1 The nuclear waste issue

Nuclear power plants worldwide produce annually several thousands tons of spent fuel. In some countries, spent fuel is considered as waste, but in other countries, like France, it is reprocessed to extract uranium and plutonium. Two groups of waste elements are obtained at this stage: minor actinides and fission products. Minor actinides are transuranic elements produced by one or several neutron captures on 238U. There are isotopes of Am, Np, or Cm with half-life ranging from 2.1 Ma (237Np) to 18 years (244Cm). All are α emitters, with a decay scheme connected to the “natural” decay chains of U, Th, or Np. Minor actinides and their daughter elements are the main source radioactive hazard in nuclear waste. Fission products are nucIei resulting from the splitting of 235U or other fissile elements. Some of them are radioactive (β emitters), with a half-life long enough to accumulate in the spent fuel. Those with short half-life disappear in few years during the cooling stage, but some will be present in waste for durations similar to minor actinides, notably 135Cs (2.3 My), 99Tc (210 000), and 129I (15.6 Ma). The actual waste obtained after reprocessing is then a complex mixture of radioactive and non-radioactive nuclei, including some long-lived radioactive isotopes which must be stabilized in a safe and robust waste form. In France, this is a boro-silicate glass (R7T7), which has several advantages: it incorporates many different chemical elements, has a low surface-to-volume ratio, and can be made through a simple industrial process with 100% incorporation efficiency. Experimental studies and modelling have shown that R7T7 glass should be reasonably durable in geological environment (Vernaz, 2002; Vernaz and Dussossoy, 1992; Vernaz et al., 2001). The high resistance of R7T7 to leaching results mainly from the formation of a protective amorphous silica-rich layer. The main weakness of a glassy waste form is also well-known: fundamentally, a glass is a metastable material which tends to recrystallize, although this process can be very slow (Grambow, 2006, Grambow and Giffaut, 2006). Both devitrification and the formation of a protective amorphous layer are complex processes, which are difficult to model in a complex, radioactive, geological system, when very long time periods are considered (Grambow, 2006). At present, best estimates indicate that the dissolution rate of R7T7 immersed in water, after a short initial period at 1 g/m2/d, reduces by a factor of 104 in a maximum of few months (Vernaz et al., 2001).

2 Crystalline waste-forms

Crystalline waste-forms have been considered for a long time (Lutze and Ewing, 1988). Because crystals are more stable than glasses, ceramics are expected to be several orders of magnitude more durable than glasses. Moreover, as crystals are stable compounds with definite thermodynamics and kinetics properties, modelling and predicting the long-term behaviour of a crystalline waste form is expected to be more robust than for glasses (Oelkers, 2001). However, as crystals are usually produced as powders, a crystalline waste form must be a dense ceramic in order to reduce the surface-to-volume ratio.

Oxide ceramics consist of an ordered assemblage of atoms, linked by iono-covalent bounding, in which oxygen is the main anion. A crude, but efficient model for oxides is to consider that ionic bonds are dominant, and that each ion is a rigid sphere with a definite ionic radius (Pauling's rules, Pauling, 1929). Each cation, (and most radioactive waste elements are cations with the exception of 131I), is surrounded by anions. Because anions are bigger than cations, the crystalline structure is mainly a stacking of anions letting cavities filled by cations. The number of anions around cations, known as the coordination number, depends on the anion/cation radius ratio.

In nuclear waste forms, the radioactive element content should be limited to a few weight percent, in order to avoid an increase of the temperature, a fast destruction of the crystal net by radiation damage, and, for fissile elements, problems of criticality. Incorporation of a radioactive element in a crystalline structure is then a classical substitution problem: a minor element replaces a major element in the crystal lattice. Substitutions rules for ions are by-products of Pauling's rules: (1) the radius of the substituting ion must be similar to that of the nominal ion, but actually depends also on the shape of the polyhedron and on the softness of the structure; (2) if the ion charge is not the same, it must be compensated by another substitution elsewhere in the structure. It is also empirically established that it is easier to replace an ion by a slightly smaller one than the reverse. These rules are now rationalized by recent experimental and theoretical evidence of a full relaxation of cationic sites around substituted elements (Juhin et al., 2008).

As a consequence of these rules, a given structure can accept only some specific substituted elements. It is then difficult to design a crystalline structure which could accommodate all the waste elements produced by spent fuel reprocessing. A specific waste form should be designated for each element, or at least for each group of chemically similar elements. A major consequence is that utilization of crystalline waste forms at an industrial level would require each element, or each group of chemically similar elements, to be selectively extracted from the spent fuel. This is a major technological challenge but considerable progress has been made on that subject, at least at the laboratory scale. Conditioning nuclear waste in crystalline forms is now a promising alternative solution to glassy waste-forms.

3 Performance criteria for crystalline waste-forms

Conditioning nuclear waste in glass has been proven to be a robust method even at industrial scale. If crystalline waste forms pretend to replace glass, it must constitute a very significant progress in all aspects, to counterbalance the difficulty of the separation. The criteria qualifying a crystalline structure as a nuclear waste form can be summarized as follows:

- • ability to incorporate, in the crystal lattice, a significant amount of waste element;

- • durability in natural fluids significantly higher than glass;

- • some kind of resistance to self-irradiation, or at least, no major degradation of the performance from radiation damage, especially the resistance to natural fluids;

- • availability of the major constituents at a reasonable cost;

- • possibility to process the waste form at industrial level in a highly radioactive environment. Melting-cooling process, used for glass, or cold pressing-sintering process, used for fuel should be favoured. Any step with aqueous solution must be avoided for fissile elements.

Some other criteria can be:

- • for fissile elements, ability to incorporate also neutron absorbers to reduce problems of criticality;

- • ability to incorporate several waste elements (for example: all actinides, or all actinides and rare-earth elements), in order to reduce the difficulty of the separation step;

- • tolerance of the process to impurities which may be present after separation;

- • low cost of the process and raw material;

- • high level of scientific and technological knowledge for the waste form and the process.

4 Minerals and the nuclear waste issue

A mineral is crystalline material for which at least one natural occurrence exists. At present, 4350 minerals are considered as valid species by the International Mineralogical Association (Nickel and Nichols, 2008), but only a few hundred are common minerals, and less than fifty are very common. Many of man-designed crystalline materials are similar to a mineral, at least for their crystal structure, and are, abusively from the mineralogist's point of view, referred to by a mineral name. Good examples of this “abuse” are perovskite (CaTiO3) or magnetite (Fe3O4). As already pointed out by several authors (Ewing, 2001), mineralogy is a powerful tool for designing nuclear waste forms, because it provides decisive data dealing with their long-term behaviour in natural environment.

For a given element, mineralogy allows to select crystalline structures compatible with natural environment and various conditions. A survey of mineralogical literature and databases allows determining the kind of structure which can accept this element, and the stability limits of the structure in terms of temperature, pressure, redox state and chemical conditions. Mineralogy provides also direct or indirect data relative to the stability and resistance of a waste form to natural fluids. To deal with that problem, the most interesting source of data is the mineralogy of placers in natural sands. In sands, mineral grains are former crystals from hard rocks, which have been destroyed by weathering and erosion. Chemically and mechanically resistant mineral grains, like quartz, are isolated in this process, transported by rivers down to the ocean or lakes, and accumulate forming various types of sands. Minerals which are denser than quartz accumulate in specific layers named placers (Roy, 1999; Van Emden et al., 1997). To estimate the resistance of a mineral, marine placers are the most interesting ones because only the most durable grains can survive to a combination of long transport from source rocks down to ocean, mechanical abrasion by waves, and chemical aggression by seawater.

Finally, the mineralogy of radioactive minerals allows estimating the resistance of a waste form to radioactive damage (Lumpkin, 2001). In most rock types, uranium and thorium are trace elements concentrated in few radioactive accessory minerals. The accumulated radiation damage may be high enough to amorphize the crystal lattice of radioactive minerals, sometimes up to an amorphous “metamict state” (Ewing, 1993). For all U- or Th-bearing minerals, we can determine from natural occurrences how they are affected by radiation damage, how they recover, or how radiation damage modifies their chemical and mechanical properties. Natural radioactive minerals are the only source of information for long-term accumulation of radiation damage in crystals. However mineralogy cannot provide data relative to elements which do not exist in nature, nor which do not have any natural analog, such as technecium.

5 Mineralogist's point of view for some waste-forms

5.1 Minor actinides waste-forms

Zircon is the natural zirconium orthosilicate (ZrSiO4, I41/amd). Its structure consists in chains of alternating SiO4 tetrahedra and ZrO8 polyhedra. Zircon is one of the most resistant minerals on Earth. It is abundant in placers, and numerous geochronological studies have shown that it can survive to at least one complete magmatic-erosion-transport-deposition-magmatic cycle (Dunn et al., 2005, Nelson et al., 2000). It accommodates natural tetravalent actinides U4+ and Th4+ in its structure by simple exchange with Zr4+. Trivalent rare earth (REE3+), which are analogs of trivalent actinides and are neutron absorbers, can be incorporated by a coupled P5+ + REE3+ = Zr4+ + Si4+ substitution. Zircon have been proposed as an host for military plutonium, since PuSiO4 displays the zircon structure, with Pu4+ ionic radius being 0.96 Å in PuO8 close to Zr4+: 0.84 Å (Burakov et al., 2002; Ewing et al., 1995). Other actinides Np (0.98 Å), Am (1.09 Å), Cm (1.08 Å) can be incorporated, too, in a limited amount, in a way similar to natural REE (Burakov et al., 2008; Zamoryanskaya et al., 2002). As both ZrO2 and SiO2 are available materials, dense zircon ceramics can be readily manufactured (Burakov et al., 2002). Although mineralogy and geology tell us that zircon is extremely durable, it is well known too, from geochronological studies, that zircon becomes quickly metamict by self-irradiation and that when metamict, the chemical durability of zircon is largely reduced (Balan et al., 2001; Delattre et al., 2007; Geisler and Pidgeon, 2002). The main concern with zircon is clearly that its metamictization rate should be greatly increased by incorporation of α emitters with half-life shorter than that of natural U or Th.

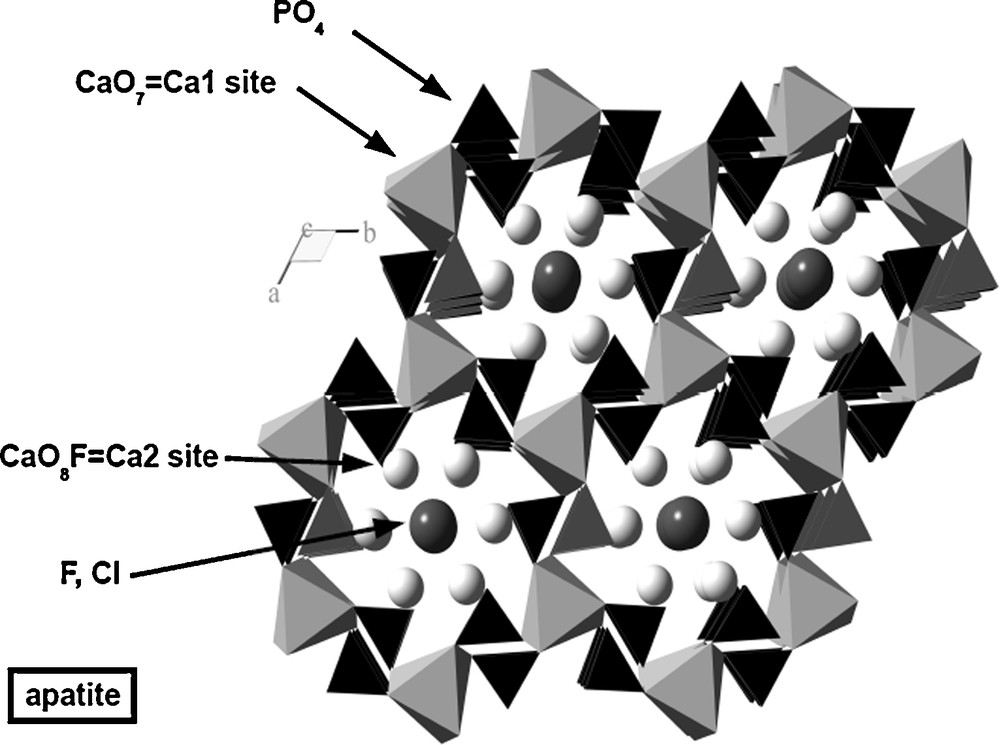

Apatite (Ca5(PO4)3F2 for fluorapatite, P63/m), is a complex structure, with a honeycomb-like organization (Fig. 1). Apatite has been proposed as a waste form because it trapped some Pu and REE around the Oklo fossil nuclear reactors (Bros et al., 1996; Horie et al., 2004). Three polyhedra coexist in apatite: the PO4 tetrahedron, and two sites for calcium: CaO9 (Ca1 site) and CaO6F (Ca2 site). Fluorine, which can be replaced notably by Cl and OH, fills channels surrounded by the Ca2 sites. The Ca1 site is significantly larger (about 32 Å3) than the Ca2 site (22 Å3). Apatite is a very flexible structure: Ca2+ can be replaced by many divalent cations with ionic radius around 1 Å, but also by trivalent and tetravalent ions of the same size, such as REE3+, U4+ and Th4+(Pan and Fleet, 2002). U and Th are dominantly incorporated in Ca2 site (Luo et al., 2009). Charge compensation is achieved by simultaneous exchange on Ca or P sites: REE3+ + Na+ = 2Ca2+ or REE3+ + Si4+ = Ca2+ + P5+. When P5+ is replaced by Si4+, the mineral is named britholite. All minor actinides can be incorporated in the apatite structure. Apatite is made of very abundant elements and can be shaped as ceramics (Ben Ayed et al., 2000; Brégiroux et al., 2003). Apatite is a common mineral in placers, but geological arguments indicate that it is less durable than zircon since it is subject to dissolution-precipitation at shallow levels on the Earth (Filipeli, 2002), and since it can be consumed by living organisms. The main weakness of apatite lies in the presence of F-bearing channels. Fluorine is weakly bounded in this position and its preferential extraction during leaching (Dacheux et al., 2004) lets the channel open, making elements in the Ca2 site readily reachable by water. On the other hand, apatite is highly resistant to radiation damage, due to easy self-healing (Ouchani et al., 1997).

Representation of apatite structure projected on the basal plane along the c-axis, 6-fold symmetry axis. Note the channel containing fluorine. Representation made using Ball and Stick software (Ozawa and Kang, 2004).

Représentation de la structure de l’apatite projetée sur le plan basal suivant l’axe c qui est aussi l’axe de symétrie sénaire. Notre le canal central contenant le fluor. Représentation faite avec le logiciel « Ball and Stick » (Ozawa and Kang, 2004).

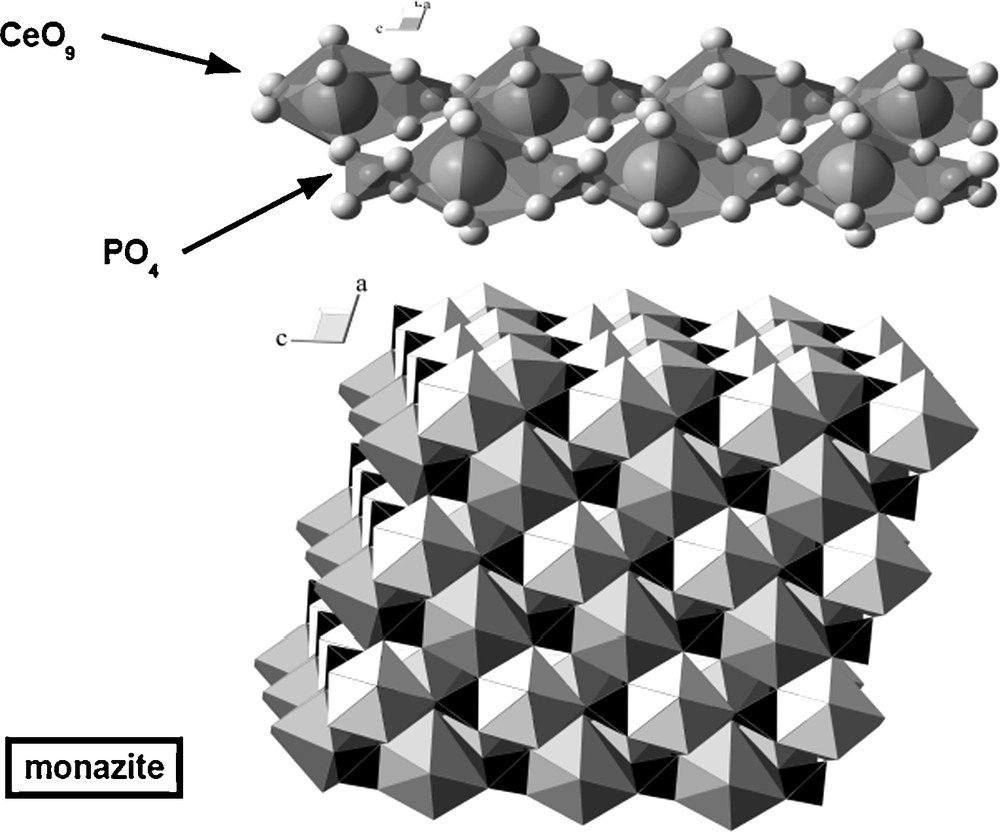

Monazite is the natural light-rare-earth orthophosphate (REEPO4, P21/m). Its structure can be viewed as a sheared zircon structure (Ni et al., 1995), with chains of alternating PO4 and REEO9 polyhedra (Fig. 2). In addition to REE3+, both trivalent (Am3+, Cm3+, Pu3+) and tetravalent (Np4+, U4+, Th4+) actinides (An3+ and An4+ respectively) can be incorporated in monazite by substitution with REE3+ for trivalent ions and by coupled substitution An4+ + Ca2+ = 2 REE3+, or An4+ + Si4+ = RE3+ + P5+ for tetravalent ions. Monazite is a common mineral in placers, and laboratory experiments confirm its low solubility and slow dissolution kinetics under various conditions (Oelkers and Poitrasson, 2002; Poitrasson et al., 2004; Pourtier et al., 2010). However, there is geological evidence that it can be dissolved in warm brines such as sedimentary bassins fluids (Hecht and Cuney, 2000; Mathieu et al., 2001). Despite it is a highly radioactive mineral (Slodowska-Curie, 1898), for an unknown reason, monazite is never metamict (Seydoux-Guillaume et al., 2004). As it is a general property of phosphate minerals (Meldrum et al., 1998), we can assume that, similarly to apatite, some kind of efficient self-healing process occurs over time. REE and phosphate are largely available raw materials and dense monazite-based ceramics can be readily obtained by various simple processes (Brégiroux et al., 2009; Montel et al., 2006).

Representation of monazite structure with individual chains (top) and general organisation (bottom).

Représentation de la structure de la monazite, avec les chaînes individuelles en haut et l’organisation générale en bas.

Thorium phosphate di-phosphate (TPD) has been proposed as waste-form for tetravalent actinides (Dacheux et al., 1999). The association of a highly insoluble cation (thorium) and of an insoluble anionic complex (phosphate) produces a waste-form displaying outstanding resistance to leaching (Thomas et al., 2000). It can be shaped as a dense ceramics by a simple sintering process (Dacheux et al., 2002). It is a layered structure, with alternating P-rich and Th-rich-layers (Fig. 3). Pu4+, U4+, or Np4+ are incorporated in large amount as a substitute for Th4+, but not Am3+ and Cm3+. The highly charged Th4+ cation is strongly bounded in the structure and despite a relatively open, layered structure, the leaching rates are very low. The weakness of TPD lies in the P2O7 group, which is present only in two rare minerals: wooldridgeite, Na2CaCu2(P2O7)2(H2O)10, and canaphite CaNa2(P2O7)4H2O. The weakness of P2O7 groups has been confirmed by experimental studies which showed that, in presence of Ca-rich fluids, TPD reacts to form of apatite and cheralite (CaTh-monazite) instead of TPD (Goffé et al., 2002).

Representation of thorium phosphate di-phosphate structure, project on the a–c plane along the b-axis. Note the layered structure with alternating Th- and P-layers and the presence of P2O7 (diphosphate groups).

Représentation de la structure du phosphate-diphosphate de thorium, projetée sur le plan a–c le long de l’axe b. Notez la structure lamellaire avec alternativement des couches riches en P et en Th et la présence de groupements diphosphates P2O7.

Zirconolite has been proposed as a waste form for actinides because it is a major actinide-bearing phase in Synroc (Ringwood et al., 1979). Synroc is a synthetic rocks made mainly of insoluble oxides (Zr, Ti), proposed as an alternative to borosilicate glasses as a universal waste-form (Ringwood, 1978). Synroc is made of zirconolite (30%), hollandite (30%), perovskite (20%), with minor Ti-oxide and metals. The nominal composition of zirconolite is CaZr2Ti2O7, and several polymorphs exist with Fm3m, Cmca, C2/c, or P312 space group. The structure chosen as waste-form is a layered C2/c zirconolite, with alternating TiO6 layers and Ca, Zr-rich layers (Fig. 4). Both trivalent and tetravalent actinides can be incorporated in zirconolite by substitution with Ca2+ and Zr4+, with coupled substitution of Al3+ or Fe3+ for Ti4+. Divalent Ca2+ is only moderately linked to the crystal structure, as shown by its preferential leaching (Leturcq et al., 2005). Zirconolite is resistant to leaching, because a protective Ti-Zr rich layer forms after few days in a way similar to the Si-rich layer which prevents the fast dissolution of borosilicate glasses. Zirconolite is an uncommon mineral but a reasonable amount of mineralogical data exists for it, showing that it becomes metamict by self-irradiation, but that metamict zirconolite is still resistant to fluids (Lumpkin, 2001).

Representation of the C2/c zirconolite structure on the a–c plane along the b-axis. Note the layered structure with alternating Ca + Zr rich layers and TiO6 + AlO6 rich layers.

Représentation de la structure de la zirconolite C2/c projetée sur le plan a–c le long de l’axe b. Notez l’alternance de couches riches en Ca + Zr et de couches d’octaèdres TiO6 + AlO6.

5.2 Waste-form for fission products

In the nuclear waste issue, three fission products deserve a special attention because of their abundance in spent fuel and long half-life: Technecium (99Tc, half-life T = 210 000 a, daughter element Ru), cesium, (135Cs, T = 2.3 Ma, 137Cs, T = 30 a, daughter-elements: Ba), and iodine (129I, T = 15.6 Ma, daughter-element Xe). For those products, which are β emitters, resistance to radiation damage is a minor problem. Mineralogy is useless for technecium, which does not naturally exist on Earth, and which does not even have an analog element.

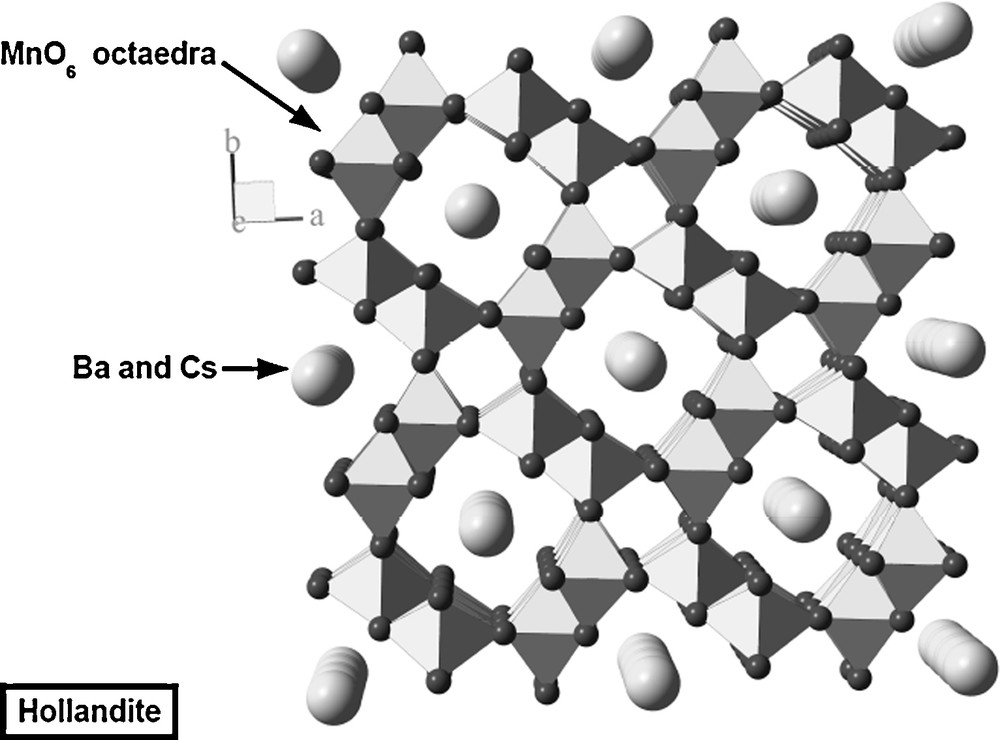

Cesium is a relatively common element, and about 20 minerals are known to hold a significant amount of cesium. Among them, only pollucite ((Cs,Na)2Al2Si4O12•(H2O), Ia3d), a zeolite of the analcime group, is not a rare mineral. As all zeolites, pollucite is an open structure, with cages, about 7 Å in diameter, able to accommodate large ions like Cs+. The most promising waste-form for cesium is based on hollandite, which is a barium mineral, and one of the main components of Synroc. Natural hollandite is a barium manganate (BaMn8O16, I4/m) with Cs (1.88 Å for coordination number XII) and Ba (1.61 Å) located in channels, about 5 Å in diameter, surrounded by MnO6 rings (Fig. 5). Ti, Fe or Al replaces Mn to a variable extent. The hollandite waste-form is a dense ceramics with modified composition BaCs0.28Fe0.82Al1.46Ti5.72016. Leaching tests show that this hollandite is chemically durable, but that Cs is released preferentially (Angéli et al., 2008).

Representation of the hollandite structure projected on the basal plane along the c-axis, 4-fold symmetry axis. Note the large channels containing Cs and Ba.

Représentation de la structure de la hollandite projetée sur le plan basal suivant l’axe c qui porte l’axe de symétrie quaternaire. Remarquez les vastes canaux contenant Cs et Ba.

Incorporation of iodine in a crystalline structure is a challenging issue, since, on Earth, this element occurs mainly in seawater. Few iodine-bearing minerals exist, iodargyrite (AgI) being the only noticeable one. Designing a crystalline waste-form for iodine relies on the presence of fluorine and chlorine in stable minerals such as micas, amphibole, or apatite. The structure proposed by Audubert et al. (1997) is an inflated apatite, in which the central channel is expanded up to a diameter compatible with iodine size. For that, phosphorus (0.17 Å in IV coordination) is replaced by vanadium (0.35 Å), and calcium (1.06 Å and 1.18 Å in VII and IX coordination respectively) is replaced by lead (1.23 Å and 1.35 Å in VII and IX coordination, respectively). Compared to nominal fluorapatite, the unit cell-parameters increase from a = 9.367 Å, c = 6.884 Å to a = 10.447 Å and c = 7.513 Å, allowing I− (2.20 Å) to be incorporated instead of F− (1.33 Å). Iodine is located in the channel, and is weakly bounded in the structure as shown by leaching test (Guy et al., 2002). This waste-form is actually derived from vanadinite Pb5(VO4)Cl which is a rather common mineral.

6 Conclusions and perspectives

Constraints from mineralogy, geochemistry, and geology must be taken into account for designing nuclear wastes because it is the only way to document directly the durability of a waste-form in a natural environment for geological times, using the concept of natural analog (Watson, 2006). For a given waste-form, some guess on the efficiency of a natural analog can be made from the amount of scientific literature available. A survey from the Georef database, yields: 23,000 publications for zircon, 11,400 for apatite (but only 115 for britholite), 4500 for monazite. For other minerals cited in the present paper, it ranges from 140 (zirconolite) to 350 (hollandite). From the available mineralogical and geochemical data, a mineralogist would certainly recommend monazite-based ceramics for minor actinides, hollandite for Cs, and I-vanadinite (which, for a mineralogist's point of view is a better name than I-Pb-V-apatite) for iodine, as safe crystalline waste forms.

New ideas will certainly emerge from further studies: chrichtonite (SrTi14Fe7O38, R3) and kosnarite (KZr2(PO4)3, R3c), may serve for designing new waste-forms, but are rare minerals (46 references for crichtonite, seven for kosnarite) for which further information is needed. A promising mineral is certainly florencite ((REE)Al3(PO4)2(OH)6, R3m,104 references) which is an alumino-phosphate with a flexible structure. It is stable under crustal conditions and acted as a trap for fissiogenic elements in the Oklo natural reactor (Dymkov et al., 1997; Janeczek and Ewing, 1996).

Acknowledgements

Georges Calas is warmly thanked for invitation to this special issue, as well as Anne-Magali Seydoux, Nicolas Dacheux, Michel Genet, Christophe Guy, and Jean-Eric Lartigue for fruitful discussion about nuclear waste management. The scientific review from Gordon Brown has been greatly appreciated.