1 Introduction

The Paleoproterozoic terranes of the West Africa Craton (WAC) are composed of large sedimentary basins and linear arcuate volcanic belts which constitute geographically separated areas (Fig. 1a).

Location map of Kédougou-Kéniéba Inlier (KKI) within the West African Craton (WAC). a- Schematic map of the major Precambrian shields of the WAC (simplified from (Gueye et al., 2008)). (1) Limits of the WAC. (2) Post-Paleozoic cover. (3) Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic. (4) Pan-African and Hercynian belts. (5) Lower Proterozoic. (6) Archean. b- Schematic geological map of the KKI, locating the study area (modified after (Bassot, 1997)). (1) D2 major shear zones. (2) Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic. (3) Dialé-Daléma Supergroup (DDS). (4) Carbonates. (5) Calc-alkaline volcanic rocks. (6) Saraya and Badon-Kakadian Batholiths. (7) Boboti clinopyroxen bearing granitoid.

Carte de localisation de la boutonnière de Kédougou-Kéniéba (KKI) dans le Craton Ouest Africain (WAC). a- Carte schématique des principaux boucliers précambriens du WAC (simplifiée de (Gueye et al., 2008)). (1) Limites du WAC. (2) Couverture post-paléozoïque. (3) Néoprotérozoïque et Paléozoïque. (4) Ceintures pan-africaines et hercyniennes. (5) Protérozoïque inférieur. (6) Archéen. b- Carte géologique schématique de la KKI, localisant le secteur d’étude (modifiée d’après (Bassot, 1997)). (1) Cisaillements majeurs D2. (2) Néoprotérozoïque et Paléozoïque. (3) Supergroupe de Dialé-Daléma (DDS). (4) Carbonates. (5) Roches volcaniques calco-alcalines. (6) Batholithes de Saraya et Badon-Kakadian. (7) Granitoïde à clinopyroxènes de Boboti.

The organisation of the Paleoproterozoic terranes of the WAC results from a complex polycyclic structural evolution (Bard, 1974) related to the Eburnean orogen (Bonhomme, 1962). Such Paleoproterozoic terranes indicate, through a detailed age mapping, a general southeast-northwest oriented diachroneity in crustal development and regional deformation (Hirdes and Davis, 2002). Nevertheless, the evolution of the Eburnean orogen is characterized by two (Ledru et al., 1989) or three (Milési et al., 1989a) major deformations in most of the areas of the WAC.

The first D1 phase results from a thrusting tectonic occurrence at ca. 2110 Ma (Bonhomme, 1962; Feybesse et al., 2006) with variable metamorphic grades from one area to another. In the Kédougou-Kéniéba inlier (KKI), according to Ledru et al. (Ledru et al., 1989), D1 phase is interpreted as a thrusting tectonic regime. It is characterized by a SW-NE to north-south trending S0S1 schistosity, synchronous to greenschist grade metamorphism occurring parallel to axial surfaces of P1 folds. This deformation affects dominantly sedimentary formations of the Lower Birimian B1 (Ledru et al., 1991) as well as metavolcanites and metasediments of the Mako Supergroup (Bassot, 1987; Bertrand et al., 1989).

D2 phase is at the origin of large main folded structures exhibiting sub-vertical axial planes and sub-horizontal SW-NE axes at a regional scale and of a first generation of shears north-south to SW-NE oriented, mostly sinistral (Bassot and Dommanget, 1986; Feybesse et al., 1990a; Feybesse et al., 1990b). Locally it produced thrusting along SW-NE oriented planes, particularly in Ghana (Milési et al., 1992). Penetrative deformation associated with such folds is generally a sub-vertical schistosity synchronous to greenschist metamorphic facies or a contact metamorphism in the vicinity of granitic intrusions. Ductile shear zones are large mylonitic corridors which were active during a greenschist facies metamorphic event (Lemoine, 1982; Liégeois et al., 1991). D2 deformation is at the origin of the emplacement of numerous granitic intrusions in the Proterozoic terranes (Ledru et al., 1989; Pons et al., 1992). In the KKI, on a local scale, this deformation represented by a large SW-NE oriented antiform, associated with S2 axial plane schistosity, produced folding of first S0S1 schistosity. Major north-south shear zones are also associated to D2 deformation. The most prominent are the Senegalian-Malian Fault (SMF) (Bassot and Dommanget, 1986) and the Main Transcurrent Shear Zone (MTZ) system (in (Ledru et al., 1991)). These faults acted simultaneously during the emplacement of a set of syn-tectonic Paleoproterozoic plutons GII (Sandikounda Layered Pluton Complex, Laminia Kaourou Plutonic Complex, Tomoromadji-Birmassou) and GIII (Diombalou, Bouroumbourou and Sanssankhoto) of the Mako Supergroup (Gueye et al., 2008) between 2160 and 2090 Ma (Dia et al., 1997). Saraya, Boboti and Gamaye plutons from the Dialé-Daléma Supergroup emplaced at the same period of time (Ledru et al., 1991; Valéro et al., 1986).

D3 deformation was first described in Burkina Faso (Feybesse et al., 1989), recorded within a folding accompanied by large shear zones, often dextral. It shows a N50° to N80° S3 oriented schistosity, with a SSW-NNE or WNW-ESE stretching lineation showing various dips. This D3 deformation has also been recognized in other Birimian areas of the WAC, mainly in Ghana (Ledru et al., 1988), Guinea and the Ivory Coast (Feybesse et al., 1989). It displays dextral shearing, reworking fractures mostly resulting from D2 deformation. Both the D2 and D3 phases are transcurrent.

In South-East Senegal, the interpretation of Eburnean tectonics regarding the style of deformation is poorly understood. In the Kolia-Boboti sedimentary Basin (KBB), east of the Dialé-Daléma Supergroup, few researchers have focused on the characterization of the tectonic style of deformation (Ledru et al., 1989; Ledru et al., 1991; Milési et al., 1986).

This paper is twofold. Its aim is to 1- characterize the spatio-temporal deformation of the Eburnean structures through the relationships existing between the various structural elements and 2- to propose a possible structural evolution of the style of the major tectonic events.

2 Geological setting

The KKI, overlying in the south-eastern Senegal, is a portion of the large Paleoproterozoic terranes of the WAC (Fig. 1a). It is bounded by Neoproterozoic sediments of the Taoudeni basin (Fig. 1b). Bassot (Bassot, 1987) subdivided the Paleoproterozoic rocks of the KKI into the Mako Supergroup in the west and the Dialé-Daléma Supergroup in the east. They are separated by a regional crustal scale shear zone, the MTZ, which is globally SW-NE to north-west trending from south to north (Fig. 1b).

The Mako Supergroup largely consists on mafic-ultramafic and felsic volcanic rocks intruded by numerous granitic plutons. The Mako volcanic assemblage is dated in the range of 2213–2196 Ma and the ages of their granitic intrusions lie between 2160 and 2070 Ma (Dia et al., 1997; Pawlig et al., 2006). The volcanic packages and the granitoids are interpreted to have been island arc affinities on the basis of geochemical and petrological data (Dia, 1988; Dia et al., 1997; Diallo et al., 1993; Pawlig et al., 2006).

The Dialé-Daléma Supergroup (DDS) is composed of sedimentary rocks including volcanoclastics to calc-alkaline volcanic rocks and is intruded in its centre by the plutonic complex of Saraya and the plutons of Balangouma and Boboti (NDiaye et al., 1997). The lithologic succession of the DDS was established by the Senegalian-Sovietic party for Gold research (Mission de recherche, 1970–1973) who defined two lithological groups in the DDS. The lower group (B1) comprises sandstones, quartz-bearing wackes, greywacke alternances with strong tourmalinized levels, and carbonates. The upper group (B2) is composed of greywackes, schists, pelites and intercalated beds of conglomerates. The clastic rocks of the DDS were interpreted to have been deposited in an intra-cratonic basin (Bassot, 1997; Ledru et al., 1991). Milési et al. (Milési et al., 1986) distinguished from base to top: (1) turbidites with argillite intercalations; (2) strongly tourmalinized sandstone; (3) siltstone and carbonate intercalated with acid pyroclastics and intruded by acid to intermediate dykes. Rare massive sulphide bodies and the great Falémé iron-ore deposits lie in the topmost stratigraphic position.

The lithological succession of KKI is highly controversial concerning the priority between the sedimentary basin series of DDS and the volcanic belt series of Mako Supergroup (Abouchami et al., 1990; Bassot, 1966; Dia, 1988; Ledru et al., 1989; Milési et al., 1989a, 1989b; Ngom, 1989). The controversial lithostratigraphy of the KKI is not directly incident to this paper.

The structural evolution of the Paleoproterozoic terranes in the WAC is interpreted in terms of monocyclic or polycyclic tectonic phases by different authors. The basis of monocyclic interpretation is either the geosynclinal model or a Phanerozoic plate-tectonic model (Abouchami et al., 1990; Bassot, 1966; Leube et al., 1990). The monocyclic evolution implies that deformation of the series would have occurred after the major phase of accretion and before the fluvio-deltaic deposits. The basis for the polycyclic evolution is the polyphased character of structural and metamorphic sequences, recognized in different areas of the WAC (Bard, 1974; Ledru et al., 1991; Milési et al., 1992). Bassot (Bassot, 1987) and Bertrand et al. (Bertrand et al., 1989) recognized the polycyclic character of the KKI tectonic evolution, suggesting that the bases of Mako and DDS are almost everywhere polyphased.

According to three main geodynamic models, the Paleoproterozoic tectonics has been interpreted as: (1) collision tectonics similar to the Alpine and Himalayan orogenies (Shackleton, 1986); (2) ridge tectonics with dominant vertical movements (Condie, 1986; Kröner, 1984) and (3) transcurrent tectonics between at least two rigid cratonic blocks (Onstott and Hargraves, 1981; Onstott et al., 1984; Sutton and Waston, 1974).

In Senegal and Mali, the geodynamic evolution of the Birimian formations is characterized by four tectonic events (Ledru et al., 1991): (1) an extensional B1 phase, associated with sedimentary deposits and fissure-rupture volcanics of tholeitic type; (2) a tangential compression deformation D1 phase, with the tendency towards thrusting, affecting the Lower Birimian succession; (3) an extensional B2 phase associated with fluvio-deltaic deposits and calc-alkaline volcanic emissions; and (4) a compressional transcurrent tectonic phase D2, located in the large north-south to SW-NE shear zones and associated with emplacement of granitoids.

3 Structural data

3.1 The Kolia-Boboti sedimentary Basin

The north-south trending Kolia-Boboti sedimentary Basin (KBB) corresponds to the eastern part of the DDS, bounded to the east by the Falémé River and to the west by Boboti pyroxene bearing granite (Figs. 1b, 2a). The KBB includes: (1) quartz bearing wackes, argillites, greywackes which strongly tourmalinized at the base; and (2) alternance of sandstones, greywackes and schists showing some conglomerate lens, and carbonates with acid pyroclastics which are intruded by acid to intermediate dykes at the top. The sedimentary rocks of the KBB gave ages in the range of 2165–2096 Ma (Hirdes and Davis, 2002). An important calc-alkaline volcanic complex (andesites, occasionally rhyolites) took place around 2099 Ma (Hirdes and Davis, 2002; Milési et al., 1989a) between the lower and the upper sediments of the Daléma basin (Bassot, 1987). Later on, the KBB was intruded by several granitoid stocks at around 2000 Ma (Bassot et al., 1984) which partially convert to albitite (Bassot, 1997). The KBB is hosted by Fe, Au and U mineralizations linked to hydrothermal exhalation yielding extensive tourmalinization, chloritization and albitisation (Bassot, 1997; NDiaye, 1994; Wade, 1985).

a1- Lithotectonic map of the Daléma basin (after (Randgold Resources, 2008), modified). (1) Stretching lineation. (2) Fold axis. (3) Foliation planes. (4) Shear zones. (5) Thrusting shear zones. (6) Supposed shear zones. (7) Fine-grained sediments (argillites). (8) Sandstones. (9) Quartzites. (10) Tourmalinized sandstones. (11) Greywakes. (12) Sheared breccias. (13) Granitoids. (14) Andesitic breccias. (15) Andesites. (16) Basalts. (17) Carbonate breccias (cargneules). (18) Albitites. a2- Photograph on a horizontal plane showing sinistral S- type flanking fold structures marked by the development of a fold train followed by a generation of fault or shear zones in the core of the structure within Kolia quartzites. a3- Lower hemisphere equal-area projections of the best-fit finite strain axes and principal planes of strain. Estimate of the strain axes in three zones of the study area (Kolia: x: N29° 21°NW; y: N223° 67°SW; z: N118° 08°SE. Moussala: x: N202° 02°SW; y: N303° 70°NW; z: N106° 19°SE. Linguéya: x: N15° 03°NE; y: N274° 75°EW; z: N107° 15°SE). () Measured slickensides. () Maximum x. () Intermediate y. () Minimum z. (+) Plane poles. a4- Fractures associated with the Riedel model, showing the relationship between the orientation of the main compressional strain axis and the direction of shearing. Synthetic (P,R) and antithetic (R’) faults. a5- Sinistral S/C fabrics evidenced in the cargneules east of Linguéya. b- Schematic A-B cross-section between Moussala and north-west Kolia showing the main P2a asymmetric isoclinal folds, associated with south-east dipping reverse faults. At Kolia, these faults are locally combined with high angle north-west dipping faults, suggesting a “positive flower structure” pattern.

a1-Carte lithostructurale du bassin de Daléma (d’après (Randgold Resources, 2008), modifiée). (1) Linéation d’étirement. (2) Axe des plis. (3) Plans de foliation. (4) Cisaillements. (5) Chevauchements. (6) Cisaillements supposés. (7) Sédiments fins (argillites). (8) Grès. (9) Quartzites. (10) Grès tourmalinisés. (11) Grauwakes. (12) Brèches tectoniques. (13) Granitoïdes. (14) Brèches andésitiques. (15) Andésites. (16) Basaltes. (17) Brèches carbonatées (cargneules). (18) Albitites. a2- Photo sur le plan horizontal montrant des structures senestres de flancs plissés de type S, marquées par le développement d’un train de plis suivis d’une génération de faille ou de cisaillements, au cœur de la structure dans les quartzites de Kolia. a3- Projections à aire égale (hémisphère inférieur) du meilleur ajustement des axes de déformation finie et des plans principaux de déformation. Estimation des axes de déformation dans trois secteurs de la région d’étude (Kolia : x : N29° 21°NW ; y : N223° 67°SW ; z : N118° 08°SE. Moussala : x : N202° 02°SW ; y : N303° 70°NW ; z : N106° 19°SE. Linguéya : x : N15° 03°NE ; y : N274° 75°EW ; z : N107° 15°SE). () Stries mesurées. () Maximum x. () Intermédiaire y. () Minimum z. (+) Pôle des plans. a4- Fractures liées au modèle de Riedel, montrant la relation entre l’orientation de l’axe de raccourcissement principal de la déformation et la direction de cisaillement. Failles synthétiques (P,R) et antithétique (R’). a5- Illustration schématique des structures C/S senestres dans les cargneules à l’est de Linguéya. b- Coupe schématique A-B entre Moussala et le nord-ouest de Kolia montrant les principaux plis isoclinaux asymétriques P2a, associés aux failles inverses à pendage sud-est. A Kolia, ces failles sont localement associées à des failles à fort pendage nord-ouest, suggérant un modèle de « structure en fleur positive ».

All sedimentary rocks are isoclinally folded. Folds are upright or slightly overturned to the south-east (Fig. 2b). The important network of north-south to NE-SE trending transcurrent faults crosscut the KBB. The most important is the SMF.

3.2 Structural elements of Kolia-Moussala corridor

The Kolia-Moussala corridor corresponds to the Senegalese northern part of the SMF. Its north-south oriented structure, 17 km long and 12-13 Km wide, is located just in the south part of the Kolia village (Fig. 2a1). The outcrops are composed of 0.5-1 km wide north-south trending bands of quartzites alternated with argillites, carbonates and shear breccias, albitites, greywackes and granitoid rocks. Occasionally outcrop bands show slightly asymmetric recumbent folds.

The dominant structural feature in the Kolia-Moussala corridor is north-south to SW-NE trending network of crustal scale shear zones. This network is associated with north-south to SW-NE foliation, defined by an alignment of silicate ribbons in the carbonate rocks. The foliation plane is mostly east or south-east dipping and contains well developed N10° to N20° oblique trending stretching lineation, characterized by clastic and aggregate elongations. The foliation is associated with several kinematic indicators, composed of intense S/C fabrics, flanking fold structures and asymmetric recumbent synfolial folds, preserving a predominant sinistral strike-slip (Fig. 2a2).

At Moussala, south-east of Kolia, Eburnean rocks composed mainly of tourmalinized sandstones, argillites and greywackes also crop in north-south linear bands. The linear feature is in relationship with folding and boudinage of different competent layers. The folding axial plane is related to S2 foliation trending north-south to N20°. A north-south to N20° stretching lineation, dipping 20° northward to north-eastward, occurred on foliated planes underlined by aggregates of elongated minerals and clasts.

The main strain axis orientation is established through ductile-brittle structures. In fact, in the competent rocks of the area (albitites, fine-grained greywackes, andesites, etc.), ductile deformation is relayed by ductile-brittle structures (conjugated shear joints, fault exposed furrows, tension cracks, etc.). Geometrical analysis of the ductile-brittle structures like conjugate shear-joints, furrow orientations, allowed us to define the main finite strain axes associated with this Eburnean event. In the Kolia and Moussala targeted zones, the orientation of the main finite compressional strain axis is estimated at around N110° (Fig. 2a3). This directional feature is of high angle (> 45°) compared to the main shear zone trend, suggesting a sinistral transpression (Fig. 2a3,a4). The spatial geometrical relationship between shear zones geometry and main compressional strain axis is comparable to the sinistral Riedel faults system (Fig. 2a4). All these structural features result from a transcurrent and compressional D2 phase of Eburnean orogeny. It is related to a north-south to N20° thinning and a vertical thickening of the Eburnean formations.

3.3 The Linguéya-Boboti corridor

It is an area located between Linguéya at the north and Boboti at the south, limited respectively at the east and the west by the Falémé river and Boboti granite. It is mainly composed of carbonate breccias (cargneules), albitites, argillites, quartzites, basalts, andesites and granitoids. The outcrops are elongated and often present “boudinage” shapes along a north-south to north-east direction. Between Linguéya and Foukola, cargneules show an S- shape fabric, indicating a north-south sinistral shear (Fig. 2a1). S/C structures recognized in the field (S = N90°, C = N40°) corroborate sinistral movement (Fig. 2a5). The shear zones of the Linguéya-Boboti corridor are characterized by a north-south to north-east oriented S2 foliation steeply dipping, mainly eastward. This foliation plane carries a stretching lineation and fold axes oriented from N340° to N25° oriented.

Locally, in the east of Linguéya, the Mandankhoto minor SW-NE thrusting shear zone (MSZ) can be observed. It locally affects the cargneules which display kinematic microstructures (S/C fabrics, synfolial folding) indicating a south-east toward north-west thrusting and a sinistral shearing (Fig. 2a5). Lineation stretching N350° oriented, is highlighted on foliation planes by mineral aggregates. The main axis of compressional strain has the same orientation as that of the Kolia-Moussala sector (Fig. 2a3). These different structural elements can be attributed to the sinistral transpression of Eburnean D2 phase.

3.4 Folding and thrusting structures

The KBB rocks are affected by at least two generations of folds, resulting from polycyclic Eburnean orogeny. At the south of Kolia, P1 folds appear refolded in the hinge of large decametric P2a folds, drawn by quartzite beds within tourmalinized argillites (Fig. 3a). P1 folds are overturned to recumbent folds showing a N040° 20°NE trending axis and a north-west folding vergence. They are synchronous to S0S1 schistosity and affect Lower Birimian B1 tourmalinized fine-grained sediments. Thin sections in the tourmalinized fine-grained sediments and in the volcanic dyke samples show a well-recorded internal schistosity (Si). In the tourmalinized fine-grained sediments, Si is highlighted by quartz inclusions in the tourmaline porphyroblasts. In mafic rocks, Si also appears in the sedimentary inclusions and is underlined by the alignment of tourmaline grains and is coated by S2 (Fig. 3b). This internal schistosity (Si) corresponds to the S0S1 schistosity which often transposed in the stratification plane. It is cross-cut by the north-south to SW-NE foliation which represents the S2 schistosity. P1 folds and S0S1 schistosity could result from north-west vergence shallow thrusting related to the early D1 Eburnean event (Ledru et al., 1991; Milési et al., 1989a; Milési et al., 1992).

(a) Overturned P1 fold appearing in the flank of a P2a fold, emphasized by dark toumalinized levels in argillites at the west of Moussala. (b) Sedimentary inclusion (ES) with an internal schistosity (Si) highlighted by aligned tourmaline (Tm) grains within a mafic rock (RB) exhibiting an S2 schistosity, north of Kolia. Pl: Plagioclase, Qz: Quartz, Mu: Muscovite. (c) Isoclinal asymmetric fold P2a showing drag folds and axial crenulation lineation (Lc) in the fold hinge. (d) Synfolial sub-vertical P2b fold associated with sinistral S/C microstruture fabrics in the Kolia shear zone. (e) Flat thrusting (C), reverse fault (F), S2 schistosity (S) and P2a flattened limb (P) in the Kolia shear zone. (f) “σ clast” wrapped in S2 schistosity, indicating a south-east towards north-west thrust in the argillites, south of Kolia.

(a) Pli P1 renversé visible sur le flanc d’un pli P2a, dessiné par les niveaux sombres tourmalinisés dans les argilites à l’ouest de Moussala. (b) Enclave sédimentaire (ES) à schistosité interne (Si) soulignée par l’alignement de grains de tourmaline (Tm) dans une roche basique (RB) à schistosité S2, au nord de Kolia. Pl : Plagioclase, Qz : Quartz, Mu : Muscovite. (c) Pli isoclinal asymétrique P2a montrant des plis d’entraînement et une linéation de crénulation (Lc) à la charnière du pli. (d) Pli synfolial sub-vertical P2b associé à des microstructures C/S senestres dans la zone de cisaillement de Kolia. (e) Chevauchement en plat (C), faille inverse (F), schistosité S2 (S) et flanc laminé de pli P2a (P) dans la zone de cisaillement de Kolia. (f) « σ clast » emballés dans la schistosité S2, indiquant un chevauchement du sud-est vers le nord-ouest dans les argilites, au sud de Kolia.

The north-south various parallel rock band outcrops result from isoclinal folding, south-east dipping (Fig. 2b). This folding, namely P2a, occurs frequently in the KBB and affects all the sedimentary rocks and locally refolds the P1 folds (Fig. 3a,c). In the Kolia shear zone, P2a folds are characterized by a sub-horizontal north-south to N20° trend axis, slightly curved and dipping northward. In the incompetent rocks, P2a folds show centimetric drag folds which developed crenulation lineation in the fold hinge, sub-horizontal north-south to N20° trending (Fig. 3c). This crenulation lineation is deformed by the P2a folds. The P2a folding is associated with asymmetric recumbent synfolial P2b folds, which are well developed in the shear zone corridors and characterized by N20° trending axes, N60° dipping (Fig. 3d). The P2a fold axes and the crenulation lineations occur at a high angle from each other, defining type II interference fold patterns in the shape of upright or asymmetric early folds and recumbent asymmetric folds. The coexistence of folding and shearing can be understood as the effect of partitioning deformation (Bell, 1981) at mid-crustal-depth. Upright to asymmetric folds within the shear zone have produced vertical thickening, and horizontal thinning and stretching parallel to the shear trend. The P2 folds are associated with the axial schistosity S2 plane and result from the transpressional D2 phase of the Eburnean event.

D2 structures are intersected by thrusting flats and ramps (Fig. 3e) showing north-west vergence kinematic microstructures (Fig. 3f). The thrusting flats correspond to the sub-horizontal plane slightly dipping (> 15°) to the south-east and showing aggregate and mineral elongation stretching lineation that trends N115°. They perpendicularly intersect the sub-vertical S2 schistosity (Fig. 3e). Thrusting ramps show a high-angle dip toward the south-east and carry a sub-vertical N120° trending mineral stretch lineation. Both thrusting flats are associated with SW-NE trending reverse faults, south-easterly dipping which laminated the P2a reverted limbs (Fig. 3e). This thrusting deformation is related to the D2c Eburnean late phase.

4 Discussion and conclusions

The KBB in the eastern part of the KKI is mostly composed of sedimentary and volcanic rocks, intruded by several granitoids. The structural deformation, previously described (Ledru et al., 1989; Ledru et al., 1991; Milési et al., 1986), is characterized by two compressional phases, namely D1 and D2. The D1 phase is a thrusting deformation while the D2 phase is a transcurrrent deformation localized in large north-south to SW-NE shear zone corridors.

The detailed structural mapping of the KBB area allowed us to evidence three Eburnean compressional tectonic phases within these Birimian terranes. The early Eburnean compressional D1 phase affects the Lower Birimian sedimentary rocks. This thrusting deformation is associated with isoclinal overturned folds P1, N040° 20°NE trending axes (Fig. 3a). The S0S1 foliation corresponding to the P1 fold axial plane is often transposed in the stratification plane. In thin sections, S0S1 schistosity is recorded (1) under an internal schistosity shape (Si) within ante-kinematic porphyroblastic grains of tourmaline and (2) by fine-grained tourmalines in sedimentary inclusions within mafic rocks. This internal schistosity is wrapped in the S2 schistosity (Fig. 3b). The D1 Early Eburnean compression was also described and interpreted (Ledru et al., 1991) as a fairly high crustal-level tectonic activity.

The Eburnean compressional and transpressional D2 phase is the second orogeny event. Transpression usually describes a style of deformation that involves collisional orogen accompanied by strike-slip shears across a given zone. The D2 phase is a continuum of deformation that started by a compressional deformation D2a, continued by the D2b transpressional deformation (Fig. 4) and ended by D2c thrusting (Fig. 3e). Compressional deformation is responsible for large isoclinal P2a folds, while transpressional deformation produces simultaneously P2b synfolial recumbent folds, and north-south to SW-NE shear zones. Transpressional deformation is also responsible for the deformation of crenulation lineation of the P2a folds (Fig. 4a) and the curvature of fold axes (Fig. 4b,c). Oblique movements resulting from transpressional deformation is recorded on foliation planes by a stretching lineation dipping 20-25° toward the north – north-east. This oblique movement took place mainly in the north-south to SW-NE slip-thrust faulting, dipping toward the south-east. The angle between the orientation of the main compressional strain axis and the direction of shearing is higher than 20° (Fig. 2a4). However, in the shear zone of Kolia, the core of the SMF, these high-angle faults change progressively and dip toward the north-west (Figs. 2b, 4a). The geometry of such a slip-thrust can be interpreted as a “positive flower structure” (Fig. 5). The obliqueness of the north-south and SW-NE trending faults and the association of co-planar thrusting and strike-slip faults, also evidenced a “positive flower structure” (Ramsay and Huber, 1987; Sylvester, 1988). These transpressional faults would be an ultimate expression, on the surface, of a north-south deep-rooted sinistral shear contact (Fig. 5). In fact, experimental studies show that slip-thrusting faults are either straight or curved but converge at the basement of structures (Richard and Cobbold, 1989). These faults are more vertical when the strike-slip rate is important. Analyses of the main strain axes, based on the geometry of ductile-brittle structures, indicate that the maximum compressional axis appeared with a high rotation angle (> 20°) around a sub-vertical axis regarding the local boundary zones (Fig. 2a2,a3). This is consistent with high angle oblique sinistral shortening (i.e. pure shear dominated transpression). The orientation of the main strain axis may locally vary, especially in the southern part of the study area where the maximum compressional axis is trending ∼N160°. This is to be investigated in a further study. The characterization of a D2 compressional and transpressional phase, showing a “positive flower structure”, constitutes a new feature pattern in the evolution of the Eburnean orogeny of the KKB.

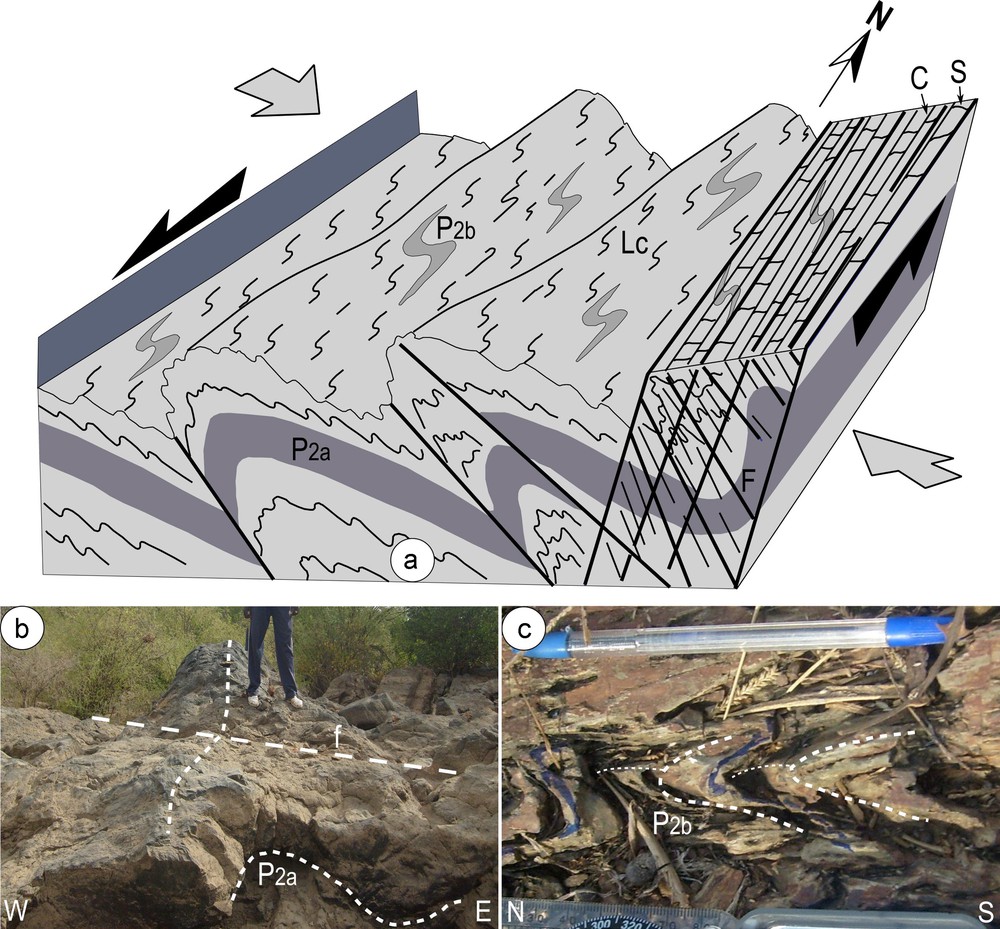

(a) 3D schematic pattern showing how different structural features are related: P2a and P2b folds, crenulation lineation (Lc), S/C fabrics, north-west and south-east dipping reverse faults (F) in the Kolia shear zone. Grey arrows represent the major shortening direction, black arrows show strike-slip movement. Photographs of curved axes P2a (b) and P2b (c) folds observed at Kolia and Moussala respectively. f: fracture.

(a) Modèle schématique 3D montrant la relation entre les détails des différentes structures : plis P2a et P2b, linéation de crénulation (Lc), structures C/S, failles inverses à pendages nord-ouest et sud-est (F) dans la zone de cisaillement de Kolia. Les flèches grises représentent la direction du raccourcissement principal, les flèches noires montrent le mouvement de décrochement. Photos de plis à axes courbes P2a (b) et P2b (c) observés respectivement à Kolia et Moussala. f : fracture.

3D Transpressional model showing a “positive flower structure” and its behaviour at depth in the Kolia shear zone. Same notations as in Fig. 4.

Modèle de transpression 3D montrant une « structure en fleur positive » et son comportement en profondeur dans la zone de cisaillement de Kolia. Mêmes notations qu’en Fig. 4.

The D2c phase of thrusting is the late deformation event recorded by the KBB formations. It is characterized by north-westward thrusting flats and ramps, well displayed in the Kolia area through kinematic microstructures (Fig. 3f). Thrusting structures intersect D2 structures. They are associated with reverse faults which create rupture and lamination of P2a reverted limbs (Fig. 3e). The D2c thrusting phase has been implicitly recognized in the Mako Supergroup by Gueye et al. (Gueye et al., 2008) to be responsible for the emplacement of the GIV granitoids of Mamakono and Tinkhoto. South of the WAC, Milési et al. (Milési et al., 1992) also recognized locally the Late Eburnean D2c thrusting phase, similar to that occurring in the KBB. This D2c thrusting phase must be more documented in the Birimian terranes of KKI.

The identification of D2a compressional and D2b transpressional phase, and D2c thrusting phase of north-west vergence, which are at the origin of the described “positive flower structure”, and flats and ramps thrusting in the KBB respectively, provides new insights into the tectonic evolution of the Eburnean orogeny of the KKI. For the structural evolution of the KBB, the eastern part of the KKI, we evidenced two major compressional phases (D1 and D2), separated by extensional deformations, characterized by sedimentary deposits and volcanic streams.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to D. Mbaye and the staff of the Rangold Resources (Senegal) for their assistance and the logistics in the field. We are grateful to both the two anonymous referees for their constructive comments which helped us to improve the final version of the manuscript.