1. Introduction

Tethyan mountain belts such as the Alps and the Hellenides served as key-sites for defining new tectonic concepts such as the notion of nappes derived from isopic zones, defined as domains with coherent stratigraphy and paleogeography. They were reinterpreted in the framework of “new global tectonics” in the early 70s. Presently, they are now the center of attention of a large community working on the interaction between subduction dynamics and crustal deformation. The evolution of Mediterranean back-arc basins, such as Alboran, Tyrrhenian, and Aegean seas is nowadays explained by new concepts of subduction dynamics that have flourished since the development of seismic tomography, seismic anisotropy, analog and numerical modelling, but also the improvement of field tectonic and metamorphic studies. The Aegean Sea is emblematic of this evolution and several schools have developed evolutionary models based on new concepts and observations.

Strangely, the Hellenic mountain belt has not been given the same attention in the recent period. On the other hand, the early part of the tectonic history of the Aegean region, before the change in subduction dynamics leading to back-arc extension some 30–35 Ma ago, is rather poorly documented despite the emblematic character of this large alpine-type Hellenic belt, including the Aegean back-arc.

Jean Aubouin was a prominent figure among those who developed the early concepts on the Hellenides, since his thesis [Aubouin 1959], followed by many collaborative works [references in Jacobshagen 1986 and Ferriere and Faure 2024]. Jean Aubouin’s school unraveled a large part of the External Hellenides while Jan Brunn and his students were mainly working in the Internal Zones. Both schools worked in detail on the Pelagonian domain located in the most external part of the Internal Zones, particularly well-known for the occurrence of huge volumes of ophiolitic material. Consequently, important ophiolitic complexes from the Eastern Hellenides have been the subject of multiple studies. One of the first ophiolite models corresponding to a massive submarine magmatic outflow (“Ophiolitic balloon model”) has been proposed by the studies carried out in northern Greece [Brunn 1956; Aubouin 1959].

The development of the concept of obduction developed in the early 70s [Coleman 1971; Dewey and Bird 1971] reinforced the interest in the study of Hellenic ophiolites that served as new models such as the Vourinos, North-Pindos and Othris ophiolitic units [e.g. Smith et al. 1975; Beccaluva et al. 1984].

A large part of the current knowledge was established during this initial period (60s–70s), when field geologists mapped the Greek territory as well as the Dinarides in former Yugoslavia. Yet, although it may be less visible than the many projects developed in the back-arc region, the geological knowledge has since considerably improved in the continental part of the Hellenides but the consequences on the recent evolution have not been fully explored. One symptomatic observation of a certain lack of attention drawn to the Hellenides is the absence of crustal-scale cross-sections similar to those proposed in the Alps or the Betic-Rif. Nevertheless, one can mention recent work providing detailed kinematic reconstructions [van Hinsbergen et al. 2020] or correlations between tectonic units [Schmid et al. 2020] published on the evolution of the Alps and the Balkans/Hellenides. A different approach was used by Menant et al. [2016a, b] who reconstructed the magmatic and metallogenic evolution of the Hellenides and Taurides from the Late Cretaceous to the Present and discussed the implications in terms of subduction dynamics.

In this contribution we summarise the most recent findings, mainly stemming from the Internal Hellenides, and show their implications for the geodynamic evolution of this wide region. Moreover, we show how the Hellenides can be used as a general model for Mediterranean mountain belts.

2. Geological setting

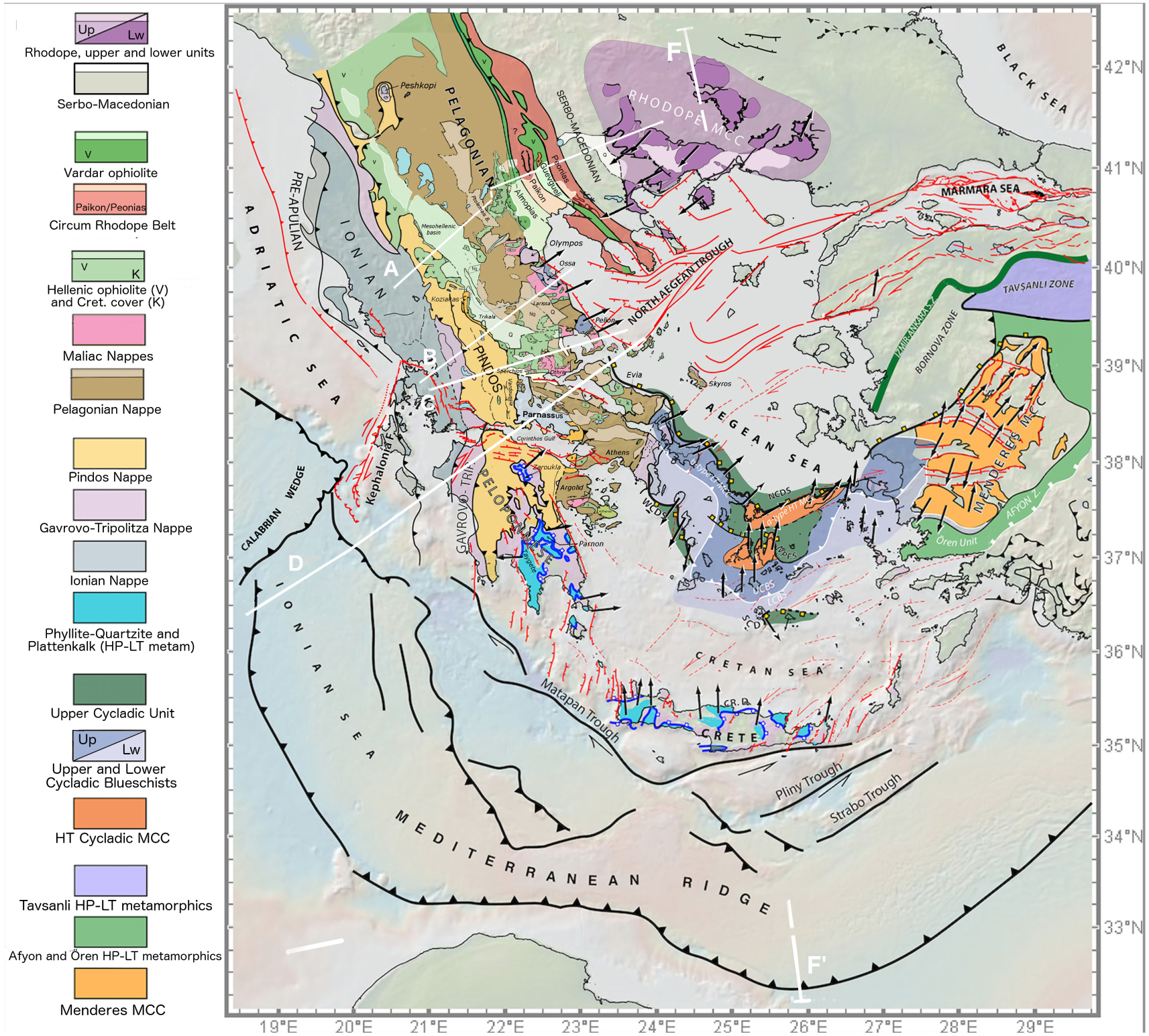

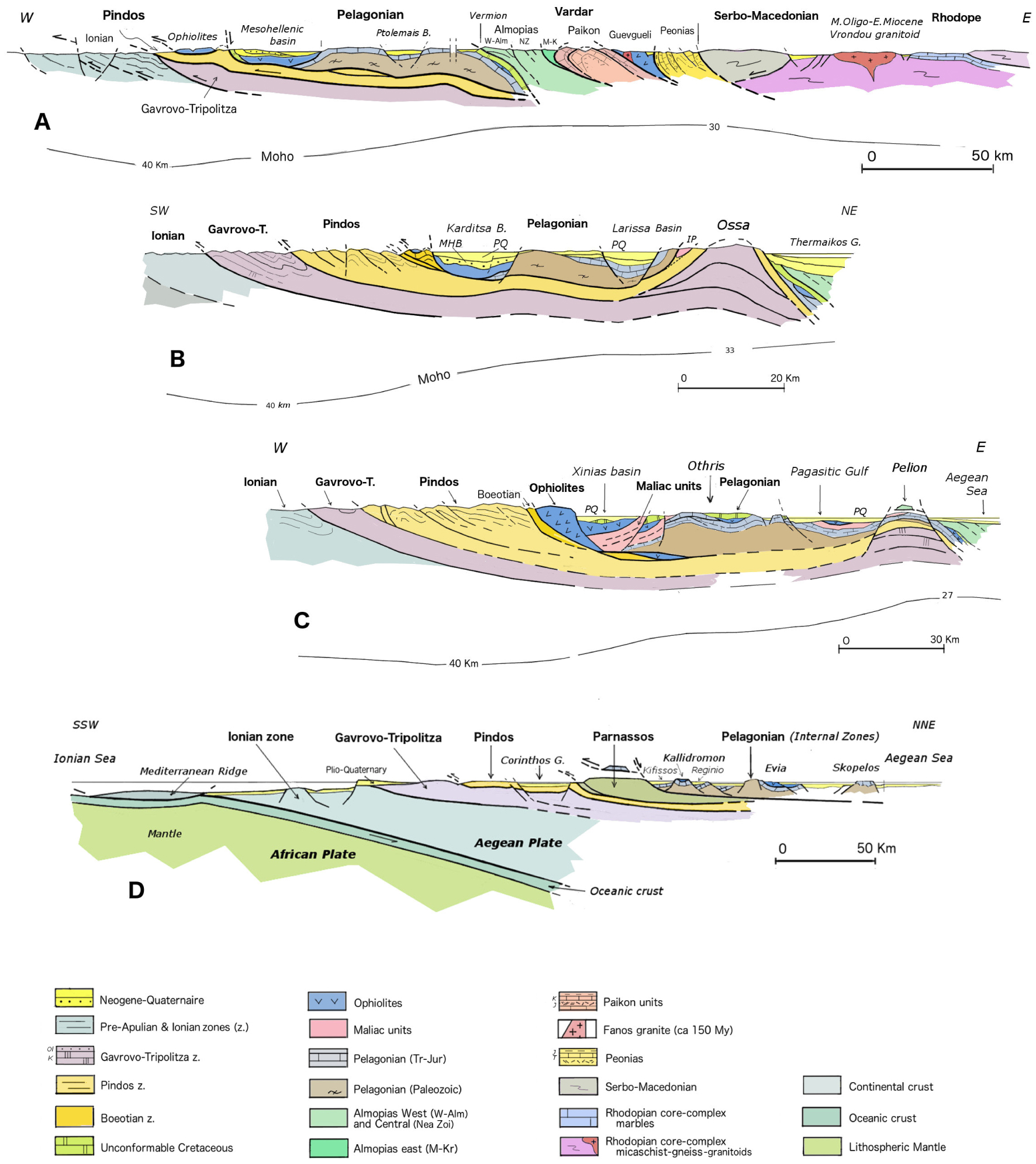

The Hellenides and the Aegean domain cover the entire Greece and extends eastward onto the Anatolian side of the Aegean Sea in the Taurides and the Menderes massif. The western Hellenides form a rather continuous massif at high altitude resting on a ca. 40–45 km thick continental crust [Makris et al. 2013]. In the eastern part of the belt, NW–SE striking reliefs, including Mount Olympos (2918 m) alternate with recent sedimentary basins. Further east, the Aegean back-arc basin is characterised by the Cyclades, Dodecanese, Eastern Aegean Islands, or Crete. The continental crust is progressively thinned toward the Aegean domain.

This spatial organisation results from the superimposition of several orogenic events: (i) the Jurassic obduction of the Tethyan (Maliac) oceanic lithosphere [e.g. Bernoulli and Laubscher 1972; Dercourt 1970; Ferriere 1972, 1982; Hynes et al. 1972; Jacobshagen 1986; Smith et al. 1975]; (ii) an Eocene collision between the Adria (Apulia) to the SW and the European domain to the NE (Figures 1 and 2) [Aubouin 1959; Jacobshagen 1986; Schmid et al. 2020]; (iii) A more recent, mainly Miocene extension with a stretching amount increasing toward the east, reworking the structural pattern inherited from the collision.

Tectonic map of the Hellenides and of the Aegean region [modified after Jolivet et al. 2021, references within]. (A–D) location of cross-sections Figure 2; FF′: upper cross-section Figure 6. The light colours at the top of the cartouches represent the recent sedimentary levels deposited on the concerned basement in darker colours.

Cross-sections across the Hellenic belt. (A–D) Location Figure 1. (A) In northern Greece from Rhodope to Pindos-Ionian Zones through the Vardar and Pelagonian Internal Zones; (B) cross-section in the Pelagonian domain and Plio-Quaternary basins within the Internal Zones with the Ossa window showing External units underneath; (C) cross-section in the Internal Zones showing the Jurassic syn-obduction Maliac units; (D) cross-section across the Pelagonian and Parnassus Zones to the current subduction zone of the eastern Mediterranean Sea.

This late tectonic episode results from the change in subduction dynamics and the beginning of slab retreat in the Late Eocene [Jolivet and Faccenna 2000]. The western Hellenides, corresponding to External Zones of the belt, were tectonized only during the Tertiary while the eastern Hellenides, where the obduction episode is recorded, form the Internal Zones [Brunn 1956].

2.1. Regarding the Hellenides

The western Hellenides or External Zones are made up of a stack of nappes derived from the eastern margin of the Adria block. This apparent simplicity made this sector ideal for the first important tectonic syntheses. The main isopic zones and nappes were deciphered as early as in the 50–60s, notably by Aubouin [1959] (Figures 1 and 3). Going from west to east, we first find the pre-Apulian Zone, a carbonate platform followed by the Ionian Zone comprising subsiding basin since the Lias-Dogger, and the Gavrovo-Tripolitza Zone, a platform until the Middle-Late Eocene. Further east, the Pindos Zone represents a deep basin from the Triassic onward, including syn-rift lavas and finally an Eocene flysch [Brunn 1956; Aubouin 1959] (Figure 3). Later on, numerous stratigraphic and structural features were recognised [Degnan and Robertson 1998; Doutsos et al. 2006; Faupl et al. 1998; Fleury 1980; IGRS-IFP 1966; Konstantopoulos and Zelilidis 2012; Pe-Piper and Piper 1984; Thiébault 1982]. Uncertainties persist on the nature of the Pindos Zone, whether a continental crust, more or less thinned [Bortolotti et al. 2013; van Hinsbergen et al. 2020; Schmid et al. 2020; Thiébault 1982], or an oceanic crust [Bonneau 1982; Menant et al. 2016a, b] interpreted as the root of the supra-Pelagonian ophiolites [Dercourt 1970; Dilek et al. 2007; Rassios and Smith 2000; Jones and Robertson 1991; Saccani and Photiades 2004; Smith et al. 1975].

Stratigraphic logs related to the Hellenic isopic zones. (1–6) Limestones (lmst); (1) benthic (platform), (2) oolithic (down) to conglomerates (up); (3) fine-grained (down) and siliceous (up); (4) Ammonitico Rosso (Peonias); (5) alternating calcarenites (up, triangles) and siliceous lmst (down, dashes); (6) siliceous fine-grained lmst and calcarenites (up), marls and sandstones (down); (7) radiolarites (down: pelitic); (8) argillaceous beds (down), argillaceous sandstones (up); (9) sandstones with siliceous conglomerates (triangles, down); (10) conglomerates (MHB); (11) flyschs; (12) ophiolitic mélanges; (13–16) volcanism; (13) rhyolites; (14) basaltes; (15) andesites; (16) Triassc syn-rift pillow-lavas (violet); (17–19) ophiolites (green); (17) pillow-lavas; (18) gabbros, dolerites; (19) peridotites; (20) metamorphic basements; (21) main unconformities; (22) Thrusts.

Nappe stacking in the Hellenides exhibits quite a regular NW–SE strike that can be followed northward up to the Dinarides [Aubouin 1959]. This simple pattern is locally perturbed by the presence of the Parnassus Zone, an additional platform sandwiched between the Pindos and the Internal Zones, observed between the Corinth and Sperchios rifts (Figures 1 and 2D) [Celet 1962]. Similarly, this Hellenic strike is disturbed in Crete and Peloponnese due to the presence of tectonic windows revealing the substratum made of the Gavrovo-Tripolitza Nappe [Jolivet et al. 1996; Jolivet and Brun 2010; Jolivet et al. 2010b; Seidel et al. 1982; Theye and Seidel 1991; Theye et al. 1992; Thiébault 1982]. These windows are metamorphic core complexes formed during syn-orogenic exhumation and post-orogenic extension, accommodated by the north-dipping Cretan Detachment. Crete and the Peloponnese are underthrust by the subducting oceanic lithosphere of the Eastern Mediterranean located south of the Adria block. Further to the NW, in the Hellenides, continental collision is still active. The transition from oceanic subduction to continental collision is accommodated by the dextral Kephalonia transfer fault [Özbakır et al. 2020] (Figure 1).

To the NE, the Serbo-Macedonian and Rhodope massifs belong to the European continental plate. The area used to be referred to as the “Zwischengebirge” [Kossmat 1924].

At present, the Rhodope massif is a large metamorphic core complex (MCC) reworking a nappe stack emplaced during the Tertiary Alpine orogeny with a HT-LP metamorphism locally reaching melting conditions [Burg 2011; Burg et al. 1996; Gautier et al. 2017; Wawrzenitz et al. 2015]. Units showing HP-LT metamorphism are present [Liati and Mposkos 1990; Liati and Seidel 1996], even remnants of UHP-LT metamorphism with the preservation of coesite [Kostopoulos et al. 2000]. Several low-angle detachments have been found within the Rhodope such as the Nestos shear zone [Brun and Sokoutis 2007; Burg 2011]. In contrast, the same structure has been interpreted as a thrust by Gautier et al. [2010, 2017]. The MCC was exhumed underneath several SW-dipping detachments, including the Strymon Valley Detachment [Dinter and Royden 1993] and the Kerdilion Detachment further to the west, active from the Eocene (42 Ma) to the Late Oligocene (24 Ma) [Brun and Sokoutis 2007]. For a more exhaustive description of metamorphic units in the Rhodope, see [Brun and Sokoutis 2007; Burg 2011; Kounov et al. 2015; Krenn et al. 2010; Kydonakis et al. 2014; Liati and Seidel 1996; Schmid et al. 2020].

The Internal Zones of Pelagonian and Vardar domains develop between the Pindos Zone and the Rhodopes (Figure 1). The Pelagonian is a fundamental unit in the Hellenides, bounded by major Tertiary thrusts. It extends northward across Albania and to ex-Yugoslavia [Aubouin et al. 1970]. This domain is rich in metamorphic rocks assumed of Paleozoic or older ages [Anders et al. 2006; Schenker et al. 2014, 2015]. The Pelagonian calcareous cover, paleontologically dated from Triassic to Jurassic [Brunn 1956; Celet and Ferriere 1978 and references therein; Ferriere 1982], is overthrusted by ophiolitic nappes among which the well-known Vourinos unit is unconformably overlain by Late Jurassic–Cretaceous deposits (Figure 3). As an isopic zone, the Pelagonian is only defined for the Triassic–Mid-Jurassic, before obduction [Celet and Ferriere 1978]. This domain bordering the Pindos Zone was initially considered in Aubouin’s [1959] Geosyncline model as the “eugeoanticline”, an undeformed tectonic unit during the Alpine orogenic cycle.

A first revolution came with the discovery of the Olympos tectonic window within the Pelagonian domain [Godfriaux 1962, 1968] witnessing a major Alpine thrust above a platform sequence attributed to the Gavrovo-Tripolitza (GT) Zone [Fleury and Godfriaux 1974]. Similar structures were described further south such as the Ossa window [Derycke and Godfriaux 1978] and the Almyropotamos one in Evia [Dubois and Bignot 1978; Katsikatsos et al. 1976]. The Olympos window shows additional tectonic units between the Upper Pelagonian nappe and the lower GT limestones, the Infra-Pierian Unit, locally containing ophiolites, and just below, the blueschist-facies Ambelakia unit attributed to the Pindos Zone partly because of its structural position [Hinshaw et al. 2023; Schmitt 1983; Schermer 1990]. The analyses of metamorphic terranes present in the Olympos window have revealed consistent Eocene ages of the blueschists as well as in the Pelagonian, corresponding to the period of subduction and stacking of these nappes [Lips et al. 1998; Schermer 1990, 1993; Schermer et al. 1990]. Other blueschist-facies units have been described in an equivalent structural position below the Pelagonian, the Makrinitsa Unit in the Pelion [Ferriere 1982] and the Styra–Ochi Unit in Evia [Katsikatsos et al. 1976].

These HP-LT units are the lateral equivalent of the Cycladic Blueschists [Jolivet et al. 2004a, b]. Outcrops of platform deposits similar to the GT series in the Cyclades (Tinos, Samos, Naxos), sometimes attributed to the so-called Basal Unit [e.g., Ring et al. 2010, 2011] are probably the equivalent of these tectonic windows in the Internal Zones of the Hellenides [references in Jacobshagen 1986; Avigad and Garfunkel 1989; Jolivet et al. 2004b; Schmid et al. 2020].

A large sedimentary basin, the Mesohellenic molassic basin (MHB) developed in a piggy-back mode on top of the Pelagonian–Ophiolitic domain [Ferriere et al. 2004] from the Late Eocene to the Middle Miocene [Brunn 1956; Aubouin 1959; Doutsos et al. 1994; Zelilidis et al. 2002; Ferriere et al. 1998, 2004, 2013]. The subduction of the Pindos and GT zones underneath the Pelagonian was coeval with the successive sedimentary sequences of the MHB. After the Miocene, the Pelagonian was reworked by a major phase of extension observed on the continent (i.e., Trikala and Larissa basins) or in the Aegean domain where extension scattered the Upper Cycladic Nappe from the Northern Cyclades to Crete [Bonneau 1984; Jolivet et al. 2004b].

The concept of obduction [Coleman 1971], a second revolution, changed the interpretation of the Pelagonian domain. It led to consider the ophiolites as nappes remnants of oceanic lithosphere instead of mere intruding magmatic bodies later overthrust as postulated by the Geosyncline model.

Brunn [1956] and Moores [1969] published pioneer observations of the petrology of these ophiolites in the northern Pindos and the Vourinos massifs with a complete succession from basal harzburgites, then gabbros and dolerite dykes, to lavas and finally pelagic sediments.

Before the onset of Plate tectonics, Brunn [1959] compared these ophiolites with an ocean floor. He further noticed the presence of a reverse metamorphic gradient with lenses of amphibolites on top of greenschists underneath the ophiolites.

The Othris ophiolites (Figures 1 and 2) allow reconstructing the Maliac Ocean, a major part of the Tethys Ocean located between the Pelagonian and the Rhodope continental domains [Ferriere 1976b]. Between the ophiolitic nappes and the parautochtonous Pelagonian domain, several syn-obduction units represent the Triassic–Mid Jurassic western passive margin of the Maliac Ocean [Ferriere 1972, 1974, 1982, 1985; Ferriere et al. 2016 and references therein, Hynes et al. 1972; Smith et al. 1975], including the proximal margin, also present in Argolid [Ferriere 1974; Baumgartner 1985; Ferriere et al. 2016] and mostly the distal margin is not observed in other sectors of the Hellenides [Ferriere 1974, 1982] (Figure 3). Tithonian–Early Cretaceous Beotian Flysch [Celet et al. 1976a, b; Nirta et al. 2018], deposited to the west of the ophiolite units, is interpreted as a syn-obduction foreland basin, supporting the rooting of the ophiolites to the east of the Pelagonian, i.e., in the Maliac Ocean, instead of postulating a Pindos origin as formally proposed [see discussion in Ferriere et al. 2012, 2016, and references therein].

The Vardar Zone is a complex domain, that underthrusts the Serbo-Macedonian domain to the east and overthrusts the Pelagonian to the west (Figures 1 and 2). Mercier [1968] distinguished several isopic/tectonic zones, namely from SW to NE: the Almopias and Peonias units, deep basins separated by the Paikon platform. An additional pre-Peonian unit, containing the Guevgueli ophiolites, is sandwiched between the Paikon and Peonias units (Figure 1). Kauffmann et al. [1976] elaborated the content of the Peonias series and Kockel [1986] replaced the Pre-Peonias and Peonias by the “Guevgueli-Stip Axios ophiolites” respectively; and defined the “Circum Rhodope Belt”. Mercier [1968] soon pointed out to the imprint of Tertiary tectonics in the Vardar domain. Various structural interpretations of the Paikon (cf. infra Section 4.5.2) have been proposed [Brown and Robertson 2003; Ferriere et al. 2001; Mercier 1968; Vergely and Mercier 2000].

The interpretation of the Vardar domain and its ophiolites benefited from the obduction model, too. Indeed, Bernoulli and Laubscher [1972] located the origin of the supra-Pelagonian ophiolites in the Central Tethys to the east that’s to say from the Vardar domain. They were then joined by Dercourt [1972], first in favour of a Pindos origin [Dercourt 1970], then by numerous authors [Baumgartner 1985; Bortolotti et al. 2013; Ferriere 1982; Ferriere et al. 2012, 2016; Schmid et al. 2008] with the notable exception of most Anglo-Saxon authors. The Tethyan (Maliac) suture, where these ophiolites come from, would thus be located in the Almopias domain with its highly diversified series (Figure 3) [Mercier and Vergely 1984; Migiros and Galeos 1990; Saccani et al. 2015; Sharp and Robertson 2006; Stais et al. 1990]. Triassic pre-obduction radiolarites, witnessing a deep basin (probably oceanic) have indeed been observed in the Almopias sector [Unité de Vryssi, Stais et al. 1990; Stais and Ferriere 1991]. An important issue remains debated: the width of the oceanic domain left after obduction in this domain. Some authors draw a wide residual ocean in this region [e.g., Menant et al. 2016a, b; Stampfli and Borel 2002].

Middle and Late Jurassic rhyolites and andesites in the Paikon zone led several authors to consider the existence of a volcanic arc related to the eastward subduction of the Tethys Ocean (Maliac) [Bortolotti et al. 2013; Ferriere and Stais 1995; Ferriere et al. 2012, 2015, 2016; Mercier et al. 1975; Robertson 2012]. Hence, these authors conclude that the Middle and Late Jurassic Guevgueli ophiolites [Danelian et al. 1996; Kukoc et al. 2015], east of the Paikon, originated as a back-arc basin. Geochemical data confirm this attribution [Saccani et al. 2008]. Additional studies integrating data obtained from zircons sampled in the metamorphic sectors further to the SE, led authors [Bonev et al. 2015] to propose the involvement of several subduction zones in the evolution of the Paikon arc, the Guevgueli ophiolites and their equivalents. The Peonias series have been described in detail, including those of the Chalkidiki Peninsula [Bonev et al. 2015; Ferriere and Stais 1995; Kauffmann et al. 1976; Mercier 1968; Stais and Ferriere 1991]. They represent the Triassic–Jurassic eastern margin of the Maliac ocean, inverted during Cenzoic tectonics [Ferriere and Stais 1995; Ferriere et al. 2016]. Within the Peonias series, Triassic lavas and facies transitions witness the syn-rift period [Asvesta and Dimitriadis 1992; Ferriere and Stais 1995] coeval with the syn-rift of the west-Maliac margin, one argument in favour of these two domains being the conjugate margins of that ocean [cf. Ferriere et al. 2016].

2.2. Aegean domain

The first-order structure of the Aegean domain results from a change in subduction dynamics some 30–35 Ma ago when slab retreat started as a result of the Africa–Eurasia collision [Jolivet and Faccenna 2000]. The consequence was the opening of several back-arc basins, among them the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Aegean Sea [e.g., Jolivet et al. 2013; Le Pichon and Angelier 1979, 1981].

The first observations in this last region showed some similarities with the Internal Zones of the Hellenides and postulated possible correlations [Bonneau 1984; Jacobshagen 1986]. The definition of the Cycladic Blueschists Nappe [Blake et al. 1981] was an important milestone to integrate this region into the regional tectonic framework, showing tectonic units exhumed from the depth of the subduction interface [Altherr et al. 1979; Bonneau 1982, 1984; Bonneau and Kienast 1982; Bonneau et al. 1980; Hecht 1984; Okrusch et al. 1978] but finding a regional logic was difficult. A synthetic account of available observations at that time in the Attic-Cycladic massif can be found in Bonneau [1984] and Jacobshagen [1986]. The same pile of nappes observed in the continental Hellenides is recognised at this period with the Pelagonian Unit at the top [e.g., Laskari et al. 2022] with basement lithologies and ophiolites, locally named the Upper Cycladic Unit, devoid of any evidence of Eocene HP-LT metamorphism.

This unit overlies the Cycladic Blueschists (Figures 4–6), equivalent to the Ambelakia Unit observed near Mount Olympos, and the basal platform series similar to the External Zones (Gavrovo-Tripolitza), with either HP-LT metamorphic parageneses reaching the blueschist-facies or the eclogite facies (Syros, Sifnos, Tinos, Samos) or HT-LP ones locally reaching anatexis (Paros, Naxos, Mykonos) [Altherr et al. 1979, 1982; Andriessen et al. 1979; Blake et al. 1981; Bonneau and Kienast 1982; Hecht 1984; Jansen and Schuilling 1976; Okrusch et al. 1978; Papanikolaou 1977, 1980].

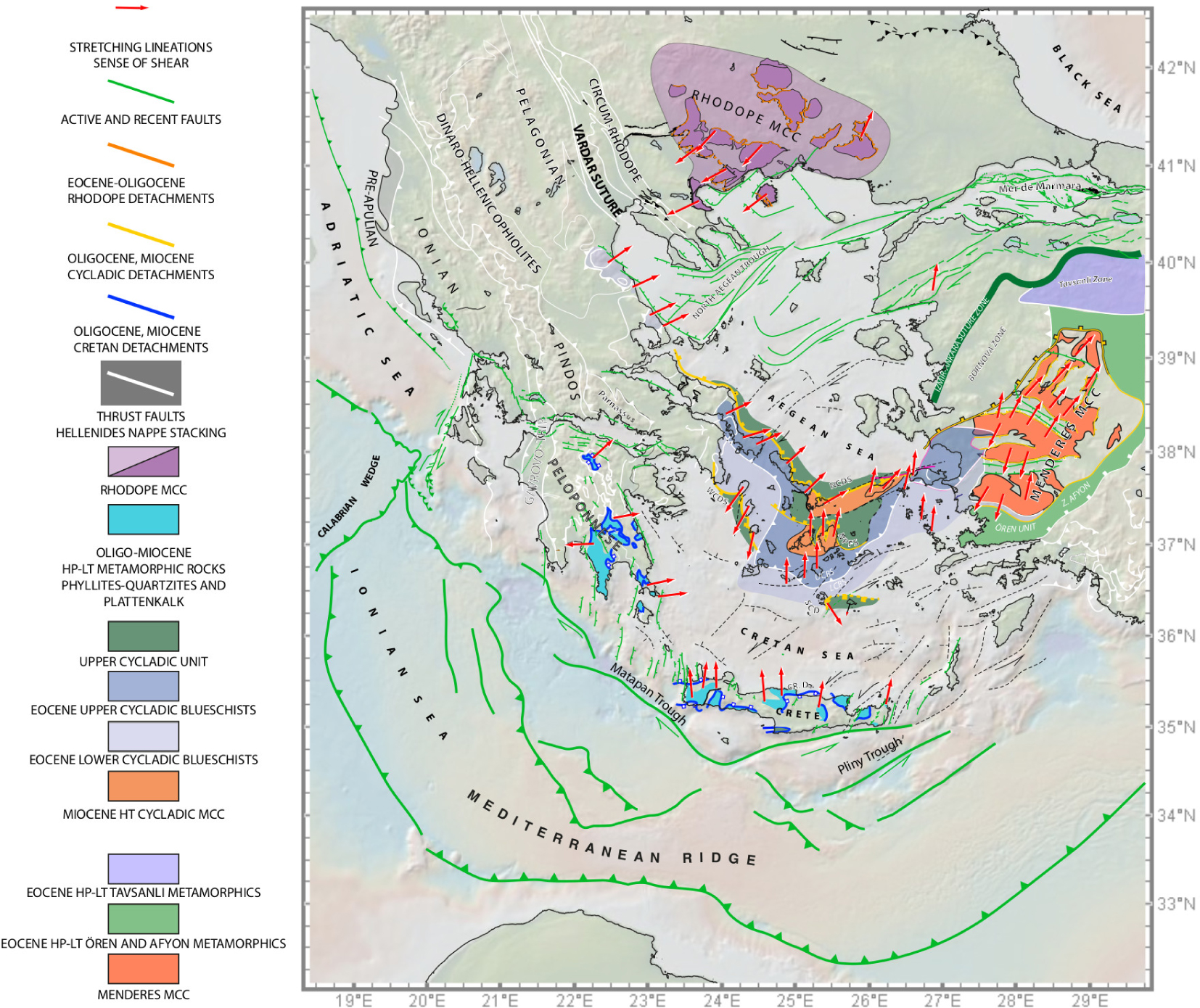

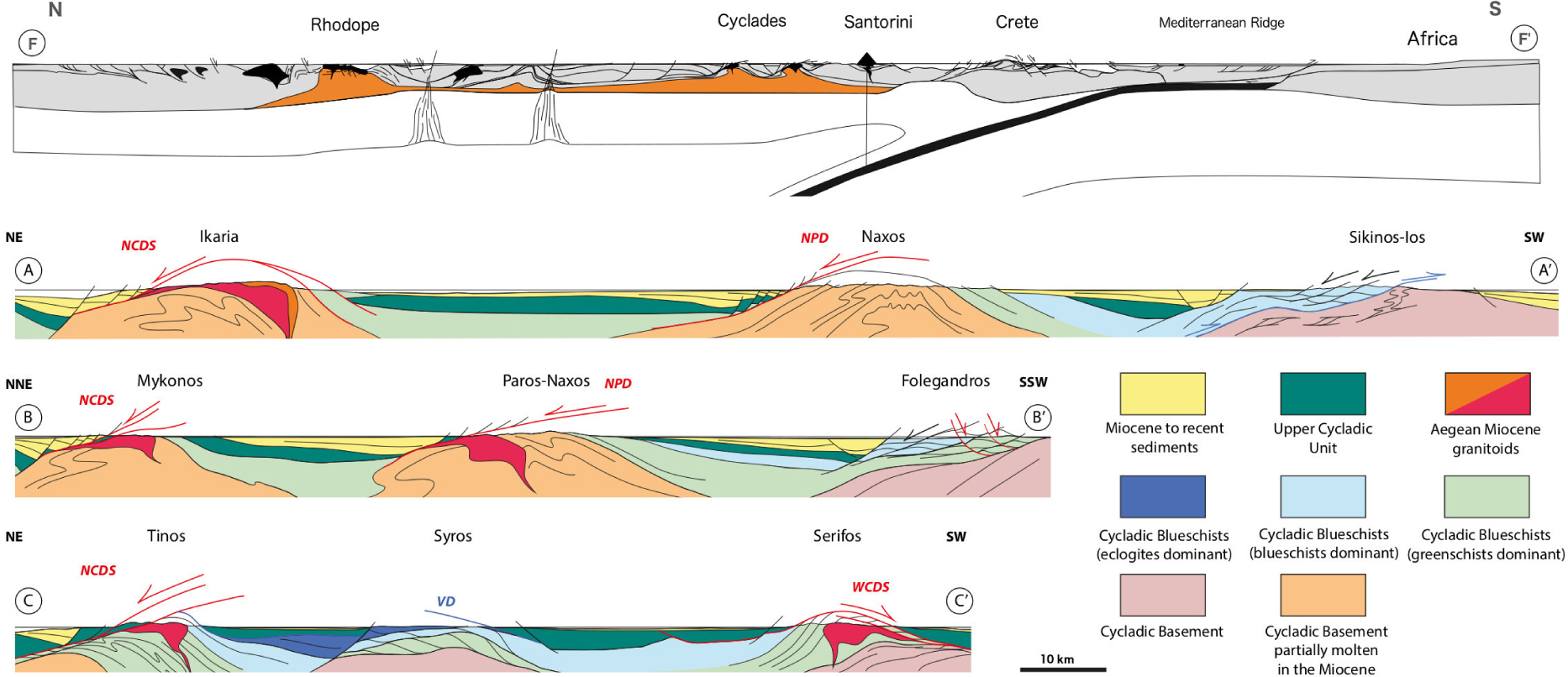

Metamorphic core complexes in the Aegean region from the Rhodope to Crete and the Menderes. The main detachments accommodating their exhumation are represented with different colours depending upon their timing of activity. Red arrows represent the kinematics of ductile and brittle deformation in the shear zones observed in the footwalls. NCDS: North Cycladic Detachment System, NPFS: Naxos–Paros Fault System, WCDS: West Cycladic Detachment System, SCD: South Cycladic Detachment, CR D: Cretan Detachment, UCSB: Upper Cycladic Blueschists, LCSB: Lower Cycladic Blueschists.

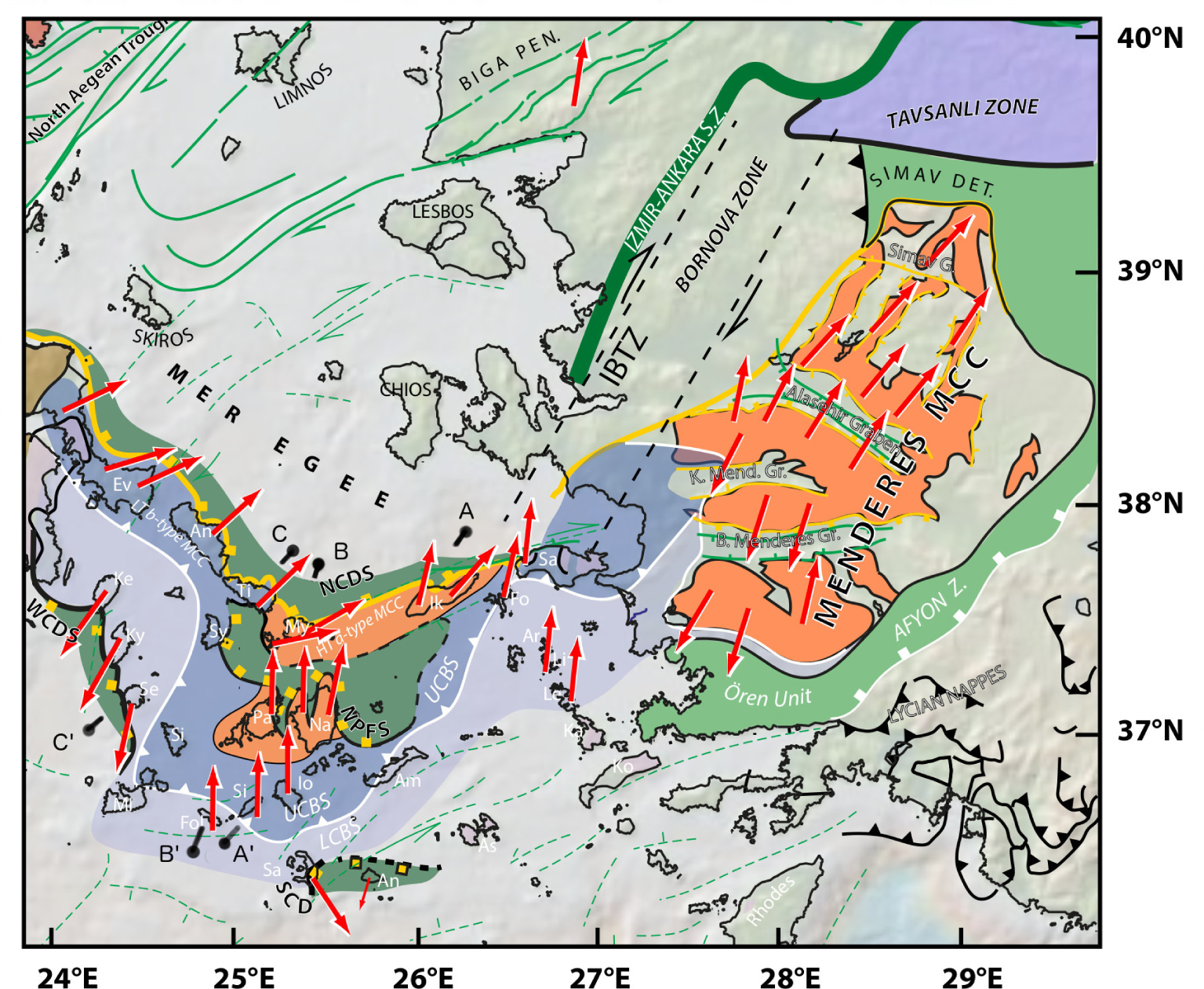

Detailed map of the Cycladic MCC and the Menderes Massif. NCDS: North Cycladic Detachment System, NPFS: Naxos–Paros Fault System, WCDS: West Cycladic Detachment System, SCD: South Cycladic Detachment, CR D: Cretan Detachment, UCSB: Upper Cycladic Blueschists, LCSB: Lower Cycladic Blueschists. IBTZ: Izmir-Bornova Transfer Zone, Ev: Evia, An: Andros, Ti: Tinos, My: Mykonos–Delos–Rhenia, IK: Ikaria, Sa: Samos, Sy: Syros, Pa: Paros, Na: Naxos, Ke: Kea, Ky: Kythnos, Se: Serifos, Si: Sifnos, Fol: Folegandros, Si: Sikinos, Io: Ios, Fo: Fourni, Ar: Arki: Li: Lipsi, Le: Leros, Ka: Kalimnos, Ko: Kos, Mi: Milos, Sa: Santorini, An: Anafi, As: Astipalea. AA′, BB′ and CC′: cross-sections Figure 6.

Cross-sections through the Aegean region and zoom on the Cycladic MCC. Upper: a simplified N–S section through the entire back-arc region after Jolivet and Brun [2010]; location on Figure 1 (FF′); the orange domain represents the part of the crust partially molten during extension. Lower: AA′, BB′, CC′, three sections through the main Aegean MCC and corresponding detachments after Jolivet et al. [2015]; location on Figure 5.

The structural position of the Cycladic Blueschists and their Eocene metamorphic ages (50–35 Ma) make them lateral equivalents of the Pindos Nappe [Bonneau 1984; Jolivet et al. 2004a, b].

Later works were devoted to the detailed description of the HP-LT parageneses in the Cycladic Blueschists and associated deformation and time constraints [Bröcker and Enders 1999; Bröcker et al. 2013; Laurent et al. 2016; Parra et al. 2002; Trotet et al. 2001a, b; Uunk et al. 2022; Wijbrans and McDougall 1988; Wijbrans et al. 1993]. Recent studies in the HP-LT units also evidenced the existence of two main units with distinct P–T evolution. The eclogite-bearing Cycladic Blueschists of Syros, Tinos and Sifnos belong to the Upper Cycladic Blueschists Nappe, while the blueschists of Kea or Kythnos, that never reached the eclogite facies belong to the Lower Cycladic Blueschists Nappe, the contact going across the basement of Milos [Grasemann et al. 2017; Roche et al. 2019] (Figure 5).

The seminal paper by Lister et al. [1984] changed the game. In Naxos, these authors recognised a cordilleran-type metamorphic core complex (MCC) that they related to the extension leading to the formation of the Aegean Sea. This was the first of a long series of studies systematically describing the Aegean MCCs and their detachments. These low-angle normal faults and the associated ductile and brittle deformation in the footwalls were studied in great detail by several teams. The main detachments (Figures 4 and 5) are the NE-dipping North Cycladic Detachment System (NCDS) [Avigad and Garfunkel 1989; Jolivet et al. 2010a] fringing the northern Cyclades and Eastern Aegean Islands (Andros, Tinos, Mykonos, Ikaria) and extending to the NW all the way to offshore Olympos and to NE into the Simav Detachment, the SW-dipping West Cycladic Detachment System (WCDS) observed on the SW Cyclades (Kea, Kythnos, Serifos) [Grasemann et al. 2012], the S-dipping South Cycladic Detachment or Santorini Detachment mainly observed on Santorini [Ring et al. 2011; Schneider et al. 2018] and the N-dipping Paros–Naxos Fault System (NPFS) [Bargnesi et al. 2013; Gautier et al. 1993; Buick 1991; Urai et al. 1990].

The kinematics of these detachments and of the ductile-to-brittle deformation in the footwall show a simple pattern with N–S extension in the south changing to NE–SW toward the NE [Faure and Bonneau 1988; Faure et al. 1991; Gautier and Brun 1994; Gautier et al. 1993; Grasemann et al. 2012; Jolivet et al. 2004a, b, 2013; Roche et al. 2019]. These major detachments are the main structures accommodating crustal thinning in the Aegean Sea in the Oligocene and Miocene, with typical offsets reaching several tens of kilometers or even 70–100 for the NCDS [Brichau et al. 2006, 2007, 2008; Jolivet et al. 2010a, b; Menant et al. 2016a, b].

The Aegean Sea is one of the key regions where the activity of detachments formed at a low-angle was demonstrated [Jolivet et al. 2010a; Lacombe et al. 2013; Mehl et al. 2005]. The late stages of extension were accompanied by the intrusion of granitic plutons or dykes in Tinos, Mykonos, Delos, Rhenia, Ikaria, Samos, Paros, Naxos, Serifos and in Lavrion on south Attica. These plutons interacted with the activity of the detachments [Faure and Bonneau 1988; Faure et al. 1991; Lee and Lister 1992]. Detailed studies of these interactions showed that the internal geometry of these plutons, from the flow of magma to the sub-solidus deformation in the vicinity of the detachments, were controlled by the detachment and the associated stress regime [Rabillard et al. 2018; Jolivet et al. 2021]. The detachments and the MCCs are also observed outside the Aegean Sea, in the Rhodope massif to the north [Brun and Sokoutis 2007; Burg 2011] and in the Menderes massif to the east [Bozkurt and Park 1994; Bozkurt and Oberhänsli 2001; Bozkurt and Satir 2000; Gessner et al. 2001; Hetzel et al. 1995; Ring et al. 1999] showing the imprint of back-arc extension over a wide region (Figures 1 and 4). Extension was recorded as far south as the island of Crete where the exhumation of the HP-LT Phyllites–Quartzites and Plattenkalk (Ionian nappes) was accommodated by syn-orogenic detachments (the Cretan Detachment) obeying to the same simple pattern of N–S extension during the Miocene as further north in the Cyclades [Jolivet et al. 1994a, b, 1996; Fassoulas et al. 2004; Seidel et al. 2007; Grasemann et al. 2019].

Synthetic models were proposed at various stages of the progressive understanding of the geological context. Bonneau and Kienast [1982] described the progressive formation of the Cycladic Blueschists; Jolivet et al. [2003], van Hinsbergen et al. [2005a, b] and Grasemann et al. [2017] showed the progressive stacking of nappes during the northward subduction of Apulia and then the eastern Mediterranean oceanic lithosphere. Jolivet and Brun [2010], Ring et al. [2010] and Grasemann et al. [2012] described the progressive subduction and exhumation of the Cycladic Blueschists from underneath the detachments; Menant et al. [2016a, b] did the same but in 3D. At a large scale, the Hellenides and the Aegean region were integrated in paleogeographic reconstructions of the Tethys Ocean from the Triassic to the Present [Laubscher and Bernoulli 1977; Biju-Duval et al. 1977; Dercourt et al. 1986; van Hinsbergen et al. 2020; Stampfli and Borel 2002].

3. Mediterranean period

Since this paper is mainly a synthesis of the evolution of the Hellenides and its geodynamic drivers, we only focused on the main observations that constrain the origin of forces driving back-arc extension in the Aegean region. As presented above, the Aegean extension and resulting crustal thinning were coeval with subduction and formation of HP-LT metamorphic parageneses in subducted units during the Oligocene and Miocene, followed by their exhumation in the plates interface of the Hellenic subduction after 35 Ma [van Hinsbergen et al. 2005a, b; Jolivet and Brun 2010; Jolivet et al. 1996, 2010b; Seidel et al. 1982; Theye and Seidel 1991; Theye et al. 1992]. The HP-LT units of the Phyllite–Quartzite nappe (Nappe des Phyllades in French) and the underlying Plattenkalk Nappe (Ionian Nappe in French) were parts of the southern margin of the Adria (Apulia) block, which also includes the Upper and Lower Cycladic Blueschists Units subducted and accreted earlier during the Eocene. They were exhumed underneath the Cretan Detachment at the same time as the Aegean detachments were active [Jolivet et al. 1996, 2013] during the southward retreat of the African slab. This behavior is typical of the Neogene Mediterranean subduction and collision zones, from the Gibraltar arc, the Apennines all the way to the Hellenic subduction. The same Cretan Detachment has been recognised in the Peloponnese (Figures 1 and 4), as far north as the Zarouchla window just south of the Corinth Rift [Jolivet et al. 2010b; Trotet et al. 2006]. The P–T conditions and paths recorded by the Phyllite–Quartzite Nappe in Crete and the Peloponnese show a gradient from east to west, with a colder P/T gradient in the east and a warmer one in the west, with a difference of about 100 °C for the pressure peak. This has been attributed to differences in kinematic boundary conditions of the subduction zone by Jolivet et al. [2010b]. Crete, where the P/T gradient is the coldest, is located along the transect of the Aegean domain that has seen the largest and fastest extension, because of fast slab retreat. This would have created a more opened subduction channel where crustal rocks are first subducted and then exhumed. This, in turn facilitated the two-way circulation of rock material and thus avoided substantial heating. This mechanism was probably active also during the Tethyan period, before 35 Ma, when the Cycladic Blueschists were subducted and exhumed further north. Slab retreat was slower during this period [Jolivet and Brun 2010] and the metamorphic parageneses show warmer conditions than in Crete with a differential of about 100 °C.

Further north, in the Cyclades, in the Internal Zones of the Hellenides, in the southern part of the Rhodope massif and in the Menderes Massif (Figures 1 and 4), extension was accommodated by the activity of the detachments reported above and the exhumation of MCCs [Gautier and Brun 1994; Jolivet and Patriat 1999; Jolivet et al. 2004a, b; Ring and Layer 2003; Bargnesi et al. 2013; Grasemann et al. 2012; Roche et al. 2019]. Two types of MCCs (Figures 5 and 6) are recognised, depending on the P–T conditions of deformation [Jolivet et al. 2004a, b]. Cold MCC are those where the Eocene HP-LT parageneses of the Cycladic Blueschists are best preserved, Andros, Tinos, Syros, Sifnos, Kea, Kythnos, Amorgos, Samos. Hot MCC are those where the Eocene HP-LT parageneses have been almost totally erased by later high-temperature imprint, Naxos, Paros, Mykonos–Delos–Rhenia, Ikaria. The shapes of P–T paths are drastically different with a clear excursion toward high temperature along the retrograde path in hot MCC, reaching the conditions of anatexis. The two extreme behaviors can be illustrated by the examples of Syros (or Sifnos) on the cold side and Naxos on the hot side. In the best-preserved units of Syros, the retrograde path traveled along a cold gradient, parallel to the prograde path, without any loop toward high temperature. Intermediate shapes of P–T paths have been retrieved from the MCCs of Andros and Tinos, as well as from the deepest units of Syros, that show some strong retrogression in the greenschist-facies. The retrograde path starts along a cold gradient during the Eocene until the pressure of 9–10 kbar reached at approximately 37 Ma. An isothermal heating is then observed until ∼35 Ma and exhumation resumes along a warmer path. These two different gradients in fact correspond to the succession of the Tethyan and Mediterranean periods. In the Eocene, the Cycladic Blueschists were exhumed within the subduction channel. This process is referred to syn-orogenic exhumation, just like it occurred in Crete later on, in the Oligocene and Miocene. From the Late Eocene to the Miocene, exhumation was accommodated by post-orogenic detachments, responsible for crustal thinning in the back-arc regions associated with a higher heat flow. Syn-orogenic exhumation had then migrated southward in Crete and the Peloponnese, following slab retreat [Jolivet et al. 1994b; Jolivet and Brun 2010].

Recent studies by Lamont et al. [2020] and Searle and Lamont [2020] present a different interpretation where post-orogenic extension is more recent and is mostly a low-temperature process. In their interpretation these authors consider that most of the deformation in the deep parts of the Naxos MCC are related to the shortening period, before the Aegean extension that would not have started before 15 Ma. In that sense they join the interpretation of Ring et al. [2010] dating the inception of extension at ∼21 Ma, which is the age of the first marine sediments deposited in the Aegean Sea. Answering this debate would necessitate more detailed studies, but we can already state that the 35 Ma age we propose for the transition from syn-orogenic to post-orogenic tectonics is based upon the fast southward migration of the magmatic arc, which imposes a component of back-arc extension at that period. It is also based upon the ages of the greenschist-facies shearing deformation underneath the NCDS in Tinos and Andros [Laurent et al. 2017]. The study of the deep core of the Mykonos–Delos–Rhenia MCC shows that the migmatites observed there were molten and deformed at the same time as the Middle Miocene granite plutons intruded [Jolivet et al. 2021]. The Naxos pluton intruded the high-temperature dome once it had already been exhumed and cooled from the depth of anatexis [Jansen and Schuilling 1976; Urai et al. 1990; Gautier et al. 1993; Bessiere et al. 2018] by the activity of the top-to-north Paros–Naxos detachment, which was thus active before, while the core rocks were partially molten and sheared toward the north. One can observe in all these MCC a continuum of shearing and exhumation, either top-north or top-south [Jolivet et al. 2013; Grasemann et al. 2012; Roche et al. 2019].

Slab retreat is thus independently documented by the southward migration of magmatic products from the Late Eocene to the present [Fytikas et al. 1984; Jolivet et al. 2004b]. Another trend of migration is observed regarding Miocene granitic intrusions. The oldest Aegean plutons are found in Ikaria [16 Ma, Bolhar et al. 2010, 2012] associated with migmatites [Beaudoin et al. 2015]. During about 8 Ma, younger plutons were emplaced further to the southwest and south, the youngest being found in the Lavrion MCC some 8 Ma ago [Jolivet et al. 2015, and references therein]. This migration has been interpreted as a consequence of a slab tear below the eastern Aegean and western Anatolia evidenced by seismic tomography [Biryol et al. 2011; de Boorder et al. 1998; Salaün et al. 2012]. The slab tear is thought to have occurred between 15 and 8 Ma by van Hinsbergen et al. [2005a, b] based on paleomagnetic data showing a fast clockwise rotation of continental Greece at that time [see also Kissel and Laj 1988 for the first evidence of this rotation].

3D numerical modelling indeed shows the migration of magmatism and rotations in the crust during the propagation of the tear [Sternai et al. 2014; Menant et al. 2016a, b].

The progresses of seismic studies led to the publication of maps of seismic anisotropy underneath the Aegean region [Hatzfeld et al. 2001; Endrun et al. 2008; Paul et al. 2014]. The comparison of these maps with the long-term extensional strain observed in the crust of the overriding plate [Jolivet et al. 2009; Kreemer et al. 2004] led to the idea that the asthenospheric flow produced by slab retreat was one of the main drivers of extension observed in MCC.

3-D numerical models have also shown that slab tearing and retreat are essential ingredients of the present kinematics observed in the Anatolian region. Elaborating on the original ideas that slab retreat and progressive narrowing by tearing concentrate the slab-pull forces controlling slab retreat and associated mantle flow, 3-D fully coupled thermo-mechanical models with original setups were tested on the eastern Mediterranean contexts [Capitanio 2014; Funiciello et al. 2003; Govers and Wortel 2005; Piromallo et al. 2006; Wortel et al. 2009]. These studies showed that the lateral evolution from continental collision in the east (Arabia–Eurasia collision) and subduction with slab retreat in the west (Hellenic subduction) lead to a rotational extrusion of the overriding continental lithosphere and that slab retreat is an essential component. Mapping the instantaneous strain field in the models [Sternai et al. 2014] shows the formation of a dextral shear zone similar to the North Anatolian Fault and an extensional domain similar to the Aegean. The modelled velocity field is very similar to that measured with GPS satellites [Le Pichon et al. 1995; McClusky et al. 2000; Reilinger et al. 1995, 2006].

The most recent part of the Mediterranean period is thus characterized by the progressive establishment of the current dynamics and the localisation of deformation along a few major structures, the North Anatolian Fault [Armijo et al. 1999; Le Pichon et al. 2003] and the Kephalonia Fault [Özbakır et al. 2020] as dextral strike-slip faults, active extension in the Corinth Rift [Armijo et al. 1996; Briole et al. 2000; Jackson et al. 1982; King et al. 1985; Lyon-Caen et al. 2004] and the Menderes Massif [Aktug et al. 2009; Gessner et al. 2001]. Active extension is also observed in the southern Aegean in the Amorgos graben and toward Santorini [Nomikou et al. 2018], in Crete and the Peloponnese [Armijo et al. 1999; Lyon-Caen et al. 1988]. This late localisation of deformation has left the Cyclades almost undeformed since the Late Miocene.

4. Tethyan period

The Tethyan period is characterized by the involvement of several basins belonging to the Tethyan realm (i.e. Maliac Ocean, Pindos Basin). These paleogeographic elements that appear in the Mid Triassic (rifting) were stacked during the Tertiary collision and were partly affected by the Jurassic obduction (Maliac). Later extension belongs to the Mediterranean period described above. For the Tethyan period, we have chosen to focus on the regions situated north of the Corinth Rift and more specifically to the north of the Sperchios. The characteristics of the main isopic zones (paleogeographic domains) are summarised on Figure 3.

4.1. Initial rifting (duration ca. 10 Ma)

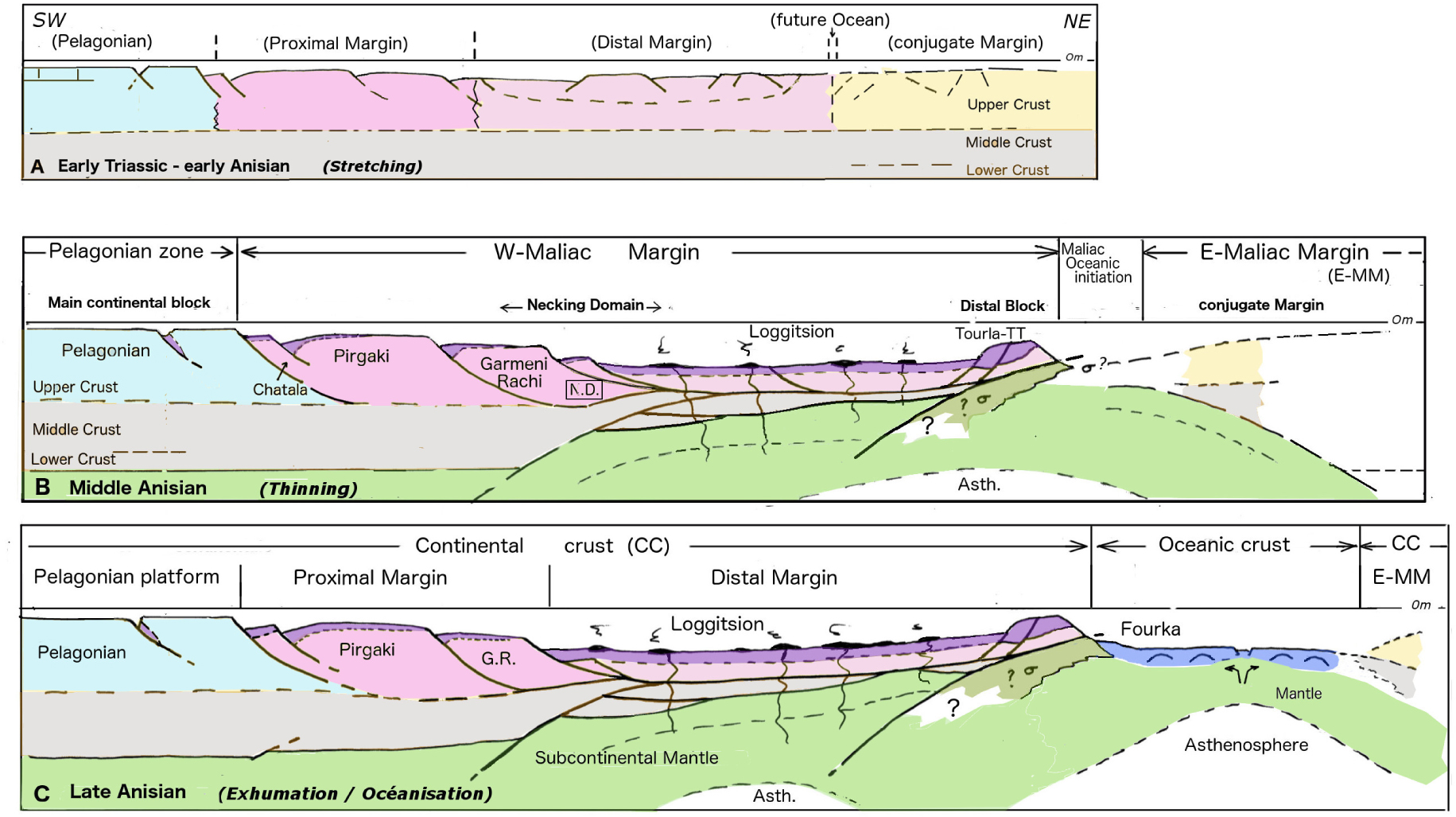

The Triassic rifting episode is recorded in a large portion of the Hellenic zones. One example of such a syn-rift evolution, the western margin of the Maliac Ocean, is proposed on Figure 7.

(A–C) The Rifting period. (A) Early Triassic to Early Anisian (stretching): platform limestones; (B) Middle Anisian (thinning): volcanism, pelagic facies on the proximal (and distal ?) margin; (C) Late Anisian: oldest Maliac oceanic crust; beginning of the post-rift period but the “syn-rift” volcanism reaches the Late Ladinian.

The pre-rift Mesozoic series, well known in the Internal Zones, are generally represented by a Lower Triassic-Anisian carbonate platform, resting on detrital metamorphic and non-metamorphic Palaeozoic formations. The rifting period is characterized in the Mid-Triassic by volcanism and changing facies in the Internal and Pindos Zones (Figure 3). This period lasts for approximately 10 Ma (ca. 247–237 Ma). In Othris, in the Maliac proximal margin, the Anisian benthic limestones are overlain by a syn-rift succession of calcareous breccias, radiolarites, black pelites and yellowish sandstones, associated with pillow-lavas and dolerites. In the distal Maliac margin, Late Ladinian and Carnian radiolarites directly overlain the lavas [Ferriere 1982].

Magmatism is well developed in the Pelagonian and the deep basins (Maliac Ocean and Pindos Zone). It is represented by basaltic pillow-lavas, dolerites and rare alkaline trachytes, like in Othris, or by porphyric andesites like in the Pindos or in Evia [Bortolotti et al. 2008; Celet et al. 1976a, b, 1980; Ferriere 1982; Lefevre et al. 1993; Monjoie et al. 2008; Pe-Piper 1998; Pe-Piper and Piper 2002]. In Othris, the upper part of the distal margin pillow-lavas is dated as late Ladinian by microfossils present in inter-pillow sediments [Ferriere 1982; Ferriere et al. 2015]. This volcanic formation is truncated at its bottom by a tectonic contact making an Anisian age possible for the initiation of the syn-rift volcanism, as demonstrated further north, in the Dinarides [Celet et al. 1976a, b; Sudar et al. 2013].

Two main geochemical trends are observed: (i) alkaline volcanism rich in pillow-lavas and basaltic flows evoking generalised extension. This is the case of the Triassic volcanism in Othris [Barth and Gluhak 2009; Bortolotti et al. 2008; Ferriere 1982; Hynes 1974] although more diversified affinities have been described with some supra-Subduction Zone (SSZ) lavas [Monjoie et al. 2008]; (ii) SSZ volcanism rich in basaltic lavas and andesites erupted in the context of active or extinct subductions with deep slabs inherited from the Paleotethys subduction. The consumption of the Paleotethys by these subduction zones would then be the cause of the opening of the Neotethys as a back-arc basin [van Hinsbergen et al. 2020; Maffione and van Hinsbergen 2018; Stampfli and Borel 2002]. An alternative interpretation excluding subduction and involving instead the partial melting of peculiar mantle compositions have been proposed [Pe-Piper 1998; Saccani et al. 2015]. Bonev et al. [2019] describe Triassic lavas of MORB and OIB type linked with the Volvi rift complex in the Serbo-Macedonian massif, then the margin of the Neotethys. Upper Mid-Triassic (U–Pb ages on zircon) metagranitoids have also been reported in association with the Cycladic Blueschists such as in Evia where they are possibly related to an anorogenic rift setting [Chatzaras et al. 2013]. Some older metagranitoids, Carboniferous in age (U–Pb on zircon) in the Cycladic Basement in Ios island have been attributed to subduction processes [Flansburg et al. 2019].

Syn-rift tectonic structures are almost unknown because of later deformation, early normal faults being reworked as syn-obduction nappe contacts during the Jurassic (Figures 7 and 8; and Section 4.3.3) [Ferriere et al. 2016; Ferriere and Chanier 2020, 2021].

(D–F) The post-Rift period: oceanic drifting (Maliac ocean): (D) Carnian: subsidence (thick black arrows), siliceous limestones and radiolarites (thick blackdashes) on the margin; (E) Early Jurassic: deep-sea fan with siliceous fine-grained limestones and calcarenites, calciturbidites (black triangles); (F) Middle Jurassic: convergence giving rise to the subduction–obduction processes. The Triassic syn-rift normal faults guide the Jurassic syn-obduction tectonic contacts.

The data summarised above indicate that the Triassic rifting creating the main paleogeographic domains corresponds to the Anisian and Ladinian periods. Syn-rift volcanism was locally active until the Late Ladinian and continued after the formation of the Maliac Oceanic crust (late Anisian) considered as the beginning of the Post-Rift period.

4.2. Oceanic spreading: the post-rift period (duration ∼ 70 Ma)

This period that sees the development of the main Hellenic paleogeographic domains, especially the Tethyan Maliac Ocean [Ferriere 1976b] lasted approximately 70 Ma, from 240 (Middle Triassic) to 170 Ma (Dogger pp) (Figure 8). Lavas of the ophiolitic units are dated from the Dogger in the Vourinos or Mega Isoma in Othris [Chiari et al. 2003; Ferriere et al. 2015; Liati et al. 2004]. On the other hand, the Fourka ophiolitic unit made of MORB-type pillow-lavas underlying the peridotitic units, is dated from the Triassic [Bortolotti et al. 2013], and locally more precisely from the Late Anisian with radiolarites in direct contact with the lavas [Ferriere et al. 2015], the oldest age for the Maliac oceanic crust.

The series deposited on the oceanic crust and on the margins record a thermal subsidence from the Middle Triassic to the Middle Jurassic. The margins of the main basins, notably the Maliac and Pindos Zones, are rich in calcarenites, sometimes turbiditic, with elements supplied by the bordering platforms where subsidence was compensated by an intense carbonate productivity. The distal margin of the Maliac Ocean, well characterized in Othris, is rich in lavas, radiolarites and pelites, making these units difficult to distinguish from the Middle Jurassic of the syn-obduction underlying units [Ferriere 1974, 1982]. The most distal formations are rich in Early Jurassic siliceous pelites, but, as in the entire Hellenides, the absence of Liassic determinable radiolarian does not permit to date precisely this period [cf. Chiari et al. 2013]. The transition from the post-rift divergence to the first convergence (Dogger subduction and obduction) is marked by a fast subsidence in some of the Internal Zones (Figure 8F).

4.3. Early convergence: Jurassic subduction(s) and obduction(s)

4.3.1. The Hellenic ophiolites

Obduction characteristics are nicely illustrated in the Hellenides, whether for the petrology of ophiolites (e.g., Vourinos and N-Pindos) or the syn-obduction tectonic units originated from the Maliac Ocean and its margins in Argolid and Othris. Recent synthetic publications develop various hypotheses for this obduction event. Most geologists consider that the concerned ocean was located on the eastern side of the Pelagonian continental domain [e.g. Bortolotti et al. 2013; Ferriere and Chanier 2020; Schmid et al. 2020; Ferriere et al. 2012, 2015, 2016, therein references].

Three main ophiolitic nappes coming from the Maliac Ocean are present in the Pelagonian domain [e.g., Brunn 1956; Ferriere et al. 2012]. Two thick nappes with complete succession from peridotites to lavas: the Mega Isoma Unit in W-Othris and the N-Pindos Unit (N-Hellenides) mainly with MORB lavas and the more eastern Metalleion Unit in W-Othris and the Vourinos Unit (N-Hellenides) with SSZ lavas [e.g., Brunn 1956; Beccaluva et al. 1984; Ferriere 1982]. The lavas of the Vourinos and Mega Isoma nappes are dated by radiolarian as Late Bajocian and Bathonian [Chiari et al. 2003; Ferriere et al. 2015]. The third supra-Pelagonian ophiolitic nappe [Fourka unit, Celet et al. 1980], located just below the main ones is very different. It consists of pillow-lavas of MORB affinities dated as Middle Triassic [Bortolotti et al. 2008], locally Late Anisian immediately above the lavas [Ferriere et al. 2015].

In the Internal Zones, the Guevgueli ophiolites are considered as back-arc ophiolites on the eastern side of the Jurassic Paikon volcanic arc [Bebien 1983; Ferriere and Stais 1995; Mercier 1968; Mercier et al. 1975; Saccani et al. 2008]. The origin of the Rhodope ophiolites is discussed [Froitzheim et al. 2014].

4.3.2. The first evidence of convergence: Jurassic subduction(s)

Magmatic witnesses are the main arguments concerning the existence of one or two Jurassic subduction(s) in the Maliac Ocean: (i) In the supra-Pelagonian Vourinos ophiolites, the characteristics of the peridotites, mainly harzburgites and of the overlying Middle-Jurassic lavas indicate a supra-Subduction Zone (SSZ) environment [Beccaluva et al. 1984]. Boninitic dykes and SSZ-type lavas are also reported above MORB-type lavas from the N-Pindos ophiolites [Saccani and Photiades 2004; Saccani et al. 2004] (Figure 9). Evidence of subduction extends in Albania where one can distinguish the same framework with a western unit rich in MORB lavas and an eastern one with SSZ andesites and rhyolites [Dilek et al. 2008; Dilek and Furnes 2009]; (ii) The interpretation of the Paikon as a volcanic arc associated with the Guevgueli back-arc basin is also a convincing argument for the existence of a Jurassic subduction on the Maliac eastern margin [Bortolotti et al. 2013; Danelian et al. 1996; Ferriere and Stais 1995; Ferriere et al. 2012, 2015, 2016; Kukoc et al. 2015; Mercier et al. 1975; Robertson 2012; Saccani et al. 2008].

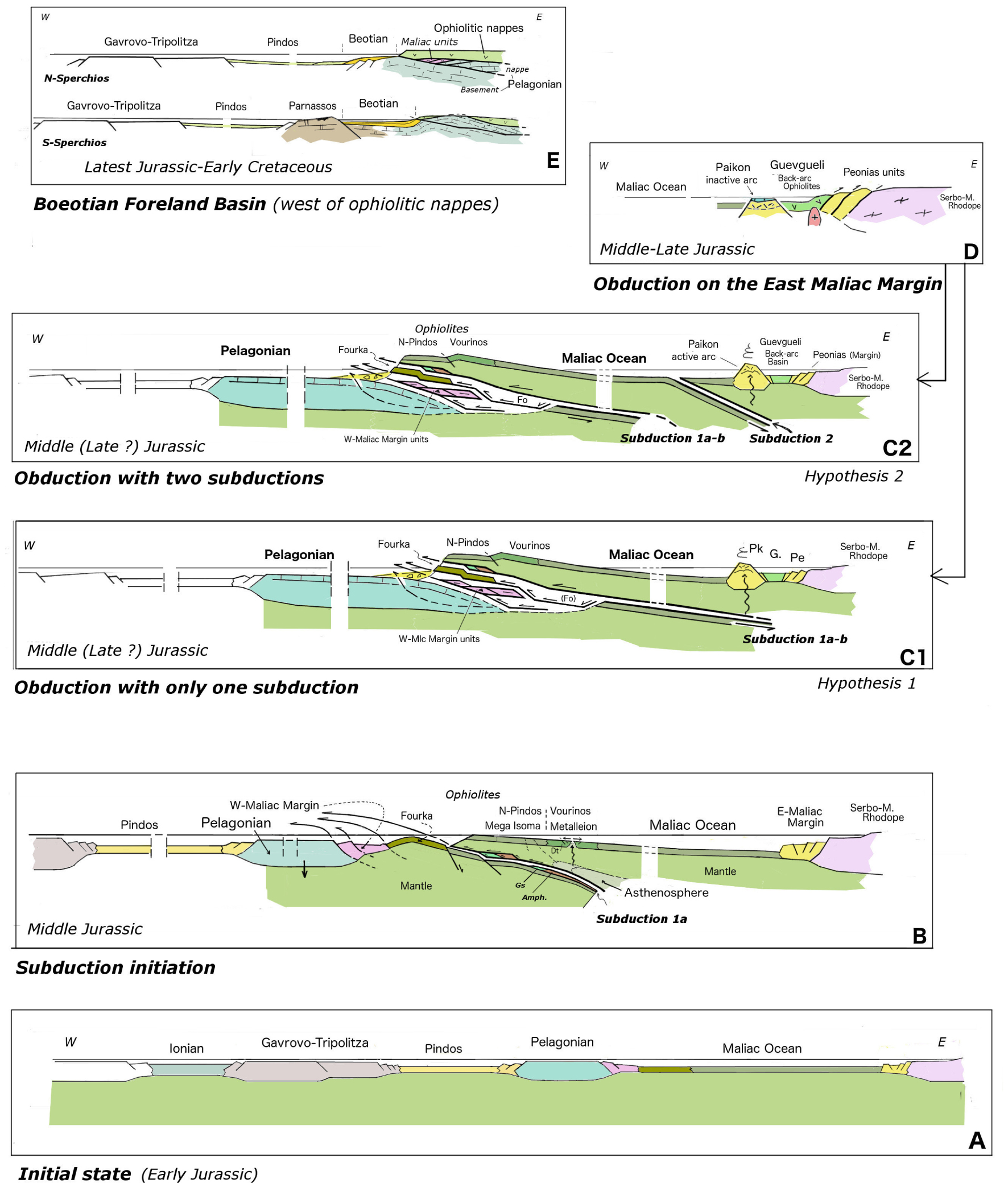

Jurassic Obduction. (A–E) The obduction process and its consequences (Beotian Basin). (A) Initial state; (B,C) west-verging Maliac obduction toward the Pelagonian domain; (C1,C2) two hypotheses concerning the subduction(s), (C1) the supra-Pelagonian SSZ ophiolites (Vourinos, Metalleion) and the Paikon arc to the east, are linked to the same subduction; (C2) two different subductions are responsible for the western SSZ ophiolites and for the Paikon arc and Guevgueli back-arc basin; (D) East Maliac obduction toward the East; (E) Foreland Boeotian sedimentary domain.

Metamorphic data also document the subduction and obduction history in the Hellenides.

High-temperature amphibolite-facies units resting on top of lower temperature (greenschist-facies) lenses are present below the ophiolitic nappes in the Hellenides Brunn [1956], Spray et al. [1984]. In the Albanides, the thick metamorphic sole associated with the Mirdita ophiolites gave thermobarometric constraints: 800–860 °C and 1 GPa [Dimo-Lahitte et al. 2001], but the main amphibolite units show temperatures ranges from 624 ± 9° to 796 ± 50 °C with pressures always lower than 0.7 GPa [Gaggero et al. 2009] (Figure 9B). These metamorphic soles, made of metabasites and pelagic sediments are classically interpreted as metamorphosed and deformed at the onset of the subduction and dragged at the base of the ophiolitic nappes while obduction advances [Agard et al. 2016, 2020; Plunder et al. 2016].

Taking into account the location of the Tethyan Maliac Ocean on the eastern side of the Pelagonian block, an eastward dipping intra-oceanic subduction has to be considered to explain the emplacement to the west of the Jurassic supra-Pelagonian ophiolites.

Two possibilities arise for the number of subductions: In the first hypothesis (Figure 9, C1) the subduction below the Maliac eastern margin with the Paikon arc is also responsible for the development of the Vourinos SSZ Unit, and partly of the N-Pindos one. The Bathonian ages of some radiolarites deposited on lavas of the Guevgueli back-arc basin [Kukoc et al. 2015] similar or close to the Middle Jurassic ages of the Vourinos SSZ lavas (Figure 3) are not opposed to such a single subduction in the Maliac ocean. In the second hypothesis, more likely (Figure 9, C2), a second subduction zone, further west, would be responsible for the Vourinos SSZ oceanic lithosphere. The subduction under the Paikon arc would be due to blocking during the obduction of the ophiolites onto the Pelagonian continental domain. In the Hellenides, the similarities of the obduction history from Greece to former Yugoslavia imply localisation within a zone that ran parallel to the earlier paleogeographic domains. The Mid-Jurassic ages of the MORB-type ophiolitic lavas of the N-Pindos and those of the Mega Isoma lavas (Othris), very close to the age of the obduction events, indicate that they were formed near the active Maliac Mid-Oceanic ridge (Figure 9), thus far from the active eastern margin of the 70 Ma old Triassic–Jurassic Maliac ocean. Maffione [2015] and van Hinsbergen et al. [2015] partly based on numerical modelling, propose an initiation of subduction near the mid-ocean ridge by the reactivation of a detachment fault similar to those observed in slow accretion contexts. Assuming the existence of such an east-dipping detachment, on the western side of the Maliac ridge, this hypothesis allows the evolution of the former ridge in a forearc domain with a thin lithosphere and its magmatic consequences. The origin of the Middle Jurassic Vourinos lithosphere could be the result of such a geodynamic context. The more western N-Pindos ophiolites corresponding to a MORB-type oceanic crust would have been trapped in the upper plate of the subduction zone, then covered or crossed by SSZ pillow-lavas and dykes [e.g., Saccani and Photiades 2004].

By contrast with the main peridotitic ophiolite units, the Triassic Fourka oceanic unit, located near the continental-oceanic transition (between Pelagonian distal margin and the early Maliac oceanic crust), was part of the lower plate of the intra-oceanic subduction before the continental subduction of the Pelagonian domain (see infra Section 4.3.3).

4.3.3. Development of obduction on the West-Maliac continental margin

The evolution from a young intra-oceanic subduction to obduction corresponds to the overthrusting of the oceanic lithosphere on the continental crust that starts to subduct; the case of the Hellenides is rich in examples of this process [Bortolotti et al. 2013; Ferriere 1985; Ferriere et al. 2012, 2015, 2016; Papanikolaou 2009; Rassios and Moores 2006; Robertson 2012; Saccani et al. 2011; Smith and Rassios 2003].

The first signs of convergence are characterized by a massive subsidence of the Pelagonian continental domain and its margin. Radiolarites are deposited on the different domains, including the benthic limestones of the Pelagonian Zone (Figure 10D). The Tourla-Trilofon (TT) Unit, locally showing Triassic benthic limestone blocks, makes the transition between the Maliac distal margin and the ophiolitic nappes (Figures 7 and 10).

Caption continued on next page. Jurassic Obduction. This figure exposes: (i) the thrusting of the Triassic Fourka ophiolitic unit located on the lower plate (A–D) and, (ii) the obduction development taking into account the different ophiolitic mélanges (D–G). (A) Pre-convergence initial state; (B) Mid-Jurassic intra-oceanic Subduction development; (C) Obduction upon the distal margin of the Fourka unit (oceanic pillow-lavas unit) located on the oceanic lower Plate; (D) obduction of the main peridotitic ophiolitic nappes coming from the oceanic upper Plate and fast underthrusting of the thin continental crust distal margin (ca. no mélanges); (E,F) development of mélanges in areas with thick continental crust (Proximal margin and Pelagonian zone; low underthrusting) in front of the upper syn-obduction nappes (ophiolitic and distal margin units); (G) Boeotian foreland basin development.

This intensely deformed TT Unit is the first domain of the margin overthrust by the ophiolitic nappes, in this case the Triassic Fourka ophiolites [Ferriere 1982]. The expected fate of such an oceanic lithosphere of the Continent–Ocean Transition, furthermore, belonging to the oceanic lithosphere of the downgoing plate of the oceanic subduction zone, is that it underthrusts the continental lithosphere, while the opposite is observed here (Figures 9 and 10).

Two additional processes accompany the overthrusting of the Fourka unit (Figure 10C): (i) the subsidence of the continental margin, attested by the deposition of radiolarites on top of all the margin series; (ii) the progression of the thick intra-oceanic nappes of peridotites inducing a tilting of the oceanic crust of the Fourka Unit and then a decollement of its upper part allowed by the presence of serpentinites.

The nature and distribution of mélanges at the front of the syn-obduction Maliac units provide insights on the emplacement of these nappes in Greece or in Albania [Celet et al. 1977; Ferriere 1982; Ferriere and Chanier 2020; Gawlick et al. 2008] (Figure 10D–F). For instance, in Othris, the thin distal margin crust soon underthrusts the ophiolites, preventing the massive formation of syn-obduction mélanges on the top of these units, while mélanges are widely observed on the proximal margin units because of their thicker crust, the underthrusting of which creates relief and erosion during a long period. The Pelagonian platform behaves the same way with mélanges fed by the ophiolites and distal margin units while the proximal Maliac margin units are overrun and dragged under the overriding nappes (Figure 10F).

Possible inheritance of early faults exists in syn-obduction nappes. The reconstitution of the West-Maliac margin shows fast sedimentation jumps between units supposedly close to each other on the margin. We have attributed these fast changes to normal faults, within the margin [Ferriere 1982; Ferriere and Chanier 2020]. The reactivation of such faults, mostly dipping oceanward, have facilitated the formation of nappes from the margin. During the progression of these nappes, a decollement localized within or underneath the Middle Triassic syn-rift lavas (distal margin) or deeper in the series, mainly the base of the Early Triassic Ansian limestones (proximal margin). In Othris, in the proximal margin units, tectonic structures are organised with pluri-kilometric fault-bend folds overturned toward the west. Cretaceous deposits, locally unconformable on one of these syn-obduction major structures, support the hypothesis of a Maliac Ocean east of the Pelagonian [Ferriere 1982].

Concerning syn-obduction metamorphism, different cases have to be distinguished. The metamorphic transformations observed within the ophiolites are linked to their evolution within the ocean. The case of the metamorphic soles with amphibolites and greenschists was discussed above (Section 4.3.1). In the Hellenides, in Argolid and Othris, syn-obduction sedimentary units do not show any metamorphic overprint of that age. In other sectors, further east or northeast [e.g., Pelion, Ferriere 1976b, 1982], Tertiary metamorphisms mask possible earlier metamorphic events. In a few sectors, however, Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous metamorphic ages have been obtained in the basement [Kilias et al. 2010; Most 2003; Mposkos et al. 2010]. For instance, Kilias et al. [2010] describe within the Pelagonian basement in the northern Hellenides, a succession of tectonic events with local evidence of HP-LT metamorphism attributed to the obduction at 160–150 Ma, locally preserved in a greenschist to amphibolite-facies event at 150–130 Ma. Anyhow, such syn-obduction HP-LT metamorphic events coeval with Jurassic obduction seem to be rare in the Hellenides.

Some sediments allow us to precise the duration of the obduction processes in Argolid [Baumgartner 1985; Ferriere et al. 2016]. There, spinels reworked in sediments deposited at the Callovian–Oxfordian limit (ca. 163 Ma) on the West Maliac margin, are the first witnesses of the proximity of the ophiolitic nappe. The ages of the syn-obduction mélanges and clastic formations deposited on the Pelagonian domain are latest Oxfordian p.p.–Kimmeridgian (ca. 158–154 Ma) and Late Kimmeridgien–Early Tithonian (ca. 153–150 Ma). The Tithonian deposits rest unconformably on the syn-obduction units, implying a duration of the order of 10 Ma.

4.3.4. Obduction on the East-Maliac margin

Another obduction event recorded on the East-Maliac margin is temporally close to the west-Maliac ophiolites emplacement (Middle Late Jurassic). As described above, the East-Maliac margin is associated with a back-arc basin with a Middle–Upper Jurassic oceanic crust (Guevgueli domain) between the Paikon and Peonias Units in the west and east, respectively (Figure 9). When restoring the situation before the Cenozoic deformations, one observes that the back-arc ophiolites were overthrusted on top of the Peonias margin units, i.e., eastward, a situation opposite to that of the supra-Pelagonian ophiolites [Ferriere and Stais 1995; Ferriere et al. 2012, 2016]. Obduction on the East-Maliac margin dates back to the Jurassic as shown by the Bathonian to Oxfordian ages of deformed radiolarites deposited on the Guevgueli ophiolitic lavas (cf. Section 4.3.1) and the Tithonian age of unconformable conglomerates [Mercier 1968]. A set of granites and migmatites dated around 150 Ma intruded the ophiolitic complex [Mercier 1968], confirming this conclusion.

4.4. The post-obduction and pre-collision period: the Latest Jurassic and Cretaceous

Well-dated series spanning the Upper Jurassic and the Early Cretaceous are locally observed on the ophiolites in Theopetra, close to Meteora, [Ferriere 1982; Surmont et al. 1991] or further north, in the Vourinos area [Mavridis et al. 1993; Fazzuoli and Carras 2007]. Unfortunately, these series are not observed resting on the thrust contacts between the ophiolites and the Pelagonian substratum, the question is whether these layers, or part of them, were deposited during or after the obduction. The end of the obduction period is characterized by a large reworking of the paleogeography of the Internal Zones and their external rim where the Beotian basin developed (Figures 9 and 10) as a flexural foreland basin in the front of the obduction chain, hosting a flysch rich in ophiolitic elements as soon as the Tithonian [Celet et al. 1976a, b]. South of Sperchios (Figure 1), this important Beotian basin develops on top of a single large platform domain, at the boundary between the Pelagonian platform covered with ophiolitic nappes in the east and the Parnassus platform in the west, untouched by the obduction (Figures 1, 9 and 10).

Several Cretaceous reconstructions show a remnant post-obduction ocean in the Almopias area, between Paikon and Pelagonian, sometimes named “Vardar Ocean” [van Hinsbergen et al. 2020; Menant et al. 2016a, b; Stampfli and Borel 2002]. In this Almopias sector, along the western border of the Paikon, the Kranies–Mavrolakkos series, made of MORB pillow-lavas and rare depleted lavas covered with Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous radiolarites and a flysch-type detrital formation (Figure 3, kr) could testify for a deep oceanic environment [Bechon 1981; Ferriere and Stais 1995; Mercier 1968; Saccani et al. 2015; Sharp and Robertson 2006; Stais et al. 1990].

Two interpretations can be envisaged: either the remains of the eastern part of the Maliac oceanic crust obducted toward the west during the Middle-Late Jurassic, or the neoformation of an oceanic basin during the late stages of obduction or just after. The imprecise age of the radiolarites renders the choice between these two hypotheses difficult.

The period that can undoubtedly be considered as post-obduction, starts in the Barremian–Aptian (ca. 125 Ma). Due to the Albian–Turonian eustatic transgression, marine formations develop on the already emerged Internal Zones. Calcareous fine-grained formations are deposited in the deep regions such as the Pindos and the Beotian basins (Figure 3). A mid-Cretaceous formation called “premier flysch du Pinde” [Aubouin 1959; Fleury 1980] testifies for vertical movements along the rims of that basin. Chaotic formations in the Almopias domain have been attributed to Early Cretaceous strike-slip movements [Vergely 1984; Mercier and Vergely 1972]. According to Schenker et al. [2014], an Early Cretaceous blueschist facies event in the Pelagonian was followed by an amphibolite-facies overprint (116 ± 8 Ma). Lips et al. [1998] proposed HP-LT metamorphic ages ranging from 100–85 Ma to about 54 Ma in the Pelagonian of the Ossa Massif, thus characterizing an “early–middle Alpine cycle”. Cretaceous ages were also obtained in the Cycladic Blueschists [Altherr et al. 1994; Bröcker et al. 2014]. Foliated amphibolites interpreted as the sole of an ophiolitic nappe were dated from the Late Cretaceous (70–75 Ma) in Syros [Maluski et al. 1987] or Tinos [Patzak et al. 1994; Searle and Lamont 2022]. A Late Cretaceous obduction is widely recognised along the Izmir–Ankara suture zone further east [Okay and Tuysuz 1999]. A first-order question then arises about the relationships between the Late Jurassic obduction on the Pelagonian zone and the Late Cretaceous obduction observed in the Cyclades and further east. Finally, at the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary, the deposition of the flysch deposits in the Internal Zones is the first evidence of the Hellenic collision (Figure 3) [Aubouin 1959].

4.5. Tertiary Collision

The notion of collision is partly debatable. Does it correspond to the moment when the last oceanic space has been consumed by subduction or to the period of strong mechanical coupling between the two continental crusts and consequential shortening of the downgoing one? In the Alps, a clear distinction is usually made between the two periods, the first one being described as a continental subduction and the second one, after 32 Ma, as real collision [Bellahsen et al. 2014].

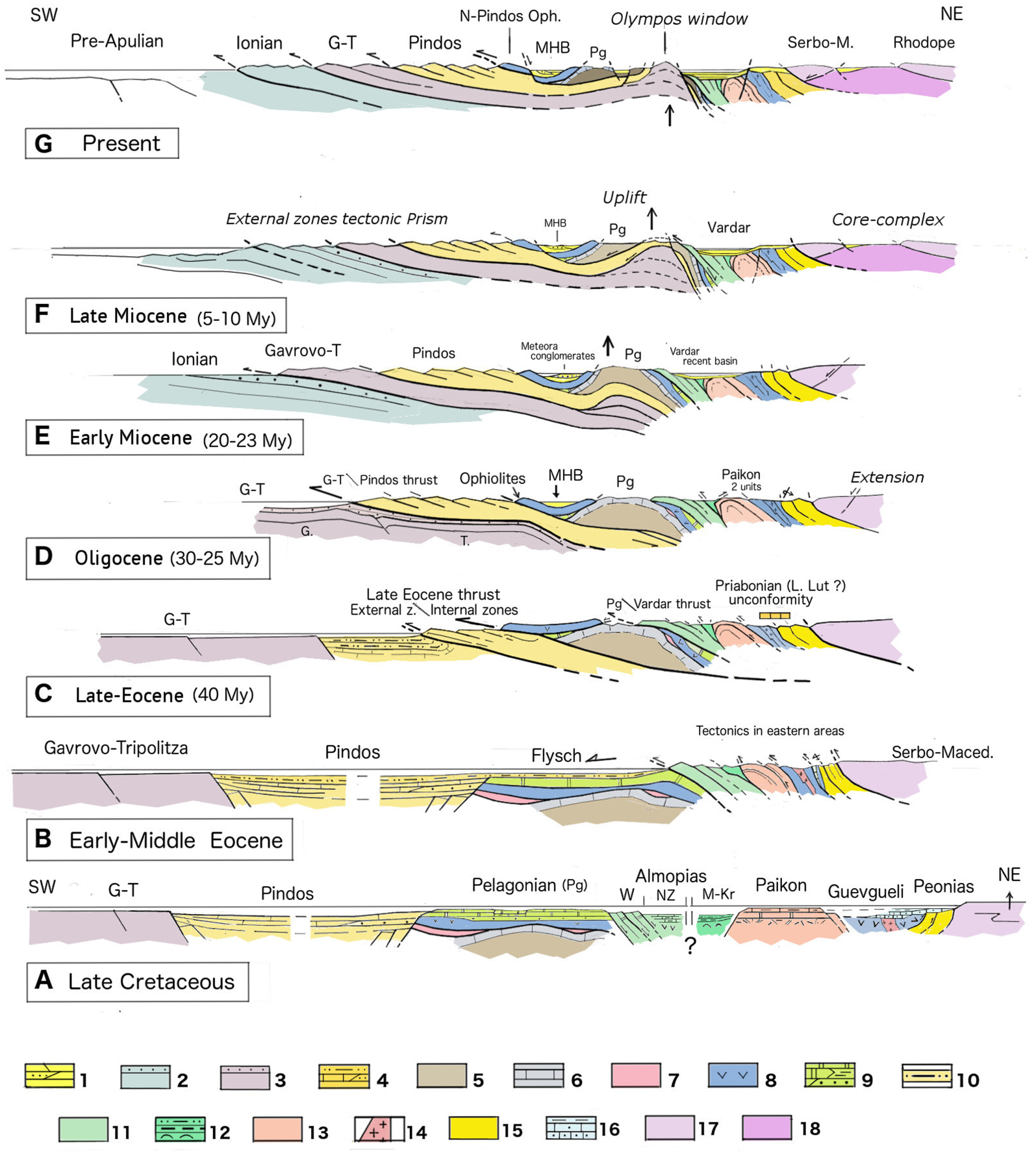

In the Hellenides, the disappearance of the last Tethyan oceanic space between Apulia (Adria) and Eurasia (Rhodope s.l.) is dated to 70–65 Ma [Menant et al. 2016a, b], even to 40–35 Ma considering the Pindos zone uncertainty (Figures 1 and 11).

Tertiary Collision; example of the northern Hellenides. (1) Recent sedimentary basins (Oligocene to present); (2) Ionian units (U.) on the western Adria continental block; (3) Gavrovo-Tripolitza platform and U.; (4) Pindos basin and U.; (5,6) Pelagonian basement (5) and Triassic–Jurassic limestones (6); (7) Maliac margin U.; (8) ophiolites; (9) unconformable Cretaceous cover (Pelagonian); (10) flyschs; (11) western (W) and central (C) Almopias U.; (12) eastern Almopias U. (M: Mavrolakkos; Kr: Kranies); (13) Paikon U.; (14) granits through Guevgueli ophiolites; (15) Peonias U.; (16) unconformable Tithonian–Lower Cretaceous sedimentary cover above the Peonias-Guevgueli U.; (17,18) Serbo-Macedonian and Rhodopian upper (17) and lower (18) units. (A) Late Cretaceous state with several deep basins (Peonias-Guevgueli, Almopias, Pindos and Ionian basin on a more eastern area) between elevated domains; (B) beginning of the Eocene compressive deformation in the eastern domain (Collision s.l.); (C) Late Eocene: beginning of the underthrusting of the Pindos zone below the Internal Zone; the compressive tectonic goes on in the eastern Internal Zones (from Paikon area with two superposed units); (D) Oligocene: underthrusting of the Gavrovo-Tripolitza domain and Extensional deformation in the Serbo-Macedonian–Rhodopian domain; (E,F) Early to Late Miocene: deformation of the Ionian and more external zones and Olympos-Ossa uplift (black arrow); (G) Pliocene-Quaternary extensional deformation in the eastern Hellenides and compressive deformation in the western Hellenides.

4.5.1. Sedimentary markers of collision

In the Hellenides, collision, or continental subduction, is characterized by the deposition of thick flysch series invading the Internal Zones and the Pindos Basin, as soon as the Maastrichtian or Paleocene. The space–time evolution of the ages of these flysch formations, more recent westward (Figure 3), illustrates the idea of “orogenic wave” [Aubouin 1959]. The source, of the sediments, sometimes attributed to islands in the Pelagonian domain is more likely to be found further east, notably in the Serbo-Macedonian-Rhodope block, as the Almopias series are also onlapped by a flysch as soon as the Maastrichtian pp [Mercier 1968; Sharp and Robertson 2006].

The age and localisation of the piggy-back Mesohellenic Molassic Basin (MHB) (Figures 2B and 3) have recorded some of the tectonic events affecting the Hellenides from the Late Eocene to the Middle Miocene (ca. 40 Ma to 15–10 Ma) (Figure 2B) [Brunn 1956; Doutsos et al. 1994; Ferriere et al. 1998, 2004, 2013; Vamvaka et al. 2006; Zelilidis et al. 2002].

In the Late Eocene, the subduction of the Pindos basin led to the formation of limited basins in the upper unit of the Internal Zones, as the deep flysch basin of Krania. From the Oligocene, the subduction of the Gavrovo-Tripolitza platform determines the development of the real MHB of 300 km × 30 to 40 km, striking NW–SE, which rests unconformably on the late Eocene basins but also on the “Frontal Thrust of the Internal Zones” developed on the External Zones [Ferriere et al. 2004, 2013]. Further east, the extension controlling the formation of the Rhodope MCC may also have started during the Late Eocene [Brun and Sokoutis 2007; Sokoutis and Brun 2018] (Figure 11), but alternative interpretations make compressional tectonics last until the Early Oligocene, at about 33 Ma [Gautier et al. 2010, 2017].

Close to the Oligocene–Miocene boundary, a new major event is attested by the thick sandstones and conglomerates deposited in shallow marine environments (Meteora Gilbert-type deltas) [Brunn 1956; Ori and Roveri 1987; Ferriere et al. 2011]. The detrital elements are linked to the uplift of the eastern Pelagonian sector of the MHB probably due to the development of ramps and duplexes within the underthrust Gavrovo-Tripolitza Zone, which also explains the eastward propagation of depocenters starting at the end of the Oligocene. Thermochronological studies (apatite and zircon fission-tracks) provide some more precision of the timing of the exhumation of the Pelagonian domain [Schenker et al. 2015]. A fast exhumation in the Eocene and slower exhumation in the Oligocene and Miocene have been proposed [Vamvaka et al. 2010]. Along a transect running from the Pelagonian to Mt Olympos, fast exhumational cooling occurred between 12 and 8 Ma at rates of 15–35 °C/Ma and decreased to <3 °C/Ma by 8–6 Ma [Coutand et al. 2014]. Numerous normal faults exist until the recent Plio-Quaternary extension.

Once sedimentation stopped in the MHB, near the Miocene–Pliocene boundary, a new basin developed further east with the same Hellenic strike, the Larissa-Ptolemais Basin. This process leads to the morphology in continental Greece, characterized in the Internal Zones by a succession of ridges and basins, with a wavelength of ∼30 km (Figure 2B).

4.5.2. Tectonic structures and metamorphic events related to the Tertiary collision

The structures related to collision are easy to recognise in the Hellenides External Zones as they have not been affected by the Jurassic obduction: a Tertiary “fold-and-thrust belt” developed, associated with the formation of major nappes. The NW–SE striking structures are SW verging [Aubouin 1959; Doutsos et al. 1993, 2006; van Hinsbergen et al. 2005a, b; Skourlis and Doutsos 2003]. NE-dipping previous syn-rift normal faults (i.e., SW margin of Pindos Basin) were inverted to form major thrusts, while on the opposite where the normal faults dip to the SW (i.e., NE Pindos margin), tectonic units are verticalized (i.e. Koziakas and Vardoussia units, Figure 1). Compared to northern Hellenides, the large-scale structure seems more complex in the Peloponnese where major tectonic windows are recognised in the Taygetos and Parnon (Figure 1) showing external units including the Ionian series (Palttenkalk), underneath the Pindos and Gavrovo nappes [Doutsos et al. 2006; Jolivet et al. 1996, 2010a, b; Thiébault 1982]. The importance of the shortening is attested by these tectonic windows in the Peloponnese but also in the northern Hellenides where such windows (e.g., the Olympos window) are known in the Internal Zones (Figure 1).

Two Tertiary belts of HP-LT metamorphism are observed: In the north-eastern Hellenides, Eocene blueschists are found in the Olympos-Ossa and Almyropotamos tectonic windows below the Pelagonian units [e.g., Godfriaux 1968; Katsikatsos et al. 1976; Schmid et al. 2020; Xypolias et al. 2012] (Figure 1).

The Ambelakia unit, attributed to the Pindos zone, shows blueschist-facies parageneses. The underlying Gavrovo-Tripolitza (GT) unit locally shows HP-LT parageneses with the occurrence of lawsonite in the Eocene flysch topping this unit and relict glaucophane and phengite in some layers [Shaked et al. 2000]. These tectonic windows are also observed in the Cyclades where they are reworked by the Oligo-Miocene extension. The Cycladic Blueschists are lateral equivalents of the Ambelakia unit, part of the Pindos Basin [Bonneau 1984; Jolivet et al. 2004a, b; Hinshaw et al. 2023]. The underlying so-called Basal Unit observed on Tinos or Samos is similar to the Gavrovo-Tripolitza [Jolivet et al. 2004a, b; Ring et al. 1999]. Two compatible solutions can be proposed for the uplift of the Olympos window: (i) the uplift of the shoulder of the Thermaikos Gulf rift is controlled by the large normal faults bounding the Olympos massif to the east [e.g., Schmid et al. 2020]; (ii) the uplift is due to the backthrusting of the GT series against a ramp corresponding to the Pelagonian/Vardar boundary (Figure 11) [Ferriere et al. 2004, 2013]. The confirmation by zircon and apatite fission-tracks [Vamvaka et al. 2010; Coutand et al. 2014] of the west-to-east migration of uplifts within the Pelagonian domain is in favour of this second mechanism, but in any case, the uplift was exacerbated during the recent extension.

The second HP-LT belt observed in the Peloponnese tectonic windows (Figures 1 and 4), in Kythira and in Crete [Bonneau 1973; Creutzburg 1977; Greilling 1982] is more recent with peak-pressure ages ranging from the Oligocene to the Early Miocene [Brix et al. 2002; Jolivet et al. 1996, 2010b; Seidel 1978; Seidel et al. 1982; Ring et al. 2001; Theye and Seidel 1991; Theye et al. 1992; Thomson et al. 1998]. There, the external Phyllite–Quartzite Nappe (PQ) and the underlying Plattenkalk (PK) Nappe (or Ionian Nappe) show HP-LT parageneses characterized by the occurrence of Fe–Mg carpholite, lawsonite ± chloritoid and garnet in the metapelites. Fe–Mg carpholite is also observed in metabauxites found in the Plattenkalk, as well as aragonite in the marbles [Jolivet et al. 1996, 2010a, b; Seidel et al. 1982; Theye and Seidel 1991; Theye et al. 1992]. The PQ nappe, which shows considerable thickness variations, probably resulting from large-scale boudinage [Jolivet et al. 1996, 2010a, b] is made of a sequence of metapelites of Triassic age, with also conglomerates, quartzites and limestones, as well as slices of Paleozoic basement in Kythira and Crete [Romano et al. 2004; Seidel et al. 2007]. Because of these ages, the PQ nappe has often been confused with the overlying Tyros Beds, the lowermost part of the GT stratigraphy, in the Zaroukla–Feneos window, for instance [see a discussion in Jolivet et al. 2010b]. However, as the GT Nappe does not show any HP-LT overprint, a clear metamorphic gap is observed between the PQ Nappe and the overlying Tyros beds. The low-angle contact between this unmetamorphosed GT nappe and the metamorphic units underneath is a former thrust reactivated as a major detachment, the Cretan Detachment [Fassoulas et al. 2004; Grasemann et al. 2019; Jolivet et al. 1994a, b, 1996, 2010b].

The presence of HP-LT parageneses in the PQ and PK Nappes shows that they have been subducted to large depth during the Oligocene and the Early Miocene, which corresponds to the collision and shortening of the External Zones in the Hellenides.

The subduction and exhumation of these continental units were also coeval with the extension developing in the back-arc region and the exhumation of hot and cold metamorphic core complexes [Jolivet et al. 1994a, b, 2010b]. These metamorphic external units (PQ and PK) do not crop out north of the Corinth Rift. They probably continue at depth below the Parnassus, Pindos and GT nappes of the External Hellenides, but the deep geometry there is unknown. Their exhumation in the Peloponnese and Crete results from the kinematics imposed by slab retreat and the P–T conditions are in part dictated by the velocity of that retreat, with colder conditions in Crete than in the Peloponnese [Jolivet et al. 2010b]. If the amount of shortening is about 300 km by the addition of the horizontal displacements of the Pindos and GT nappes present in the Olympos window, in the Peloponnese, as the significance of the Phyllite–Quartzite (PQ) Nappe remains to be ascertained, the amount of shortening cannot be specified.

Structures observed in the Internal Zones, already deformed during the Jurassic obduction, are different from those of the External Zones.

East of the Vardar, Peonias units overthrusting toward the east in the Late Jurassic obduction, are overturned toward the SW, locally leading to inverted series (Figures 2A and 11) [Ferriere and Stais 1995]. Further west, in the Paikon domain, several interpretations of the Tertiary structures were proposed: (i) the Paikon is a single unit between two west-verging thrusts [Mercier 1968] or two thrusts with opposite vergence [Brown and Robertson 2003; Vergely and Mercier 2000]; (ii) one or two windows may exist, either a window opened on Pelagonian units [Godfriaux and Ricou 1991; Katrivanos and Kilias 2013; Ricou and Godfriaux 1995], or a window opened on Paikon type-series, below a nappe consisting of the upper part of the same Paikon type-series [Ferriere et al. 2001]. Finally, in the Almopias area, the previous Maliac Tethys oceanic suture, numerous thrust units with SW vergence have developed, the lowermost of which overthrust the Pelagonian domain [Mercier and Vergely 1984] (Figure 2A).