1 Introduction

Surface treatment (ST) is a very important industrial sector in Europe and in France, Franche-Comté is especially concerned. ST industry supplies a great variety of products for various industrial and domestic sectors including the motor, building, electronic, military and also clothing industries. However, their activities are energy- and water-consuming as well as highly chemically polluting. Indeed, ST is well known to be one of the largest consumers of chemicals (toxic metals known to be harmful to humans and to the environment in particular) and to generate large amounts of toxic waste water with a complex composition [1]. The main pollutants are metal ions such as Cr(III), Cr(VI), Zn, Sn, Cu, Ni, Ag and Fe, organic substances such as chloroform and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and other non-metallic pollutants such as cyanide, boron, and fluoride. Despite the efforts made to clean up their polycontaminated effluents, most commonly by physicochemical treatment [2], industry and scientists are confronted with a great challenge: to remove the entire load of organic and inorganic pollutants to assess their ecotoxicological effects and hence move towards zero pollution discharge [3,4]. While pollutant mixtures present in discharge water after treatment are relatively easy to characterize chemically, assessing their impact on the environment is usually difficult [2]: over the past few decades, ecotoxicological methods have been developed to complete chemical analysis [5].

Bioassays are widely carried out following national and international recommendations. Some very different organisms are commonly used in ecotoxicological bio-monitoring: primary producers (algae, i.e. Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata [6]), primary consumers (aquatic invertebrates, i.e. Daphnia magna, Gammarus pulex [7]) or secondary consumers (aquatic vertebrates, i.e. Gambusia holbrooki [8]). Less frequently used in comparison with faunal tests [9], toxicity studies using higher plants have however increased in recent years [11,12]. Ratsch and Johndro [13] first concluded that the inhibition of root elongation (RE) is a valid and sensitive indicator of environmental toxicity. Several articles [10,14–20] have since shown that phytotoxicity tests like seed germination rate (GR) and RE tests present many advantages as summarized in Table 1. These bioassays are simple, inexpensive and only require a relatively small amount of sample. Moreover, the seeds remain usable for a long time. The most common plant species recommended by, among others, the US Environmental Protection Agency [21], the US Food and Drug Administration [22], and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [23] are cucumber Cucumis sativus, lettuce Lactuca sativa L., radish Raphanus spp L., red clover Trifolium pratense L., and wheat Triticum aestivum. Previous studies [20,24] compared some of these species and recommended L. sativa as a bioindicator to determine the toxicity of soil and water samples.

Major advantages of phytotoxicity assays using vascular plant seeds.

| Advantages of phytotoxicity tests involving seeds (seed germination rate, root elongation, etc.)a |

| Simple and very reproducible method |

| Applicable in situ and in vitro |

| No requirement for major equipment |

| Minimal maintenance costs |

| Seeds are self-sufficient (no adjuvants/nutrients needed in the test water) |

| Only small sample size required (e.g. water, effluent, soil, sediment) |

| No seasonality |

| Seeds can be easily purchased in bulk |

| Seeds remain viable a long time |

| Rapid germination |

a Based on multiple references including [10,14,15,17].

Haugland and Brandsaeter [25] previously studied the effects of various procedures and conditions on bioassay sensitivity in allelopathic studies. They pointed out that the lack of real standardized bioassays makes comparison between studies very difficult. It is nowadays in fact the proceedings that are not standardized: even when phytotoxicological bioassays using lettuce are performed in accordance with national or international standards, multiple parameters remain variable (Table 2). Di Salvatore [10], studying synthetic solutions containing metal ions, found that lettuce GR and RE were not affected by substrate, agar agar vs. filter paper. However, there is no literature comparing the parameters used of industrial effluent, as that of the ST industry.

Non-exhaustive list of parameters that remain variable in seed germination bioassaysa.

| Parameter | Examples |

| Cultivar | Regina; Buttercrunch; Trocadero; Divina; Iceberg; non-specified |

| Support | Agar agar; filter paper; germination paper; non-specified |

| Seed pre-treatment | Yes; no; non-specified–When yes: 10 or 30% hypochlorite solution |

| Temperature [in °C] | 20; 24; 28; room temperature; non-specified |

| pH | 5.5 to 8.2; non-specified |

| Dish | Glass; polyethylene; non-specified |

| Number of seeds | 10; 20; 50; non-specified |

| Amount of sample | 4 mL; 9 mL; non-specified |

| Duration | 72 to 192 h |

| Control water | Distilled; deionized; milliQ; non-specified |

The present study is based on the assessment that proceeding parameters could affect the ecotoxicity diagnosis. Indeed, we tested three of the most variable parameters, using GR, root and total lengths as end points: control water quality, number of seeds per germination dish and lettuce cultivar.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Industrial discharge waters

During this study, discharge waters were once collected in three different surface treatment companies (denoted Co1, Co2 and Co3) in the Franche-Comté region. Effluent samples were collected at the outlet of the decontamination station of each company. The main activities of each company and the related major environmental concerns are reported in Table 3. The table also shows the concentration threshold in discharge for key pollutants. Table 4 shows the characteristics of the samples studied here, taken from three different surface treatment companies (Co1S1, Co2S1 and Co3S1). The effluents are average samples, characteristic of daily activity. Each treated water sample was tested following the same concentration range: 25, 50, 75 and 100%. All dilutions were prepared in Reverse Osmosis Water (ROW).

Main environmental issues encountered by the two surface treatment companies and the regulatory values (in mg·L−1) for different pollutants contained in the water discharges (French law of 5th September 2006).

| Company and main activity | Contaminant(s) of major concern | Threshold emission value (mg·L−1) |

| Co 1 | Zn | 3.5 |

| Treatment by electrolysis | Ni | 3.5 |

| Co2 | Fe | 5 |

| Plating with precious metals | Ni | 2 |

| Co3 Surface treatment of aluminum |

Al | 5 |

Physicochemical characteristics of three discharge waters (Co1S1, Co2S1, Co3S1) from the three industrial sites investigated in this study.

| Parameter/Metal | Co1S1 | Co2S1 | Co3S1 |

| pH | 8.5 | 8.4 | 6.9 |

| Conductivity | – | 1730 | 3280 |

| Fe | 1.97 | 5.18 | 0.117 |

| Cr | 0.13 | 0.079 | 0.12 |

| Zn | 2.67 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| Ni | 0.6 | 0.96 | 0.49 |

2.2 Lettuce seeds

Four lettuce (L. sativa L.) cultivars were germinated: Appia (A), batavia dorée de printemps (B), grosse blonde paresseuse (GBP) and Kinemontepas (K). They were chosen among the 1500 or so commercially available cultivars. The seeds (Caillard, Avignon, France) were all kept under laboratory conditions, in the dark and shielded from large modifications of temperature and moisture [1].

2.3 Control and toxicity test

Germination rates for samples were evaluated using the French normalized method ISO 17126 [31]. Tests were conducted using 100 × 15 mm disposable plastic Petri dishes and two layers of filter paper. Thirty plump undamaged seeds of almost identical size were laid on the filter paper in each dish, which contained 4 mL of industrial discharge water (pH ∼ 8.4). Each condition was tested in triplicate. All dishes were kept in the dark, at 24 ± 1 °C, for seven days of exposure. As recommended by the normalized method [31], a control test with distilled water was performed in triplicate for every condition tested. Multiple parameters were tested as described in Table 5. After seven days, germinated seeds were counted (GR) using equation (1) (where GSS is the number of Germinated Seeds in the Sample and GSC the number of Germinated Seeds in the Control) and plantlet growth measured (root and total lengths; RL and TL; the total length refers to the root and hypocotyl of the plantlets).

| (1) |

Parameters assessed here.

| Quality of water | Distilled water DW (pH 7.3) |

| Mineral water Evian®, E (pH 7.2) | |

| Reverse osmosis water ROW (pH 6) | |

| Ultra pure water UPW (6.05) | |

| Number of seeds per Petri dish | 15 |

| 20 | |

| 30 | |

| Cultivar of lettuce | var. Appia (A) |

| Lactuca sativa | var. batavia dorée de printemps (B) |

| var. grosse blonde paresseuse (GBP) | |

| var. Kinemontepas (K) |

As recommended by the normalized method [31], GR under 90% is unacceptable for control conditions. Control water pH did not skew germination test results as long as it remained between 5.5 and 9.5.

2.4 Statistical analysis

All homoscedasticities were tested using a Bartlett test as prerequisite for parametric test. The GRs were compared using the Chi2 test and lengths (root and total) using Kruskal–Wallis tests, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with R (2.15.1) (R Development Core Team, 2013, www.r-project.org).

Dose-dependent curves and EC50 values were calculated with Hill's model using the macro Excel Regtox free version EV 7.0.6.

Germination Index (GI) [32–35] were used to assess the response variability between lettuce cultivars. Calculations of these indexes were performed using the equations (2) where RLS is the Root Length of the Sample, RLC the Root Length of the Control.

| (2) |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Control water

Four kinds of water (distilled, mineral, reverse osmosis, and ultra pure) were used as controls. Table 6 reports the relative data of GR and RL of seeds watered with the different control waters. The assay was performed on the same cultivar of lettuce L. sativa. The results showed that neither GR nor root length showed significant differences. For practical reasons, the control water chosen was ROW.

Comparison between germination rate (GR) and root length RL means (± SD; n = 3) of L. sativa var Batavia dorée de printemps (B) watered with four different control waters (E, UPW, ROW, DW).

| E | UPW | ROW | DW | P value | |

| GR (%) | 100 | 99 ± 1.6 | 98 ± 3.1 | 94 ± 1.6 | 0.067 |

| RL (mm) | 14.28 ± 4.47 | 14.64 ± 5.99 | 17.80 ± 9.11 | 14.44 ± 5.79 | 0.147 |

| TL (mm) | 63.14 ± 4.20 | 61.33 ± 6.26 | 65.21 ± 6.18 | 67.73 ± 1.16 | 0.441 |

We synchronically tested the potential ecotoxicological differences between the four cultivars watered with ROW. Results (Table 7) showed no statistical GR or RL differences between the different cultivars. Total lengths appeared to be different, especially Appia's total length from the three others. Differential cultivar total length was attributed intrinsic natural differences as far as root lengths were not significantly different.

Comparison between germination rate GR and root length RL means (± SD; n = 3) of 4 lettuce cultivars watered with ROW.

| A | B | K | GBP | P value | |

| GR (%) | 95 ± 4.1 | 96 ± 2.9 | 93 ± 3.9 | 96 ± 3.4 | 0.357 |

| RL (mm) | 16.20 ± 5.40 | 25.70 ± 9.49 | 28.07 ± 8.16 | 24.49 ± 9.91 | 0.08 |

| TL (mm) | 57.49 ± 10.56 | 71.50 ± 14.55 | 81.05 ± 12.86 | 74.27 ± 15.02 | 0.02 |

3.2 Number of seeds per dish

Three seed densities (15, 20 and 30 seeds per dish; ROW) were tested, using the same lettuce cultivar (var. B). The results for the three bioassay endpoints are detailed in Table 8. It can be seen that there was no significant difference between GR (100%; 95%; 98%) and both root (17.5; 18.5; 17.8 mm) and total (62; 71; 65.4 mm) length of the plantlet grown in dishes containing 15, 20, and 30 seeds, respectively.

Number of seeds per Petri dish versus germination rate GR (%), root and total lengths RL and TL (mm) of L. sativa var B (ROW; n = 3 replicates).

| Number of seeds | GR (%) | RL (mm) | TL (mm) | P value |

| 15 | 100 | 17.5 ± 8.5 | 62 ± 12.7 | |

| 20 | 95 ± 4 | 18.5 ± 5.75 | 71 ± 8.75 | > 0.05 |

| 30 | 98 ± 3 | 17.8 ± 9.1 | 65.4 ± 16.8 |

Weidenhamer et al. [36] reported that the number of seeds relative to the solution volume used in a seed germination bioassay was a factor in the results obtained as the amount of ferulic acid available to each seed influenced germination, rather than chemical concentration of the tested solution. It seems that there is not such a consensus about the effect of seed number on length: some report a correlation (e.g., [37]) and some do not (e.g., [38]). Our results show that for a 4 mL sample, the number of seeds (15 to 30 seeds) did not affect either germination or elongation. For practical reasons, the number of seeds per dish was fixed at 20.

3.3 Seed cultivar

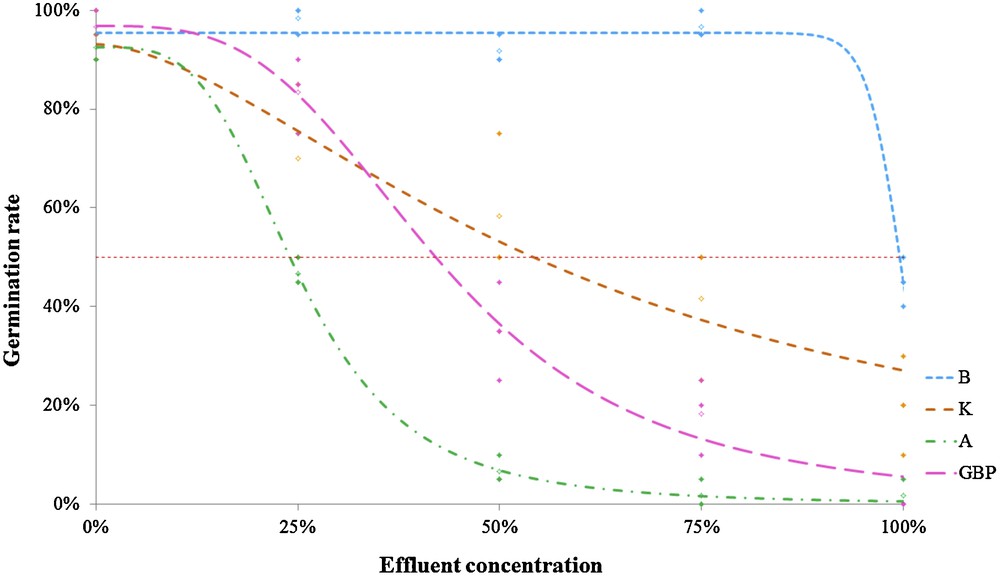

Bioassays were conducted using a sample of raw discharge water, taken from three different surface treatment companies (Co1S1, Co2S1 and Co3S1). The characteristics of the samples are reported in Table 4. Fig. 1 shows the four different dose–response curves of the four lettuce cultivars watered with Co1S1. It can be seen that when watered with the same effluent sample, the four cultivars did not show the same ecotoxicological response. This was confirmed by the results described in Table 9, which presents the GR and GI values for every diluted sample assessed on the four lettuce cultivars, and the EC50 values for every sample. GR decreased with all the four raw samples. The intensity of the decrease depends on the sample (e.g., var B's GR varied from 45 ± 4.1 to 93 ± 2.4%). Indeed, Charles et al. [1] showed that lettuce ecotoxicological response variability can be linked with the chemical composition of the samples, which varies on a daily basis (Table 4). Differences between GRs were significant: for example, values for undiluted Co1S1 were 2 ± 2.4%, 45 ± 4.1%, 0% and 20 ± 8.2% for var A, var B, var GBP and var K, respectively (Fig. 1). The same observation was made considering all the tested samples and EC50s (Table 4). After comparing GR and EC50 values, var A was found to be the most sensitive cultivar, vars K and GBP medium, and var B the most resistant to the three effluents tested. This was confirmed by comparing the GR/EC50 sensitive scale with the GIs sensitive scale.

Lettuce germination rate versus concentration of Co1S1 raw discharge waters for the four lettuce varieties (batavia B, Kinemontepas K, Appia A and grosse blonde parresseuse GBP).

Germination rate, EC50 and germination index values for the four lettuce cultivars watered with the four effluent samples.

| Sample | Lettuce cultivar | Treatment (tested effluent concentration) | ||||||

| 25% | 50% | 75% | 100% | EC50 | Sensitivity Scale | |||

| Germination rate | Co1S1 | B | 98 ± 2.4 | 92 ± 2.4 | 97 ± 2.4 | 45 ± 4.1 | 99.75 | B > K > GBP > A |

| GR [%] | K | 70 ± 14.7 | 58 ± 11.8 | 42 ± 11.8 | 20 ± 8.2 | 59.15 | ||

| A | 47 ± 2.4 | 7 ± 2.4 | 2 ± 2.4 | 2 ± 2.4 | 25.11 | |||

| GBP | 83 ± 6.2 | 35 ± 8.2 | 18 ± 6.2 | 0 | 42.93 | |||

| Co2S1 | B | 73 ± 2.4 | 93 ± 2.4 | 87 ± 6.2 | 77 ± 14.3 | n.a. | B∼K∼GBP > A | |

| K | 95 | 92 ± 5 | 92 ± 2.5 | 87 ± 2.5 | n.a. | |||

| A | 82 ± 8.5 | 52 ± 14.3 | 33 ± 6.2 | 28 ± 14.3 | 61.17 | |||

| GBP | 97 ± 4.7 | 97 ± 6.2 | 97 ± 4.7 | 68 ± 6.2 | n.a. | |||

| Co3S1 | B | 98 ± 2.4 | 90 ± 4.1 | 88 ± 2.4 | 85 ± 4.1 | n.a | B∼K > GBP > A | |

| K | 97 ± 4.7 | 100 | 98 ± 2.4 | 92 ± 2.4 | n.a | |||

| A | 93 ± 2.4 | 82 ± 6.2 | 67 ± 6.2 | 35 ± 4.1 | 90.01 | |||

| GBP | 100 | 98 ± 2.4 | 88 ± 2.4 | 72 ± 4.7 | n.a | |||

| Germination index | Co1S1 | B | 1.5 | 1.45 | 1.42 | 0.4 | B > >K > GBP > A | |

| GI | K | 0.96 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.13 | |||

| A | 1.12 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||||

| GBP | 0.89 | 0.51 | 0.23 | 0 | ||||

| Co2S1 | B | 1.21 | 1.16 | 1.42 | 1.18 | B > GBP∼K >A | ||

| K | 0.73 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.98 | ||||

| A | 1.23 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.32 | ||||

| GBP | 1.21 | 1.16 | 1.13 | 0.85 | ||||

| Co3S1 | B | 1.01 | 0.77 | 0.7 | 0.53 | B∼GBP > K > >A | ||

| K | 1.04 | 0.88 | 0.7 | 0.56 | ||||

| A | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.23 | ||||

| GBP | 1.32 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.49 |

Although GR (lethal endpoint) is the most commonly used endpoint, it is not the most sensitive [39]: root length (sublethal endpoint) has often proved to be a more sensitive parameter, but not as easy to measure as germination. This is the reason why GI, first defined to assess compost toxicity [32], combines advantageously relative seed germination and RE measurements, generating an objective sensitivity scale, here: B > K > GBP > A, where the Appia cultivar is the most sensitive of the four.

Toxicity and ecotoxicity depend on the bioassay indicator and the endpoints considered [40]. Differences in sensitivity of plant species to various pollutants have been demonstrated [10,41–43]. Wang and Freekmark [17] reviewed and concluded that sensitivity varies among toxicants and taxonomic groups and species. The choice of the bioindicator variety has already been showed for species like potato or wheat. Beside the risk of toxicity underestimation when only one bioassay is used [44], Cairns and Pratt [45] concluded that the potential difference in results from one species to another may affect the extrapolation accuracy.

4 Conclusion

This study demonstrated that among multiple variable germination and elongation test proceeding parameters, control water quality and seeds density did not affect neither lettuce GR nor root or total lengths. However, when sensitivity differences among species are well known, it appears that the cultivar has a major effect in the assessment of discharge water toxicity: we suggest choosing carefully the bioindicator cultivar, and maybe carrying out rapid tests among multiple cultivar. It would be interesting in further investigations to determine which physiological phenomena (e.g., metal uptake) are different, and can explain the ecotoxicological differences observed.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Ville de Besançon, which funded Anne Priac's PhD, to Sophie Gavoille and Céline Lagarrigue from the “Agence de l’eau Rhône Méditerrannée Corse”, and to the FEDER (“Fonds européens de développement regional”) for financial support (NIRHOFEX Program 2013–2017). Michael Coeurdassier and Peter Winterton are thanked for critical discussions, and Coline Druart, Philippe Antoine, Xavier Hutinet, and Jocelyn Paillet for technical assistance.