1. Introduction

Estuaries and coastal settings are environments at the interface between the emerged lands and the marine domain; they are known to be very reactive milieus. In fact, they collect everything that rivers transport in particulate, colloidal or dissolved form, they accumulate this material temporarily and redistribute it, in a more or less sequential way, towards the marine environment (e.g., D. Burdige, 2011, and reference therein). In particular, these phenomena are crucial for iron, which is an essential element for marine biodiversity, starting with microbial populations (Canfield, 2006; Laufer et al., 2016; Adhikari et al., 2017). Such proximal deposits are often rich in organic matter, both of autochthonous marine origin and of allochthonous terrestrial origin, and this organic matter can support intense microbial activity, which in turn impacts a significant number of early diagenetic reactions and growth of authigenic minerals (B. B. Jørgensen, 2006; Bianchi et al., 2016; Arellano et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2024). Woody debris, known to be refractory, that is, difficult to degrade, are most often the only organic remains observed in ancient coastal sediments, typically sandy deposits, indurated or not (e.g., Tyson, 1995). In these sands and sandstones, the more labile organic matter has most often been entirely remineralized via bacterial reactions capable of generating or inducing the formation of authigenic minerals, typically pyrite (B. B. Jørgensen et al., 2019, and references therein).

We are interested here in the reactions occurring during the early diagenesis of sandy deposits, and in the authigenic minerals that result from them. Sands and sandstones are often porous and permeable media (at least during part of their diagenetic curse) and fluid circulations often induce the dissolution of chemically fragile minerals, so much so that the sandstones of shoreface environments only contain very poorly soluble minerals (usually, quartz and heavy minerals). The memory of these fleeting authigenic minerals can nevertheless be preserved if early cementation can seal the porosity, thus preventing the fragile minerals from dissolution. From this perspective, we study here sandy deposits that underwent selectively located, early cementing, and we compare the mineralogical composition of uncemented sands and that of their contemporary equivalents, cemented early. The sediments studied belong to the geological formation of Grès de Châtillon (Kimmeridgian) cropping out along the cliffs of Boulonnais (northernmost France, Strait of Pas-de-Calais; Figure 1; Geyssant et al., 1993; Deconinck, Geyssant, et al., 1996; Deconinck and Baudin, 2008).

Location of the area studied here in the Boulonnais area. Maps and photograph from the Geoportail website of the French Institut Géographique National.

This study aims to broaden our understanding of the transitional, screening, way-through that the coastal zones are. As reminded above, efforts have mainly focused on the fate of organic matter in estuarine and coastal sediments, with the aim of better understanding this compartment or stage of the carbon cycle. Progress can still be made regarding the fate of iron in these specific environments. Iron and manganese have been extensively studied in coastal environments, particularly with regard to their involvement in the remineralization of organic matter, through phenomena such as the reduction of Fe and Mn oxyhydroxides, the reduction of sulfate ions and the formation of pyrite (e.g., D. J. Burdige, 2006; D. Burdige, 2011; B. B. Jørgensen et al., 2019). However, processes are examined through in vitro experiments and numerical modeling, but they are not observed in vivo: the situations are too complex because intertwined biotic and abiotic phenomena occur simultaneously, being almost impossible to decipher. Furthermore, the literature emphasizes the coupled reduction reactions of sulfate ions and metal species, which logically leads to the study of the formation of iron sulfide minerals such as mackinawite or pyrite (e.g., Rickard, 2012; Rickard, 2024). This type of work has not been so much interested in the genesis of glauconite or magnetite, and this is what this paper aims to address. The present work is justified insofar as it highlights the complexity of the relationships between iron-bearing minerals such as pyrite, glauconite, magnetite and hematite. Indeed, these relationships are again difficult to observe in vivo since they occur at intermediate time scales which most often escape direct observation: on the one hand, in situ observations require instrumentation that is difficult to set up, and little data exists to our knowledge; on the other hand, when ancient deposits can be observed in outcrop, the traces of the existence of transitory and fragile mineral phases have long since disappeared. The results of the present study show in particular that the transformations between pyrite and glauconite can occur in both ways, sometimes successively. This work also shows that diagenesis can lead to a selective disappearance of certain forms of glauconite grains, in particular those presenting the lowest maturity, which questions our understanding of the formation and evolution of this mineral.

2. Material and methods

The Kimmeridgian and Tithonian geological formations visible along the Boulonnais coastline were deposited on the shallow continental platform (shoreface to lower offshore) terminating the eastern part of the London-Brabant Basin (Mansy, Manby, et al., 2003). These deposits correspond to a succession of sandstone formations (shoreface) and marl formations (offshore). See detailed descriptions in Mansy, Guennoc, et al. (2007) and Deconinck and Baudin (2008). For the present study, the focus is set on the transition between the underlying Grès de Châtillon Fm. (Eudoxus ammonite zone, Contejeani sub-zone) and the overlying Argiles de Châtillon Fm. (Autissiodorensis sub-zone, i.e., the lowermost sub-zone of the Autissiodorensis ammonite zone). The uppermost part of the Grès de Châtillon Formation is made up with sandstones and sands. The sandstones are in the form of meter-size concretions, passing laterally to unconsolidated sands (Figure 2). The sedimentary structures observed are cross-stratifications (hearing bone style) and bioturbations. The facies are interpreted to represent shallow shoreface-type environments. The topmost part of the Grès de Châtillon is an uncemented level of rust-colored sand, rich in small shell fragments and woody remnants. The boundary between the Grès de Châtillon et Argiles de Châtillon formations is a whitish carbonate bed of authigenic origin (Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Vidier, et al., 2014; Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Sansjofre, et al., 2016). The Argiles de Châtillon starts with a meter-thick claystone bed (Figure 2), corresponding to offshore conditions (Deconinck and Baudin, 2008; Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Sansjofre, et al., 2016).

(A) Picture of the basal claystone level of the Argiles de Châtillon Fm. (1), overlying the top part of the Grès de Châtillon. This latter is almost not cemented except for rounded concretions (2 & 3). The whitish level separating the two formations is illustrated with the lower part of (B), together with the orange-color topmost level mentioned in the text, as well as herring bone-like structures (1) and synsedimentary fault (2).

The upper part of the Grès de Châtillon Fm. underwent syndepositional tectonic movements (Supplementary Material Figure S2 Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Vidier, et al., 2014; Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Sansjofre, et al., 2016). The synsedimentary faults were of small dimensions (Figure 2) or medium dimension (Figure 3), and they affected mainly the transition zone between the two formations at stake here (namely, the Grès de Châtillon and overlying Argiles de Châtillon). Well visible at the place called Cran du Noirda, north of Audresselles, the synsedimentary fault clearly cuts the sandstone concretions. It means that, when the displacement occurred, the sand was locally already indurated enough to get clearcut and remain so. In addition, the fault movements induced some injections of soft sand into indurated sand blocks (Figure 3; Supplementary Material Figure S2; Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Vidier, et al., 2014; Averbuch and Guillot, 2015). It means that the sand blocks were already indurated but not lithified yet, because water-impregnated soft sands could be injected into the concretions being formed. Complete cementation must have occurred short after, to account for the preservation of these structures (clearcut fault planes and sand injectites) over geological times. Such sand injectites are observed close to each synsedimentary fault affecting the stratigraphic episode discussed here, between Audresselles and the place called Pointe du Ridden, along the coastline (Figure 1). The synsedimentary movements also induced another type of sand injection. Meter-scale lobes of sand were injected from the underlying uncemented sand levels of the Grès de Châtillon Fm., through the calcareous transition bed, and into the basal claystone level of the Argiles de Châtillon Fm. (Figure 4). These injected lobes of sands are still uncemented today.

Structures pictured at the Cran du Noirda (see Figure 1) accompanying the synsedimentary fault movement. (A) Indurated injectites visible on the cemented nodules. (B) The fault plane itself, also visible in Figure 1), affecting the transition zone between the Grès de Châtillon and Argiles de Châtillon formations. The fault cut some sandstone nodules (lower arrow in B, C). (D) A soft sand injective penetrating the Argile de Châtillon Fm.

Sand injectites in the lower part of the Argiles de Châtillon Formation fueled by sand from the underlying Grès de Châtillon Formation. (A) The arrows point to unconsolidated sand lobes injected into the base of the Argiles de Châtillon Fm. Circle: a wooden folding meter for scale, on top of the whitish level separating the two formations. (B) Close up view of the sand injected into the basal marly bed of the Argiles de Châtillon Fm., with relicts of the marly beds embedded within the sand.

The sampling for the present study was carried out at the Cran du Noirda and Cran Mademoiselle (north to Audresselles town; Figure 1). Several facies were sampled: (1) uncemented, soft sand (4 samples) and cemented sandstones (7 samples of concretions and sand injectites) of the Grès de Châtillon, and (2) soft sand injectites (4 samples) and their hosting clay stones (4 samples) in the basal part of the Argiles de Châtillon.

Thin sections of the sandstones have been made and observed through a photonic microscope. The procedure for the extraction and analysis of the glauconite grains is detailed in Tribovillard, Bout-Roumazeilles, Abraham, et al. (2023), Tribovillard, Bout-Roumazeilles, Guillot, et al. (2023). In a few words, the samples were treated with an acid solution of HCl to digest the carbonate cement and release all the non-HCl soluble particles. The clay faction was removed through repeated rinses. The particles thus extracted were then oven dried before magnetic separation using a Frantz Isodynamic apparatus to collect the particles sensitive to magnetic separation (namely, here, glauconite a priori). The particles were imaged using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with a EDS-type analytical probe (FEI Quanta 200 SEM equipped with a Quantax QX2 Roentec energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy system). The grains were also analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) to determine their mineralogy according to the standard protocol described in Bout-Roumazeilles et al. (1999) and Tribovillard, Bout-Roumazeilles, Delattre, et al. (2021). XRD was carried out on both oriented mounts and non-oriented mounts to fully discriminate glauconite from illite. Raman microspectroscopy was performed with a JY Horiba, Labram HR800UV, equipped with an electronically cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) detector, using 532 nm laser excitation. Spectra were obtained using 100× magnification objective.

3. Results

The observation of the thin sections of sandstones yields the presence of dominant quartz grains, accessory glauconite grains, and some green-stained quartz grains, all of them being cemented with calcite (Supplementary Material Figure S1). The cement is made with equant spar drusy mosaics and poikilotopic spar. Some tiny, brown color, rhombs of dolomite are observed.

After HCl leaching and clay size-mineral elimination, the X-ray diffraction analysis showed that all the green clay minerals examined here are glauconite stricto sensu (Supplementary Material Figure S3), as was the case in all our previous studies (Tribovillard, Bout-Roumazeilles, Delattre, et al., 2021; Tribovillard, Bout-Roumazeilles, Abraham, et al., 2023; Tribovillard, Bout-Roumazeilles, Guillot, et al., 2023). Raman spectrometry showed that magnetic minerals (reactive magnets), other than glauconite, are made up of magnetite, which is associated with apatite. The populations of grains may be described according to their response to magnetic separation. First, the fraction of the sediments or rocks that are not sensitive to magnetic fields is made of quartz grains, pyrite framboids and small-dimensioned wood fragments, plus rare, unidentified accessory minerals, also termed “heavy” minerals. Second, the magnetic-field sensitive fraction consists of glauconite and magnetite grains, both minerals being sensitive to magnetic fields, plus green-stained quartz, pyrite framboids and small dimension, pyritized, wood fragments. Quartz, pyrite and wood fragments are not sensitive to magnetic fields, therefore, their presence in this fraction of rocks implies that they are closely associated with a mineral sensitive to magnetic fields. Visibly, the green-stained quartz grains must be associated with glauconite and this may also be true for the pyrite and woody particles. The associated magnet-sensitive phase may also be magnetite.

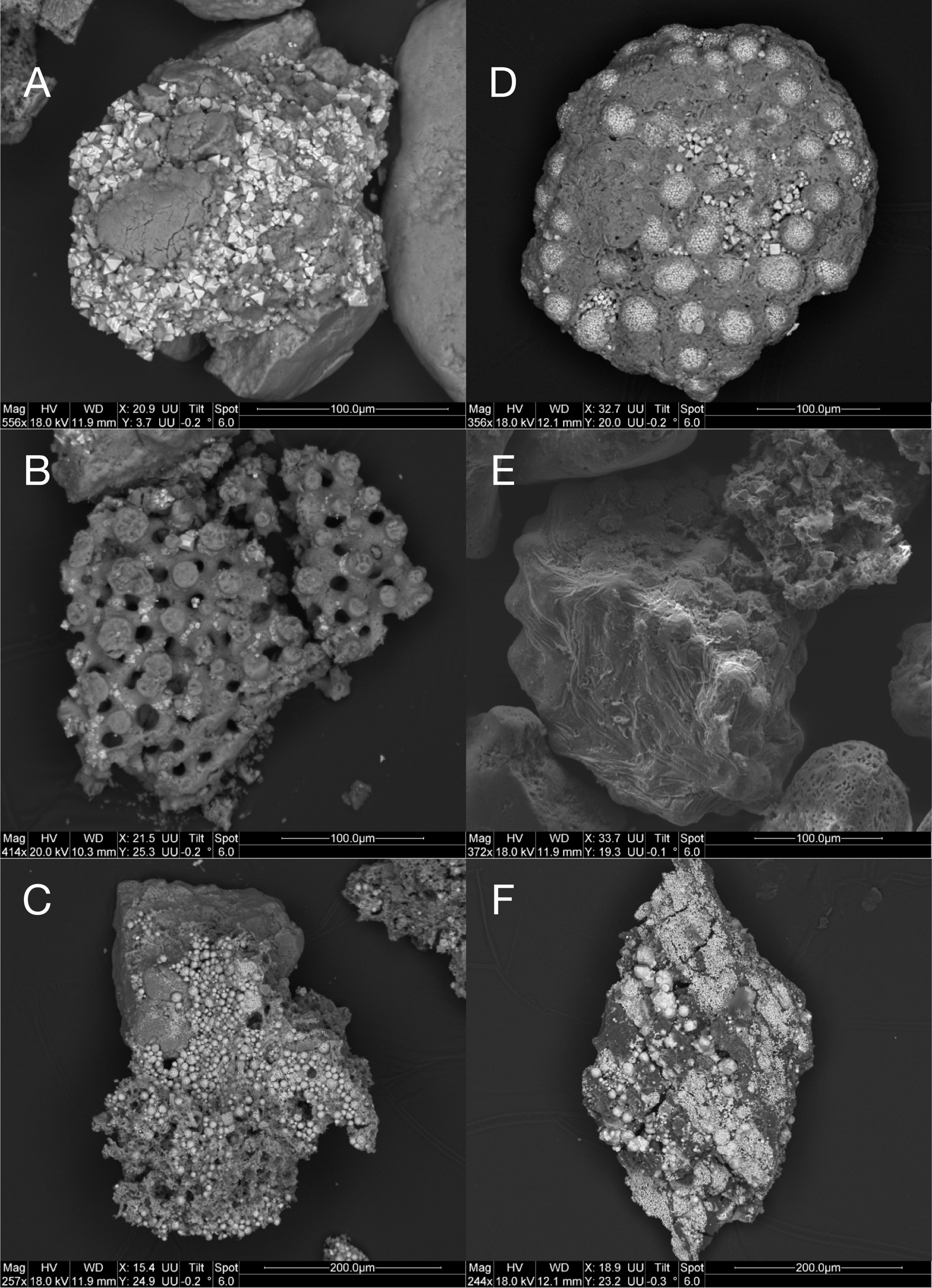

The magnet-sensitive fraction may be distinguished according to the facies into three categories: cemented sandstone blocks and injectites of the Grès de Châtillon, soft injectites pushed into the basal claystones of the Argiles de Châtillon Fm., and the sandy material still in place, which fueled the various injectites and that has not been cemented (Table 1). Hereinafter, these three facies will be termed sandstones, soft injectites and sand, respectively. Glauconite grains are commonly observed in the sandstones and in the soft injectites, but only rarely in the sands. Some differences are detected between the two facies bearing abundant glauconite grains. In the sandstones, the glauconite grains show a gradation of colors, from pale green to dark green, almost black, whereas the glauconite grains are all dark green in the soft injectites. A grain size gradation is also observed using SEM images (we were unable to use a laser-equipped grain sizer because of a too-small number of glauconite grains). The range of the glauconite grains is wider toward small dimension particles in the sandstones than in the soft injectites where only large grains are presents (Figure 5).

Specific content of the three facies considered in this study

| Uncemented sands | Soft injectites (uncemented) | Cemented injectites and sandstones |

|---|---|---|

| Magnet-sensitive quartz grains frequently stained with glauconite | Magnet-sensitive quartz grains frequently stained with glauconite | Magnet-sensitive quartz grains frequently stained with glauconite |

| Magnet-sensitive wood fragments, sometimes associated with altered pyrite | Magnet-sensitive wood fragments, frequently associated with altered pyrite | Magnet-sensitive wood fragments, almost always associated with fresh pyrite and/or glauconite |

| Rare non magnet-sensitive wood fragments | Common non magnet-sensitive wood fragments | Frequent non magnet-sensitive wood fragments |

| Rare dark green (almost black) glauconite grains with relatively narrow size distribution | Frequent dark green (almost black) glauconite grains with relatively narrow size distribution | Abundant glauconite grains with a color array from light green to black, and a wide grain-size distribution |

| Not observed | Not observed | Abundant glauconitized bryozoans (light green, large sized) |

| Not observed | Not observed | Common small-dimensioned automorphic magnetite grains |

(A) A population of magnet-sensitive particles after magnetic separation, showing a relative wide array of green colors. Noteworthy, the presence of quartz grains and a pyrite polyframboid. (B, C) SEM images of the particles, with notably a pyritized wood fragment and a glauconitized bryozoan (C). (D) The peculiar grain with sort of endolithic filaments, looking like a microbial structure. (E, F) Glauconitized bryozoans. Sometimes, the grains are almost coated with glauconite (F). If complete, the coating would give the visual impression of a solid grain.

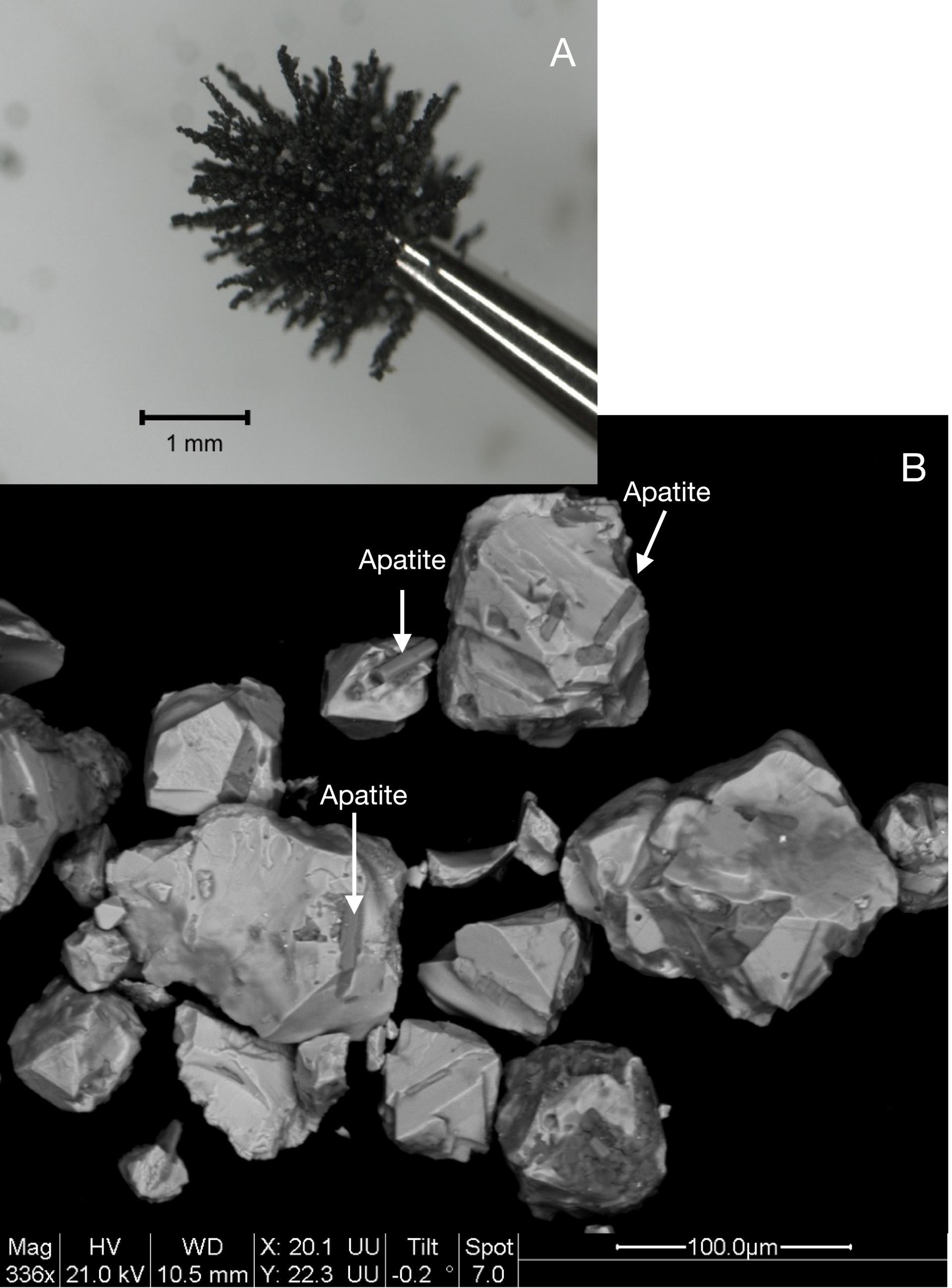

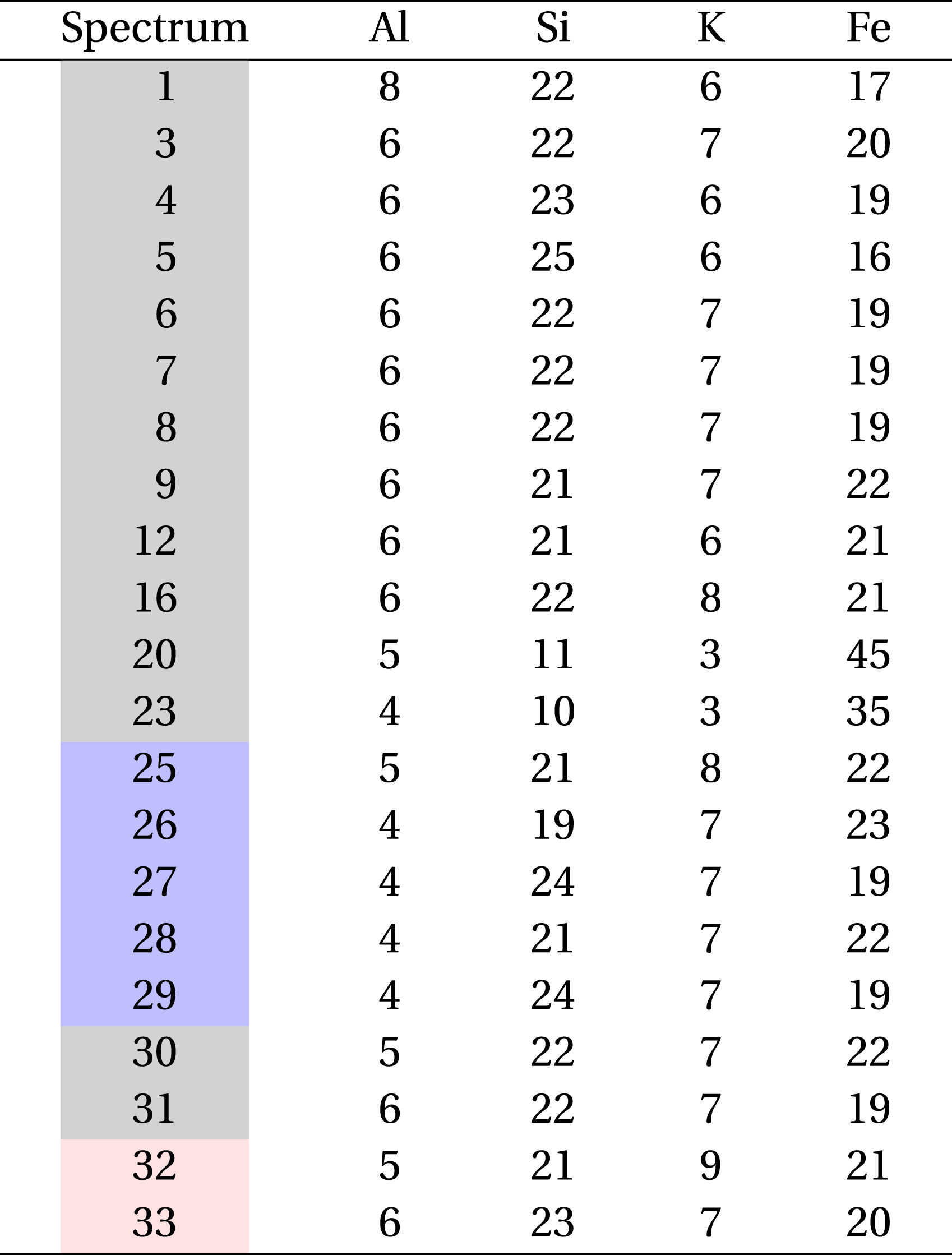

In addition, peculiar grains display specific structures of evident biological origin (Figures 5B, C, E, F and 6B). The peculiar grains are most probably glauconitized fossils of bryozoans (cyclostomes ?); see for instance Haddadi-Hamdane (1996) and Hara and Taylor (2009). Most often, glauconitized bioclasts are echinoderm fragments, and glauconitized bryozoans are seldom mentioned (e.g., Giresse et al., 1980) and when it is the case, glauconite occurs as chamber infilling rather than the results of microstructure epigeny (Banerjee, Chattoraj, et al., 2012; Banerjee, Bansal, Pande, et al., 2016; Banerjee, Bansal and Thorat, 2016; Bansal, Banerjee, Pande, et al., 2020; Mohammed et al., 2025). The SEM image shown Figure 5F illustrates one type of grain commonly observed in the sandstones, that is, worn glauconite disclosing their inner structure that seems to be a fossil bryozoan colony. An intriguing particle was observed (Figure 5D; Table 2 for EDS analyses), yielding an inner structure made of glauconite-made filaments, which evokes microbial structures. The microbial origin cannot be ascertained and only one such grain was identified. Accordingly, another sample exhibited a peculiar structure, as if a framboid of pyrite had been wrapped with a glauconitized film; this biofilm looks like a microbial biofilm (Figure 6E and Table 2 for EDS analyses). Thus, in addition, to glauconitized bryozoan fossils, our observations allowed us to identify rare and odd structures, resembling microbial filaments and biofilms. More frequently, many grains are made with pyrite and glauconite tied together, as well as intricate wood fragments and glauconite or pyrite (Figures 6A–C and F). Pyrite is in the form of framboids and polyframboids, and/or euhedral crystals. Pyrite may have grown onto glauconite grains (Figures 6A, B) but the converse is also true, with glauconite having in some way coated pyrite framboids (Figure 6D). Many wood fragments are pyritized, as illustrated in Figure 6F. The fact that such pyritized objects are magnet-sensitive implies that a sensitive mineral phase is in association because pyrite does not react to magnetic fiels (at room temperature). Some ferrimagnetic grains were extracted using a simple magnet. As shown with Figures 7A and B, the grains are of small dimensions and dominantly euhedral. SEM analysis using EDS indicates that these grains are made with magnetite and euhedral apatite crystals are associated with magnetite (Figure 7B). In our samples, magnetite was not associated with glauconite nor pyrite.

SEM images of the chronology of the growth of authigenic minerals. (A–C) Pyrite (whitish or light grey) tetrahedrons or framboids over glauconite grains or bryozoans (dark grey). (D) The dark grey glauconite developed over a polyframboid of pyrite, and tetrahedrons or octahedrons of pyrite grew in turn over the glauconite. (E) A sort of glauconitized sheet wraps a pyrite polyframboid. (F) Pyritized wood fragment.

(A) Magnetic minerals surrounding the tip of a steel needle. (B) SEM image of the magnetite grains bearing authigenic apatite (elongated, dark grey crystals indicated with arrows).

Chemical analyses (through EDS-equipped SEM) of glauconite particles, expressed in weight %

|

In the soft injectites, the mineral assemblage sensitive to magnetic fields is less diversified (Table 1). No magnetite and no glauconitized microfossils or microstructures were observed. Only smoothsurface, dark-green, glauconite grains are present and their size range is narrow compared to the grains of the sandstones. In addition, magnet-sensitive quartz grains and wood fragments are common. The magnet-sensitive wood fragments are frequently associated with altered pyrite. The remaining components of the soft injectites, that is, the fraction that is not sensitive to magnetic fields, are quartz grains and more or less abundant wood fragments (Figures 5B, C).

The sands of the topmost part of the Grès de Châtillon Fm. are hosting lithified sandstone blocks and they fed the soft injectites (Figure 2). Their mineral composition is even poorer, relative to the first two facies: quartz grains are dominant, accompanied by accessory wood fragments. Glauconite grains, magnet-sensitive, green-coated quartz grains and wood fragments associated with altered pyrite are rare. At the boundary between the Grès de Châtillon and Argiles de Châtillon formations, the topmost sand bed is orange-colored and rich in bioclasts. Through photonic or electronic microscope observation, the orange particles look like small flakes or altered framboids, made of iron oxides as evidenced by EDS analysis.

4. Interpretations

4.1. Fast forming authigenic minerals

The mineral composition of the three facies discussed here is contrasted in terms of authigenic-grain preservation through early diagenesis. As reminded above, the sandstones and lithified injectites were cemented during the earliest diagenesis. The hosting sands have not been cemented and display a poorer mineral composition compared to the sandstones. However, being lateral equivalents, both facies were identical from a compositional point of view, at the time of sediment deposition. Therefore, the early cementation of some parts of the sand deposits sealed the pore space, thus preventing further fluid circulation and thence, fragile grains were protected against dissolution. Thus, magnetite and rounded, pellet-like, glauconite grains were preserved from oxidation, together with the peculiar glauconite grains showing an inner structure: bryozoan fossils and the grains looking like microbial structures (filaments and wrap). Accordingly, small glauconite grains, with a relatively large specific surface, were also preserved. All these objects cannot have formed during later diagenesis, because the sealed porosity must have prevented any subsequent mineral precipitation by suppressing any ion supply via pore fluids. Consequently, the fact that these objects were already present prior to early cementation evidences that glauconite and magnetite formed during the earliest diagenesis steps. It thus confirms that under certain circumstances, glauconite may be a fast-forming mineral. On the contrary, in the uncemented sands, where fluid circulation could take place, all these fragile objects disappeared (including the smallest glauconite grains), and together with them, the record of some benthic organisms, i.e., in the present case, bryozoans. The soft injectites seem to be an intermediate situation. The sandy material that was injected into the claystones must have been the same as that present in the sands and sandstones of the grès de Châtillon Fm. This material has been caged within a level of sediments with low permeability but it was not sealed by a cementing phase. Thus, fluid circulation was possible and the injected material was only partly sheltered from oxidation.

The fact that fluid circulation must have been a little bit easier within the basal level of the Argiles de Châtillon compared to the sealed sandstones and lithified injectites is important to determine the time when glauconite and magnetite were formed: before injection or after it? Did the material of the soft injectites already contain grains of magnetite or glauconite, or did these grains appear later in the injected material? The authigenic formation of such grains requires dissolved ions being available in pore fluids. As magnetite and glauconitized bryozoans are absent from the soft injectites, it is suggested that the authigenesis of these two minerals was not possible in this medium, to be put in relation to the low permeability of the claystones at the base of the Argiles de Châtillon. A fortiori, as said above for early lithified materials, such authigenesis would have been even more hampered in a medium being sealed precociously through early cementation. Consequently, it is inferred that glauconite and magnetite appeared during the earliest diagenesis, prior to any synsedimentary fault movement. Later, while some localized places within the sands were undergoing incipient cementation, some syndeposit movements triggered the injection of sands either at the uppermost level of the Grès de Châtillon or in the lowermost level of the Argiles de Châtillon. The sands thus injected into sandstones being cemented were also cemented almost contemporaneously, and therefore, protected from further fluid circulation. Their authigenic content was “locked” and this memory kept intact. Besides, the sands injected into the Argiles de Châtillon were not so well protected from further exchanges with fluids, and only part of their authigenic content was preserved (partial loss of memory). Magnetite and bryozoan fragments disappeared, as well as small glauconite grains. Lastly, the uncemented sands of the uppermost part of the Grès de Châtillon were washed drastically through time, losing almost any evidence of the authigenic phases but rare, dark-green colored glauconite grains (an almost complete loss of memory). The fact that only dark-green coloured grains are observed suggests that the light-green and pale-grey glauconite grains, which are the immature ones, had more porosity in them to alter and get removed from the sands (Baldermann et al., 2013).

A first information is that within such shoreface sands, authigenic phases can develop during the earliest steps of diagenesis. This point must be stressed on, with respect to glauconite. This work reinforces the growing view considering that glauconite grains can form in a wide range of marine environments and of durations (from the earliest diagenesis to millions of years; Banerjee, Mondal, et al. (2015), Banerjee, Bansal, Pande, et al. (2016), Banerjee, Bansal and Thorat (2016); Tribovillard, Bout-Roumazeilles, Guillot, et al. (2023), Tribovillard (2024) and references therein). Nevertheless, the earliest diagenesis is not a quantified duration per se. To refine a bit the datation, an on-going study of the age of the carbonate cements of the Jurassic sandstones of the Grès de Connincthun Fm. must be mentioned (Blaise et al., 2025). This formation is older than the Grès de Châtillon: Aspidoceras caletanum ammonite zone of the middle Kimmeridgian (Mansy, Guennoc, et al., 2007). This formation was also affected by synsedimentary movements accompanied by fluid seepages that induced an early cementation (Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Vidier, et al., 2014). The paper by Blaise et al. (2025) reports U–Pb datations yielding an age of est 148.9 ± 5.7 Ma, that is, very close to the Kimmeridgian–Tithonien boundary, according to the 2024/12 version of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart (https://stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2024-12.pdf). Such results cannot be over interpreted. It may just be stated that the cements probably induced by fluid circulations have about the same age as that of the early lithified objects at stake in this paper. These results give support to the interpretations of Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Vidier, et al. (2014) about fluid circulation but the precision of the ages is not adapted to the questions at stake here.

4.2. Pyrite and glauconite co-occurrence

Our SEM observations show that pyrite may have grown onto glauconite as well as glauconite may have coated, or even wrapped pyrite framboids. Accordingly, because pyrite must not react to magnetic fields, if pyrite particles and pyritized wood fragments are sensitive magnets, it may be inferred that a part of their pyrite load has been converted to glauconite (or magnetite). Whereas the pyritization of wood fragments is rather common (e.g., Rickard, 2012), the close association of glauconite and pyrite is seldom reported (Fanning et al., 1989; Rabenhorst and Fanning, 1989). Pyrite is a mineral where iron is present in its reduced form. Glauconite and magnetite contain simultaneously the reduced and the oxidized forms of iron (Fe2+ and Fe3+). Therefore, the formation or growth of these authigenic minerals results from contrasted redox conditions. As a consequence, the observed co-occurrence of pyrite and glauconite suggests that these authigenic minerals must have fed on a common pool of iron. However, following slight redox variations within the pore space, the presence of dominant Fe(II) would have led to pyrite precipitation, whereas an iron pool with both Fe(II) and Fe(III) coexisting would have induced the formation of glauconite (and magnetite). In addition, the presence of pyrite growing on glauconite as well as glauconite growing on pyrite implies that the redox conditions were fluctuating in both ways within the pore space during the earliest diagenesis, prior to cementation (Canfield and Berner, 1987; Suk et al., 1990; Brothers et al., 1996; Roberts, 2015; Runge et al., 2023).

4.3. A bio-induced origin?

Some rare glauconite grains allow a microbial structure to be hypothesized: bacterial filaments, fungi, or an abiotic phenomenon that mimics a biological structure (Figure 5D). Besides, pyrite framboids wrapped by biological biofilms, such as the structure visible in Figure 6E, has already been reported (Rickard, 2021) but it is the first time, to the best of our knowledge, that such a biofilm made of glauconite is reported. The biofilm looking so thin must have been delicately mineralized through the ion by ion replacement called epigenization. It is also the first time that such glauconite-made filamentous structures are reported. It may be wondered whether glauconite fossilized biological (bacterial?, fungal?) structures or whether microbial activity induced glauconite precipitation. In addition, SEM images show that magnetite and apatite are intricately associated, showing euhedral morphologies typical of authigenic formation. Such a mineral association is not uncommon and may be interpreted as the result of bacterially mediated reactions, e.g., dissimilatory iron reduction (Hu et al., 2025). As a consequence, a bundle of concordant clues suggests that the authigenic processes highlighted in this study are directly linked to microbial activity.

The role of bacteria in the formation of sedimentary pyrite is beyond doubt (Rickard, 2012; Rickard, 2024) but this role is not considered in the genesis of glauconite. Nevertheless, Geptner et al. (2017) reported the formation of finely dispersed glauconite within algal borer trails and holes, in Oligo-Miocene sediments of Kamchatka. In addition, bacterial activity is involved in the redox reactions affecting the iron pool of the pore space (iron(II)-oxidizing bacteria or IOB, as well as iron(III)-reducing bacteria or IRB; e.g., B. B. Jørgensen, 2006; Miot and Etique, 2016; Rickard, 2024). Consequently, the interrelationships of IOB and IRB within the pore space must have made iron(II) and/or iron(III) available for the authigenic formation of various iron-bearing minerals (glauconite, magnetite, pyrite) following subtle variations in the redox status at so little scale (Mathon et al., 2024; Vosteen et al., 2024). This indirect role of bacteria, via iron chemistry, together with the presence of some structures strongly resembling bacterial features mentioned above, allow us to question the possible role of bacteria in the formation of glauconite.

4.4. Organic matter remineralization and oxygen consumption

Small dimension woody fragments are common to frequent in the facies studied here. They are less abundant and less well preserved in the sands than in the soft injectites and in the sandstones. The presence of such recalcitrant organic products is expected, because fragile (also termed labile) organic compounds are rapidly remineralized in such coarse sediments (e.g., Tyson, 1995). Sands being a porous and permeable milieu, oxygen-deprived conditions, inducing reducing conditions, are not expected to develop. Nevertheless, the presence of reduced iron-bearing minerals in the sandstones testifies to the development of reducing conditions in the pore space during very early diagenesis, most probably resulting from organic matter respiration or remineralization. The presence of scattered pyrite means that sulfide-reducing bacteria were locally thriving, probably accompanied by other bacterial consortia (B. B. Jørgensen, 2006), all of these being heterotrophic and therefore, consuming organic matter. Such bacterial populations usually do not use woody fragments, favoring labile organic products. Nevertheless, the woody fragments are less frequent in the sands, compared to the other two facies, namely, soft injectites and sandstones. This observation could be accounted for by the priming effect (Bianchi, 2011; Yang et al., 2023). Whether the priming effect was the cause or not, our observations suggest that the unconsolidated sands were an environment that made possible the loss of part of the pool of recalcitrant woody organic matter, in addition to all of the fragile organic material. Incidentally, such reactions to degradation of recalcitrant or labile organic matter may account for the fact that the shoreface sandstones are so frequently lean for organic matter, although biological production and activity are intense there. On the other hand, when the sediments have been “frozen”, one might say, by early cementation, the provisional richness in organic debris of these sands can be observed.

4.5. The shoreface environment, a trap for iron?

This study evidences how reactive the shoreface environment may be, with respect to early diagenetic, microbially mediated or -related, reactions involving iron. The uncemented sands yield an expected mineralogical composition with dominant quartz grains, wood fragments and some accessory minerals, e.g. glauconite grains. However, early diagenesis, when it locked the pore space and turned the sands into early-cemented sandstones and injectites, has somehow “frozen” the situation as it was shortly after the sediment was deposited. Thanks to this “snapshot”, all the consequences of the biogeochemical activity of this sedimentary environment can be observed and highlighted. Notably, iron-bearing minerals bear witness to this intense activity. It is thus visible that, although the shoreface sediments are porous and permeable, that is, favorable to aerobic conditions and oxidizing reactions, redox conditions can turn rapidly to suboxic or anoxic, allowing pyrite, glauconite and magnetite to develop simultaneously or successively. Such diagenetic reactions trapped reactive iron. As they occurred shortly after deposition, iron was trapped early, at the depth below the seafloor where grains are no longer mobile and where the dissolved oxygen consumed by organic decay is not replenished fast enough, all this ending with suboxic/anoxic conditions. If such sands are not cemented fast enough, they will release the trapped iron, leaving sandstones showing the typical assemblage of quartz, wood fragments and calcitic bioclasts (plus possible accessory minerals).

The following two questions may arise: (1) why did (do) these authigenic minerals disappear during subsequent steps of diagenesis?, (2) why did the sands get cemented early? As regards to the first question (1), it is expected that, within the sands not lithified yet, once all the reactive, labile organic matter is consumed, the porous and permeable milieu prevents suboxic/anoxic conditions to maintain. In addition, under oxygen-deprived conditions, denitrifying bacteria are able to oxidize pyrite, while other microbial population reduce Fe3+ and Mn4+ ions through pyrite oxidation (C. J. Jørgensen et al., 2009). Magnetite and glauconite may thus turn into iron oxides (e.g., hematite). Such rust-colored oxides are abundant in the topmost 15 cm of the Grès de Châtillon (Figure 2B). This peculiar rusty level does not result from supergene weathering by either meteoric water or seawater: as a matter of fact, first, it is sheltered from per descensum meteoric circulations by the thick, overlying, claystone and shale accumulations of Kimmeridgian and Tithonian ages. Second, the erosional retreat of the coastline maintains the freshness of the outcrop and this level can be observed with the same visual characteristics all along the coastline between the Pointe du Ridden and the Cap de la Crèche, that is, between the Cap Gris Nez and the city of Boulogne-sur-Mer (Figure 1). As regards to the second question (2), a common way for sands to get lithified early is the lithification process known as beachrock (Tucker and Wright, 1990; Neumeier, 1999; Hibner et al., 2025) but the Grès de Châtillon does not match this case: rock thin sections do not show early cements but equant spar drusy mosaics and poikilotopic spar cements. In the Boulonnais area, all the fine-grained carbonate beds (therefore excluding the numerous coquina beds) and carbonate nodules of the Jurassic formations studied so far resulted from bacterially mediated, early diagenetic precipitation of CaCO3. The bacterial activity was fueled by cold, methane-bearing, fluid seepages. The seepages were linked to synsedimentary tectonic movements (Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Vidier, et al., 2014; Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Sansjofre, et al., 2016). It can be hypothesized that the same mechanism applies to the sandstone at stake here (Blaise et al., 2025). Whatever the cause of the early cementing, the present works highlights the cornerstone importance of such early-lithified objects to visualize and identify the fauna (here bryozoans) and authigenic minerals (glauconite, magnetite) initially present and since disappeared. Authigenic carbonate beds, nodules, concretions, septaria, early cemented sandstones (plus, here, lithified injectites) are thus useful (if not essential) tools for reconstructing paleo-ecological or -environmental conditions during deposition or shortly after it.

4.6. Estuarine environments

Here it is insisted on the fact that the redox degree may condition the variety of authigenesis: pyrite is forming when iron is dominantly in the reduced form, glauconite and/or magnetite when iron is present both in the reduced form and the oxidized one. In sedimentary environments, pyrite results from sulfate reducing reactions, induced by microbial activity (see D. J. Burdige (2006) or Rickard (2012) for reviews). The formation of glauconite and/or magnetite implies that sulfate reduction was not complete (otherwise, iron would have been entirely turned into Fe(II)). Such a limitation of sulfate reduction can result from the redox status or from the sulfate pool itself. Sulfate abundance could be the limiting factor and sulfate limitation could be due to dilution by freshwater. The Boulonnais area is interpreted to have been close to a (large?) estuary Hatem, Tribovillard, Averbuch, Bout-Roumazeilles, et al. (2017); therefore, a dilution of the seawater (and its sulfate content) cannot be ruled out. This statement is based on assumptions and might look like a bit speculative; nevertheless, our hypothesis is worth exploring. Modern occurrences of authigenic glauconite grains encompass many estuarine and littoral environments (e.g., Chafetz and Reid, 2000; El Albani et al., 2005; Banerjee, Mondal, et al., 2015; Banerjee, Bansal, Pande, et al., 2016; Banerjee, Bansal and Thorat, 2016; Bansal, Banerjee, Ruidas, et al., 2018; Rubio and López-Pérez, 2024, to mention a few). To give some support to the hypothesis, it may be reminded that dolomite can be observed in thin sections. Dolomite may have several origins and one of them is linked to sulfate limitation (e.g., Tucker and Wright, 1990). Consequently, estuarine environments, with their freshwater inflow, may have been specific places over geological times, favorable to the rapid authigenic formation of glauconite grains, provided reactive iron was present. Of course, this scheme does not preclude the existence of other mechanisms and environments prone to authigenic glauconite (e.g., see Giresse, 2022, for a review).

4.7. Life on Mars?

The title is a bit provocative but NASA reported the presence of sandstone nodules beside the so-called “Nankluft Plateau” on Mount Sharp on the planet Mars (image from Curiosity Mast Camera; https://assets.science.nasa.gov/dynamicimage/assets/science/psd/mars/downloadable_items/3/9/39117_mars-rover-curiosity-sandstone-nodule-PIA20324.jpg). Such nodules could have recorded and “kept in memory” fleeting, short-lived, minerals such as those studied here, that may be related to biotic processes (e.g., Siljeström et al., 2024, and references therein).

5. Conclusions

Examining sediments where the pore space had been sealed during the earliest steps of diagenesis allowed us to highlight the following key points.

- Glauconite can form very precociously.

- If the role of micro-organisms in the formation of pyrite (and magnetite) is beyond doubt, the question for the formation of glauconite here appears to be entirely legitimate.

- The shoreface sands can be a milieu with unsuspected oxygen-poor conditions triggering the early precipitation of iron-bearing minerals. The iron trapped by these authigenic minerals is gradually released into the marine environment as they disappear due to the permeability of the hosting sands. The land-sea transition zone is therefore an important regulator of the iron flux to the ocean.

- Early cemented sediments are in such circumstances the memory of early diagenesis.

- Because they may limit the abundance of sulfate and, therefore, the intensity of sulfate reduction reactions, estuarine environments with a suitable reactive-iron load could be places prone to the formation of glauconite (and magnetite) grains.

In addition, it may be wondered whether the priming effect accounts for the degradation of recalcitrant organic matter in shoreface environment.

This work shows that early cemented sediments can record diagenetic steps that uncemented or lately cemented sediments are unable to “keep in memory”. For geochemists, carbonates are not good recorders of the diagenetic sequence because they make a system that is generally not well closed or sealed: for instance, upon recrystallization, they can release or incorporate elements or specific isotopes. In spite of such pitfalls, this study shows that early carbonate cementation is a pre-requisite to be able to infer paleoenvironment reconstructions of coastal, clastic dominated deposits and milieus. With a little audacity, one could even propose that the memorial quality of early cemented deposits makes them ideal targets for searching for traces of biological (microbial) activity on the planet Mars.

Acknowledgements

This work has been performed using the Plateform CARMIN – Ulille infrastructure and technical support. Our thanks go to the Programme Tellus Syster of the French Institut des Sciences de l’Univers (INSU) for funding our work. We thank Monique Gentric for the financial/administrative management, and Noe Frisch for the technical support of this project, as well as the LOG laboratory and the Department of Earth Sciences of the University of Lille for their support. We thank our referees for their useful and appreciated comments, as well as the CR Geoscience’s staff.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0