Version française abrégée

1 Introduction, contexte sismotectonique

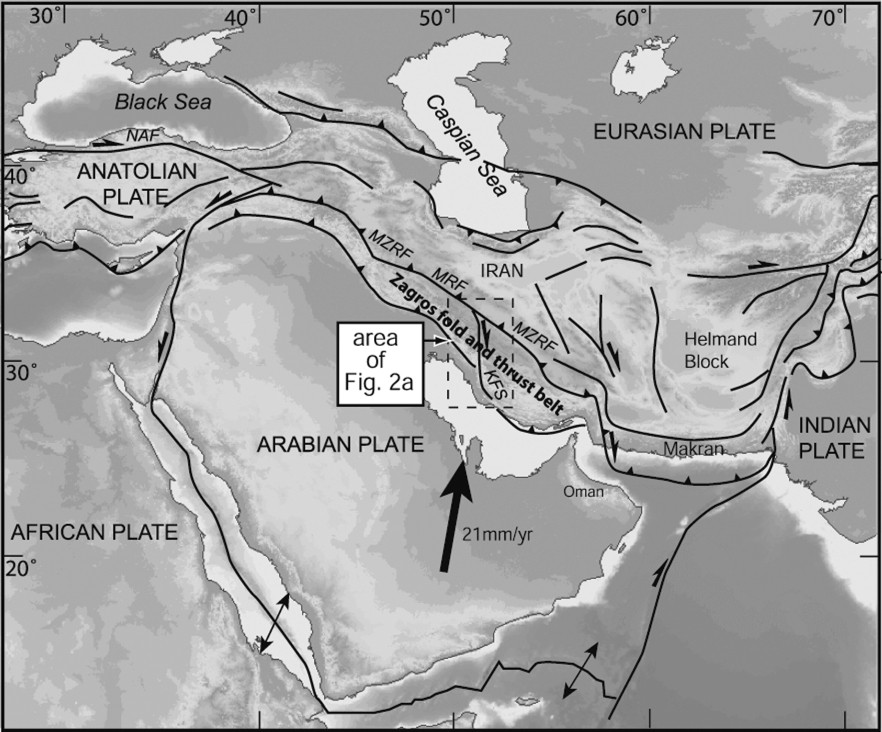

La ceinture de chevauchement du Zagros est une jeune chaîne de collision oblique. Cette chaîne résulte de la collision néogène entre l'Arabie et l'Eurasie [12] (Fig. 1), qui convergent aujourd'hui selon une direction NNE à une vitesse de (méridien 50°E), impliquant un taux de raccourcissement à travers le Zagros de l'ordre de [16]. La Main Recent Fault (MRF) est un décrochement dextre majeur, qui suit et recoupe le chevauchant marquant la limite arrière de la chaîne (backstop), la Main Zagros Reverse Fault (MZRF) [12]. Le système de failles de Kazerun (KFS) appartient à une série de failles de direction NNE, héritées d'une phase tectonique néoprotérozoïque et dont la sismicité et la signature morphologique indiquent qu'elles sont actives et affectent le socle du Zagros (Fig. 2a) [4,5]. Le KFS s'étend de la terminaison orientale de la MRF, au nord, au golfe Persique, au sud. Il marque la limite entre deux domaines sismotectoniques contrastés (largeur de chaîne différente de part et d'autre, sismicité distribuée à l'est et localisée à l'ouest, prédominance de dômes de sel à l'est de la faille [7,13,15]). Nous présentons ici les résultats d'une analyse tectonique du KFS et de la MRF. Ils permettent d'envisager que le mouvement décrochant, enregistré à l'arrière de la chaîne par la MRF et issu du partitionnement de la convergence oblique, est transféré vers l'intérieur de la chaîne par l'intermédiaire du KFS.

Structural frame of the Middle-East portion of the Alpine collision belt [5]. NAF, North Anatolian fault; MZRF, Main Zagros Reverse Fault; MRF, Main Recent Fault; KFS, Kazerun fault system.

Schéma structural de la collision Alpine au Moyen-Orient [5]. NAF, faille nord-anatolienne ; MZRF, Main Zagros Reverse Fault ; MRF, Main Recent Fault ; KFS, système de faille de Kazerun.

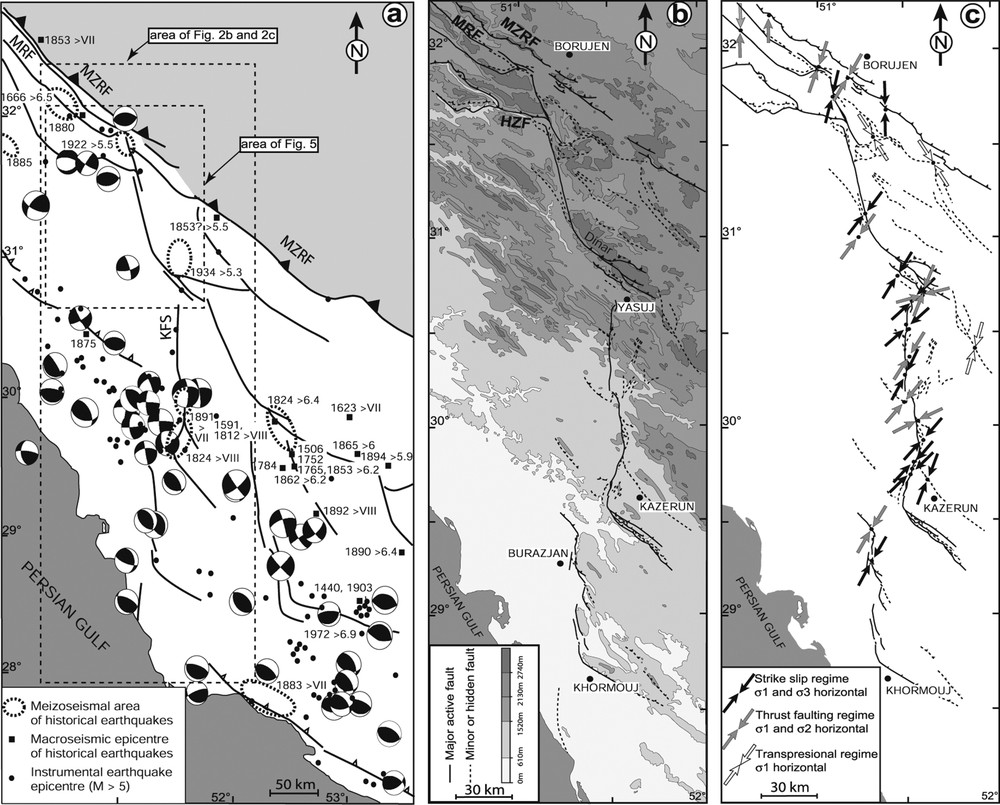

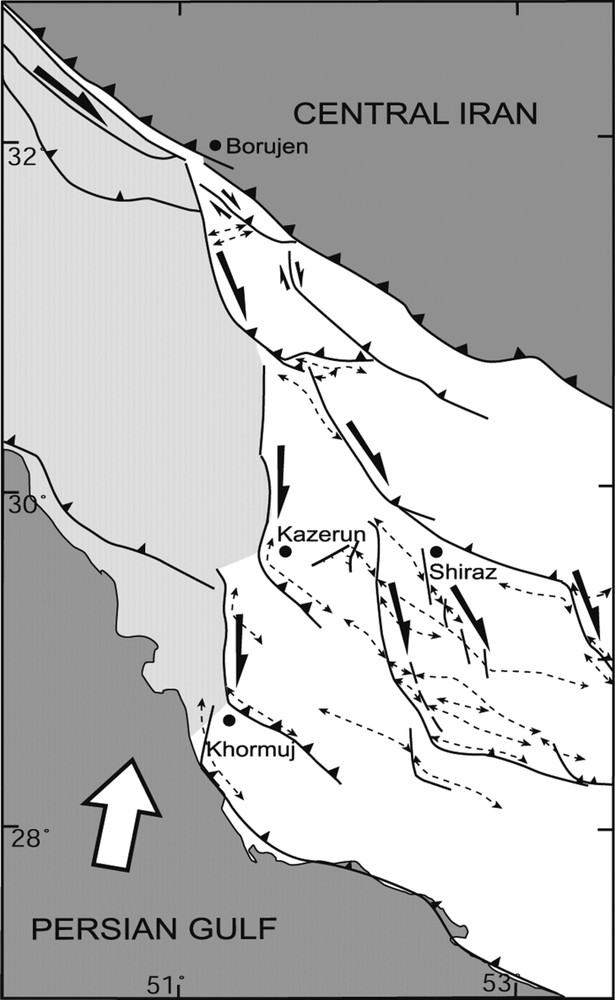

(a) Compilation of shallow (⩽60 km) earthquake epicenters and focal mechanisms in the Zagros fold-and-thrust belt superimposed on a fault pattern (located in Fig. 1). (b) Active fault segmentation of the KFS. (c) Results of the fault-slip data inversion (using the method originally proposed by Carey [8]). Arrows represent axis strikes. Fig. 2b and c are located in Fig. 2a.

(a) Compilation des épicentres superficiels et des mécanismes au foyer dans la chaîne du Zagros au voisinage du système de faille de Kazerun et (b) trace de sa segmentation active. (c) Résultats des inversions de populations de failles (selon la méthode initialement proposée par Carey [8]). Les flèches représentent l'axe . Localisation de la Fig. 2b et c sur la Fig. 2a.

2 Résultats

Le KFS est composé de trois zones de failles de longueur équivalente () et de direction nord–sud. Leur terminaison méridionale en queue de cheval est courbée selon une direction sud-est (Fig. 2b) et passe latéralement à des rampes chevauchantes parallèles à la chaîne. La zone nord du KFS est connectée à la terminaison orientale de la MRF par l'intermédiaire d'une discontinuité étroite en zone de relais courbe (Fig. 2b). La zone sud du KFS, constituée de segments en échelon, décale de 100 km vers le sud le front occidental de la ceinture de chevauchement. La prolongation méridionale du KFS est suggérée par la distorsion de l'anticlinal côtier (Fig. 2b).

L'étude cinématique des failles sur 28 sites le long du KFS (Fig. 2c) permet de contraindre le régime tectonique du KFS et l'état de contraintes associé (méthode Carey [8]). Elle indique un régime homogène décrochant ( vertical) dextre tout le long du KFS et un régime chevauchant ( vertical) sur les terminaisons longitudinales. Comme les mécanismes aux foyers, ces résultats correspondent à un régime de contraintes (Fig. 2a), où la direction de est perpendiculaire à la direction générale des structures du Zagros (Fig. 3b).

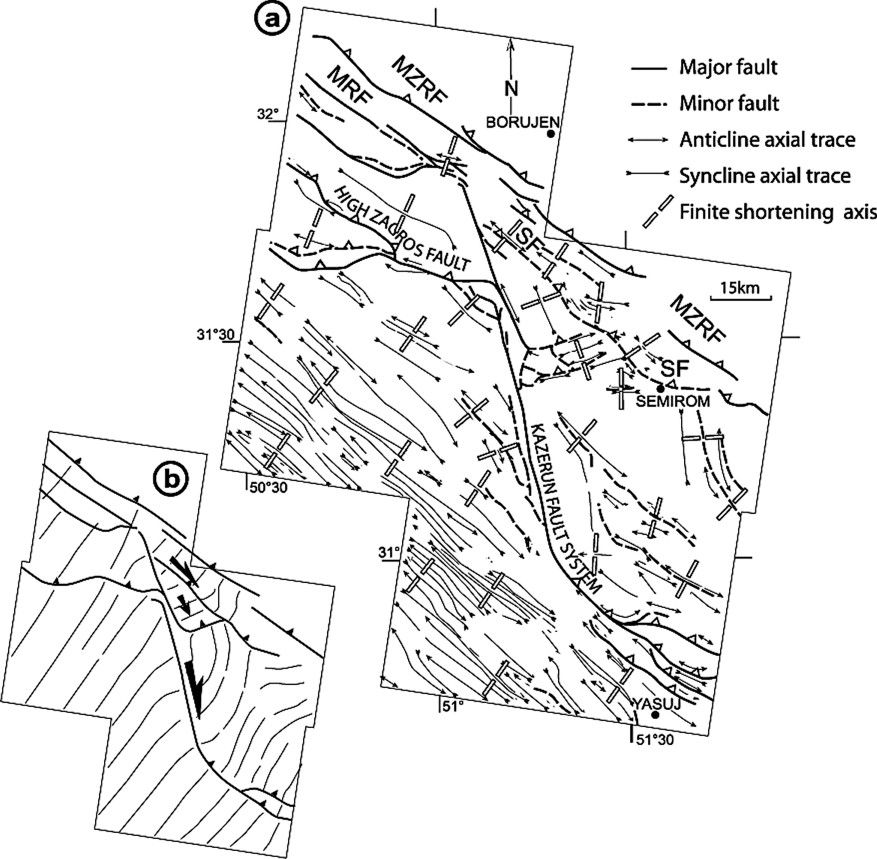

(a) Structural map of the Borujen region. (b) Shortening trajectories (normal to the fold axes) superimposed on the main structures.

(a) Schéma structural de la région de Borujen. (b) Trajectoires de raccourcissement (normales aux axes de plis) superposées aux structures principales.

Afin de déterminer les relations entre le KFS, la MRF et la MZRF, une analyse structurale a été réalisée autour de la zone nord du KFS (Fig. 3). La MZRF, non active [6], marque la limite septentrionale de la région étudiée. Au sud-est de sa terminaison, la MRF fait place au KFS et à la faille transpressive de Semirom. Cette dernière appartient au bloc en forme de coin limité à l'ouest par le KFS et au nord par la MZRF. Ce compartiment montre des trajectoires de raccourcissement apparemment hétérogènes, mais compatibles avec l'interférence des jeux des failles décrochantes et chevauchantes contenues dans le bloc (Fig. 3b).

3 Discussion

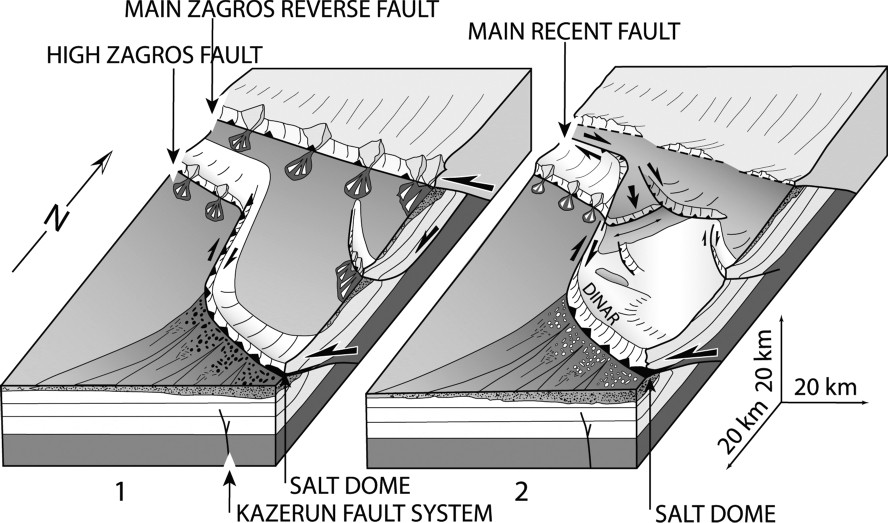

Les figures d'interférence reconnues à l'extrémité nord du KFS sont interprétées comme résultant d'une évolution de cette région en deux stades, sur la base de nos propres observations structurales et des données de la littérature (Fig. 4). Le premier stade correspond à un mouvement essentiellement en faille inverse du KFS, permettant l'exhumation de formations jurassiques à l'est de la faille, alors qu'elles sont connues à une profondeur de l'ordre de 5 km à l'ouest de celle-ci [11]. Ce mouvement débute à la fin du Crétacé, période où la zone de faille nord du KFS formait le front de la chaîne du Zagros [6]. Lors de la deuxième phase, la MRF se connecte au KFS, qui acquiert le régime décrochant dextre caractérisé ici. Le début du deuxième stade correspond à l'activation de la MRF, indirectement datée du Pliocène inférieur [9,14]. Cette faille recoupe le MZRF, qui, dès lors, n'est plus actif [9]. Le transfert partiel du mouvement de la MRF vers l'intérieur du bloc en coin est la conséquence de l'activation de la zone de relais courbe entre la MRF et le KFS et produit les figures d'interférence décrites plus haut. Le mouvement inverse sur le KFS se trouve alors transféré sur la terminaison méridionale de la zone de faille nord du KFS (chevauchement du Dinar, Fig. 4).

Block diagrams showing the two-stage evolution model of the northern termination of the Kazerun fault system.

Bloc diagrammes de l'évolution en deux stades de la terminaison nord du système de faille de Kazerun.

Le schéma cinématique développé lors de la deuxième phase de déformation peut être étendu à l'échelle du Zagros (Fig. 5). En effet, le mouvement le long de la MRF est distribué sur un réseau de failles en éventail, limité à l'ouest par le KFS, qui recoupe toute la largeur de la chaîne (Fig. 5) [7,10]. Ce phénomène s'accompagne d'un processus d'extrusion facilité par le découplage induit par le sel d'Hormuz, à la base de la couverture à l'est du KFS. Ainsi, le mouvement décrochant le long de la MRF est transmis et distribué à travers le Zagros oriental par l'intermédiaire du KFS et des failles associées en éventail. À l'échelle de la zone de collision, ce système de failles peut être perçu comme une terminaison en queue de cheval de la MRF. De ce fait, le KFS participe à l'accommodation du partitionnement de la convergence oblique à travers la collision alpine moyen-orientale [14].

Synthetic map of the fault system distributing slip of the MRF to the Zagros fold-and-thrust belt. Deflected axial traces of anticlines are shown.

Carte synthétique du réseau de failles distribuant le glissement de la Main Recent Fault à la ceinture de chevauchements du Zagros. Les axes des anticlinaux sont reportés.

1 Introduction

In oblique plate convergence, deformation may be partitioned between orogen-parallel strike-slip faults and thrusts. The Zagros fold-and-thrust belt of southern Iran is a young active collisional orogen that provides a particularly relevant case-study for examining the relations between far-field boundary conditions and internal strain partitioning within a mountain belt.

Here, we present an integrated study of part of the Zagros fold-and-thrust belt combining field structural and geomorphic investigation and SPOT satellite images analysis. The aim of this work is to assess the recent to active geometry and kinematics of the Kazerun Fault System (KFS), one of the longest NNE-trending active strike-slip faults that crosscuts the entire Zagros belt at a high angle [4,5,7]. This allows addressing its relations to active thrusting and orogen-parallel, strike-slip partitioned motion at the backstop of the fold-and-thrust belt submitted to high-angle right-oblique convergence.

2 Geodynamic setting

The northwest-trending Zagros fold-and-thrust belt results from the Neogene collision between the Arabian and Eurasian plates (e.g., [12]). The northeastern boundary of the belt coincides with the Main Zagros Reverse Fault (MZRF) that represents the backstop of the fold-and-thrust belt ([12]; Fig. 1).

GPS measurements indicate that the Arabian and Eurasian plates converge at around 50°E (Fig. 1). At this longitude, the Zagros records a NNE-trending shortening rate of about that is oblique with respect to the main fold-and-thrust belt strike ([16]; Fig. 1). Earthquake focal mechanisms [7,15] suggest that a significant part of the convergence obliquity is turned into slip on the northwest-trending Main Recent Fault (MRF), which runs south of, and parallel with the MZRF at least as far as 51°E to the east. This fault accommodates the orogen-parallel, dextral strike-slip component of the oblique plate convergence at the rear of the Zagros fold-and-thrust belt at a rate of 10–17 mm/yr (estimate by Talebian and Jackson [14]).

A set of north-trending faults that are basement structures inherited from a neo-Proterozoic tectonic phase, disrupts the northwest-trending longitudinal Zagros folds (e.g., [13]). Geomorphic evidence and focal mechanisms indicate that these right-lateral strike-slip faults are active and affect both the cover and basement of the belt ([4,5]; Fig. 2a). The most prominent of these faults is the KFS that stretches from the eastern termination of the MRF, in the North, to the Persian Gulf, in the South. The fault marks the boundary between two drastically different structural domains. The width of the belt west of the KFS is narrow (200 km), salt extrusions are lacking, suggesting the absence of the Hormuz Salt at depth [13] and earthquakes are localised on major thrust faults (e.g., [7]). By contrast, to the east of the fault, earthquakes are distributed throughout the 300-km-wide Zagros fold-and-thrust belt [7,15]. The KFS is seismically active with a peak activity along its central part, where I ⩾ VIII historical earthquakes have been reported ([5,6]; Fig. 2a).

3 Fault segmentation

The KFS is made of three north-trending fault zones of equivalent length (-long). They have similar shapes with a general N170–180°E-trend and southern terminations bent southeastward (Fig. 2b). Their terminations split as fault splays and are generally connected eastward to the SE-trending thrust and ramp anticlines whose forelimbs are systematically overturned close to the KFS, implying an increase in south-verging reverse slip along the ramps towards the KFS.

The northernmost one reaches the eastern tip of the MRF through a narrow discontinuity describing a relay fault bend (Fig. 2b). Thirty kilometres further south, the High Zagros Fault (HZF) [7] merges with the northern segment close to the only releasing stepover of the fault zone (Fig. 2b). In contrast with the northern fault zones, several segments of the southern fault zone are arranged in an en echelon pattern and the northernmost one is bent northwestward into a thrust (Fig. 2b). This thrust fault makes up the Zagros front west of the KFS [7], but is shifted 100 km southward, east of the KFS. SSW of Khormuj, bending of a 95-km-long coastal anticline suggests the presence of a hidden, north-trending prolongation of the southern segment of the KFS at least up to the coast (Fig. 2b); bending shape suggesting a right-lateral displacement. It is interesting to note that, although fault zone lengths are comparable, large-scale segmentation displays a northward increase in the segment length, implying an increasing segmentation complexity southward.

4 Fault kinematics and stress regime

In order to further constrain the tectonic regime of the fault and the associated stress states, we performed a fault kinematic study at 28 sites distributed along the fault system. An inversion of each fault slip measurement set has been performed, using the method originally proposed by Carey [8]. Fault slip-vector inversions (Fig. 2c) indicate a right-lateral strike-slip regime along the KFS associated with a N35–40°E-trending and a thrust-faulting regime around the bent splay fault zone terminations. As these inversion results are consistent with earthquake focal mechanisms (Fig. 2a), they are interpreted to reflect the present-day stress regime.

5 Structural relations at the rear of the fold-and-thrust belt

In order to address the relations between the KFS, the MRF, and the MZRF, we compiled a detailed structural map covering their interaction zone (Fig. 3), based on SPOT images analysis, field observations and available geological maps. The rectilinear MZRF marks the northern limit of the interaction zone. At its southeastern tip, the MRF gives way to the NNW-trending northernmost segment of the KFS, and to the dextral oblique-reverse Semirom fault that trends at a low angle with respect to the eastern termination of the MRF (Fig. 3). GPS measurements and seismologic data provide evidence for no significant activity along the MZRF [6]. Consequently, this structural arrangement (Fig. 3) implies that the cumulated slip of the two strands of the MRF is transmitted to both the KFS and Semirom faults. These faults, together with the main segment of the northern KFS fault zone, define a wedge-shape domain (Fig. 3). Within the wedge, finite shortening trajectories are perturbed, suggesting an interference pattern around the bounding strike-slip and internal thrust/transpressive faults.

6 Discussion – conclusion

The finite pattern described above has been produced in two stages (Fig. 4): an early phase of westward reverse dip-slip along the northern Kazerun fault zone and a younger phase of strike-slip documented in the present study in relation with the MRF/KFS interaction. Evidence for the first phase regime is based: (1) on the occurrence of exhumed Jurassic formations on the hanging wall, whilst they are deeply buried (at ca minimum 5-km depth, [11]) west of the fault; (2) the 5- to 9-km offset of the top of the basement across the fault [3]. These movements, which took place at the time the northern KFS was the tectonic front of the High Zagros belt [6], started at least in the Late Cretaceous (i.e., the age of the detrital sediments of the Amiran formation that crops out on the eastern hanging wall of the fault [1]).

We relate the second deformation phase that initiated strike-slip along the northern KFS to the onset of slip along the MRF. Once cut by the MRF, the MZRF ceased to be active [9]. Anticlockwise rotation of Arabia allowed the MRF to propagate southeastward from the main Arabian indenter to reach and activate dextral strike-slip along the inherited KFS. This event is usually interpreted to have taken place at about 5 Ma [14], as a result of a regional re-organisation of the Arabia–Eurasia collision [2]. Indeed, field relationships from the central part of the MRF [9] indicate that strike-slip initiated during the Early Pliocene.

At that same time, the Semirom fault was activated and started transmitting part of the slip from the MRF, while the northern KFS absorbed the remaining part of horizontal strike-slip from along the MRF. Subsequent southeastward motion of the eastern KFS compartment produced southeastward thrusting within the wedge and northwest-trending shortening across the Semirom fault (as attested by the fault kinematic analysis, Fig. 2c), whilst reverse dip-slip shifted to on the Dinar thrust (i.e., the southern termination of the northern KFS fault zone, Fig. 4).

The structural and kinematic pattern shown in Fig. 4 (second stage) may be extrapolated to the scale of the Zagros fold-and-thrust belt (Fig. 5). Indeed, the structural wedge described in the Borujen area widens to the southeast into a regional fan-shaped fault pattern bounded to the west by the KFS (Fig. 5) [7,10]. We interpret this pattern to reflect distribution of slip from along the MRF to the fold-and-thrust belt through the thrust terminations of these strike-slip faults of the fan. The Hormuz salt formation that assists slip distribution throughout the belt to the east of the KFS acts as a low-resistance boundary allowing the extrusion-like process produced by transfer of orogen-parallel slip to the belt.

The model presented here is kinematically compatible with previous interpretations of active slip along the KFS. Talebian and Jackson [15] divide the Zagros fold-and-thrust belt into three zones that develop specific responses to plate convergence. Overall normal convergence is being recorded across the belt east of the fan-shaped fault pattern, whilst high-angle right oblique convergence would be active to the west of the KFS. The third zone would correspond to the fan-shaped fault pattern itself. Strike-slip-partitioned motion of oblique plate convergence, which is achieved by slip along the MRF within the western zone, is transmitted and distributed to the central and eastern zones by slip along the KFS and associated faults. This fault system may therefore be seen as an orogen-scale horse-tail strike-slip fault termination. In that sense, the KFS contributes to the fault system allowing partitioning of oblique convergence across the Middle-East Alpine collision belt and Arabia plate rotation associated with the westward extrusion of Anatolia [14] by transferring and distributing orogen-parallel dextral slip into the thrusts and folds of its frontal fold-and-thrust belt.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the ‘Intérieur de la Terre’ and Dyeti programs (INSU–CNRS, France) and the International Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Seismology (IIEES, Tehran, Iran). SPOT images (©CNES) were provided thanks to the ISIS program. We thank X. Le Pichon and an anonymous referee for their constructive comments on the manuscript.