In a recent article, Simancas et al., 2009 take up again (see also El Hadi et al., 2006b; Simancas et al., 2005) an exciting problem, which concerns the former relationships between the Iberian and Moroccan Variscides. This issue has been seldom approached up to now from a geodynamic point of view [e.g. Michard and Piqué, 1980; Bordonaro et al., 1979; Piqué et al., 1991]. Restoring these relationships is hampered by the large dextral wrench-faults that crosscut the Variscan belt from Latest Carboniferous to Permian (Bard, 1997), and by the subsequent Mesozoic-Cenozoic displacements of Africa vs Europe. However, it is certainly worthy to tackle this issue as the Moroccan Variscides are the only large and well-exposed segment of the Variscan Belt Southern Branch (Guillot and Menot, 2009) that preserved its original relationships with Gondwana. We are grateful to Simancas et al., 2005; Simancas et al., 2009 for their repeated efforts to tackle this major geodynamic problem in the most general framework of the Variscan plate tectonics. In the present comment, we do not intend to question the latter framework, i.e. the position of the suture(s) and orientation of the subduction zone(s), but simply to address the brief account of the Moroccan Variscides that is proposed by our colleagues, and that they use to restore the connection of this Variscan segment with that of South Iberia.

Briefly, Simancas et al., 2009 tend to minimize the pre-orogenic and syn-orogenic separation between the Anti-Atlas Domain, which clearly represents the weakly deformed border of the West African Craton [e.g. Hoepffner et al., 2005; Soulaimani and Burkhard, 2008], and the strongly deformed Meseta Domain, which displays clear evidence of crustal shortening and orogenic magmatism [e.g. Hoepffner et al., 2006; Michard et al., 2008]. In their Fig. 5 (Present state) and Fig. 6C-D (Late Carboniferous), the boundary between these domains is labelled “South Atlas Fault” (SAF). In Fig. 6A-B, it is assumed that the “SAF” did not exist during the Early Carboniferous. They “believe inconsistent the […] interpretations giving to the SAF the category of a major Paleozoic continental fault accommodating the whole shortening of the Moroccan Variscides”. We cannot agree with such a view of the Meseta – Anti-Atlas relationships for the reasons summarized hereafter (see Michard et al., 2008 for more details):

- 1-. It is important to emphasize significant differences between the Meseta and the Anti-Atlas domains (Michard and Piqué, 1980; Michard et al., 1989; Hoepffner et al., 2005). The whole Meseta Domain is characterised by:

- (i) much more important shortening than the Anti-Atlas; synkinematic metamorphism reaching frequently the amphibolite facies;

- (ii) emplacement of Variscan granitoids, which are lacking in the Anti-Atlas;

- (iii) dominantly north-westward structural vergence contrasting with the south-eastward to southward vergence of Anti-Atlas. These fundamental differences between the two major domains of the Moroccan Variscides call for a basic role of the South Meseta Zone as a major Variscan lithospheric discontinuity – not a mere Late Carboniferous strike-slip fault.

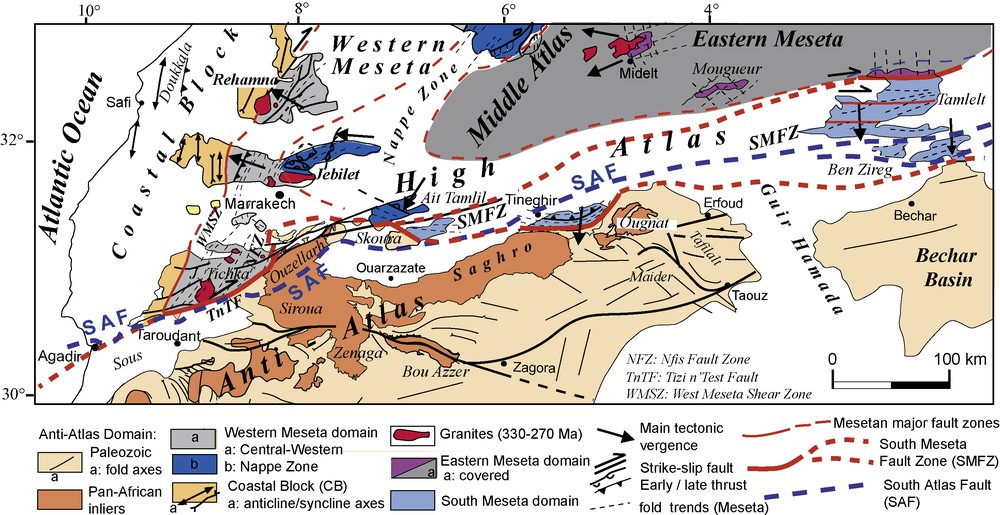

- 2-. We think that calling “South Atlasic Fault (SAF)” the southern boundary of the Meseta Domain is misleading. In fact, the “Faille (Accident) sud-atlasique” is defined since years (Ambroggi and Neltner, 1952; Russo and Russo, 1934) as the system of faults that bound the Mesozoic-Cenozoic Atlas Belt to the south. The SAF extends roughly east-west over 1700 km from Agadir in Morocco to Gabès in Tunisia e.g. Frizon de Lamotte et al., 2000; Frizon de Lamotte et al., 2008. At the scale of North Africa, the southeastern boundary of the Meseta Domain and the southeastern front of the Variscan deformation in the foreland trend ENE, oblique to the SAF, and the Atlas basement of eastern Algeria and Tunisia only shows wide wavelength Paleozoic structures (Bracène, 2002; Mejri et al., 2009). The Moroccan outcrops also allow us to distinguish between the Mesozoic-Cenozoic SAF and the Meseta Domain south boundary (Fig. 1). This boundary was recognized by Mattauer et al., 1972 and Proust et al., 1977 in the western High Atlas as being an important dextral wrench fault (Tizi n’Test Fault). Then, Michard et al., 1989 and Piqué and Michard, 1989 argued that this boundary has to continue to eastern Morocco since the deformation of eastern Meseta strongly contrasts with that of eastern Anti-Atlas, and coined the term of “Atlas Paleozoic Transform Fault” (APTZ). It must be stressed that this name does not refer to any sutured oceanic ridge, but to the transformation of shortening (Eastern and Western Meseta) into displacement (wrenching) at the southern boundary of the Meseta Domain, against the poorly deformed Anti-Atlas. APTZ and SAF are obviously not coincident in the Marrakech High Atlas, as the basement of its western part belongs to the Meseta Domain whereas that of its eastern part belongs to the Anti-Atlas Domain (Ouzellarh Promontory, (Choubert, 1952). West of the Ouzellarh Massif, Ouanaimi and Petit, 1992 demonstrated that the APTZ trends roughly NNE (Nfis Fault), being crosscut by several Atlas faults (Meltsen, etc.). East of the Ouzellarh Massif, the southern boundary of the Meseta Domain splits into a fault bundle defining a wide zone. The southernmost fault trends ESE across the Skoura Paleozoic inlier of the High Atlas (Laville, 1980), whereas the northernmost can be followed between the Skoura and Ait Tamlil inlier (Jenny et al., 1989). The southern fault connects further east with the front of the Tineghir Paleozoic slivers thrust onto the Anti-Atlas (Michard et al., 1982; Schiavo et al., 2007; Dal Piaz et al., 2007). There, the front of the Mesetan thrust units is located 50 km south of the SAF. Still further east, the Meseta Domain is separated from the Anti-Atlas by a tectonic zone cropping out within the High Atlas (Tamlelt inlier) and south of it (Ben Zireg area). In this “South Meseta Zone”, Houari and Hoepffner, 2003 observed both dextral strike-slip (particularly to the north of the Tamlelt) and south-vergent reverse faulting;

- 3-. Let us call in the following “South Meseta Fault Zone” (SMFZ; Fig. 2A) the boundary zone (either narrow or wide, west and east of the Ouzellarh salient, respectively) between the Mesetan Variscides and the Anti-Atlas. Notice that this major Paleozoic lineament was also referred to as “South Meseta Shear Zone” (Piqué et al., 1991). Contrary to Simancas et al., 2009, we argue that a precursor of the SMFZ occurred as early as the Late Devonian-Early Carboniferous as synmetamorphic Variscan folding occurred then in the Eastern Meseta and eastern Western Meseta (Hoepffner et al., 2005; Hoepffner et al., 2006; Michard et al., 2008; Piqué and Michard, 1989) whereas extension prevailed in the Anti-Atlas (Baidder et al., 2008; Michard et al., 2008; Wendt, 1985). As the Late Devonian-Early Carboniferous folds of Eastern Meseta are synmetamorphic recumbent/overturned folds (Hoepffner et al., 2006; Michard et al., 2008, Fig. 3.25A), the “proto-SFMZ” cannot simply represent a (sinistral) strike-slip fault (as proposed by Piqué and Michard, 1989). Consistently, a striking contrast characterizes the Lower Carboniferous deposits of the Anti-Atlas shelf and Meseta turbiditic basins, respectively (see Michard et al., 2008 with references therein). Moreover, we feel critical not to exaggerate the role of strike-slip tectonics along the SMFZ during the Carboniferous, and in contrast we emphasize that of compression, which is well illustrated in the Tineghir, Tisdafine and Ben Zireg thrust contacts (Houari and Hoepffner, 2003; Michard et al., 1982; Soualhine et al., 2003) and the Anti-Atlas itself (Tata area (Soulaimani and Burkhard, 2008); Ougnat, (Raddi et al., 2007)). During the Late Carboniferous, i.e. when the Meseta and Anti-Atlas domains were colliding, the occurrence of the Ouzellarh salient limited necessarily the importance of strike-slip displacements. We have to admit that Eastern Meseta was structurally independent from the Anti-Atlas at that time. Moreover, such independence also occurred between the Western Meseta and Anti-Atlas as Western and Eastern Meseta were connected through the Nappe Zone during the Carboniferous (Ben Abbou et al., 2001; Bouabdelli and Piqué, 1996);

- 4-. Looking farther in the past, the SMFZ appears as an ancient domain of thinned crust formed during the Lower Paleozoic. This is suggested by varied stratigraphic data from the eastern and western transects:

- (i) the Cambrian-Lower Ordovician isopachs (Boudda et al., 1979; Choubert, 1952; Destombes, 2006a; Destombes, 2006b) suggest the occurrence of a rift shoulder system from the Saghro-Ougnat to SW Anti-Atlas (cf. Michard et al., 2008, Fig. 3.6);

- (ii) Late Ediacaran to Middle Cambrian alkaline basalts are widespread along the SMFZ distensive border (Boudda et al., 1979; Destombes and Hollard, 1986; Cornée et al., 1987; Bernardin et al., 1988; Soulaimani et al., 2003; Aarab et al., 2005; Raddi et al., 2007; Pouclet et al., 2008) as well as in the Meseta Domain (El Hadi et al., 2006a; El Kamel et al., 1998; Ouali et al., 2003; Michard et al., 2008, Fig. 3.20);

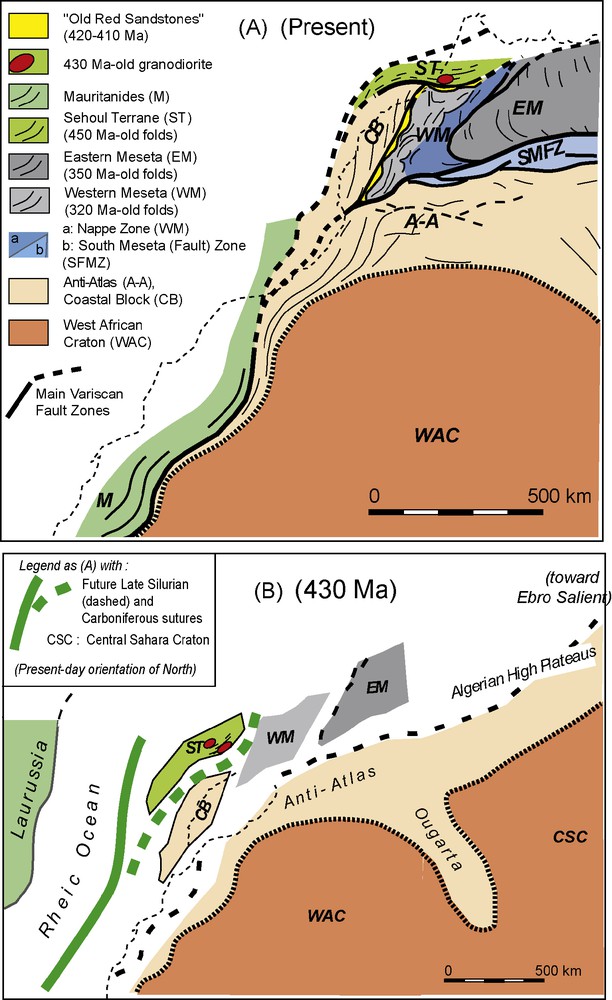

- (iii) Ordovician deposits of the Meseta Domain are most generally thinner and richer in argillites and pelites than those of the Anti-Atlas (Destombes, 1971; Michard et al., 2008). The only exception consists of the westernmost part of the domain, i.e. the Coastal Block, particularly in its southern part (Destombes et al., 1982). Remarkably, the Coastal Block is separated from the Central Block of Western Meseta by a major tectonic zone labelled the West Meseta Shear Zone (Piqué and Michard, 1989). The high stand, shaly Silurian deposits are relatively homogeneous in both the Anti-Atlas and Meseta domains, but a strong differentiation takes place in the Devonian record (Hollard, 1967; Zahraoui, 1994; Michard et al., 2008, Fig. 3.22). The westernmost Meseta (most of the Coastal Block, the Sehoul Block, Rabat-Tiflet Zone and adjoining areas) correspond to shallow platform domains (“Old Red Sandstones facies, reefal carbonates) whereas the areas further east correspond to a turbiditic, basinal domain (Marrakech-Oujda Trough) that does not continue in the Anti-Atlas. Therefore, we assume that the major Meseta sub-domains, i.e. the Eastern and Western Meseta, were separated from NW Gondwana as early as the Early Cambrian by a hiatus of thinned crust (Fig. 2B). Inversion and suturing of this hiatus occurred during the Carboniferous, resulting in the SMFZ.

- 5-. In contrast, we agree with Simancas et al., 2009 when they claim that the Meseta Domain was not separated by any wide ocean during the Devonian-Early Carboniferous [cf.(Piqué and Michard, 1989; Hoepffner et al., 2005; Michard et al., 2008)]. If an oceanic suture occurs in the Moroccan Meseta, it can only be found south of the Sehoul Exotic Terrane, the only piece of the Mesetan mosaic (Fig. 2A) where 450–430 Ma-old orogenic events have been cited (El Hassani, 1994a, 1994b; Tahiri and El Hassani, 1994). In fact, Ordovician spilitic basalts and gabbros occur close to Rabat within the Rabat-Tiflet dilacerated, dextral strike-slip zone at the boundary between the Sehoul Block and central Western Meseta (Cailleux et al., 1984). These metabasites are not ophiolites, but could be taken as a hint for a lost oceanic domain sensu lato [cf. (Hurley et al., 1974)]. This supports Simancas et al., 2005; Simancas et al., 2009 proposal to locate the Rheic suture in this zone (cf [(Simancas et al., 2005), Fig. 4])1.

To conclude, we feel that in order to assess the tectonic correlations between the Moroccan and Iberian segments of the Variscan Belt, it is mandatory to take into account an important separation of the varied Meseta sub-domains after their rifting from NW Gondwana. These sub-domains did not drift thousands of kilometres away, but a significant thinned crust seaway extended likely until the Devonian-Early Carboniferous between these Gondwanan continental allochthons and their mother country.

1 New datations on the Rabat and Tiflet granites have been ultimately provided by Tahiri et al., 2010 (J. Afr. Earth Sci., in press), which suggest an Eo-Variscan, rather than Caledonian age for the Sehoul Block.

Structural map of the South Meseta Fault Zone and adjacent areas of the Moroccan Variscides, after Hoepffner et al. (Hoepffner et al., 2005) and Michard et al. (Michard et al., 2008), modified.

Carte structurale de la Zone de Faille sud-mésétienne et des régions voisines des Variscides marocaines d’après Hoepffner et al. (Hoepffner et al., 2005) et Michard et al. (Michard et al., 2008), modifiés.

A. Sketch map of the mosaic of structural domains that constitute the Moroccan Variscides. B. Tentative restoration of their position by the end of the “Caledonian” (Acadian) event that affected the Sehoul Terrane.

A. Carte schématique des domaines structuraux qui constituent les Variscides marocaines. B. Essai de restauration de leur position à la fin de l’évènement « calédonien » (acadien) qui a affecté le « Terrain » des Séhoul.