1 Introduction

It is well acknowledged that the architecture of Asia results of the amalgamation of large continents such as Siberia, northern China, southern China, Tarim, Indochina, India, and several microcontinents: Lhasa, Qiangtang, Qaidam, etc. (e.g., Metcalfe, 2013; Fig. 1). The South China Block (SCB) is one of the most complex ones, as it underwent a long Phanerozoic evolution after its Neoproterozoic formation before 850 Ma during a collisional event that welded the Yangtze and Cathaysia Blocks (e.g., Charvet et al., 1996; Li et al., 2007a; Fig. 2). During the Early Paleozoic, the SCB was welded to the North China block along the Qinling–Dabie belt (e.g., Dong et al., 2011; Faure et al., 2008; Li et al., 2007b; Liu et al., 2013, Mattauer et al., 1985). Between the Late Ordovician and the Early Silurian, the closure of a Neoproterozoic Nanhua rift was responsible for the building of an intracontinental belt (e.g., Charvet et al., 2010; Faure et al., 2009; Wang and Li, 2003; Wang et al., 2013). From the Devonian to the Early Triassic, during ca. 170 Myr, the SCB behaved as a stable continent covered by a carbonate platform. However, in the Late Permian, the southwestern part of the SCB, in Yunnan and Guangxi, experienced a huge intraplate magmatism coeval with rifting, known as the Emeishan Large Igneous Province (Ali et al., 2005; Fig. 2).

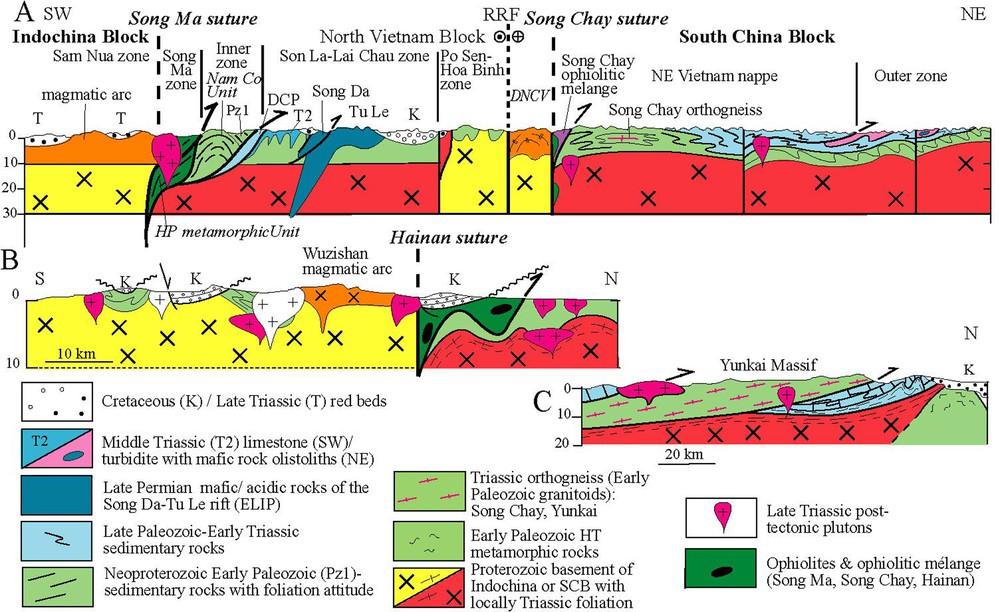

(Color online.) Schematic map of Central–Eastern Asia showing the main continental blocks, ophiolitic sutures, and faults. SCB: South China Block; D: Dabieshan; XFS: Xuefengshan; RRF: Red River Fault; LMS: Longmenshan. Pink lines denote the Triassic belts discussed in this paper. The diamond in Mindoro Island locates the Permian magmatic arc.

(Color online.) Tectonic map of the South China Block with emphasis on the Triassic events. The light pink area represents the Xuefengshan belt. RRF: Red River Fault; SCS: Song Chay suture; SMS: Song Ma suture; CLF: Chenzhou–Linwu fault; MXT: Main Xuefeng Thrust; JSF: Jiangshan–Shaoxing fault; DBF: Dien Bien Fu fault. NEV: NE Vietnam belt; DNCV: Day Nui Con Voi Triassic arc; DS: Darongshan pluton; SB: Shiwandashan Mesozoic basin. The cross-sections (Fig. 2A, B, C) are located.

The Triassic appears as the most important period for the tectonic development of the SCB. Since the recognition of a Norian unconformity and the definition of “Indosinian” movements in central Vietnam (Deprat, 1915; Fromaget, 1941), the term “Indosinian” has been ascribed to all Triassic tectonic and magmatic events throughout Asia, even if these features were geodynamically unrelated to Vietnamese ones. As numerous dates are now available, the Middle Triassic stratigraphic age will be preferred to “Indosinian”.

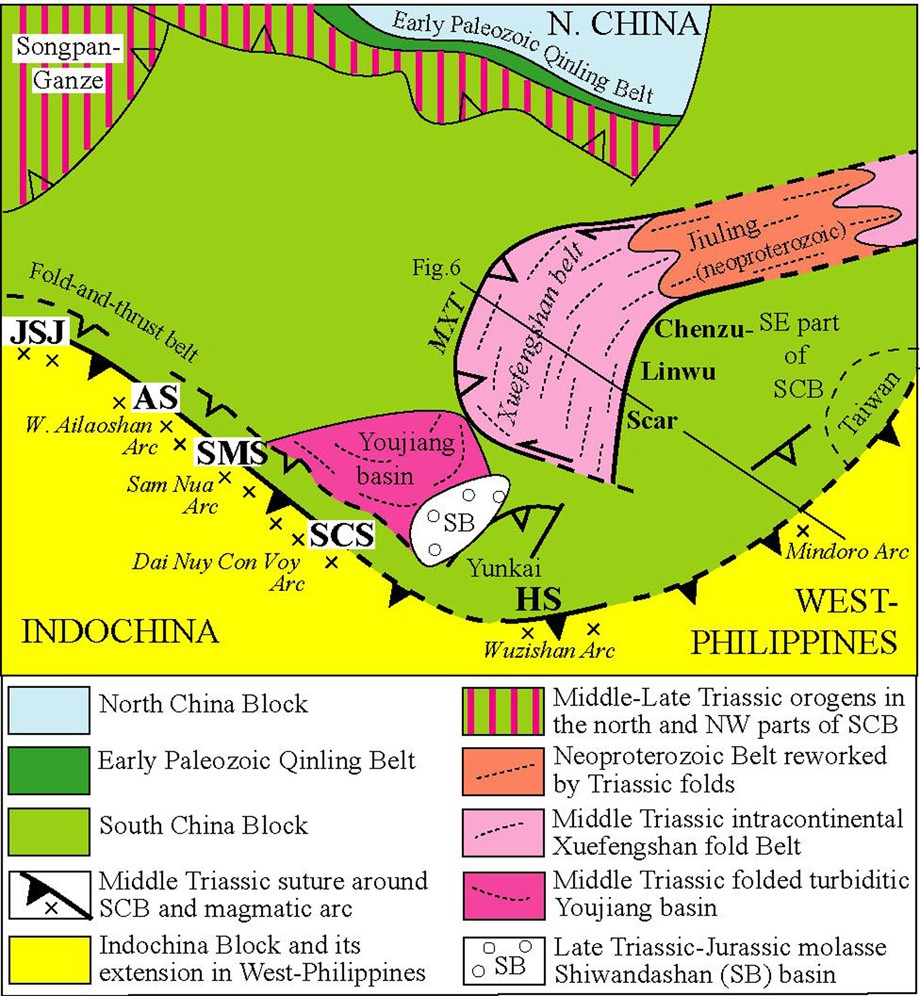

Triassic events are widespread all around the SCB (Fig. 2). South of the Early Paleozoic Qinling belt, Triassic top-to-the-south ductile shearing, HP and UHP metamorphism, and plutonism are documented (e.g., Faure et al., 2003, 2008; Hacker et al., 1998; Li et al., 2007b; Lin et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2013; Ratschbacher et al., 2003). To the northwest, in spite of an intense Cenozoic reworking, a southeast-directed Triassic thrusting is recognized in the Longmenshan belt (e.g., Burchfiel et al., 1995; Robert et al., 2010; Roger et al., 2008). The Jinshajiang, Ailaoshan, and North Vietnam belts represent the western and southwestern boundaries of the SCB. Furthermore, Middle Triassic events are responsible for the development of the Xuefengshan belt in the internal part of the SCB (Chu et al., 2012a,b; Wang et al., 2013; Fig. 2). The architecture and geodynamic evolution of these belts are still controversial, but it is widely accepted that the SCB belonged to the upper plate above a north (northeast or northwest)-dipping subduction zone (e.g., Li and Li, 2007; Wang et al., 2013).

The aim of this paper is to synthesize the Triassic tectonic features that develop along the southern margin of the SCB, and in its interior as well. Then a possible geodynamic interpretation, at variance to the present paradigm, will be discussed. The Triassic events of the northern part of the SCB, and the Jurassic and Cretaceous ones of the interior of the SCB will not be addressed here.

2 Triassic orogens of northern Vietnam

It is sometimes proposed that the Red River Fault (RRF) is the boundary between the SCB and Indochina. The RRF is a polyphase fault with Miocene sinistral ductile strike-slip (also referred to as the Ailaoshan–Red River shear zone), and a Plio-Quaternary dextral motion. The left-lateral ductile displacement that developed in response to the Indian collision was variously estimated from a few tens to several hundreds of kilometers (e.g., Leloup et al., 1995, 2006; Searle, 2006; Tapponnier et al., 1990). The strike-slip faulting accounts for the Cenozoic tectonics, but when dealing with the Triassic events, the RRF cannot be considered as a plate boundary, as ophiolites, subduction complexes, or HP metamorphic rocks are lacking. In contrast, two ophiolitic belts are recognized in NW and NE Vietnam on both sides of the RRF, along the Song Chay and Song Ma faults (Fig. 2; Faure et al., 2014; Lepvrier et al., 1997, 2008, 2011).

2.1 The NW Vietnam (Song Ma) belt

From southwest to northeast, several litho-tectonic zones are recognized (Figs. 2, 3A):

- • Permian–Early Triassic volcanic and sedimentary rocks of the Sam Nua zone, overlying an Early Paleozoic series, are interpreted as a magmatic arc (Liu et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2008a);

- • the Song Ma zone, formed by ultramafic, mafic rocks and deep marine sediments, represents an ophiolitic suture;

- • the Nam Co metamorphic rocks, developed at the expense of Neoproterozoic terrigenous series, and Paleozoic limestone and sandstone, correspond to the sedimentary cover of a continental basement deformed in a ductile fashion during the NE-ward thrusting of the Song Ma ophiolites;

- • farther north, folded unmetamorphosed successions of Devonian to Carboniferous limestone, Permian volcanics, Early Triassic clastics, and Middle Triassic carbonates represent the outer zone (Son La-Lai Chau zone) of this belt. There, Late Permian alkaline basalts and volcaniclastites form the Song Da rift. Although sometimes considered as ophiolites, these rocks, emplaced in an intraplate setting, belong to the Emeishan Large Igneous Province (Ali et al., 2005; Tran et al., 2008b; Tran and Vu, 2011). The Permian Tule acidic rocks are also relevant to this bimodal magmatism (Tran and Vu, 2011);

- • lastly, the Proterozoic basement, stratigraphically overlain by a Paleozoic sedimentary cover, is called the Posen–Hoabinh zone, which forms the deepest part of the NW Vietnam belt.

(Color online.) Crustal scale cross-sections of the Triassic belts. A. NW Vietnam–South China profile (simplified from Faure et al., 2014). B. Hainan profile. C. Yunkai profile.

The NW Vietnam belt exhibits a structural and metamorphic polarity decreasing from southwest to northeast. Late Triassic sandstone and conglomerate unconformably cover deformed rocks. Biotite and muscovite 40Ar/39Ar, zircon U/Pb, and monazite chemical U/Th/Pb ages around 245–230 Ma argue for a Middle Triassic age for the nappe architecture of the NW Vietnam belt (Lepvrier et al., 1997, 2008, Nakano et al., 2008, 2010).

2.2 The NE Vietnam (Song Chay) belt

Northeast of the RRF, another Triassic belt develops with the following southwest-to-northeast zonation (Faure et al., 2014; Lepvrier et al., 2011; Figs. 2, 3A):

- • the Dai Nuy Con Voi is a NW–SE-striking Cenozoic HT antiform developed from grauwacke and pelite hosting granodiorite, diorite and gabbro plutons of Permian–Triassic age (Gilley et al., 2003; Zelazniewicz et al., 2013). This zone is interpreted as a magmatic arc;

- • the Song Chay ophiolitic mélange is composed of serpentinites, mafic rocks, limestone, and chert blocks included in a terrigenous matrix of Triassic age;

- • The NE Vietnam nappe consists of Cambrian–Ordovician terrigenous rocks, and Devonian to Permian carbonates. Ordovician porphyritic granites (e.g., the Song Chay massif) are now changed into augengneiss. North- to northeast-verging folds and thrusts deform the entire lithological succession. Biotite–garnet–staurolite micaschist yields a monazite U–Th–Pb age at 246 ± 10 Ma (Faure et al., 2014);

- • the outer zone is a Paleozoic lithological succession similar to that of the NE Vietnam nappe covered by a thick Middle Triassic turbidite series with acidic lava flows and ashes. This formation includes olistoliths of alkaline basalt, gabbro, and limestone. Similar mafic rocks crop out in China where they intrude the Late Paleozoic limestone platform. They have been ascribed to the “Babu ophiolites” (Fig. 2, Cai and Zhang, 2009; Zhong, 2000), but their geological setting and geochemistry show that they are intraplate basalts corresponding to remote parts of the Emeishan Large Igneous Province (e.g., Zhou et al., 2006, see discussion in Faure et al., 2014). The NE Vietnam belt extends in China between Kunming and Nanning, the flat lying Late Paleozoic limestone platform is involved in north-directed folds and thrusts upon the Middle Triassic turbidite (Fig. 4C).

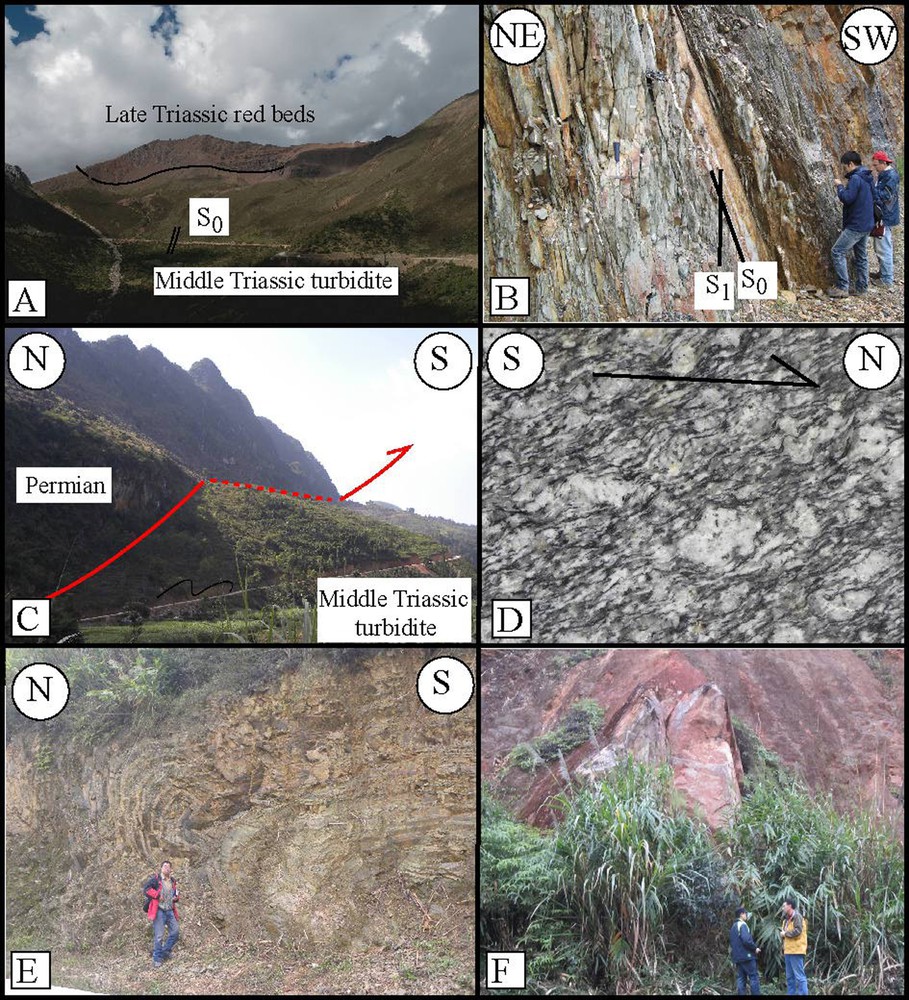

(Color online.) Field pictures of the Triassic belts. A. Late Triassic red beds unconformably overlying subvertical Middle Triassic turbidite (Jinshajiang, E. of Dexing). B. Bedding (S0) and cleavage (S1) relationships in Middle Triassic limestone indicate a NE-verging fold. A down-dip stretching lineation is observed in the S1 surface (Ailaoshan). C. Permian limestone overthrusting Middle Triassic turbidite (S. Guangxi). D. Early Paleozoic porphyritic granite deformed as orthogneiss with top-to-the-north shearing (Yunkai massif). E. North-verging fold in Devonian sandstone, in the footwall of the Yunkai thrust (Luoding). F. Carboniferous limestone olistolith in a Permian–Triassic siltite matrix (Hainan). Masquer

(Color online.) Field pictures of the Triassic belts. A. Late Triassic red beds unconformably overlying subvertical Middle Triassic turbidite (Jinshajiang, E. of Dexing). B. Bedding (S0) and cleavage (S1) relationships in Middle Triassic limestone indicate a NE-verging fold. A down-dip ... Lire la suite

In summary, both the NW and SE Vietnam belts are collisional orogens formed by a southwestward subduction of oceanic, then continental lithosphere. Due to their lithological, structural, and chronological similarities, the two belts have been interpreted as the result of a duplication of a single Triassic orogen by the Cenozoic left-lateral strike-slip shearing of the Ailaoshan–Red River shear zone (Faure et al., 2014).

3 The western extension of the North Vietnam orogens

3.1 The Ailaoshan belt

This NW–SE 500-km-long belt (Fig. 2) is subdivided into several narrow stripes by belt-parallel strike-slip faults. In spite of the intense Cenozoic shearing (e.g., Leloup et al., 1995), the Ailaoshan is commonly acknowledged as a Triassic suture zone between the SCB and the Indochina–Simao block, but structural details and subduction polarity are disputed (e.g., Fan et al., 2010; Jian et al., 2009a,b; Lai et al., 2014a,b; Wang et al., 2013; Zhong, 2000). From southwest to northeast, four litho-tectonic zones ascribed to the Triassic orogen are recognized (Fig. 2):

- • the Western Ailaoshan, characterized by volcanic and sedimentary rocks, is unconformably overlain by Late Triassic red conglomerate and sandstone. Basalt and andesite, dated to between 287 and 265 Ma, were originated in a magmatic arc installed upon a Silurian–Devonian terrigenous series (Fan et al., 2010; Jian et al., 2009a);

- • the Central Ailaoshan contains serpentinite, gabbro, dolerite, plagiogranite, basalt, chert, and limestone blocks enclosed into a terrigenous matrix (Lai et al., 2014b). Zircon from plagiogranite yields U–Pb ages at 383–376 Ma, 365 Ma, and 328 Ma interpreted crystallization age of ophiolitic protoliths (Jian et al., 2009b; Lai et al., 2014b). This domain represents an ophiolitic mélange, but the age of the matrix is unknown;

- • the eastern Ailaoshan consists of gneiss, micachists, amphibolites, marbles, and migmatites that form a Paleoproterozoic basement, partly reworked during the Cenozoic (Lin et al., 2012). Middle Triassic carbonate covers the crystalline basement;

- • the Jinping area exposes Late Permian mafic lava, pillow breccia, agglomerate, and volcaniclastites (Wang et al., 2007a). Furthermore, felsic volcanites dated to ca. 246 Ma result from syn- to late-collisional crustal melting (Lai et al., 2014a).

A steeply dipping foliation and a subhorizontal lineation are the main ductile structures developed during the Cenozoic shearing as they involve the Late Triassic rocks. Nevertheless, a steeply dipping stretching lineation with top-to-the northeast sense of shear and northeast-verging folds are also observed (Fig. 4B). These structures, incompatible with the strike-slip event, and not observed in the Late Triassic or younger rocks, are of Middle Triassic age.

Thus, in spite of the Tertiary overprint, the Ailaoshan belt is comparable with the North Vietnam belts. Namely, the western, central, and eastern Ailaoshan zones are equivalent to the Sam Nua, Song Ma, Posen-Hoabinh zones, respectively. The Sonla–Laichau zone pinches out in the Ailaoshan, except in the Jinping area, where magmatic rocks are similar to those in the Song Da rift.

3.2 The termination of the NE Vietnam belt

The NE Vietnam belt abruptly ends in China (Fig. 2). The Dai Nuy Con Voi metamorphics are surrounded by Permian–Early Triassic volcanites and grauwackes corresponding to the magmatic arc, but ophiolites are not exposed. Folded and thrusted Paleozoic rocks are equivalent to those of the NE Vietnam nappe. To the north, Middle Triassic turbidites of the Youjiang basin involved in north-verging folds correlate with the outer zone of NE Vietnam.

3.3 The Jinshajiang belt

At the edge of the Tibet plateau, the Triassic Jinshajiang orogen is documented by the Late Triassic unconformity overlying a folded Middle Triassic ophiolitic mélange with basalt, chert, and limestone blocks (Fig. 4A, Wang et al., 2000; Zhong, 2000). This mélange overthrusts to the east the Late Paleozoic–Triassic carbonate platform of the SCB. To the west, a Permian–Early Triassic magmatic arc argues for a west-directed subduction. The bimodal magmatism at 245–237 Ma is interpreted as syn- to post-collisional (Zi et al., 2012). The Jianshajiang Belt exhibits lithological and structural features similar to those of the Ailaoshan and North Vietnam orogens.

4 The eastern extension of the North Vietnam orogens

4.1 The Yunkai Massif

In Guangxi, the Late Triassic–Jurassic red sandstone of the Shiwandashan basin (SB in Fig. 2) is a post-orogenic molasse with respect to the Triassic orogeny (e.g., Hu et al., 2014). The Yunkai massif consists of Early Paleozoic HT metamorphics, migmatites, and Triassic granites tectonically surrounded by weakly metamorphosed Devonian–Carboniferous sedimentary rocks (e.g., Lin et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2007b). The metamorphic rocks belong to the Early Paleozoic orogen of SE China, but were intensely reworked by the Triassic events. The flat-lying foliation and NE–SW stretching lineation, associated with a top-to-the-northeast ductile shearing, developed at ca. 250–240 Ma. During this event, the Early Paleozoic granites were changed to orthogneiss (Fig. 4D). The Yunkai massif is a 100km-scale basement nappe that overthrusts northward onto the Late Paleozoic sedimentary rocks of the SCB (Figs. 3C, 4E). As ophiolites are lacking there, the eastward extension of the Song Chay suture should be searched more to the south in Hainan Island (Fig. 2).

4.2 Triassic tectonics in Hainan Island

The tectonic evolution of Hainan Island remains controversial. The Cretaceous and younger extensional events are not considered here. Late Triassic plutons seal the main ductile deformation (Fig. 3B). North-verging folds and thrusts deform the Early Paleozoic series and the underlying Proterozoic basement. Granodiorites and biotite granite with calcalkaline geochemical signatures, and yielding zircons SHRIMP U–Pb ages at 267 ± 3 Ma and 263 ± 3 Ma by SHRIMP method, are interpreted as the “Wuzishan magmatic arc” (Li et al., 2006). North of this arc, a Late Permian–Early Triassic terrigenous series including Carboniferous gabbro, basalt, siliceous rocks and limestone is interpreted as a mélange (Fig. 4F; Li et al., 2002). This formation is deformed in a ductile fashion with top-to-the-north kinematics dated at ca. 250–240 Ma by the 40Ar/39Ar method on micas (Zhang et al., 2011). In spite of a still limited knowledge, the Hainan Island appears as a suitable site for the eastern extension of the Song Chay suture.

5 Triassic intracontinental tectonics in the eastern SCB

5.1 The Xuefengshan belt

Middle Triassic tectonics is not limited to the SCB margins. In the central SCB (eastern Hunan and Guangxi), the Xuefengshan Belt is a NNE–SSW-striking 700-km-long belt dominated by NW-directed thrusts and folds. Southeast-verging folds are interpreted as secondary back-folds (Chu et al., 2012a; Fig. 5). A ductile decollement layer, intruded by Late Triassic plutons dated to 225–215 Ma by the SIMS U–Pb method on zircon (Chu et al., 2012c), exhibits a NW–SE-striking stretching lineation, and top-to-the-NW sense of shear (Chu et al., 2012b). This 500-km-wide fold-and-thrust belt involves the entire Neoproterozoic to Early Triassic sedimentary pile to the west of the Chenzhou–Linwu fault (CLF in Fig. 2). This fault, devoid of ophiolites and subduction mélange, is not a suture zone, but an intracontinental “scar”. In order to balance the ca. 300 km of shortening experienced by the sedimentary rocks overlying the decollement layer, a SE-ward continental subduction of the same amount must have taken place in the crystalline basement of the western part of the SCB (Chu et al., 2012a).

(Color online.) Crustal scale cross-section of the intracontinental Xuefengshan belt (modified from Chu et al., 2012a). Folding and shearing, pre-dated by the emplacement of Late Triassic plutons accommodated the SE-ward underthrusting of the western part of the SCB below its eastern part. S1, S2, S3 are the cleavage planes related to the Triassic deformation phases (cf. Chu et al., 2012a for detail).

5.2 Coastal and eastern SE China

East–west-striking folds develop south of the Jiangshan–Shaoxing Fault (Fig. 2). The Late Triassic regional unconformity argues for a Middle Triassic event (Shu et al., 2008). As documented in the Jiuling area (Chu and Lin, 2014), upright folds are lateral ramps related to the Xuefengshan belt. The east–west-elongated Wugongshan dome located immediately south of the Jiangshan–Shaoxing fault (Fig. 2; Faure et al., 1996) might have also developed during the reactivation of this Neoproterozoic suture. The Triassic ductile deformation is probably underestimated in the eastern part of the SCB (Wang et al., 2014).

In the coastal area of SE China, widespread Jurassic and Cretaceous granites and volcanites hide older formations. West of Fuzhou, Middle Triassic rocks deformed by north-verging recumbent folds and covered by a Late Triassic unconformity indicate that the SE China coastal area also experienced a Middle Triassic deformation (Zhu et al., 1998).

6 Discussion of the Triassic orogens

A north-directed Triassic oceanic subduction, below the SCB, is often suggested (e.g., Li and Li, 2007; Zhou and Li, 2000). This view is based on the assumption that the active continental margin of the SCB existed since the Middle Permian (Li et al., 2006, 2012). Indeed, an active margin setting has been documented for the Cretaceous, but the geochemistry of the Jurassic magmatism supports rather an intraplate setting (Chen et al., 2008). As in Vietnam, in Hainan, the relative positions of the mélange and arc argue for a south-directed subduction. In SE China, most of the Late Triassic plutons are S-type due to the melting of Proterozoic sediments, and a small amount of A-type plutons also exists (e.g., Chen et al., 2011; Li et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2012). The tectonic setting of these plutons is not documented. Furthermore, their emplacement ages do not clearly show a NW-to-SE polarity that might be related to a north-directed subduction.

Therefore, an alternative interpretation is tentatively proposed here. The NW-directed shearing and 300-km shortening recorded by the sedimentary series of the Xuefengshan Belt are balanced by the same amount of continental subduction. This means that during the Triassic, the SE China lithosphere was underlain by a slab corresponding to the SE-ward subducted lithosphere of the western part of the SCB (Figs. 6 and 7).

(Color online.) Lithosphere scale interpretative cross-section from the Xuefengshan to the southeastern coast of the SCB, depicting the Triassic deformation. The Early Paleozoic and Cretaceous events have been omitted for clarity. The Triassic geodynamics of the southern part of the SCB are interpreted as the consequence of intracontinental subduction in the Xuefengshan and collision of the SCB with a continental block equivalent to Indochina presently hidden below the South China Sea. The evidence of a magmatic arc is documented in Hainan Island and in western Philippines. Masquer

(Color online.) Lithosphere scale interpretative cross-section from the Xuefengshan to the southeastern coast of the SCB, depicting the Triassic deformation. The Early Paleozoic and Cretaceous events have been omitted for clarity. The Triassic geodynamics of the southern part of the ... Lire la suite

(Color online.) Schematic map showing the main Triassic tectonic features of the southern margin of the SCB. At variance with the previous interpretations, this cartoon emphasizes the southward continental subduction of the SCB below the Indochina Block and its eastward extension in western Philippines that was located south of the SCB before the opening of the South China Sea. Collision was preceded by oceanic subduction that gave rise to several magmatic arcs, namely: W. Ailaoshan, Sam Nua, Dai Nuy Con Voi, Wuzishan, Mindoro. JSJ: Jinshajiang suture; AS: Ailaoshan suture; SMS: Song Ma suture; SCS: Song Chay suture; HS: Hainan suture. Terrigenous deposits of the Shiwandashan basin (SB) unconformably cover the folds and thrusts of the Middle Triassic Youjiang basin. The intracontinental Xuefengshan Belt developed in response to the southeastward continental subduction of the basement of the SCB. MXT: Main Xuefengshan Thrust. The dotted lines represent the fold axes. The Triassic east–west-to-NE–SW-striking folding developed in the Neoproterozoic Jiuling Massif corresponds to a dextral ramp of the Xuefengshan belt. The Triassic plutons have been omitted for clarity. Masquer

(Color online.) Schematic map showing the main Triassic tectonic features of the southern margin of the SCB. At variance with the previous interpretations, this cartoon emphasizes the southward continental subduction of the SCB below the Indochina Block and its eastward ... Lire la suite

Along the SE China coast, evidence for a Triassic subduction is not documented. Assuming an eastward extension of the Jinshajiang–Ailaoshan–North Vietnam–Hainan belt would imply that the SCB represents the lower plate. Such a polarity may account for the thrusting sense observed in Yunkai, Hainan, and SE China. The Triassic peraluminous plutons (e.g., Darongshan granite, DS in Fig. 2) emplaced in the footwall of the major thrust zones during deep-seated thrusting coeval with melting. Moreover, Permian arc magmatism is documented in Mindoro Island of western Philippines (Fig. 1; Knittel et al., 2010). Considering the Cenozoic opening of the South China Sea, this arc represents the eastern extension of the Wuzishan arc of Hainan. Triassic ophiolites and tectonics are unknown in the Philippines, but the Tailuko belt of Taiwan that exposes the deepest rocks of the island yields garnet–chloritoid–kyanite–staurolite micaschist with metamorphic zircon dated to 200 ± 22 Ma (Yu et al., 2009; Fig. 2). Furthermore, HP metamorphic rocks crop out in the southern Ryukyu Islands (Fig. 2). In these mafic schists, phengite and barroisite are dated to 225 ± 5 Ma and 237 ± 6 Ma, respectively (Faure et al., 1988). One possibility is to relate these features to the Triassic orogeny of the SCB.

In conclusion, the Triassic belts that wrap around the SCB southern margin from southwest to southeast exhibit lithostratigraphic, structural, and chronological resemblances that allow us to infer that a single belt developed in response to the subduction and collision of the SCB below the Qiangtang–Indochina block. Such a south-directed subduction was coeval with the intra-continental subduction responsible for the development of the structures in SE China. Work in progress aims at testing this new interpretation.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to I. Manighetti and B. Mercier de Lépinay for their invitation to pay a tribute to J.-F. Stéphan who devoted his scientific activity to the understanding of orogenic processes, and particularly to the geodynamics of SE Asia. The constructive comments of H. Leloup, B. Mercier de Lépinay and I. Manighetti are acknowledged. This work has been supported by NSFC grants 41225009 and 41472193 and a Major State Special Research on Petroleum project 2011ZX05008-001.