depending on their dispersal abilities, and tolerance to habitat change. In the case of a widespread Neogrosphus clade able to cope with subarid to subhumid environments, these processes could explain the isolated populations of N. blanci on the tectonic active highlands, the micro-endemic N. andrafiabe sp. n. from the extreme north, a possible micro-endemic in the Melaky center of endemism, and the absence of the clade in the humid Sambirano and areas with active volcanism.

7 Conclusion

The current habitat of the Neogrosphus species cannot explain their distribution, which is one of the obvious attribute of a species [40]. When considering the scorpions’ limited dispersal abilities in a ‘rapidly’ changing environment at the time scale of scorpion evolution, the processes invoked here as a possible explanation of the current vicariance observed in the genus Neogrosphus could also be the base to understand many of the wide ranged genera in Madagascar, typically genera nowadays occurring from subarid to perhumid bioclimates with distinct species in different regions. This would apply to the Diplopoda such as the micro-endemic Zoosphaerium tsingy [41] and Spiromimus triaureus [42], but also to Mammalia (e.g., taxa of Propithecus, Eulemur, Microcebus, or Cheirogaleus, amongst others). As a global rule, which would apply at least over the Pliocene and the Quaternary: the lower the species’ dispersal ability, and the greater the niche breadth of the ancestor taxum, the higher the species richness in a changing environment causing geographical barriers. The contrapositive applies to the Aves: in a changing environment, the lower the species richness, the higher the species’ dispersal ability, and/or the smaller the niche breadth of the ancestor taxum.

The processes implied here may not only explain the many cases of scorpion vicariance, but also the richness of several other clades, including in the Flora, the Diplopoda, but also Amphibia, Reptilia, and Mammalia. It can also be invoked to explain the paucity of the endemic avifauna in Madagascar.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to Bernard Duhem and Élise-Anne Leguin (MNHN, Paris) for their contribution to the preparation of the drawings and plates.