1. Introduction

Organoid and embryoid research stands at the forefront of biomedical innovation, offering unprecedented insights into human development and disease. This rapidly expanding field holds promise for both fundamental biological discoveries and translational medical applications. Like a previous Symposium in 2019, co-organized by the Académie de Médecine and the Académie des Sciences, on the same topic, the conference “Mini-organs and early embryos in vitro: what is at stake?” from the French Académie des Sciences, held on November 12, 2024 in the historical Palais de l’Institut de France in Paris, aimed to highlight the latest advances in organoid and embryoid research. Organized by Laure Bally-Cuif and Pascale Cossart, members of the Académie des Sciences, the conference explored organoids and embryoids potential, limitations, biomedical applications, and inherent ethical considerations.

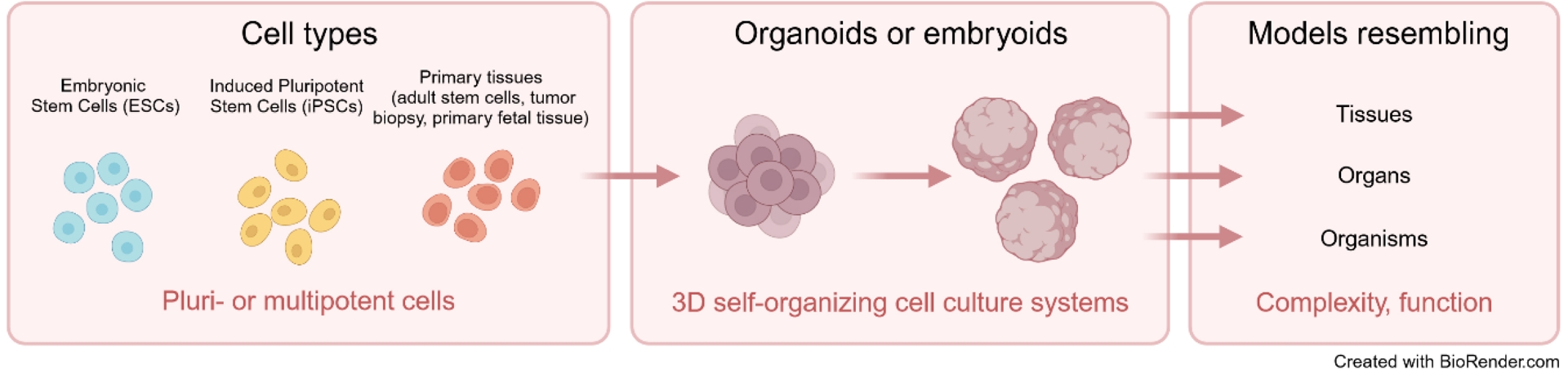

Organoids and embryoids are three-dimensional (3D) structures derived from pluripotent stem cells, such as embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), as well as from adult stem cells (ASCs), that self-organize and partially mimic the cellular complexity, function, and architecture of a tissue, organ, or organism (Figure 1). Differentiated skin or blood cells from human patients can be experimentally reverted to a pluripotent state and then guided in vitro to generate cells from various organs. Consequently, organoids have been extensively developed as models for studying human biology and diseases, encompassing nearly every organ from the intestine to the brain. Embryoids, a more recent experimental approach, help study early developmental and implantation stages that are inaccessible in vivo.

From stem cells to complex 3D models. Schema illustrating the progression from pluri- or multipotent cell types, such as embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and primary tissue-derived cells, to self-organizing 3D culture systems known as organoids or embryoids. These structures mimic biological tissues, organs, or even whole organisms in terms of complexity and function, providing advanced models for biomedical research. Created in https://BioRender.com.

The primary goals of generating organoids and embryoids are to advance our understanding of fundamental biology by exploring cellular properties, abnormalities, and diseases. Within this frame, Nathalie Vergnolle, director of the Digestive Health Research Institute in Toulouse, France, illustrated how intestinal organoids serve as powerful models for studying intestinal biology, such as epithelial regeneration, chronic inflammatory diseases, and drug responses, emphasizing their potential in precision medicine. Similarly, Botond Roska, founding Director of the Institute for Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology at the University of Basel, Switzerland, highlighted the use of retinal organoids in developing gene therapies for eye disorders, and screening protective compounds for photoreceptors. In the context of neurodevelopmental research, Sandrine Passemard, Professor in Child Neurology at Université Paris Cité and Hôpital Robert Debré in Paris, France, demonstrated how brain organoids help model disorders such as Coffin-Siris and Timothy syndromes, revealing key genetic and cellular mechanisms underlying these conditions.

Beyond their biomedical applications, organoids and embryoids also provide a unique opportunity to explore the genetic basis of developmental disorders and early embryogenesis. Denis Duboule, Professor at EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland, and Collège de France, Paris, France, discussed how embryo models, such as embryoids, gastruloids, and blastoids, contribute to understanding mammalian development, fertility, and congenital disorders. As these models advance in replicating human development and function, the conference ended by examining the necessity of addressing their ethical and societal implications. Hervé Chneiweiss, currently Chair of the Inserm ethics committee, showcased the HYBRIDA project to emphasize the importance of harmonizing ethical guidelines, defining clear regulatory boundaries, and ensuring responsible research practices in organoid studies.

2. Intestinal organoids: past, present and future in research and medicine

Nathalie Vergnolle’s presentation focused on the intestine, emphasizing the regenerative capacity of the intestinal epithelium, which is rich in stem cells. A key structure, the intestinal crypt, where intestinal stem cells reside, continuously undergoes proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, leading to the rapid renewal of the epithelium in less than a week. Since Hans Clevers’ pioneering experiment demonstrating the successful in vitro reproduction of an intestinal epithelium (Sato et al., 2009), further studies have shown that human colon crypts can form colonospheres, which subsequently generate colonoids within 10 to 12 days (d’Aldebert et al., 2020).

Intestinal organoids, derived from non-transformed tissues (including small biopsies), provide valuable models for studying developmental biology, cellular organization, and fundamental processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and cell death. Importantly, they reproduce key epithelial functions, including secretory, absorptive, and barrier functions, making them highly relevant for research in both physiology and pathophysiology. One major pharmacological application involves the study of protease-activated receptors (PARs), whose pro-inflammatory and pro-nociceptive effects have been identified (Vergnolle, Bunnett, et al., 2001; Vergnolle, Hollenberg, et al., 1999). The impact of thrombin on the intestinal epithelium has also been investigated, leading to the testing of PAR-1 and PAR-4 antagonists to assess their effects on epithelial maturation (Sébert et al., 2018).

In the field of pathophysiology, organoids serve as models for chronic inflammatory diseases after treatment with inflammatory cytokines or deriving organoids directly from patient cells (d’Aldebert et al., 2020). Notably, organoid cultures from Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis patient tissues maintain an inflammatory phenotype. Observed phenotypic changes in inflammatory disease models include alterations in organoid size, increased cell death and debris, and disruptions in polarity and barrier function. Given the role of the intestinal epithelium in protease secretion, researchers tested a serine protease inhibitor on diseased organoids, successfully restoring organoid size, polarity, junctional integrity, and budding formation. This finding highlights the therapeutic potential of organoid-based studies. Furthermore, organoid models play a crucial role in drug screening for therapeutic development, with the ultimate goal of restoring a healthy epithelial phenotype.

In the context of precision medicine, intestinal organoids offer a means to overcome patient-specific drug resistance. By testing treatments such as anti-TNF, methylprednisolone, and 5-ASA on organoids, researchers can evaluate drug efficacy based on parameters like size and polarity. One of the most promising applications is in colorectal cancer, where a strong correlation has been observed between organoid responses and patient outcomes. In the future, addressing the time constraint in obtaining results, which currently takes around six weeks, will be crucial.

Despite their advantages, several challenges remain in intestinal organoid research. These include improving co-cultures with gut microbiota, enhancing system complexity through vascularization, and developing novel techniques such as organ-on-a-chip models. Future applications for intestinal organoid cultures extend beyond research, with promising prospects in in vitro clinical trials, precision medicine approaches, and tissue engraftment for epithelial regeneration. These advancements are expected to drive rapid progress in regenerative and precision medicine, further expanding the potential applications of intestinal organoids.

3. Developing new therapies using human organoids

Botond Roska discussed the visual system, highlighting the complex pathway through which visual information is processed, from images to the retina, then in the brain to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), and finally to the cortex. Before transmitting information to higher visual centers, the retina processes approximately 30 different visual features, underscoring its critical role in visual perception. However, studying retinal diseases presents significant challenges due to the retina’s intricate organization, which consists of more than ten different cell types. Many retinal diseases are cell-type specific, making animal models inadequate for accurately replicating human retinal pathologies. A promising alternative is the development of human retinal organoids derived from iPSCs (Cowan et al., 2020), which facilitate high-throughput research and therapeutic applications.

These organoids have become instrumental in therapy development, particularly in gene therapy for vision restoration as exemplified by DNA base editing for Stargardt disease, and drug discovery for photoreceptor protection. As a prerequisite for human gene therapy, Botond Roska’s team developed AAV-based gene therapy vectors to allow efficient and long-lasting transgene expression in targeted retinal cells. This approach improves the efficacy of gene therapies aimed at restoring visual function (Jüttner et al., 2019). A particularly promising application is the development of DNA base editing therapies for Stargardt disease, a juvenile form of macular degeneration caused by a G-to-A mutation (c.5882G>A) in the ABCA4 gene, leading to foveal degeneration. This novel therapeutic approach has successfully corrected the mutation in approximately 70% of patient-derived retinal organoids (Muller et al., 2025), demonstrating significant potential for future clinical applications.

Retinal organoids also play a critical role in identifying compounds that protect photoreceptors from degeneration, a major cause of vision loss. Cone cells, in particular, are highly vulnerable under low-glucose conditions, necessitating therapies that slow down their deterioration. Researchers have developed a cone-specific labeling technique to track cone health, and AI-based analysis of cone-GFP-labeled organoids in 96-well plates enables large-scale screening, testing up to 15,000 organoids. Promising compounds identified in primary screenings undergo dose-response assays to assess their effectiveness in preserving cone function (Spirig et al., 2023).

Looking ahead, the field aims to develop a complete eye model that integrates all retinal components, providing an even more comprehensive system for studying vision and advancing therapeutic strategies. Retinal organoids thus represent a transformative tool in ophthalmic research, bridging the gap between basic science and clinical applications.

4. Modelling neurodevelopmental disorders in children using human brain organoids: current progress and challenges

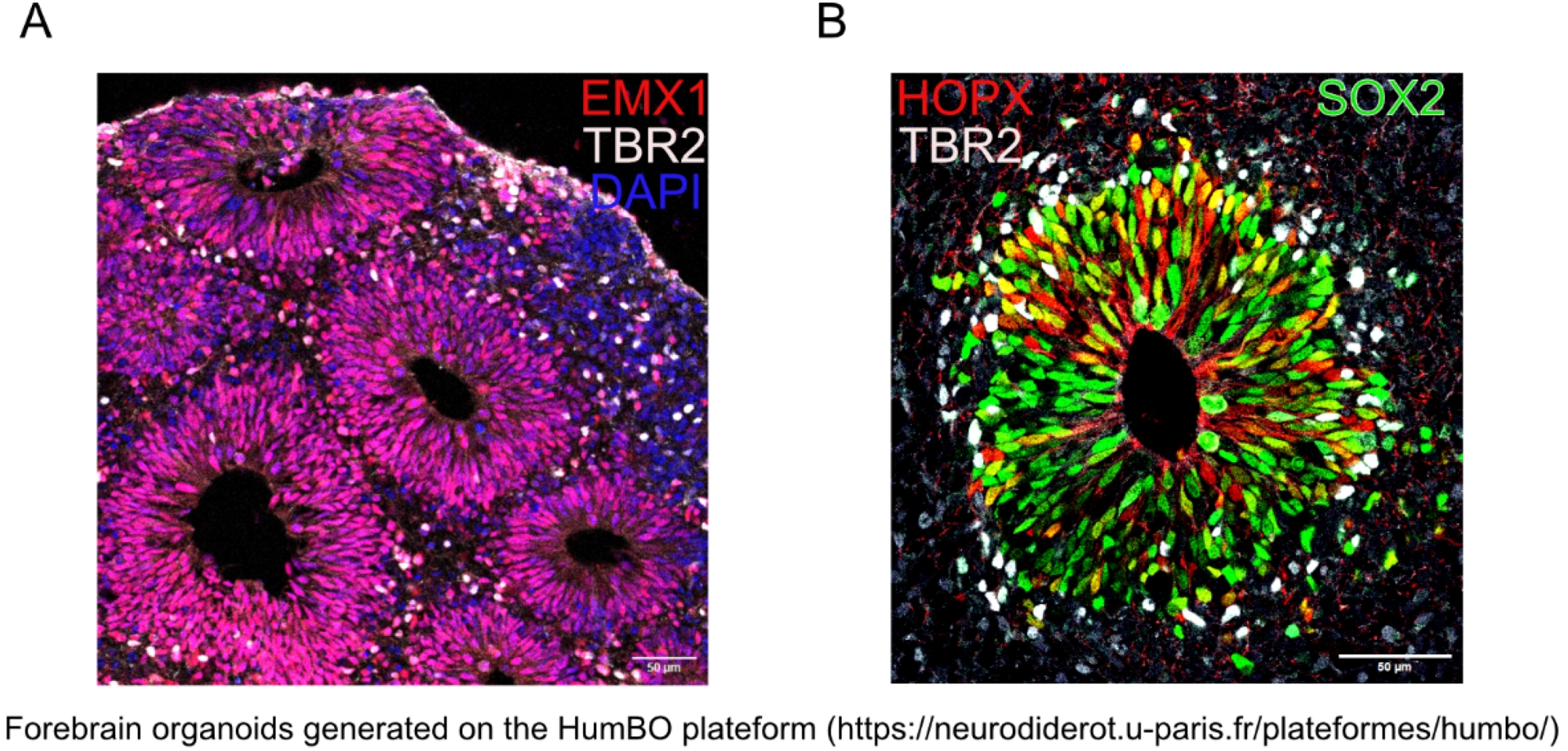

Since their recent development (Lancaster et al., 2013), organoids have provided crucial insights into brain development, especially on the fundamental interspecies differences in cortical progenitors. In humans, basal radial glial cells play a key role in cortical expansion, a feature that brain organoids have helped to model effectively. Both guided and non-guided organoids preserve differentiation processes similar to those of the fetal brain while retaining identical genetic information (Figure 2).

Brain organoids recapitulate the very early stages of human brain development in vitro, especially neurogenesis. (A) Guided cortical organoid at day in vitro 32, featuring apical radial glial cells expressing EMX1 (red), which are located and polarized similarly to the ventricular zone around the ventricular lumen. Intermediate progenitors expressing TBR2 (white) are present in the subventricular zone. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Guided cortical organoid at day in vitro 50, showing basal radial glial cells (HOPX+, red), apical radial glial cells (Sox2+, green) and intermediate progenitors (TBR2+, white). Scale bar: 50 μm (A, B). Figure kindly provided by S. Passemard.

One of the major challenges in studying neurological diseases is the difficulty of predicting early pathological events before the onset of symptoms in patients. Historically, researchers have relied on phenotypic characterization and animal models to understand disease mechanisms, but these approaches present limitations. Since the brain is one of the most evolutionarily divergent organs across species, developmental defects in the human brain cannot always be accurately replicated in animal models, even when major developmental processes are conserved. The generation of 3D brain organoids from patients’ own skin or blood cells has revolutionized the field by overcoming these limitations, providing an accessible and physiologically relevant platform for disease modeling.

Brain organoids have proven particularly valuable in studying neurodevelopmental disorders, which can have either genetic or acquired origins. Sandrine Passemard discussed several diseases modeled using these organoids. In the case of Coffin-Siris Syndrome, the most common cause is a monoallelic mutation in ARID1B, leading to agenesis of the corpus callosum. In 2024, researchers investigated the role of SATB2-expressing neurons and found that, contrary to initial assumptions, the number of these neurons remained constant. However, they observed a significant reduction in axon formation, which they attributed to defects in axon guidance genes (Martins-Costa et al., 2024). Timothy Syndrome is caused by a G406R gain-of-function mutation in CACNA1C, leading to prolonged calcium influx due to delayed inactivation of the Cav1.2 channel. Studies using cortical organoids show that excitatory neurons abnormally retain postnatal expression of exon 8a, resulting in prolonged depolarization. Additionally, more complex organoid models including ventral telencephalic structures reveal impaired migration of inhibitory interneurons, linked to increased calcium influx. These findings highlight how the mutation disrupts both excitatory and inhibitory neuronal development, affecting overall cortical function (Birey, Andersen, et al., 2017; Birey, Li, et al., 2022; Paşca et al., 2011). This discovery has led to a therapeutic approach using antisense oligonucleotides targeting exon 8a, as described in a 2024 study by Chen and Pasca (Chen et al., 2024).

Brain organoids have also been used to study microcephaly, a condition affecting 2.5% of births that can result from environmental factors (including Zika virus infection) or from chromosomal or genetic causes. Genetic microcephaly was among the earliest neurodevelopmental disorders modeled using brain organoids (Lancaster et al., 2013). A key cellular defect identified was the premature differentiation of neural progenitors, a mechanism now under investigation by Sandrine Passemard’s team.

Recent advances in brain organoid technology have led to the development of assembloid models that integrate different brain structures or cell types, enabling more sophisticated studies of neural interactions. These include cortex-microglia assembloids, cortex-choroid plexus assembloids, and cortex-blood vessel assembloids, among others. By bridging clinical care and fundamental research, these organoid models provide a powerful tool for dissecting the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental disorders. Moving forward, their continued refinement will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of brain development and disease mechanisms at a higher level of complexity.

5. The making of embryos

Denis Duboule discussed the significance of developing embryo models to study mammalian development, recognizing that while fundamental principles of embryogenesis are shared across species, mammalian embryos, and notably human embryos, exhibit unique characteristics that require further investigation. The recent emergence of embryoids, blastoids or gastruloids, has enabled researchers to explore early developmental stages that were previously inaccessible due to ethical and legal constraints. These models provide invaluable insights into mechanisms that cannot be analyzed in human embryos, from pre-implantation to early organogenesis, yet they raise important scientific and ethical questions regarding their biological status and potential applications. While these embryo models mimic certain developmental stages, they are not perfect copies of natural embryos but rather experimental approaches designed to explore specific aspects of early development.

The increasing relevance of embryo models is underscored by factors such as declining fertility rates and the rising average age of first-time parents, as well as the challenges of studying birth defects due to the inaccessibility of critical developmental periods. Embryo models can be classified as either integrated or non-integrated based on their potential to progress to the fetal stage. Integrated models aim to reproduce embryonic together with supporting extra-embryonic tissues, in a coordinated manner, whereas non-integrated models mimic only specific tissues, organs or anatomical structures of development.

Several types of embryo models have been developed to address specific research questions. Blastoids are structures that mimic blastocyst development. Mouse blastoids, first developed by Rivron et al. (2018), cannot implant in the uterus, whereas human blastoids, adapted by Rivron and Kagawa, utilize a permissive system that inhibits all non-epiblast signals (Kagawa et al., 2022). These human blastoids can implant in uterine mucosa organoids, providing a model for early human implantation while raising the question of whether such models could ever progress beyond this stage.

Whole-embryo models offer another avenue for investigating embryogenesis by integrating essential cell types. Mouse whole-embryo models require three cell types (epiblast, trophoblast and extra-embryonic mesoderm cells) (Sozen et al., 2018; Tarazi et al., 2022), whereas their human counterparts are more complex, involving a fourth cell type essential for the formation of extra-embryonic structures (hypoblast cells), as described by Hanna’s team in 2023 (Oldak et al., 2023). With mouse embryos having been successfully cultured for up to eight days (Aguilera-Castrejon et al., 2021), this advancement raises the question of whether extending human development in vitro is also feasible.

Non-integrated models, such as gastruloids derived from ESCs or iPSCs, provide another powerful approach to study early development. Although gastruloids lack full embryo organization, they allow researchers to investigate specific developmental processes such as the organization of the posterior embryonic body plan relative to the anteroposterior, dorsoventral and mediolateral axes. Martinez Arias’ research in 2017 showed that gastruloids primarily develop posterior identity, as indicated by Mesp1 expression (Turner et al., 2017). These models serve as experimental paradigms, enabling the manipulation of key signaling pathways such as Bone Morphogenetic Protein using activators and inhibitors to explore their role in human development.

Ultimately, the choice of an embryo model depends on the specific research question raised. Some models are more suited for studying implantation, while others offer insights into later events of cell differentiation and patterning. However, the rapid expansion of embryo modeling research places the scientific community in an unusual and delicate position, as these models challenge conventional definitions of embryonic identity and raise concerns about their potential future applications. As research continues, it will be crucial to balance scientific progress with ethical considerations, ensuring that embryo models are used responsibly to enhance our understanding of fertility, birth defects, and early human development.

6. Organoids: from ethical issues to operational guidelines, the outputs of the HYBRIDA project

As a developing technology, organoids encounter both regulatory gaps and excessive regulation, highlighting the need for harmonized guidelines across EU Member States. Additionally, as these models become more complex and increasingly resemble human tissues, they also raise significant ethical concerns. In this context, Hervé Chneiweiss provided an overview of the EU-funded HYBRIDA project (2020–2024; www.hybrida-project.eu), which aims to establish operational guidelines for organoid research, promote research integrity through a responsible code of conduct, and explore the implications of the living nature of organoids. While organoids are not fully developed organs, they serve as valuable tools for research and therapeutic applications. Despite significant advancements in this field, animal models remain necessary due to the current limitations of organoid systems.

Within the HYBRIDA project, a Code of Responsible Conduct for Researchers on Organoids and Related Fields was developed and built upon the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (ECoC) to ensure reliable and ethical research using organoids. This Code provides guidance and promotes trust among scientists, evaluators, ethics committees, and the broader public while emphasizing respect for both researchers and donors. The approach follows the “Ethics by Design” framework while also integrating the more recent concepts of Reflexivity, Anticipation, and Deliberation (RAD). Additionally, HYBRIDA Operational Guidelines (OGL) describes the procedures on good research practices for organoids. These include MIAOU, which defines the minimal information required for organoid research; ECHOES, a checklist for ethical project evaluation; RICOCheck, a tool for ethics committees to assess compliance; and TRUSTED, a list highlighting the critical elements of the donation process. Donors’ informed consent remains a critical component, requiring prior approval with consideration of future applications. However, ethical questions persist regarding the withdrawal of consent in long-term research.

One of the key ethical challenges stands around the definition of organoids. While they model aspects of human organs, they are not complete organs themselves, leading to ongoing debate (Wu and Fu, 2024). Some organoid structures and integrated embryonic models, possess developmental potential, raising concerns about their classification. Ethical discussions also address the possibility of embryonic models reaching a “tipping point” where they become indistinguishable from human embryos, making it essential to establish clear regulatory boundaries. Strict prohibitions remain in place against testing any kind of implantation of an embryonic model in humans.

Research on neural organoids presents additional ethical complexities. Studies such as those led by Pasca’s team have raised concerns about the potential for consciousness and self-awareness in brain organoids (Miura et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2025). As these models become more advanced, a holistic and anticipatory ethical approach is required to navigate the uncertainties surrounding their use in research and medicine.

7. Conclusions

The conference “Mini-organs and early embryos in vitro: what is at stake?” provided a comprehensive overview of some of the latest advancements in organoid and embryoid research, highlighting their potential in biomedical applications such as disease modeling, drug discovery, regenerative medicine, and personalized therapies. The discussions underscored both the scientific promise and the ethical challenges associated with these rapidly evolving technologies. From intestinal and retinal organoids to brain organoids and embryo models, recent studies illustrate how these models are transforming our understanding of human development and pathology.

However, as organoid complexity increases, it becomes imperative to establish ethical guidelines and regulatory frameworks to ensure responsible research practices. The insights from the HYBRIDA project, as well as broader ethical reflections, emphasized the need for a balance between innovation and ethical responsibility. Moving forward, interdisciplinary collaboration among scientists, ethicists, and policymakers will be essential to harness the full potential of organoids and embryoids while maintaining ethical integrity.

This conference reaffirmed the importance of continued dialogue between the many players involved, and of research, to navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by these groundbreaking technologies. As the field advances, sustained efforts in refining organoid models, integrating novel methodologies, and addressing ethical concerns will be crucial to unlocking new therapeutic possibilities and deepening our understanding of human biology.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the French Académie des Sciences for funding this conference, to Anastasia Gestkoff-Bodin for on-site organization, and to Antoine Triller, Secrétaire Perpétuel, and Alain Fischer, Président of the Académie des Sciences, for their support. MT was funded by postdoctoral fellowships from the Roux-Cantarini program and LabEx Revive (ANR-10-LABX-0073).

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0