Version française abrégée

1 Cadre géologique de l'étude

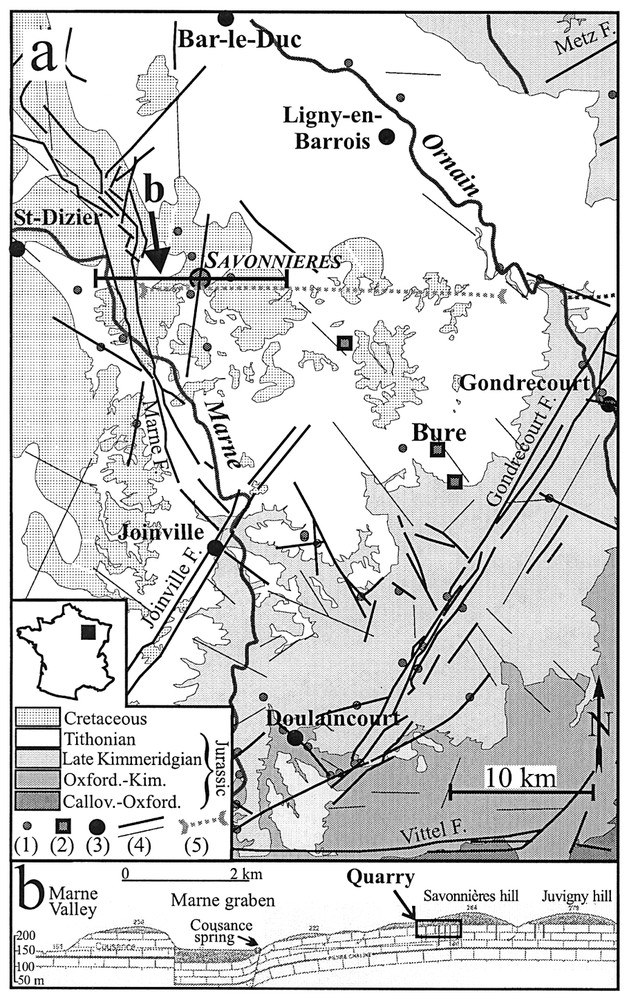

La carrière souterraine de Savonnières est située en Lorraine dans les formations du Jurassique supérieur de l'Est du Bassin parisien (Fig. 1), dans un synclinal mineur d'axe est–ouest principalement attribué à l'orogenèse pyrénéenne [3,9,19,27]. Elle se trouve à 20 m de profondeur dans les calcaires oolithiques du Jurassique terminal, sous les sables et argiles du Crétacé. Des karsts sous couverture se sont formés à l'interface Jurassique–Crétacé [13] lors de l'incision de la Marne, entre le Pléistocène moyen et le début du Quaternaire [13].

(a) Structural sketch map of the studied area (after [23], modified). 1: tectonic sites of palaeostress reconstructions, 2: ANDRA wells of Bure, 3: town, 4: fault, 5: syncline axis. Black thick line: cross-section. (b) East–west trending geological cross-section going though Savonnières and the Marne Trench.

(a) Carte structurale schématique de la région de Savonnières ([23], modifié). 1: sites d'analyse tectonique; 2: forages de Bure (Andra); 3: ville; 4: faille, 5: synclinal. Ligne noire épaisse: coupe. (b) Coupe géologique est–ouest passant par Savonnières.

2 Paléocontraintes régionales

Dans cette région, l'inversion d'un millier de mesures de stries de failles par la méthode d'Angelier [1,2] a permis d'établir l'histoire tectonique suivante [21], compatible avec celle reconnue dans la plate-forme européenne [3,11,18,27] : (1) extensions précoces orientées NE–SW et est–ouest (ouverture de l'océan Téthys) ; (2) états de contraintes décrochants majeurs, avec σ1 orienté NW–SE, puis NE–SW (orogenèse pyrénéenne) ; (3) extension WNW (Oligocène) ; (4) transpression ENE au Miocène inférieur [3], puis WNW au Miocène terminal–Pliocène (phase alpine majeure). L'état de contraintes régional actuel est suggéré par l'ouverture de fractures orientées NW–SE [12,21], tapissées de calcite, et à l'échelle de l'Est de France, par les mécanismes au foyer des séismes [8].

3 Observations dans la carrière souterraine de Savonnières

3.1 Observations à l'échelle macroscopique

Dans la carrière, la succession régionale est partiellement reconstituée par l'analyse des plans striés : (1) extension environ est–ouest au Jurassique supérieur avec des failles normales N000-030 ; (2) compression pyrénéenne NW–SE réactivant ces failles en décrochements sénestres ; (3) extension oligocène mineure réactivant ces failles (stries normales ténues).

Les fractures NNE de cette carrière sont ouvertes et karsifiées [12,21]. Un conduit karstique vertical orienté nord–sud présente une jonction sectionnée et légèrement décalée en faille normale.

3.2 Observations à l'échelle microscopique

Trois échantillons S1, S2 et S3, espacés de quelques dizaines de centimètres, ont été extraits d'un plan de faille N035° karstifié, recouvert par une cristallisation de calcite d'épaisseur centimétrique, datée de moins de 200 ka (U/Th) [13].

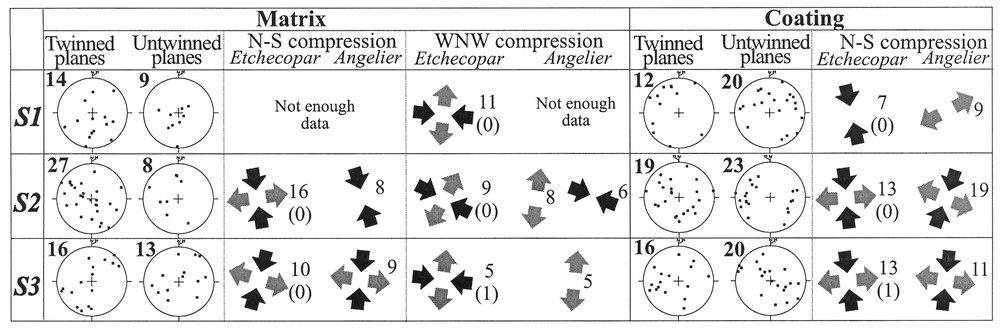

Dans ce placage, les cristaux de calcite sont sparitiques et purs. Dans les rares cristaux maclés (Fig. 2), le maclage s'est produit sur une seule des trois directions potentielles de maclage ; les macles sont rectilignes, très fines et uniques dans chaque direction maclée. Des microfractures orientées N000–030° sont ouvertes entre les cristaux (Fig. 2).

Photographs. (a) Mechanical e twins in the calcite coating. Twins are ultra-thin and not curved (low strain at low temperature); open fractures formed between the crystals, trending N000-030°. (b) Mechanical twin sets in the calcite of the rock matrix.

Photographies. (a) Macles mécaniques e dans le placage de calcite, ultra-fines et rectilignes (déformation faible à basse température); fractures ouvertes entre les cristaux, orientées N000-030°. (b) Macles mécaniques dans la matrice de la roche.

La roche encaissante contient de la calcite micritique renfermant de nombreuses inclusions (Fig. 2). Dans les cristaux les plus gros (100 μm), des macles multiples se sont formées sur une à trois des directions potentielles.

4 Reconstitution des paléocontraintes par diverses méthodes

À basse température et à basse pression, les agrégats de calcite se déforment préférentiellement par maclage mécanique le long des plans cristallographiques , appelés plans e (trois par cristal [26], Fig. 2). Le maclage ne se produit sur ces plans que si la contrainte cisaillante résolue sur chaque e excède le seuil de maclage [24].

Les tenseurs des contraintes ont été calculés à partir des plans maclés et non maclés par la méthode d'inversion d'Etchecopar [6], validée dans des régions variées à couverture carbonatée peu déformée [16,17,20,21,24]. En théorie, la valeur de la contrainte cisaillante résolue doit être plus grande pour tous les plans maclés compatibles avec le tenseur-solution que pour tous les plans non maclés. L'inversion des données fournit l'orientation des axes principaux des contraintes et σ3 (compression positive, σ1⩾σ2⩾σ3) [5,25], le rapport Φ des contraintes différentielles , et la valeur de σ1−σ3 [6,15,17,24].

En raison de la rareté du maclage, le nombre de mesures est égal au tiers de celui auquel on a habituellement recours pour des reconstructions de paléocontraintes [16,20]. La marge d'erreur atteint ±15° sur la direction des axes, ±0,2 pour Φ, et est disproportionnée pour la valeur de σ1−σ3. Une méthode indépendante, conçue pour la reconstruction de contraintes à partir des stries de failles [1,2,4,7], a été appliquée sur les plans maclés. L'interprétation mécanique des macles comme des plans de faille microscopiques ne prend pas en compte l'existence d'une strie prédéterminée et du seuil de maclage. L'application des méthodes inverses d'Angelier [1,2] n'a donc été réalisée que pour vérifier les résultats en termes d'orientation des axes et σ3.

4.1 Résultats des inversions

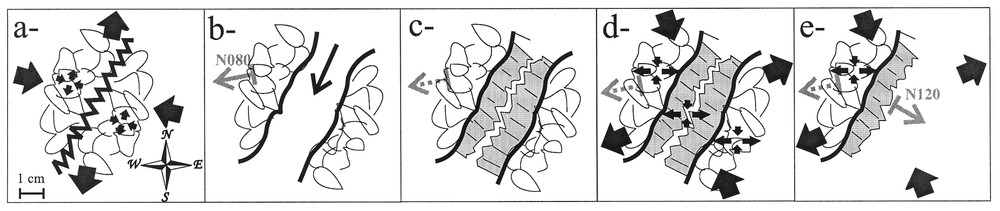

Dans les trois échantillons, quelle que soit la méthode inverse appliquée, la calcite de la matrice de la roche a enregistré un état de contrainte de plus que la calcite en placage (Fig. 3). Dans la matrice, la calcite a subi (1) un régime décrochant, avec σ1 WNW et/ou σ3 NNE, appelé « compression WNW » par la suite, et (2) un régime décrochant avec σ1 nord–sud et/ou σ3 est–ouest, appelé « compression nord–sud » par la suite. Dans le placage de calcite, seule la compression nord–sud est reconstituée.

Distribution of poles to measured twinned and untwinned planes (with number) in the calcite coating and in the calcite of the rock matrix for the three samples S1, S2 and S3 of Savonnières quarry (lower hemisphere, equal area projection); stress tensors determined by inverse analysis of calcite twins, using the methods of Etchecopar [6] (twinned and untwinned planes) and Angelier [1,2] (twinned planes). For each tensor, the number of consistent twinned planes is indicated. For the Etchecopar's method, the number of inconsistent untwinned planes is in brackets. Centripetal arrows: compression (σ1); centrifugal arrows: extension (σ3).

Distribution des pôles des plans maclés et non maclés mesurés (avec nombre) dans les échantillons de la carrière de Savonnières prélevés dans un placage de calcite (coating), et dans la matrice de la roche (matrix); paléocontraintes reconstituées par les méthodes d'Etchecopar [6] (plans maclés+non maclés) et d'Angelier [1,2] (plans maclés). Pour chaque tenseur est indiqué le nombre de plans maclés compatibles, et, entre parenthèse pour la méthode d'Etchecopar, le nombre de plans non maclés incompatibles. Flèches centrifuges: extension (σ3); flèches centripètes: compression (σ1).

5 Interprétations possibles

Le caractère ténu des deux états de contraintes précités explique le fait qu'ils n'ont pas été reconstitués par l'analyse des failles ; la calcite est connue pour être plus sensible aux faibles contraintes [20].

La compression WNW (Fig. 4) reconstituée dans la matrice est attribuable à la compression alpine du Miocène terminal–Pliocène [3,21].

Evolution of the sampled fracture plane, shown in horizontal plane. Local phenomena: grey arrows. Regional stresses: large black arrows. Stresses recorded by the calcite: small black arrows. (a) Calcite crystallization in the rock matrix and recording of the Mio-Pliocene WNW compression. (b) Incision of the Marne river valley cleaning out the walls (karst) and possibly inducing N080° tensional stress. (c) Calcite crystallization of the coating (less than 200 ka [13]). (d) Recording of the north–south compression both in the calcite coating and matrix (Quaternary). (e) Quarry excavation and possible N120° tensional stress.

Évolution du plan de fracture échantillonné, représenté dans le plan horizontal. Phénomènes locaux: flèches grises. Contraintes régionales: grosses flèches noires. Contraintes enregistrées par la calcite: petites flèches noires. (a) Cristallisation de la calcite dans la matrice de la roche et enregistrement de la compression WNW mio-pliocène. (b) Incision de la vallée de la Marne entraı̂nant lessivage des parois (karst) et extension N080°. (c) Cristallisation du placage de calcite (moins de 200 ka [13]). (d) Enregistrement de la compression nord–sud dans le placage et la matrice (Quaternaire). (e) Excavation de la carrière (étirement N120°).

La compression nord–sud, unique état de contraintes enregistré dans le placage, date donc du Quaternaire. Elle peut correspondre à un épisode tectonique régional, à un état de contraintes local, ou encore à un épisode tectonique régional, modifié par des phénomènes locaux.

Le champ de contraintes actuel reconnu dans cette région est décrochant avec σ1 orienté NNW [8], comme l'illustre l'ovalisation des forages de Bure (laboratoire souterrain de l'Andra), situés à 10 km au sud–est (Fig. 1) [10]. Divers états de contraintes locaux peuvent être envisagés.

- 1. L'incision de la vallée de la Marne, située à 4 km à l'ouest de la carrière, a pu engendrer un relâchement des contraintes dans la direction N080° (perpendiculaire à la faille de la Marne, Figs. 1 et 4). La carrière, située dans une colline, est susceptible d'avoir subi d'autres contraintes d'origine topographique [22].

- 2. La compression nord–sud n'a pu être enregistrée qu'avant l'excavation, lorsque les épontes de la faille étaient jointives. L'excavation de la carrière a cependant pu induire un étirement N120° (perpendiculaire au mur ; Fig. 4), qui expliquerait les microfractures observées entre les cristaux (Fig. 2).

- 3. La carrière étant dans un synclinal d'axe est–ouest, les contraintes ont pu être accrues dans la direction nord–sud si le pli a été réactivé (effet compressif d'intrados).

Tous ces phénomènes ne peuvent pas expliquer le caractère décrochant de l'état de contrainte reconstitué dans le placage de calcite, qui ne peut être attribué qu'à la tectonique régionale. La compression nord–sud, responsable essentiel des déformations observées dans la carrière sur le réseau karstique, est donc représentative du champ de contrainte régional quaternaire, certes modifié par des phénomènes locaux (Fig. 4) en termes d'orientation des axes et de valeur des contraintes.

6 Conclusions et perspectives

D'un point de vue méthodologique, cette étude montre que la méthode d'Etchecopar permet de reconstituer les directions des contraintes, même sur un faible nombre de données ; les résultats ont été vérifiés à l'aide de la méthode d'Angelier appliquée à l'analyse des plans maclés.

D'un point de vue tectonique, l'analyse du maclage de la calcite permet de déterminer des états de contraintes récents à actuels [14]. Une modélisation numérique est envisagée pour quantifier l'effet des phénomènes locaux sur le champ des contraintes régional. D'autres mesures sont nécessaires dans la carrière pour déterminer les valeurs des contraintes actuelles, puis à l'échelle de la région pour en déterminer la variation spatiale.

1 Geological setting

The study area is located in Lorraine (eastern France) in the Upper Jurassic formations of the East of the Paris basin. This area (Fig. 1) is bounded to the north by the Metz fault, to the south by the Vittel fault, to the west by the Marne faults and to the east by the Gondrecourt faults.

The disused underground quarry of Savonnières is situated in a long-wave syncline with east–west-trending axis mainly attributed to the Pyrenean collision phase [3,9,19,27]. It is located 20 m deep in the Tithonian oolitic limestones, gently dipping to the west, just beneath the sands and mudstones formations of the Cretaceous. Undercover karsts have formed at the Jurassic–Cretaceous interface [13], from the Middle Pleistocene to the Early Quaternary [13] during the incision of the Marne River.

2 Regional palaeostresses

In this area, nearly 1000 fault striae have been measured and analysed through the inverse method of Angelier [1,2]. The following tectonic succession deduced from these analyses [21] is consistent with the one recognised in the European platform [3,11,18,27]: (1) early extensions trending NE–SW and east–west, poorly represented in the regional measurements, attributed to the Tethys rifting; (2) a succession of major states of stress, probably due to the Pyrenean orogeny, corresponding in most cases to strike slip regimes, with σ1 trending NW–SE then NE–SW; (3) an extension trending WNW, probably Oligocene in age; (4) finally, a succession of transpressions, the first one trending nearly ENE being minor and dated as Early Miocene [3], then the second one trending nearly WNW being attributed to the Late Mio-Pliocene phase of alpine orogeny. The focal mechanisms of earthquakes [8] in Eastern France indicate a present-day NNW-trending transpression, consistent with the local in situ stress measurements and with the observed opening and calcite crystallisation along numerous NW–SE trending fractures overall this area [12,21].

3 Observations in the Savonnières underground quarry

3.1 Observations at the macroscopic scale

This regional tectonic succession is partly reconstructed in the quarry by fault slip analyses: (1) an east–west-trending extension, attributed to the Late Jurassic, has induced normal faults trending N000-030; (2) a NW–SE-trending compression, corresponding to the early Pyrenean compression, has reactivated these faults with a left-lateral strike-slip motion; (3) the Oligocene extension is represented by minor normal striae on previous faults.

In the quarry, only the NNE-trending fractures are open and karstified [12,21]. A bridge linking the two sides of a vertical conduit trending north–south is broken, with an opening and a vertical offset of nearly 10 cm (normal faulting).

3.2 Observations at the microscopic scale

Three oriented samples S1, S2 and S3 spaced of few tens centimetres were extracted from the wall of a N035°-trending karstified fault plane covered by a centimetre thick calcite. The calcite coating post-dates the karst [13] and is dated (U/Th) at less than 200 ka [13]. The second wall of the crystallised fracture has been removed during the excavation.

In this calcite coating, the crystals are sparitic, pure, and seldom twinned (Fig. 2); optical axes are randomly spaced. In the few twinned crystals, twinning occurred in only one of the three directions of potential twinning. Twins are straight and generally unique in each twinned direction. Open fractures trending N000-030° occurred between the crystals (Fig. 2).

In the matrix, the calcite is micritic with numerous inclusions. Twinning occurred in one to three directions, and several times in each twinned direction (Fig. 2).

In each sample, measurements were made in three perpendicular thin sections, separately in the calcite matrix and in the coating. For the calcite coating, the data were collected in the twinned crystals. For the matrix, measurements were made in the largest crystals (100 μm).

4 Stress reconstructions with various methods

4.1 Calcite twin data inverse methods

At low pressure and temperature conditions, calcite aggregates deform primarily by mechanical twinning along crystallographic planes named the e-twin planes (three per crystal [26], Fig. 2). Twinning occurs along an e plane only if the resolved shear stress acting on it equals or exceeds the yield stress value for twinning [24].

The palaeostress tensors were determined from twinned and untwinned data through the numerical inverse method of Etchecopar [6], a technique that has been validated in various regions of unmetamorphosed and weakly deformed carbonate cover rocks [16,17,20,21,24]. Theoretically, the value of the resolved shear stress must be larger for all the twinned planes consistent with the tensor solution than for the untwinned planes. Data inversion provides the orientation of principal stress axes , and σ3 (positive compression, σ1⩾σ2⩾σ3) related to calcite twinning [5,25], the Φ ratio of the differential stress values and the maximum differential stress σ1−σ3 [6,15,17,24].

Because twins were not numerous, the number of measurement is the third of the one generally used for palaeostress reconstructions [16,20]. The number of measured untwinned planes is clearly insufficient in the matrix of samples S1 and S2 (Fig. 3). The error margin reaches ±15° on trends of stress axes, ±0,2 on Φ, and is disproportionate for σ1−σ3 value. An independent method, generally used for stress reconstruction with slip of minor faults [1,2,4,7], was applied on the twinned plane data. The difference between faulting and twinning is that twinning occurs in a sole trend and direction of slip, above a fixed yield stress. Thus, the interpretation of mechanical twins as microscopic fault slips induces an important error margin on the evaluated stress trends and removes the information about the stress magnitudes. The computerised methods of Angelier [1,2] were thus applied with the sole aim at verifying the obtained results in terms of orientation of , and σ3 stress axes.

4.2 Results of inversions

In the three samples and with both methods, the inversions reveal an additional state of stress in the matrix compared to the coating (Fig. 3). In the matrix, calcite has undergone (1) a strike-slip regime with σ1 trending WNW an/or σ3 trending NNE, called ‘WNW compression’ below, and (2) a strike-slip regime with σ1 trending north–south, called ‘north–south compression’ below. In the calcite coating, only the north–south compression is reconstructed.

5 Possible interpretations

These two states of stress were probably not important enough to induce faulting; the calcite is known to be a sensitive marker of weak stress [20].

The WNW compression reconstructed in the rock matrix (Fig. 4) can be attributed to the regional Late Miocene to Pliocene alpine compression [3,21].

The north–south compression, unique state of stress recorded by the calcite coating, thus occurred at the Quaternary, and corresponds to the last local state of stress important enough to induce calcite twinning. It may correspond to a regional post-Pliocene tectonic event, or to a local state of stress, or to regional post-Pliocene tectonic event modified by local phenomena.

The regional Quaternary stress field corresponds to a strike-slip regime, with σ1 trending NNW [8], as illustrated by the borehole breakouts of Bure (ANDRA's underground laboratory), situated 10 km to the southeast (Fig. 1) [10]. Some local stresses can be invoked.

- 1. The incision of the Marne River valley, 4 km west of the quarry, could have created an attracting gap, thus a nearly N080° stretching (perpendicular to the Marne fault scarp; Figs. 1 and 4). Even if the incision of the Marne River valley occurred before calcite coating crystallisation (Fig. 4), the stretching could have continued for a long time. The position of the quarry under a hill has probably influenced the local stress field [22].

- 2. The north–south compression has necessarily been recorded when the two walls of the fault were jointed, before the excavation (Fig. 4). However, the tensile stress induced by the quarry excavation (perpendicularly to the fault plane, i.e., N120°, Fig. 4) could explain the microfractures observed between the crystals (Fig. 2).

- 3. Finally, the quarry is located in an east–west-trending syncline (Fig. 1); even a weak fold reactivation could have increased the stresses in the north–south direction in the heart of the syncline.

However, the local stress mentioned above cannot explain the strike-slip regime of the reconstructed state of stress, which can only be explained by a regional tectonic stress field. The reconstructed north–south compression thus reflects the regional Quaternary stress field more or less modified by local phenomena in terms of stress trends and values. This state of stress is consistent with the deformations observed on the karst network in the quarry.

6 Conclusions and future work

From the methodological point of view, this study shows that the Etchecopar's method [6] is reliable to reconstruct the directions of stress tensors and Φ ratio, even with small amount of data. The Angelier's method [1,2] applied on calcite twin planes brought confirmation that valid results had been obtained.

This study brings significant information concerning the use of calcite twinning as a way to determine Recent to Present-day states of stress [14]. A numerical modelling is proposed in order to quantify the effect of the local phenomena on the tectonic stress field. Other Quaternary deposits need to be sampled in this quarry in order to evaluate the differential stress values, and in other sites of this area in order to determine the space variability of the stress tensor.

Acknowledgements

Comments by J. Angelier and A. Etchecopar resulted in significant improvement of the paper. The authors thank J.-P. Villotte and to C. Demeurie for the making of the thin sections, and COGEMA and the ‘Laboratoire de tectonique’ of University Pierre-et-Marie-Curie (Paris-6) for the use of the Universal stage and the microscope.