The present episode of mass extinction of living species stands, in these first years of the XXIth century, as a major component of the global environmental crisis. Therefore, the preservation of biodiversity must be considered as a prerequisite amongst a number of other involvements required to achieve a sustainable development, which is the ultimate goal for mankind. Among others endpoints, the answer to such a challenge implies an urgent need in research especially in ecology.

Contrary to a commonly accepted view, the very term of biodiversity has not been defined at the time of the Rio Convention (1992). According to Wilson and Peter [1], it has been coined during the eighties and W.G. Rosen first quoted it in 1985, in the framework of the Life Sciences Commission of the American NAS. However, it was previously in use into the IUCN Commission on Ecology thought the IUCN “World Conservation Strategy”, officially released in March 1980, still relied on the term of genetic diversity instead of biodiversity.

Yet, the very term of Biological Conservation was given much prominence as early as 1978, when was held the first international Congress on Conservation Biology. However, it was already currently in use since several years... For example, the journal “Biological Conservation” founded by the late E. Duffey was first issued in 1976.

As a consequence of the contemporary mass extinction episode strictly related to man's impingement on the biosphere, the biodiversity conservation and management, which is the aim of this to day congress, stands as one of the most burning issue of the contemporary global environmental crisis, and ranks therefore amongst the most important need in research to which the contemporary ecology has to cope...

Therefore, the response to the scientific problems related to Biodiversity has to be considered as one of the major commitments for scientists involved in the biological field. First of all, the biodiversity has to be fully assessed. The present number of species described by science is over 1.7 millions [2]. More accurate counts is likely to produce higher figures in spite of a still current debate on the importance of the synonymy weighting in the accuracy of such assessment... This number of described species has to be confronted to the assessment of the ones of actually existing species in the biosphere which would be at the least 8.5 millions according to May [3], but which might reach as well 13.6 Millions [4]...

Another major challenge to the biological conservation is to conceive and define conceptual approaches and strategies to achieve the biodiversity conservation in the long run. If we pay some attention to the current scientific literature issued during the last decennial, National Parks and others similar nature reserves have deserved a special attention as areas of outstanding interest for the research in Conservation Biology both for their importance for the assessment of a still vastly ignored biodiversity and for their relevance regarding research in ecology [5]. Quite obviously, protected areas are of an outstanding interest for the research in ecology both fundamental and applied to the preservation of the ecosystems and of their biodiversity – particularly to the biodiversity management – and more generally speaking to the rational use of the natural resources (i.e. [6]).

The protected areas: national parks and others equivalent nature reserves are basically selected for their unusual species richness and endemism not to mention the occurrence of a number of habitats into their boundaries which are of unusual interest for biological research, particularly in ecology. More broadly speaking, the overall term of reference for selecting protected areas is their importance for preserving outstanding ecosystems as well as various vital fundamental ecological processes occurring into the concerned areas.

However, the present protected areas, everywhere in the world, do not display equal importance and relevance for the ecological research according to their regulatory status. Indeed, the modern Protected Areas are divided into several categories, which have been devised by two International Organisations both related to the UN System.

The World Union for Nature, formerly International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural resources (IUCN), implementing a resolution taken by the 27th session of the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations held in 1959 has defined several categories of Protected areas and since 1975 publish yearly the UN list of Protected areas. The number, definition, ranking and international status of these protected areas has undergone several modification during the last 40 years.

The most recent revision of the protected areas achieved by the IUCN-WCMC in 1997 [21] has defined six major Categories of such areas, which are presently the term of reference for the World List, regularly compiled by the IUCN-WCMC for the United Nations: I – Strict Nature Reserves; namely, protected areas managed mainly for science; II – National Parks: protected areas managed mainly for ecosystems protection and recreation; III – Natural Monuments: protected areas managed mainly for conservation of specific natural features; IV – Habitat/species management Areas: protected areas managed mainly for conservation through management intervention; V – Protected Landscapes/Seascapes protected areas managed mainly for Landscapes/Seascapes conservation and recreation (i.e.: French Regional Natural Park – PNR); VI – Managed Resources Protected Areas: protected areas managed mainly for sustainable use of natural ecosystems.

Independently, the Unesco has devised and enacted during the seventies two additional categories of protected areas: the Biosphere Reserves and the World Heritage Sites. The Biosphere Reserves [7] are especially devised for the research especially in ecology and field biology. On the other hand, their major specificity lay in an elaborated zonation, which stands in a decreasing level of conservation from the centre to its boundaries. A more or less central core area is devised as a strict nature reserve fully devoted to research activities, surrounded by a buffer zone where may occur a given level of use of its natural resources and a peripheral zone, with human settlements where can occur agricultural and others activities managed in such a way that they do not jeopardize the stability of the concerned ecosystems and habitats. Lastly the World heritage sites though mainly conceived in order to protect outstanding historic and cultural sites – generally monument – and even cities as a whole which display major importance for the mankind civilizations may in held areas of special ecological interest.

1 Research in protected areas

During the second half of the XXth century, the biological research in protected areas has acknowledged an impressive growth in field biology and especially in ecology both fundamental and applied.

1.1 Fundamental ecology: research in protected areas

A number of news insight in fundamental ecology have been developed since several decennial, thanks to research carried out in protected areas (see for example the outstanding and pioneering works started in the fifties of Bourlière and Verschuren, [8] in the national parks of the former Belgian Congo, of Bourlière and Hadley, [9] in east African protected areas, and the ones of Odum and Pigeon [10] in the Puerto Rico tropical rain forest reserve. They are related both to studies on the ecosystems structure and ecosystems functioning. Regarding ecosystems structure one have to quote the importance of protected areas for the achievement of studies on undisturbed habitats and on the influence of ecological factors on populations occurring into them, as well as on the identification of keystone species, which stands as a major issue for the understanding of the mechanisms controlling the communities structuration as well as various fundamental ecological processes. Another fields of investigations where protected areas have proven of an outstanding importance is the appraisal of the biodiversity of plants and animal communities which is still a poorly assessed ecological dimension, and the ones of endemism, a key factor for determining the species vulnerability. More recently, protected areas have brought a significant contribution to the assessment of world biodiversity Hot Spots [11]. Last but not least, the protected areas are of a special interest regarding research on insularity, a major issue for the conservation of the biodiversity. Indeed, and taking apart true oceanic or continental islands which are example of natural insularity, a growing number of such areas are man made as they are more an more isolated, being converted to “islands” by man's activities for surrounded by vast areas deeply disturbed subsequently to the development of intensive agriculture, industrialisation, urbanisation, transportation network etc. [12]... On the other hand protected areas afford invaluable opportunities for studies on the ecosystems functioning and dynamics. In spite of a number of recent and significant progress in the study of fundamental ecological process, which is as well a major issue for securing the biodiversity conservation, there is still a basic need of improving the understanding of their mechanism both at qualitative and quantitative standpoint. As protected areas are generally selected and are located in places where man's made perturbations are at their lowest level and even negligible, they afford us unique opportunities for studying for example biogeochemical cycles and productivity patterns.

1.2 Research in applied ecology and its involvements in the preservation of biodiversity

Amongst a number of applications of the ecological research into protected areas to biodiversity preservation, we may quote the monitoring of biological diversity, the assessment of the level of conservation or of the ranking of the more urgent actions to be taken regarding a group of threatened species in urgent need of protection [13]. As well, predicting threats to biodiversity appears as one of the most burning issue for its conservation both into and outside protected areas [14]. Protected areas stand as outstanding place for the ecological and more broadly for the environmental Monitoring. More especially, they afford a major interest for the assessment of the categories of the threatened species as they in held frequently the places where the majority of the extant individuals of these species is still living, they also offer the best opportunities for the assessment of the population status and dynamics of the concerned taxa. They afford as well major opportunities for transferring the results gained by the research in theoretical and fundamental ecology to the conservation of threatened ecosystems and of their biodiversity. Last but not least, they prove invaluable as field for experimentations intended to the restoration of degraded ecosystems, a prerequisite to the reintroduction or the safeguarding of any species threatened by the loss of habitats one of the most frequent cause of extinction. It is presently quite obvious that the management of Protected Area and of their Biodiversity has to rely on a permanent transfer from the data brought by ecological research. Previous studies have allowed to define several levels of conservation (Fig. 1) according to the urgency ranking in order to meet the needs of preserving the biodiversity [13]: from the more stringent to the lowest level of conservation one may define: an ex situ conservation, namely the one's provided by zoological or botanical gardens [15], germoplasm banks, frozen embryos depository, etc. [16]... The in situ conservation stands as the most widely distributed way of preservation of the biodiversity. Namely, it is the conservation afforded by the national parks, nature reserve and others kind of protected areas. The major interest of this kind of preservation is that it gives a protection both to habitats and ecosystems taken as a whole and therefore of their biodiversity. Additionally as the populations of the preserved species breeds and thrive in the environmental conditions proper to their natural habitats, they are permanently under the influence of the ecological factors that have generated their speciation and the natural selection which has led to the genetic characteristics of their concerned wild populations. Therefore they cannot undergo a genetic drift, quite unavoidable in the same population that would be protected ex situ. Lastly, ones have to address the preservation of biodiversity outside the protected areas, which cover the vast majority of the landmass and where stay the highest number of habitats and species. Another challenge to the management of the biodiversity is to secure its preservation outside protected area. Obviously, the bulk of the world biodiversity is located outside protected areas. It is quite clear that even if 10% of the emerged lands were kept in strict nature reserve which would be a brave new world of the conservation, according to the present state of affair of the biodiversity decline at the global level – about 50% of the existing species on the 90% remaining area would be driven to extinction in the long run due to the impingement of man's activity and development on the transformed or even merely destroyed ecosystems... Therefore, it is obvious that the goal to secure the preservation of the world biodiversity would require new management strategies in order to safeguard a highest number of species living outside protected areas. This would first imply new way of land use and agricultural practices. On the other hand this goal would require the enactment of new kind of protected habitats like the Natura 2000 sites in the EU – and on the other hand to manage corridor between the various nature reserve in order to obviate to the growing habitats fragmentation outside the existing protected areas, process which is very frequently implied in the loss of biodiversity (see i.e. [17–19]). Lastly, this would require a careful selection of areas devoted to urbanization and industrialization. Namely, these areas would have to be located in places where the biodiversity is at its lowest.

The iceberg of conservation. This picture symbolizes the various levels of the biodiversity preservation. The emerging part of the iceberg figures the ex situ conservation of living species namely in botanical gardens or Zoo. The submersed part is the in situ conservation, which can be divided in two parts. The upper one is related to the species conservation in protected areas (national parks and others analogous nature reserves), the lowest part figures the remaining continental area which currently under more or less intensive use par man's activities and development largest area of the earth surface land and does not benefit as such of any conservation measure (after [13]).

2 The research-management dynamic

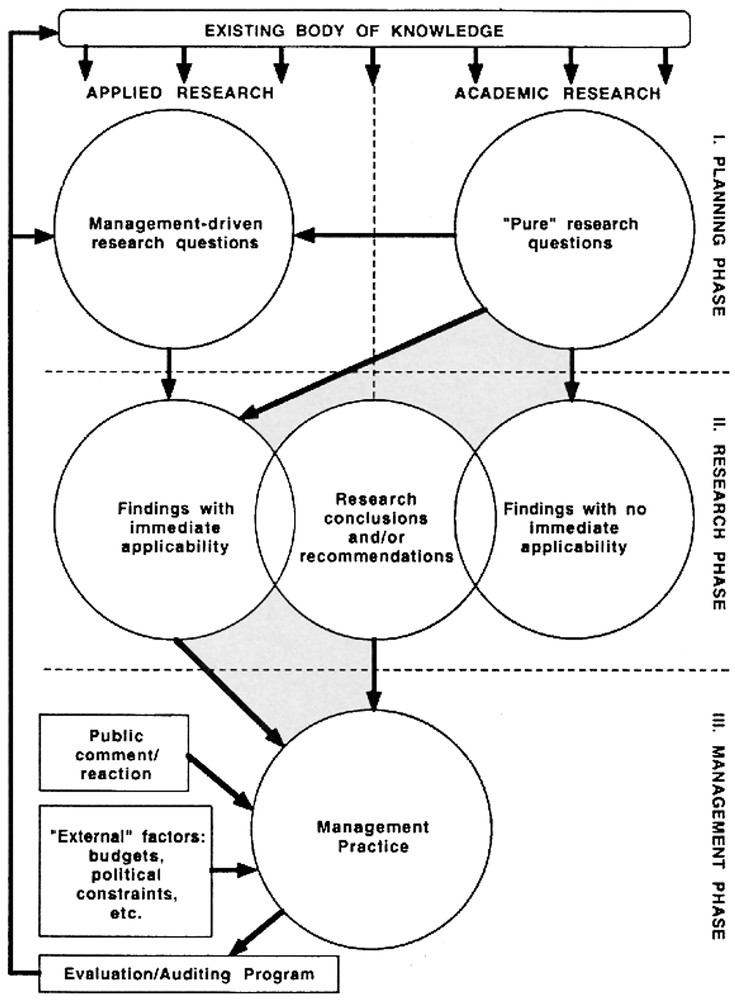

In practice, there is no absolute, stark division, between applied and fundamental research: as far as Ecology is concerned, the two grade frequently into each other. However the cleavage is useful for visualizing the research management dynamic (Fig. 2). Amongst a number of prerequisite related to the biodiversity conservation ones must emphasize the needs of a more intensive transfer of results – from academic research to the management of protected areas and others places where occurs a high level of biodiversity. Conversely, practical issues related to a number of problems arisen by the preservation and management of the biodiversity arise many fundamental questions unsolved and sometimes still poorly understood. Therefore, more and more protected areas agencies support the need for a sound scientific program for the management of the concerned ecosystem and their biodiversity [20]. Among various issues related to the management of the biodiversity we would quote for example the problem, still unsolved of adjusting quantitatively the balance between the need to decrease intentionally the populations of an alien predator in order to protect the birds endemic species which it jeopardizes, after its introduction on a given islands- and the subsequent rise of a population of an invasive introduced species which is controlled by the same predator. As a conclusion there is obviously an urgent need to increase the support to the research in conservation ecology more especially on what regards the global biodiversity assessment and monitoring. Last but not least, another major requirement is to insure a better implementation of the transfer from these fundamental research data to the conservation practices in order to improve the efficiency of the management plans of protected areas particularly in what regards their biodiversity conservation.

Overall scheme of the research-management dynamic in protected areas (after [5]).