Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

La période crétacée se caractérise à l'échelle globale par la récurrence de niveaux de black shales, déposés pendant ce qu'il est d'usage d'appeler les événements anoxiques océaniques (OAE [2,4,39,40,43,44,55]). Ces OAE coïncident avec des périodes transgressives [30,40], des restrictions des plates-formes carbonatées [2,30,41,49,64] et des excursions positives, voire parfois négatives, du rapport isotopique du carbone des carbonates et de la matière organique [5,13,26,36,38,45,50,56,59,60,64]. Un lien causal a été avancé avec les périodes d'intense activité volcanique, l'augmentation du CO2 et des températures qui en résulte et finalement l'accélération du cycle hydrologique qui permet l'apport de nutriments à l'océan [25,43,44,46,49,60,62,63].

L'objet de cette note est de décrire brièvement les principales caractéristiques d'un court événement anoxique qui s'est développé dans la Téthys méditerranéenne à la fin de l'Hauterivien .

2 Description du niveau Faraoni et de ses équivalents

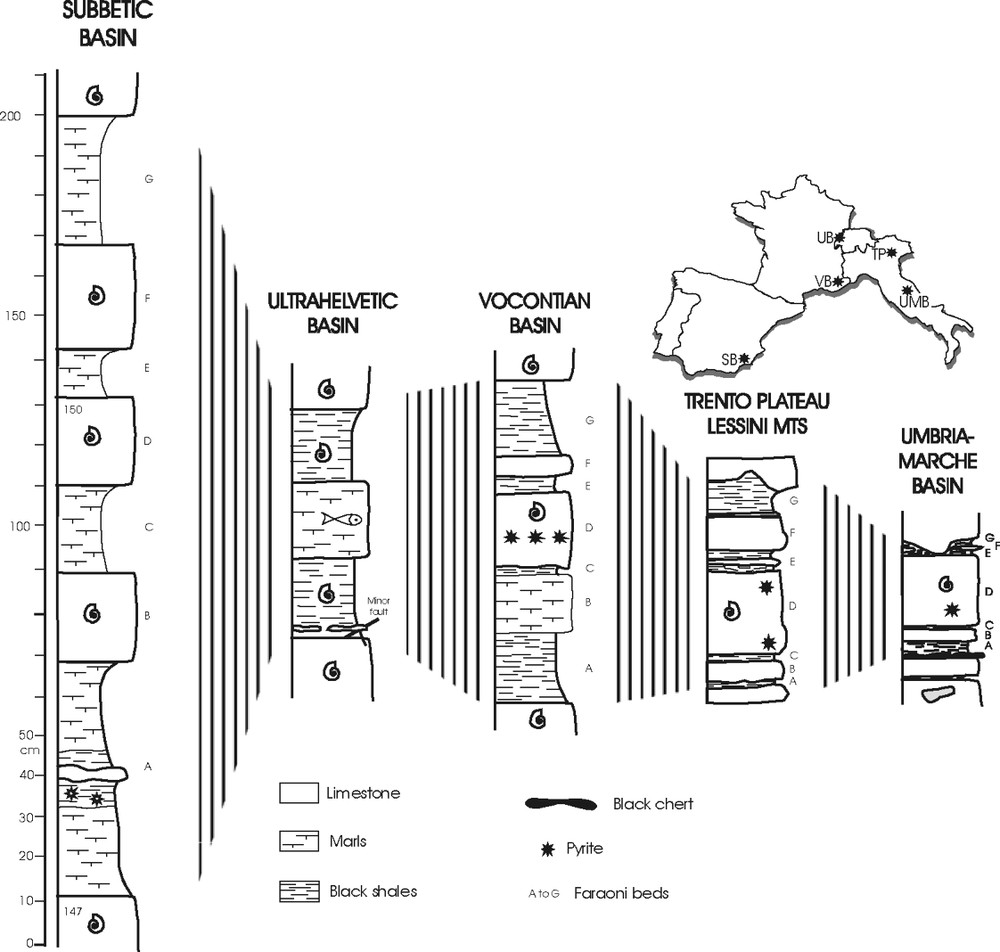

Il y a quelques années, un niveau repère a été décrit dans l'Hauterivien supérieur du bassin d'Ombrie–Marches (Italie centrale) et défini sous le nom de niveau Faraoni [15]. Bien daté par les ammonites (zone à Pseudothurmannia angulicostata, sous-zone à P. catulloi [15,16]) et la magnétostratigraphie (magnétozone M5n, [19]), ce niveau – épais de 25 à 45 cm – se caractérise par un banc calcaire très riche en ammonites, encadré par des black shales renfermant jusqu'à 25% de carbone organique [9,15].

Des équivalents du niveau Faraoni ont été ensuite reconnus sur le plateau de Trente (Italie du Nord [17,28]), dans le Bassin vocontien (Sud-Est de la France [8]), dans les cordillères Bétiques (Sud de l'Espagne [1,21]) et dans le domaine ultrahelvétique en Suisse [10,14]. Outre une grande similitude lithologique (Fig. 1), les indices faunistiques (ammonites, nannofossiles calcaires, foraminifères) sont remarquablement comparables entre ces différents bassins et confirment tous que l'on se situe précisément dans la même tranche de temps. L'analyse cyclostratigraphique des séries pélagiques [29] qui contiennent le niveau Faraoni indique que cet événement a une durée proche de 100 ka.

Comparison of the lithological expression of the Faraoni Event in different Tethyan pelagic basins.

Comparaison de l'expression du Niveau Faraoni dans différents bassins pélagiques téthysiens.

3 Évidences paléontologiques et géochimiques d'un événement anoxique

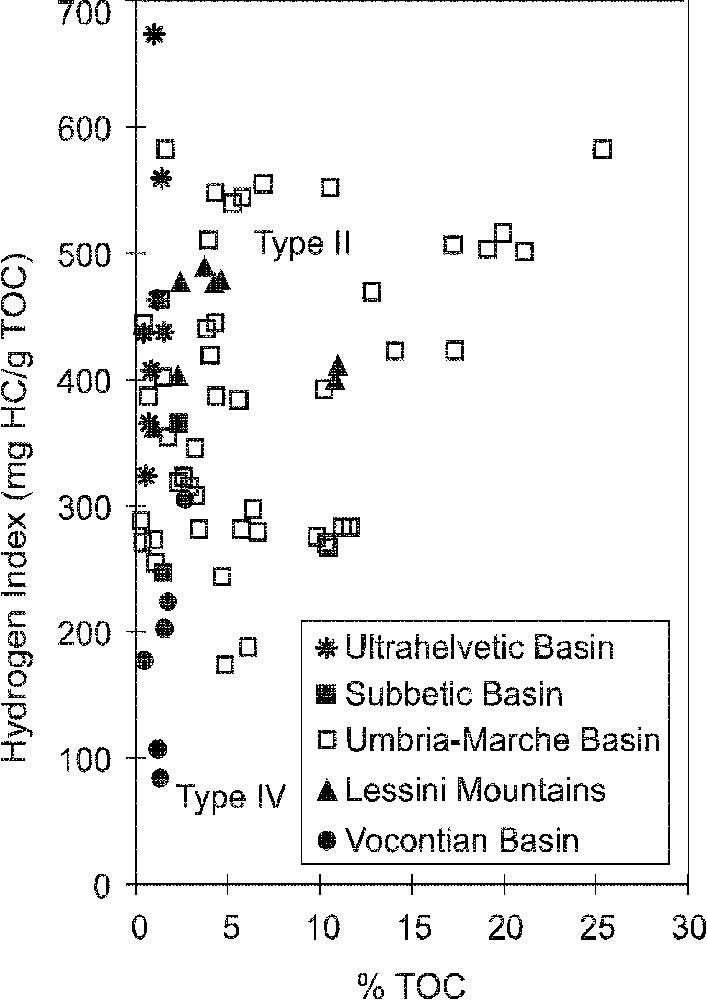

Comme pour la plupart des OAE, l'intervalle fini-Hauterivien correspondant au niveau Faraoni révèle des changements dans l'enregistrement fossile, qui témoignent de modifications paléoécologiques et paléocéanographiques. Les foraminifères benthiques sont généralement rares, voire absents, suggérant une déficience en oxygène des eaux de fond pendant tout ou partie de l'événement. On note une forte diminution des nannoconidés, la disparition du nannofossile calcaire Lithraphidites bollii et une augmentation de l'abondance de Gorbatchikella, foraminifère planctonique aux loges globulaires [20], en coïncidence avec cet événement. Les radiolaires, témoins d'une forte productivité de surface, sont particulièrement abondants et diversifiés. La matière organique est significativement plus abondante dans le niveau Faraoni par rapport aux marnes l'encadrant ; elle est clairement d'origine marine, d'après les analyses géochimiques et palynologiques (Fig. 2) [9,31].

Plot of total organic carbon (TOC) against hydrogen index for black shales of the Faraoni Event in different Tethyan pelagic basins. The Faraoni Level of the Vocontian Basin shows the lowest TOC values with an altered organic matter (Type IV). The Faraoni Level in the other basins, although the points are dispersed on this diagram, is organic-rich (>1 up to 27%) and contains a marine organic matter (Type II).

Diagramme IH–COT des black shales du niveau Faraoni dans différents bassins pélagiques téthysiens. Le niveau Faraoni du Bassin vocontien présente les plus faibles valeurs du contenu en matière organique tendant vers un type IV (altéré). En revanche, malgré la dispersion des points représentés sur ce diagramme, le niveau Faraoni des autres bassins renferme beaucoup de matière organique (>1 et jusqu'à 27%), dont l'origine est marine (type II).

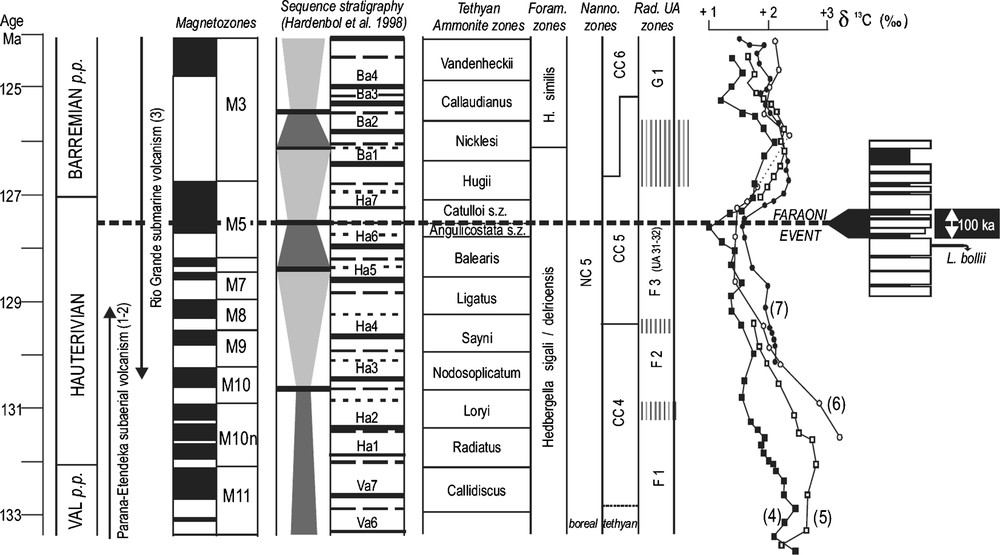

Une petite excursion positive du rapport isotopique du carbone de séries téthysiennes et atlantiques est mise en évidence dans la partie terminale de l'Hauterivien et la base du Barrémien (Fig. 3) suggérant, comme pour les OAE [5,13,45,50,56], une accélération du stockage du carbone organique dans le réservoir sédimentaire juste après l'événement Faraoni.

Stratigraphic chart for the Hauterivian stage, sequence stratigraphy, timing of volcanism in the South Atlantic (1: [58]; 2: [53]; 3 [32]) and selected carbon-isotope curves (4: [24]; 5: [61]; 6: [33]; 7: [42]).

Charte stratigraphique de l'Hauterivien, séquences de second et troisième ordre, extension du volcanisme dans l'Atlantique sud (1 : [58] ; 2 : [53] ; 3 : [32]) et sélection de quelques courbes des variation du (4 : [24] ; 5 : [61] ; 6 : [33] ; 7 : [42]).

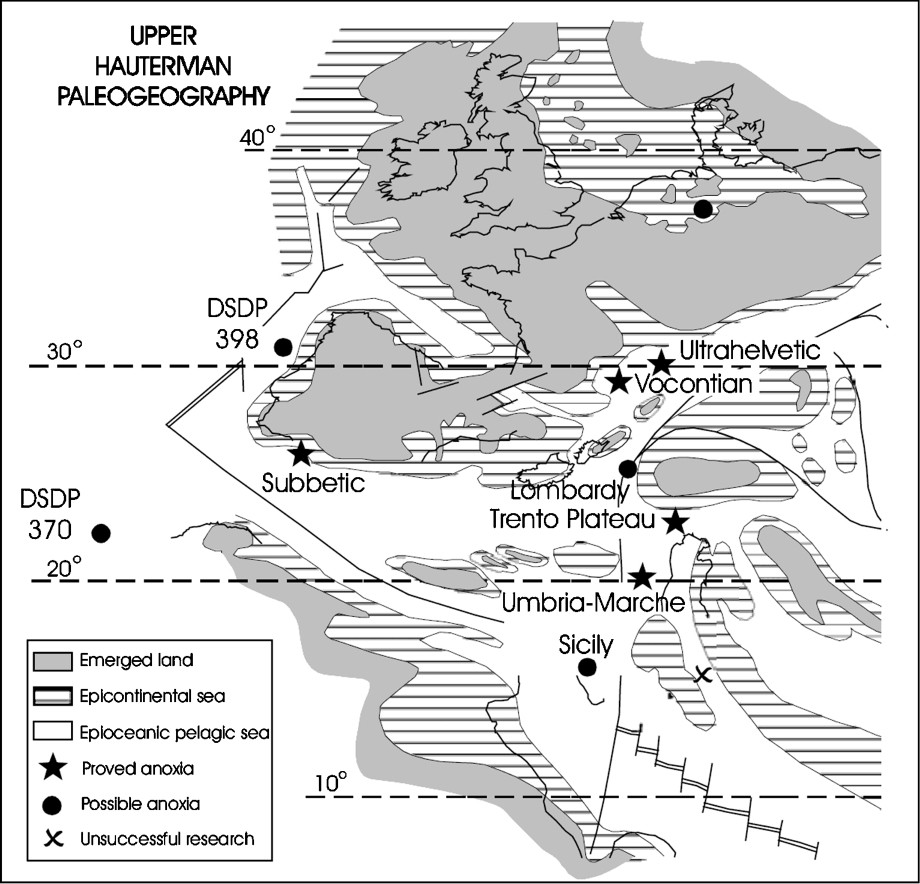

4 Autres enregistrements possibles de cet événement (Fig. 4)

Les recherches d'équivalents du niveau Faraoni dans la zone ionienne (Grèce) n'ont pas été fructueuses jusqu'à présent. En revanche, des équivalents du niveau Faraoni ont été décrits en Lombardie [12] et en Sicile [11]. Dans les sites DSDP de l'Atlantique, seules les données micropaléontologiques (nannofossiles calcaires) et géochimiques (organique et isotopiques) permettent de suspecter la présence de conditions anoxiques vers la fin de l'Hauterivien [3,52]. Dans les bassins septentrionaux d'Allemagne, un enrichissement en matière organique est noté dans les séries de plate-forme au niveau de la zone à Simbirskites discofalcatus, équivalent de la zone à P. angulicostata [51]. Enfin, les enregistrements des variations du rapport isotopique du carbone dans un atoll du Pacifique [42] montre les mêmes tendances que celles mises en évidence dans le domaine téthysien au passage Hauterivien–Barrémien (Fig. 3).

Palaeogeographic map of the Mediterranean Tethys during the Latest Hauterivian (modified from [23]) and location of basins where anoxic conditions were recorded.

Carte paléogéographique simplifiée de la Téthys méditerranéenne à la fin de l'Hauterivien (modifiée d'après [23]) et localisation des bassins où les conditions anoxiques ont été reconnues.

5 Causes possibles de l'événement Faraoni

La fin de la mise en place du trap du Paranà–Etendeka est datée d'environ 131 Ma [22,53,58], ce qui précède d'environ 3 à 4 Ma l'événement Faraoni et ne peut donc en être la cause. Il serait plutôt à rapprocher du pic de production des laves sous-marines du Rio Grande, qui est daté de la magnétozone M5n, soit autour de 127 Ma (Fig. 3) [32]. L'apport de de basalte supplémentaire pendant la durée de l'événement aurait pu suffire à produire le même enchaînement de cause à effet que pour les autres OAE [43,54]. Ainsi, après le pic de production du trap du Paranà–Etendeka, qui correspond à l'événement Weissert [26], l'événement Faraoni correspondrait à la mise en place de la ride de Walvis–Rio Grande.

D'autres causes directes doivent cependant être évoquées, comme la rapide hausse du niveau marin relatif, qui prend place pendant la sous-zone à P. catulloi (mfs Ha6 d'après [35], Fig. 3). La création de nouvelles surfaces épicontinentales, générée par cette transgression, a pu conduire à une augmentation de la productivité primaire, une expansion de la zone à minimum d'oxygène et conduire à la réduction des plates-formes carbonatées, qui est notée à cette époque [30].

Ces deux causes ne sont pas mutuellement exclusives et, comme pour d'autres OAE, il est probable que, pendant une période d'intense activité mantellique, les fluctuations du niveau marin influençaient la mise en place des conditions anoxiques dans les bassins et sur les plates-formes.

6 Conclusions

Des données lithologiques, paléontologiques et géochimiques révèlent que de nombreux bassins pélagiques de la Téthys méditerranéenne ont été propices au développement de conditions déficientes en oxygène à la fin de l'Hauterivien, qui a donc connu un court événement anoxique. Il est fort probable que les mêmes facteurs forçants, à l'origine des événements anoxiques globaux, soient la cause de ce court événement.

1 Introduction

Global oceanic anoxic events (OAEs) – such as the Toarcian, Early Aptian (OAE1a) and Cenomanian–Turonian (OAE2) – represent exceptional episodes of short time duration during Earth's history, which are marked by widespread deposition of organic matter in marine environments and therefore important petroleum source-rocks [2,4,39,40,43,44,55]. They are often accompanied by phases of rapid sea-level rise [39,40], carbonate platform drowning [2,30,41,49,64] and large positive carbon-isotope shifts in both carbonate and organic matter, caused by the storage of isotopically light carbon in sediments [5,13,26,45,50,56,59,60,64]. At the beginning of both the Toarcian and Early Aptian OAEs, a sharp negative shift in has been documented in marine and terrestrial records, and interpreted as the signature of methane clathrate dissociation [36,38]. Causal links have been postulated to periods of intensified volcanic activity, and related increase in atmospheric CO2 and global warming, hence increase in continental weathering and nutrient flux to the oceans [25,43,44,46,49,60,62,63]. Finally, OAEs coincide with biotic turnover [34,65].

Other anoxic events, which also promoted widespread deposition of organic carbon-rich marine sediments, are recognized within the Cretaceous. However, these events are not truly global, although they are usually labelled as OAEs [5,26]. They are as follow: the Weissert Event (Valanginian–Hauterivian), OAE1b (Early Albian), OAE1c (early Late Albian) and OAE1d (Latest Albian) and OAE3 (Santonian–Coniacian).

The purpose of this paper is to briefly describe some salient features of a short-lived anoxic event that took place during the Late Hauterivian in the Mediterranean Tethys.

2 Age and lithology of the ‘Faraoni Level’ and its equivalents

Several years ago, Cecca et al. [15] described an Uppermost Hauterivian marker level in the Maiolica Formation of Umbria–Marche Apennines in central Italy. This marker level, named Faraoni Level, was recognized along 26 sections, where it shows a remarkably constant lithological expression. Ranging from 25 to 42 cm in thickness, the Faraoni Level is composed of an ammonite-rich limestone bed sandwiched between black shales and thinner limestone beds. Its lower boundary is generally characterised by the occurrence of a more or less continuous black chert layer, overlain by seven beds, lettered A to G, which compose the Faraoni Level itself (Fig. 1).

The Faraoni Level lies within the Pseudothurmannia catulloi ammonite subzone, the Hedbergella sigali–H. delrioensis planktonic foraminiferal zone, the Galvinella sigmoicostata benthic foraminiferal zone, the CC5 (NC 5c) nannofossil zone and the F3 (UA 31–32) radiolarian zone [16,20]. In many sections, the last occurrence of the calcareous nannofossil species Lithraphidites bollii is just below the Faraoni Level [20]. This level lies in the M5n (equivalent of CM4) magnetozone [19]. All datings indicate that the Faraoni Level took place in the Latest Hauterivian .

Subsequently, a strict equivalent of the Faraoni Level was recognised in northern Italy within the Biancone Formation cropping out in the eastern edge of the Trento Plateau [17] and in the Lessini Mountains [28]. The upper part of the Faraoni Level (beds E to G) is missing in the Trento Plateau and its beds A and C are not truly black shales, whereas the Faraoni Level is complete in the Lessini Mountains (Fig. 1). The Faraoni Level was later documented in the Vocontian Basin (southeastern France) along the Vergons section [8], and is now recognized throughout the entire basin. Although twice as thick, the Faraoni Level from southeastern France displays a remarkable similarity in lithologic expression, compared to the Italian record (Fig. 1).

After these early descriptions, the fundamental philosophy has been to search for sedimentary anomalies through other Upper Hauterivian sections from the Mediterranean realm. Up to now, searching in the Ionian basin was unsuccessful, whereas recent fieldwork suggests the possibility of having an equivalent to the Faraoni Level in the Subbetic (Rio Argos section) and Ultrahelvetic (Veveyse de Châtel and Voirons sections) Basins. Palaeontological constraints are available in both basins and indicate the same ammonite subzone for the Subbetic Basin [1,21] and the Ultrahelvetic Basin [14]. The lithological succession of the Faraoni Level from Subbetic Basin is comparable to the Italian and French occurrences, but its thickness reaches 2 m (Fig. 1). The lithological expression is different in Switzerland where a 40-cm-thick interval of laminated black shales could be the Faraoni Level equivalent (Fig. 1) [10].

The deposition of such a remarkable organic-rich interval over a wide area suggests that palaeoceanographic changes took place at the end of the Hauterivian in the Mediterranean Tethys. The duration of this event, called here ‘Faraoni Event’, is estimated between 80 to 100 ka according to cyclostratigraphical analyses of the different sections. If we assumed that the basic marly-limestone alternation represents a precessional cycle, as demonstrated for most of the Cretaceous pelagic successions in which the Faraoni Level was recognized [29], the four doublets of the Faraoni Level (7 beds + the black siliceous chert or the limestone bed at its base) give such a duration.

3 Palaeontological and geochemical evidence arguing for an anoxic event

Although not entirely clear in terms of palaeoecology and palaeoceanography, marked changes in the palaeontological record have been observed around the Faraoni Level through the different sections described above. The lack of benthic foraminifera may indicate that sea-floor conditions were unsuitable for their development, whereas the planktonic foraminiferal assemblages are marked by an increase in abundance of Gorbatchikella specimens. This globular form is considered as an indicator of warm sea-surface temperatures [20]. A decrease in nannoconids is noted in the black shale layers through the Faraoni Level [8,20]. An increase in the relative abundance of radiolarians occurs just below and within the Faraoni Level. However, no major change in assemblage composition has been recognized, in contrast to what was observed through OAE1a and OAE2 [27]. Since an important turnover has been recognized in the Late Hauterivian ammonite faunas of the Mediterranean Tethys [37], the Faraoni Level, which is characterized by an exceptional diversity, is regarded as a transitional phase of this renewal [18].

In many localities, the clayey beds of the Faraoni Level (A, C, E, and G) are dark brown to black, organic-rich, millimetre-laminated, implying deposition in anoxic or hypoxic conditions. The sulphur-organic carbon relationship for the Faraoni Level in Umbria–Marche Basin also indicates dysoxic to anoxic conditions [9], allowing the preservation of organic matter. Hence, the organic carbon content of the black shales fluctuates from 1 to 25 wt.% between the different basins (Fig. 2). The organic enrichment observed within the Faraoni Level is therefore enhanced compared to the sediments above and below. The source of organic matter is mainly of phytoplanktonic origin, as indicated by the medium to high values of the hydrogen index (Fig. 2), as well as by detailed geochemical and palynological data [7–9,31].

A small positive excursion of is recorded in different Tethyan basins just around the Hauterivian/Barremian boundary (Fig. 3). Interpretations of carbon-isotope anomalies have sought to correlate positive carbon-isotope excursion with enhanced storage of organic carbon in marine environment [57,63,64], especially during the time of OAEs [5,45,56]. Following the same interpretation, the Latest Hauterivian–Early Barremian excursion recorded in different Tethyan basins suggests enhanced organic-carbon preservation at least at a regional scale. However, the Faraoni Level appears to coincide with a long-term minimum on the carbon-isotope curve, whereas the small positive excursion takes place immediately after. A comparable time-lag is known for OAE1a and the subsequent Early Aptian carbon-isotope positive excursion [13,50]. Anyway, this does not imply that the Faraoni Event is the cause of the Earliest Barremian carbon-isotope excursion, but that this time period experienced changes in the carbon cycle. Because the Faraoni Event appears in a very singular position in the general evolution of the carbon-isotope curve, further studies are needed to constrain the changes of the main factors that controlled the global carbon cycle around the Hauterivian–Barremian boundary.

4 Other possible records of the Faraoni Event

Additional records of the Faraoni Level were recently suggested in the Lombardian Basin [12], as wellas in northwestern Sicily [11]. The lithologic expression of the Faraoni Level of the Lombardian Basin is weak, although enrichment in organic carbon is obvious in the Upper Hauterivian strata [12]. For the Sicilian candidate, the organic content of this level is nil (pers. data). But this not necessary refute its correspondence to the Faraoni Event, as the eastern edge of the Trento Plateau records the Faraoni Level without any organic enrichment [7].

Although the drilling recovery is not complete, organic matter enrichments were recorded in the Atlantic Ocean in the Upper Hauterivian marly-limestone deposits of Moroccan (DSDP site 370) and Iberian margins (DSDP site 398). These black shales are also related to a minor positive carbon-isotope excursion [3,52].

The Upper Hauterivian marly succession of the North Sea borderlands (northern Germany) also records an interval of black shales within the Simbirskites discofalcatus ammonite zone [51], which is equivalent to the Tethyan Late Hauterivian Pseudothurmannia angulicostata zone.

In the central Pacific Ocean, the carbon-isotope curve registered around the boundary between Hauterivian and Barremian in the Resolution Guyot [42], shows a similar trend as those recorded in the Mediterranean Tethys (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that several laminated shales deposited in subtidal environments of this former atoll are enhanced in organic carbon [6].

5 Possible causes of the Faraoni Event

During the Mesozoic and Cainozoic, several major continental flood basalts and oceanic plateaux formed large igneous provinces that greatly influenced the climate and are associated with major biological crises [22]. It is usually admitted that Cretaceous OAEs were associated with this strong mantle dynamic leading to an increase in the flux of CO2 into the atmosphere, which may have produced warmer and more humid conditions [43,47,48]. The resulting greenhouse effect may have led to an intensified nutrient supply from continents to the ocean, and simultaneous thermohaline stratification of the water column.

According to available data, the peak of flooding in the Paranà–Etendeka continental basalt province is dated around 133 Ma [22,53,58] and ended around 131 Ma. Since trap emplacement was followed by continental break-up and formation of the South Atlantic Ocean, a tail of younger volcanism is expected. Indeed, rift-related dikes are dated in coastal Brazil beginning around 128 Ma [22] and a peak of submarine magma production of the Tristan da Cunha plume along the Rio Grande Rise correlates well with the CM5n magnetozone, around 127 Ma [32]. Hence, the deposition of the Faraoni Level seems to correlate with this supplement of oceanic magmatic activity that produced between 0.3 and 0.5 km3 of basalt per year (that correspond to for the duration of the Faraoni Event). This increase in crustal production may have created anoxic conditions in the ocean by driving one or more of the processes that led to higher fluxes of nutrients to surface waters and/or decrease in oxygen in oceanic waters [43,54].

However, another direct mechanism may also be inferred. OAEs are commonly related to first- or second-order transgressive phases [13,39]. Flooding of landmasses and creation of shelf seas may have enhanced productivity, in turn expanding the oxygen-minimum zone and drowning the carbonate platforms surrounding pelagic basins where dysoxia/anoxia were being developed [30,41]. Indeed, according to the Hardenbol et al. [35] eustatic chart, a major flooding surface (mfs Ha6) correlates precisely with the Pseudothurmannia catulloi ammonite subzone (Fig. 3). It is likely that this sea-level rise provoked and sustained enhanced productivity on shelf seas, and developed condensed intervals in offshore environments, leading to the accumulation of organic matter. In the same time a drowning of carbonate platform is recorded in the northern Tethyan carbonate platforms [30]. Because this sea-level rise is rapidly followed by a regressive trend and a sequence boundary in the final Hauterivian (Ha7 of Hardenbol et al. [35]), it could explain the lesser impact of the Faraoni Event on palaeobiological and geochemical proxies, as compared to other well-established anoxic events.

The above causes are not mutually exclusive. During period of high rate of ocean-crust production, current evidence suggests that OAEs were triggered by sea-level fluctuations [46].

6 Conclusion

Lithological, palaeontological and geochemical data reveal that numerous pelagic basins within the Mediterranean Tethys were prone to dysoxia/anoxia during the Latest Hauterivian, and recorded a short-lived anoxic event. The forcing mechanisms for this short-term event are likely to be similar as the ones responsible for global OAEs, such as high sea-level stand, volcanic activity, increasing productivity and an overall warm climate.