Version française abrégée

Introduction

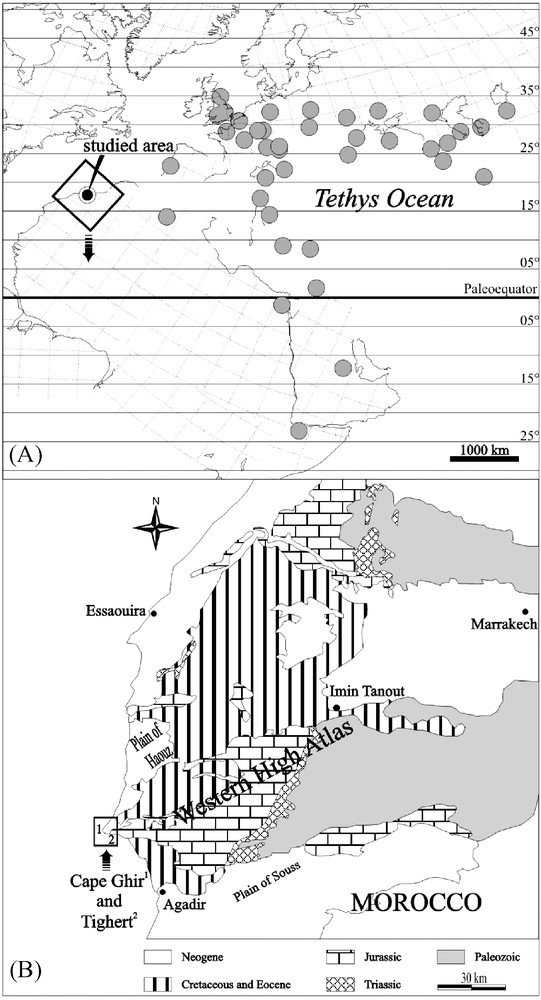

Au Jurassique supérieur (Oxfordien supérieur–Kimméridgien basal), l’existence de nombreux récifs coralliens sur les marges nord-téthysienne et nord-atlantique a été rendue possible par le développement de vastes plates-formes carbonatées à une latitude favorable au climat tropical (Fig. 1A) [12–14,20,21,27].

(A) The distribution of Oxfordian coral reefs known from the North Atlantic and Tethyan shelves. Location of the Cape Ghir and Tighert reefs is indicated. Reef distribution is projected on an Early Kimmeridgian paleogeographical background, after Thierry et al. [29], modified. (B) Schematic geological map of western Morocco, with the location of the Cape Ghir and Tighert coral reefs (after Ager [2], Adams et al. [1], modified).

Fig. 1. (A) Distribution des récifs coralliens oxfordiens, connus à ce jour, des marges téthysienne et atlantique, et localisation des récifs du cap Ghir et de Tighert (le contexte de la carte paléogéographique est Kimméridgien basal, d’après Thierry et al. ([29], modifié). (B) Carte géologique simplifiée de l’Ouest marocain et localisation des récifs du cap Ghir et de Tighert (d’après Ager [2], Adams et al. [1], modifiée).

Par rapport aux nombreux récifs de la marge eurasiatique, la marge africaine reste beaucoup moins peuplée et moins documentée. Une telle disposition est un défi pour qui veut comprendre comment les récifs réagissent, dans leur distribution et leur composition, à des évènements climatiques. Au Jurassique, le complexe récifal du cap Ghir (Maroc) occupe à cet égard une place particulière sur le continent africain, tant par sa position méridionale que par sa position occidentale, plus atlantique que téthysienne. Mieux connaître ses peuplements et son organisation apparaît dès lors comme un enjeu important pour comprendre la distribution des récifs et des constructeurs du Jurassique supérieur et les contraintes environnementales qui les déterminent. Situé à 40 km au nord d’Agadir, sur la côte atlantique, le long de la route d’Essaouira (Fig. 1B), ce récif a fait l’objet de quelques études stratigraphiques, paléontologiques et/ou sédimentologiques [3,16,24–26]. L’étude en est rendue difficile, car la tectonique et la présence de surfaces d’abrasion littorale du Plio-Pléistocène bouleversent la géométrie des corps sédimentaires. L’âge exact de ce récif demeure toujours incertain. Duffaud [7] et Ambroggi [3] décrivent des terrains d’âge « Argovien, Rauracien–Séquanien ». Ager [2] délaisse cette ancienne nomenclature et attribue le complexe récifal à l’Oxfordien supérieur–Kimméridgien inférieur. Adams et al. [1] placent le récif dans la formation de Lalla-Oujja, attribuée à l’Oxfordien moyen–supérieur. Hüssner [16] évoque un contexte stratigraphique kimméridgien, sans pour autant faire référence au récif. Ourribane et al. [25,26] et Ourribane [24] proposent plusieurs épisodes récifaux, datés de l’Oxfordien terminal au Kimméridgien inférieur sur la base de foraminifères (par exemple, Alveosepta jaccardi). De nombreux échantillons calcaires et marneux ont été prélevés pour des études palynologiques, mais la mauvaise conservation du matériel n’a pas permis d’affiner les datations du récif. Il s’avérait donc judicieux de voir ce qu’une étude de terrain prêtant une attention particulière aux assemblages coralliens pouvait apporter à cet ensemble de questions.

Contexte structural

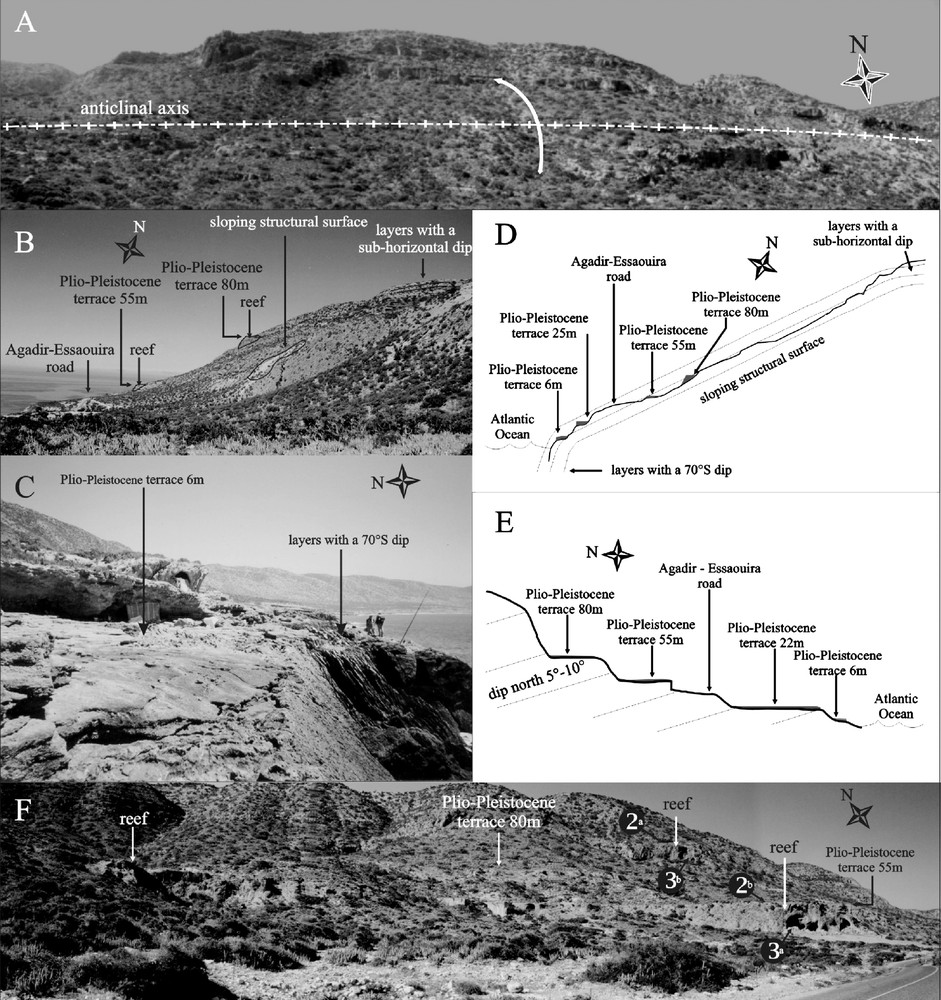

Le complexe récifal du cap Ghir, très localisé, se présente dans une charnière anticlinale d’axe est–ouest, près de Tighert (Figs. 1A et 2A–D ), se prolongeant probablement en mer vers l’ouest, alors qu’au nord, près du cap Ghir, les couches présentent un pendage général de 5 à 10° vers le nord (Figs. 2E et F). Tout le système a été entaillé par des transgressions marines plio-pléistocènes qui contrarient l’observation du caractère plissé des terrains jurassiques, notamment dans les niveaux bioconstruits à madréporaires. Il en résulte quatre terrasses observables tout au long du récif, aux altitudes de 6, 25, 55 et 80 m (Fig. 2B–F). Une représentation 3D de la topographie actuelle a permis de replacer les différents sites de récolte des échantillons de coraux, ainsi que les différents paramètres structuraux (Fig. 3A).

(A,B) Location of coral reefs and Plio-Pleistocene terraces in the frontal lobe of the Tighert anticline. (B) Dip of beds steepens progressively from sub-horizontal to 40° for the sloping structural surface and finally to 70° (2C), close to the Atlantic Ocean coastline. (D) Schematic cross-section summarizing the observations shown in Fig. 2A–C. (E) Schematic cross section near the lighthouse of Cape Ghir, showing the different Plio-Pleistocene terraces and a general dip of N5°–10° of the Jurassic beds. (F) Photograph from the upper part of the section in Fig. 2D, showing the position of reefs and higher morphological terraces visible above the Essaouira–Agadir road. Coral associations identified in locations (2)ab (3)ab characterized reef environments (see text and Fig. 3). Masquer

(A,B) Location of coral reefs and Plio-Pleistocene terraces in the frontal lobe of the Tighert anticline. (B) Dip of beds steepens progressively from sub-horizontal to 40° for the sloping structural surface and finally to 70° (2C), close to the Atlantic ... Lire la suite

Fig. 2. (A,B) Localisation des récifs et des terrasses plio-pléistocènes au sein de la charnière anticlinale de Tighert. (B) Le pendage des couches passe progressivement de la quasi horizontalité au sommet du relief à une quarantaine de degrés en milieu de pente structurale puis à 70° (2C) sur la côte de l’océan Atlantique, près de Tighert. (D) Profil schématique résumant les observations des Figs. 2A–C. (E) Coupe schématique près du phare du cap Ghir, montrant les différentes terrasses plio-pléistocènes et le pendage général des couches jurassiques de 5–10° vers le nord. (F) Photographie représentant la partie supérieure de la coupe de la Fig. 2D et localisant les récifs et les terrasses plio-pléistocènes au-dessus de la route Essaouira–Agadir. Les stations de récolte (2)ab (3)ab ont fourni des coraux, dont les associations caractérisent des environnements de récif (voir texte et Fig. 3). Masquer

Fig. 2. (A,B) Localisation des récifs et des terrasses plio-pléistocènes au sein de la charnière anticlinale de Tighert. (B) Le pendage des couches passe progressivement de la quasi horizontalité au sommet du relief à une quarantaine de degrés en milieu ... Lire la suite

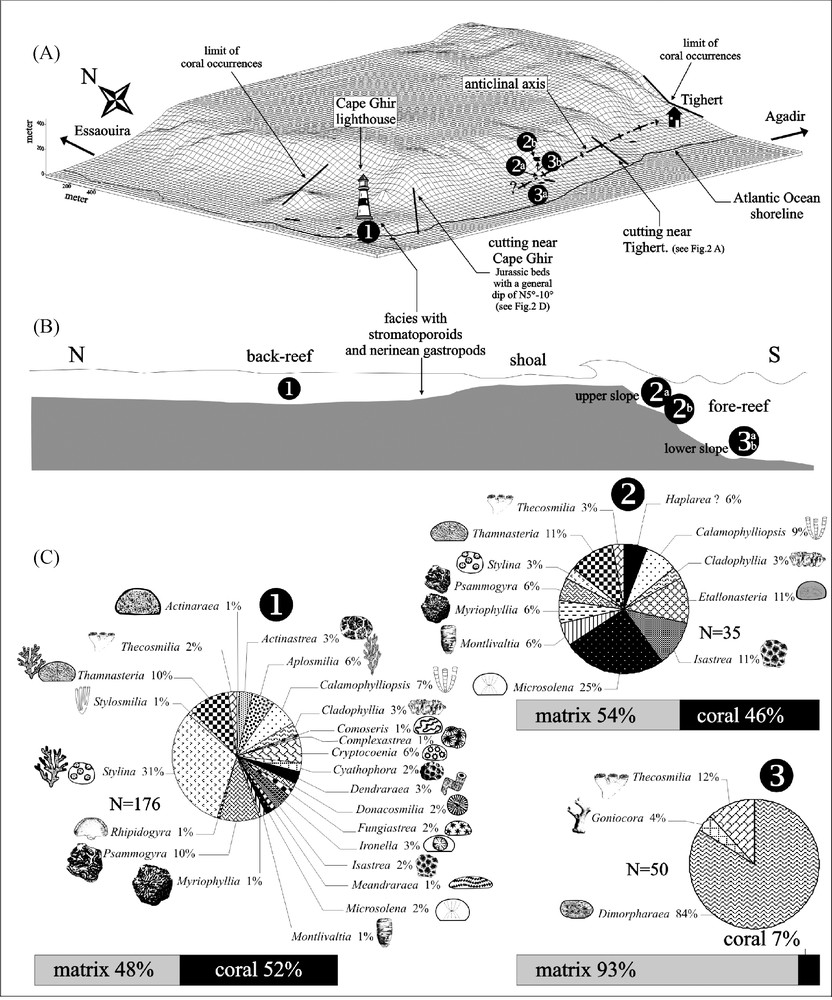

(A) Three-dimensional computer representation of the present-day topography between Cape Ghir and Tighert, seen in the direction of the anticlinal axis of Tighert. The coral sample stations (black dots) were surveyed using GPS. Location of sections from Fig. 2D and E, and the limits of coral occurrences to the east of Tighert and north of the Cape Ghir lighthouse. (B) Three reef environments are recognized by their respective generic diversity of corals. (C) Coral associations and genera of the different reef environments shown in Fig. 3B. Masquer

(A) Three-dimensional computer representation of the present-day topography between Cape Ghir and Tighert, seen in the direction of the anticlinal axis of Tighert. The coral sample stations (black dots) were surveyed using GPS. Location of sections from Fig. 2D ... Lire la suite

Fig. 3. (A) Représentation tridimensionnelle de la topographie actuelle du cap Ghir et de Tighert, montrant l’axe anticlinal de Tighert, les sites de collecte des échantillons de coraux (relevés par GPS), les localisations des coupes des Figs. 2D et E, et la disparition des coraux à l’est de Tighert et au nord du phare du cap Ghir. (B) Environnements récifaux mis en évidence par les associations génériques de coraux. (C) Associations coralliennes et genres identifiés au sein des différents environnements récifaux de la Fig. 3B. Masquer

Fig. 3. (A) Représentation tridimensionnelle de la topographie actuelle du cap Ghir et de Tighert, montrant l’axe anticlinal de Tighert, les sites de collecte des échantillons de coraux (relevés par GPS), les localisations des coupes des Figs. 2D et ... Lire la suite

Les associations coralliennes

Seulement neuf genres de coraux ont été mentionnés dans la littérature [3,16,24–26], alors que le complexe récifal du cap Ghir présente une abondante faune corallienne riche et variée en formes solitaires ou coloniales. La détermination systématique des 277 spécimens récoltés a permis d’identifier 27 genres (Fig. 3C). Dans l’état actuel des connaissances taxinomiques stratigraphiques et paléobiogéographiques, ces identifications ne permettent pas de préciser la datation avec certitude.

Au niveau du phare du cap Ghir, la faune corallienne est très diversifiée (24 genres, Fig. 3C). La roche comprend 52 % de corail et 48 % de matrice. Stylina est le genre le plus abondant sous forme de colonies rameuses. L’association est également caractérisée par la présence de colonies massives de très grandes tailles pouvant atteindre 180 (par exemple, Psammogyra ; 30°38′29N–9°53′29W, Fig. 5) ou 320 cm de diamètre horizontal (Complexastrea ; 30°37′98N–9°53′37W). Certains genres, tels que Cryptocoenia (ou Pseudocoenia), se présentent sous formes rameuses parfois de grande taille (colonie de 228 cm de diamètre ; 30°37′64N–9°53′22W). Cet assemblage faunique, marqué par l’abondance des formes plocoïdes, est typique d’un fonctionnement photo-hétérotrophe [9,23] d’arrière-récif ((1) sur la Figs. 3B et C).

Giant meandroid Psammogyra colony, 180 cm in horizontal diameter, near the lighthouse of Cape Ghir (30°38′29N–9°53′29W).

Fig. 5. Colonie méandroïde d’un individu du genre Psammogyra, mesurant 180 cm de diamètre horizontal, récolté près du phare du cap Ghir (30°38′29N–9°53′29W).

Un peu plus à l’est, les premiers assemblages observés juste au-dessus de la route d’Agadir–Essaouira (49 m d’altitude, (3)a sur la Fig. 3A) montrent une très faible diversité (trois genres, Fig. 3C). L’assemblage est dominé par le genre microsolénidé lamellaire Dimorpharaea (Fig. 6). Le volume squelettique est très faible par rapport à celui observé au niveau du cap Ghir (7 % corail, 93 % matrice). Cet assemblage peut également être observé 400 m plus à l’est à 208 m d’altitude ((3)b sur la Fig. 3A). L’environnement de ce type d’association est typiquement celui d’un bas de pente d’avant-récif [10,17,18].

Very thin lamellar microsolenids of the genus Dimorpharaea in the reef facies, in which the 55 m-high terrace was cut (see Fig. 2E), 500 m east of the Cape Ghir lighthouse (30°37′48N–9°51′42W)

Fig. 6. Coraux microsolénidés lamellaires très fins et larges du genre Dimorpharaea, observables dans le récif de la terrasse à 55 m d’altitude (voir Fig. 2E), 500 m à l’est du phare du cap Ghir (30°37′48N–9°51′42W).

Un assemblage corallien composé de 12 genres a été identifié à 219 m d’altitude ((2)b sur la Fig. 3A). L’association est caractérisée par des formes massives et de petite taille (Microsolena, Isastrea, Stylina, Etallonasteria, Thamnasteria et Psammogyra). Le volume squelettique ainsi que la diversité et la disparité caractérisent un environnement récifal de haut de pente d’avant-récif ((2)b sur la Fig. 3A–C).

Enfin, bien qu’il ne soit pas strictement corallien, nous avons reconnu un assemblage riche en stromatoporoïdes (stromatopores et Chaetetidae en boules centimétriques à décimétriques) et nérinées près du phare (Figs. 3A et B). Cet assemblage comprend aussi quelques coraux, surtout plocoïdes.

La comparaison avec la zonation récemment proposée par Lathuilière et al. [19] pour l’Oxfordien moyen du Jura français montre des positions similaires pour les genres Dimorpharaea, Microsolena et Stylina, mais aussi pour les nérinées (Figs. 3B et C). La rareté du genre Comoseris dans la zone la plus exposée contraste, en revanche, avec ce modèle.

Discussion

Nos observations structurales et paléontologiques du complexe récifal du cap Ghir permettent de suggérer la présence, au Jurassique, d’une tête de bloc basculé, moulée ensuite par la charnière anticlinale de Tighert [11]. Même si les failles bordières d’un tel bloc n’ont pas été directement observées, cette idée s’accorde avec le pendage des couches vers le nord, avec la présence de dépôts post-tectoniques dans ce même secteur nord, avec la forte dissymétrie de l’actuelle morphologie et aussi avec le contexte général extensif de l’Atlas Atlantique au Jurassique. Ce basculement a favorisé l’installation en position haute des coraux, qui ne sont plus observables à moins de 1 km au nord du phare du cap Ghir et 200 m après le village de Tighert, en direction d’Agadir (Fig. 3A). Les terrasses d’érosion horizontales plio-pléistocènes ont pu laisser conclure à une succession d’épisodes récifaux superposés en structures tabulaires [3,24–26], alors que la tectonique et l’étude des associations coralliennes montrent une redondance des mêmes environnements récifaux à différentes altitudes, notamment au-dessus de la route, 1 km après le phare du cap Ghir, en direction d’Agadir (Fig. 3A).

Les récifs passent latéralement à des séries stratifiées rythmiques, mais la superposition de deux épisodes récifaux biostratigraphiquement identifiables, l’un oxfordien, l’autre kimméridgien, n’apparaît plus nécessaire pour autant. Les associations coralliennes caractérisent typiquement, de par leur diversité, leur disparité et leur couverture (la surface occupée sur le fond, approchée à partir des proportions corail–sédiment), des environnements de récif : arrière-récif, haut de pente de l’avant-récif et bas de pente de l’avant-récif (respectivement (1) (2) (3)a (3)b sur la Fig. 3B). Ces environnements sont calqués sur une paléostructure d’échelle kilomètrique expliquant la distribution des communautés et la disparition des récifs au nord. Une organisation à l’échelle décakilométrique avec avant-récif à l’ouest et lagon à l’est [3,24–26] n’est pas nécessaire, pas davantage qu’une transgression marine venant de l’ouest [2]. Les associations coralliennes du cap Ghir se révèlent être une clef de lecture pour la géologie du récif ; elles sont significatives d’un environnement optimal pour le développement récifal, puisqu’elles ne montrent aucun stress environnemental qui soit partagé par l’ensemble des communautés.

L’étude fine des associations coralliennes, ainsi que les données de terrain combinées aux relevés GPS et à une représentation 3D du système, permettent de proposer l’hypothèse d’un complexe récifal zoné, correspondant à un modèle de faciès unique et qui ne rend plus nécessaire la succession chronologique de deux épisodes différents et biostratigraphiquement distinguables avec leur propre modèle de faciès [22].

1 Introduction

The Late Jurassic was a warm period with equable climates dominated by a greenhouse mode [12–14,27]. The wide latitudinal distribution of coral reefs during the Late Oxfordian and Early Kimmeridgian (Fig. 1A) supports this view of climatic conditions [5,6,20,21]. A tropical climate favored the development of extensive carbonate platforms and the installation of coral reefs at convenient tropical latitudes on the Tethyan and North Atlantic continental shelves [28].

On the African shelf, coral reefs are less well represented and not as well documented as on the Eurasian shelf [21]. We studied these coral reefs and their scleractinian assemblages to understand better their distribution patterns under the aspect of changing climates. The coral reef complex of Cape Ghir (Morocco) is of particular interest, because of its southerly and extreme westerly paleogeographic position on the eastern shelf of the freshly opening northern Atlantic Ocean. Detailed knowledge of the faunal composition and of the organization of this reef are helpful for a better understanding of the distribution and the limiting environmental factors of other Upper Jurassic coral reefs.

The coral reef complex of Cape Ghir is located at the coast of the Atlantic Ocean, 40 km north of Agadir, along the road to Essaouira (Fig. 1B; sheet of Taghazoute 1:50 000). This reef complex was already subject to several preliminary stratigraphical, paleontological and/or sedimentological studies [3,16,24–26], its study being particularly difficult due to local tectonics and to the presence of a number of Plio-Pleistocene abrasional coastal terraces, which considerably modified the geomorphology of the outcropping rocks and whose exact age remains uncertain. Duffaud [7] and Ambroggi [3] described beds attributed by them to the “Argovian, Rauracian–Sequanian”. These ages were based on perisphinctids collected above the uppermost of the coral build-ups seen in the outcrops. Ager [2] attributed the coastal reef complex to the Late Oxfordian–Early Kimmeridgian. Adams et al. [1] proposed to place the reefs in the Middle–Late Oxfordian Lalla Oujja Formation. Hüssner [16] suggested a Kimmeridgian age for the beds, but did not mention the reefs. Based on the foraminiferal associations (Alveosepta jaccardi, Everticyclammina sp., Nautiloculina oolithica..), Ourribane et al. [25,26] and Ourribane [24] suggested about three successive reef-building events of Late Oxfordian and Early Kimmeridgian age. We collected numerous samples of limestone and variegated marls for palynological studies, but the unsatisfactory preservation of the material did not result in a more precise age of the reefs.

Then, it was judicious to consider how a field study with a special attention to coral assemblages could improve this wide set of questions.

2 Structural context

The reef complex of Cape Ghir crops out along the southern flank of an east–west-trending anticline between the village of Tighert and Cape Ghir (Figs. 2A–D and 3A), with a probably westerly continuation into the Atlantic Ocean. Near Cape Ghir, the Jurassic beds show a general dip of N 5 to 10° (Figs. 2E and F). Here, the anticline assumes the shape of a box fold [2]. Fairly rapid sea-level oscillations must have occurred in a young geological past. As a result, the present gross geomorphology of the southern flank of the anticline is overprinted by a number of raised marine terraces formed during Plio-Pleistocene transgressions. Most terraces are covered by a coquina of well-preserved mytilid shells dating from the time of terrace formation, which are well exposed in the neighborhood of the village of Tighert. The terraced geomorphology is obscuring the stratigraphical and facies relationships when making field observations of the underlying Jurassic beds, especially within the reef build-ups. Four distinct terraces can be observed at the following altitudes: 6, 25, 55, and 80 m (Figs. 2B–F). Plotting the coral outcrops on the present-day topography generated by a 3D computer representation permitted to place the different coral sample stations and the different structural parameters of Fig. 2 (Fig. 3A).

3 The coral associations

Until recently, only nine coral genera were known from Cape Ghir [3,16,24–26], though this reef complex bears an abundant and highly diverse fauna of solitary and colonial scleractinians belonging to the following morphotypes: phaceloid, plocoid, cerioid, meandroid, thamnasterioid, and dendroid. The systematic treatment of the 277 specimens collected permitted recognition of 27 genera (Fig. 3C). The present state of taxonomic, stratigraphic and paleobiogeographic knowledge does not allow a firm dating. Corals were collected along several-metre-long transects, in which we measured the following parameters for each individual colony: width, thickness on the transect line, maximal thickness, and the percentage of sediment matrix in the coral association (as represented by the distance between adjacent coral specimens; Fig. 3C).

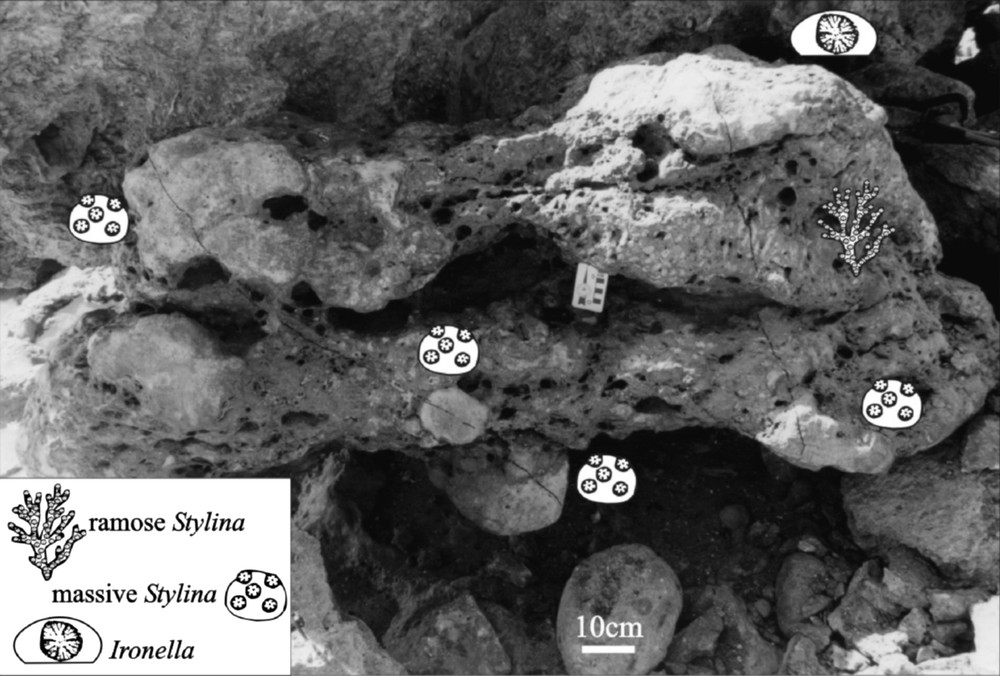

Along the coastline near the lighthouse of Cape Ghir, a first coral association is highly diverse (24 genera, Fig. 3C) and occupies 52% of the volume against 48% matrix. Stylinid corals are the most abundant (31% of branching and massive Stylina colonies, e.g., Fig. 4, and 1% of Stylosmilia), followed by rhipidogyrids (Psammogyra, Aplosmilia and Rhipidogyra). Other massive corals are also well represented by Thamnasteria (10%). Very large colonies of Psammogyra were often encountered, reaching up to 180 cm in horizontal diameter (30°38′29N–9°53′29W; Fig. 5). A giant colony of Complexastrea was found near the present tidal flat of the Atlantic Ocean, setting a world size record for a Jurassic reef coral, attaining 320 cm in horizontal diameter (30°37′98N–9°53′37W). This colony shows well-preserved growth bands, which permit to determine an average growth rate of 0.25 cm yr–1 and a total age of the colony amounting to 640 years. Some genera such as Thamnasteria (10%) and Cryptocoenia (6%) were represented either by ramose or massive colonies. A ramose specimen of Cryptocoenia reaches 228 cm in horizontal diameter (30°37′64N–9°53′22W). Some thickets of the phaceloid genus Calamophylliopsis (10%) were found at the Atlantic coastline east of the lighthouse reaching over 200 cm in horizontal diameter (30°37′64N–9°53′22W). This coral association is typical for a phototrophic-heterotrophic back-reef environment [9,23] (see in Figs. 3B and C).

Outcrop in the coral association of the Cape Ghir back-reef (30°37′76N–9°53′34W), with Stylina as the most abundant genus.

Fig. 4. Affleurement de l’association corallienne d’arrière-récif du cap Ghir (30°37′76N–9°53′34W), avec Stylina comme genre le plus abondant.

East of Cape Ghir, the first coral assemblage seen just above the Agadir–Essaouira road (at 49 m of altitude, N30°37′48–W9°51′42; see (3)a in Fig. 3A) shows a very low coral diversity (three genera, Fig. 3C). This second coral association is dominated by colonies of the lamellar microsolenid genus Dimorpharaea (84%) that developed very thin and platy colonies (average thickness 0.8 cm and width 14 cm; Fig. 6). The skeletal volume is also considerably low in comparison with that found in front of the lighthouse coastline (7% coral–93% matrix) versus 52% coral–48% matrix). This same assemblage can be found again 400 m further to the east at an elevation of 208 m above present sea level (N30°37′75–W9°51′49; see (3)b in Fig. 3A). This assemblage corresponds to a typical environment at the lower fore-reef slope [10,17,18].

A third coral association of 12 genera was identified 219 m above present sea level (N30°37′78–W9°51′45; see (2)b in Fig. 3A). This association is characterized by massive and small colonies such as Microsolena (25%), Isastrea (11%), Stylina (3%), Etallonasteria (11%), Thamnasteria (11%), Myriophyllia (6%), and Psammogyra (6%; see (2)b in Fig. 3C). The colonies of Psammogyra never exceed a size of 30 cm in comparison with those of Cape Ghir (near the lighthouse), which often surpass 100 cm in horizontal diameter. In the Recent, this variability of size within the same genus depends on the particular reef environments (back-reef, surf zone, upper fore-reef, lower fore-reef, etc.). This is confirmed by personal observations on the genera Porites and Acropora in modern reefs of the Réunion Island [30]. It is attributed to the effects of wave exposure and/or light availability.

Some elements of this Upper Jurassic coral association (see (2)b in Fig. 3A and B) have also been observed at 55 m of altitude on the top of the reef (N30°37′48–W9°51′42, see (2)b in Fig. 2F), just above the Essaouira–Agadir road, some 500 m east of the lighthouse. Here, the Plio-Pleistocene terrace probably truncated the shallower coral assemblage above (see (2)b on Fig. 2F). The skeletal volume, as well as the diversity and disparity (more massive, sturdy, and smaller colonies than in the back-reef), characterizes a reef environment of an upper fore-reef slope ((2)a in Fig. 3B).

Finally, in spite of the fact it is not strictly coralline, we recognized another assemblage rich in stromatoporoids (centimetric to decimetric ball-shaped stromatopores and chaetetids) and nerineids close to the lighthouse (Figs. 3A and B). This assemblage also includes some corals, almost plocoid.

The coral zonation corresponds largely to this elaborated by Lathuilière et al. [19] in the Middle Oxfordian of the French Jura Mountains. Here, the coral genera Dimorpharaea, Microsolena and Stylina, and nerineid gastropods occupy similar positions in the transect. However, Comoseris colonies are very rare at Cape Ghir, where this genus is only found in the back-reef environment, representing here about 1% of the coral association. This contrasts with the observations in the French Jura Mountains, where Comoseris is well represented in the exposed reef zone as well as in a symmetrical position in the back-reef.

4 Discussion

The results of our paleontological and structural studies of the Cape Ghir reef complex support our suggestion of a tilted block of Jurassic rocks [11], which was later folded into the anticline of Tighert. Even if bordering faults of the block are not directly observed, this idea fits well with the general dip of beds toward the north, with the occurrence of a toplap with post-tectonic deposits in the northern area, with the strong asymmetry of the present relief and also with the general extensional context of Atlantic Atlas during the Jurassic. The tilting was already existing in Upper Jurassic time and probably provided the necessary topography for coral installation. Corals are totally absent in the Upper Jurassic beds less than 1 km to the north from the Cape Ghir lighthouse and 200 m east of the village of Tighert (Fig. 3A). The wide horizontal abrasional terraces of Plio-Pleistocene marine incursions add to the false impression of several successive reef-building events [3,24–26]. The study of local tectonics combined with detailed analyses of the coral associations reveal that the same stratigraphical level with the reef environments reappears more than once at several altitudes in the flanks of the anticline. This is well visible above the coastal highway just 500 m east of the Cape Ghir lighthouse (see (3)a (3)b in Fig. 3A and B). Laterally, this single level of reef facies is replaced by rhythmically stratified beds. A succession of two biostratigraphically distinct reef-building events is not supported by field evidence. Foraminifera previously used for distinction of Upper Oxfordian and Lower Kimmeridgian reefs turned out to be irrelevant tools [4]. The diversity, disparity, and coral cover (approximated by the proportion coral skeletons/sediment matrix) of the coral assemblages of Cape Ghir and Tighert are characteristic of the different environments of a coral reef complex: back-reef, upper fore-reef slope, and lower fore-reef slope (respectively (1) (2)ab (3)ab on Fig. 3B). These reef environments were deposited on top of an inherited kilometric paleorelief. They do not continue into the bedded facies, but disappear laterally, as can be best seen in the coastal slopes to the north of Cape Ghir. Neither the view of a several-kilometre-long reef complex with a westerly fore-reef and an easterly back-reef [3,24–26], nor a marine transgression from the west (suggested by Ager [2]) is supported by our observations. Near the lighthouse at Cape Ghir, the back-reef facies was replaced laterally by subtidal deposits with abundant nerineid gastropods, algal pisolites, and stromatoporoids. Coral diversity and disparity of the Upper Jurassic at Cape Ghir are similar to those encountered elsewhere on the northern Tethys shelf (see [8,9,15,21,23,31]). The distribution of the coral associations of Cape Ghir permits to interpret the structure and ecology of the reef. The coral associations, taken as a whole, do not show any peculiar environmental stress and are consequently indicative of optimum conditions for reef development.

A detailed study of the coral associations as well as a combined GPS survey with 3D representation of the structure revealed that the outcropping reef bodies correspond to diverging facies development at the same stratigraphic level [22]. It rules out the former view of more than one reef-building event, each with its own proper facies [3,24–26].

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 21-61834.00).

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier