1. Introduction

Rock masses and veins that reveal porphyritic texture and a microcrystalline groundmass are generally known as porphyries. Originally, the word “porphyry” was used to describe rocks with a red aphanitic paste, similar to jasper, that enveloped quartz and feldspar phenocrysts [American Geological Institute 1962]. Nowadays, the term refers to hypabyssal or subvolcanic rocks revealing either felsic or mafic phenocrysts and a fine-grained groundmass. However, at present, porphyry composition is still a matter of debate. While the majority of the geoscientific community believes that porphyries are mainly felsic [e.g. Vaasjoki et al. 1991, Förster et al. 2007, Wang et al. 2020], some authors argue that their mineral assemblages can be either felsic or mafic [e.g. Damian et al. 2009, Jokela 2020]. For purposes of clarification, the terminology adopted in this paper always refers to felsic hypabyssal rocks whose mineralogy is granitic or rhyolitic and whose texture is subvolcanic to volcanic.

In both Portugal and Spain, the areas belonging to the Central Iberian Zone are rich in hypabyssal veins of felsic (granitic or rhyolitic porphyries) and mafic (lamprophyres and dolerites) composition. However, even though the existence of these lithologies has been recognized since the 20th century [e.g. Alibert 1985], extensive studies of subvolcanic rocks in northern Portugal have not begun until recently [e.g. Oliveira et al. 2018, 2019a,b, 2020]. As such, the current state of knowledge about porphyries and mafic dykes in the portuguese section of the Central Iberian Zone (CIZ) is extremely poor. Even though there are several papers concerning the occurrence, petrography, geochemistry, and geochronology of mafic veins in the Spanish CIZ [e.g. Alibert 1985, Bea et al. 1999, Bonin 2004, Orejana et al. 2008], detailed studies regarding felsic porphyries in this section of the largest geotectonic/tectonostratigraphic Iberian zone are relatively scarce [e.g. Corretgé and Suárez 1994]. In their work, Corretgé and Suárez [1994] studied the petrography, microstructures, geochemistry, and mineral chemistry of a garnet and cordierite-bearing granitic porphyry dyke containing rapakivi feldspars in the Cabeza de Araya batholith (Central Spain). These authors suggested that the mineral assemblage of the porphyry resulted from nearly isothermal decompression during fast magma ascent. The rapid kinematics would also be responsible for microstructures such as kinks in biotite and corrosion gulfs in early feldspar crystals, the development of late-stage generations of biotite and cordierite, and the albite and potassium feldspar rims around ovoid, earlier alkali-feldspar crystals.

Two of the most geographically expressive porphyry outcrops in northern Portugal are found in the Vila Pouca de Aguiar and Vila Nova de Foz Côa regions. Besides being regionally significant, these porphyry veins are reasonably well preserved, enabling a proper petrographic and geochemical study. This paper reports the petrography, texture, microstructures, whole-rock geochemistry, and Sm–Nd isotope geochemistry of the Vila Pouca de Aguiar (VPA) and Vila Nova de Foz Côa (VNFC) porphyries. The main goal of this research is to improve the state of knowledge concerning the petrogenesis of the felsic vein magmatism in the Central Iberian Zone, with particular emphasis on the portuguese territory.

2. Geological setting

The study areas are located in northern Portugal, in the Iberian Massif, and belong to the Central Iberian Zone (CIZ) (Figure 1). The main geological and geodynamic features of the CIZ were strongly conditioned by the Variscan orogeny. According to Martínez Catalán et al. [2009], the Variscan cycle resulted from the collision between the continental masses of Laurentia and Gondwana. The collisional event happened around 380 Ma (Upper Devonian to Lower Carboniferous) and its effects ceased during Lower Permian times (around 280 Ma).

Location of the study areas (2: Vila Pouca de Aguiar; 3: Vila Nova de Foz Côa) in the Iberian Massif setting [adapted from Dias et al. 2016]. Geotectonic zones: WALZ—West Asturian-Leonese Zone; CZ—Cantabrian Zone; CIZ—Central Iberian Zone; GTMZ—Galicia-Trás-os-Montes Zone; OMZ—Ossa-Morena Zone; SPZ—South Portuguese Zone.

In NW Portugal, the Variscan orogeny is associated with three main ductile deformation phases (D1, D2, and D3) and one brittle post-tectonic D4 phase [Dias and Ribeiro 1995, Martins et al. 2014]. When the crustal thickening and shortening ceased, the regional tectonics shifted to a regime of subvertical transcurrent shears that characterize phase D3 [Diaset al. 2010]. The latter generated vertical ductile shear zones in lower structural levels and conjugated brittle fracture systems, with NNE–SSW and NNW–SSE trends, in the upper levels [Marques et al. 2002]. During phase D3, the regional extension compensated the thickening, causing lithospheric decompression that led to a thermal peak. The decompression triggered anatexis on different crustal levels, which resulted in the generation of several anatectic granite melts displaying a remarkably high compositional variability [Diaset al. 2010, Martins et al. 2009, 2013, Ribeiroet al. 2019]. Since the emplacement of the Variscan granites is mainly related to phase D3, a classification, based on geochronology, has been proposed to distinguish the granites: syn-D3 (ca. 320–312 Ma), late-D3 (ca. 312–305 Ma), late to post-D3 (ca. 300 Ma), and post-D3 granites (ca. 299–290 Ma) [Ferreiraet al. 1987, Azevedo and Valle Aguado 2013, Martins et al. 2014, Cruz 2020].

The Vila Pouca de Aguiar (VPA) region is approximately located 117 km to the northeast of Porto, in northern Portugal. Two porphyries of granitic/rhyolitic composition intrude into the post-tectonic (i.e., post-D3) VPA pluton, whose main facies are the Vila Pouca de Aguiar and Pedras Salgadas granites. The VPA granite is biotite-rich, medium to coarse-grained, and porphyritic, while the PS (Pedras Salgadas) facies is biotite and muscovite-rich, medium-grained, and porphyritic as well. According to Martins et al. [2009], U–Pb zircon analyses yield an emplacement age of 299 ± 3 Ma. The pluton is a laccolith, and its emplacement was controlled by the sinistral Penacova-Régua-Verín strike-slip fault [Sant’Ovaia et al. 2000]. The porphyries are located on the northeastern section of the pluton and have been named the Loivos vein, at west, and Póvoa de Agrações vein (PA), at east [Oliveira et al. 2019a,b, 2020]. Both structures are N–S trending, about 45 m wide, and ca. 7 km long (Figure 2). Field studies have shown that the western vein only intersects the VPA granite, and always reveals sharp contacts. However, in one location, a microgranite was detected in the contact between the porphyry and host granite. On the other hand, the PA vein intrudes both the Vila Pouca de Aguiar granite and quartzphyllites of the Santa Maria de Émeres Unit [Silurian age; Sant’Ovaiaet al. 2011], which belongs to the parautochthonous of the Galicia-Trás-os-Montes Zone (GTMZ). Near the contact between the eastern porphyry and the GTMZ quartzphyllites, there is a very fine-grained, compact, and banded lithology in close association.

Geological Map of the Vila Pouca de Aguiar region [modified from Noronha et al. 1998]. The Curros, Cubo, and Santa Maria de Émeres Units, as well as the Rancho Subunit, constitute different domains of the GTMZ, all of which are composed of Paleozoic metasediments. All regional granites are Variscan.

Among the various porphyry outcrops in northern Portugal, the vein located in the Vila Nova de Foz Côa (VNFC) region stands out as a special case. The VNFC porphyry is situated about 125 km to the east of Porto, approximately 21.1 km long, 10–20 m wide, and E–W trending (in general) with steep plunges to the north. The vein is hosted in a WSW–ENE ductile shear zone and mainly intrudes into several regional Variscan granites, which are mostly muscovite and biotite-rich, as well as syn-tectonic (syn-D3) [Ferreira et al. 2020]. However, the porphyry also cuts metasedimentary units of the Schist–Greywacke Complex (Figure 3). According to Silva and Ribeiro [1991], the VNFC vein is cut by multiple strike-slip sinistral faults such as the Vilariça, Portela, and Barril faults (NNE–SSW trending), as well as the Seixo fault (WSW–ENE trending). The porphyry outcrops throughout the entire extent of the eastern block of the Vilariça fault, where its local trend shifts between ENE–WSW and WNW–ESE. On the other hand, in the western block, there are three small, ENE–WSW trending dykes of the granitic vein (10–30 m long), which most likely represent an offset of the porphyry created by the Vilariça fault [Oliveira et al. 2018].

Geological Map of the Vila Nova de Foz Côa region [modified from Silvaet al. 1990]. All of the illustrated regional granites are Variscan. The Desejosa, Pinhão, and Rio Pinhão formations represent different metasedimentary units of the Schist–Greywacke Complex. Cenozoic and Quaternary formations are represented by Neogene (conglomerates and arkoses), Plio-Pleistocene (gravel beds), and Holocene (slope deposits, colluvium, and alluvium) cover deposits. The bold italic letters symbolize the most important regional faults: A—Vilariça; B—Portela; C—Barril; D—Seixo.

3. Methods

3.1. Whole-rock geochemistry

A total of 16 crushed-rock samples (<63 μm) were analyzed for whole-rock geochemical studies. The sample set includes four samples of the Loivos porphyry, four of the PA vein, two samples of the compact lithology that appears in the contact between the Póvoa de Agrações porphyry and GTMZ quartzphyllites, and six samples of the VNFC vein. Sampling site locations are indicated in Figures 2 and 3 (exact coordinates are given in Appendix A). The collected field samples were reasonably fresh and unweathered. Each sample weighed approximately 10 kg.

Whole-rock analyses were performed at the Activation Laboratories in Ancaster (Ontario, Canada). The samples were subjected to lithium metaborate/tetraborate fusion, subsequent Inductively Coupled Plasma and Mass Spectrometry (ICP/MS) analysis, dilution, and reanalysis by a Perkin Elmer Sciex ELAN 6000, 6100, or 9000 ICP/MS equipment. Three blanks and five controls (three before sample group and two after) are analyzed per group of samples. Duplicates are fused and analyzed for every 15 samples. The instrument is recalibrated every 40 samples. For each sample, mass analysis is required as an additional quality control technique, and totals vary between 98.5% and 101%. The detection limits associated with these analyses are the following: 0.01% for major elements; 0.001% for minor elements; and 0.01 to 30 ppm for trace elements.

Sodium peroxide fusion was used to determine lithium contents. Rubidium was also analyzed since the previous technique proved to be inadequate in determining accurate contents of this element in various samples. The procedure requires an initial sodium peroxide fusion followed by acid dissolution. Samples are then analyzed by the Perkin Elmer Sciex ELAN 6000, 6100, or 9000 ICP/MS equipment. A fused blank is run in triplicate for every 22 samples. Fused controls and standards are run after the 22 samples. Fused duplicates are run for every 10 samples. The instrument is recalibrated for every 44 samples. The detection limits of this method, for both lithium and rubidium, are 0.001%.

The studied samples were also fused with a combination of lithium metaborate and lithium tetraborate, in an induction furnace to release fluoride ions from the sample matrix, to determine fluorine contents. Afterward, the fuseate was dissolved in dilute nitric acid, the solution complexed, and the ionic strength adjusted with an ammonium citrate buffer. A fluoride-ion electrode was immersed in the final solution to measure the fluoride-ion activity directly. The detection limit is 0.01%.

3.2. Sm–Nd isotope geochemistry

Isotope analyses concerning the Sm–Nd system were executed in Bilbao, Spain, at the Laboratories of General Research Service for Geochronology and Isotopic Geochemistry of the University of the Basque Country (SGIKER–UPV/EHU). The selected samples were analyzed by ID–MC–ICP-MS (Isotope Dilution–Multi-collector–Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry). About 0.050–0.200 g of each whole-rock sample was weighed and mixed with a proportional amount of an enriched 149Sm–150Nd tracer. The sample-tracer mixtures were digested after a tri-acid attack (HF–HNO3–HClO4) following the procedures of Pin and Santos Zalduegui [1997]. These procedures were also used for samarium and neodymium purification. For the mass spectrometry, pure Sm and Nd fractions were separately dissolved in 2 mL of 0.32N HNO3 and diluted to final concentrations of about 30 ng Sm/g and 20 ng Nd/g solutions. The certified reference material JNdi-1 was analyzed to verify the accuracy and reproducibility of the method. The average 143Nd∕144Nd ratio of 2 determinations in this standard during the same analytical session was 0.512091, with 2𝜎 = 0.000009𝜎. The precision in the determination of the 147Sm∕144Nd ratio by isotope dilution is typically better than 0.2%. The calculation of the 𝜀Ndi parameter was based on the decay constant of Lugmair and Marti [1978] for isotope 147Sm (𝜆 = 6.54 × 10−12 y−1), as well as the CHUR 143Nd∕144Nd and 147Sm∕144Nd ratios of Jacobsen and Wasserburg [1984].

Petrographic photographs and microphotographs of the VPA and VNFC porphyries: (a) hand sample of the Loivos porphyry (sample 61-2); (b) variability of the groundmass granularity (sample 61-1C); (c) embayment on a quartz microphenocryst (sample 61-D); (d) granophyric texture (sample 61-2A); (e) antirapakivi feldspars (sample VNFC2A); (f) rapakivi feldspars (sample 61-1C); (g) kinked primary muscovite microphenocryst (sample 61-1C); (h) pinitization: pseudomorphs of white micas after cordierite (sample 61-2). Legend: Qz—quartz; Kfs—potassium feldspar; Pl—plagioclase; Bt—biotite; Ms—muscovite; Crd—cordierite; Kln—kaolinite; Sc—sericite; Chl—chlorite. All microphotographs were taken in CPL.

4. Results

4.1. Petrography and SEM-EDS

A detailed and thorough petrographic study of the VPA and VNFC porphyries was carried out on a macroscopic and microscopic scale. During the field studies, local magnetic susceptibilities (Km) were measured using a portable magnetic susceptibility meter, model Terraplus KT-10.

Hand specimen of the Loivos vein exhibit either an indistinguishable grain size or a very fine granularity in the groundmass, which is light gray or light beige (Figure 4a). The granularity of the PA and VNFC porphyries is generally finer and mostly indiscernible to the naked eye, while the groundmasses are respectively greenish or pinkish and light gray to light beige. All samples of the PA vein display a very fine banding and sample VNFC2A of the E–W trending porphyry shows feldspar phenocrysts that seemingly follow the local vein trend (N130° to 145° E). Despite the previous observations, overall, none of the porphyries reveals any sort of anisotropy regarding the orientation of the composing minerals. All veins exhibit abundant phenocrysts, mostly 0.1 to 2.5 cm long, composed of quartz, feldspars, cordierite, and biotite. Several mafic phenocrysts are altered, presenting orange or brownish-colored rims made of Fe oxides. However, in the Loivos porphyry, alteration is more pronounced in the groundmass due to rubefaction. Based on the microscopic studies, all veins display two holocrystalline textures whose differences mostly concern granularity (Figure 4b). In the Loivos porphyry, both textural varieties are aphanitic and porphyritic, while in PA and VNFC, the coarser facies is aphanitic (phenocryst-rich) and the finer facies is aphyric (phenocryst-poor). The groundmasses are mainly composed of quartz, K-feldspar, and muscovite. Apatite, ilmenite, zircon, and monazite are less common but present in all veins. The Loivos and VNFC porphyries also have late-stage chlorite, as well as secondary minerals such as brookite/anatase, hematite, and goethite. Allanite and rare Fe–Mn–Al/Na phosphates (childrenite, scorzalite (?), and gayite (?)) were exclusively observed in the PA vein. Compositionally, the VPA and VNFC porphyries are identical to syenogranites or alkali-feldspar granites. The contacts between the VPA veins and respective spatially associated lithologies (i.e., microgranite for Loivos and compact lithology for PA) are gradual. In both cases, there are strong similarities regarding texture, color, and granularity.

Quartz is the most abundant mineral phase. It occurs either in fine anhedral grains at the groundmass level or in phenocrysts and microphenocrysts. The latter are dominantly anhedral (Loivos porphyry) or subhedral to euhedral (PA and VNFC veins). Grain boundaries are mostly linear or curved. Quartz inclusions in some K-feldspar phenocrysts define lineaments which circumscribe to the shape of the host mineral. In the finer portions of all porphyries, groundmass quartz occasionally reveals a “drop-like” texture. In the PA and VNFC veins, quartz phenocrysts display multiple fractures, which are normally filled either by groundmass grains or Fe oxides. Concerning textures and microstructures, quartz phenocrysts present common embayments (Figure 4c), undulatory extinction, and occasional polygranular aggregates or subgrains. In the boundaries with K-feldspar phenocrysts or microphenocrysts, quartz sometimes reveals granophyric texture (this feature was only observed in Loivos) (Figure 4d).

Potassium feldspar occurs in fine, mostly anhedral groundmass grains, or in phenocrysts and (scarce) microphenocrysts of tabular habit and subhedral to euhedral shape. In all porphyries, Karlsbad twinning is more common than the cross-hatched one. Occasionally, the twinnings are deformed. Perthites are venule, sector, band, or bar type. Together with plagioclase (and sometimes quartz), K-feldspar microphenocrysts form agglomerates in glomeroporphyritic texture, where they also display embayments. While the Loivos porphyry only presents antirapakivi feldspars, the PA and VNFC veins show both antirapakivi and rapakivi. In the antirapakivi crystals, the potassium feldspar rims are incomplete, subhedral, and mostly altered to kaolinite (Figure 4e). In the rapakivi feldspars, the plagioclase rims are either complete or incomplete, mainly euhedral, and usually present myrmekite intergrowths (Figure 4f). K-feldspar in the VPA and VNFC porphyries is mainly orthoclase (± sanidine ± adularia) and occasionally microcline.

Plagioclase is exclusive to the phenocryst and microphenocryst population, exhibiting tabular habit and a predominant subhedral shape. Most crystals reveal polysynthetic twinning and some also show simple twinning. In all cases, oscillatory zoning is uncommon and the phenocrysts exhibit occasional fractures, which may be filled by groundmass minerals. Based on the Michel–Lévy method, plagioclase in all porphyries is, possibly, albite–oligoclase: An2–An12 (Loivos), An0–An8 (PA), and An6–An18 (VNFC).

Cordierite is more common in the PA vein. Cordierite crystals are exclusively phenocrysts or microphenocrysts. Their habit is typically tabular or rarely prismatic, while the shape is subhedral to euhedral. Regarding textures and microstructures, cordierite microphenocrysts reveal rare embayments. The latter and the homogeneous distribution of cordierite in thin sections attest to a magmatic origin for this mineral [Alasino et al. 2004].

The VPA and VNFC porphyries are richer in muscovite than biotite. The white mica occurs mostly at the groundmass level, in very fine grains, with an anhedral or subhedral shape and needle-like habit. However, scarce larger primary muscovite crystals (microphenocryst-like) are also present in the VPA veins. These are subhedral in shape, lamellar in habit, and may present cleavage bending or kinks (Figure 4g).

Biotite occurs in microphenocrysts of lamellar or tabular habit and subhedral shape, whose size is typically smaller when compared to the quartz, feldspar, and cordierite counterparts. The abundance of this mineral is the lowest in the PA porphyry. Fresh biotite reveals many pleochroic halos where prismatic crystals of zircon, monazite, and apatite are included. The dark mica is also frequently associated with late-stage chlorite (whose very fine and anhedral grains display radial texture) and opaque minerals. Microstructures, such as cleavage bending and kinks, were occasionally observed in larger lamellar crystals. In the aphyric facies of the PA and VNFC porphyries, biotite is very scarce and mostly altered to chlorite.

Apatite crystals show prismatic, rounded, or needle-like habits, as well as hexagonal–euhedral or anhedral shapes.

Opaque grains are typically very fine, anhedral or euhedral in shape, and prismatic or needle-like in habit. They are either dispersed throughout the groundmass or included in biotite and cordierite microphenocrysts. All veins have fractures cutting through the groundmass and phenocrysts, which are filled with Fe oxides and/or opaque minerals. Considering the magnetic susceptibility values registered on the field (Km = 22.03–49.55 μSI [Loivos]; ≈60–81 μSI [PA]; 62.32–74.25 μSI [VNFC]), these opaque crystals are mostly paramagnetic minerals such as ilmenite, which was verified in SEM-EDS. The analysis revealed a Fe–Ti oxide composition, with minor Nb and Ta contents. According to Stimac and Hickmott [1994], both niobium and tantalum are common, albeit minimal, impurities in ilmenite. Vestigial amounts of other oxides, namely columbite–tantalite [(Mn,Fe)(Ta,Nb)2O6] and cassiterite [SnO2], have only been detected in PA.

Zircon and monazite are exceptionally rare accessory minerals. Both are mainly included in biotite microphenocrysts, where they are surrounded by pleochroic halos.

Allanite is an extremely rare phase in the mineral assemblage of the PA porphyry. This mineral occurs in prismatic, euhedral crystals, which are closely associated with the biotite or potassium feldspar and occasionally reveal zoning.

Childrenite [FeAl(PO4)(OH)2 ⋅ H2O], probable scorzalite [FeAl2(PO4)2(OH)2], and gayite [NaMnFe5(PO4)4(OH)6 ⋅ 2H2O] are the least common minerals of the PA vein. These phosphates were identified during the SEM-EDS analysis. Childrenite is the most common, occurring in large phenocryst or microphenocryst-like grains of tabular habit and subhedral or anhedral shape. Childrenite is always associated with feldspar phenocrysts and microphenocrysts. On the other hand, scorzalite and gayite occur in smaller crystals (maximum 100 μm long) of anhedral habit. They are always included in the potassium feldspar phenocrysts. Further analyses are required to confirm the presence of these two minerals.

All porphyries were subjected to post-magmatic alterations as evidenced by the following petrographic features: (i) partial or complete kaolinization of K-feldspar, which sometimes masks the twinnings and perthites; (ii) sericitization and saussuritization of plagioclase; (iii) biotite muscovitization and chloritization; and (iv) cordierite pinitization (all cordierite is completely altered to pseudomorphs of chlorite and white mica (Figure 4h)). Secondary minerals, such as brookite, anatase, and the Fe oxides, resulted from the alteration of biotite and cordierite. The presence of brookite and anatase was confirmed throughout the SEM-EDS analysis after detecting a Ti-oxide composition and minor Nb impurities, which are typical of both brookite and anatase [Werner and Cook 2001, Barnard et al. 2019]. The respective grains show prismatic habit and anhedral or euhedral shape. On the other hand, the Fe oxides (hematite and goethite mostly) are always anhedral.

Major, minor, and trace element contents of the Vila Pouca de Aguiar and Vila Nova de Foz Côa porphyries

| Samples | 61-1 | 61-B | 61-1C | D1 | 61-2 | 61-2A | 61-6Ca | 61-6Cb | CC green | CC pink | VNFC1 | VNFC2A | VNFC2B* | VNFC3A | VNFC3B* | VNFC5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithology | Póvoa de Agrações porphyry | Loivos porphyry | Compact lithology | Vila Nova de Foz Côa porphyry | ||||||||||||

| SiO2 | 72.78 | 72.42 | 72.29 | 72.56 | 73.19 | 72.83 | 74.15 | 73.07 | 71.54 | 71.35 | 72.32 | 72.75 | 73.15 | 75.37 | 76.43 | 73.73 |

| TiO2 | 0.055 | 0.052 | 0.041 | 0.042 | 0.097 | 0.099 | 0.102 | 0.102 | 0.034 | 0.032 | 0.142 | 0.144 | 0.068 | 0.140 | 0.056 | 0.152 |

| Al2O3 | 15.77 | 14.98 | 15.06 | 15.83 | 15.01 | 14.47 | 14.35 | 14.04 | 16.21 | 15.72 | 14.26 | 14.47 | 13.95 | 14.17 | 13.53 | 14.60 |

| 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 0.70 | 1.07 | 1.39 | 0.91 | 1.36 | 1.11 | 1.53 | |

| MnO | 0.062 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.047 | 0.032 | 0.025 | 0.030 | 0.028 | 0.060 | 0.041 | 0.022 | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.039 | 0.062 | 0.034 |

| MgO | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| CaO | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.27 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.55 |

| Na2O | 4.02 | 3.77 | 4.64 | 3.80 | 3.27 | 3.13 | 3.24 | 3.18 | 3.73 | 3.98 | 2.53 | 2.68 | 1.68 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 2.94 |

| K2O | 3.92 | 3.84 | 3.79 | 3.84 | 4.49 | 4.68 | 4.67 | 4.72 | 3.89 | 3.80 | 4.73 | 4.80 | 5.01 | 6.37 | 4.10 | 4.64 |

| P2O5 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.28 | 0.76 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.27 |

| LOI | 1.38 | 1.56 | 1.13 | 1.79 | 1.39 | 1.43 | 1.35 | 1.35 | 1.88 | 1.58 | 3.18 | 2.65 | 2.98 | 2.28 | 2.46 | 1.47 |

| Total | 100.30 | 98.98 | 98.53 | 100.20 | 99.54 | 98.76 | 100.20 | 98.70 | 98.95 | 98.83 | 99.25 | 99.98 | 98.80 | 100.80 | 98.62 | 100.20 |

| Be | 49 | 42 | 20 | 21 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 57 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 14 | 8 |

| Ba | 55 | 58 | 47 | 39 | 82 | 109 | 95 | 91 | 31 | 20 | 185 | 190 | 61 | 191 | 25 | 193 |

| Sr | 94 | 68 | 48 | 68 | 23 | 25 | 29 | 28 | 16 | 39 | 42 | 43 | 18 | 36 | 5 | 49 |

| Y | 10 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 6 | 7 | 15 | 14 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 15 |

| Zr | 46 | 41 | 31 | 38 | 42 | 39 | 48 | 40 | 32 | 30 | 73 | 75 | 30 | 70 | 22 | 80 |

| Rb | 1240 | 1110 | 856 | 1370 | 349 | 331 | 339 | 345 | 1460 | 1290 | 362 | 362 | 509 | 626 | 508 | 314 |

| Nb | 45 | 35 | 35 | 53 | 13 | 10 | 18 | 11 | 47 | 39 | 14 | 13 | 19 | 14 | 14 | 13 |

| Sn | 182 | 151 | 209 | 214 | 35 | 23 | 29 | 24 | 344 | 240 | 23 | 24 | 61 | 69 | 69 | 20 |

| Cs | 238.0 | 271.0 | 84.1 | 118.0 | 34.0 | 30.8 | 29.2 | 29.9 | 187.0 | 99.1 | 23.8 | 30.7 | 32.7 | 36.6 | 29.7 | 25.0 |

| La | 6.0 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 3.3 | 15.3 | 1.3 | 13.6 |

| Ce | 13.9 | 13.1 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 16.5 | 17.1 | 16.5 | 17.1 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 30.9 | 33.2 | 7.2 | 32.9 | 3.5 | 30.0 |

| Pr | 1.62 | 1.67 | 1.29 | 1.22 | 2.23 | 2.19 | 1.92 | 2.17 | 1.21 | 0.99 | 3.58 | 3.79 | 0.87 | 3.81 | 0.49 | 3.57 |

| Nd | 6.3 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 13.4 | 13.6 | 3.2 | 13.4 | 2.2 | 13.3 |

| Sm | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 3.1 |

| Eu | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| Gd | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 2.9 |

| Tb | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Dy | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 2.9 |

| Ho | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Er | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Tm | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.14 | <0.05 | 0.19 |

| Yb | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Lu | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| Hf | 3.0 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 2.5 |

| Ta | 28.0 | 29.1 | 35.5 | 34.8 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 44.5 | 43.5 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 9.5 | 4.3 | 6.8 | 3.7 |

| W | 13 | 16 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 7 |

| Pb | 13 | 10 | 15 | 8 | 25 | 13 | 20 | 19 | <5 | 13 | 31 | 30 | 30 | 125 | 13 | 20 |

| Th | 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 2.4 | 9.3 | 1.8 | 8.9 |

| U | 21.9 | 17.8 | 19.3 | 21.0 | 14.6 | 11.4 | 16.2 | 16.2 | 28.5 | 21.8 | 7.4 | 12.6 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 8.5 | 11.9 |

| Li | 850 | 1030 | 80 | 540 | 120 | 70 | 60 | 60 | 190 | 300 | 120 | 150 | 140 | 110 | 80 | 180 |

| F | 2600 | 3200 | 300 | 1700 | 4500 | 500 | 300 | 300 | 800 | 1200 | 600 | 600 | 700 | 600 | 300 | 400 |

| 𝛴REE | 34.94 | 33.08 | 24.84 | 26.68 | 44.80 | 45.27 | 42.64 | 44.61 | 23.48 | 20.33 | 75.84 | 78.68 | 18.66 | 75.32 | 10.31 | 73.62 |

| (La/Yb)N | 5.06 | 5.59 | 4.83 | 4.43 | 5.26 | 5.69 | 5.69 | 5.92 | 4.43 | 3.93 | 6.89 | 7.42 | 5.56 | 11.46 | 2.92 | 7.05 |

| (La/Sm)N | 2.36 | 2.28 | 2.08 | 2.41 | 2.23 | 2.08 | 2.39 | 2.26 | 2.63 | 1.83 | 3.10 | 2.73 | 2.31 | 3.56 | 1.36 | 2.76 |

| (Gd/Yb)N | 1.51 | 1.73 | 1.48 | 1.50 | 1.86 | 2.06 | 1.79 | 1.88 | 1.27 | 1.61 | 1.84 | 1.92 | 1.82 | 1.97 | 1.61 | 1.80 |

| (Eu/Eu*)N | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.28 |

| TE1,3 | 1.11 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.22 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 1.16 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.17 | n.d. | 1.11 |

Major and minor elements are expressed in weight percentage (wt%), while the trace elements are in parts per million (ppm). Legend: n.d.—not determined. Samples VNFC2B and 3B represent the aphyric facies of the VNFC porphyry. TE1,3 is the degree of the tetrad effect [Irber 1999].

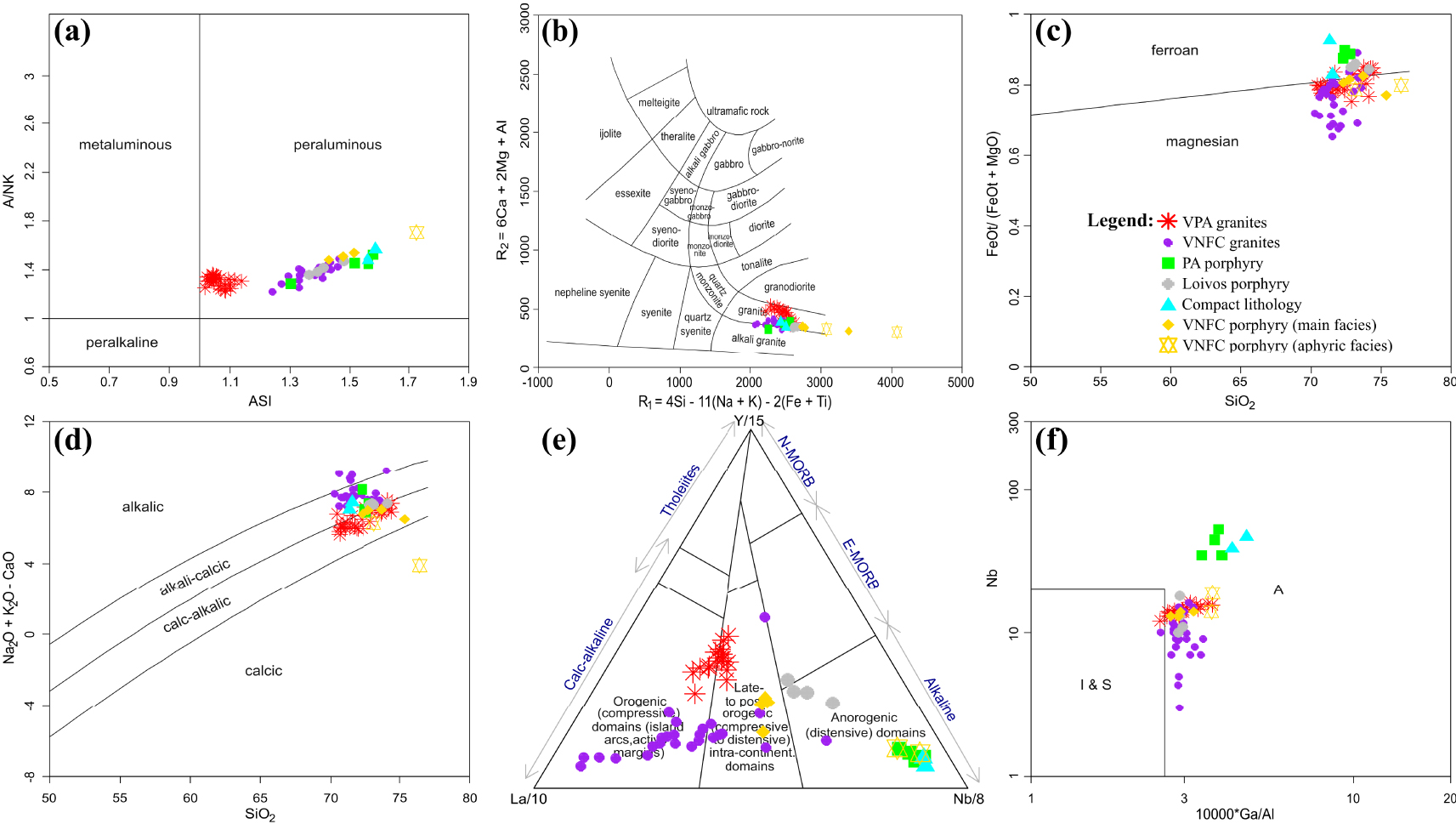

Projection of the VPA and VNFC porphyries in the following diagrams: (a) ASI vs. A/NK [Frost et al. 2001]; (b) R1 vs. R2 [De La Roche et al. 1980]; (c) SiO2 vs. FeOt/(FeOt + MgO) [Frost et al. 2001]; (d) SiO2 vs. Na˙2O + K2O—CaO [Frost et al. 2001]; (e) La/10-Y/15-Nb/8 [Cabanis and Lecolle 1989]; (f) 10,000 × Ga/Al vs. Nb [Whalen et al. 1987].

4.2. Whole-rock geochemistry

The bulk-rock compositions of the VPA and VNFC porphyries are presented in Table 1. As mentioned above, the compact lithology that appears next to the PA vein was also analyzed. For comparative purposes, the geochemical data concerning the respective regional granites [Martins et al. 2009, Ferreira et al. 2020] is illustrated but not described in this paper. Based on the results, there is no evidence suggesting the existence of any sort of genetic relationship between the porphyries and granites.

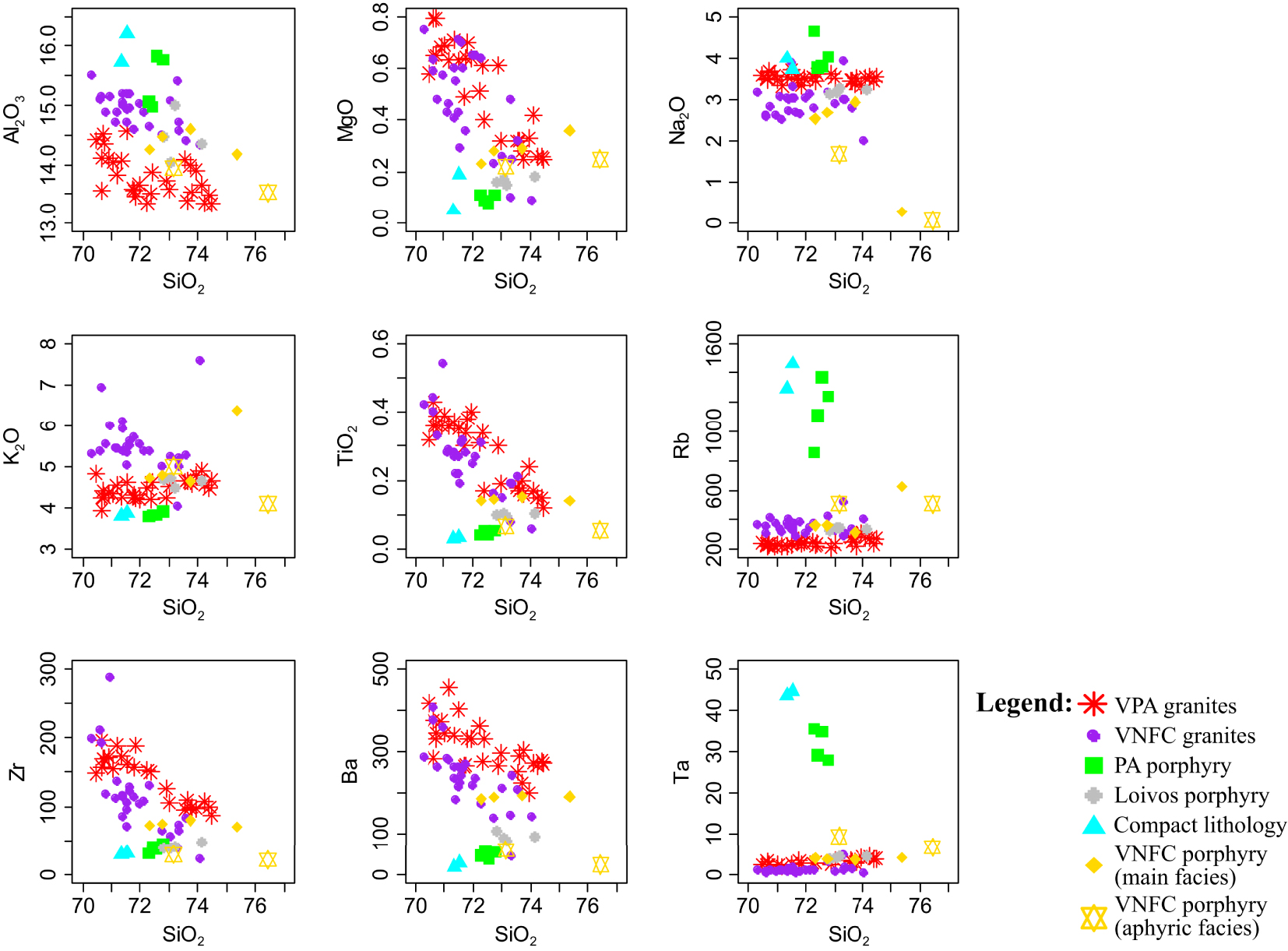

Harker diagrams for major, minor, and trace elements of the VPA and VNFC porphyries.

The granitic/rhyolitic porphyries of the VPA and VNFC regions are high-K calc-alkaline rocks and strongly peraluminous, as indicated by their high ASI values (VPA: 1.27–1.45; VNFC: 1.39–1.92) (Figure 5a). In VPA, the compact lithology presents a slightly higher alumina saturation (ASI = 1.42–1.55). On the other hand, the aphyric facies of the VNFC vein displays abnormally high ASI values (ASI = 1.64–2.87), causing the respective samples to be projected outside the normal range of the De La Roche et al. [1980] diagram (Figure 5b). The low Na2O contents and high ASI suggest that the aphyric rock was significantly affected by post-magmatic alterations. As such, the respective samples cannot be used to gain information about primary magmatic features. For all porphyries, the normative compositions are identical to those of granites (sensu stricto) or alkali granites. However, while the VPA veins are ferroan and alkali-calcic, the VNFC specimen is magnesian and calc-alkalic to alkali-calcic (Figures 5c and d). The whole-rock geochemical results suggest that the VPA porphyries are associated with post-orogenic or anorogenic settings, whilst the geochemical signature of the VNFC vein is typical of syncollisional or late to post-orogenic environments (Figure 5e). Also, these subvolcanics lithologies display features resembling those of “A-type” granites [Whalen et al. 1987, Bonin 2007] (Figure 5f).

When comparing the VPA veins, the Loivos porphyry is richer in SiO2,

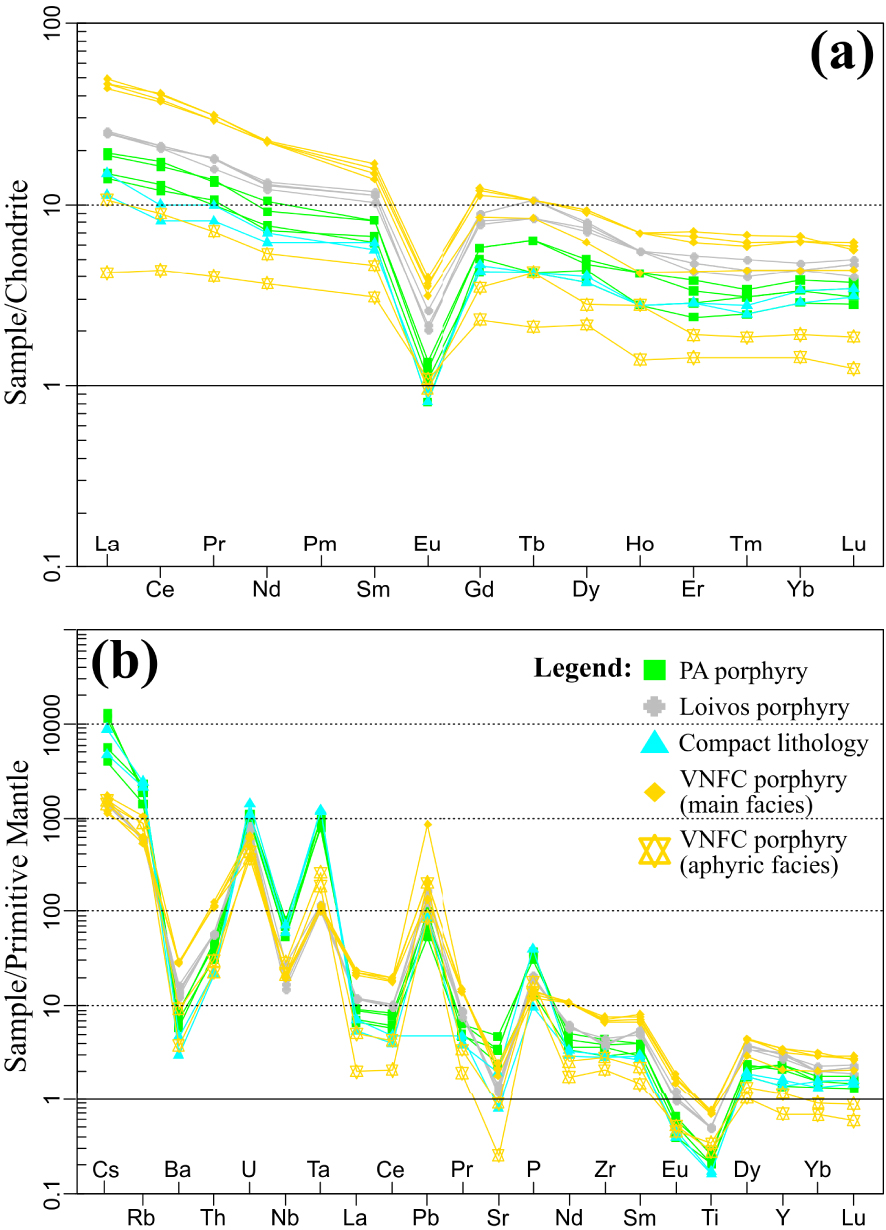

The REE spectra of the VPA and VNFC porphyries are illustrated in Figure 7a. Considering only the main facies of the veins, VNFC is the richest in REE, while PA is the poorest. The samples representing the aphyric facies of the VNFC specimen are strongly depleted, as is the compact lithology spatially associated with the PA porphyry. All REE spectra present a weak general fractionation, an LREE fractionation slightly more significant than the HREE fractionation, and negative, well-accentuated Eu anomalies. Overall, the VPA specimens are more homogeneous than the VNFC samples concerning the general REE fractionation (the difference is mainly due to the LREE). The Eu anomalies are more evident on the VPA profiles, especially on the ones illustrating the compact lithology. In the aphyric VNFC vein, the Eu anomalies are also clear.

Sm and Nd isotopic composition of the Vila Pouca de Aguiar and Vila Nova de Foz Côa porphyries

| Samples | Nd (ppm) | Sm (ppm) | 147Sm∕144Nd | 143Nd∕144Nd ± 2𝜎 | 𝜀Nd290 Ma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61-B | 6.30 | 1.59 | 0.1530 | 0.512362 ± 0.000007 | −3.76 |

| 61-1C | 4.47 | 1.18 | 0.1595 | 0.512359 ± 0.000007 | −4.07 |

| D1 | 4.53 | 1.26 | 0.1684 | 0.512361 ± 0.000005 | −4.36 |

| 61-2 | 8.01 | 2.17 | 0.1637 | 0.512361 ± 0.000004 | −4.19 |

| 61-2A | 8.02 | 2.26 | 0.1707 | 0.512380 ± 0.000004 | −4.07 |

| 61-6C | 7.85 | 2.07 | 0.1595 | 0.512359 ± 0.000006 | −4.07 |

| VNFC1 | 13.7 | 3.07 | 0.1354 | 0.512296 ± 0.000006 | −4.40 |

| VNFC3A | 12.3 | 2.48 | 0.1216 | 0.512277 ± 0.000006 | −4.26 |

| VNFC5 | 14.6 | 3.24 | 0.1342 | 0.512305 ± 0.000006 | −4.18 |

(a) REE diagrams for the VPA and VNFC porphyries. Chondrite normalization values after Boynton [1984]; (b) Multi-element spidergrams for the VPA and VNFC porphyries. Primitive mantle normalization values after McDonough and Sun [1995].

Multi-element spidergrams of the VPA and VNFC porphyries are presented in Figure 7b. The patterns for both VPA veins and the compact facies exhibit identical anomalies, which are always more pronounced in the PA specimen and compact rock profiles. All spidergrams, including those representing the VNFC porphyry, present clear positive anomalies in HFSE such as U and Ta, as well as in Cs, P, and Pb, and evident negative anomalies in LILE like Ba and Sr. Titanium, niobium, and LREE anomalies are also negative. Regarding the VNFC vein, both the positive and negative anomalies are more pronounced in the profiles of the aphyric facies. As the REE spectra, the normalized multi-element spidergrams of the VPA subvolcanic lithologies also display parallel patterns.

4.3. Sm–Nd isotope geochemistry

Three samples of each porphyry were selected to study the respective Sm–Nd isotope systems. The results are presented in Table 2. To calculate the 𝜀Ndi parameter, a crystallization age of 290 Ma, which is the age of the youngest post-D3 Variscan granites in Iberia, has been assumed. Overall, the VPA and VNFC veins exhibit similar isotopic compositions, with 𝜀Nd290 Ma = −3.76 to −4.40. The Loivos and VNFC porphyries are relatively homogeneous, while the PA vein displays a wider range of initial 𝜀Nd values. On average, the VPA specimens are more radiogenic in Nd than the VNFC porphyry.

5. Discussion

5.1. Petrogenesis and relationship with the granites

Several criteria suggest that the two porphyries of the VPA region are genetically related to each other. Both veins are N–S trending, the distance between them is regionally insignificant, and their mineral and bulk-rock geochemical compositions are very similar. As mentioned before, the third phase of the Variscan orogeny (D3) was responsible for the development of conjugated, NNE–SSW and NNW–SSE trending, brittle fracture systems. The emplacement of the VPA porphyries was most likely controlled by similar structures, which were generated during the late stages of phase D3 and superimposed by the post-tectonic D4 brittle phase [Dias et al. 2013]. However, since the kinematic evolution of many of these fractures is polyphasic and associated with both late-Variscan and Alpine events [Mateus and Noronha 2010], without geochronological results there is no definitive confirmation that the generation and emplacement of the VPA porphyries were related to the final contributions of the Variscan orogeny or the onset of the Alpine tectonics in northern Iberia. The presence of scarce magmatic to submagmatic microstructures such as kinks and weak undulatory extinction [Bouchez et al. 1992] favors the former hypothesis because there is no record of folding or ductile shearing on northern Portugal caused by the Alpine cycle [Jabaloy Sánchezet al. 2019]. On the other hand, the VNFC porphyry was emplaced along a WSW–ENE ductile shear zone. According to Silva and Ribeiro [1991], this structure also resulted from the onset of phase D3 on the portuguese CIZ. However, given the general orientation, the ductile shear was developed before the fractures where the VPA porphyries have emplaced [Dias et al. 2013]. As such, the regional structures and vein directions suggest that the emplacement of the VNFC porphyry took place before the emplacement of the VPA veins.

The main geochemical arguments in favor of a genetic relationship between the Loivos and PA porphyries are the parallel REE spectra and closeness of the 𝜀Nd290 Ma values. The small differences between the two VPA veins could be related to variations concerning the partial melting of the protolith and/or to the separate evolution of corresponding individual magma batches. Since the REE spidergrams of the compact lithology spatially associated with the PA porphyry are also parallel, this lithotype is probably a different facies of the eastern vein without phenocrysts, thus explaining the great similarities respecting mineralogy, texture, and geochemistry. The occurrence of the aphyric PA facies next to the GTMZ quartzphyllites and of a microgranite in the contact between the VPA granite and Loivos porphyry suggests that these lithologies represent a sharp thermal transition or chilled margins between the veins and respective host rocks. The same can be noted about the VNFC porphyry, whose aphyric facies probably constitutes a chilled margin at the contact with the regional host rocks (i.e., mainly syn-D3 granites). In the PA and VNFC cases, the higher thermal contrast between the porphyries and respective host rocks created microcrystalline, subvolcanic to volcanic textures. On the other hand, in Loivos, since the vein completely intruded into a post-D3 granite (which was warmer at the time of emplacement), the resulting transition is more phaneritic.

The highly evolved nature of the porphyries suggests that the melts from which they crystallized were subjected to crystal fractionation. The strong negative Eu anomalies possibly point to plagioclase fractionation in the source, without discarding possible inheritance from the protolith, while the (La/Sm)N ratios and low Zr + Hf + Y + Th contents are related to the crystal fractionation of apatite, zircon, allanite, and monazite [Zhu and O’Nions 1999]. As mentioned above, the REE spectra of the aphyric facies are parallel to the spectra of the porphyritic ones. Petrographically, the lack of phenocrysts and the absence of most accessory minerals in the aphyric varieties are directly related to the compositional differences between the two types of facies. Overall, the whole-rock geochemical data indicate that the PA porphyry is more fractionated than the Loivos vein. The previous statement is evidenced by multiple geochemical observations namely the following: (i) the higher

Considering the geochemical and isotope data of the regional Variscan granites [𝜀Ndi [VPA granite] = −2.47 to −2.54; Martins et al. 2009; 𝜀Ndi [VNFC granites] = −6.03 to − 8.89; Ferreira et al. 2020], our results suggest that the sources from which the porphyries derived are different compared to those from which the granites were generated. The average bulk-rock compositions and geochemical classifications of the least altered samples point out the higher evolutionary degree of the subvolcanic rocks. The enrichment in rare incompatible metal elements is most likely associated with fractionation of a feldspar and biotite-dominated assemblage, generating high contents in LILE such as Li, Be, Rb, and Cs [Canosa et al. 2012, Simonset al. 2017]. As the magmatic system evolved, the residual melts from which the porphyries crystallized became enriched in the latter elements, as well as in Sn, Nb, Ta, and W, due to their highly incompatible behavior. In the veins, the LILE were probably partitioned into muscovite and K-feldspar through the substitution of K [Canosa et al. 2012]. On the other hand, the high P2O5 and F contents promoted the retention of HFSE (Sn, Nb, Ta, W) in the porphyry melts [Simonset al. 2017], resulting in their partition into Fe and Ti oxides (ilmenite and, to a lesser extent, biotite), Nb and Ta oxides (columbite–tantalite), and Sn oxides (cassiterite), as verified with the SEM-EDS analysis. Since tungsten is preferentially incorporated into muscovite in granitic melts of lower temperature [Simonset al. 2017], the veins also became enriched over the granites.

As previously mentioned, the studied porphyries resemble “A-type” granitoids which is mostly evidenced by their high HFSE and F contents, elevated Ga/Al ratio, post-orogenic signatures, and presence of rare phosphates [Whalen et al. 1987, Bonin 2007]. Several theories have been proposed to explain the petrogenesis of this controversial group of igneous rocks [e.g. Bonin 2007, Magna et al. 2010, Sarjoughian et al. 2015, and references therein]. The main petrogenetic models are summarized in the following list: (i) remelting of a granulitic residue that was left in the lower crust after a previous extraction of “I-type” granite melts; (ii) anatexis of quartzofeldspathic (meta)igneous crustal rocks; (iii) mixing of magmas derived from crustal and OIB sources; (iv) significant crystal fractionation of mantle-derived mafic melts; (v) generation from a depleted upper mantle reservoir altered by subduction-related fluids; and (vi) anatexis of a lower crustal source, previously metasomatized by mantle-derived fluids. Considering the peraluminous nature of the veins, the low Zr and REE contents, the lack of alkali-rich amphiboles and/or sodic pyroxenes, and the absence of significant volumes of alkaline rocks near the porphyry outcrops, the last three models are refuted [Martin 2006, Bonin 2007]. On the other hand, the granulitic residue remelting scenario is excluded due to the enriched nature of the VPA pluton [Martins et al. 2009]. If the veins had been generated from such a residue, their contents in rare incompatible metal elements would be lower than those of the granites. In the multi-element spidergrams, the anomalies revealed by the VPA and VNFC porphyries imply that the magmas from which the veins crystallized must have been derived from evolved crustal sources [Nédélec and Bouchez 2015]. The evolved nature of the porphyry sources is also evidenced by the weakly fractionated REE spectra [Wu et al. 2017]. However, considering the Nd isotope signatures, magma mixing might have occurred. As such, the likeliest petrogenetic model is the anatexis of quartzofeldspathic crustal rocks under reducing conditions (since the magnetic mineralogy is dominated by ilmenite and biotite), with probable influence of compositionally different melts, followed by significant crystal fractionation.

The REE spectra of the aphyric facies are slightly arcuate in the profiles of both LREE and HREE (especially in the case of VNFC), reflecting the REE tetrad effect [Peppard et al. 1969, Irber 1999] generated from hydrothermal influences (under magmatic to hydrothermal subsolidus conditions as proposed by Ballouard et al. [2016a]). The stronger rubefaction in the PA vein highlights the higher degree of hydrothermalism. Geochemically, the low K/Rb and Nb/Ta ratios also point out the severe hydrothermal alterations (Loivos: 128.65 < K∕Rb < 141.39; 2.68 < Nb∕Ta < 4.09; PA: 26.64 < K∕Rb < 44.28; 0.90 < Nb∕Ta < 1.61; VNFC: 66.97 < K∕Rb < 122.62; 2.00 < Nb∕Ta < 3.51) and suggest that crystal fractionation of biotite and ilmenite have played an important role in the geochemical evolution of the porphyries [Ballouard et al. 2016a,b, 2020]. Since these alterations seem to have been caused by F-rich fluids, some apatite and the rare phosphates of the VPA veins possibly resulted from the transformation of P-rich alkali feldspars [Bea et al. 1992, Broska et al. 2004]. On the other hand, post-magmatic processes have affected the geochemistry of the aphyric samples and are presumably responsible for the depletion in Na˙2O [Förster et al. 2007]. Due to these phenomena, the K2O and Rb contents of the phenocryst-free samples may also be lower than in the unaltered ones, thus generating a less alkalic nature.

5.2. Texture development

The generation of porphyritic aphanitic textures in volcanic and subvolcanic rocks of rhyolitic/granitic composition is mainly explained by magmatic histories involving two separate melt cooling episodes [Best and Christiansen 2001]. The first episode is associated with a slow cooling rate and small undercooling, resulting in large phenocrysts of variable size. Phenocryst growth typically occurs deep below the surface in magmatic reservoirs. On the other hand, the second cooling episode takes place at shallow depths after a rapid heat loss. The fast cooling, combined with a large nucleation rate and low growth rate, explains the multiple finer crystals that compose the aphanitic groundmass. However, there are other theories about the development of this type of igneous texture, such as a single, long, continuous cooling event where the first mineral to precipitate from the liquidus crystallizes alone for a long period of time, causing strong supersaturations in the melt [Vernon 2004]. Another widely recognized and accepted theory involves two stages of fluid saturation. The initial phenocryst nucleation and growth are promoted by a first stage of volatile supersaturation, while the second stage takes place after isothermal decompression and devolatilization of the melt. This hypothesis is more suited to explain the bimodal granularity of porphyry masses [Ferreira and Ribeiro 2018]. Considering the textural variety displayed by the VPA and VNFC porphyries, both fast cooling and volatile loss have probably played a crucial role.

All studied porphyries exhibit three different grain size populations: (i) the earlier phenocrysts and microphenocrysts; (ii) the coarser groundmass grains; and (iii) the finer groundmass crystals. Assuming that the phenocrysts and microphenocrysts were generated in conditions of fluid supersaturation, the presence of embayments in quartz [formed from resorption or dendritic growth; Barbey et al. 2019, Barbee et al. 2020] and the micrographic intergrowths (granophyric texture) constitute an indirect evidence of varying cooling rates and undercooling magnitude [Štemprok et al. 2008]. Since the porphyries occur as veins, a rapid (and nearly isothermal) magma ascent is presumed. Isothermal decompression can lead to the partial resorption of quartz and feldspar, until fluid saturation conditions are reached, resulting in a melt fraction increase and the development of embayments. Under fluid-saturated conditions, quartz may undergo renewed growth, and novel plagioclase and K-feldspar crystallization is possible [Štemprok et al. 2008]. If the novel feldspar crystallization is epitactic, rapakivi and antirapakivi feldspars can be formed [Nekvasil 1991, Corretgé and Suárez 1994]. As the decompression progresses, the melt is increasingly cooled due to the rapid heat transfer onto the host rocks, triggering a significant devolatilization and crystallization of the residual melt in very fine groundmass grains. The groundmass crystals (or microliths) formed through this process are commonly arranged around the phenocrysts [Ferreira and Ribeiro 2018]. At shallow emplacement levels, cooling rates for the porphyry melts are expected to be high. However, in the case of the Loivos porphyry, since the vein is completely hosted in a post-D3 granite, which was warmer at the time of emplacement, the cooling rate may have been lower. As such, it is possible to presume that the coarser groundmass grains resulted from subsolidus annealing which coarsened and partially eliminated the finer groundmass [Higgins 1999, 2000, Štemprok et al. 2008]. On the other hand, the PA porphyry was emplaced closer to the edge of the VPA pluton, next to metasedimentary rocks, and the VNFC vein is hosted in colder syn-D3 granites and metasediments. In these cases, at the time of porphyry emplacement, the thermal contrast was more significant, and the groundmass coarsening was presumably hindered.

5.3. Antirapakivi and rapakivi feldspars

Various theories have been proposed to explain the generation of rapakivi and antirapakivi feldspars in plutonic, subvolcanic, and volcanic settings. The two most accepted hypotheses are based on isothermal decompression of granitic melts [Nekvasil 1991, Corretgé and Suárez 1994] and mixing or mingling of two compositionally distinct magmas [Abbott 1978, Hibbard 1981, Stimac and Wark 1992, Wark and Stimac 1992, Andersson and Eklund 1994, Müller and Seltmann 2002, Seltmann and Müller 2002, Müller et al. 2005, 2008, O’Brien et al. 2019]. Some authors believe that both phenomena are crucial in the development of rapakivi textures, although attributing greater importance to the magma mixing [Rämö and Haapala 1995, Vernon 2016]. Other (and less recognized) models such as synneusis [Stull 1979] and subsolidus exsolution [Dempster et al. 1994] have been refuted.

The discrimination of the contributions of magma mixing and isothermal decompression on the development of mantled feldspars in individual intrusions is very difficult [Vernon 2016]. As mentioned above, the groundmass crystals arranged around the phenocrysts, the embayments on quartz and K-feldspar phenocrysts, and the granophyric texture collectively suggest that the porphyry melts were subjected to devolatilization and isothermal decompression. Geochemically, the high variability of all porphyries regarding their fluorine contents constitutes another argument in favor of variable undercooling rates and volatile loss [Boyle 1976, Bailey 1977]. However, the influence of magma mixing should not be discarded, especially in high-level intrusions such as granite porphyries. Concerning the VPA and VNFC veins, the only feature that is undeniably related to mixing of two compositionally distinct magmas is the coexistence of mantled and non-mantled feldspar phenocrysts [Vernon 2016].

Rämö and Haapala [1995] stated that most granites exhibiting rapakivi texture are associated with mafic rocks such as gabbros, norites, anorthosites, dolerites, and basalts, which represent the mafic member of the bimodal magmatism typically associated with rapakivi suites. While in VPA there are no such lithologies in the vicinities of the porphyries, in the VNFC region there are multiple small microgabbro veins close to the regional porphyry. These microgabbros are, like the porphyry, emplaced along late to post-D3 structures. Geochemically, the three granitic veins present some characteristics typical of rapakivi granites, namely the high SiO2, F, K2O, Rb, Th, and U, and low CaO, MgO, and Sr contents, and the post-orogenic signature. In the case of magma mixing, the development of the rapakivi/antirapakivi textures should have occurred in the deeper magma reservoir where the phenocrysts were formed. On the other hand, if the mantled feldspars were generated during decompression, they formed during the ascent of the magmas along the veins. Considering the results presented in this work, both magma mixing and isothermal decompression may be regarded as the phenomena responsible for the petrographic, textural, and geochemical evolution of the VPA and VNFC porphyries.

6. Conclusions

The Vila Pouca de Aguiar and Vila Nova de Foz Côa porphyries are three of the most regionally significant subvolcanic veins of northern Portugal and portuguese Central Iberian Zone. The following interpretations were reached based on field, petrographic, textural, SEM-EDS, whole-rock geochemical, and Sm–Nd isotope studies:

(1) Considering their geometry, spatial proximity, mineral assemblages, and bulk-rock chemical compositions, the Loivos and Póvoa de Agrações porphyries of the VPA region are possibly genetically related to each other. Despite its less evolved nature, the VNFC vein presumably derived from a similar source;

(2) All of the studied porphyries were emplaced along structures generated during the final phase of the Variscan orogeny and reactivated with the Alpine cycle. The presence of magmatic to submagmatic microstructures suggests that porphyry emplacement occurred toward the end of the Variscan orogeny. Based on the general vein orientation, the VPA subvolcanics are probably (slightly) younger than the VNFC counterpart;

(3) Both the PA and VNFC porphyries exhibit two facies, the main porphyritic one, and the other, practically phenocryst-free, and aphyric. The aphyric facies and the microgranite that is spatially associated with the Loivos vein are chilled margins or transitional lithologies between the main porphyritic facies and the respective regional host rocks. The textural differences between these lithologies are related to the magnitude of the thermal contrasts at the time of emplacement;

(4) The likeliest petrogenetic model is the anatexis of quartzofeldspathic crustal rocks, under reducing conditions, seemingly influenced by compositionally different melts resulting in magma mixing, followed by significant crystal fractionation. Based on the geochemical data, the sources from which the regional granites were generated are not the same;

(5) The three veins were significantly affected by subsolidus hydrothermal fluids, as indicated by several petrographic and geochemical evidence, namely rubefaction, the presence of rare phosphates, low K/Rb and Nb/Ta ratios, and the REE tetrad effect;

(6) All porphyries are enriched in rare metal incompatible elements. SEM-EDS analyses showed that some of these metals (Nb, Ta, Sn) are concentrated in various oxides (ilmenite, brookite, anatase, columbite–tantalite, cassiterite). The remaining elements (Li, Be, Rb, Cs, W) are probably incorporated in muscovite and K-feldspar. Despite the small distance separating the VPA veins, Póvoa de Agrações is significantly richer in all of these elements, which is possibly due to both crystal fractionation and hydrothermalism;

(7) The textural evolution of the VPA and VNFC porphyries was probably conditioned by fast cooling, volatile loss, and subsolidus annealing. Presumably, the latter process preferentially affected the Loivos vein;

(8) Based on the results of this research, both isothermal decompression and magma mixing are likely to have played an important role in the petrogenesis of the studied porphyries.

Further investigation, such as geochronology and more isotope studies, is required to fully understand the differences between these porphyries and to improve the current state of knowledge regarding the felsic vein magmatism in northern Portugal.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), through the project reference UIDB/04683/2020—ICT (Institute of Earth Sciences). The corresponding author is also financially supported by FCT through an individual PhD grant (reference SFRH/BD/138818/2018). The authors thank Professor Fernando Noronha (ICT, Porto Pole) for his help during the field studies, Daniela Silva (CEMUP) for her assistance throughout the SEM-EDS sessions, and Dr. Javier Rodríguez (SGIKER, University of the Basque Country) for the isotopic analyses. We also acknowledge Professor Pierre Barbey, an anonymous reviewer, and editor Bruno Scaillet whose comments helped to greatly improve the quality of the original manuscript.

| Samples | Location | Lithology | Latitude | Longitude |

| 61-1 | VPA | PA porphyry | N 41° 36′ 28′′ | W 7° 29′ 24′′ |

| 61-1C | VPA | PA porphyry | N 41° 36′ 28′′ | W 7° 29′ 24′′ |

| 61-B | VPA | PA porphyry | N 41° 37′ 32′′ | W 7° 29′ 56′′ |

| D1 | VPA | PA porphyry | N 41° 37′ 58′′ | W 7° 29′ 21′′ |

| 61-2 | VPA | Loivos porphyry | N 41° 36′ 31′′ | W 7° 30′ 24′′ |

| 61-2A | VPA | Loivos porphyry | N 41° 37′ 27′′ | W 7° 30′ 16′′ |

| 61-6Ca | VPA | Loivos porphyry | N 41° 35′ 52′′ | W 7° 32′ 22′′ |

| 61-6Cb | VPA | Loivos porphyry | N 41° 35′ 52′′ | W 7° 32′ 22′′ |

| Micro | VPA | Microgranite | N 41° 37′ 45′′ | W 7° 30′ 18′′ |

| CC green | VPA | Compact lithology | N 41° 37′ 58′′ | W 7° 29′ 21′′ |

| CC pink | VPA | Compact lithology | N 41° 36′ 28′′ | W 7° 29′ 24′′ |

| VNFC1 | VNFC | VNFC porphyry (main facies) | N 40° 59′ 35′′ | W 7° 9′ 58′′ |

| VNFC2A | VNFC | VNFC porphyry (main facies) | N 40° 59′ 38′′ | W 7° 9′ 57′′ |

| VNFC2B | VNFC | VNFC porphyry (aphyric facies) | N 40° 59′ 38′′ | W 7° 9′ 57′′ |

| VNFC3A | VNFC | VNFC porphyry (main facies) | N 40° 59′ 37.7′′ | W 7° 9′ 48.5′′ |

| VNFC3B | VNFC | VNFC porphyry (aphyric facies) | N 40° 59′ 37.7′′ | W 7° 9′ 48.5′′ |

| VNFC5 | VNFC | VNFC porphyry (main facies) | N 40° 59′ 17.3′′ | W 7° 8′ 13.4′′ |

Polished thin sections of the VPA porphyries were analyzed through scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). SEM-EDS usage was deemed necessary due to the extremely fine granularity that these subvolcanic rocks exhibit. This analytical methodology was also crucial in the identification of certain unusual minerals. Selected samples were examined at the IMICROS laboratory, CEMUP (Imaging, Microstructure, and Microanalysis Unit of the Materials Center, Porto University), using a high-resolution scanning electron microscope with X-ray microanalysis: model JEOL JSM 6301F/Oxford INCA Energy 350. All analyzed samples were previously coated by vapor deposition with a fine carbon film, using a JEOL JEE-4X Vacuum Evaporator equipment. The conditions in which the X-ray spectra were obtained are the following: accelerating voltage—15 kV; work distance (WD)—15 mm. The detection limit for all elements (from boron to uranium) is 0.1%.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0