Version française abrégée

La contrainte majeure qui affecte la production des céréales dans le Bassin méditerranéen est le manque d'eau. Le climat de cette région est bien connu pour ses précipitations erratiques et imprévisibles. Malgré ce caractère imprévisible, les études fréquentielles de ce climat ont permis d'identifier deux périodes de sécheresse principales. La première arrive à l'automne du semis, jusqu'au tallage. La seconde coı̈ncide avec le remplissage du grain. L'impact d'une sécheresse de fin de cycle sur la production des céréales a été largement étudié, alors que les effets d'un déficit hydrique précoce restent peu connus.

La sélection de plantes tolérantes à la sécheresse est considérée comme le moyen le plus efficace pour l'amélioration de ce caractère. Une meilleure compréhension des mécanismes impliqués dans l'adaptation des plantes pourrait faciliter l'amélioration de la tolérance. Cependant, ce caractère est complexe et résulte de la contribution concomitante de plusieurs facteurs, parmi lesquels figure le développement racinaire. Une large variabilité génétique a été observée pour plusieurs caractères racinaires, chez plusieurs espèces végétales. Leur intérêt dans l'amélioration de la tolérance à la sécheresse a été abondamment abordé. Néanmoins, la plupart des études ont été réalisées chez le blé, le maı̈s, l'avoine et le sorgho. Peu de travaux ont été réalisés sur l'orge, même si cette espèce est cultivée dans les régions méditerranéennes qui reçoivent le moins de précipitations et sont sans irrigation. De plus, les rares études menées ont porté sur la morphologie des racines adventives. L'impact d'un stress précoce (lors de l'installation de la plante) sur les racines séminales à différentes profondeurs du sol n'a pas été abordé chez cette espèce. En l'absence d'information sur la morphologie des racines séminales sous déficit hydrique précoce, l'objectif de notre travail est d'étudier les différences génotypiques pour plusieurs caractères racinaires à différentes profondeurs du sol, sous différentes conditions hydriques.

Pour ce faire, huit génotypes d'orge ont été cultivés sous conditions contrôlées dans une serre dans des cylindres en PVC de 60 cm de long, contenant un mélange de sable, de terre et de matière organique dans les proportions 8:1:1. Quatre traitements hydriques ont été appliqués : plantes bien arrosées (100 % de la capacité au champ (CC)), stress hydrique faible (75 % CC), moyen (50 % CC) et sévère (25 % CC). Les plantes ont été bien arrosées jusqu'au stade « deuxième feuille bien développée ». À ce stade, le stress a été appliqué par arrêt d'arrosage. Les mesures des caractères racinaires ont été réalisées au stade « quatre feuilles bien développées ». Ces mesures ont porté sur la longueur et le volume racinaires ainsi que sur le rapport des matières sèches racinaire et aérienne. Le volume racinaire a été évalué à trois profondeurs différentes (0–20, 20–40, au-delà de 40 cm). L'humidité du sol (exprimée en %) a également été évaluée à la fin de l'expérimentation pour les même profondeurs que le volume racinaire.

Des différences entre les génotypes ont été observées pour l'ensemble des caractères mesurés. Les traitements hydriques appliqués ont affecté significativement les caractères étudiés. L'interaction génotype × traitement hydrique est également significative, ce qui suggère que les génotypes ne répondent pas de la même manière au déficit hydrique. La longueur des racines séminales est peu affectée par un stress hydrique faible (75 % CC). Ce caractère diminue fortement à partir d'un déficit hydrique moyen (50 % CC). En fait, la longueur des racines diminue trois fois des conditions favorables jusqu'au stress hydrique sévère. Pour le volume racinaire, il n'y a pas de différences significatives dans la couche supérieure du substrat (0–20 cm). Dans la seconde couche, seul le stress sévère provoque une diminution de la valeur de ce caractère. Au-delà de 40 cm de profondeur, la diminution de la valeur du volume racinaire va de pair avec l'intensité du stress hydrique. À titre d'exemple, 90 % du volume racinaire sont confinés dans la couche supérieure du substrat sous déficit hydrique sévère, alors qu'en conditions favorables, on note une distribution répartie sur les trois couches du substrat. Contrairement aux deux premiers caractères, le rapport des matières sèches racinaire et aérienne augmente avec l'accroissement de l'intensité du stress.

Les différences génotypiques et les différences entre les traitements hydriques observées dans notre travail sont similaires à celles rapportées dans la littérature sur des racines adventives chez plusieurs espèces végétales. Plusieurs travaux ont également établi que les génotypes de l'espèce étudiée ne répondent pas de la même manière au stress hydrique. Notre étude souligne les différences de développement des racines séminales en fonction de l'intensité du stress. En effet, un déficit hydrique faible ou moyen affecte peu le développement de ces racines, alors que l'impact d'un stress sévère est beaucoup plus marqué, en bloquant la croissance. Cet arrêt de croissance serait engendré par la mort des apex racinaires et par la non-initiation de nouvelles racines latérales. L'augmentation du rapport des matières sèches racinaire et aérienne sous déficit hydrique est plus liée à la diminution de la production de la matière sèche aérienne qu'à celle des racines, sauf sous stress sévère, où nous avons observé une diminution des deux.

D'une manière générale, cette étude a montré l'existence d'une variation génotypique pour les caractères morphologiques des racines séminales chez l'orge sous déficit hydrique. Les génotypes ne répondent pas de la même manière au manque d'eau dans le sol. Ces différentes réponses ne sont pas liées à l'origine géographique des lignées. Une étude sur une collection plus large permettrait d'examiner ce lien entre la réponse des génotypes et leur origine géographique, comme il a été trouvé pour d'autres caractères morphologiques et physiologiques. Une étude anatomique mérite d'être menée et permettrait d'approfondir nos connaissances sur la réaction des racines séminales face à un déficit hydrique.

1 Introduction

Water shortage is the major constraint affecting cereal production in the Mediterranean Basin. The climate of this region is characterised by erratic and unpredictable precipitations [1]. Although drought may occur at any stage of cereal development in these areas, climatic frequency studies have identified two major periods when drought is most likely to occur [1,2]. The first occurs in autumn during the period from sowing to tillering. The second major drought period coincides with the grain-filling phase. Impacts of terminal water stress on cereals have been thoroughly investigated, while studies of early season drought are lacking. An early season drought may affect considerably yields through the limitation of tiller survival rate and number of kernels produced [1,3].

Selection of tolerant cultivars has been considered as an economic and efficient means to improve drought tolerance [4,5]. A better understanding of mechanisms of adaptation to water deficit and maintain of growth, development and productivity during stress periods would help the drought-tolerance breeding [4]. Nevertheless, drought tolerance is a complex trait resulting from the contribution of numerous factors. Among the several putative characters, water status parameters [6,7], carbon isotope discrimination [8,9], roots characters [3,10,11] are interesting traits for drought-tolerance evaluation.

The development of extensive root system contributes to differences between cereal cultivars for drought tolerance [5,12]. Genotypic variability has been found in many species for root characters [13–16], and their interests for drought tolerance improvement discussed [4,5,12]. Several works have studied root development mostly in wheat, maize, sorghum and oat. The scarce root development studies in barley have been done on adventitious roots under water-deficit conditions [10,11]. Moreover, these studies were performed at flowering stage. An appreciable genotypic diversity for root growth at early stages was reported in barley under favourable conditions or under other abiotic stress [14,17,18]. However, these reports cannot reflect the plant behaviour under harsh conditions prevailing in the Mediterranean Basin. There is limited insight into morphological traits of seminal roots in barley under drought, although this species is mainly cultivated without irrigation in arid and semi-arid regions. The comparison between adventitious and seminal roots in wheat showed that the two root types perceive and respond differently to drought stress and demonstrated the extreme sensitivity of seminal roots to water stress [19,20]. Other studies showed that damages caused to wheat seminal roots and seedlings depend more on the timing and severity of drought than on its duration [19–21]. Indeed, these works emphasised that severe drought, even during short periods, affects long-term growth of cereals plants. In addition, early water stress seems to damage the number of tillers and the number of grains per ear [1,19,20], which strongly reduces yield production in cereals [5,22].

The most studied traits were volume, length and number of seminal roots as well as the root-to-shoot dry matters' ratio. It was reported that the number of seminal roots is slightly or not affected by water deficit [19,20,23,24]. Other studies reported that this trait could not be used to discriminate cereal genotypes [13]. In contrast, volume and length of both adventitious and seminal roots were considered as efficient characters to evaluate genotype response to water stress [10,13,16,18–21,23,24]. All these works were performed on total root system. Limited studies have considered the response of adventitious roots at different soil layers. Similar investigations on seminal roots are lacking.

In the absence of any information on morphological traits of seminal roots in barley under water-deficit conditions, the major objective of this study is to examine the differences in some morphological traits of seminal roots at different soil layers among barley cultivars in response to the variation in the intensity of water deficit.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Plant material

Eight barley genotypes (Hordeum vulgare L.) from different geographic origins were used in this study. They included an Algerian landrace, one accession from the Italian germplasm and an improved variety from the Arabian Centre for Studies of Arid Zones and Drylands (ACSAD). The five other genotypes were improved varieties released by the ICARDA program (International Centre for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas) under Syrian conditions. The names and origins of these genotypes are reported in Table 1.

List of the barley genotypes used in this study

| Genotype | Type | Origin |

| 1 – Saida | Landrace | Algeria |

| 2 – ACSAD 176 | Advanced line | ACSAD (Syria) |

| 3 – Arizona5908/Aths/line640/3/Arizona5908/Aths/line640 | Advanced line | ICARDA (Syria) |

| 4 – CI08887/CI05-761/line640/A/4/Sask1766/Api Cell/3/Weeah | Advanced line | ICARDA (Syria) |

| 5 – Wislburger/Ahor1303 61/steptoe, Atares ICB89 H-0140-OAP | Advanced line | ICARDA (Syria) |

| 6 – Algerian selection plot 601/Sen‘S’ | Advanced line | ICARDA (Syria) |

| 7 – U.Sask. 1766/Api/Cell/3/Weeah/3/line 527/NK 1272 | Advanced line | ICARDA (Syria) |

| 8 – LO.94583 | Landrace | IAO (Italy) |

2.2 Experimental design and water conditions

The experiment was conducted, under glasshouse-controlled conditions, in the University of Tiaret (Algeria). Diurnal and nocturnal temperatures were maintained at 20 and 15 °C respectively and the relative humidity was 70%. The photoperiod was maintained at 15 h day−1, with a supplement of light of 85 W m−2.

A randomised complete block design was used with two blocks. In each water treatment, each genotype was represented by five plants. Seeds were put in Petri dishes for germination. After the emergence of the first leaf, the seedlings were grown in PVC cylinders, 60 cm high and 10 cm in diameter, and filled with a mixture of sand, soil and organic dry matter (8:1:1).

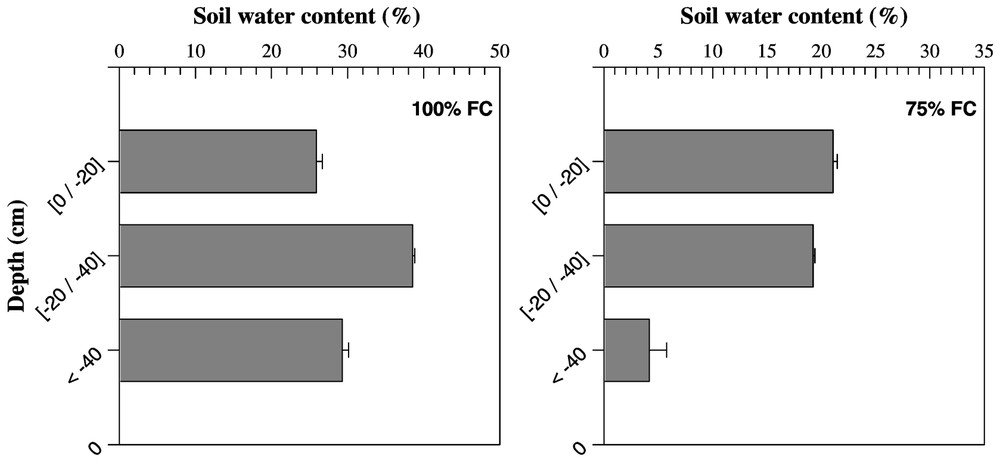

The plants were watered at the field capacity until the emergence of the second leaf. At this developmental stage, water was withheld to induce water deficit. The plants were submitted to four different water treatments at 100, 75, 50 and 25% of the field capacity (FC), hereafter considered as favourable conditions, low, moderate and severe water deficit, respectively. The measurements of soil humidity were performed when plants were at four fully developed leaves by weighing soil samples at plant harvest (i.e., the end of experiment) and reweighing them after drying at 105 °C during 24 h. Soil humidity was determined at 0–20, 20–40 and beyond 40 cm depth. The Measurements were done on five samples for each depth in each water treatment.

2.3 Measurements

Roots were washed in order to eliminate the potting mixture residue. In each water treatment, measurements were performed on ten plants. The length of seminal roots (in cm) was measured. Seminal root volume was evaluated at three depth layers (0–20 cm, 20–40 cm and more than 40 cm), according to the method of Musick et al. [25] by immersion in a graduate test tube and measure of the displaced water volume. Roots samples and aerial fresh samples were oven-dried at 80 °C for 48 h and weighed to determine the dry matter weight of each part. The ratio of root to shoot dry matters (RDM/SDM) was then calculated.

2.4 Statistical analyses

All the data were subjected to ANOVA using the GLM procedure of SAS (SAS Institute, 1987, Cary, NC, USA). Comparisons between genotypes, within each water treatment, were based on the Duncan test at 5% probability level.

3 Results

The profiles of soil water content for 10-cm depth increments in each water treatment are presented in Fig. 1. Differences in soil humidity were detected at the topsoil layer (0–20 cm). The reduction in soil water content in the upper soil layer between the control (100% of field capacity (FC)) and severe water deficit (25% FC) was significant. Major differences between water treatments were observed in the deepest layer. These differences are more pronounced between 100 and 25% FC treatments. The soil water content under severe stress was significantly lower than under the three other water treatments.

Mean values of soil humidity measured at three soil depths in four different water treatments expressed in percentage of field capacity. Bars represent standard error.

Genotypes differed significantly in all measured traits (Table 2). Detailed genotypic values are presented in Tables 3 and 4. There were significant differences between studied water treatments. The genotype by water treatment interaction was also significant for all characters (Table 2).

Mean square values and the significance of water treatment, genotype and their interaction effects on root traits measured on eight genotypes grown under four water treatments. Degrees of freedom (d.f.) are also displayed

| Trait | Water treatment effect (d.f.=3) | Genotype effect (d.f.=7) | Genotype×water treatment effect (d.f.=21) |

| Seminal root length | 8307.13∗∗∗ | 744.54∗∗∗ | 3933.7∗∗∗ |

| Root-to-shoot dry matters ratio | 0.34∗∗∗ | 0.27∗∗∗ | 0.58∗∗∗ |

| Seminal root volume | |||

| 0–20-cm layer | 34.32∗∗∗ | 12.75∗∗∗ | 30.52∗∗∗ |

| 20–40-cm layer | 11.04∗∗∗ | 11.54∗∗∗ | 26.81∗∗∗ |

| Beyond 40 cm | 3.04∗∗∗ | 26.59∗∗∗ | 15.82∗∗∗ |

∗∗∗ significant at P⩽0.001.

Mean values of seminal root length and root to shoot dry matters ratio measured on eight genotypes grown under different water treatments. Means indicated by different letters (within each water treatment) are significantly different (at 0.05 probability level) by the Duncan comparison test

| Genotype | Water treatment (% of field capacity) | |||||||

| 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | |

| Seminal root length (cm) | Root to shoot dry matters ratio (g g−1) | |||||||

| 1 | 20.6B | 52.6B | 59.3C | 64.0B | 0.39B | 0.17B | 0.14B | 0.10AB |

| 2 | 17.3C | 56.4A | 61.8B | 67.7A | 0.37B | 0.19A | 0.17A | 0.11A |

| 3 | 20.6B | 56.3A | 56.5D | 68.5A | 0.38B | 0.17B | 0.16A | 0.09B |

| 4 | 20.7B | 55.2A | 59.0C | 61.8C | 0.44A | 0.14C | 0.12C | 0.10AB |

| 5 | 25.2A | 55.1A | 58.2C | 55.4D | 0.35CD | 0.14C | 0.13C | 0.09B |

| 6 | 17.4C | 42.0D | 65.3A | 67.6A | 0.37B | 0.14C | 0.12C | 0.08B |

| 7 | 14.3D | 53.6B | 58.7C | 65.6AB | 0.30D | 0.13C | 0.12C | 0.11A |

| 8 | 20.1B | 49.6C | 57.2D | 66.1AB | 0.38B | 0.17B | 0.13B | 0.12A |

| LSD | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

Mean values of seminal roots volume measured at three soil depths on eight genotypes grown under different water treatments. Means indicated by different letters (in each soil layer and within each water treatment) are significantly different (at 0.05 probability level) by the Duncan comparison test

| Genotype | Water treatment (in % field capacity) | |||||||||||

| 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | |

| Soil layer 0–20 cm | Soil layer 20–40 cm | Soil layer beyond 40 cm | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0.60B | 0.60B | 0.50CD | 0.48C | 0.00B | 0.37B | 0.42B | 0.38B | 0.00 | 0.37B | 0.25C | 0.30B |

| 2 | 0.67A | 0.68A | 0.62A | 0.49C | 0.00B | 0.33C | 0.40B | 0.38B | 0.00 | 0.33C | 0.28B | 0.25C |

| 3 | 0.70A | 0.52C | 0.52C | 0.50C | 0.10A | 0.30C | 0.37B | 0.45A | 0.00 | 0.30D | 0.25C | 0.25C |

| 4 | 0.67A | 0.65A | 0.65A | 0.53B | 0.00B | 0.43B | 0.42B | 0.43AB | 0.00 | 0.43A | 0.28B | 0.28C |

| 5 | 0.73A | 0.65A | 0.48D | 0.58A | 0.15A | 0.37B | 0.45B | 0.20C | 0.00 | 0.37B | 0.20D | 0.25C |

| 6 | 0.55B | 0.57B | 0.58B | 0.58A | 0.10A | 0.35BC | 0.60A | 0.35B | 0.00 | 0.35B | 0.25C | 0.30B |

| 7 | 0.40C | 0.55BC | 0.60AB | 0.58A | 0.10A | 0.43A | 0.65A | 0.37B | 0.00 | 0.43A | 0.30A | 0.33B |

| 8 | 0.35C | 0.53C | 0.45D | 0.55B | 0.00B | 0.40AB | 0.45B | 0.50A | 0.00 | 0.40A | 0.28B | 0.40A |

| LSD | 0.064 | 0.034 | 0.041 | 0.022 | 0.070 | 0.040 | 0.071 | 0.062 | – | 0.030 | 0.022 | 0.049 |

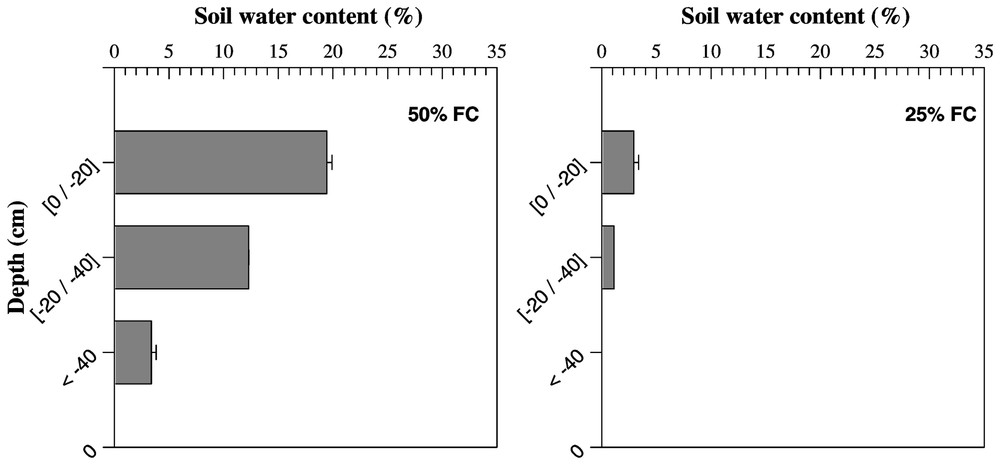

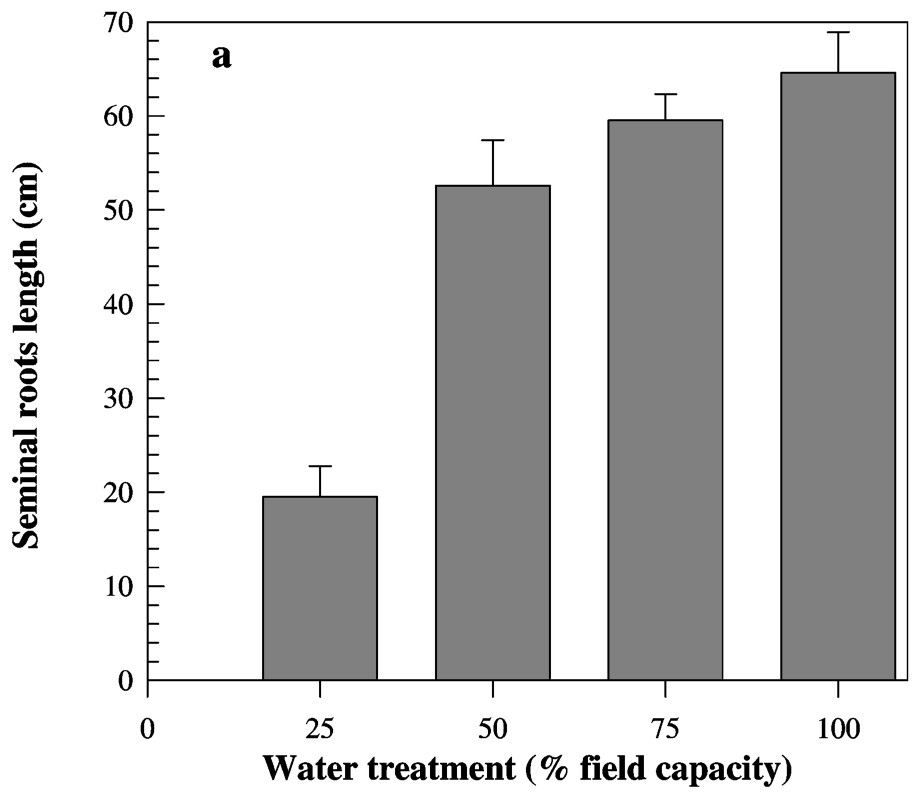

Measured traits were significantly affected by water treatments. Mean seminal root length value was near 65 cm at 100% FC. This value decreased slightly with the increase of water stress intensity (Fig. 2a). Moreover, no significant difference between 100 and 75% FC treatments was observed. In contrast, when water deficit went below 50% FC, seminal root length decreased strongly and reached a value of 19.5 cm at 25% FC (Fig. 2a). In fact, the seminal root length decreased more than three times from 100% to 25% FC. Seminal root volume was studied in three soil layers (0–20 cm, 20–40 cm and beyond 40 cm) for each water treatment. At the topsoil layer (0–20 cm), there were no significant differences between water treatments for seminal root volume (Fig. 2b). In the second soil layer (20–40 cm), no significant differences were found between favourable conditions and both low and moderate water deficit. However, the value of root volume in this soil layer fell in completely below 50% FC (Fig. 2b). In the third soil layer (beyond 40 cm), the root volume decreased slightly under low water deficit and strongly when water became scarcer (Table 4). Indeed, roots did not grow deeper than 40 cm. Under both 100% FC and low water deficit conditions, the root volume was distributed over the three studied soil layers. Moderate water deficit induces a decrease of root volume in the deeper layer and an increase of values of this trait in the upper layer. At 25% FC, 90% of roots were confined in the topsoil layer and did not grow in the deepest layer (Fig. 2c).

Mean values of seminal root length (a) and volume (b) measured on eight barley genotypes cultivated under four water treatments. Seminal root volume was measured at three soil layers.

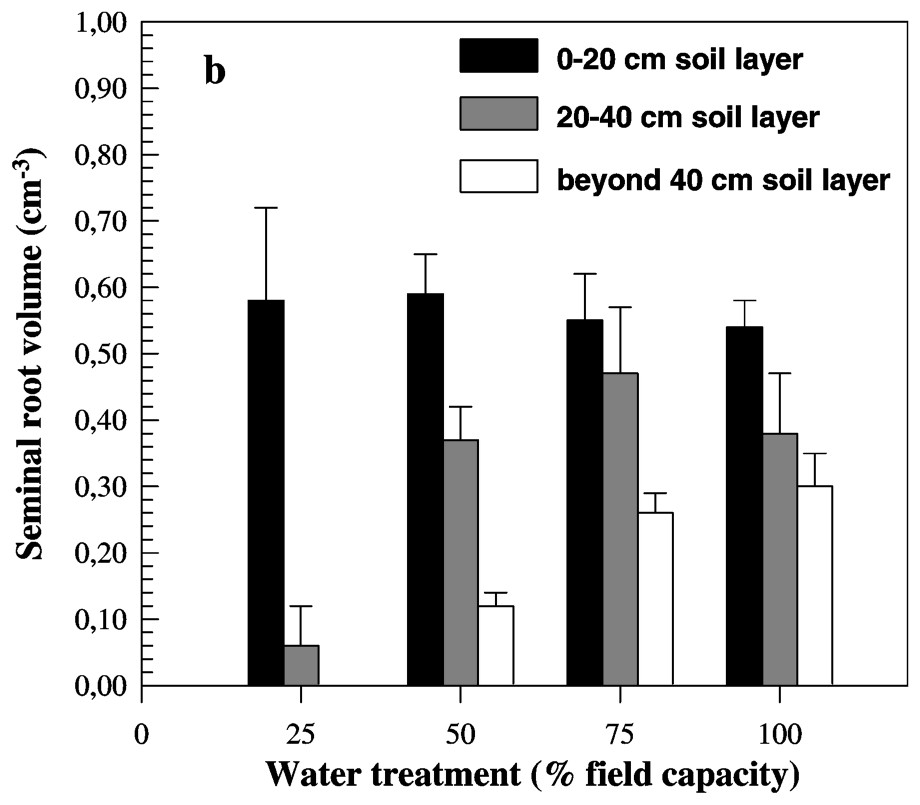

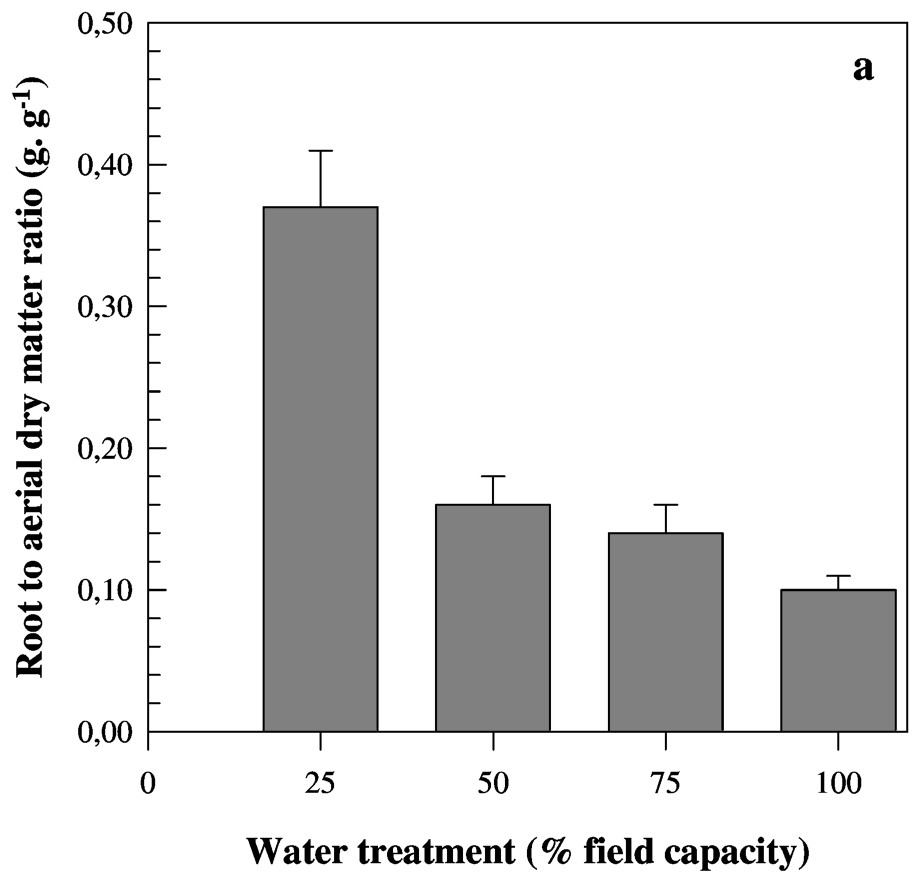

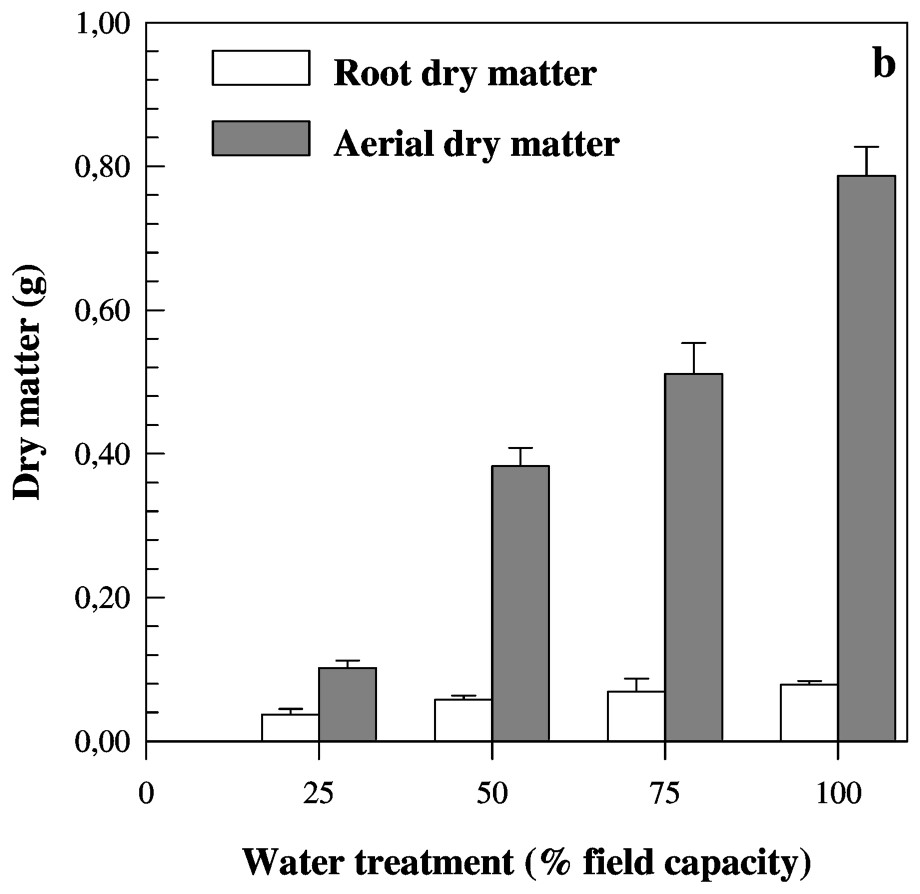

In contrast to the former traits, root to shoot dry matters ratio (RDM/SDM) increased when soil water decreased (Table 3). This trait increased nearly four times from favourable to severe water conditions.

A large genotypic variability was noticed for all measured traits. For both root length and volume, globally and as described before, there was a slight increase of trait values followed by a strong one below 50% FC treatment (Tables 3 and 4). Nevertheless, the studied genotypes did not present similar behaviour in response to water deficit. The genotypic values of measured traits are presented in Tables 3 and 4. For roots length, genotypes 3, 2 and 6 showed the highest values, whereas genotype 5 exhibited the shortest seminal roots under favourable conditions. Inversely, while genotype 5 presented the longest roots, genotypes 7, 2 and 6 have the shortest ones under severe water stress. The root length of genotype 5 did not vary from favourable to moderate stress, but decreased under moderate stress conditions (i.e., 50% FC), and decreased more than twice from favourable to severe water conditions. The difference observed for this trait on genotypes 7, 2 and 6 was more marked. The root length under 100% FC was 4.6 (genotype 7) and 3.9 (genotypes 2 and 6) higher than under 25% FC. In contrast to the majority of genotypes where a strong decrease of values was noted below 50% FC, genotype 6 (see Table 3) seems to respond early to water deficit. This line which presents the highest value at 75% FC showed the lowest root length at 50% FC (Table 3). For RDM/SDM, the lowest values were observed under favourable conditions and genotypes were slightly different. Genotypic differences were more marked, especially under severe water deficit. The RDM/SDM was 4.63, 4.40 and 4.22 higher under severe water stress than under favourable conditions for genotypes 6, 4 and 2, respectively. The lowest difference between the two water treatments was found for genotype 7.

4 Discussion

Significant differences were observed between studied water treatments (Figs. 2 and 3). Similar differences were already reported for several species on seminal and on adventitious roots [10,11,26–29]. Most of these works have also found significant interaction between water treatment and genotype, which mirrored differential responses patterns to increasing water stress. These results are confirmed in our study (Table 2).

Mean values of root to aerial dry matter ratio (a) and roots and aerial dry matter (b) measured on eight barley genotypes cultivated under four water treatments. Bars represent standard error.

A large genotypic variation was observed here for all studied root traits (Tables 3 and 4). These results confirm the broad variability found for morphological traits in seminal [20,23,30] and adventitious roots [15,28,31,32]. All these studies were done in wheat, maize or sunflower. The few studies performed in barley on adventitious roots under water stress [10,11] or on seminal roots under favourable conditions [33,34] also observed genotypic variability. Our results emphasised the existence of appreciable genotypic differences in seminal roots traits in barley grown under water-deficit conditions (Tables 3 and 4).

Seminal roots' length was affected by the decrease in soil water moisture. This decrease is slight under low and moderate water stress. In contrast, the root length is strongly affected under severe water-stress conditions (Fig. 2a). Several studies have already reported the effect of water stress on adventitious roots length [3,27,29,35,36]. The few studies performed on seminal roots also noticed the decrease of root length under water stress [18–20]. However, all these studies have been done on wheat or oat. The scarce works on barley were realised on adventitious roots [10,11]. Seminal roots were also studied under acid and acid/aluminium stress [17] or under favourable conditions in barley [33] or in comparison with other cereals [13]. This latter work emphasised the superiority of barley compared to other cereals in seminal root expression.

Root volume was strongly affected by water stress (Fig. 2b). Similar trends were observed on adventitious roots of wheat [27–29,36] and of barley [10,11]. Most of these studies have also noticed that root volume was not significantly affected in topsoil layer, but strongly decreased in deeper layers. These results were confirmed here. Nevertheless, the severity of stress has an additional impact on this trait, which was not studied in the cited works. Our results showed that low and moderate water treatments affect more slightly root volume in top and middle soil layer than expected (Fig. 2b). In contrast, under severe water stress, there were no roots in the deepest soil layer (Table 4). Indeed, more than 90% of roots were confined in the topsoil layer confirming previous report [28]. This latter study showed that 81% of roots of wheat genotypes cultivated under water stressed conditions were distributed in the 0–30-cm topsoil layer. A significant decline in root volume under early-season drought in deep soil layer was observed in durum wheat [3]. However, the decline observed in this latter work is quite small, whereas our results showed a strong decrease of root volume in the deepest layer. The difference was probably due to the induced water stress between the two works, suggesting that root growth depends on the intensity of water stress. The soil structure and composition could also contribute to the difference observed between the two studies.

Several works have studied the effect of stress duration on adventitious roots [10,27,37]. Other studies demonstrated that the seedling stage is more important than the duration of the stress when water stress occurs [19]. The root growth is dependent on both stress severity and timing [18,19,21]. The extreme sensitivity of seminal roots to water deficit was probably caused by the absence of cuticle that could protect against water evaporation [38]. Due to the death of existing apices and no initiation of new lateral roots [18,26] under severe water stress, seminal roots cease to grow [39]. Significant differences were found between water treatments for RDM/SDM (Table 2). An increase in values corresponding to this trait from favourable conditions to severe water deficit was found (Table 3). These results were expected and confirm those reported for several other species [10,11,27,29,36,37]. This ratio was higher under drought conditions than under well-watered conditions, due to reduced shoot growth rather than root growth [3,18], as presented in Fig. 3b. Under severe water deficit, both root and shoot dry mass production are reduced, as described in previous reports [18,39].

A differential genotypic response was observed here. Nevertheless, these differences are not related to the geographic origin. In fact, studied genotypes have been released under harsh Mediterranean conditions. Mid-East genotypes have been reported to respond differently from those of North Africa for water status parameters [40], carbon isotope discrimination [9], gas exchange [41], and root characteristics [10,29]. It could be interesting to study seminal root traits in a large collection of genotypes from different geographic regions.

In conclusion, an appreciable genotypic difference for seminal roots traits was observed in this study. A differential impact of water stress on roots was noted. Seminal root characters were affected by water stress and the impact of water deficit on these traits is related to the intensity of stress. It seems that the severe water stress causes the death of apices, which limits root growth. Anatomical approaches of seminal roots under severe water deficit may help to understand the changes induced by water deficit or operated by plants in response to this stress.