1 Introduction

There are several technical solutions for domestic waste management: recycling, incineration with or without energy recuperation (recovery) and burying. In Algeria, burying is the solution that has been developed for the last 10 years. During the same period, around 50 technical burying centers or landfills were realized.

The main environmental risk linked to landfill exploitation is ground water contamination due to infiltration of leachates containing heavy metals such as Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn. In order to prevent this risk, Algerian regulation requires that a 1 meter-thick layer of clay, whose saturation permeability must be less than 10−9 m/s1, be set up on the landfill's bottom and flanks. This clay layer is used as a hydraulic and geochemical barrier.

In the landfills of Saf-Saf, located in the Tlemcen Wilaya region, the clay barrier was made of local natural clay (noted AN). The compacting problems of natural clays can cause fissuring problems in the barrier, as these materials are very sensitive to water and can create, as a result, some preferential paths for leachates infiltration.

In order to avoid such problems, a local marine sand, commonly used in civil engineering in the region of Tlemcen, could be mixed with an industrial bentonite made in the nearby region of Maghnia, to obtain a mixture that can be more easily used. We looked for the proportions of this mixture in the context of this study in order to reach the required regulation permeability.

Then, in order to compare the geochemical efficiencies of AN and SB, a synthetic solution, representing the concentrations found in landfill leachates at the international level, has been prepared and put in contact with these 2 matrixes, with various dilution ratios. The results of these sorption experiments helped us to adjust the adsorption isotherm models of Freundlich and Langmuir. The parameters of the adjusted models were compared with those found in the literature, and this allows one to calculate the theoretical maximal capacity of fixing heavy metals using AN and SB. Finally, the assessment of solution concentrations in the different experiments allows observing the effect of both matrixes on leachates.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials used

The main geochemical and physico-chemical properties of natural clay and industrial bentonite are obtained by NF P94-0512, NF P94-0683, NF X31-1304 NF B 35 5065, NF P94-0486, NF P94-0937, NF P 94-0568 and NF P 94-0579 and are shown in Table 1.

Caractéristiques des sols.

| Normes | AN | Bentonite | SB 90-10 | |

| Liquid limit, wL (%) | NF P94-051 | 40 | 230.72 | 37 |

| Plastic limit, wP (%) | NF P94-051 | 22 | 51.51 | 19 |

| Plastic index (%) | NF P94-051 | 18 | 179.21 | 18 |

| Specific surface area (m2g−1) | NF P94-068 | 116 | 579.76 | 73.18 |

| CEC (meq/100g) | NF X31-130 | 19.5 | 73 | 14.8 |

| pH in water | NF B 35 506 | 9.2 | 9 | 10.5 |

| CaCO3 (%) | NF P94-048 | 38.2 | 19.45 | 41.16 |

| Optimal dry density | NF P94-093 | 1.71 | – | 1.81 |

| Optimal water content (%) | NF P94-093 | 18 | – | 14.5 |

| Fines (% < 80 μm) | NF P 94-056 | 78 | 100 | 10.45 |

| Clay (% < 2 μm) | NF P 94-057 | 5 | 70 | 7 |

Bentonite makes a more efficient geochemical barrier than AN. Its specific surface and cationic exchange capacity (CEC) are respectively 5 and 3.7 times higher than those of AN.

Liquidity and plasticity limits as well as the plasticity index of natural clay (AN) are respectively about 6, 2.5 and 15 times lower than those found in bentonite. However, these parameters are 1.08, 1.15 and 1 times higher than in SB. According to Daniel and Koerner (1995), Matrecon (1980), the most suitable soils for constructing waterproof barriers must possess a liquidity limit between 35 and 60%, a plasticity limit between 15 and 30% and plasticity indices between 7 and 40%.

2.2 Synthetic solution

The synthetic leachate was made up of different salts, shown in Table 2, diluted in ultrapure water so as to obtain concentrations corresponding to those found, at the international level, in leachate of domestic wastes landfills (Clément et al., 1993; Kehila et al., 2006; Khatabi, 2002; Kjeldsen and Christophersen, 2001).

Caractéristiques de la solution synthétique.

| Leachate prepared | Leachate characteristics in literature | |||

| pH | 3 | 3–7.79 | ||

| C. E. | (mS/cm) | 12.63 | 6.24–19.14 | |

| Elements | Sels utilisés | |||

| Cl− | MgCl26H2O CaCl22H2O | mg/l Cl | 2624.5 | 590–5325 |

| SO42− | Cu(SO4)5H20 et MgSO4 | mg/l SO4 | 631 | 79.5–3879 |

| NO32− | Zn(NO3)2.Pb(NO3)2 et Cd(NO3)24H20 | mg/l NO3 | 345.2 | 3–660 |

| Na+ | NaOH | mg/l Na | 600 | 780–4767.5 |

| K+ | KOH | mg/l K | 661 | 460–1875 |

| Mg2+ | MgCl26H2O et MgSO4 | mg/l Mg | 412.55 | 50–7515 |

| Ca2+ | CaCl22H2O | mg/l Ca | 1000.77 | 78.5–3605 |

| Cu2+ | Cu(SO4)5H20 | mg/l Cu | 100 | 0.08–8 |

| Zn2+ | Zn(NO3)2 | mg/l Zn | 100 | 0.13–163 |

| Cd2+ | Cd(NO3)24H20 | mg/l Cd | 100 | 0.01–0.2 |

The synthetic solution concentrations of Cl−, SO42−, NO32−, Na+, K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+ are comprised within the range of concentrations recorded at the international level. However, concentrations of Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+ and Pb2+ were increased (80 to 100 mg/l), so that a complete study of the fixing capacity of the matrixes AN and SB with respect to these 4 heavy metals could be made. Indeed, clays like montmorillonite can fix 34, 32 and 31 mg/g of Pb, Cu and Cd, respectively (Bhattacharyya and Sen Gupta, 2007b; Unuabonah et al., 2007).

Furthermore, the pH and electric conductivity (EC) of the synthetic solution correspond to the figures collected at the international level.

2.3 Preliminary sorption experiments

The adsorption isotherms are established using 5 necessary measuring points. The synthetic solution (mother solution) was used to prepare 4 other solutions with dilutions 1/2, 1/10, 1/20 and 1/50. In order to determine the length of time required for sorption experiments of the 4 heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn) on both matrices (AN and SB), 2 preliminary experiments were performed in 24 h using the mother solution, with the liquid/solid ratio (L/S) of 50 L/kg, under continuous stirring (23 turns/min). The evolution of the reaction between the mother solution and the matrixes (samples previously dried in the sterilizer) was traced through the evolution of the pH and the electrical conductivity of the solution.

2.4 Adsorption isotherms

The sorption experiments were carried out with the same L/S ratio as the preliminary ones, in closed polyethylene reactors, under stirring and at the surrounding temperature, for a period of time previously determined. At the end of the experiment, the solid and liquid phases were separated by centrifugation (4000 turns/min) and the solutions were then filtered. The analysis of Zn, Mg, K, Ca and Na were carried out by flame spectrometry (equipment Varian SpectrAA 200), and that of Cd, Pb and Cu by oven spectrometry (equipment Varian SpectrAA 220z). Anions were analyzed using ionic chromatography (equipment Dionex DX 100).

The results of sorption experiments on clays were interpreted using Langmuir and Freundlich models (Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively). These models are commonly used to study sorption phenomena of heavy metals on clay particles (Bellir et al., 2005; Bhattacharyya and Sen Gupta, 2006a, 2007a, 2008; Unuabonah et al., 2007; Vieira Dos Santos and Masini, 2007). They particularly allow calculating the maximum adsorption capacity of each metal using different matrixes.

Langmuir:

| (1) |

Freundlich:

| (2) |

ce: equilibrium concentration of metal ion in liquid phase (mg/l);

qe: equilibrium concentration of metal ion in solid phase (mg/l);

Cs: maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g) (adsorption capacity of Langmuir mg/g);

KL: adsorption coefficient of Langmuir (l/mg);

KF: adsorption capacity constant of Freundlich (mgl−1/n L1/n g−1);

nf: adsorption intensity constant of Freundlish.

2.5 Concentration variation

The evolution of heavy metal concentrations in solutions that are in contact with AN and SB matrixes enables us to measure the abatement rate of pollutants in solution (Eq. (3)). A negative value of the rate means a fixation; a positive one means a salting out from the matrix.

| (3) |

Ci: initial concentration of ion (mg/l);

Cf: final concentration of ion (mg/l).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Permeability of materials

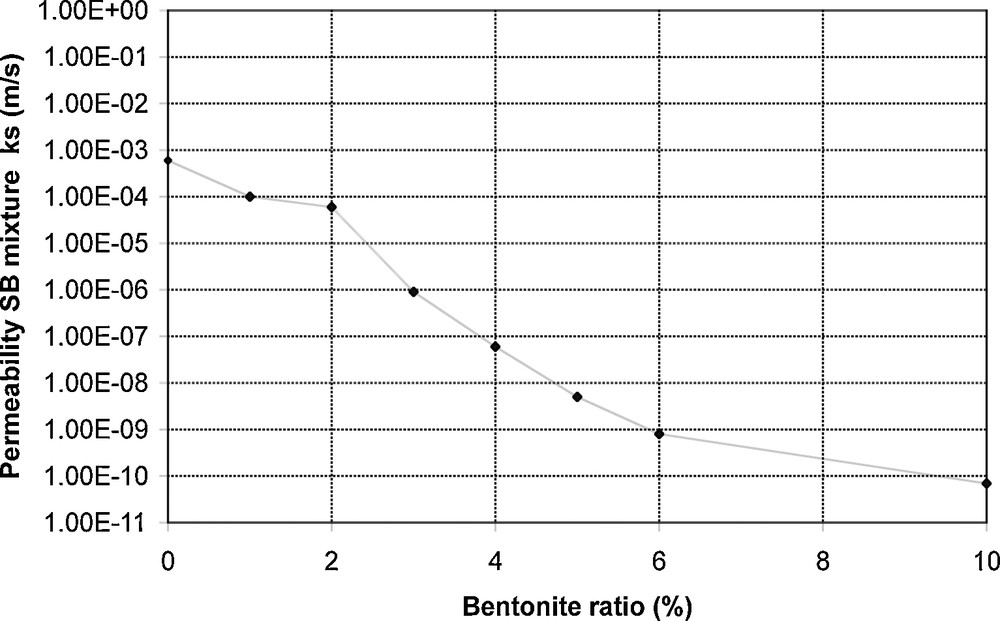

The saturated permeability of AN material was controlled and found equal to 8.5 × 10−11 m/s; this value complies with regulatory requirements. The composition of the SB mixture was established in such a way as to present a similar permeability. The saturated permeability of several mixtures containing 0 to 10% of bentonite was measured (Fig. 1).

Saturated permeability of SB mixtures.

Perméabilité à saturation des mélanges SB.

The SB mixture with 10% of bentonite gives permeability equal to 6.9 × 10−11 m/s. It was used throughout the whole study.

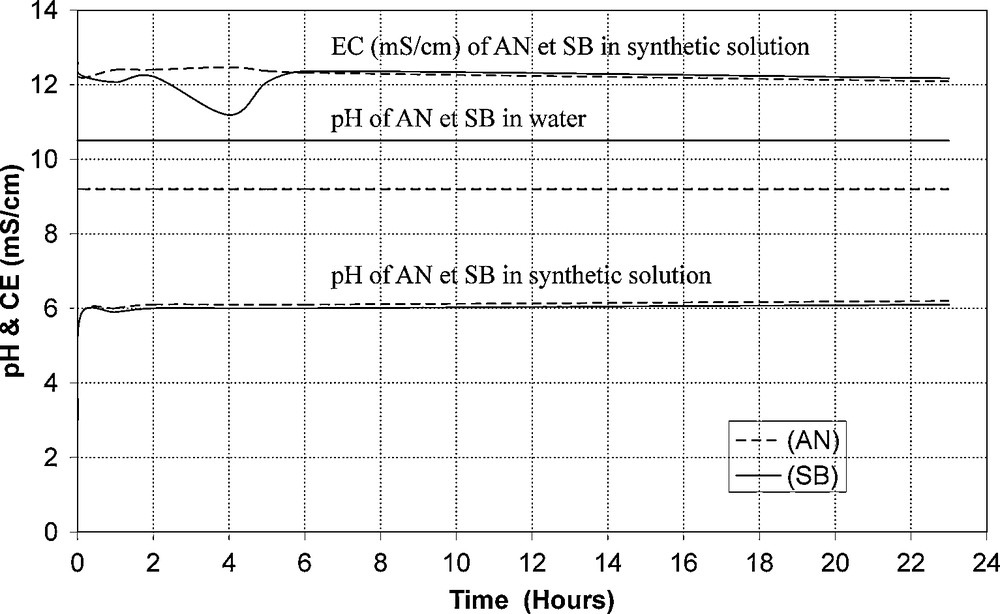

3.2 Duration of sorption experiments

The evolution of the pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of mixtures, between the mother solution and AN and SB matrixes, is shown in Fig. 2. The pH in water of AN and SB materials was respectively 9.2 and 10.5 (standard NF B 35 506). The pH of solutions, originally 3 (Table 2), quickly rose to 6 and 6.1 under the effect of matrixes AN and SB, respectively. This pH remained constant for 24 h. The electrical conductivity (EC) fluctuated around 12 mS/cm at the beginning of the experiments. Five hours later, it stabilizes at 12.2 mS/cm, for both mixtures. From these results, a 5 h-contact time was chosen for all sorption experiments.

Kinetics.

Cinétique.

3.3 Interpretation of isotherms

The Langmuir isotherm, obtained by plotting ce/qe versus ce, is linear. Fig. 3 shows the adsorption of Cu by (SB) matrix. This plot yield 2 important parameters: adsorption capacity of Langmuir Cs, giving the amount of Cu required to occupy all the available sites in unit mass of clay and Langmuir equilibrium parameter KL.

Langmuir isotherm for Cu in SB.

Isotherme de Langmuir de Cu dans SB.

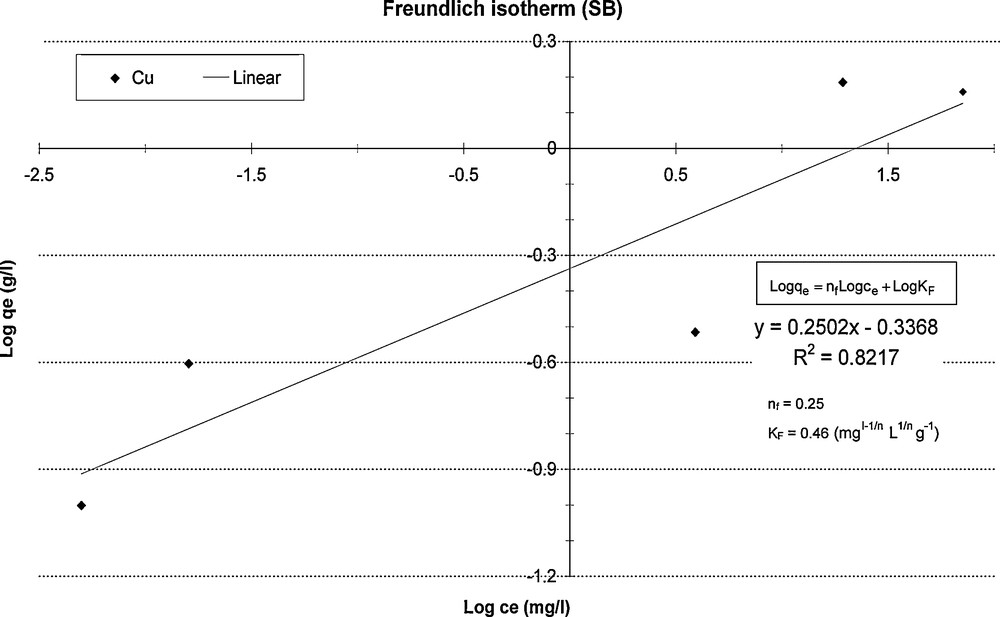

Fig. 4 illustrates the adsorption of Cu in (SB) matrix with Freundlich isotherm, this model was obtained by plotting Log qe versus Log ce, This plot was linear, it gives up 2 parameters: adsorption capacity constant of Freundlich KF and adsorption intensity constant of Freundlish nf.

Freundlich isotherm for Cu in SB.

Isotherme de Freundlich de Cu dans SB.

The parameters from the fit of adsorption isotherms of Freundlich and Langmuir are shown in Table 3. Langmuir model gives correlation coefficients greater than 0.9 for all 4 metals, for both matrixes. The maximum adsorption capacities (Cs), calculated according to this model, are found to be within the range of values reported in the literature for Cu and Pb, for AN and SB matrixes. They are slightly smaller for Cd and Zn. Concerning copper, the values of Cs in the literature are between 0.02 and 30 mg/g (Alvarez-Ayozo and Garcia-Sanchez, 2003; Bellir et al., 2005; Bhattacharyya and Sen Gupta, 2006a, 2008). For lead, the parameters range from 3 to 34 mg/g (Bhattacharyya and Sen Gupta, 2006b, 2007a, 2008; Sen Gupta and Bhattacharyya, 2005), for cadmium, from 3 to 33.2 mg/g (Alvarez-Ayozo and Garcia-Sanchez, 2003; Bhattacharyya and Sen Gupta, 2007b; Sen Gupta and Bhattacharyya, 2006; Uluman et al., 2003), and for zinc, from 0.4 to 52.9 mg/g (Alvarez-Ayozo and Garcia-Sanchez, 2003; Mellah and Chegrouche, 1997).

Coefficients des isothermes de Freundlich et Langmuir.

| Freundlich | Langmuir | ||||||

| Elements | K F | n f | R2 | KL (l/mg) | Cs (mg/g) | R2 | |

| Zn | AN | 0.201 | 0.09 | 0.62 | 1.52 | 0.27 | 0.99 |

| SB | 0.009 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 0.1 | 0.14 | 0.91 | |

| Pb | AN | 1.99 | 0.32 | 0.99 | 1.66 | 4.19 | 0.97 |

| SB | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.94 | 0.33 | 3.84 | 0.94 | |

| Cu | AN | 0.2 | 0.0925 | 0.62 | 0.586 | 2.43 | 0.99 |

| SB | 0.4619 | 0.25 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 1.53 | 0.95 | |

| Cd | AN | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.61 | 14.7 | 0.33 | 0.90 |

| SB | 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.99 |

The adsorption selectivity of all 4 materials is the same, be it for matrix AN or SB: Pb (3.84 to 43.19) > Cu (1.53 to 2.43) > Cd (0.31 to 0.33) > Zn (0.14 to 0.27). Many authors found the same selectivity values (Basta and Tabatabai, 1992; Covelo et al., 2004; Gao et al., 1997; Saha et al., 2002; Veeresh et al., 2003; Vega et al., 2006).

Correlation coefficients obtained from Freundlich model are not as good as those given by Langmuir model. In general, with matrix AN, the adsorption capacities (KF) cannot be interpreted because the coefficients are small, except for lead.

Concerning zinc, in the literature, values of KF range from 2.3 to 8.4 mgl−1/n L1/n g−1 (Mellah and Chegrouche, 1997). For lead, they range from 0.6 to 11.3 mgl−1/n L1/n g−1 (Bhattacharyya and Sen Gupta, 2006b; Mellah and Chegrouche, 1997) and for cadmium, from 0.5 to 12.9 mgl−1/n L1/n g−1 (Bhattacharyya and Sen Gupta, 2007b; Saha et al., 2002). The adsorption selectivity of matrix SB, for the 3 metals is such as Pb (0.64) > Cd (0.01) > Zn (0.009). Several authors found the same selectivity sequence (Basta and Tabatabai, 1992; Covelo et al., 2004; Gao et al., 1997; Saha et al., 2002; Veeresh et al., 2003; Vega et al., 2006).

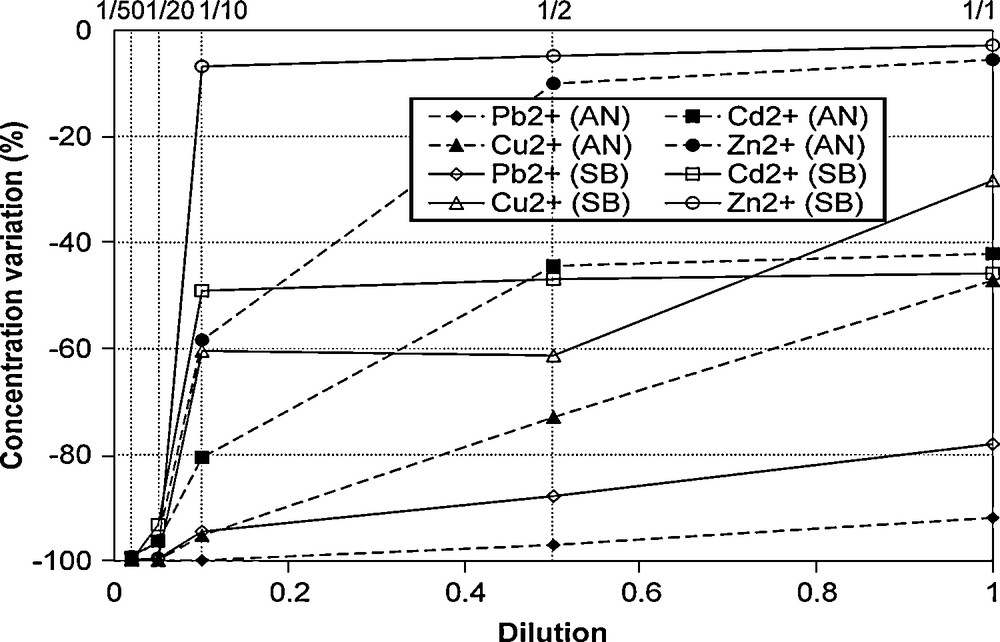

3.4 Variation of solution concentrations

The concentration variations of Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn within solutions in contact with matrixes AN and SB are shown in Fig. 5. For weak concentrations (dilutions 1/50 and 1/20), the metallic charge of the solution is entirely fixed by the matrixes. At higher concentrations (dilutions greater than 1/10), a significant (increasing) part of the metallic charge remains in solution. However, even for the strongest concentration (dilution 1/1), the concentration abatement in lead is much higher than that found in zinc.

Concentration variation during sorption experiments.

Variation des concentrations au cours des essais de sorption.

4 Conclusion

The 90-10 sand-industrial bentonite mixture offers the same capacities of geochemical and hydraulic barrier as natural clay, and presents the advantage of being easier to use, as well. The isotherm models applied to sorption results of Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn on both matrixes AN and SB present a better fit with Langmuir model than with Freundlich model. The adsorption capacities (Cs) of both matrixes exhibit the following adsorption selectivity such as Pb > Cu > Cd > Zn. The suggested SB mixture can give sorption capacities equivalent to those of natural clay AN. The sorption experiments carried out with dilution 1/50, more consistent with Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn concentrations recorded in landfill leachates, suggest that the capacity of both matrixes can fix all the metallic charge in solution. Leachates contain non metallic cations as well, capable of reacting with metals and matrixes. Their interactions (competition, substitution) must be studied, as well.

1 Algerian Norm, 2002. Avant projet d’arrêté ministériel fixant les prescriptions techniques relatives au centre d’enfouissement techniques. Algérie.

2 NF P94-051, 1999. Détermination des limites d’Atterberg – Limite de liquidité à la coupelle – Limite de plasticité aurouleau. AFNOR, Paris.

3 NF P94-068, 1998. Sols: reconnaissance et essais – Mesure de la capacité d’adsorption de bleu de méthylène d’un sol ou d’un matériau rocheux – Détermination de la valeur de bleu de méthylène d’un sol ou d’un matériau rocheux par l’essai à la tache. AFNOR, Paris.

4 NF X31-130, 1999. Détermination de la capacité d’échange cationique (CEC) et des cations extractibles. AFNOR, Paris.

5 NF B 35 506, 1994. Qualité des sols – méthodes chimiques – Détermination du pH. AFNOR, Paris.

6 NF P94-048, 1996. Reconnaissance et essais – Détermination de la teneur en carbonate – Méthode du calcimètre. AFNOR, Paris.

7 NF P94-093, 1999. Reconnaissance et essais – Détermination des références de compactage d’un matériau – Essai Proctor normal. Essai Proctor modifié. AFNOR, Paris.

8 NF 94-056, 1999. Détermination de la granulométrie par tamisage. AFNOR, Paris.

9 NF P 94-057, 1999. Détermination de la granulométrie par sédimentométrie. AFNOR, Paris.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier