Version abrégée

1 Introduction

Une des caractéristiques principales de la chaı̂ne himalayenne est la coexistence d'une tectonique extensive et d'une tectonique compressive, comme on l'observe dans la partie supérieure et dans la partie inférieure du cristallin du haut Himalaya (CHH). Un système de failles normales de bas angle (South Tibetan Detachment System, STDS) a été reconnu dans la partie supérieure du CHH, tant au Népal oriental qu'au Tibet méridional [2,3,5]. Ceci a conduit à formuler des modèles d'extrusion de noyaux métamorphiques, avec des implications importantes pour l'évolution tectono-métamorphique des chaı̂nes orogéniques [7,10,18,27,33]. Cependant, à l'ouest de la chaı̂ne de l'Annapurna, le STDS est beaucoup moins évident [1,32]. Au Népal occidental, ce contact a été interprété comme transitionnel [12,13] ; le prolongement vers l'ouest du STDS restait donc incertain. L'objectif de ce travail est l'analyse structurale d'une section au Népal occidental (Fig. 1) en vue de la recherche de ce contact entre le CHH et le SST.

Geological sketch map of the Nepal Himalayas with location of the study area.

Carte géologique schématique de l'Himalaya du Népal et localisation de la région étudiée.

2 Cadre géologique

Du sud au nord, l'Himalaya népalais et le Tibet méridional sont caractérisés par la division tectono-géomorphologique suivante :

- – les Siwalik Hills, constitués par des dépôts d'avant-pays, d'âge compris entre le Miocène et le Plio-Pléistocène ;

- – le bas Himalaya, délimité au sud par le Main Boundary Thrust (MBT) et au nord par la zone du Main Central Thrust (MCT) et constitué par des sédiments (Précambrien–Éocène) très peu métamorphiques et, au-dessus, par les « nappes cristallines du bas Himalaya », caractérisées par des roches plus métamorphiques ;

- – le haut Himalaya, représenté par des nappes de charriage de roches métamorphiques (CHH), sous la Zone tibétaine, formée de roches sédimentaires ; le contact entre les deux ensembles est caractérisé par la présence de plutons de leucogranites miocènes ;

- – le Plateau tibétain, constitué par des sédiments marins de la Téthys, déformés et déposés sur la marge indienne, d'un âge compris entre le Cambrien (?)–Ordovicien inférieur et l'Éocène [12,15].

3 Cristallin du haut Himalaya

La partie inférieure (formation 1 [24]), constituée par des paragneiss et des micaschistes à disthène, est fortement déformée. La paragenèse métamorphique est constituée par Qtz+Pl+Bt+Ms±Grt±Ky±St±Sil+tourmaline, rutile, zircon, apatite et oxydes de fer et titane comme accessoires (symboles après Kretz [23]). Le disthène et la sillimanite sont déstabilisés et entourés aussi bien par la muscovite que par la biotite, alors que la staurolite se trouve, parfois, incluse dans des porphyroblastes de grenat. Dans la partie haute de la formation 1 sont présents des gneiss à sillimanite : la sillimanite, uniformément orientée le long de la foliation principale, est bordée aussi bien par la muscovite que par la biotite, témoignant donc d'une étape rétrograde en faciès des schistes verts (Fig. 2). La formation 2 [24] est constituée par des marbres, des gneiss calcsilicatés et par des roches psammitiques, subordonnées. La formation 3 [24] est représentée par des orthogneiss et des gneiss migmatitiques, souvent parcourus par des filons leucogranitiques à tourmaline.

Microphotograph of sillimanite-bearing gneisses of the HHC (Formation 1, Gorphung Khola section) showing sillimanite crystals elongated parallel to the S2 foliation surrounding microlithons constituted of Ky armoured with Ms (scale bar: 1.2 mm).

Microphotographie de gneiss à sillimanite de l'HHC (formation 1, section Gorphung Khola), montrant des cristaux de sillimanite allongés parallèlement à la foliation principale, qui entoure des microlithons, constitués de disthène armé par de la muscovite (échelle : 1,2 mm).

Dans cette note, nous avons reconnu que la partie supérieure du cristallin du haut Himalaya était constituée par des marbres et des roches calcsilicatées avec un métamorphisme de faciès amphibolite. Les roches calcsilicatées sont caractérisées par l'association stable Qtz+Pl+Kfs+Cpx+Ep+Scp+Grt+Bt+Ms±Cc±Pl±Hbl (minéraux accessoires : titanite, tourmaline, apatite, rutile, zircon et oxydes de fer et de titane) et sont souvent intercalées dans les gneiss. Les marbres sont caractérisés par l'association Cc+Cpx+Bt±Pl±Scp (minéraux accessoires : titanite, tourmaline, apatite, rutile, zircon et oxydes de fer et titane).

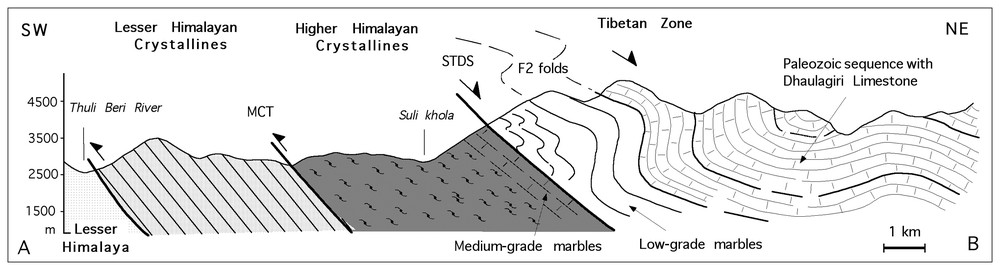

La fabrique principale est représentée par une foliation mylonitique (S2), orientée NW–SE, avec des pendages vers le nord-est compris entre 30 et 60° (Fig. 3) et marquée par l'orientation préférentielle de Qtz, Bt, Ms et Ky. Les indicateurs cinématiques indiquent un sens de mouvement vers le sud-ouest.

Geological sketch map of the Dolpo area (from Fuchs [11] and authors' personal work). 1: Lower Himalayas; 2: Lower Himalayas Crystalline (LHC); 3: Higher Himalayan Crystalline; Tibetan Zone: 4: low-grade crystalline marbles; 5: Palaeozoic sequence, including Dhaulagiri Limestone; 6: Triassic–Jurassic sediments; 7: main foliation (S2 in the LH, LHC and HHC and S1 in TZ); 8: vertical foliation; 9: horizontal foliation; 10: S2 foliation in the TZ; 11: F2 fold axes; 12: horizontal F2 fold axes and their vergence; 13: L2 stretching lineation; 14: main normal faults; 15: main thrusts (MCT: Main Central Thrust); 16: detachment (STDS: South Tibetan Detachment System); 17: trace of the geological cross-section A–B in Fig. 5.

Carte géologique (par Fuchs [11] et relevé original des auteurs) de la région du Dolpo. 1 : Bas Himalaya ; 2 : nappe cristalline du bas Himalaya (LHC) ; 3 : cristallin du haut Himalaya ; série sédimentaire tibétaine : 4 : marbre peu métamorphique ; 5 : séquence paléozoı̈que, y compris les calcaires du Dhalaugiri ; 6 : sédiments triasico-jurassiques ; 7 : foliation principale (S2 dans le LH, LHC et HHC, et S1 dans le TZ) ; 8 : foliation verticale ; 9 : foliation horizontale ; 10 : foliation S2 dans le TZ ; 11 : axes des plis 2 ; 12 : axes des plis 2 horizontaux, sens de vergence ; 13 : linéations d'allongement ; 14 : failles normales principales ; 15 : chevauchements principaux ; MCT : Main Central Thrust ; 16 : détachement ; STDS : South Tibetan Detachment System ; 17 : localisation de la coupe géologique (A–B) in Fig. 5.

4 Série sédimentaires tibétaines

La partie inférieure de la série sédimentaire tibétaine est constituée par des calcaires impurs, des calcschistes et quartzites de la formation du Dhaulagiri [12]. Elle est caractérisée par l'association métamorphique Cal+Qtz+Ms+Bt±Chl±Scp. Dans la partie inférieure de la série sédimentaire tibétaine (SST) ont été reconnues trois phases de déformation. La première phase (D1), la plus pénétrative, est associée au développement d'une foliation S1, continue dans les niveaux plus pélitiques et plus espacée dans les niveaux plus compétents, développée parallèlement aux plans axiaux des plis F1. La phase D2 est associée au développement d'une foliation S2, qui varie entre une foliation pénétrative à un clivage de crénulation, plan axial d'un plissement asymétrique indiquant une vergence vers le nord-est (Figs. 4 et 5).

Northeast-verging F2 folds in the marbles of the TZ south of Kangmara Pass (scale bar: 10 cm).

Plissements F2 asymétriques dans les marbres cristallins impurs de la SST au sud du Kangmara La (échelle : 10 cm).

Schematic geological cross-section (A–B) through the main tectonic units of the study area. The trace is indicated in Fig. 3.

Coupe géologique (A–B) dans la zone étudiée. Pour la localisation, voir la Fig. 3.

Pendant la phase D3 se développent des plis ouverts avec des plans axiaux très raides, associés à un clivage de crénulation S3. La partie inférieure de la SST est recoupée par des dykes leucogranitiques à tourmaline, déformés par la phase D2 (Fig. 6).

Rotated leucogranite dike with a shape similar to a δ object in the marbles of the lower part of the TZ; Gorphung Khola. The dike has been rotated toward the northeast during non-coaxial deformation (lens cap 5.2 cm for scale).

Filon leucogranitique renversé vers le nord-est (δ type) dans les marbres cristallins de la portion inférieure de la SST, vallée du Gorphung Khola (pour l'échelle, le couvercle de l'objectif photographique est de 5,2 cm).

Dans la partie inférieure de la SST, proche du contact avec le cristallin du haut Himalaya sous-jacent, on observe une augmentation du degré métamorphique [1,15,32], accompagnée d'une augmentation de la déformation et d'une variation des mécanismes de déformation, qui passent d'un mécanisme de basse température (pressure solution) à un mécanisme de haute température (plasticité intracristalline).

5 Le détachement

La partie supérieure du CHH et la partie inférieure de la SST sont constituées l'une et l'autre par des marbres, qui, même s'ils ont eu une évolution métamorphique très différente, ne sont pas faciles à distinguer sur le terrain. En effet, si les marbres de la SST sont caractérisés par un métamorphisme sous faciès de schistes verts (zone à biotite), ceux qui appartiennent au CHH ont un métamorphisme de faciès amphibolite rétromorphosé en faciès de schistes verts.

Dans la portion de la SST immédiatement au-dessus du CHH ont été observés des plis F2, métriques à kilométriques, à vergence vers le nord-est (Figs. 4 et 5). Ces plis sont bien développés dans les premiers 3 à 5 km du SST et indiquent un back-sliding vers le nord-est (Fig. 5). Ils sont analogues à ceux qui ont été reconnus par d'autres auteurs dans d'autres portions de la SST [1,3,5,6,8,22,32].

Des indicateurs cinématiques, représentés par des plis asymétriques, bandes de cisaillement et boudinage et des rotations de filons leucogranitiques, indiquent un sens de transport tectonique haut vers le nord-est (Fig. 6). Ces éléments permettent d'interpréter, dans la région étudiée, le contact entre la SST et le CHH comme un contact extensif présentant des caractéristiques analogues à celles du STDS, mais montrant une déformation plus diffuse.

Les « marbres cristallins » de Fuchs, précédemment attribués en totalité au CHH [11], ont été attribués à deux unités tectoniques différentes : la partie inférieure, caractérisée par un métamorphisme de faciès amphibolite, a été replacée dans le CHH, tandis que la partie supérieure, caractérisée par un métamorphisme de faciès schistes verts, a été attribuée à la SST. Tant par sa position structurale que par ses caractéristiques métamorphiques, la partie inférieure des marbres est comparable à la formation de Larjung [8], qui affleure dans le Kali Gandaki, liée au CHH [32]. En outre, la partie supérieure des marbres a la même position géométrique, le même degré métamorphique, les mêmes caractéristiques lithologiques et structurales que la formation du col nord de l'Everest [35], affleurant dans la zone de l'Everest qui surmonte structuralement le STDS [6,28].

6 Conclusions

Nos conclusions principales sont les suivantes :

- (a) alors que le CHH a une structure monoclinale, le SST immédiatement au-dessus est caractérisé par des plissements asymétriques kilométriques à regard nord-est ;

- (b) dans ce secteur de la chaı̂ne, le CHH est d'épaisseur très réduite (2–5 km), par rapport à d'autres sections du Népal central et centre-oriental ;

- (c) les marbres qui affleurent dans la partie basale de la SST et les marbres de la partie supérieure du CHH ont subi une évolution tectonique et métamorphique différente ;

- (d) dans la SST, la déformation augmente vers le bas, en se rapprochant du contact avec le CHH ;

- (e) la SST est caractérisée par des plis asymétriques à vergence nord-est, développés dans des conditions de faible température.

Toutes ces caractéristiques ont permis de cartographier, dans le bas Dolpo, le contact entre le CHH et le SST, qui est une zone de cisaillement extensive, en corrélation avec le STDS.

1 Introduction

One of the most striking geological features of the Himalayan range is the presence of extensional tectonics on top of the Higher Himalayan Crystalline (HHC), contemporaneous with the shortening along the Main Central Thrust (MCT) at its base [2,21]. A system of low-angle normal faults (South Tibetan Detachment System: STDS) has been detected at the top of the HHC in Nepal and southern Tibet [2,3,5]. This led to the development of models of extrusion of the metamorphic core with consequences on the tectonic and metamorphic evolution of the belt, which helped to clarify the evolution of other ancient and recent mountain belts [7,10,18,27,33].

The STDS has been traced for at least 700 km along the Himalayan chain [2,20], separating the Tibetan Zone (TZ) from the HHC [21]. It is well recognisable in eastern Nepal, where it brings into contact unmetamorphosed Palaeozoic rocks of the TZ with sillimanite-bearing gneisses, up to central Nepal [2]. However, in the Kali Gandaki (West of the Annapurna range), it becomes less evident and uncertainties arise in its location [1,32], due to the downward increase of metamorphism from the TZ to the HHC. A gradual transition from the lowermost TZ to the HHC is reported in northwestern Himalayas [30,34]. In western Nepal, the same contact is reported to be transitional by Fuchs [12], Fuchs and Frank [13]. Therefore, the westward prolongation of the STDS remains uncertain, though it is also crucial in the application of the current geological models and in the understanding of the tectonic evolution of the belt. In addition, very few geological investigations have been performed in this area after the great geological explorations of Fuchs in the 1960s.

The aim of this work is to show structural features along two transects in western Nepal (from Jumla to Chaurikot up to Phoksundo Tal and from Ringmo to Dunai; Fig. 1) to investigate the contact between HHC and TZ.

2 Geological setting

A simple tectonic-geomorphologic zonation characterises the Nepal Himalayas and Southern Tibet [14,25,31, and references therein]. Going from the southern more external areas of the belt towards the high peaks to the north, we have (Fig. 1):

- – the Siwalik Hills, bordering the Ganges plain, made up of Himalayan foreland basin sediments, of Miocene to Pliocene-Pleistocene age;

- – Lower Himalayas, comprising the Mahabharat Range and the Midland zone, are bounded to the south by the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT) and to the north by the Main Central Thrust (MCT). The Lower Himalayas consist of a thick sequence of weakly metamorphosed sediments (Precambrian up to Eocene) and higher-grade metamorphic rocks (Lower Himalayan Crystalline Nappes), which overlie the low-grade metasediments;

- – Higher Himalayas, north of the Lower Himalayan zone, are constituted by thrust sheets of metamorphic rocks that dip gently to the north, the HHC and the overlying TZ; Miocene leucogranite plutons occur at the boundary between the metamorphic and sedimentary sequences;

- – further north, between the main peaks and the Indus Tsangpo suture zone, the mountain ranges of the Tibetan plateau consist of folded Tethyan marine sediments deposited on the north Indian continental margin; the southern Tethyan sediments are a fossiliferous sequence of (?)Cambrian–Early Ordovician to Eocene age [12,15].

High-level plutons of biotite–muscovite granites, the North Himalayan granites, were emplaced mostly during the Miocene in the overlying Tethyan sediments [9].

3 Higher Himalayan Crystalline

The lowest part (Formation 1 [24]) is composed of kyanite-bearing paragneisses and micaschists. Centimetre-size kyanite crystals are frequently found. Formation 1 is strongly deformed and mylonitised.

The metamorphic assemblage is represented by Qtz+Pl+Bt+Ms±Grt±Ky±St±Sil with accessory tourmaline, rutile, zircon, apatite, and FeTi oxides (symbols after Kretz [23]). Kyanite and sillimanite are unstable and are armoured by muscovite, staurolite is often enclosed in garnet poikiloblasts. Sillimanite-bearing gneisses have been found in the Gorphung Khola section at the top of Formation 1; in the gneisses, sillimanite is elongated parallel to the foliation, around the microlithons constituted of Ky armoured with Ms (Fig. 2) or of garnet poikiloblasts. Muscovite and biotite flakes armouring the sillimanite, elongated parallel to the foliation, represent a retrograde greenschists facies metamorphism.

Few dozen meters of white marbles, calc-silicate gneisses, with minor amounts of pelitic and psammitic rocks, follow upward (Formation 2 [24]). Few meters, up to some dozen meters, of orthogneisses and migmatitic gneisses constitute Formation 3 [24]. Migmatitic gneisses are intruded by tourmaline-bearing and leucogranite dykes. The top of the sequence is made up by calcsilicate-bearing marbles. The thickness is nearly 0.5–1 km.

Calcsilicates are occasionally intercalated in the gneisses, containing the stable general assemblage Qtz+Pl+Kfs+Cpx+Ep+Scp+Grt+Bt+Ms±Cc±Pl±Hbl (accessory minerals: tourmaline, rutile, titanite, apatite, zircon and FeTi oxides).

The marbles contain the stable general assemblage Cc+Cpx+Bt±Pl±Scp and accessory minerals: titanite, tourmaline, apatite, rutile, zircon, and FeTi oxides.

Compared to the section of eastern Nepal where the HHC reached thickness of more than 10 km, in the study area the HHC shows a reduced thickness (from 2 to 5 km).

The main fabric is a D2 mylonitic fabric, characterised by shear band cleavages (sensu Passchier and Trouw [26]). Preferred orientation of the metamorphic minerals (Bt, Ms, Ky, Sil) and dynamically recrystallised quartz mark the main schistosity (S2). Sometimes kyanite, muscovite and biotite are bent along shear bands. Kinematic indicators constantly indicate a top-to-the-southwest sense of shear. S2 schistosity strikes NW–SE and dips 30–60° toward the northeast (Fig. 3). The L2 stretching lineation trends N20–30° and plunges toward the northeast (Fig. 3). An earlier deformation phase is sometimes preserved as relict in F2 fold hinges, in S2 microlithons and as internal foliation in porphyroblasts.

4 Tibetan Zone

The bottom of the TZ is made up by impure limestones, calcschists and quartzites belonging to the Dhaulagiri Formation [12], characterised by the metamorphic assemblage, Cal+Qtz+Ms+Bt±Chl±Scp indicating greenschist facies conditions.

Three deformation phases have been recognised in the lower part of the TZ. D1 deformation phase shows an S1 penetrative foliation affecting the sedimentary bedding. S1 is best developed in the more pelitic layers, where it is a continuous foliation. It is associated to the syn-kinematic crystallisation of quartz, calcite, muscovite, biotite, chlorite, and oxides. In the more competent layers, S1 is a spaced, rough, or sometimes anastomosing cleavage. It is axial plane of open to tight folds. It trends mostly NW–SE and assumes variable dipping from sub-horizontal to 80–85° both toward the northeast and the southwest (Fig. 3), as a result of the later tectonic events. F1 fold axes and intersection lineation between S0 and S1 surfaces trend mainly NW–SE. Nevertheless, it has not been possible to surely detect the original facing of F1 folds.

D2 deformation is characterised by an S2 cleavage ranging from a continuous foliation to a crenulation. S2 foliation strikes NW–SE and dips, mostly, from 20 to 40° toward the northeast (Fig. 3). It is axial plane of asymmetric F2 folds showing a vergence toward the northeast (Figs. 4 et 5). One of the most striking kilometre-scale F2 fold has been observed in the southern slope of Mt. Kang Chunne (Fig. 1).

A2 axes show variable orientations, but they mostly trend NW–SE dipping a very few degrees toward the northwest.

Going upwards in the sequence, S2 foliation is progressively less developed ranging from a zonal to a discrete crenulation cleavage. Syn-kinematic recrystallisation of white mica has been rarely observed. The growth of millimetre-size biotite porphyroblasts is post-D1 and syn- to post-D2. S2 foliation is affected by a weak S3 crenulation cleavage axial plane of large, open upright folds.

The lower portion of the sequence is intruded by tourmaline leucogranite dikes, deformed by the D2 phase (Fig. 6).

Going down from the upper portion of the TZ to the contact with the HHC, the metamorphic grade increases [1,16,19,32]. At the same time, the deformation mechanisms change from low temperature deformation to crystalline plasticity. In the upper part, pressure solution predominates, affecting shell fragments as well as detrital grains in impure limestones. The foliation is here millimetre-spaced. Approaching the marbles, the foliation becomes pervasive and quartz and calcite grains accommodate deformation by crystal plasticity showing increasing aspect ratios. They show undulatory extinction, mechanical twins, and dynamic recrystallisation. In the basal part, deformation increases and elongated ribbon calcite crystals are frequently found. A grain shape preferred orientation progressively develops toward the boundary with the HHC, until grains are parallel to each other, marking the main foliation.

5 The detachment

The upper part of the HHC and the lowest portion of the TZ are made by marbles. However, they are characterised by different metamorphic evolutions, but they are not easily separable in the field at a first glance. The maximum metamorphism reached by the marbles at the base of the TZ is the biotite zone of the greenschist facies. On the contrary, the underlying diopside-bearing marbles of the HHC show amphibolite and retrograde greenschist metamorphisms. This highlights a different metamorphic evolution of the two tectonic units that have been tectonically coupled.

A late- to post-tectonic increase in temperature is testified by the growth of millimetre-size biotite porphyroblasts [13], which tends to destroy the high-strain fabric.

In the study sections, the sedimentary sequence of the TZ is affected by centimetre- to kilometre-scale asymmetric F2 folds, recognised above the contact with the HHC. They are well developed in the first 3–5 km of the TZ and their vergence is always toward the north. F2 asymmetric folds point to a back sliding toward the northeast, affecting the basal part of the TZ.

These kinds of fold have been recognized elsewhere in the TZ, such as the Annapurna range [1,5,6,8,22,32] and they have been put in close relation to the top-down to the NE extension affecting the boundary between HHC and TZ [1,2,4–6,8,22,32].

In addition, the HHC presents a uniform monoclinal attitude of the main schistosity, contrasting with the widespread development of D2 north-verging kilometre-scale asymmetric folds affecting the TZ (Fig. 5). Kinematic indicators are recognised at the boundary between HHC and TZ. They are shear bands, boudinaged and delta-type rotated pegmatite dikes intruded in the carbonate sequence pointing to a top-to-the-northeast sense of shear (Fig. 6).

The above evidences suggest the presence of a large zone (thickness nearly 5 km), where deformation linked to top-to-the-northeast extensional tectonics seems to be diffused. We attribute to this zone the same structural significance of the STDS, even if it is characterised by a much wider distribution of deformation respect than that recognised in the ductile shear zones of the STDS [1,2,4–6,8,22,32].

The crystalline marbles, attributed entirely to the HHC by Fuchs [12], have been divided into two parts, each one attributed to a different tectonic unit. The lower part, showing an amphibolite-facies calcsilicate assemblage, is attributed to the HHC, whereas the upper portion, affected only by greenschist-facies metamorphism, is attributed to the TZ, underlying the Dhaulagiri Limestone (Fig. 3).

The geological and structural features of the Lower Dolpo are thus comparable to those recognised in the Kali Gandaki area in central Nepal [32]. The lower portion of the crystalline marbles shows strong similarities and the same structural position as the Larjung Formation [8] in the Kali Gandaki, regarded by others as part of the HHC [32].

In addition, the upper crystalline marbles have the same geometric position, metamorphic grade, structural and lithologic features as the North Col Formation described in the Mt. Everest area, lying above the lower ductile extensional shear zone of the STDS [6,28,35].

A low-angle fault zone, marking the contact between TZ and HHC, has been also reported by Garzanti et al. [17] in the Do-Tarap area, few kilometres southeast of the study area (northeast of Tarakot). This could confirm the composite nature of the STDS, characterised, also in western Nepal, by ductile and brittle fault zones, as documented in other areas of the Himalayas [6,29].

6 Conclusions

Geological investigations along the Lower Dolpo highlight the following features:

- (a) the HHC has a monoclinal attitude of the main schistosity, contrasting with the widespread kilometre-scale northeast-verging folds in the overlying metasediments of the TZ;

- (b) the HHC shows a highly reduced thickness (2–5 km) with respect to the other sections in central and eastern Nepal, particularly in the uppermost portion;

- (c) the different tectonic and metamorphic history of the marbles at the base of the TZ compared with the marbles at the top of the HHC;

- (d) in the TZ the strain increases toward the boundary between HHC and TZ;

- (e) the lower part of the TZ is characterised by widespread northeast-verging F2 folds affecting a previous continuous foliation developed under low-grade metamorphic conditions.

All these features allow to identify and to map an extensional shear zone in Lower Dolpo, related to the STDS, between the crystalline marbles of the HHC and the base of the TZ.

Acknowledgements

Fieldwork in western Nepal was financially supported by National Research Council of Italy (P.C. Pertusati) and University of Pisa (R. Carosi). A. Pêcher is acknowledged for constructive criticism and helpful comments on the manuscript.