Abbreviations used

Hb: Human adult hemoglobin; MWC: Monod, Wyman, and Changeux; DPG: 2,3-diphosphoglycetrate; IHP: inositol hexaphosphate; P50: partial pressure of O2 at half-saturation.

1 Introduction

The sigmoidal O2 binding behaviors of Hb, which are accompanied by remarkable changes in the color of Hb between dark red and bright red, have fascinated many, since they represent one of the simplest models of biological regulation and control. Hemoglobin, a heterotetramer, consists of two α- and two β-subunits, each of which contains one O2-binding heme group. These subunits are paired as two dimers, α1β1 and α2β2. Thus, it was considered that the sigmoidal behaviors resulted from each of the four successive O2-binding processes of Hb altering the O2-binding affinities of the remaining heme groups either directly via an electronic heme–heme interaction or indirectly through some oxygenation-linked changes of the protein conformation. The Adair Equation (Eq. (1)) [1], which includes five variables, i.e., four independent O2-binding equilibrium constants (K1,K2,K3, and K4) and the partial pressure of O2 (p), can represent the O2-saturation function of Hb (Y) well in a model-independent fashion. Thus a set of these four Adair equilibrium constants have been used to quantitatively characterize the sigmoidal behavior of Hb, where a ratio of K4/K1 would be a measure of the degree of cooperativity.

| (1) |

2 MWC two-state concerted model

Muirhead and Perutz [2] demonstrated X-ray structures of unligated (deoxy) and ligated states of Hb to exhibit distinctly different quaternary structures (the packing mode of the two α1β1 and α2β2 dimers) without appreciable changes in subunit conformation (the tertiary structure). Then, the question of Hb mechanism became one of molecular mechanism. The inter-heme distances within Hb are too large to have the direct heme–heme interaction. The demonstration of two distinct quaternary structures of Hb by Perutz and coworkers had served as an impetus for Monod et al. [3] to propose the two-state concerted allosteric mechanism of regulatory proteins, including Hb. The MWC model proposes Hb to have two quaternary structures, the T state having low O2 affinity and the R state having high O2 affinity, which are in a ligation-linked allosteric equilibrium. The allosteric equilibrium favors the T (low affinity) state in the deoxy state, whereas the equilibrium shifts toward the R (high affinity) states upon oxygenation. The MWC Equation (Eq. (2)) [3] containing four variables, i.e., the O2 affinities (the equilibrium constants) of the T and R states (KT and KR), allosteric equilibrium constant (L0), and p has been shown to express the O2-binding function of Hb (Y) well and with remarkable consistency. Here a ratio of KR/KT represents an indicator of the degree of cooperativity.

| (2) |

The O2 affinities of T (deoxy) and R (oxy) Hb, KT and KR, were originally defined as dissociation equilibrium constants by Monod et al. [3]. However, they are defined as intrinsic association equilibrium constants in this article, in order to compare them with corresponding Adair equilibrium constants, K1 and K4, respectively. Therefore, Eq. (2) has been appropriately modified.

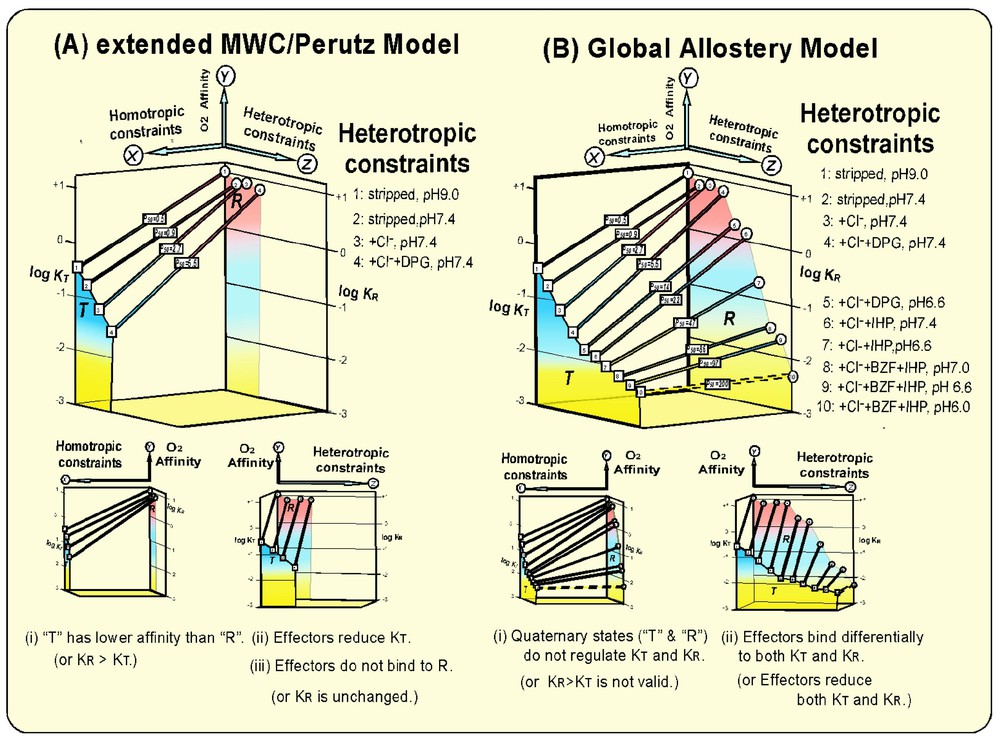

T (deoxy) Hb is structurally more constrained than R (oxy) Hb, so that its O2 affinity (KT) is reduced by a factor of ∼30 over that (KR) of the unconstrained R (oxy) Hb. The parameters of the O2-binding equilibrium of Hb quoted in this article were determined from the measurements in 0.1 M HEPES buffers with and without 0.1 M Cl− at 15 °C, where the concentrations of allosteric effectors employed were 2 mM DPG, 10 mM BZF, and 2 mM IHP [4,20]. The O2-affinity of Hb increases by a factor of ∼2 at a temperature difference of −10 °C. Therefore, the values of KT and KR as well as those of P50 and the Bohr effect (ΔP50/ΔpH) must be appropriately adjusted by this temperature factor in order to compare the present data with the corresponding data at different temperatures. Other parameters such as the allosteric equilibrium constant (L0 and L4) and the cooperativity (KR/KT) are not significantly affected by temperature. Consequently, a modest cooperativity (KR/KT ≈30) [4] is generated during the reversible oxygenation (Fig. 1A). This homotropic function of Hb in the O2 binding is linked to heterotropic influences on Hb caused by physiological allosteric effectors such as H+, CO2, and Cl−. These physiological effectors were considered to bind preferentially to T (deoxy) Hb. The interactions of these heterotropic effectors with T (deoxy) Hb shift the allosteric equilibrium toward the T-state [3] and consequently increase L0 values. However, KT and KR were considered unaffected by the heterotropic effectors.

Homotropic and heterotropic allosteric modulations of the O2 affinity (KT, KR, and P50) of Hb according to (A) the extended MWC/Perutz model [3,7,8] and (B) the Global Allostery model [4,20,21]. Heterotropic allosteric effectors do alter the tertiary structures of T (deoxy) and R (oxy) Hb without altering their respective quaternary states [4,20]. They lead to differential reductions of KT and KR, respectively and, consequently, modulations of the overall O2 affinity (P50) and the Bohr effect (ΔP50/ΔpH). The heterotropic, effector-linked tertiary structural constraints (the Z-axis) play energetically more dominant roles than the tertiary constraints induced by the homotropic, T/R quaternary transition (the X-axis) in the modulation of the O2 affinity (the Y-axis), and, consequently, the cooperativity and the Bohr effect from a global viewpoint of allostery in Hb.

3 Extended MWC/Perutz model

After Benesch and Benesch [5] discovered DPG to be a more potent natural effector of Hb, it was found that the binding of DPG to T (deoxy) Hb not only shifts the allosteric equilibrium toward the T state by further increasing L0, but also reduces KT as well [6]. Thus, the role of DPG, a natural potent allosteric effector, was expanded from a regulator of the allosteric equilibrium (L0) to a modulator of KT in the extended MWC/Perutz model (Fig. 1A) [7,8]. This, in consequence, results in the enhancement of the cooperativity up to KR/KT≈230 [4]. It is worthy to note that this maximal value of cooperativity is attained under the physiological conditions of the blood, i.e., at 0.1 M Cl− and 3–5 mM DPG at pH 7.4. Thus, the significant enhancement of its efficiency in unloading O2 to and in removing CO2 from tissues is achieved under physiological conditions. Some observations [9–13] reported that heterotropic effectors could bind to R (oxy) Hb. In fact, Kister et al. [12] first demonstrated that DPG does bind not only to T (deoxy) Hb but also to R (oxy) Hbs, resulting in downward modulations of both KT and KR, even at pH 7.4, if competing Cl− is removed. Binding of IHP to R (oxy) Hb to lower its O2 affinity (either K4 or KR) in physiological conditions has been well documented [11–13]. However, these heterotropic modulations of KR are relatively small in comparison with the homotropic modulation of the O2 affinity of Hb (KR/KT≈30). Furthermore, no crystallographic proof of the binding of a heterotropic effector to R (ligated) Hb was available. In fact, Perutz [7] showed that the interior cavity of Hb, where DPG binds in the T (deoxy) state, narrows upon the T → R transition, so that it cannot be accommodated in the same cavity in the R (ligated) state. Therefore, the binding of heterotropic effectors to R (ligated) Hb was not seriously integrated into the allosteric mechanisms of Hb, including the extended MWC/Perutz model [7,8]. Thus, the fundamental tenet of the extended MWC/Perutz model [3,7,8] is that the O2 affinity of Hb is primarily regulated by the structural constraints caused by the homotropic R→T quaternary structural transition. R (oxy) Hb exhibits high O2-affinity, since it is structurally unconstrained. On the other hand, the structural constraint imposed on T (deoxy) Hb reduces its O2-affinity (KT) in proportion to the degree of the constraint. Heterotropic effectors are considered to bind preferentially to T (deoxy) Hb, causing structural constraints in T (deoxy) Hb and lowering KT. This induces the enhancement in the cooperativity of Hb under physiological conditions. Under these conditions, L0 increases and KT decreases, whereas L4 and KR remain unchanged as the allosteric potency of the effector is increased [13]. It was assumed that in the presence of more potent effectors, L0 would increase significantly, resulting in allosteric equilibrium shift of R (oxy) Hb to ‘T’ (oxy) Hb (or R4 → T4). Therefore, the almost non-cooperative O2-binding behavior of Hb Kansas with an extremely low affinity (P50>100 torr) has been explained as its allosteric equilibrium being locked in the T (low affinity) state (L0⪢106) and thus being insensitive to the degree of oxygenation [14].

The essential question concerning the mechanism of regulation in Hb that needs to be addressed is to explain “how the low-affinity T (deoxy) state can store the free energy that is made available to bind ligands more strongly in the high affinity R (oxy) state”. Based upon the detailed structural data, Perutz [7] first proposed that inter-subunit salt bridges (formation/dissolution) were the keys to regulation. Difficulty in establishing the centrality of the salt bridges led Perutz to propose that the affinity was lowered by storing energy as strain at the heme moiety, perhaps because of the spin radius of the high-spin iron in the T (deoxy) state. However, spin energy and heme strains store insufficient energy to account for this cooperativity. Hopfield [15] then proposed a distributed strain model in which small strains throughout the protein stored the energy difference. Molecular modeling led Gelin et al. [16] to propose the movement of the proximal His pulling on the F-helix as a locus of strain energy storage. Related proposals based on resonance Raman data were also presented [17,18]. Nonetheless, no definitive experiment has successfully ascribed to any structural feature the amount of free energy required to account for the difference in the O2 affinity between T (deoxy) and R (oxy) structures of Hb.

4 Global Allostery model

Hb Kansas in solution [14] and T (deoxy) Hb in single crystals [19] have been reported to have extremely low affinities (P50>100 torr). Can the O2-affinity of Hb be reduced to these extremely low levels by stronger allosteric constraints? A recent comprehensive O2-binding measurement of Hb under a wide range of medium condition in the presence and absence of more potent allosteric effectors has brought about a new mechanism of allosteric regulation of Hb, the Global Allostery model (Fig. 1B) [4,20,21].

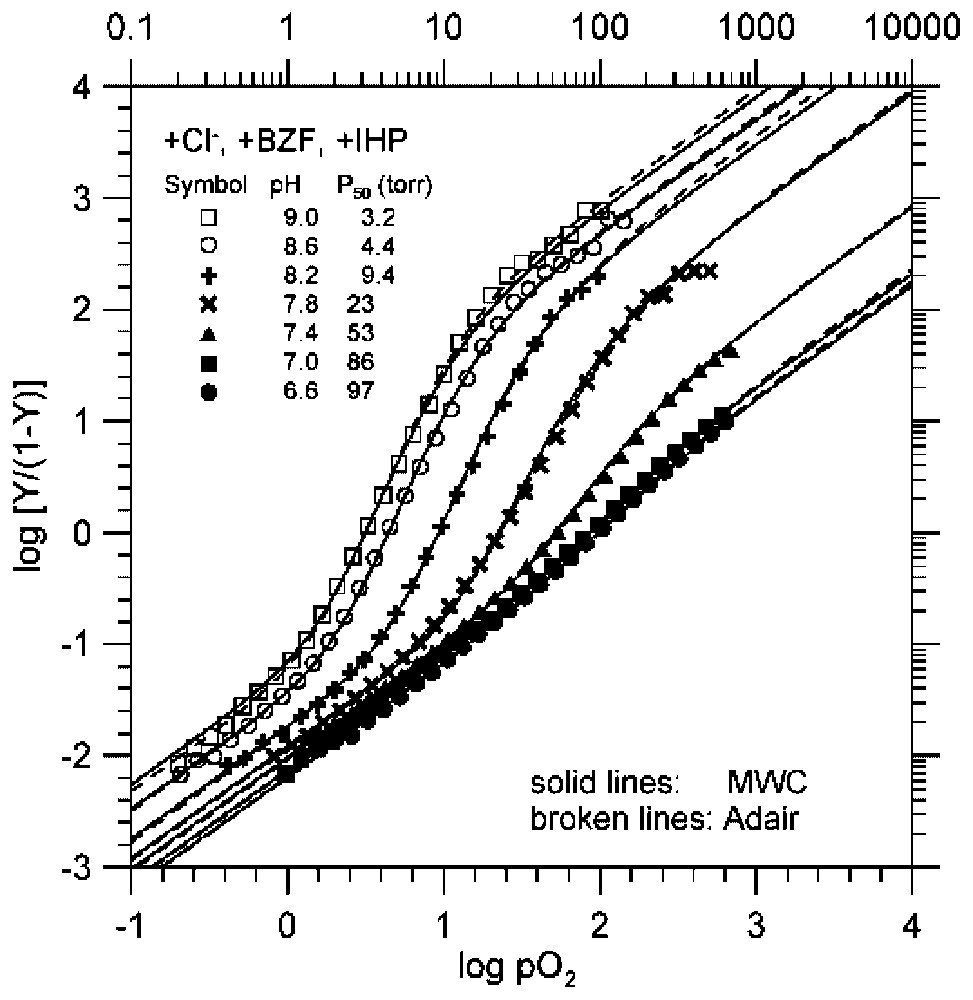

The MWC allosteric parameters were obtained by a non-linear least-squares regression curve-fitting analyses of O2-equilibrium. Processed oxygenation data were arranged in the form (logp, log[Y/(1−Y)]) and fitted with the custom-made non-linear curve fitting procedure in Origin Version 6.1 (Microcal, Nothampton, MA), according to Eq. (2). Initial estimates for KT, and KR could be readily obtained graphically from Hill plots, or fitted data sets according to Adair scheme. Namely, initial values of KT and KR can be estimated from the lower and upper asymptotes on the Hill plots. Alternatively, values of K1 and K4, which were determined from the Adair analysis (Eq. (1)) [1], were used as initial estimates for KT and KR, respectively. The L0 values were estimated with an approximation of L0≈(K4×P50)4 [20]. Unique sets of fitted values for KT, KR, and L0 were thus obtained after the convergence of successive iterations was achieved. Successive iterations using 10-fold increased or decreased initial values of KT, KR, and/or L0 were found not to alter the values of KT, KR, and L0 at the convergence. Simulations based upon these sets of KT, KR, and L0 were found to fit well with experimental data (Fig. 2). Furthermore, all the values of KT and KR so determined were numerically identical within experimental errors to corresponding values of K1 and K4, the O2-affinities of deoxy and oxy Hb, respectively, according to the Adair model [1]. Since K1 and K4 are model-independent parameters, the fact that numerical agreements of KT and KR with K1 and K4, respectively, would provide further credence to the values of KT and KR determined by the present MWC analysis. We have also attempted the non-linear least-square regression curve-fitting analysis of the experimental data according to the MWC model using initial estimates of low –0.05 torr−1), high KR (KR≈8–11 torr−1), and large L0 (L0≈108–1014) values. This was in consideration of the more traditional idea of the MWC model of variable low KT, fixed high KR, and large L0 values in the presence of potent allosteric effectors. The simulations, based upon the values of KT (ranging from 0.008 to 0.05 torr−1), KR (ranging from 9.2 to 12.8 torr−1) and L0 (up to ∼1013) obtained at the forced convergence, fit the experimental data reasonably well at low and middle saturation ranges of Hill plots. However, they consistently deviate from the data in high saturation ranges above 90%-saturation levels, and significantly overshoot the upper asymptotes of the experimental data. This is a clear indication that the estimated KR values are too large. Large L0 values of ∼1013, which are required to compensate the much larger difference between KT and KR values (KR/K≈2000) than those obtained under physiological conditions (KR/KT<230), appear too large to be realistically meaningful. Furthermore, the L4 values of ∼0.3 obtained at maximal constraints are not consistent with the structural data of R (oxy) Hb obtained from hydrogen-bonded proton NMR measurements [4]. Therefore, it is evident that (i) securing the precision O2-binding data at higher O2-saturation levels, (ii) choosing appropriate initial estimates of MWC parameters, and (iii) having corroborating structural evidence are critical in obtaining unique sets of ‘appropriate’ MWC parameters through the non-linear least-square regression curve-fitting analysis.

The pH dependence of O2-binding equilibrium curves of Hb in the presence of potent heterotropic effectors (a combination of Cl−, BZF, and IHP) [4]. The experimental data, shown one every other two data points for clarity, are consistent with simulations according to both the MWC two-state model (solid lines), in which all three MWC parameters, namely, KT, KR, and L0, were allowed to float [3], and the Adair model (broken lines) [1]. All the values of KT and KR [4,20] determined under the MWC two-state model [3] are numerically identical to the corresponding values of K1 and K4 [4,20] of the Adair model [1], i.e., the model-independent equilibrium constants of the first and fourth steps of oxygenation in Hb, respectively. These facts further increase the reliability and accuracy of the KT and KR values determined under the experimental conditions. Under these conditions, the effectors bind to oxy (R) Hb more strongly at decreasing pHs. This results in 500–1000-fold decreases in KR values. These highly pH-dependent behaviors of the O2-binding curves of Hb, i.e., the extreme pH-sensitivity of the overall O2-affinity (P50=3.1→97 torr), accompanied by a decreasing cooperativity (KR/KT=230→1.29), at decreasing pH from pH 9.0 to pH 6.6, are similar to those of the Root effect of fish Hbs [30].

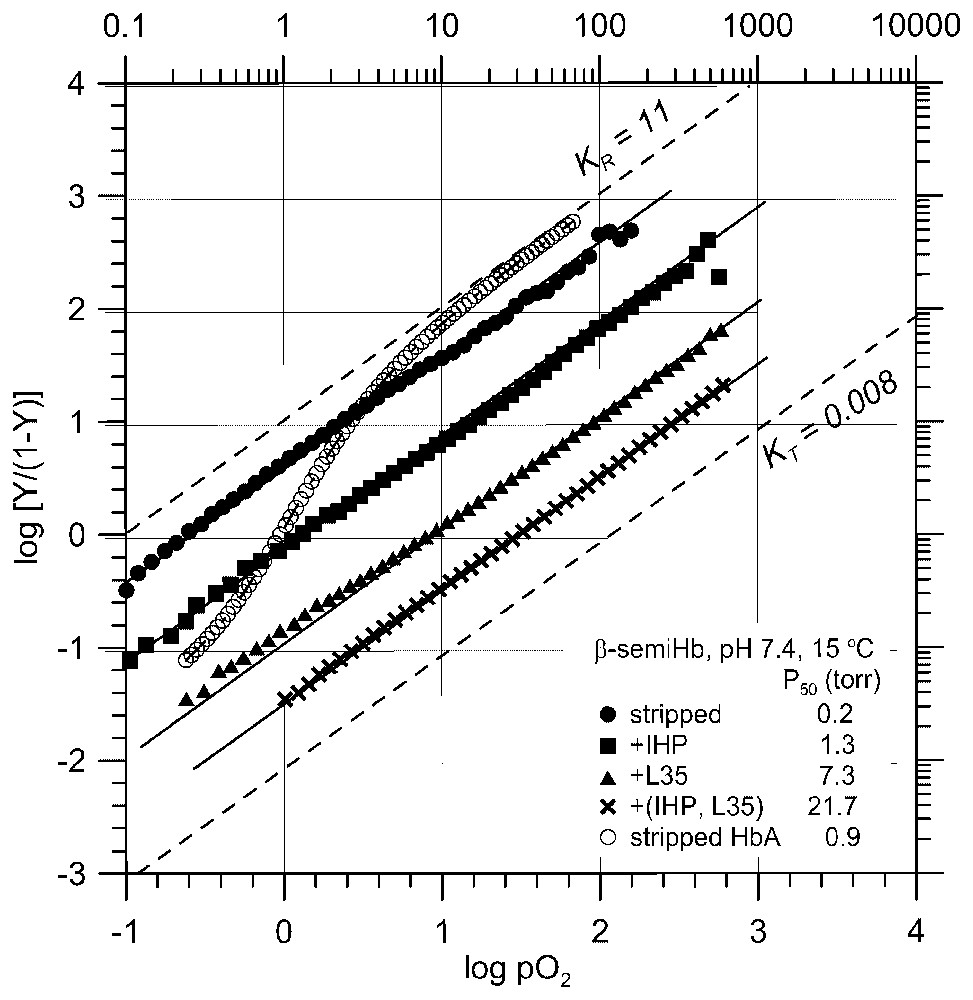

These studies have revealed that: (i) more potent allosteric effectors not only bind to T (deoxy) Hb more strongly, reducing KT down to ∼0.01 torr−1, but also differentially bind to R (oxy) Hb, reducing KR as much as >500-fold, down to KR≈0.05 torr−1, (ii) at the maximal allosteric constraint, KT and KR converge at KT≈KR≈0.005 torr−1 or P50=200 torr, (iii) with stronger allosteric effectors, L0 initially increases from 103 up to ∼107 with increasing allosteric potency. However, as soon as heterotropic effectors begin to bind to R (oxy) Hb, L0 starts to decrease at increasing allosteric potency down to as low as ∼10, (iv) at the maximal allosteric constraint, L0 is reduced to unity or [T0]=[R0] with no cooperativity. Various structural probes have shown that although they significantly decrease KT and KR values, heterotropic allosteric effectors do not alter the quaternary states of Hb in both T (deoxy) and R (oxy) states [4,20]. The L values of deoxy and oxy Hb in the absence of heterotropic constraints are lopsidedly in favor of T0 (L0=103) and R4 (L4=10−3), so that heterotropic effector-induced variations of L0 of several orders of magnitude would hardly affect the actual quaternary states of Hb in both T (deoxy) and R (oxy) states [4], contrary to the widely held assumption [7,8,14] that the quaternary state of Hb, especially that of R (oxy) Hb, is greatly influenced by heterotropic effectors. Therefore, one can reasonably conclude that the observed large amplitude modulations of KT and KR by heterotropic effectors (Fig. 1B) are caused by the tertiary structural constraints on T (deoxy) and R (oxy) states, respectively, by the interactions with heterotropic effectors. Consequently the cooperativity and the Bohr effect of Hb are regulated by the effector-induced tertiary structural changes, as illustrated in Figs. 1B and 2. Beta-semi-Hb, α(−)2β(Fe)2, is a non-cooperative, high-affinity O2-carrier. Its O2-affinity can be lowered as much as >100-fold (P50=0.2 torr →>20 torr) by potent heterotropic effectors (a combination of IHP and L35 [22]) even at pH 7.4, independent of homotropic T/R quaternary transition, since it is presumably an R-state Hb in both deoxy and oxy states (Fig. 3) [23]. Probably this is the most convincing evidence for the capability of heterotropic allosteric effectors to substantially reduce the O2-affinity of an R-state Hb through the effector-induced tertiary structural changes. These findings challenge directly the fundamental tenets of the MWC/Perutz model that the O2 affinity of Hb is regulated and controlled principally by the O2-linked T↔R quaternary structural changes. In essence, the Global Allostery model describes the functional diversity of Hb in terms of tertiary structural constraints imposed by the interactions with heterotropic effectors on both the T (deoxy) and R (oxy) states of Hb, which differentially lower both KT and KR, respectively. The quaternary-linked homotropic structural constraint on the T (deoxy) state of Hb, as depicted by the MWC/Perutz model [3,7,8], is only a small portion of the overall tertiary structural constraints in the T state that can take place in Hb (Fig. 1).

The effect of potent heterotropic effectors on the O2-affinity of β-semi-Hb, a non-cooperative, high-affinity R-state O2-carrier [23]. The O2 affinity of β-semi-Hb is reduced by as much as two orders of magnitude by tertiary structural constraints in the R state, which were imposed by the interaction with potent heterotropic effectors (IHP, L35, and a combination of IHP and L35), in the absence of the O2-linked homotropic quaternary transition, even at the physiological pH of 7.4. The O2 binding curve of stripped Hb with a cooperativity of KR/KT ≈30 [4,20] under the same conditions is also presented for comparison.

Monod et al. [3] formulated the MWC two-state concerted model of Hb on the basis of limited O2-equilibrium data available in 1965, before the discovery of potent allosteric effectors such as DPG [5]. It is, therefore, not surprising that the molecular mechanism of Hb allostery has been modified to the extended MWC/Perutz model [7,8] and now expanded to the Global Allostery model [4,20,21]. This new model, which incorporates both ligation-linked quaternary and effector-linked tertiary structural changes, is formulated primarily on the basis of the detailed quantitative analyses of more extensive oxygenation data obtained using the very conventional technique of O2-equilibrium measurements, albeit performed with higher precision and accuracy. Peculiar notions in the support/defense of the MWC/Perutz model, which are rather unique in the field of Hb research, need addressing. First, that the extended MWC/Perutz model [7,8,24] is sufficient to quantitatively explain the behavior of Hb under physiological conditions. Further, that any other finding obtained using synthetic effectors and/or beyond physiological pH range conditions and that do not conform to the MWC/Perutz model, are physiologically irrelevant and thus not worthy of serious consideration. These notions are quite contrary to the standard research methodology commonly used to elucidate enzyme mechanisms. We normally elucidate the molecular mechanism of an enzyme by examining its behavior in the widest possible range of experimental conditions using not only natural but also synthetic substrates, activators and inhibitors, regardless of the physiological conditions where it functions. The most fundamental question regarding the molecular mechanism of regulation/control of the O2-affinity in Hb can be elucidated only by examining the O2-binding behaviors of Hb in the widest possible range of experimental conditions rather than in a limited range of physiological conditions. We consider that the MWC/Perutz model [3,7,8] and its extension [24–26] are an abbreviated version of the Global Allostery model, which also accounts for the behavior of Hb under normal physiological conditions.

The physiological importance/significance of the interactions of R (oxy) Hb with heterotropic effectors that lower its O2 affinity (KR) is the hallmark of the Global Allostery model (Figs. 1B and 2). The preferential binding of an effector to the T-state, which is one of the tenets of the MWC model, is not quite as absolute as one has been led to believe. The affinities of most of heterotropic effectors toward deoxy (T) Hb are approximately >102-times higher than that to ligated (R) Hb at and above pH 7.4 (9–13). However, the affinity of the latter substantially increases and approaches that of the former in the slightly acidic physiological pH range (pH 7.0 → pH 6.6), as shown in Figs. 1B and 2 [4]. Recently the molecular structure of a complex of R (ligated) Hb with BZF, a potent allosteric effector, has been determined [27]. Bezafibrates have been known to bind to Hb at the interior cavity of T (deoxy) Hb [28], strengthening the inter-subunit interactions between two α1β1 and α2β2 dimers and shifting its allosteric equilibrium more toward the T state. However, in R (ligated) Hb they are bound to the E-helices of the α-subunits in a piggyback fashion on the surface of the molecule, altering the geometry of the distal heme environment. This is the first demonstration of the mode of action of heterotropic allosteric effectors on R (ligated) Hb, stereochemically influencing the ligand affinity of R (ligated) Hb. This proves further that allosteric effectors cannot only bind to both T (deoxy) but also R (ligated) states of Hb, differentially affecting KT as well as KR. One can amply demonstrate the physiological significance of the binding of heterotropic effectors to R (ligated) Hb by the following examples.

- (i) First, it has been reported that during high altitude adaptation, the intra-erythrocyte concentration of DPG increases by ∼50%, accompanied by substantial increases in P50 from 26.6 torr to 31 torr [29]. Hemoglobin is nearly saturated with DPG inside the erythrocytes at sea level. Therefore, any increases in the intra-erythrocyte concentration of DPG beyond the sea level should decrease the KT value only slightly and minimally affect the P50 value, according to the MWC/Perutz model [7,8]. The observed significant increases in P50 can be explained only by the following assumption: at increased concentrations of DPG, this effector begins to bind to R (oxy) Hb to lower the KR value significantly, even at the physiological pH, resulting in substantial increases in P50 to enhance O2 delivery to the tissues at high altitude.

- (ii) Secondly, the highly sensitive pH dependence of the O2-binding curves exhibited by Hb in the presence of several potent heterotropic effectors such as Cl−+ BZF + IHP (Fig. 2) [4,20] reminds us of the Root effect of some fish Hbs [30]. This behavior of Hb must result primarily from the extreme pH sensitivity of KR in the presence of the potent effectors (Figs. 1B and 2), by which the O2-affinity of R (oxy) Hb (KR) is reduced by as much as three orders of magnitude upon acidification. Such a mechanism may allow the fish oxy Hb in the presence of ATP, its effector, to release O2 into the swim bladder, even under extremely high hydrostatic partial pressure of O2 at deep sea, in order to adjust the buoyancy by local acidification. It is amazing to observe that such an extreme behavior can be mimicked in human Hb via heterotropic allostery in R (oxy) Hb.

- (iii) Thirdly, Hb under the maximal heterotropic allosteric constraint (curve at pH 6.6 in Fig. 2), where KR is reduced by as much as >1000-fold to a minimal value (KR=0.05 torr−1) by pH-sensitive interactions with heterotropic effectors [4,20], can mimic the O2-binding behaviors of Hb Kansas [14].

Thus, the binding of effectors to R (oxy) Hb, predicted by the Global Allostery model and ignored by the MWC/Perutz model, becomes significant in explaining physiological phenomena.

It has long been considered that the binding of various heterotropic effectors modulates the O2-affinity and cooperative function of Hb. The assumption has been that these effectors all made small perturbations on the essential cooperative behavior of the Hb molecule itself (Fig. 1A) [2,6–8,14,24–26]. It appears that the reverse is actually true from a global viewpoint (Fig. 1B) [4]. Now Hb can be viewed much more like a classic allosteric enzyme, in which the fundamental and strongest interactions are heterotropic. The cooperative (homotropic) behavior of the Hb molecule exerts a small perturbation on those heterotropic interactions of Hb (Fig. 1B).

The cooperativity of Hb (KR/KT>1) is generated by the differential tertiary structural constraints on T (deoxy) and R (oxy) states, leading to the differential modulation of both KT and KR [4,20,21]. These tertiary structural constraints are imposed by combined effects of both the ligand-linked, T/R quaternary structural changes (Fig. 1A) [3,7,8] and the effector-linked tertiary structural alterations (Fig. 1B) [4,20,21]. The latter play much more dominant roles in regulating KT and KR and consequently P50 as well as the cooperativity (KR/KT) and the Bohr effect (ΔP50/ΔpH). The molecular mechanisms of the cooperative process such as the two-state concerted model [3], the stereo-chemical model [7,8], the three-state model [6], the sequential model [31], and the molecular code model [32] deal with the processes of the release/formation of those tertiary structural constraints by the reversible ligation. They involve far more complex processes than previously assumed. The cooperative process of reversible O2-binding to Hb is not only accompanied by the reversible dissociation of effectors from/to T (deoxy) Hb, but also followed by the reversible binding to/from R (oxy) Hb, even under physiological conditions. In addition, both T (deoxy) and R (oxy) states have continua of tertiary structural constraints, culminating a series of KT and KR values. As such, they are still interesting to explore, but too complex to explain by such simplistic hypotheses dealing with the reversible process of ligation alone and to decipher by the techniques currently available. Furthermore, energetically speaking, the T/R quaternary-linked cooperative process of Hb is no longer the process of our primary interest, as they play lesser roles in the overall allostery of Hb (Fig. 1) [4,20,21].

It is, therefore, the time to focus our attention to the following questions:

- (i) how are the affinity and reactivity of the heme prosthetic groups of Hb regulated by the structural changes of the host protein (globin) under the heterotropic constraints, as illustrated in Fig. 3?

- (ii) here is the free energy of allostery, required to restore the high affinity/reactivity of the heme under unconstrained conditions of the R (ligated) state, stored in the protein?

Modifications of Hb by specific genetic engineering techniques have been widely employed in order to alter specific Hb properties. They have provided important information regarding structure–function relationships in Hb. However, once the critical and central role of the heterotropic interactions in regulation and control of the Hb functions is recognized, a new approach can be taken. Methods modifying the functional characteristics of Hb, which are more useful in specific physiological roles, may be derived from the alteration of the interaction mode of Hb with heterotropic effectors. This can be accomplished by chemical or genetic engineering methods designed to alter the structure of the effector-binding sites of Hb. For example, nature has accomplished this feat in fetal Hb. Fetal Hb, which has a lower O2 affinity than adult Hb in vitro, binds DPG less tightly than adult Hb due to a mutation at its DPG-binding site. Therefore, in the presence of DPG under physiological conditions, the O2 affinities of fetal and adult Hb are reversed, allowing the efficient transfer of O2 from the mother's blood to the fetal blood to accomplish the physiological role of fetal Hb. Alternatively, one could design and synthesize heterotropic effectors having different allosteric potencies and/or with or without preferential affinities for T (deoxy) Hb. A simple method to utilize ‘NO’ as a membrane-permeable, heme-specific allosteric effector to convert Hb to α-nitrosyl Hb having low affinity [33] has been perfected, in order to convert/rejuvenate old high-affinity ‘expired blood’ to a low-affinity blood, suitable for blood transfusion and as media for hypo-thermal surgery and hypo-thermal organ preservation [34–36].

The Global Allostery model [4,20,21] stresses the fundamental importance of the heterotropic interactions. They alter the tertiary structures of both T (deoxy) and R (oxy) Hb, leading to large-scale modulations of the O2 affinity (KT and KR), the cooperativity (KR/KT), and the Bohr effect (ΔP50/ΔpH) and thus explaining the allosteric functions of Hb from a global viewpoint.

Dedication and acknowledgements

The authors wish to dedicate this article in honor of the 20th anniversary of the memory of the untimely passing of Eraldo Antonini, friend and colleague. This work has been supported in part by a research grant, HL 14508 from the National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute.