Version française abrégée

Introduction

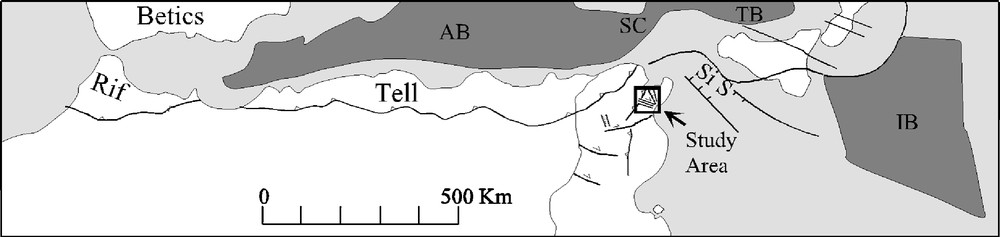

L’Atlas tunisien nord-oriental se situe à l’extrémité orientale de la Méditerranée occidentale, en bordure du détroit de Sicile (Fig. 1). La formation des structures affectant l’Atlas tunisien est associée à la dérive relative de l’Afrique par rapport à l’Eurasie. L’architecture finale de l’Atlas tunisien est liée aux activations et réactivations de plusieurs structures tectoniques pendant des phases tectoniques distensives et compressives [10,30].

Simplified map showing the position of the study area in western Mediterranean. AB: Algerian Basin; IB: Ionian Basin; SC: Sardinia Channel; SIS: Sicilian Strait; TB: Tyrrhenian Basin.

Fig. 1. Carte simplifiée montrant la position de la région d’étude en Méditerranée occidentale. AB : Bassin algérien ; IB : Bassin ionien ; SC : canal de Sardaigne ; SIS : détroit de Sicile ; TB : Bassin tyrrhénien.

Le mécanisme de la formation de l’Atlas tunisien, ainsi que des structures héritées qui ont contribué à l’obtention de la géométrie actuelle, a été expliqué par plusieurs modèles [2,4,6,9,27,28,31].

En utilisant des données de terrain, de sismique réflexion et de gravimétrie, on a montré l’existence, en Tunisie nord-orientale, de couloirs de décrochement orientés N120, ainsi que leur importance dans la genèse de l’Atlas nord-oriental.

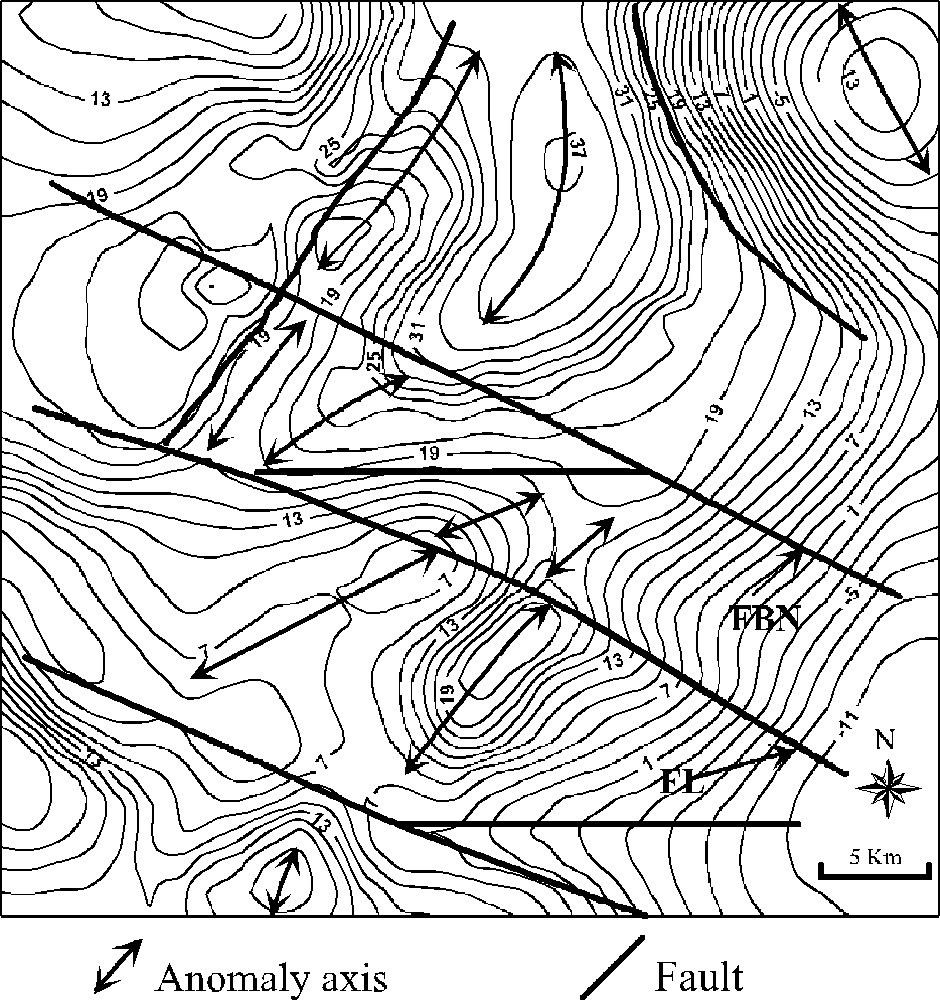

Étude structurale

L’analyse des nouvelles données gravimétriques obtenues de l’Office national des mines de Tunisie a permis la production de la carte gravimétrique de l’anomalie de Bouguer (Fig. 2). Au nord-est et au sud-est de cette carte, se présente une anomalie négative, dont l’amplitude minimale est de –13 mGal. Cette anomalie indique un déficit de masse, expliqué par le fossé de Grombalia [14]. Vers l’ouest, les anomalies deviennent positives, indiquant un excès de masse. Les variations observées sur la carte de l’anomalie de Bouguer indiquent des hétérogénéités structurales en subsurface, correspondant à des alignements majeurs orientés NE–SW, est–ouest, NW–SE et N120 (Fig. 2). Certaines portions de ces alignements coïncident avec des failles reconnues sur le terrain (Fig. 3), parmi lesquelles les failles N120 sont remarquables et forment des couloirs de décrochement. De part et d’autre de ces failles, la géométrie des déformations est différente d’un compartiment à un autre (Figs. 3 et 4).

Bouguer gravity map of Bouficha and Grombalia areas showing the NE–SW, east–west, NW–SE and N120 lineaments. FL: Lazirig Fault; FBN: Bou Naoura Fault.

Fig. 2. Carte gravimétrique de Bouguer des régions de Bouficha et de Grombalia, montrant les alignements NE–SW, est–ouest, NW–SE et N120. FL : Faille de Lazirig ; FBN : faille de Bou Naoura.

Geological map of Bouficha and Grombalia areas [11,16], modified. 1: Triassic; 2: Jurassic; 3: Early Cretaceous; 4: Albian–Cenomanian; 5: Late Cretaceous–Palaeocene; 6: Eocene; 7: Oligocene; 8: Miocene; 9: Plio-Quaternary. a: Seismic profiles; b: observed faults; c: faults deduced from gravity and seismicity data. FL: Lazirig Fault; FBN: Bou Naoura Fault.

Fig. 3. Carte géologique des régions de Bouficha et de Grombalia [11,16], modifié. 1 : Trias ; 2 : Jurassique ; 3 : Crétacé inférieur ; 4 : Albien–Cénomanien ; 5 : Crétacé supérieur–Paléocène ; 6 : Éocène ; 7 : Oligocène ; 8 : Miocène ; 9 : Plio-Quaternaire. a : Profils sismiques ; b : Failles observées ; c : Failles déduites à partir des données gravimétriques et sismiques. FL : Faille de Lazirig ; FBN : faille de Bou Naoura.

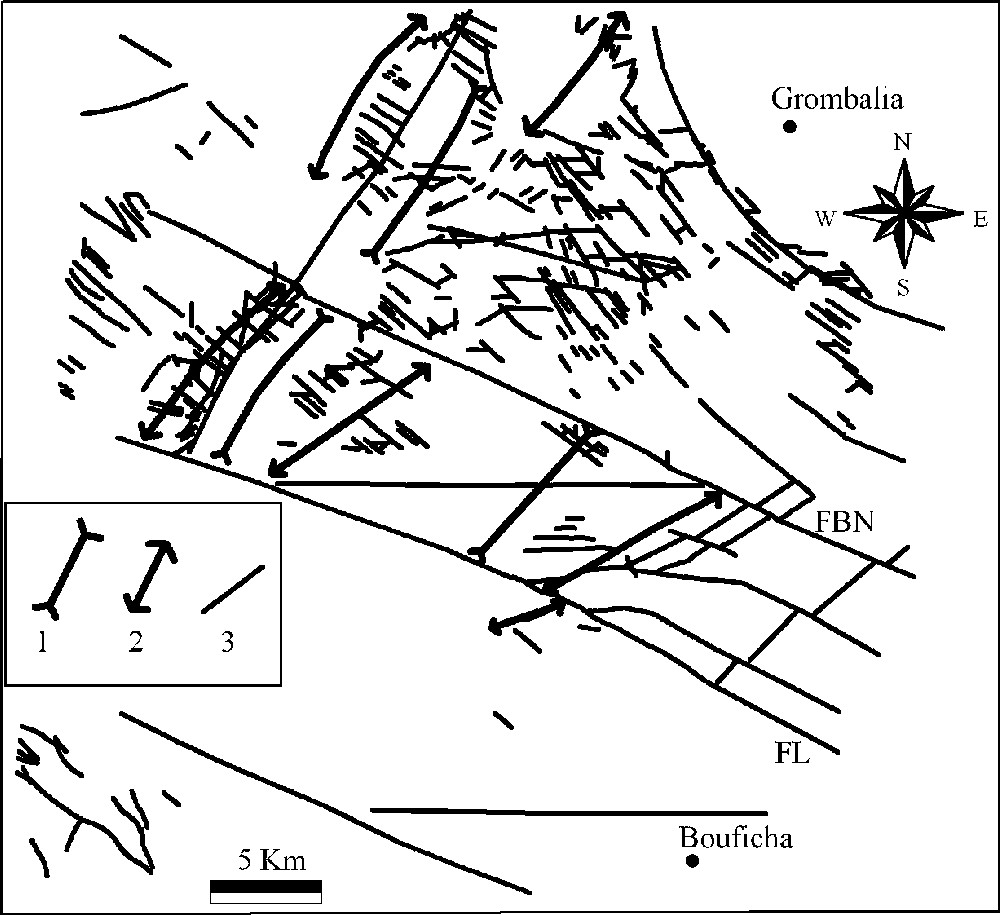

Structural map, showing the geometric variations from one compartment to another. 1: Syncline; 2: anticline; 3: fault; FL: Lazirig Fault; FBN: Bou Naoura Fault.

Fig. 4. Carte structurale montrant les variations géométriques d’un compartiment à un autre. 1 : Synclinal ; 2 : anticlinal ; 3 : faille ; FL : faille de Lazirig ; FBN : faille de Bou Naoura.

L’étude de trois lignes sismiques, orientées NE–SW, nous a permis de suivre ces décrochements en subsurface. Les failles de Lazirig (FL) et de Bou Naoura (FBN), de direction N120 (Fig. 3), montrent un pendage vers le nord et un jeu apparent à composante normale (Figs. 4 et 5) ; elles limitent d’autres failles de pendage vers le nord et vers le sud (Fig. 5), de direction est–ouest à N120.

Correlation of interpreted NE–SW seismic sections L1, L2 and L3 (location shown in Fig. 3), viewing deep structures. CS: Late Cretaceous; CI: Early Cretaceous; CP: Cretaceous–Palaeocene; E-Ma: Eocene–Aquitanian; MPLQ: Mio-Plio-Quaternary; TWT: Two-Wave Time.

Fig. 5. Corrélation des sections sismiques NE–SW interprétées L1, L2 et L3 (localisation sur la Fig. 3) montrant les structures en profondeur. CS : Crétacé supérieur ; CI : Crétacé inférieur ; CP : Crétacé–Paléocène ; E-Ma : Éocène–Aquitanien ; MPLQ : Mio-Plio-Quaternaire ; TWT : temps double.

Une différence de structuration est observée dans les profils L2 et L3, qui peut être due au fait qu’ils appartiennent à deux blocs différents, séparés par une faille de direction NE–SW, reconnue en subsurface [23].

Ces décrochements N120 ont été décrits aussi dans l’Atlas tunisien central et méridional [6,8,9,28–31].

Évolution tectonique

Le mouvement antihoraire de l’Apulie [1,20,32] peut être responsable de l’initiation et des réactivations des décrochements N120. Depuis le début du Crétacé supérieur jusqu’au Quaternaire inférieur, quatre phases tectoniques ont été mises en évidence [26].

Les variations géométriques des structures tectoniques de part et d’autre des failles de Lazirig et de Bou Naoura (Fig. 4) montrent que les couloirs de décrochement sont initiés avant le plissement et ont contribué aux variations sédimentaires d’un compartiment à un autre.

Au cours du Crétacé supérieur (Albien–Campanien inférieur), le régime tectonique en Tunisie est transtensif dextre, avec une extension ENE–WSW [7,25,31,32]. Pendant cette période, des décrochements N120 et des failles N160 sont initiés [32].

À la fin du Crétacé supérieur (Campanien supérieur–Maastrichtien), l’Afrique et l’Europe convergent [24], une phase compressive s’est produite en Tunisie [13,17,31], avec un axe de raccourcissement nord–sud [13]. Cette phase a continué jusqu’à l’Éocène supérieur [12,15,19,22,23], avec une contrainte σ1 orientée NW–SE à nord–sud [23]. Au cours de cette période, les failles N120 sont activées en décrochement dextre normal, les failles est–ouest le sont avec une composante normale, les failles NE–SW avec une composante inverse, tandis que les plis NE–SW sont ébauchés et la montée des séries triasiques est accentuée.

Au cours de la phase compressive Miocène supérieur, dont la contrainte σ1 est orientée N120 à N140 [23], les failles N120 sont réactivées en décrochement dextre normal. Associées à ces décrochements, d’autres failles sont activées avec une composante normale pour les directions NW–SE et est–ouest, et avec une composante inverse pour les directions NE–SW. Le plissement NE–SW est formé.

Au cours de la phase compressive Plio-Quaternaire inférieur, dont la contrainte σ1 est orientée NW–SE à nord–sud [3,7,8,18,23,28,31], les failles N120 ont joué en décrochement dextre inverse. Les failles associées sont remobilisées avec une composante normale pour les directions NW–SE et avec une composante inverse pour les directions est–ouest et NE–SW. Les plis de différentes directions ont été accentués.

Conclusion

En utilisant les données géologiques et géophysiques, on a constaté que la Tunisie nord-orientale était affectée par d’importantes failles orientées N120, formant des couloirs de décrochement. Ces failles limitent des compartiments dont la géométrie des déformations est différente d’un compartiment à un autre. Le contrôle structural exercé par les décrochements N120, depuis le Crétacé supérieur jusqu’au Plio-Quaternaire inférieur, a contribué à la génération de l’architecture actuelle de la Tunisie nord-orientale. Cependant, ces failles ont joué en décrochement dextre normal au cours du Crétacé supérieur, en décrochement dextre de la fin du Crétacé supérieur à l’Eocène supérieur, en décrochement dextre normal au cours du Miocène supérieur, et en décrochement dextre inverse au cours du Plio-Quaternaire inférieur. Associées à ces décrochements N120, d’autres failles héritées ont été réactivées et les mouvements halocinétiques accentués.

1 Introduction

The northeastern Tunisian Atlas is situated at the oriental extremity of the western Mediterranean region, i.e. the occidental border of the Sicilian Strait (Fig. 1). The main structures representing the Tunisian Atlas are the consequence of the relative drift of the African and Eurasian plates. The final architecture of the Tunisian Atlas is related to activations and reactivations of several tectonic structures during distensive and compressive tectonic phases [10,30].

Several models were assumed to explain the building mechanism of the Tunisian Atlas and the structures that contributed to obtain its current geometry [2,4,6,9,27,28,31].

In this paper, we have demonstrated the existence of N120 shear corridors in northeastern Tunisia and their importance on the generation of the northeastern Atlas, using field data, 2D seismic reflexion data obtained from the ‘Entreprise tunisienne des activités pétrolières’ (ETAP), and new gravity data collected in 2003 by the ‘Office national des mines de Tunisie’ (ONM).

2 Structural study

Northeastern Tunisia is characterized by Triassic to Quaternary sedimentary sequences outcrops. It is affected by NE–SW to NNE–SSW folds and by faults of various directions [5].

New gravity data in the Bouficha and Grombalia regions were analyzed. All the data were merged and reduced, using the 1967 International Gravity formula [21]. Free-air and Bouguer gravity corrections were made using sea level as a datum and 2.40 g cm–3 as a reduction density. Gravity data were gridded at 1-km spacing and contoured to produce a Bouguer gravity anomaly map (Fig. 2). This map shows, to the northeast and the southeast, negative gravity minima, whose amplitude is –13 mGal, which indicates a mass deficit associated with a subsidence. This negative anomaly is interpreted as a trough of Grombalia [14]. Anomalies become positive toward the west, which demonstrates a mass excess. The gravity maximum (+37 mGal) is located to the north. The gravity anomalies varieties shown in the Bouguer map indicate deep structure heterogeneities corresponding to significant NE–SW-, east–west-, NW–SE- and N120-trending lineaments (Fig. 2). Comparing these lineaments to the segments of faults recognised on the field (Fig. 3), we have distinguished that the N120 strike-slip faults are remarkable in that they form shear corridors. In both sides of these wrenches, the geometry of deformations is different; they are characterized by dissimilar fault and fold systems (Figs. 3 and 4):

- – the compartment situated to the south of the Lazirig Fault (FL) is characterised by the extent of Quaternary series outcrops and by reduced Meso-Cenozoic series outcrops. It is affected by a NE–SW folding (anticline) and by NW–SE-, east–west- and NE–SW-trending faults;

- – the compartment limited by the Lazirig Fault to the south and the Bou Naoura Fault (FBN) to the north is characterized by the outcrop of Mesozoic series to the northwest, Cenozoic series in the Centre, and Quaternary series to the southeast. It is affected by NE–SW folding (synclines and anticlines) and by faults with various directions;

- – the compartment situated to the north of the Bou Naoura Fault is more complicated, characterized by Meso-Cenozoic and Quaternary series outcrops and affected by NE–SW to NNE–SSW folding (synclines and anticlines) and by changed fault directions.

The investigation of NE–SW seismic profiles enables us to follow these shear corridors in subsurface. Three lines are used (L1, L2, and L3) (Fig. 5); they show the Lazirig and Bou Naoura faults. These N120-trending (Fig. 3) and dipping-toward-the-north faults present an apparent slip, with a normal component. They limit other faults, dipping toward the north and the south (Figs. 4 and 5), and trending east–west to N120.

Line L2 shows the thickness of the Eocene–Aquitanian Series toward the northeast, associated with a NW–SE fault with a normal component (Fig. 5). However, the thickness of this series observed in Line L3 is constant. This dissimilarity between the structures indicates that these lines are part of two different blocks, separated by a NE–SW subsurface fault [23] (Fig. 3).

N120-Trending wrenches were recognized in other regions of Tunisia, in the central and in the southern Atlas [6,8,9,28–31].

3 Tectonic evolution

Deformations affecting the northeastern Tunisian Atlas are tightly associated to African-Eurasian kinematics. The anti-clockwise movement of Apulia [1,20,32] may be responsible for the initiation of N120 strike-slip faults and for their reactivations. Since the beginning of the Late Cretaceous to the Early Quaternary, four tectonic phases took place in Tunisia [26].

The geometry variations of tectonic structures on both sides of the Lazirig and Bou Naoura Faults (Fig. 4) prove that the N120 shear corridors were initiated before folding and that they have contributed to sedimentary variations from a compartment to another:

- – during the beginning of the Late Cretaceous (Albian–Early Campanian), the tectonic mode in Tunisia is dextral transtensive, with ENE–WSW extension [7,25,31,32]. During this period, normal dextral N120 wrenches and normal N160 faults are initiated [32];

- – at the end of the Late Cretaceous (Late Campanian–Maastrichtian), Africa moved in convergence with Eurasia [24], a compressive phase occurred in Tunisia [13,17,31], with a north–south shortening axis [13]. This phase continued until the Late Eocene [12,15,19,22,23], with a σ1 constraint directed NW–SE to north–south [23]. During this period, the N120 wrenches have played with dextral normal strike-slip. East–west faults are activated with a normal component and NE–SW faults are activated with a reverse component. NE–SW folding is outlined and the rise of Triassic series is accentuated;

- – during the Late Miocene compressive phase, whose constraint σ1 is directed N120 to N140 [23], the N120 faults are reactivated in dextral normal strike-slip. Associated with these strike-slip faults, other faults are activated, with a normal component for the NW–SE and east–west directions and with reverse component for NE–SW directions. NE–SW folds are built.

During the Plio-Early Quaternary, a compressive phase, whose constraint σ1 is directed NW–SE to north–south [3,7,8,18,23,28,31], the N120 wrenches have played in dextral reverse strike-slip. Associated faults are remobilized with a normal component for the NW–SE directions and with a reverse component for the east–west and NE–SW directions. Most folds have been accentuated.

4 Conclusion

Using geological and geophysical data, we have demonstrated that northeastern Tunisia is affected by significant N120 faults forming shear corridors. These faults limit compartments with different deformation geometries. The structural control exerted by the N120 strike-slip faults since the Late Cretaceous to the Plio-Early Quaternary has contributed to the generation of northeastern Tunisia's current architecture. However, these wrenches have played in dextral normal strike-slip during the Late Cretaceous, in dextral strike-slip during the end of the Late Cretaceous to the Late Eocene, in dextral normal strike-slip during the Late Miocene, and in dextral reverse strike-slip during the Plio-Early Quaternary. Associated with these N120 wrenches, other inherited faults are reactivated and the halokinetic movements are accentuated. The synsedimentary tectonics has caused thickness variations of sediments, which have induced dissimilar deformations between compartments.