Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

À la fin de l'Ordovicien, la plate-forme nord-gondwanienne est à plusieurs reprises couverte par des glaciers [1–3,6,7,18]. En Libye, dans le bassin de Murzuq, les dépôts résultants sont globalement subdivisés en une formation inférieure argileuse (Melaz Shuqran) et une formation supérieure gréseuse (Mamunyiat) [12,14]. Dans le détail, une telle subdivision lithostratigraphique ne peut être maintenue [15]. Ainsi, des levés dans la région du Gargaf [4,5] montrent : (1) que les sédiments glaciaires se subdivisent en plusieurs unités de dépôt limitées par des surfaces d'érosion liées à la formation de paléovallées ; (2) que chaque unité comprend généralement une succession à dominante argileuse à la base et à dominante sableuse au sommet ; (3) qu'il existe une relation entre des directions structurales anciennes, l'orientation des paléovallées et l'existence de dépocentres associés à des failles actives pendant la glaciation.

2 Paléovallées glaciaires

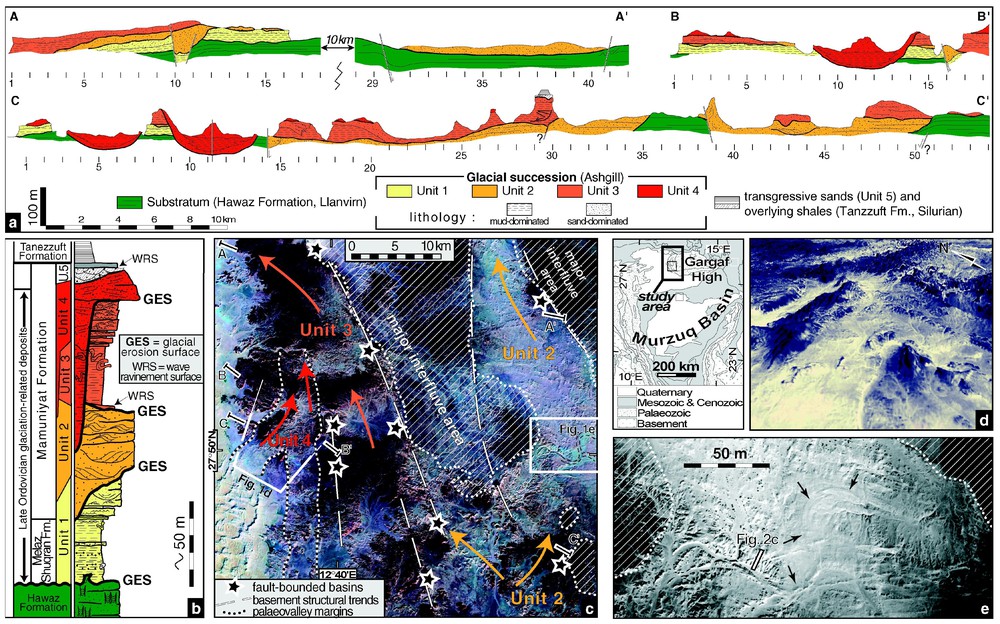

Au sein de la succession glaciaire de la région du Gargaf, quatre unités de dépôt verticalement superposées et latéralement juxtaposées sont définies (Fig. 1a et b). L'unité 1 surmonte une surface basale érosive, régionalement plane mais localement irrégulière, recoupant différents horizons préglaciaires localement très déformés. La surface basale de l'unité 2 dessine des paléovallées de plusieurs kilomètres de large, latéralement limitées par des zones faillées ou déformées (Fig. 1a, profils A30–41, C14–35 et C39–51). La surface basale de l'unité 3 dessine des paléovallées comparables à celle de l'unité 2 (profil C8–30). L'unité 4 comble des vallées beaucoup plus étroites (3–5 km) et encaissées (> 150 m) (profils B9–14, C3–7 et C9–14 ; Figs. 1c–d et 2a).

(a) Selected cross-profiles showing the stratigraphic architecture of the Late Ordovician glacial record in the Gargaf area. (b) Synthetic log of the glaciation-related units with location of the main glacial erosion surfaces. (c) Satellite image (available at http://zulu.scc.nasa.gov/mrsid/mrsid.pl), of part of the western Gargaf area with location of the cross-profiles in (a), outlines of the palaeovalleys of Units 2, 3, and 4, and the distribution of the fault-controlled depocentres relative to the regional structural trend and to palaeovalleys. (d) 3D view of the confluence of two palaeovalleys in Unit 4 (location and scale in Fig. 1c). (e) Aerial photograph of a meander belt complex in Unit 2 (location in Fig. 1c).

(a) Profils 2D illustrant l'architecture stratigraphique de la succession glaciaire fini-ordovicienne dans la région du Gargaf. (b) Log synthétique des unités « glaciaires » avec localisation des principales surfaces d'érosion. (c) Vue satellitaire partielle (disponible à http://zulu.scc.nasa.gov/mrsid/mrsid.pl) de la partie occidentale du Gargaf, avec la position des profils 2D de (a), le tracé des paléovallées des unités 2, 3 et 4, et la distribution spatiale des dépocentres sur failles par rapport aux structures linéamentaires et aux paléovallées. (d) Vue en 3D, montrant la confluence de deux paléovallées de l'unité 4 (localisation et échelle, Fig. 1c). (e) Photographie aérienne d'un complexe de méandres dans les dépôts de l'unité 2 (localisation sur la Fig. 1c).

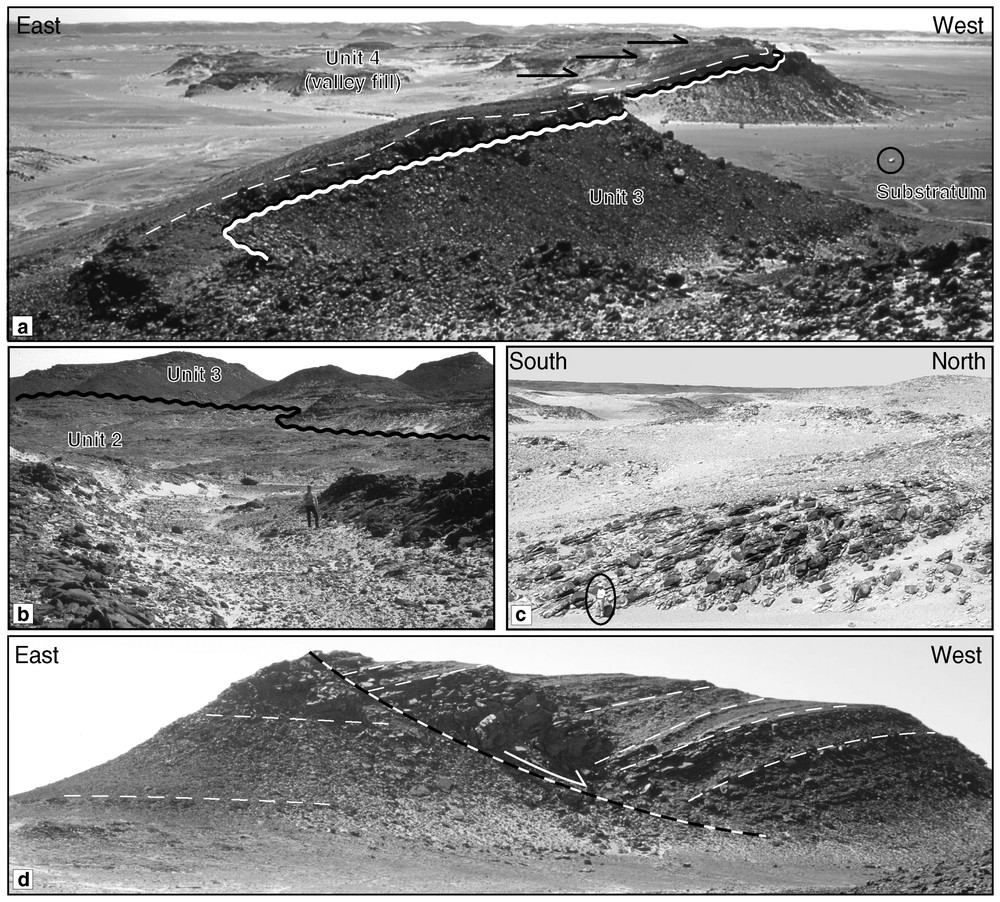

(a) Western margin of a north–south-oriented palaeovalley of Unit 4; the bulk of the valley fills onlaps (black arrows) onto sandstone beds (dashed line) that drape the erosional surface (wavy line) (circled car for scale). (b) Glacial erosional surface at the base of Unit 3 deposits, along which intraformational striated surfaces (not shown) were found within the upper part of Unit 2 deposits; person for scale, standing within a subglacial channel. (c) Epsilon-cross-stratification within Unit 2, of laterally accreted meander-bar deposits (encircled person for scale, location of the profile in Fig. 1e). (d) Roll-over structure within a Unit-3 depocentre (cliff height: 70 m).

(a) Bordure occidentale d'une paléovallée d'orientation méridienne appartenant à l'unité 4; l'essentiel du remplissage repose en onlap (flèches noires) sur des grès (ligne tiretée) moulant la surface d'érosion (ligne ondulée) (véhicule cerclé pour échelle). (b) Surface d'érosion glaciaire à la base de l'unité 3, le long de laquelle ont été trouvées des surfaces striées intraformationelles au sein des grès de l'unité 2; personnage pour échelle, au milieu d'un chenal sous-glaciaire. (c) Structures d'accrétion latérale d'une barre de méandre au sein de l'unité 2, reflétant la construction d'une barre de méandre (personnage cerclé pour échelle, localisation du cliché sur Fig. 1e). (d) Structure en roll-over au sein d'un dépocentre structural de l'unité 3 (hauteur de la colline: 70 m).

L'origine glaciaire des surfaces d'érosion marquant la base des unités de dépôt peut être déterminée par les structures associées ou par la nature des sédiments sus-jacents. La surface de base de l'unité 1 est associée à des déformations importantes affectant les sédiments préglaciaires et elle est directement recouverte par des grès argileux microconglomératiques à rares galets exotiques striés. Des surfaces striées, fractures en gradin, plis, roches moutonnées, chenaux sous-glaciaires (Fig. 2b) marquent la surface de base de l'unité 3. Bien que la morphologie des surfaces basales des unités 2 et 4 soit caractéristique d'une érosion glaciaire, la mise en place de faciès de haute énergie dans le remplissage sus-jacent en a oblitéré les structures glaciogéniques. Toutes ces vallées ont été creusées dans des sédiments apparemment peu lithifiés, comme le suggère l'abondance des déformations et des figures d'échappement d'eau affectant les sédiments tant glaciaires que préglaciaires.

3 Les unités de dépôt

Mis à part les quelques galets striés d'origine exotique dispersés dans des grès argileux microconglomératiques et les structures d'érosion et de déformation sous-glaciaires associées aux limites d'unités, les indices purement glaciaires sont rares. Cependant, la complexité de la sédimentation essentiellement (glacio-)marine et fluviatile est caractéristique de l'environnement glaciaire : variations latérales de faciès rapides, nombreuses surfaces d'érosion internes, structures chenalisantes et paléovallées, structures indiquant de fortes décharges sédimentaires.

L'unité 1 (30–70 m), essentiellement argileuse à la base, avec quelques rares galets striés isolés et intercalations gréseuses à litage oblique en mamelons, passe vers le haut à des bancs gréseux à laminations planes ou ondulées et rides de vagues. Cette succession est interprétée comme le passage d'une sédimentation glacio-marine distale à des dépôts sableux de plate-forme marine dominée par les tempêtes.

L'unité 2 (<70 m), constituée essentiellement de grès fins à grossiers, montre de très fortes variations latérales de faciès, avec notamment des bancs tabulaires à laminations planes, structures d'échappement d'eau et intercalations silto-gréseuses finement laminées passant à des unités amalgamées faites de mégarides chevauchantes. L'existence de surfaces d'accrétion latérale de 5 à 20 m de hauteur (Fig. 2c), recoupées par des structures en chenaux et la marque en photographie aérienne de ceintures de méandre parfaitement préservées (Fig. 1e), permettent d'interpréter les dépôts de l'unité 2 comme le résultat de l'agradation d'un système fluviatile méandriforme [17]. Les bancs tabulaires et les mégarides chevauchantes représentent, dans ce schéma, des dépôts de débordement de chenaux liés à des phénomènes de crues proglaciaires.

L'unité 3 est constituée par la juxtaposition de successions grano-croissantes débutant par des faciès argileux à figures de tempêtes, en onlap sur des structures de déformation sous-glaciaires, ou sur un mince niveau gréseux basal bioturbé et remanié par la houle. Ces dépôts argileux passent vers le haut à des faciès gréseux où alternent bancs à laminations planes et lits plus fins à rides. Des corps chenalisants de largeur hectométrique existent localement. Cette unité est interprétée comme le résultat de la progradation de lobes deltaı̈ques succédant à un épisode transgressif consécutif à un retrait glaciaire.

Le comblement des paléovallées de l'unité 4 (Fig. 1d) débute par un grès grossier, localement fortement déformé, qui moule les flancs raides de la vallée (Fig. 2a). Au-dessus reposent successivement en onlap des grès fins argileux massifs à figures d'échappement d'eau et plissements gravitaires, puis des bancs de grès granoclassés, et finalement des grès grossiers à litages obliques formant de grandes structures chenalisantes sinueuses amalgamées. L'encaissement des vallées, dont les flancs sont moulés par des grès grossiers à la base, et la succession grano-croissante sus-jacente, suggèrent une érosion et un remplissage initial par des eaux de fonte sous-glaciaires d'un système de vallées en tunnel [8,10,13], colmaté ensuite par la progradation d'un cône sub-aquatique proglaciaire évoluant vers un environnement fluviatile.

4 Dépocentres et failles associées

À l'échelle régionale, l'orientation des paléovallées et la localisation de dépocentres apparaissent liées aux grands linéaments structuraux NNW–SSE et nord–sud héritées du socle (Fig. 1c). Les dépocentres, identifiés dans les unités 2 et 3, correspondent à des zones d'accumulation à subsidence différentielle et d'extension kilométrique. Un premier type de dépocentres, caractérisé par un remplissage très grossier, montre un épaississement au droit de failles affectant les sédiments de l'unité 1 et le substratum préglaciaire, mais scellées par l'unité 3 (Fig. 1a, profils A10–11, B16 et C14). Des brèches intraformationelles ainsi que des volcans de sable jalonnent leur bordure faillée. Un second type de dépocentre montre des géométries en onlap et en roll-over au sein de l'unité 3 (profil C30, Fig. 2d). Bien que de tels dépocentres puissent résulter d'instabilités gravitaires sur des fronts de delta ou sur les bordures de la vallée [9], la plupart de ceux-ci sont alignés le long d'accidents affectant l'ensemble de la couverture sédimentaire (Fig. 1d).

Des déplacements verticaux n'excédant pas 50 m et une distribution spatiale en relation avec des structures linéamentaires suggèrent, pour l'origine de ces dépocentres, un rejeu en régime extensif d'accidents panafricains provoqués par l'interaction entre le champ de contraintes régional et des contraintes flexurales d'origine glacio-isostasique [11].

5 Conclusion

L'architecture sédimentaire des dépôts glaciaires (sensu lato) est contrôlée par la répétition de périodes d'érosion glaciaire et par la formation de dépocentres liés à la réactivation par glacio-isostasie d'un réseau de failles préexistant. Cela se traduit par des unités sédimentaires discontinues et juxtaposées remplissant des paléovallées et paléodépressions. Chaque surface basale d'érosion représente une avancée majeure des fronts glaciaires sur la plate-forme, atteignant au moins le Nord du Gargaf (>28°S). L'évolution de la morphologie de ces surfaces d'érosion glaciaire, depuis une surface à peu près plane jusqu'à des vallées fortement encaissées peut être interprétée, dans un schéma de retrait glaciaire généralisé, comme le reflet d'un changement de la position relative du Gargaf par rapport à la limite septentrionale de chaque maximum glaciaire. La transition d'origine climatique ou zonale entre un glacier à base froide et un glacier à base tempérée [16] pourrait expliquer notamment l'évolution vers une importante production d'eau de fonte sous-glaciaire entraı̂nant la formation de vallées en tunnel avant le dépôt de l'unité 4. L'orientation des paléovallées, parallèle aux grandes failles de direction nord–sud ou NNW–SSE et les déformations syn-sédimentaires le long de leurs flancs, suggèrent que les zones de faiblesse structurale et/ou que la distribution des dépocentres a/ont pu servir de guide à l'érosion glaciaire après le dépôt de l'unité 1.

L'enregistrement glaciaire, comprenant essentiellement des dépôts fluviatiles à marins peu profonds, reflète des environnements relativement distaux par rapport aux fronts glaciaires. Ils succèdent à des phases importantes de retrait des fronts glaciaires vers le sud et correspondent à la mise en place de conditions régionales interglaciaires. Chaque unité a été déposée pendant un temps assez court correspondant à une fraction d'un cycle climatique glaciaire-interglaciaire. Ces unités forment donc des unités allostratigraphiques qui sont corrélables sur l'ensemble du Bassin de Murzuq et au-delà sur la plate-forme nord-gondwanienne [7]. L'architecture stratigraphique est celle d'un système caractérisé par de fréquentes « cannibalisations ». Une accommodation sédimentaire peu importante pendant la durée de la glaciation contraste avec les fortes accommodations régnant lors du dépôt de chaque unité de dépôt correspondant au remplissage d'une paléovallée.

1 Introduction

During the Latest Ordovician, the western Gondwana was located in southern high latitudes. It was covered by an extensive ice sheet centred in Central Africa, the front of which fluctuated throughout present-day West and North Africa, and Arabia [1–3,6,7,18]. In Libya, the Late Ordovician glacial record of the Murzuq Basin is generally subdivided into basin-wide lithostratigraphic units: the lower mud-dominated Melaz Shuqran Formation and the upper sand-dominated Mamuniyat Formation [12,14]. However, detailed regional studies do not support this subdivision [15]. In the Gargaf area in the northern part of the basin, field work based on aerial photographs and geological mapping [4,5] shows that: (1) the glaciation-related successions can be subdivided into several depositional units bounded by unconformities related to the formation of glacial palaeovalleys, (2) each depositional unit comprises a coarsening-up succession grading from mud-dominated into sand-dominated deposits, and (3) relationships exist between the inherited regional structural trends and the location of the main valleys, glacial depocentres, and syn-glacial fault-controlled structures.

2 Glacial palaeovalleys

Four depositional units, which are vertically superimposed as well as laterally juxtaposed, have been defined within the Upper Ordovician glacial deposits in western Gargaf (Fig. 1a and b). A fifth transgressive unit, not described in this paper, was deposited during late-glacial time before the deposition of the Silurian shales.

Unit 1 is of large lateral extension and rests on a relatively flat surface at regional-scale. Although this basal surface is rarely visible, landscape observation and mapping clearly show that the contact is erosional, as indicated by local shallow and wide depressions cut into different horizons of the Lower to Middle Ordovician sandstones that are in place highly deformed below the surface. The lower bounding surface of Unit 2 coincides with wide palaeovalleys up to 20 km in width, 100 m in depth and more than 60 km in length. These palaeovalleys are laterally bounded by faulted and/or folded zones affecting both the pre- and syn-glacial deposits (Fig. 1a, profiles A30–41, C14–35 and C39–51). Unit 3 rests on Unit 2, Unit 1, or locally on the pre-glacial sandstones (Hawaz Formation). Its lower bounding surface forms palaeovalleys similar in extension to those of Unit 2 (profile C8–30) and is associated with well preserved subglacial deformation structures. Unit 4 corresponds to the filling of narrow palaeovalleys up to 150 m in depth and less than 5 km in width, deeply incised in the previous units and pre-glacial sandstones (profiles B9–14, C3–7 and C9–14) (Figs. 1c–d and 2a).

The glacial origin of the bounding surfaces can be asserted from the associated structure and/or from the nature of the overlying deposits. Direct evidence of glacial erosion exists for the basal surfaces of Units 1 and 3. In occasional exposures of bounding surface 1, preglacial sandstones are highly deformed and overlain by glaciomarine microconglomeratic argillaceous sandstones including rare striated exotic pebbles. Intraformational deformation structures including striated ‘décollement’ planes, Riedel shear step fractures, folds, ‘roches moutonnées’, or subglacial channels (Fig. 2b) point to subglacial shearing and erosion along the lower bounding surface of Unit 3. No direct evidence of glacial erosion was found along bounding surfaces of Units 2 and 4. However, in both cases the surfaces are overlain by high-energy shallow marine or fluvial sandstones, which may have eroded the pre-existing glaciogenic features.

All palaeovalleys were most probably incised within unlithified sand or mud, as suggested by abundant soft-sediment deformation structures affecting both glacial and preglacial deposits.

3 Depositional units

Within the depositional units direct evidence of glacial processes is inferred from occasional striated exotic dropstones and subglacial deformation structures associated with bounding surfaces. In addition, the bulk of the sedimentary record, which corresponds to fluvial and shallow-marine depositional environments, is characteristic of glacial conditions as shown by the complex nature of the facies associations, internal unconformities, deformation structures, large-scale channels, palaeovalleys and evidence of high-sediment discharge and dump sedimentation.

3.1 Description

Unit 1 is made up of a basal mud-dominated succession (30–70 m) overlain by a coarsening-up sand-dominated succession (10–15 m). The mud-dominated succession consists of massive, microconglomeratic argillaceous sandstones including rare exotic striated pebbles, sharply overlain by laminated silty shales. The latter comprises lenticular or laterally extensive beds of fine-grained sandstones with wave or current ripples and small-scale hummocky cross stratifications. Slump and load structures were also observed. The sand-dominated succession rests upon the mud-dominated one with either an erosive or progressive contact. It is made up of well-sorted medium-grained sandstone beds with horizontal to wavy laminations, and graded beds passing upward into fine-grained wave-rippled sandstones.

Unit 2 (<70 m) is made up of fine- to coarse-grained sandstones, characterized by rapid (kilometre-scale) lateral facies changes whose relationship is generally difficult to trace and interpret. Extensive, several-metre thick, medium- to coarse-grained sandstone sheets, with horizontal to subhorizontal laminations, vertical sheet-dewatering structures, and intervening fine-grained laminated sandstones, pass laterally into amalgamated cosets of 2D or 3D climbing megaripples. Another facies assemblage consists of 5–20 m high large-scale epsilon cross-stratifications (Fig. 2c), coarse-grained channel structures, and fine-grained sandy plugs with current ripples and convolute bedding. A kilometre-scale meandering belt with chute channels can be observed in aerial photographs (Fig. 1e).

Unit 3 is made up of a juxtaposition of delta-like coarsening-up systems, locally affected by syn-sedimentary deformation. The lowermost part of Unit 3 generally consists of laminated mudstones onlapping either the subglacial features preserved on the lower bounding surface, or a decimetre to metre-thick bioturbated and wave-rippled basal sandstone bed. Upwards, micaceous siltstones, with fine-grained sandstone intercalations including waves and polygonal ripples, grade into coarsening-up sandstones. The latter typically display flat laminations in the thicker beds, and wave or current ripples in the intervening thinner beds. Climbing ripples are commonly observed. Isolated, 100 m wide channel structures also occur in places eroding the underlying sediments.

Unit 4 consists of an overall coarsening-up sequence. The incision is initially draped by unsorted coarse-grained sandstones, locally highly deformed, that mould the valley sides, and which are later onlapped by the bulk of the valley infill (Fig. 2a). This infill consists from base to top of: (1) fine-grained muddy sandstones including slump structures, turbidite-like sandstone beds along the valley sides, and conspicuous dewatering structures, (2) an erosion-based succession made up of laterally extensive medium-grained, graded, sandstone beds with abundant dewatering structures, (3) laterally and vertically stacked large-scale sinuous channel structures made up of cross-laminated coarse-grained sandstones. The valley fill is sharply capped by coarse- to very coarse-grained sandstones, which overflow the valley sides and rest on Unit 3 deposits outside the valleys (Fig. 1a, profiles B1–5, C15–20).

3.2 Interpretation

The sediments of Unit 1 are interpreted as distal glacio-marine deposits in front of retreating marine ice fronts, passing upwards into storm-dominated prograding shelf deposits. The valley infill in Unit 2 resulted from the aggradation of sinuous to meandering fluvial systems [17]. This is confirmed by well preserved meander belt structures including variously oriented slightly dipping lateral accretion surfaces, well-bedded overbank deposits and fine-grained sandy plugs. The climbing megaripples, which are characteristic of Unit 2, represent highly concentrated sediment-laden stream-flow deposits, possibly related to outburst events resulting in outflows outside the sinuous channels. The characteristics of the lower bounding surface of Unit 3 suggest both a glacial environment and a transgressive event, and the valley fill deposits record the various stages of the progradation of deltaic lobes, from storm-dominated pro-delta up to the shoreface or fluvial environments. The depth and narrowness of the palaeovalleys of Unit 4, and the presence of the initial valley fill moulding the erosional topography, rather suggest erosion and first infill by sub-ice meltwater flows in tunnel valleys later infilled by proglacial prograding subaquatic fan to delta deposits [8,10,13]. A fluvial braidplain is inferred for the upper part of Unit 4.

4 Fault-controlled depocentres

Small-scale soft-sediment deformation structures are common and distributed throughout the study area. They are either due to subglacial shearing or triggered by local gravity-driven instabilities due to high-rate of sediment supply (e.g., delta sequences in Unit 3). They are not considered as directly related to tectonic events. At a larger-scale, palaeovalleys and local wedge-shaped fault-bounded depocentres are parallel and clearly linked with NNW–SSE and north–south striking faults, which correspond to regional Panafrican tectonic trends in the underlying basement (Fig. 1c).

The local fault-bounded depocentres observed in Units 2 and 3, are up to 50 m thick, 500 m to 2 km wide, and can be traced over several kilometres parallel to the axis of the palaeovalleys.

A first type of fault-bounded depocentre was observed in Unit 2. It is characterized by a medium- to very coarse-grained infill, and shows a significant thickening into the footwall (Fig. 1a, profiles A10–11, B16 and C14). Underlying sediments of Unit 1 are faulted and offset. Overlying deposits belonging to Unit 3 locally seal the fault system. The occurrence of intraformational breccias located at the fault-bounded side of the depocentres suggests the existence of small transient palaeorelief forms. The presence of sand-volcanoes close to the faults indicates overpressure during the infill of the depocentres. Although gravitational processes could be envisaged for the formation of these depocentres, their alignment along the main lineaments (Fig. 1c), and the fact that the pre-glacial substratum is involved in the deformation, strongly suggest a tectonic origin.

A second type of fault-bounded depocentre shows onlap and rollover geometries within well bedded Unit 3 sediments (Fig. 1a, profile C30, Fig. 2d). Faults were not observed cutting across pre-glacial rocks, and a gravity-driven mechanism due to slope instability in delta setting or along valley sides [e.g., [9] appears as the probable triggering mechanism. However, a number of these depocentres are aligned along structural trends as well (Fig. 1c).

Fault-bounded depocentres related to the first type were active during a time range starting after deposition of Unit 1. As they are filled by fluvial sandstones and sealed by sediments belonging to Unit 3, they coincide with the deposition of Unit 2. Depocentres related to the second type were active during the deposition of Unit 3.

The small amount of vertical displacement, which does not generally exceed 50 m, the spatial association with pre-existing lineament orientation of Panafrican origin, as well as the lack of a consistent vergence of the faults bounding the depocentres, suggest that this deformation, occurring during the Late Ordovician glaciation is more likely associated with the reactivation of pre-existing structures during deglaciation events rather than associated to a large-scale tectonic event. The interaction of a crustal stress field with flexural stresses due to ice-sheet loading or to the subsequent removal of ice load results in low-strain either extensional or wrench tectonics [11]. It should be noted that these faults were also reactivated later during the so-called Hercynian event.

5 Conclusion

The architecture of the glacial succession is controlled primarily by successive glacial erosion events resulting in laterally discontinuous and juxtaposed sedimentary units filling palaeodepressions and palaeovalleys. Each of the corresponding basal bounding surfaces represents a major ice-front advance throughout the north Gondwana platform, reaching at least the northern Gargaf (>28°N). The progressive evolution of the shape of the bounding surfaces from a relatively flat regionally extensive surface, to well-defined wide and shallow palaeovalleys, and to narrow and deeply incised palaeovalleys may reflect a change in the position of the Gargaf area relative to the successive maximum northern extension of the ice fronts in an overall glacial retreat. Climatically controlled or subglacial zonal changes [16] from cold-based to warm-based glacier conditions may also explain this evolution and particularly the intense meltwater production during the latest glacial advance resulting in the formation of tunnel valleys. Palaeovalley orientations parallel to the north–south or NNW–SSE striking faults and syn-sedimentary deformation along palaeovalley margins could also suggest that structural weaknesses and/or the distribution of fault-bounded basins may have acted as guides for the glacial erosion processes starting after the deposition of Unit 1. The relationships between regional structural trends inherited from Panafrican lineaments and syn-glacial faults and associated small-scale depocentres suggest glacio-isostatically induced fault reactivation. The latter took part in the complex architecture of the Upper Ordovician deposits of the Gargaf area.

Although sedimentary units are bounded by erosional surfaces of glacial origin, the bulk of the sedimentary succession is made up of fluvial to shallow-marine sediments reflecting pro- to distal glacial environments related to either retreating marine ice-front evolution or interglacial conditions (ice front shifted southward). Each of the sedimentary units was deposited during a short time interval corresponding to a fraction of a climatically controlled glacial cycle. They correspond to allostratigraphic units that should be correlated within the Murzuq Basin and outside throughout the north Gondwana platform [7]. The stratigraphic architecture suggests a low-accommodation depositional system, within which several “cannibalisation” events have occurred through repetitive glacial erosion events. Low-accommodation conditions throughout the whole glaciation contrast with high accommodation conditions that characterise the filling of glacially eroded palaeovalleys by relatively thick (up to 100 m) sedimentary units.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Repsol Exploration Murzuq SA and partners (Total, OMV, Norsk-Hydro). We thank Géoscience Consultant (Bagneux, France) for providing the 3D view of Fig. 1d.