1 Introduction

The study of high-grade polydeformed metamorphic terrains is faced with important problems, as superimposed tectonic and thermal events lead to partial or complete transposition of early structures and metamorphic parageneses. Therefore, analysing the microstructure of deformed rocks becomes crucial to understand better the overprinting relations between different deformation phases and, consequently, the tectonic evolution of such terrains (e.g., [16]). As a part of microstructure studies, the analysis of quartz c-axis fabrics, which can be preserved in some cases, has proved to be a helpful tool and it has been widely used (e.g., [1,6,12,17]).

Quartz fabric geometry is related to the flow type and to the patterns and strength of the finite strain attained during progressive deformation. In coaxial progressive deformation, analysis of quartz c-axis fabrics allows discriminating between flattening, plane strain, and constriction [14,20,24]. In non-coaxial progressive deformation, quartz fabrics display a monoclinic symmetry (asymmetric fabrics) with respect to the reference frame defined by the XYZ-axes of the finite-strain ellipsoid. This external asymmetry has been traditionally used as a shear-sense indicator (e.g., [3,6,22]). Despite the common use of quartz crystallographic fabrics in metamorphic terrains, few researchers have focused this type of analysis on complex tectonic evolutions comprising both coaxial and non-coaxial strain paths. In these cases, the strain path can vary both in time (e.g., [6]) and space [12,17].

Some of the deformation phases that have superposed during the tectonic evolution of the Aracena metamorphic belt, southern Spain [2,5,8] were recorded by quartz c-axis fabrics in leucocratic gneisses. As presented in this paper, the analysis of these fabrics allows the discrimination between different tectonic phases. This microstructural analysis is relevant to decipher the kinematics of the main stages of the Variscan orogeny in the Aracena metamorphic belt. In particular, this work outlines the importance of the intra-orogenic extensional collapse event that has also been described in other regions of the European Variscan belt (e.g., [21]).

2 Geological setting and description of the studied samples

The Iberian Massif represents the largest and best exposed portion of the European Variscan orogen, which resulted from the convergence and subsequent collision between an Ibero-Armorican indentor and Laurussia (see [8,21] and references therein). In the southern branch of the Iberian Massif, the contact between the Ossa–Morena and the South Portuguese zones is marked by the high-temperature/low-pressure (HT/LP) Aracena metamorphic belt (Fig. 1a). Two main domains have been distinguished in the Aracena metamorphic belt [4]: an oceanic domain to the south and a continental domain to the north. Both domains present different stratigraphic sequences and record partly separated tectono-metamorphic evolutions [8]. The continental domain is composed of a variety of high- and medium-grade metamorphic rocks, including leucocratic gneisses, and different intermediate to basic intrusive rocks.

(a) Geological sketch of the southwestern Iberian massif with location of the Ossa-Morena zone (OMZ) and the South Portuguese zone (SPZ). CIZ is the Central Iberian zone. The inset shows the main massifs of the European Variscides and the marked area corresponds to the map of Fig. 1b. (b) Schematic geological map of the studied zone of the Aracena metamorphic belt (AMB) with location of the samples used in the study. Geographical and UTM coordinates are shown. The inset displays a lower hemisphere, equal-area projection of the mylonitic foliation (59 poles to S4, contouring after the Kamb method with expected values under uniform distribution equal to three times the standard deviation and contour interval of 2σ) and the stretching lineation L4 (dots), both related to the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone. (c) Schematic cross-section showing the overall structure of the southernmost area of the continental domain of the Aracena metamorphic belt, bounded by the Cortegana–Aguafría and Calabazares shear zones (modified after Díaz Azpiroz et al. [8]). Masquer

(a) Geological sketch of the southwestern Iberian massif with location of the Ossa-Morena zone (OMZ) and the South Portuguese zone (SPZ). CIZ is the Central Iberian zone. The inset shows the main massifs of the European Variscides and the marked ... Lire la suite

Fig. 1 (a) Schéma géologique du massif Ibérique sud-occidental avec la localisation de la zone Ossa-Morena (OMZ) et de la zone Sud-Portugaise (SPZ). CIZ est la zone Ibérique centrale. L’encart représente les principaux massifs européens varisques et le secteur indiqué correspond à la carte de la Fig. 1b. (b) Carte géologique schématique de la zone étudiée dans la ceinture métamorphique d’Aracena (AMB), avec localisation des échantillons utilisés dans cette étude. Les coordonnées géographiques et UTM sont indiquées. L’encart représente un hémisphère inférieur en projection équivalente de la foliation mylonitique (59 pôles en S4, tracé selon la méthode de Kamb, avec des valeurs attendues en distribution uniformes, égales à trois fois la déviation standard et l’équidistance entre courbes de 2σ) et de la linéation d’étirement L4 (points), les deux étant liées à la zone de cisaillement de Cortegana–Aguafría. (c) Coupe schématique montrant la structure d’ensemble du secteur le plus méridional du domaine continental de la ceinture métamorphique d’Aracena, limité par les zones de cisaillement de Cortegana–Aguafría et Calabazares. Masquer

Fig. 1 (a) Schéma géologique du massif Ibérique sud-occidental avec la localisation de la zone Ossa-Morena (OMZ) et de la zone Sud-Portugaise (SPZ). CIZ est la zone Ibérique centrale. L’encart représente les principaux massifs européens varisques et le secteur indiqué ... Lire la suite

The continental domain underwent, during Variscan plate convergence, a tectonic evolution that comprised up to four ductile deformation phases [8]. The first stage (D1) is related to kilometre-scale recumbent folds (e.g., [2]). However, these structures are not observed in the high-grade rocks of the Aracena metamorphic belt, where the S1 foliation is only preserved as relic hinges within some S2 foliation microlithons [8]. The second tectonic phase (D2) is associated with a widespread extensional event (see below and also [8]). A penetrative metamorphic foliation (S2me) is present throughout the continental domain, whereas at shear zones, a localised mylonitic foliation (S2my) and a stretching lineation (L2) developed. This deformation phase was accompanied by a high-temperature/low-pressure (HT/LP) metamorphism [4,8]. The third stage (D3) generated symmetric upright folds with variable fold axial trace orientations. The last ductile deformation event (D4) gave place to kilometre-scale, southwest-verging antiforms, and related reverse shear zones (see below, Fig. 1c and also [8]). Both structures share a NW–SE direction. A penetrative mylonitic foliation (S4) with a NW–SE trend and nearly down-dip stretching lineations (L4) developed within these shear zones (Fig. 1b).

The limit between the high-grade and the medium-grade sectors of the Aracena metamorphic belt (Fig. 1b and c) is a high-strain zone, the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone. The tectonic evolution of the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone is marked by the presence of kinematic indicators of both normal and reverse shear senses (see below and also [5]). This contribution focuses on the quartz c-axis fabrics of the leucocratic gneisses deformed by the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone.

The leucocratic gneisses are either granitic (Qtz–Kfs–Pl) or trondhjemitic (Qtz–Pl) in composition. Both types contain minor amounts of biotite, clinoamphibole, and/or clinopyroxene. Occasionally, garnet, epidote, or graphite may be present. The microstructure of the leucocratic gneiss localised in the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone is essentially the same, irrespective of the dominant deformation phase (D2 or D4) or the flow-type recorded by the quartz fabric. This microstructure is characterised by quartz polycrystalline ribbons defining the stretching lineation, which are surrounded by a fine-grained quartz-feldspathic matrix (Fig. 2a). Quartz grains are irregular in shape, rather elongated, with numerous grain and subgrain boundaries, as well as some deformation bands (Fig. 2a). These microstructures suggest the activity of subgrain rotation recrystallization (e.g., [10,19,23]). However, bulging and pinning structures, typical of grain boundary migration recrystallization [10,11], have been recognised as well (Fig. 2b), suggesting that metamorphic conditions during deformation (D2 and/or D4) reached, at least, the lower-amphibolite facies (e.g., [23]). Both the ribbons and the matrix quartz grains display a well-developed lattice preferred orientation (LPO), indicating that dislocation creep has been active during quartz deformation (see [19]).

Photographs of structures related to the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone. (a) Mylonitic foliation (S4) of leucocratic gneisses defined by quartz ribbons. Dynamic recrystallization textures (subgrain boundaries and irregular grain boundaries) are observed both in the ribbons and the matrix. (b) Grain-boundary migration recrystallization textures in leucocratic gneisses. Bulging (B) and pinning (P) examples are marked with arrows. (c) Leucocratic gneisses from the Cortegana cross-section showing asymmetric minor folds (arrow) related to the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone (outcrop located near sample CO-6, see Fig. 1b) that indicate a top-to-the-south shear sense. (d) Amphibolites of the Aguafría sector (outcropping near sample AG-6) showing asymmetric minor folds indicating a top-to-the-north shear sense. Masquer

Photographs of structures related to the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone. (a) Mylonitic foliation (S4) of leucocratic gneisses defined by quartz ribbons. Dynamic recrystallization textures (subgrain boundaries and irregular grain boundaries) are observed both in the ribbons and the matrix. (b) Grain-boundary ... Lire la suite

Fig. 2 Photographies de structures liées à la zone de cisaillement de Cortegana–Aguafría. (a) Foliation mylonitique (S4) de gneiss leucocrates, définie par des rubans de quartz. Des textures de recristallisation dynamique (limites subgranulaires et limites irrégulières entre grains) sont observées à la fois dans les rubans et dans la matrice. (b) Texture de recristallisation par migration à la frontière de grains dans les gneiss leucocrates. Les exemples de renflement (B) et de raccord (P) sont indiqués par des flèches. (c) Gneiss leucocrates de la coupe de Cortegana, montrant des plis mineurs asymétriques (flèche), en liaison avec la zone de cisaillement Cortegana–Aguafría (affleurement situé près de l’échantillon CO-6, voir Fig. 1b), qui indique un sens de cisaillement avec « top » vers le sud. (d) Amphibolites du secteur d’Aguafría (affleurement près de l’échantillon AG-6) qui montrent des plis mineurs asymétriques indiquant un sens de cisaillement avec « top » vers le nord. Masquer

Fig. 2 Photographies de structures liées à la zone de cisaillement de Cortegana–Aguafría. (a) Foliation mylonitique (S4) de gneiss leucocrates, définie par des rubans de quartz. Des textures de recristallisation dynamique (limites subgranulaires et limites irrégulières entre grains) sont observées ... Lire la suite

3 Quartz c-axis fabrics

3.1 Methodology

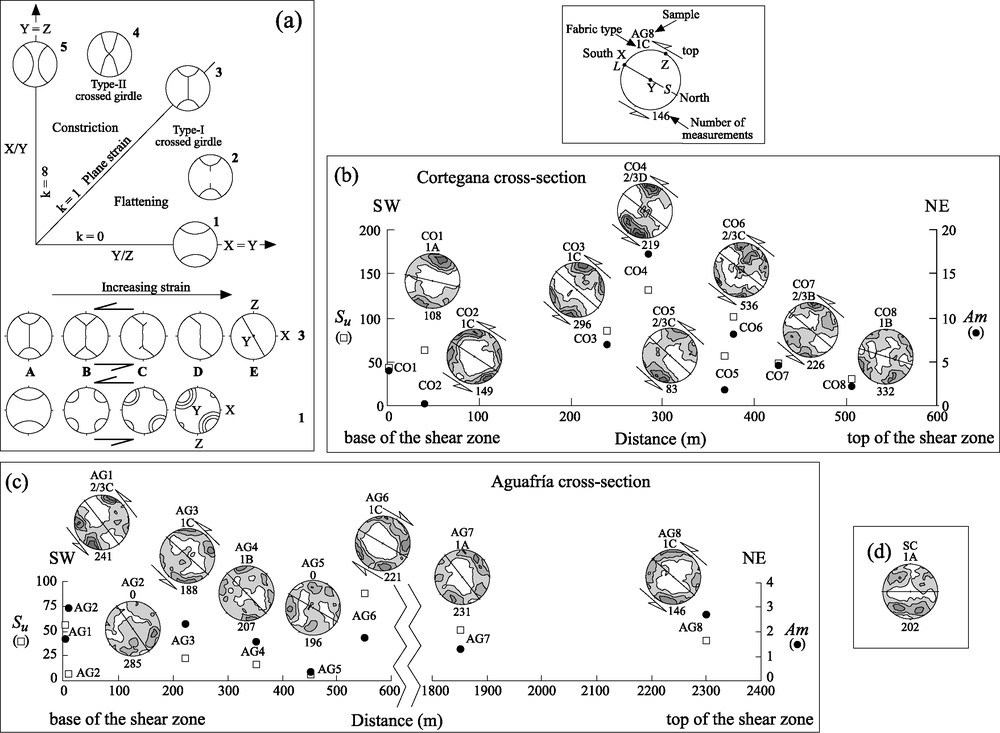

Quartz c-axis fabrics have been measured in the leucocratic gneisses of the Aracena metamorphic belt to estimate qualitatively the amount of strain and to deduce shear senses. Quartz c-axes have been measured in the XZ section (X being parallel to the dominant stretching lineation in each sample, which can be either L2 or L4) of seventeen samples using a four-axis universal stage, according to Turner and Weiss’ method [25]. The obtained data were represented in equal-area, lower hemisphere pole-figure projections. Sixteen samples correspond to two cross-sections normal to the main trend of the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone (Fig. 1b). These are the Cortegana cross-section (samples CO1 to CO8), and the Aguafría cross-section (samples AG1 to AG8). Sample SC corresponds to a minor shear zone located in the high-grade area of the continental domain (Fig. 1b). The quartz fabrics have been classified using an extended Flinn diagram (Fig. 3).

(a) Idealized skeletal quartz c-axis fabric diagrams. Classifications of c-axis fabric diagrams based on the shape parameter of the strain ellipsoid (k) is shown on a Flinn diagram [14]. The variation of c-axis fabrics due to increasing strain of a rotational plane deformation (based on Schmid and Casey [20]) and the variation of c-axis fabrics as a consequence of the increasing influence of a non-coaxial component of deformation coeval or later with respect to a flattening deformation (modified after Dell’ Angelo and Tullis, [7]) are also shown. In the latter, small circles of c-axes develop around the Z-axis of the finite strain ellipsoid due to the flattening component. These small circles are progressively modified into two unequally populated maxima as the influence of the non-coaxial component of deformation increases. The asymmetry of these fabrics can be used as kinematic criterion. The resulting fabric type is identified by a number corresponding to the position in the Flinn diagram and a letter corresponding to the relative amount of non-coaxial deformation. (b), (c) Variation with distance to the structural base of the Cortegana-Aguafria shear zone (located at the origin) of the statistical functions Su [15] (white squares) and Am [9] (black circles) of the quartz c-axis fabrics measured in leucocratic gneisses, at the (b) Cortegana and (c) Aguafria cross-sections. Distances are measured normal to the trend of the shear zone (note that vertical and horizontal scales are different in both diagrams). Quartz c-axis are shown in lower hemisphere, equal-area projections, with contouring after the Kamb method with E (number of poles expected at each counting circle under uniform distribution) equal to three times the standard deviation and contour interval of 2σ. The fabrics are classified according to the types presented in (a). Inset shows the location of the X, Y and Z-axes of the finite strain ellipsoid, the structural top and the geographical South. S and L correspond to the dominant foliation (S2 and S4) and lineation (L2 or L4) respectively. Sample reference, fabric type and number or measurements are also displayed in each sample as in the inset. When possible, the apparent shear sense interpreted from the external asymmetry of the quartz fabrics is indicated. (d) Quartz c-axis fabrics of leucocratic gneisses from a minor shear zone in the high-grade domain (sample SC). Same conventions as in (b) and (c). Masquer

(a) Idealized skeletal quartz c-axis fabric diagrams. Classifications of c-axis fabric diagrams based on the shape parameter of the strain ellipsoid (k) is shown on a Flinn diagram [14]. The variation of c-axis fabrics due to ... Lire la suite

Fig. 3 (a) Diagrammes idéalisés d’orientation de fabrique selon l’axe c de squelettes de quartz. La classification de ces diagrammes, basée sur le paramètre de forme de l’ellipsoïde des déformations (k), est représentée sur un diagramme Flinn [14]. La variation de l’orientation de fabrique selon l’axe c due à la contrainte croissante de la déformation rotationnelle dans le plan (basée sur Schmid et Casey, [20]) et la variation de fabrique selon l’axe c, en tant que conséquence de l’influence croissante d’une composante non coaxiale de déformation contemporaine ou tardive par rapport à la déformation d’aplatissement (modifié selon Dell Angelo et Tullis [7]) sont aussi présentées. Dans ce dernier cas, de petits cercles d’axe c se développent autour de l’axe Z de l’ellipsoïde des déformations finies, en raison de la composante d’aplatissement. Les petits cercles sont progressivement modifiés en deux maxima inégalement fournis, lorsque l’influence de la composante non coaxiale de la déformation augmente. L’asymétrie de ces fabriques peut être utilisée comme critère cinématique. Le type de fabrique qui en résulte est identifié par un nombre, qui correspond à la position sur le diagramme de Flinn et une lettre correspondant à la proportion relative de déformation non coaxiale. (b,c) Variation avec la distance à la structure basale de la zone de cisaillement de Cortegana–Aguafría (localisation d’origine), des fonctions statistiques Su [15] (carrés blancs) et Am [9] (cercles noirs) des fabriques selon l’axe c mesurées dans les gneiss leucocrates des coupes Cortegana (b) et Aguafría (c). Les distances sont mesurées perpendiculairement à la direction de la zone de cisaillement (à noter que les échelles verticales et horizontales sont différentes dans les deux types de diagramme). Les axes c de quartz sont présentés dans l’hémisphère inférieur, en projection équivalente, avec tracé selon la méthode de Kamb (E est le nombre de pôles attendus à chaque cercle tracé en distribution uniforme), égaux à trois fois la déviation standard et l’intervalle entre courbes de 2σ. Les orientations de fabrique sont classées selon les types présentés (en a). L’encart montre la localisation des axes X, Y, Z de l’ellipsoïde des déformations finies, du « top » structural et du Sud géographique. S et L correspondent respectivement à la foliation dominante (S2 ou S4) et à la linéation dominante (L2 ou L4). La référence de l’échantillon, le type d’orientation et le nombre de mesures sont aussi fournis pour chaque échantillon, comme dans l’encart. Quand c’est possible, le sens de cisaillement apparent, interprété à partir de l’asymétrie externe de la fabrique du quartz, est indiqué. (d) Fabrique selon l’axe c du quartz de gneiss leucocrates à partir d’une zone de cisaillement mineur dans le domaine de métamorphisme de haut degré (échantillon SC). Mêmes conventions qu’en (b) et (c). Masquer

Fig. 3 (a) Diagrammes idéalisés d’orientation de fabrique selon l’axe c de squelettes de quartz. La classification de ces diagrammes, basée sur le paramètre de forme de l’ellipsoïde des déformations (k), est représentée sur un diagramme Flinn Lire la suite

Measurement of randomness (isotropy) of crystallographic fabrics can be done with confidence in quartz c-axis fabrics [9]; deviation from isotropy is measured with the parameter Su [13,15], which is defined as:

| (1) |

Tectonic evolution recorded by quartz c-axis fabrics of leucocratic gneisses of the Aracena metamorphic belt. Diagrams are not to scale. Schematic diagrams of the observed types of quartz c-axis fabrics (S: foliation plane) as well as approximate strain ellipsoid sections are shown. (a) Foliation before the onset of D2. (b) Fabrics generated (including boudinage structures) during D2, which consisted in flattening and localised simple shear zones with top-to-the-north shear-sense. S2me: metamorphic foliation, S2my: mylonitic foliation. (c) Fabrics developed due to the local superposition of D4 (reverse, top-to-the-south shear zones) over D2. Masquer

Tectonic evolution recorded by quartz c-axis fabrics of leucocratic gneisses of the Aracena metamorphic belt. Diagrams are not to scale. Schematic diagrams of the observed types of quartz c-axis fabrics (S: foliation plane) as well as approximate strain ... Lire la suite

Fig. 4 Évolution tectonique enregistrée par la fabrique selon l’axe c du quartz des gneiss leucocrates de la ceinture métamorphique d’Aracena. Les diagrammes ne sont pas à l’échelle. Les diagrammes schématiques des différents types de fabriques selon l’axe c du quartz observés (S : plan de foliation), ainsi que des sections approximatives de l’ellipsoïde des déformations sont présentés. (a) Foliation avant la mise en place de D2. (b) Fabrique générée (incluant les structures de boudinage) pendant D2, qui consiste en un aplatissement et des zones de cisaillement localisé, avec un sens de cisaillement avec « top » dirigé vers le nord. S2me : foliation métamorphique, S2my : foliation mylonitique. Fabrique développée par superposition locale de D4 (zones de cisaillement inverses, avec « top » dirigés vers le sud) sur D2. Masquer

Fig. 4 Évolution tectonique enregistrée par la fabrique selon l’axe c du quartz des gneiss leucocrates de la ceinture métamorphique d’Aracena. Les diagrammes ne sont pas à l’échelle. Les diagrammes schématiques des différents types de fabriques selon l’axe Lire la suite

4 Results

Our quartz c-axis fabrics may be divided into three main types (Fig. 3). Type 0 is weak or random (AG2 and AG5), suggesting low amounts of strain and/or static recrystallization. Type 1 shows symmetric small circles around the maximum shortening direction of the finite strain ellipsoid (Z) with few c-axes plotting parallel to the intermediate axis (Y); the fabric skeleton is symmetrical with respect to the foliation plane, whereas the distribution of the c-axes within the small circles can be either symmetrical (subtype-1A, samples CO1, AG7 and SC) or asymmetrical (types 1B and 1C, samples CO2, CO3, AG3, AG6 and AG8) with respect to the finite-strain axes. Type 2/3 is asymmetric type-I crossed girdles (CO4 to CO7 and AG1). See Fig. 3b for a definition of type-I crossed girdles.

Focusing on the two studied cross-sections, Cortegana and Aguafría, the quartz fabrics, as well as their Su and Am statistical functions, exhibit significant differences (Fig. 4).

- (1) The two samples, located at the edges of the Cortegana cross-section (CO1 and CO8) show weak fabrics that, presumably, reflect low amounts of strain. Both show a high external symmetry, as evidenced by low Am values. Sample CO4 represents the strongest and the most asymmetric fabric (highest Su and Am values). The rest of the diagrams show intermediate strengths and asymmetries. The samples located to the southwest of CO4 (CO2 and CO3) display small-circles around the Z-direction, suggesting a top-to-the-south sense of movement. Samples CO4 to 7 show an asymmetric type-I crossed girdles indicating a top-to-the-south sense of movement (Fig. 4a).

- (2) The Aguafría fabrics are diverse, although, in general, their strength and asymmetry are lower than those of the Cortegana cross-section are (Fig. 4b). Fabrics AG2 and AG5 are nearly random. Fabrics AG3, AG4, AG6, AG7, and AG8 tend to small circles around the Z-direction. AG4 and AG7 exhibit statistical external symmetries, whereas AG3, AG6 and AG8 are asymmetrical and display opposed shear senses (top-to-the-south for AG3 and AG8, and top-to-the-north for AG6). Finally, fabric AG1 defines an asymmetric type-I crossed girdle, compatible with a top-to-the-south sense of movement.

5 Discussion

Quartz c-axis fabric analysis of leucocratic gneisses from the continental domain of the Aracena metamorphic belt supports a complex tectonic evolution for this sector of the Iberian Massif. These fabrics could record the superposition of two different tectonic phases involving flattening and non-coaxial plane strain (Fig. 4). In both stages, discrete shear zones were generated, with an associated mylonitic foliation and a stretching lineation defined by polycrystalline quartz ribbons formed by dynamic recrystallization. The following interpretation takes into account the geological evolution of the Aracena metamorphic belt [8].

Type-2/3 fabrics (i.e., CO4 to CO7 and AG-1) probably resulted from a non-coaxial plane strain (see [14]). These fabrics invariably indicate a top-to-the-south sense of movement, in accordance with other kinematic criteria (Fig. 2c). In such cases, the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone is interpreted as a reverse, southwest-verging shear zone that correlates with several thrust structures reported elsewhere in the continental domain, like other reverse shear zones and southwest-verging folds [5,8]. Consequently, all of these structures can be attributed to the D4 tectonic phase.

Type-1 fabrics are consistent with flattening [20]. Other structures related to flattening in the continental domain are chocolate-tablet boudinage structures developed in marbles [8]. The boudinage structures and the structures of samples showing type-1 fabrics (mylonitic foliation and stretching lineation) were folded during D3 [8] and, consequently, may be assigned to a previous deformation phase, D2. Some of these flattening fabrics are symmetrical (CO1, AG4, AG7, and SC); the others are asymmetrical (Fig. 3a), suggesting the influence of a non-coaxial flow component (e.g., [14,20,24]). Asymmetric flattening fabrics (CO2, CO3, AG3, AG6 and AG8) are similar to those generated experimentally in quartzites deformed by a combination of axial compression (ɛ > 30%) and simple shear (γ > 2) (see Fig. 4d–e of Dell’Angelo and Tullis [7]) since both show a high concentration of c-axes close to the foliation pole with an asymmetric distribution on sides of it. These fabrics point to either normal (AG6) or reverse (CO2, CO3, AG3, and AG8) senses of displacement. Several structures (Fig. 2d) indicating also a normal, top-to-the-north sense of movement have been observed near sample AG6, whose fabric could be due to discrete normal shear zones related to vertical flattening. Asymmetric type-I crossed girdles indicating a normal displacement are absent, suggesting that simple-shearing with a normal sense of displacement in the continental domain was always coeval with a component of flattening. Presence of such fabrics throughout the continental domain of the Aracena metamorphic belt [5,8] suggests that flattening was ubiquitous, the extensional non-coaxial deformation remaining concentrated in discrete shear zones (Fig. 4b). Similar fabrics generated because of such a strain partitioning have been described in Sierra Alamilla, Spain [17], and in the Moine thrust, Scotland [12]. The combination of vertical flattening coeval with displacement along localised normal shear zones strongly suggests that extensional collapse or gravity spreading took place to the north of the continental domain of the Aracena metamorphic belt. This event took place during the D2 phase in association with the HT/LP metamorphic event [4,8]; it can be correlated with a general episode of extension that occurred throughout the southern branch of the Iberian Massif (e.g., [21]).

Assuming that a fabric that forms during flattening can strongly influence the development of subsequent fabrics [14,26], we infer that, in the present case, the fabrics that show combinations of flattening and reverse sense of displacement (CO2, CO3, AG3 and AG8) indicate the superimposition of two tectonic phases: flattening during D2 and reverse shearing during D4, which lead to reactivation of discrete shear zones formed during D2 (Fig. 4c). One of the most important of these shear zones is the Cortegana–Aguafría shear zone, localised at the boundary between the high-grade and the medium-grade zones of the continental domain (Fig. 1b). In areas where deformation produced during D4 was very intense (such as in the Cortegana sector), the fabrics formed during D2 were erased and asymmetric type-I crossed girdles developed. As we move away from these highly deformed bands, the asymmetry of the quartz fabrics becomes progressively weaker. In weakly deformed areas (such as in the Aguafría sector), the original D2 fabric is partly preserved and a weak asymmetry occasionally developed because of D4. Finally, in areas not affected by D4, the original D2 fabric remains unchanged (Fig. 4c). A similar tectonic evolution based on the changes displayed by quartz fabrics has been proposed for the Adra nappe in the Betic Chain [6].

6 Conclusions

Our quartz fabrics suggest that the tectonic evolution of leucocratic gneisses from the Aracena metamorphic belt comprises two major deformation events: (1) an extensional phase that generated vertical flattening and normal shear zones, and (2) and an episode of shortening giving place to reverse shear zones. Our data support the Variscan tectonic evolution scheme proposed for the contact between the Ossa–Morena and the South Portuguese zones [8], and, more generally, for the southern branch of the Iberian Massif (e.g., [21]), according to which a widespread extensional event was followed by a transpressive one that resulted in southwest-vergent shortening structures coeval with strike-slip and poorly partitioned transpressional deformation zones.

The analysed quartz fabrics have recorded the last deformation event that affected the leucocratic gneisses and, in some cases, part of their deformation path, which includes also a previous phase. As a conclusion of this study, we propose that the superimposition of a non-coaxial strain event over a flattening stage can generate quartz c-axis fabrics where small circles around the Z-axis of the finite-strain ellipsoid are associated with an asymmetric distribution of c-axes within the small circles. This external asymmetry can be used as a kinematic criterion for the last deformation event.

7 Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the BTE-2001-2769, BTE2003-0557-CO2-02, CGL2004-06808-CO4-02/BTE and CGL2006-08639/BTE projects (Spanish Ministry of Education and Science), the Junta de Andalucía (groups RNM-120 and RNM-316) and Huelva University. Thanks to G. Lloyd and M. Casey for useful discussions. Careful reviews by Jacques Angelier and an anonymous reviewer are gratefully acknowledged.