1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the timing and amplitude of the end of the African Humid Period (AHP) in tropical North Africa have been the subject of extensive debates. Was the transition from wet conditions that favored the expansion of tropical forest trees in the Sahel and the Sahara during the Holocene (Watrin et al., 2009) to the modern semi-arid and arid landscapes abrupt or gradual? While deMenocal et al. (2000) then Shanahan et al. (2015) identified the end of AHP in Sahara as an abrupt event around 5 ka, Kröpelin et al. (2008) and Lézine, Zheng, et al. (2011) showed that the humid-arid transition was more gradual, spanning between 4.3 ka and 2.7 ka. High-resolution records of past hydrological conditions and their impact on natural vegetation are scarce in the Sahel. However, the Atlantic coastline north of the Cape Verde peninsula in Senegal, known as the “Niayes region”, is one of the most well-documented areas. Several factors, including rainfall, sea-level variations, and groundwater behavior, have influenced the hydrology of this region during the Holocene, contributing to the complexity of local hydrology and distribution of natural vegetation (e.g. Chateauneuf et al., 1986; Lézine and Chateauneuf, 1991; Maugis et al., 2009; Putallaz, 1962). In 1989, Lézine demonstrated that this region underwent large-scale environmental changes, with the widespread expansion of tropical-humid gallery forests during AHP. Recent high-resolution geochemical and palynological studies (Fall et al., 2010; Lemonnier and Lézine, 2021; Lézine, Lemonnier and Fofana et al., 2019; Ndiaye et al., 2022) have shed new light on the chronology and amplitude of the collapse of these gallery forests at the end of AHP and the establishment of present-day landscape. This review presents Holocene data from the entire “Niayes region”, from the Cape Verde peninsula in the south to the mouth of the Senegal River in the north, with the aim of clarifying the different stages of the shift from humid to dry conditions at the end of AHP and the related collapse of forests. In the absence of archaeological data in this specific region—unlike the Senegal river valleys (e.g., Bocoum, 1986; McIntosh and Bocoum, 2000) and Falémé (Chevrier et al., 2016), or the Sine Saloum and Gambia river valleys (e.g., Camara et al., 2017; Laporte et al., 2017; Holl, 2022)—Paleoenvironmental changes discussed here are thought to be linked to rainfall change. Data from lakes and rivers in other regions of Senegal are used to provide a regional picture of environmental change at the end of AHP.

2. The Niayes region of Senegal

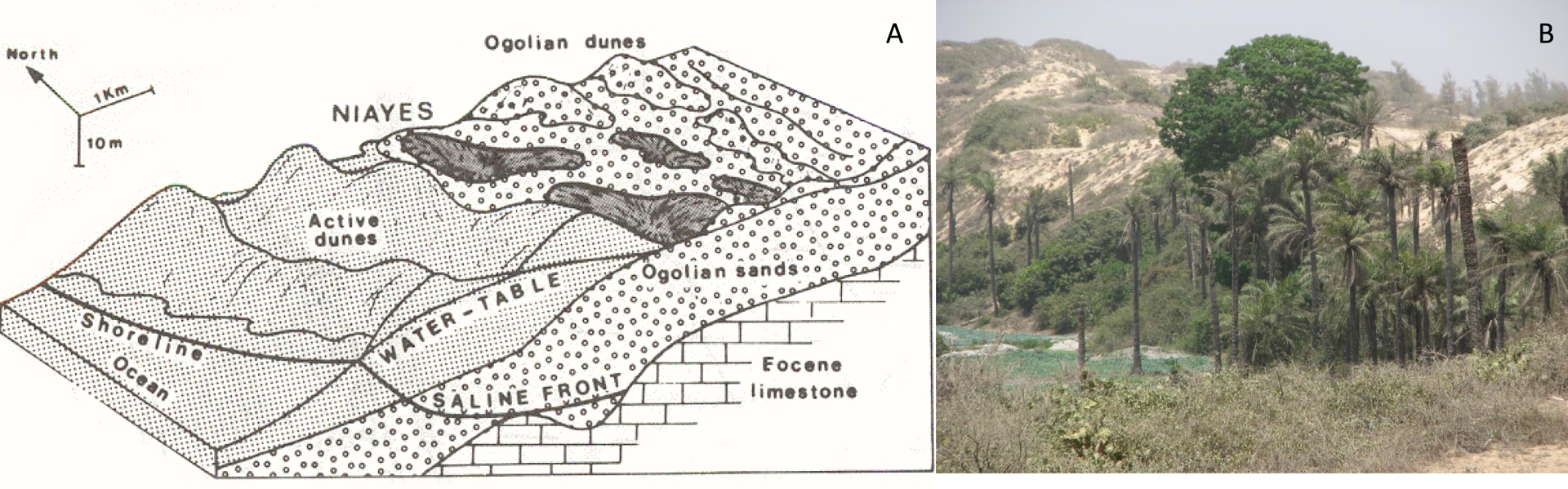

“Niayes” are interdunal depressions located behind the Atlantic coastal strand of Senegal, spanning roughly 15°N to 16°N. These small, isolated basins or elongated depressions perpendicular to the coast correspond to former channels whose outlets to sea have been obstructed by sand dune formations over the last millennia. Interdunal depressions support plant communities that include an extension of humid tropical forests to the north, favored by local moisture conditions and low evaporation along the coast. They form the “sub-Guinean domain” described by Trochain (1940), including oil palms (Elaeis guineensis) and other Guinean and Sudano-Guinean trees (Phoenix reclinata, Syzygium guineense, Alchornea cordifolia, Lophira alata …) that form gallery forests along water bodies (Figure 1B).

(A) Relations between fresh groundwater and salt-water front in Niayes (from Chateauneuf et al., 1986); (B) Guinean and Sudano-Guinean trees at dune’s foot in a Niaye. Dune tops are covered with steppic (Sahelian) shrubs and herbs.

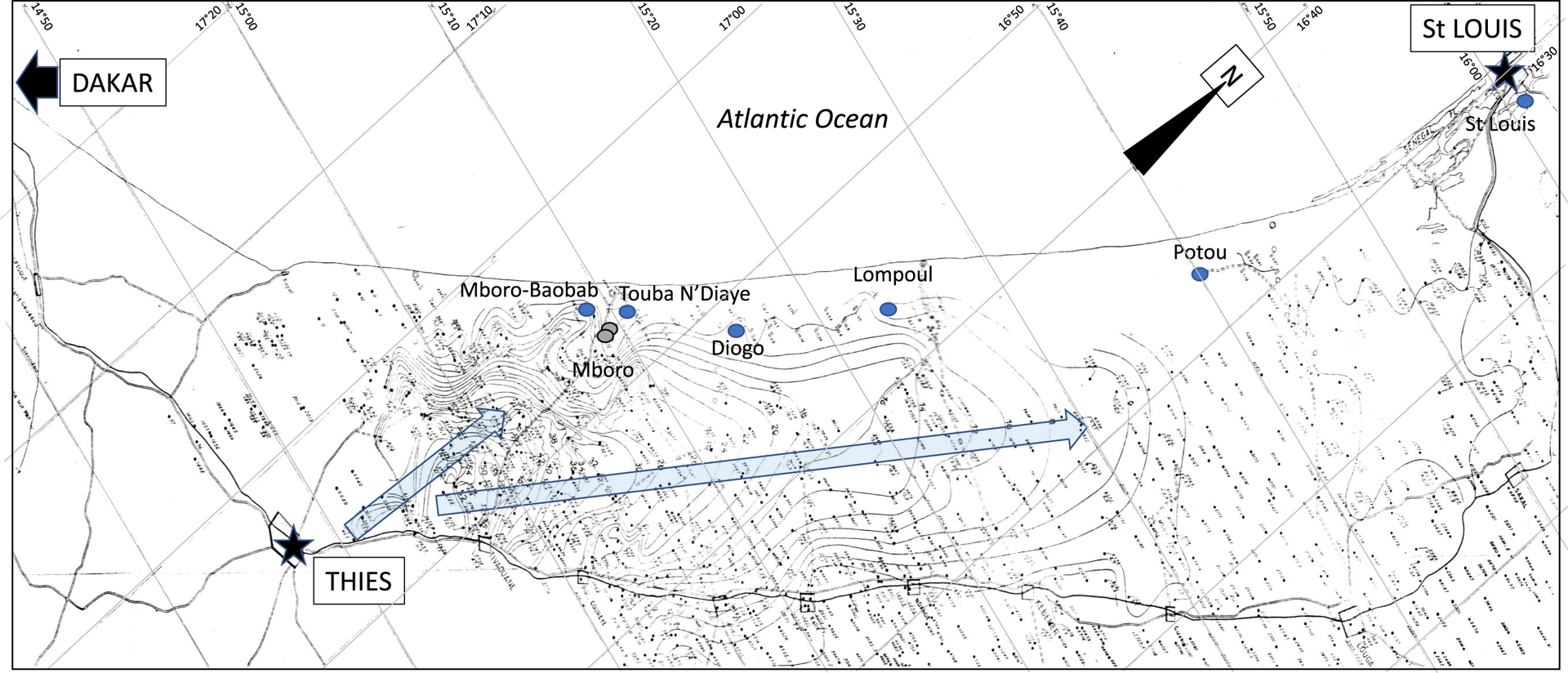

Today, the sub-Guinean domain of Niayes lies in an azonal position compared to the steppe vegetation of the inland Sahel. Tropical plants it contains benefit from a freshwater table close to the surface at the bottom of the interdunes. The level of this freshwater table mainly depends on the rainfall amount and sea-level position. Freshwater recharge originates from Thiès plateau located approximately 25 km to southeast and gradually decreases northward and westward (Figure 2). Contact between the freshwater table and seawater front reaches the surface along the beach, descending through Quaternary sands towards the internal littoral domain (Chateauneuf et al., 1986).

Piezometric map of the Niayes region in 1962 (Putallaz, 1962). Blue and grey dots show location of pollen and geochemical records cited in the text, respectively. Arrows indicate lowering of the water table from Thiès plateau.

Tropical humid forests were widely developed in the Niayes region during the African Humid Period (Lézine, 1988), due to heavy monsoon rainfall over West Africa (Lézine, Hély, et al., 2011). However, these forests are now severely degraded by agricultural and industrial practices, accompanied by heavy water table pumping, as well as the severe drought that occurred in the Sahel between around 1970 and 1980 (Aguiar et al., 2010).

3. Paleoenvironmental context

Specific environmental conditions in the Niayes region are influenced by two major factors: rainfall and sea-level variations.

3.1. Sea-level variations along the Senegalese coast

Numerous radiocarbon dates on marine mollusk shells and mangrove sediments have been used to reconstruct sea-level changes along the Senegalese coast (Faure et al., 1980). These dates indicate a gradual rise in the sea after the lowest level recorded during the Last Glacial Maximum (ca. −100 m, Vacchi et al., 2025), with modern level reached around 7000 years ago. The sea-level then fluctuated within a small amplitude of plus or minus 2 m (Faure et al., 1980). However, due to the low elevation in the coastal zone, these variations led to significant environmental changes, such as the invasion of Rhizophora mangroves into the Senegal River delta and along the river bed for several hundred kilometers upstream, including Lakes Rkiz (Grouard and Lézine, 2023) and Guiers (Lézine, 1988). While there is consensus on the identification of a transgressive period peaking around 5 ka, the “Nouakchottian” (Elouard, 1968), subsequent period is subject to more debate (Barusseau et al., 1995) due to fewer available dates. Nevertheless, Grouard and Lézine (2023) showed the retreat of the Rhizophora mangrove at Lake Rkiz between 4.2 and 2.1 ka, coinciding with marine regression identified further north in Mauritania, the “Tafolian” (Hébrard, 1978). Then, during the last millennium, a final, modest marine transgression led to the intrusion of saltwater into the bed of the Ferlo River, a tributary of the Senegal River, and the redevelopment of Rhizophora near Lake Rkiz (Faure et al., 1980; Fofana et al., 2020; Grouard and Lézine, 2023; Monteillet et al., 1981).

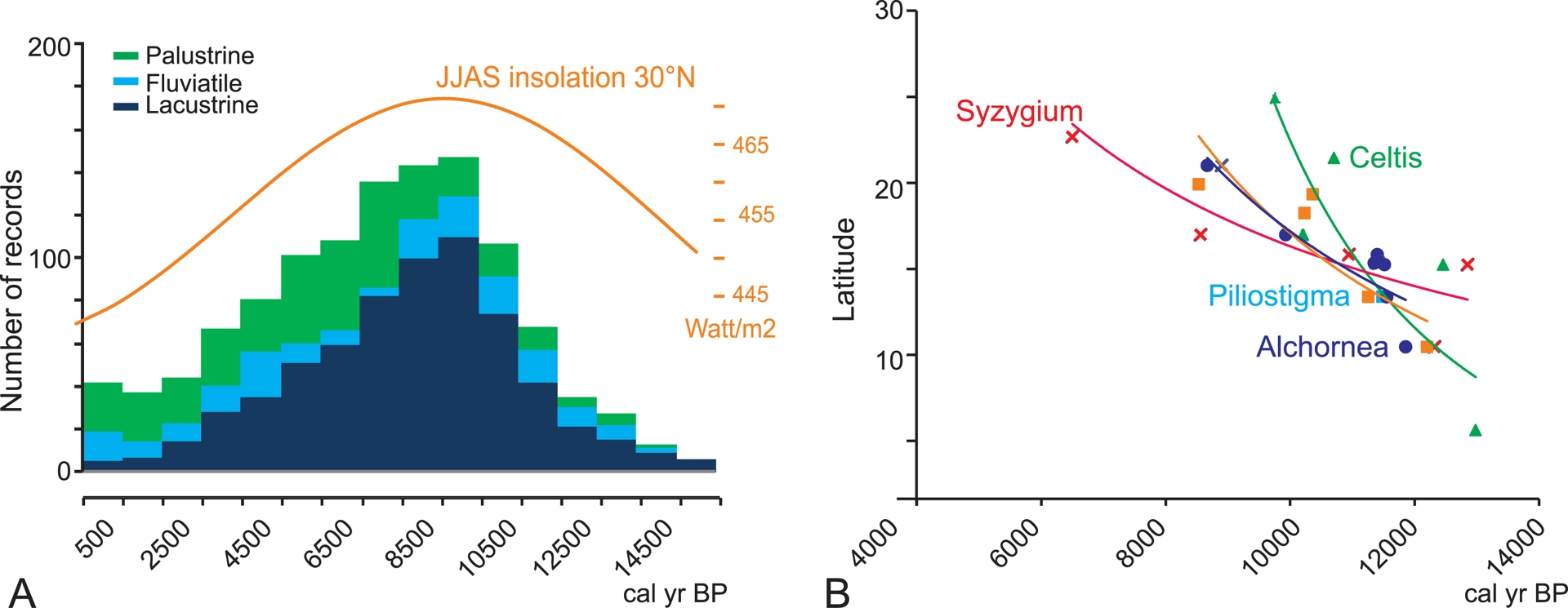

(A) African Humid Period derived from radiometric dating of four lake sediment categories from across Sahara and Sahel perennial (lacustrine) and seasonal (playas) lakes, rivers (fluviatile) and wetlands (palustrine). Insolation curve from Berger and Loutre (1991). (B) Northward migration of tropical trees across North Africa during AHP. Dots show the first appearance of selected tree pollen taxa (Celtis, Alchornea, Syzygium, Piliostigma) at the latitude of the studied sites (Lézine, 2017).

3.2. The African Humid Period (AHP)

The increase in summer insolation induced by orbital changes during the last glacial–interglacial transition enhanced a thermal contrast between land and sea, producing heavy summer monsoon rains that, in turn, formed numerous lakes in the current arid regions of Sahara and Sahel (COHMAP MEMBERS, 1988). Dated hydrological records from these regions show that the number of deep freshwater lakes gradually increased from as early as 15.5 ka, then accelerated from 12 ka to reach a maximum between 9.5 and 8.5 ka, in a phase with a summer insolation maximum (Berger and Loutre, 1991) (Figure 3). Then the number of lake records regularly decreased over time until present. From the mid-Holocene, the increase in palustrine (marsh/swamp) records, coupled with a gradual decrease in lake records, clearly confirms the progressive dryness in the region. In more detail, the drying up of the Saharan lakes occurred as early as the mid-Holocene, between 7.6 ka and 5.2 ka in Sudan (Ritchie, Eyles, et al., 1985; Ritchie and Haynes, 1987) or around 5.9 ka in Algeria (Lécuyer et al., 2016). In northern Chad, at Lake Yoa, the transition from a monsoon-dominated climate regime to one dominated by northern Mediterranean influences occurred around 4 ka, and present-day desert conditions were definitively established by 2.7 ka (Kröpelin et al., 2008; Lézine, Zheng, et al., 2011).

Vegetation responded to increased precipitation during the African Humid Period by migrating tropical plants northwards, up to the tropics (Hély et al., 2014; Watrin et al., 2009) (Figure 3B). These plants used lake and riverside wetlands as migration routes to enter the desert. Ritchie, Eyles, et al. (1985) and Ritchie and Haynes (1987) suggested that the southern limit of desert steppes was located 400 km north of its current position, around 16°N, while the northern limit of the Sudanian woodlands and wooded grasslands, currently at 14°N, shifted northwards to around 19°N during the period between 10 ka and 5 ka. Watrin et al. (2009) and Hély et al. (2014) have also shown that the distribution of vegetation in Sahara and Sahel during AHP was more complex than a simple displacement of vegetation zones. Plants now in distinct phytogeographical zones were capable of co-occurrence, with tropical trees (Sudanian to Guineo-Congolian) forming gallery forests near rivers and lakes, and Saharan steppic taxa on the surrounding dunes.

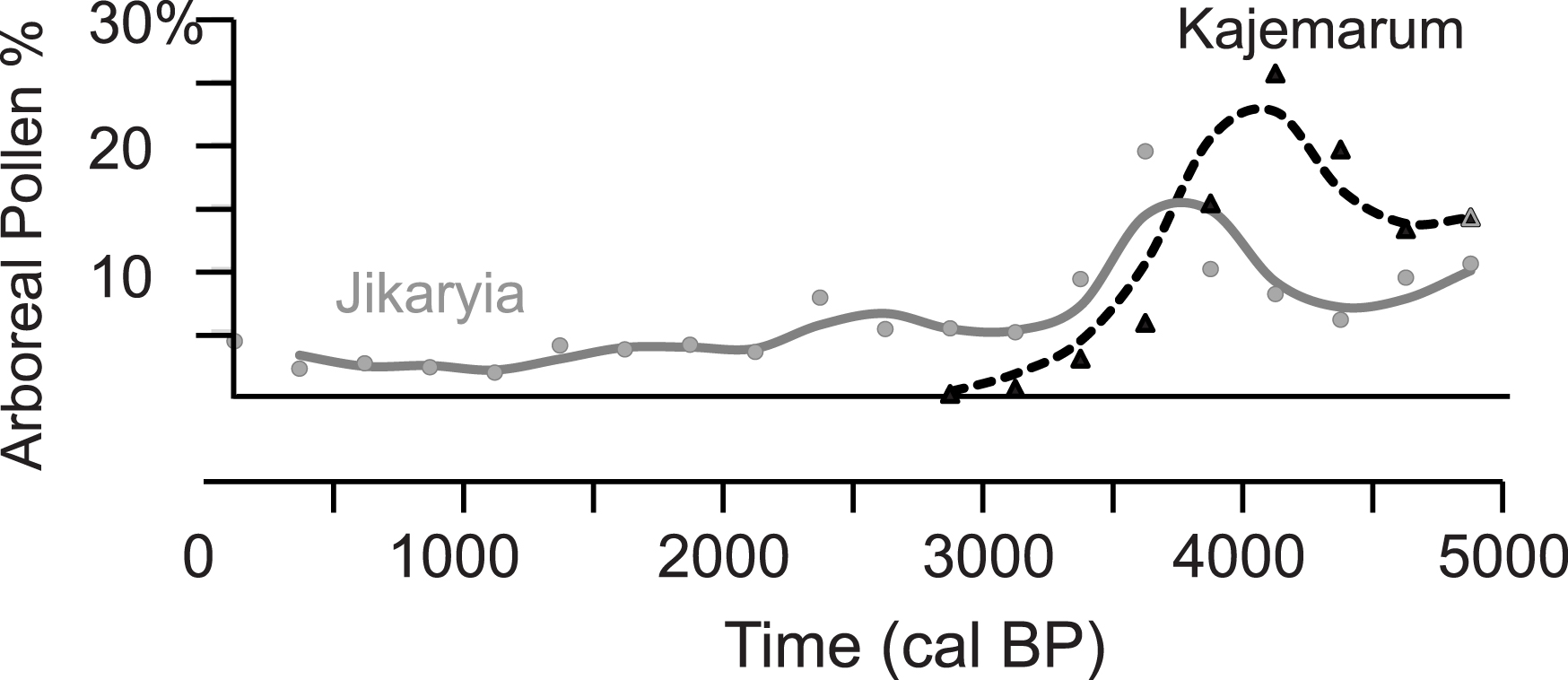

By the end of the AHP, the tropical trees retreated southwards. In the central Sahel, the forest cover, expressed as the total percentage of arboreal pollen in Figure 4, decreased dramatically from 4 ka onwards to its modern aspect. In the western Sahel (i.e., in the Niayes region), dense forest cover persisted for over about 2000 years due to the specific conditions of the Atlantic littoral (Lézine, Lemonnier, Waller et al., 2021).

Tree cover at the end of the AHP in the central Sahel. Kajemarum (Salzmann and Waller, 1998) and Jikaryiya (Waller et al., 2007) sites (northern Nigeria) show that trees (Arboreal Pollen %) fall from 4 ka onwards, more or less spectacularly depending on the site.

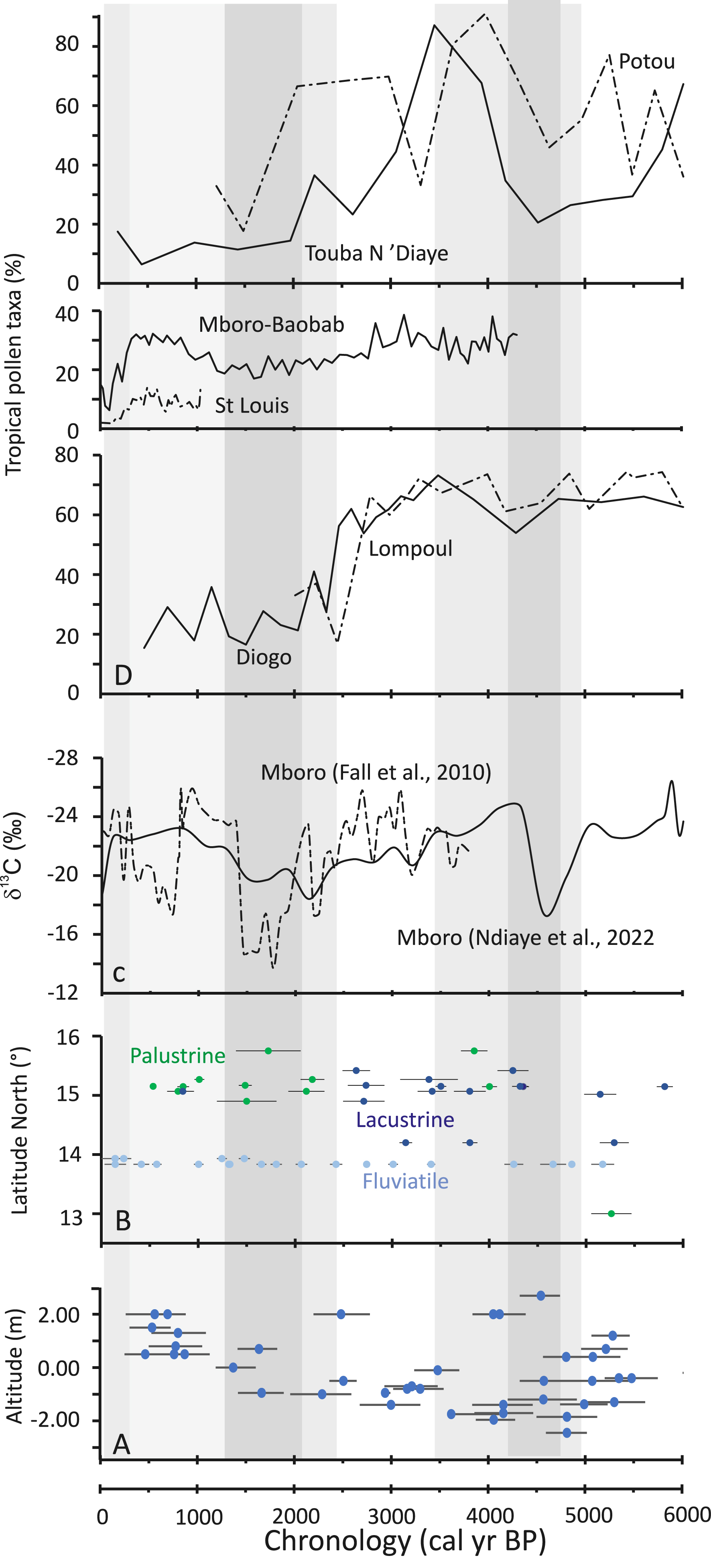

The end of the AHP in Senegal: (A) bleu dots: dated record of sea-level fluctuations as a function of altitude (Table 01); (B) dated hydrological records as a function of latitude (Table 02) (dark blue: lacustrine/high water level; green: palustrine/low water level; light blue: fluviatile); (C) isotopic geochemistry (δ13C) of bulk organic matter from two distinct Niaye depressions at Mboro (Fall et al., 2010; Ndiaye et al., 2022); (D) pollen records (in percentages) of tropical humid (sub-Guinean) taxa in western Senegal (Niayes region and Senegal River delta), from the bottom to the top: Diogo, Lompoul, Mboro-Baobab, St Louis, ToubaN’Diaye and Potou (Fofana et al., 2020; Lemonnier and Lézine, 2021; Lézine, 1988, https://africanpollendatabase.ipsl.fr). Grey bands indicate dry periods.

4. The data set

Sea-level variations are deduced from fossil shells and marine terraces (Faure et al., 1980). Of the 88 dated records, only 61 are associated with altitude (Figure 5A; Table 01). Hydrological records follow the methodology developed in Lézine, Hély, et al. (2011). We use 71 dated records of fluviatile, lacustrine (high water level), and palustrine (low water level) hydrological conditions from 12 localities in Senegal (Figure 5B; Table 02). These data were extracted from literature and field campaigns. Each sample was assigned to its specific category by considering the original interpretation of the authors and our own knowledge of tropical paleohydrology based on sedimentological (grain-size distribution), geochemical (13C data) and micropaleontological data: e.g., diatoms, aquatic pollen types (ibid.). Dating is based on accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) and conventional radiocarbon dates. Raw 14C dates were converted to calendar ages using CALIB 8.2 (Reimer et al., 2013). The reservoir age of 511 ± 176 years calculated for the sector of the West African coast closest to the site was applied to marine shells (Ndeye, 2008). Organic isotope records from Fall et al. (2010) and Ndiaye et al. (2022) are shown in Figure 5C. These records are expressed as δ13C, with less negative values (−14 to −16‰) indicating dry environmental conditions and grassland expansion, and the most negative values (−25, −27‰) indicating moist and forest expansion (Desjardins et al., 2020). Pollen percentages of tropical humid taxa (Guineo-Congolian to Sudanian) are shown in Figure 5D. As is usual in paleopalynology, they are calculated against a sum excluding aquatics and ferns. Age models used for both isotope and pollen records are those from the authors, except for Fall et al. (2010), for which it has been calculated using a linear interpolation between two dated levels, with the top of the sequence corresponding to zero.

5. Results

5.1. Paleohydrological changes

Hydrological records show that end of the AHP occurred in two successive drying phases (Figure 5B,D):

- An early drying event is recorded between 4.8 and 3.4 ka. At Mboro, Ndiaye et al. (2022) indicate that arid conditions set in around 4.8 ka, based on 13C data (Figure 5B,C). This arid phase continued until 3.8 ka in the Niayes region, as shown by the record of low water levels at Potou (Figure 5B). In addition, the absence of fluvial sediments in the Bao Bolon between 4.2 and 3.4 ka suggests that runoff ceased, confirming the setting of dry conditions (Figure 5B).

- After a return to wet conditions, a deep and widespread drought set in at 2.5 ka. All dated hydrological records from the Niayes region reveal a lowering of the water table (Figure 5B). This drought followed the gradual, though fluctuating, drying of hydrological conditions at Mboro from 4.3 ka onward (Figure 5C). These observations agree with previous data from Bouimetarhan et al. (2009), who showed the dramatic decrease of the Senegal River input starting from 2.5 ka then peaking at 2.2 ka.

Characterization of hydrological conditions during the last two millennia is more complex: Bouimetarhan et al. (ibid.) report periodic flash flood events in Senegal River after 2.2 ka, while Nizou et al. (2010) suggest a return to humid conditions between 1.0 and 0.7 ka. River flows in the Falémé and Bao Bolon ceased between 1.2 and 0.2 ka (Chevrier et al., 2016; Davidoux et al., 2018; Stern et al., 2019) (Figure 5B). A similar trend was recorded northward in the Senegal River Valley in St. Louis (Fofana et al., 2020) where dry conditions occurred at 0.2 ka. Dry conditions are also observed at Mboro in the Niayes region between 0.7 and 0.4 ka (Fall et al., 2010) (Figure 5C). Aridity was definitively established during the 19th century (Fofana et al., 2020; Lézine, Lemonnier and Fofana et al., 2019).

5.2. Forest evolution

Pollen data from the Niayes region show two different situations likely influenced by sites’ proximity to the water table (Figure 2). Diogo and Lompoul record a spectacular and continuous development of sub-Guinean gallery forests throughout the Holocene, with pollen taxa percentages equal to or exceeding 70% even after early Holocene forest optimum (Lézine, 1988). At both sites, gallery forests collapsed abruptly around 2.5 ka, with a dramatic loss of 35–50% of tropical forest taxa. At Touba N’Diaye and Potou, forest development was more variable. Sub-Guinean gallery forests were severely disturbed between 5.4 and 4.5 ka. Then they experienced a significant resurgence, peaking at 3.5 ka at Potou and 3.9 ka at Touba N’Diaye. This final period of forest development ended ca. 2.6 ka. A discrepancy between the two sites is likely due to the low resolution of data and the limited number of dates used to construct age models.

6. Discussion

6.1. The end of AHP in the Niayes region: a 2-stage process

The evolution of West Tropical African vegetation during the Holocene shows that, after the 9 ka forest optimum (Hély et al., 2014), Climate became more seasonal, allowing the development of Sudanian or Sudano-Guinean plants tolerant of a 5–7 month dry season at the expense of earlier, more humid forests. The first widespread forest disruption, however, was recorded later at 4.5 ka, corresponding to the strong disturbance or disappearance of gallery forest in Nigeria (Figure 4) and Chad (Kröpelin et al., 2008; Lézine, Zheng, et al., 2011; Salzmann and Waller, 1998; Waller et al., 2007). In Senegal, this event coincided with the opening up of Niayes landscape at Mboro, Potou, and Touba N’Diaye, as well as the cessation of Bao Bolon river activity. At Mboro, the landscape deteriorated to the point that gallery forests were replaced by grasslands (Ndiaye et al., 2022) (Figure 5C). At Potou and Touba N’Diaye however the forest strongly declined but never completely disappeared (Figure 5D). Unlike the central Sahel, this initial warning signal in the Niayes region was followed by a phase of forest redevelopment between 4 ka and 2.5 ka. However, local hydrology fluctuated greatly, with alternating wet and dry periods as the overall climate gradually dried, as shown by Mboro’s isotopic data (Fall et al., 2010; Ndiaye et al., 2022). Senegal River runoff was significant during the 2.9–2.5 ka (Bouimetarhan et al., 2009) or 2.75–1.9 ka interval (Nizou et al., 2010). The tipping point toward the end of the AHP was reached at 2.5 ka, with the collapse of many gallery forests and establishment of a grass-dominated landscape. After 2.5 ka, all dated hydrological records indicate the lowering of Niayes water bodies, with maximum drying between 2.1 ka and 1.4 ka. Yet, the Senegal River Basin experienced periodic flash floods (Bouimetarhan et al., 2009), and Bao Bolon and Falémé rivers continued flowing until 1.3 ka (Chevrier et al., 2016; Davidoux et al., 2018; Stern et al., 2019). This chronology of events agrees well with the sequence in northern Chad (Lézine, Zheng, et al., 2011), where monsoon influence declined around 4 ka, followed by the establishment of modern climatic conditions around 2.7 ka.

Over the last two millennia, gallery forests have not disappeared entirely from the Niayes region and Senegal River banks. They increased slightly between 1100–1680 CE Lemonnier and Lézine (2021), Ndiaye et al. (2022), due to favorable climate conditions as indicated by Senegal River freshwater discharge (Fofana et al., 2020) and reduced dust transport to the ocean (Mulitza et al., 2010). The present-day Niayes and Senegal River delta environment dates back 1850 CE (Lézine, Catrain, et al., 2023).

6.2. Have changes in seawater levels influenced groundwater levels in the Niayes and the development of gallery forests at the end of the AHP?

Configuration of piezometric level in the Niayes region (Figure 2) and proximity of the salt front may have significantly influenced forest cover heterogeneity and hydrological conditions revealed by palynological and geochemical analyses. Here, we attempt to assess their impact during the two dry events that marked the end of the African Humid Period.

The 4.5 ka dry event occurred during the “Nouakchottian” marine transgression, when sea-level was +3 m above present (Figure 5A). Contact between salt- and freshwater in the Niayes region had therefore shifted inland compared to today (Figure 1). This situation may have maintained humidity at the bottom of the interdunes, as the groundwater table lay above the saltwater table. This can be seen at Diogo and Lompoul, where dense gallery forests persisted despite arid climate. In contrast, the impact of the 4.5 ka dry event was more pronounced at Mboro-Baobab, Touba N’Diaye, and Potou, leading to a reduction in forest cover. This suggests these sites were located closer to the contact zone between salt and freshwater, and thus more sensitive to hydrological changes than previous sites. However, the situation in the Niayes was never as severe as in the central Sahel and Sahara, where tropical trees were definitively eliminated.

Between 4 ka and 2 ka, as sea-level generally declined, the Niayes environment underwent profound transformations directly linked to climate change: the phase of forest development and rising water table between 4 ka and 2.5 ka clearly indicates the establishment of humid conditions in the Niayes region. The filling of ponds at Sil and flu disruption of forests at 2.5 ka reflects activity of the Bao Bolon (Figure 5B) show this humid phase extended beyond the Niayes, into the Sudanian savannah zone (Lézine and Casanova, 1989). Conversely, widespread disruption of forests at 2.5 ka reflects the abrupt onset of arid conditions in the Niayes region. The retreat of the coastline and salt front likely amplified the impact of this drought episode on forest disturbance. By 2.5 ka, the Sudanian zone had returned to wetter conditions, as demonstrated by continuous fluvial records in the Bao Bolon.

7. Conclusion

Combined records from various sources for the period between 6 ka and 2 ka in Senegal reveal a nuanced picture of the end of the African Humid Period in the region. Rather than a single, abrupt shift from humid to arid conditions, the Niayes region experienced a two-phase transition. An initial drying event around 4.5 ka, marked by forest disruption, was followed by a period of fluctuating hydrology and forest regeneration. However, a tipping point occurred at 2.5 ka, leading to widespread forest collapse and the establishment of a grassland-dominated landscape. These two major phases demonstrate the non-linear response of continental systems to the gradual weakening of monsoonal fluxes over North Africa. This aligns with broader trends in the Sahel and the Sahara (Collins et al., 2017; Gasse et al., 1990), but it highlights the significant influence on local factors, particularly sea-level changes and their effect on groundwater, which modulated the regional drying trend. In this highly diverse area, due to its proximity to the shoreline and the subsequent influence of sea-level variations on groundwater levels, significant differences can be observed in the response of each interdunes depression to climate change. For instance, forest cover at Diogo and Lompoul sites exhibited an abrupt response at 2.5 ka, in contrast to the more gradual and/or highly variable response observed at the other Niayes sites. The heterogeneity of the vegetation response within this relatively small region underscores the complex interplay between climate, hydrology, and vegetation dynamics in this area during the end of the AHP. This emphasizes the importance of considering local hydrological conditions when reconstructing past climates and predicting future environmental changes.

Author contribution

MMY and AML designed the study and contributed to writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work contributes to ACCEDE ANR Belmont Forum project (18 BELM 0001 05) (France). MMY was funded by IRD and AML by CNRS in France. AML thanks the African Pollen Database for making pollen data stored and freely available.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Data availability

Pollen data are stored in the African Pollen database (https://africanpollendatabase.ipsl.fr). Other data used in this paper are available in the supplementary section or directly from the literature.

Underlying data

The underlying data for this article is available at https://doi.org/10.23708/RPBPQH.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0