The Global Positioning System (GPS) is a new and powerful tool for understanding the present-day crustal deformations. Such studies were successfully carried out in some famous seismic areas, such as Japan, California, Turkey and Greece. A new exceptional contribution on GPS in China has just been published in Science [7]. It concerns a territory of ten million square kilometres, including Himalayas, part of Tibet and southern China. The GPS data show a very peculiar displacement field, due to the penetration of India into Asia, and reflect the present-day intracontinental deformation of Asia. I would like to show here that there is a simple relationship between the present velocity field and the geological deformation at a scale of 1000 km.

Fig. 2 shows that India is bounded to the north by the Himalayan Mountains, which are the result of its northward continental subduction beneath Asia since more than 30 Myr BP [6,8]. India is bounded to the west and to the east by two major strike-slip faults, associated with intense folding, the sinistral Chaman Fault and the dextral Sagaing Fault, both with horizontal displacement of at least 1000 km. These structures are combined to form the western (Nanga Parbat) and eastern (Burma) Himalayan virgations.

Structural scheme of the East-Himalayan virgation, showing the progressive clockwise rotation related to the northward displacement of India, from 53 Myr BP to now. H43, H33, H20, H0 show the successive position of the frontal Himalayan thrust (in Myr).

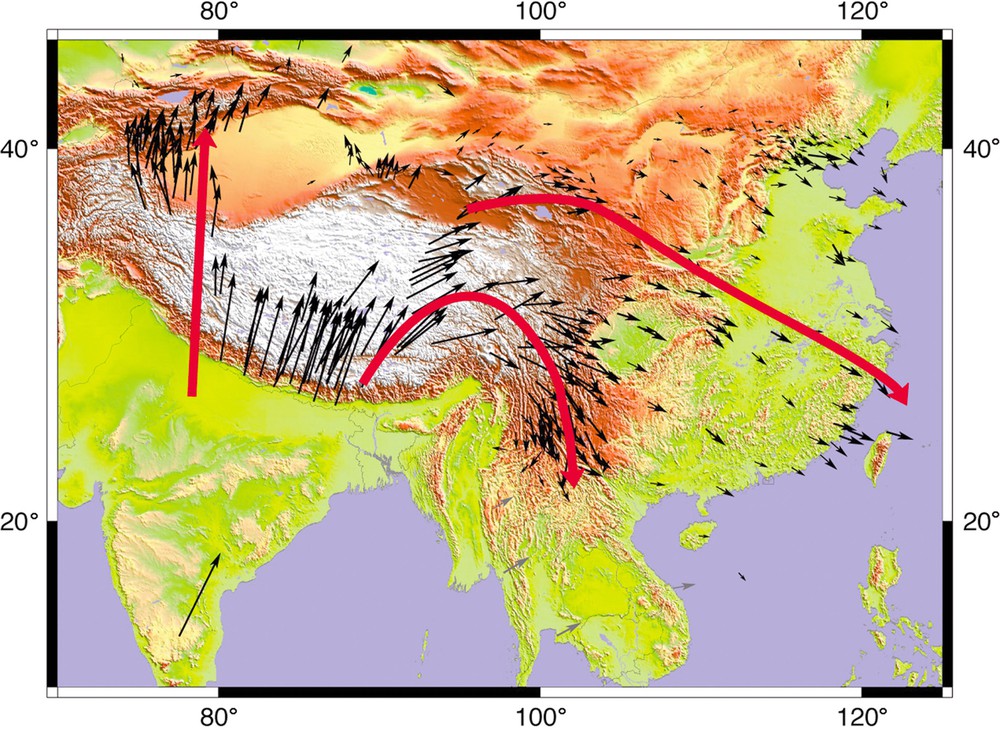

The map (Fig. 1) shows the GPS velocity vectors with respect to the stable Eurasia [3,7,9,10]. Three areas can be defined.

Present-day crustal deformation in China constrained by Global Positioning System (GPS) measurements. Modified from [1], with additional GPS data from Sundaland (personal communication of C. Vigny).

1. In the western part, from the frontal part of the Himalayas up to the TienShan intracontinental mountain range, the vectors are roughly north–south [1]. These vectors clearly reflect the present-day northward displacement of India, which continues since 40 Myr with the same direction.

2. In the middle part, the vectors show a curved pattern with a 150° rotation, from N20° with a northward motion, through east–west with an eastward motion, to north–south with a southward motion. These trajectories are arranged as circle arcs, with an average radius of 500 km over an area 200–300 km broad.

This simple instantaneous deformation field at a great scale (one million square kilometres) reflects a long geological history (roughly 30 Myr), corresponding to a large clockwise rotation. In the Burma virgation, the main ophiolitic suture and the South-Tibetan Lhasa block rotated of more than 90° over a length of 1000 km.

I propose that the displacements evidenced by GPS are the last present-day increments of a continuous deformation during more than 30 Myr, resulting from the northward continental subduction and penetration of India into Asia after the collision of these two continents. In the frontal part of India, the displacement field is simple, as was the deformation field since 30 Myr BP, with a constant north–south direction. On the eastern border, around the Burma virgation, the dextral strike-slip motion of India relatively to Asia was accompanied by a large continuous clockwise rotation since 30 Myr, as it is well evidenced by palaeomagnetic data [2,4], still active today, as shown by GPS measurements.

3. In the eastern part, the vectors are roughly east-southeast–west-northwest and indicate an eastward moderate displacement of the China block. Clearly, we deal here with a different mechanism, with a larger scale. I have proposed that it might correspond to a lateral expulsion of the asthenosphere beneath the Tibet [5].

In conclusion, the instantaneous rotational deformation evidenced by GPS is the final result of a long (30 Myr) rotational deformation history in relation to a large (1000 km) strike-slip intracontinental deformation, during the progressive penetration of India into Asia. GPS and geology are thus complementary tools for mountain-building understanding.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Stéphane Dominguez and Philippe Matte for discussions, Pei-Zhen Zhang for fruitful contact, Philippe Vernant for technical support, Christophe Vigny for personal communications, and Anne Delplanque for drafting.