1 CRH coordinates the neuroendocrine stress response

The discovery of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) as a novel hypothalamic factor controlling the release of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) derived peptides in 1981 was a major breakthrough and has significantly contributed to our understanding how the organism is able to maintain its homeostasis in response to stress [1]. The neuropeptide CRH is the key switch controlling the activity of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical (HPA) system [2].

Human CRH is synthesized as a prepro-peptide of 196 amino acids containing a N-terminal signal peptide of 24 amino acids. Proteolytic processing of the precursor accompanied by amidation of its carboxy-terminal isoleucine residue results in the mature and biological active form composed of 41-amino acids [3]. High densities of CRH-immunoreactive neurons are found in the anterior and medial-dorsal parvocellular portion of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus from where these neurons project via the external zone of the median eminence to the anterior pituitary. Upon exposure to physical or psychological stressors, these neurons secrete CRH into the hypophysial portal vasculature. Subsequent activation of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type 1 (CRH-R1) stimulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and other POMC derived peptides from pituitary corticotrophs into the circulation [1]. About 50% of the medial-dorsal parvocellular CRH containing neurons responsible for ACTH secretion also express arginine vasopressin (AVP). AVP synergizes with CRH and is capable to potentiate the effects of CRH on the release of ACTH from the anterior pituitary [4–6]. The activation of the HPA system culminates in the synthesis and secretion of glucocorticoids – cortisol in primates or corticosterone in rodents – from the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex into the bloodstream what allows them to act on many different cell types throughout the body preparing the organism for acute reactions to stress (Fig. 1). The effects of ACTH on the secretion of the mineralocorticoid aldosterone are rather weak.

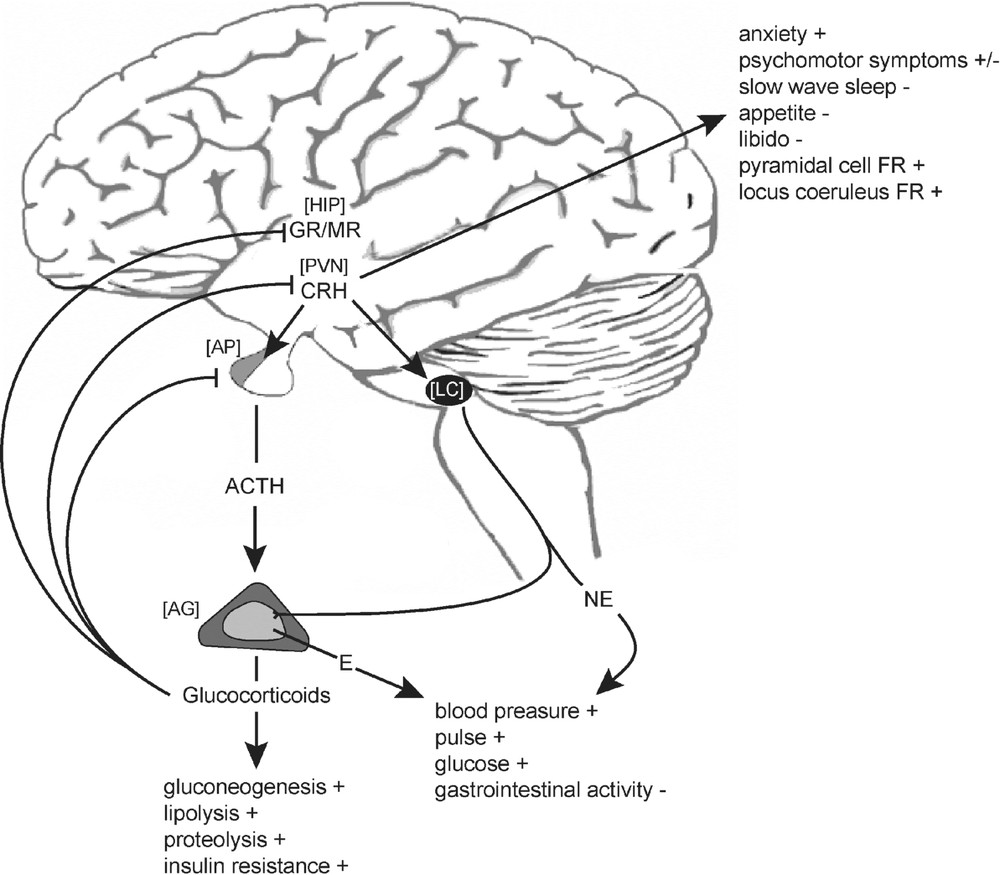

Schematic representation of CRH mediated endocrine, autonomic and behavioural response to stress. ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; E, epinephrine; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; NE, norepinephrine; AG, adrenal gland; AP, anterior pituitary; HIP, hippocampus; LC, locus coeruleus; FR, firing rate.

To restore or maintain homeostasis, cortisol and corticosterone interfere with a plethora of physiological functions. Corticosteroids govern energy mobilizing processes such as glycogenolysis, proteolysis and lipolysis and they suppress immune and reproductive functions whereas they enhance cardiovascular drive. Furthermore, corticosteroids influence emotions and cognitive processes, such as learning and memory and they play an important role in modulating fear and anxiety-related behaviour [7–10]. Glucocorticoid hypersecretion is implicated as a major deleterious factor in the process of aging and is known to accompany numerous long-term metabolic, affective and psychotic disease states [11,12]. Hence, blood corticosteroid levels are tightly regulated by an endocrine negative feedback mechanism involving both rapid and genomic actions at the pituitary and multiple sites in the brain decreasing the secretion of CRH and ACTH, respectively (Fig. 1) [8,13].

2 CRH acts as a neurotransmitter modulating neuronal activity

The anatomical distribution of CRH in the brain suggests that this peptide not only acts as a key neuroendocrine stress mediator, initiating activation of the HPA system, but also modulates neuronal activity, acting as a neurotransmitter and neuromodulator. CRH-containing neurons have been found throughout the central nervous system (CNS): olfactory bulb, central nucleus of the amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, nucleus accumbens, supraoptic, medial preoptic and periventricular preoptic nuclei, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, periaqueductal grey, raphe nuclei, lateral tegmental nucleus, parabrachial nucleus, cuneiform nuclei, locus coeruleus, medial vestibular nucleus and dorsal vagal complex [14,15]. The hypothalamic CRH system is important for modulating endocrine and metabolic responses to stress, while the amygdala, in concert with the other extrahypothalamic limbic regions mediates the behavioural responses to stress [14,16,17]. Accordingly CRH has been shown to modulate a multitude of behavioural traits including learning and memory, food intake, arousal, startle and fear responses, general motor activity and sexual behaviour [18,19].

In its dual capacity, CRH integrates hormonal and neuronal mechanisms by acting both as a secretagogue for ACTH release from the anterior pituitary and as an extrapituitary peptide neurotransmitter modulating synaptic transmission and regulating ionic currents in various brain regions [17,20]. CRH release from nerve terminals is stimulated in a calcium-dependent manner by potassium-induced depolarization or in a neurotransmitter-stimulated fashion, e.g., via glutamate, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), acetylcholine or norepinephrine [21–24].

During exposure to stress, CRH can be secreted directly from nerve terminals located in the hippocampus influencing neuronal properties. Application of CRH into the hippocampus exerts a profound action on hippocampal neuronal activity. CRH inhibits for instance the slow afterhyperpolarizing potential and spike frequency accommodation, an effect that would augment excitability [25–27]. CRH has been shown to enhance R-type voltage-gated calcium channels in neurons of the central amygdala [28] and it increases the amplitude of CA1 population spikes evoked by stimulation of the Schaffer collateral pathway [29]. In vitro CRH has been shown to increases firing rates of serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus and directly activates noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus [30,31]. Liu and colleagues demonstrated that CRH modulates excitatory glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the central amygdala (CeA) and the mediolateral nucleus of the lateral septum (MLNLS). Interestingly, CRH exerts opposing actions in these nuclei: in the CeA, CRH represses excitatory glutamatergic transmission, whereas in the MLNLS, CRH causes a facilitation of glutamatergic transmission [32]. Furthermore, excitatory glutamatergic transmission is potentiated via a CRH receptor type 2 (CRH-R2)-dependent modulation of NMDA transmission in dopaminergic neurons. This effect has been shown to be dependent on the CRH-binding protein (CRH-BP) and activation of the phospolipase C (PLC) – protein kinase C (PKC) pathway [33].

Besides synaptic plasticity in terms of LTD and LTP, CRH also influences neuronal differentiation, maturation and survival. Recently it has been shown that CRH contributes to processes involved in maturation of neuronal circuitries by modulating dendritic differentiation in the developing hippocampus [34,35]. Similar observations have been made in vitro using immortalized catecholaminergic neurons and Purkinje cells, where CRH triggers dendritic outgrowth and differentiation [36,37]. The early-life administration of excess CRH, which resembles the effect of early-life stress, results in progressive hippocampal cell loss and dysfunction [38,39]. These findings are in accordance with several studies demonstrating CRH as a mediator of cell death [40,41]. However, the role of CRH in the context of these processes remains controversial, since several lines of evidence exist that CRH also exhibits neuroprotective properties [42–44].

3 The diversity of CRH-related neuropeptides and their cognate receptors

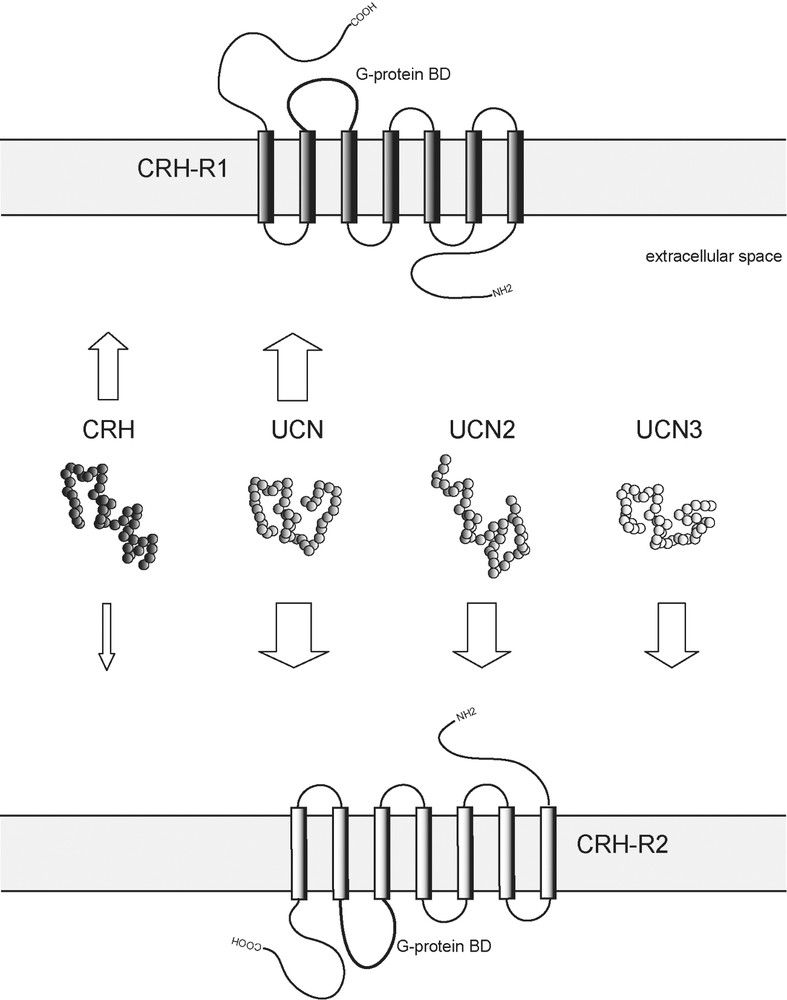

Considering the diverse actions coordinated by CRH and CRH receptors in neuroendocrine, autonomic and behavioural response to stress, it is not surprising that the CRH family of neuropeptides and their respective receptor–effector system has developed a high level of complexity. In mammals, the family or CRH-related neuropeptides consists to date of four members: CRH, urocortin (UCN), and the recently discovered, more distantly related peptides urocortin 2 (UCN2) and urocortin 3 (UCN3), defining a novel branch within the family (Fig. 2) [1,45,46]. These peptides are distributed throughout many stress-sensitive central structures and numerous peripheral tissues [47].

Mammalian family members of CRH-related neuropeptides and their receptors. Arrows represent ligand–receptor interactions. The thickness of arrows reflects relative binding affinities. CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; UCN, urocortin; UCN2, urocortin 2; UCN3, urocortin 3; CRH-R1, corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type 1; CRH-R2, corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type 2; G-protein BD, G-protein binding domain.

The biological activity of CRH-related peptides is mediated via two G protein-coupled heptahelical transmembrane receptors, CRH receptor type 1 and 2 (CRH-R1 and CRH-R2). CRH-R1 is predominantly expressed in the brain and pituitary, whereas CRH-R2 expression is limited to particular brain areas and to some peripheral organs. Furthermore, several splice variants of CRH receptors exist showing also a tissue specific distribution. In addition to their specific tissue distribution, CRH receptors exhibit distinct pharmacological properties and consequently also different physiological functions [47,48]. They are involved in modulating endocrine, autonomic and behavioural responses to stress, as well as a variety of peripheral (e.g., cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and immune) activities. CRH and UCN are bound by both CRH receptors. CRH is relatively selective for CRH-R1 over CRH-R2 displaying an almost 10-fold higher affinity for CRH-R1. Compared to CRH, UCN has an approximately 40-fold higher affinity for CRH-R2 and a 6-fold higher affinity for CRH-R1. UCN is able to mimic many of the effects of CRH, such as a high ACTH secretagogue potency. CRH and UCN are bound by the CRH binding protein (CRH-BP) with equal or greater affinity than by CRH receptors. CRH-BP further modulates the neuroendocrine and synaptic activity of CRH and UCN in the brain and pituitary [49]. UCN3 and UCN2 are selective, high-affinity ligands for CRH-R2 with no activity towards the CRH-R1. The affinity of CRH-related peptides for the CRH-R2 can be ranked as follows: UCN UCN2 UCN3 ≫ CRH (Fig. 2) [50].

The binding of CRH receptor ligands to the extracellular domain transforms CRH receptors in an active state thereby increasing their affinity for G-proteins. Depending on the localization and co-expression, CRH receptors can couple to multiple G-proteins. Stimulation of adenylate cyclase, accumulation of cAMP and activation of PKA as well as the activation of other second messengers like inositol

4 Dysregulation of the CRH system in depression

Impairments in the physiological responses to stress have been associated with various diseases, such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and neurodegenerative disorders. Therefore, the investigation of the mechanisms underlying the stress response could be extremely helpful to understand the etiologic basis of stress-related disorders and support the development of improved treatments.

Since the introduction of the first antidepressants, monoamines have been the major focus of biomedical research in terms of depression. A second line of intense investigation relates to the HPA system, since hyperactivity of the HPA system is one of the most prominent findings in patients with major depression [53]. Depressed patients display elevated levels of circulating ACTH and cortisol due to impaired corticosteroid receptor feedback [11]. CRH levels are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of affected subjects [54] and will be decreased again after successful drug treatment [55]. CRH expression in the hypothalamic PVN is increased [56] and CRH binding in the prefrontal cortex of depressed patients who committed suicide is diminished, which can be interpreted as an adaptive downregulation in response to CRH hypersecretion [57]. Additionally, the number of neurons co-expressing CRH and AVP is increased in the hypothalamus of depressed patients [58]. Finally, various hormonal challenge tests are out of balance in depressed patients, likewise pointing to a disturbed HPA system regulation [59–61].

Another line of evidence implicating HPA hyperactivity in depression comes from animal experiments of excess CRH. Both, the direct application of CRH into the CNS and the overexpression of CRH in transgenic mice results in phenotypic alterations strikingly resembling symptoms observed in patients with major depression including increased anxiety and arousal, decreased appetite and weight, altered sleeping behaviour and decreased sexual activity [62,63].

5 Genetically engineered mouse models dissect the CRH system

The ability to generate mice with defined, heritable genetic mutations has facilitated and fostered the study of many biological processes, from embryogenesis to behaviour. Genetically engineered mice are becoming increasingly important as research tools in studying psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric disorders are multifactorial diseases where involved genes are difficult to identify. Thus, it is rather unrealistic to expect the development of a model representing a ‘depressed’ mouse. However, many psychiatric disorders are associated with intermediate phenotypes that can be modelled and studied in mice, including physiological or morphological changes in the brain and behavioural traits. Depression, for instance, is behaviourally characterized by increased anxiety, behavioural despair, and altered patterns of activity, sleep and eating – traits that are accessible in mice. In the moment a dysfunctional system has been connected to a psychiatric disorder, mice will be a valuable tool in dissecting complex interactions and of major benefit in the identification of additional candidate genes and potential therapeutic targets – in this regard, the CRH system is one of the most relevant examples where numerous mouse mutants have been generated during the past decade [63–65].

The first attempt to approach genetically the CRH system has been a transgenic mouse model of CRH overproduction (CRH-Tg) in order to examine effects of chronic CRH excess [66]. In this mouse model, CRH hypersecretion has been reported primarily in regions of the brain that normally express CRH. CRH overproduction in the CNS leads to severely elevated ACTH and corticosterone levels. Consequently, CRH-Tg mice display a striking physical phenotype that resembles Cushing's syndrome. CRH-Tg mice show HPA hormone responses to stress that are delayed and attenuated, suggesting that chronic HPA activation desensitizes the HPA system to further stress-dependent stimulation [67]. Behaviourally, CRH overproduction leads to hypoactivity in novel environments and enhanced anxiety-like behaviour in several anxiety paradigms [68–70]. Furthermore, these mice display a decrease in motor function and a profound learning deficit [69,71]. Recently, another transgenic mouse model of chronic CRH overexpression has been developed and analysed. These mice, displaying slightly elevated ACTH and 5-fold increased corticosterone levels, develop a Cushing syndrome-like phenotype at the age of 5–6 months. Apart of slight deficits in locomotion, these mice show no alterations in response to stress or in terms of anxiety-related behaviour compared to wild-type littermates [72].

The generation of CRH knockout mice added further to the understanding of the physiologic and pathologic roles of CRH. CRH-deficient mice are viable and grossly indistinguishable from their wild-type littermates, but exhibit a markedly impaired corticosterone response to many types of acute stressors [73]. However, the stress response is not completely absent in CRH knockout mice, suggesting compensatory mechanisms involving other ACTH secretagogues such as AVP or catecholamines to maintain a stress response in the absence of CRH [74,75]. Completely unexpected was the observation that CRH-deficient mice exhibit similar measures of anxiety as their wild-type littermates in different anxiety paradigms. CRH receptor 1 (CRH-R1) antagonist studies in these mice suggest that another CRH-like molecule is acting or compensating for the lack of CRH to mediate some of the behavioural responses normally attributed to CRH [76].

Two mouse lines deficient for the CRH-R1 have been generated independently to characterize its function in anxiety-related behaviour and neuroendocrine control of HPA system activity [77,78]. CRH-R1, expressed in the brain and on anterior pituitary corticotrophs, mediates CRH signalling resulting in ACTH secretion. As predicted, CRH-R1-deficient mice exhibit a significantly impaired stress-induced HPA system activation and a marked corticosterone deficiency, similar to CRH knockout mice. However, unlike the CRH knockout mice, the CRH-R1-deficient mice exhibit decreased anxiety-like behaviour under basal conditions and following alcohol withdrawal.

Three independent mouse lines deficient for CRH-R2 have been generated, displaying significant differences in both the endocrine and in particular in the behavioural phenotype [79–81]: whereas Coste et al. found no differences in anxiety-related behaviour, both Bale et al. and Kishimoto et al. detected significant increases in anxiety-like behaviour in their CRH-R2 mutants, although Kishimoto only in male CRH-R2 knockout mice. CRH-R2-deficient mice display normal basal levels of ACTH and corticosterone, but an increased endocrine HPA activity in response to stressful stimuli. These results suggest an important role for CRH-R2 in regulating HPA system homeostasis, probably counterbalancing CRH-R1-mediated effects on ACTH and corticosterone release.

To investigate HPA system regulation in the absence of functional CRH receptors, mice deficient for CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 were generated. Double mutants are viable, fertile and indistinguishable from wild-type littermates, suggesting that mammals not necessarily need a functional CRH system for survival. However, the endocrine effect is recapitulated by the functional loss of CRH-R1 in these mutants. CRH-R2 neither compensates for CRH-R1 deficiency nor exacerbate the CRH-R1-dependent impairment of the HPA system function [82,83]. Testing for anxiety-related behaviour revealed a sexually dichotomous phenotype. Female double mutants display less anxiety-related behaviour, while male double mutants showed more anxiety-like behaviour compared with female double mutants [83].

Gene targeting of the CRH family member UCN discovered its previously unknown function in hearing [84]. As in the CRH-R2 mutants, the data on anxiety-related behaviour is conflicting in two different UCN knockout mouse lines generated. Wang and colleagues reported normal anxiety-like behaviour and autonomic responses, whereas Vetter and co-workers observed an increase in anxiety-related behaviour [84,85].

The CRH-BP plays in important modulatory role by regulating levels of free CRH and UCN in the pituitary and CNS. Three mouse models of CRH-BP overexpression and deficiency exist. To test the role of chronic elevation of secreted pituitary CRH-BP in the HPA system, Burrows and colleagues specifically overexpressed CRH-BP in the anterior pituitary [86]. Basal plasma concentrations of corticosterone and ACTH are unchanged, and a normal pattern of increased corticosterone and ACTH was observed after restraint stress. However, CRH and AVP mRNA levels in the transgenic mice are increased to compensate for the excess CRH-BP. The transgenic mice exhibit increased activity in standard behavioural tests. The ubiquitous and ectopic overexpression of CRH-BP resulting in chronically elevated plasma levels of CRH-BP had minor impact on HPA system regulation but induced sexually dimorphic weight gain [87]. CRH-BP deficient show normal function of the HPA system but decreased anxiety-like behaviour [88].

In conclusion, the presented mouse models have uncovered a wealth of information on the individual role of CRH related molecules in view of HPA system control and anxiety-like behaviour. None of these mouse mutants can be regarded as a proper model resembling human depression, but each of them has provided important insights into the regulation and compensatory changes within a physiological system that is affected in major depression, and thus provides clues to new targets for anti-depressant drugs.

6 The CRH system is involved in stress-induced alcohol drinking

Alcoholism is a complex disorder in which genetic variables are thought to interact with environmental factors producing and individual risk of alcohol abuse and alcoholism [89,90]. A growing body of evidence suggests a strong impact of genetic factors on individual differences in alcohol self-administration [91,92]. In addition to these genetic factors, the history of alcohol exposure can produce biochemical and behavioural changes that may influence alcohol consumption and preference [93]. Studies in humans and laboratory animals suggest that stressful life events and maladaptive responses to stress influence drug abuse, e.g., alcohol drinking and relapse behaviour [94]. Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying stress-induced alcohol drinking and relapse behaviour still remain to be elucidated, but recent studies suggest a major impact of the CRH system in these processes [95]. Le and colleagues demonstrated a contribution of CRH to stress-induced relapse to alcohol seeking via its action at extrahypothalamic sites [96,97]. Considering the described neuromodulatory properties of CRH, it is likely that the effect of CRH on the behavioural consequences of drugs of abuse is mediated through the interaction with other neurotransmitter systems. For example, during withdrawal and relapse phases, CRH may interact with the norepinephrine system to mediate aversive effects of drug withdrawal and stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking [95,98]. Repeated exposure to drugs of abuse induces adaptations in neuronal circuitries involved in stress response including the hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic CRH system [99]. During the initiation and maintenance phases, psychostimulants activate the HPA system in a CRH-dependent fashion, resulting in the release of corticosteroids. Corticosteroids in turn stimulate dopaminergic transmission in mesolimbic pathways that appear to enhance drug self-administration [100]. Furthermore, a high rate of comorbidity between mood disorders, in particular major depression, and alcohol abuse has been observed [101–103].

Mice lacking a functional CRH-R1 [77] represent a useful animal model to address the question whether a dysfunctional CRH system influences the individual vulnerability for alcohol drinking. CRH-R1 knockout mice and wild-type littermates did not differ in the intake or preference of alcohol when analysed under stress free housing conditions in a two-bottle free-choice paradigm. After a habituation period of eight weeks to 8% ethanol versus water, voluntary alcohol consumption of mutant and wild-type mice was monitored during and after repeated stress. Initially the mice were repeatedly exposed to a social defeat stress as a severe psychological stressor [104]. During and immediately following repeated social defeat stress, no difference in alcohol intake was observed in both genotypes as compared to baseline drinking. However, three weeks after the repeated stress episodes, the voluntary alcohol intake in the knockout mice was markedly increased, whereas it remained unaltered in the wild-type mice. During a second period of repeated stress, the mice were subjected to the forced swimming paradigm on three consecutive days. Forced swimming is predominantly a physical stressor, but also has an emotional component [105]. During the stress period, CRH-R1 knockout mice slightly decreased alcohol drinking, but this decrease was statistically not significant as compared to baseline alcohol consumption. However, after about three weeks, the knockout mice started again to progressively increase their alcohol intake. This post-stress alcohol intake of CRH-R1 mutant mice was significantly higher than that of the wild-type littermates. Enhanced alcohol intake in mutant mice was long lasting and was still present six months after the second period of stress episodes (Fig. 3). Control mice of both genotypes that had continuously free access to alcohol over three months without receiving the two sets of repeated stressors showed no changes in alcohol intake over time.

Long-term voluntary alcohol consumption in CRH-R1 knockout (white) compared to wild-type (black) mice. The bars represent mean alcohol intake per month. Repeated episodes of psychological and physical stress are indicated by arrows.

In summary, these results indicate that the CRH system that mediates, endocrine, autonomic and behavioural response to stress plays a role in control of long-term alcohol drinking. In mice lacking a functional CRH-R1, stress lead to enhanced and progressively increasing alcohol intake. Intriguingly, this behavioural change in alcohol drinking was not observed during or immediately after the stressful events, but it developed gradually over several weeks and lasted throughout their lifetime, even when the animals were not confronted with any further stressful experience (Fig. 3) [106].

7 Specifically dissecting CRH/CRH-R1-dependent circuitries in the central nervous system modulating anxiety-related behaviour

The traditional gene targeting approach, knocking out genes by homologous recombination in murine embryonic stem cells, bares several limitations. Many genes have different functions during embryogenesis and adulthood. In a worst-case scenario, targeting of these genes can result in premature embryonic lethality as a consequence of the earliest non-redundant function of the targeted gene and thus would exclude the analysis of its function in adulthood. Furthermore, the knockout of a gene from the earliest stages of development on will activate unpredictable adaptive mechanisms to compensate for the loss of gene function. Hence, the interpretation of the observed phenotypic alterations in the adult mutant might be additionally complicated by another dimension of complexity [107].

Regarding these concerns, conventional CRH-R1 knockout mice display analogous limitations. The behavioural analysis of CRH-R1 knockout mice is hampered due to the fact that these mice show a chronic deficiency in plasma corticosterone [77,78]. As discussed earlier, glucocorticoids are known to influence a variety of emotional and cognitive processes, and are involved in modulating fear and anxiety-related behaviour. Therefore, it remains elusive, whether the anxiolytic effect observed in conventional CRH-R1 knockout mice results either from the CRH-R1 deficiency itself or from pronounced reduction of circulating corticosterone levels.

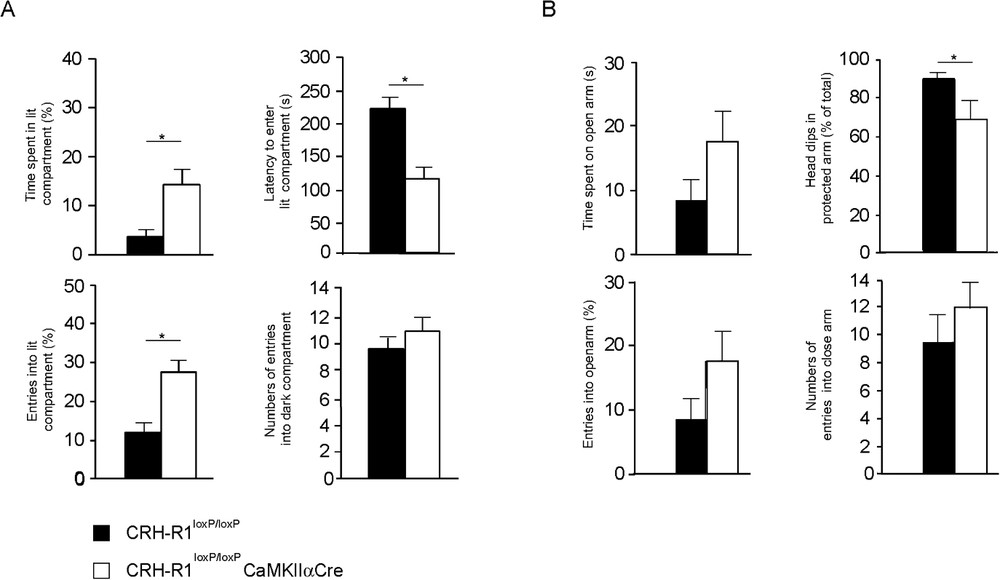

To overcome these limitations, genetic switches have been developed that allow inactivation of genes in a spatially and temporally controllable fashion. In the mouse, this has been accomplished applying binary systems in which gene expression is dependent on the interaction of two components, resulting in either transcriptional transactivation (e.g., Tet-system) or DNA recombination (e.g., Cre/loxP system) [107]. We inactivated the CRH-R1 site-specifically utilizing the Cre/loxP system. Due to the calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase subunit IIα promoter driven Cre (CaMKIIαCre) expression, the CRH-R1 is inactivated postnatally in the anterior forebrain, including limbic brain structures, while sparing hypothalamic and pituitary expression sites intending to leave HPA system regulation undisturbed [108]. The site-specific disruption of CRH/CRHR1 signalling pathways in behaviourally-relevant limbic neuronal circuitries confirmed the significantly reduced anxiety-related behaviour previously observed in conventional CRH-R1 knockout mice [77,78]. The anxiety-reduced phenotype of conditional CRH-R1 mutants was confirmed in two independent behavioural paradigms, the dark-light box and the elevated plus-maze test (Fig. 4) [109]. As anticipated, the conditional disruption of the CRH/CRH-R1 system leaves HPA system regulation functionally undisturbed and, accordingly, plasma ACTH and corticosterone levels were in a normal range in CRH-R1loxP/loxPCaMKIIαCre animals compared to CRH-R1loxP/loxP control mice under basal, stress-free housing conditions. These findings implicated that the behavioural phenotype of conditional CRH-R1 mutants is not influenced by CNS effects of circulating stress hormones. Moreover, conditional CRH-R1 mutants showed normal stress hormone responses to different durations of immobilization stress. However, plasma ACTH and corticosterone responses to stress were prolonged in conditional mutants pointing to an impaired negative feedback regulation of the HPA system. Deficits in stress-induced mineralcorticoid receptor (MR) expression in the hippocampus further support an impaired central negative feedback of the HPA system in CRH-R1loxP/loxPCaMKIIαCre animals. In light of the recently identified impact of CRH on hippocampal MR expression, these results provide additional, genetic evidence for a functional interaction between limbic CRH/CRH-R1 pathways and MR regulation [109,110].

Reduced anxiety-like behaviour in CRH-R1loxP/loxPCaMKIIαCre conditional mutants. (A) Conditional mutants show significantly reduced anxiety-related behaviour in the dark-light box paradigm. Conditional mutants (white) showed a significant increase in percentage of entries into and time spent in the lit compartment, whereas the latency to enter the lit compartment was significantly reduced compared to CRH-R1loxP/loxP control (black) mice. (B) The anxiolytic phenotype of CRH-R1loxP/loxPCaMKIIαCre conditional mutants was confirmed in the elevated plus maze test. Conditional mutants enter the open arms more often and spent more time on the open arm. As a parameter of increased exploratory behaviour, conditional mutants displayed a significant reduction of head-dips in the protected arms as a percentage of total head-dips. However, in both paradigms the general activity of conditional mutants versus control mice was indistinguishable, reflected by the number of entries into the dark compartment and the closed arm, respectively.

Reduced anxiety-like behaviour in CRH-R1loxP/loxPCaMKIIαCre conditional mutants. (A) Conditional mutants show significantly reduced anxiety-related behaviour in the dark-light box paradigm. Conditional mutants (white) showed a significant increase in percentage of entries into and time spent in the lit compartment, ... Lire la suite

In summary, the conditional targeting of CRH-R1 precisely allowed us to dissect genetically CRH/CRH-R1 pathways modulating behaviour from those regulating neuroendocrine function. Thereby, these results support a prominent role for CRH-R1 in limbic neuronal circuitries mediating anxiety-related behaviour independent of HPA system activity and implicate the requirement of limbic CRH-R1 in central negative feedback control of the HPA system [63].

8 Concluding remarks

The development of novel classes of antidepressant and anxiolytic drugs that possess fewer side effects and an acceleration of response by acting more causally than existing therapies is a major future goal in psychiatric research. A growing body of evidence suggests that the neuroendocrine and behavioural phenotypes of depression and anxiety disorders are, at least in part, mediated by modulation of CRH neurocircuitry and that normalization of an altered neurotransmission after treatment may lead to restoration of disease-related disturbances. This concept was originally derived from peripheral HPA system assessments in depressed patients but, with the combination of molecular genetics and behavioural pharmacology, it has been proven that central CRH neuropeptidergic circuits, other than those driving the peripherally accessible HPA system, may be hyperactive and could be therapeutic targets of antagonist action. First clinical data using a CRH-R1-specific antagonist were encouraging, but further research and development will be needed to determine whether pharmacological targeting of the CRH system provides efficacious alternatives to existing antidepressant drug treatments for mood and anxiety disorders [111].

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Max Planck Society, the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) within the framework of the NGN2 and by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.