1 Introduction

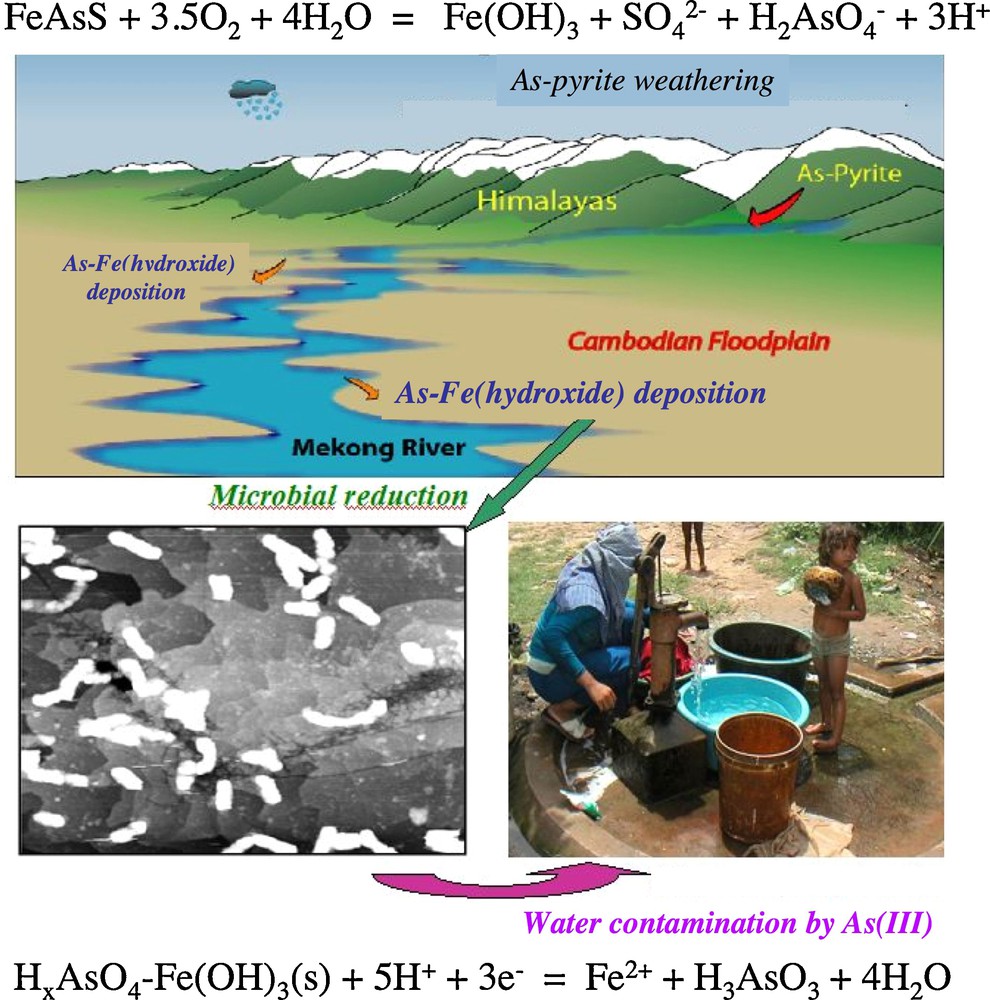

The field of Environmental Mineralogy has developed over the last decade in response to the recognition that minerals and the environment are inextricably linked in a number of important ways. These linkages are illustrated by the following statement: As-bearing minerals, natural Earth-surface processes, and humans have conspired to create the largest mass poisoning in human history in South and South-East Asia (section 6.2). Environmental Mineralogy integrates Mineralogy with Life Sciences, Environmental Geochemistry, Surface/Interface Geochemistry, and Geomicrobiology, with a focus on the interactions of minerals with the atmosphere, biosphere, and hydrosphere (i.e. the global ecosystem). It shares many of the molecular-level experimental and theoretical tools utilized by the multidisciplinary research area known as Molecular Environmental Science.

Environmentally significant minerals are present in soils and modern sediments, mineralized parts of living organisms, atmospheric aerosols, building materials and mineral resources, and they comprise an important compartment of the near surface environment of the solid Earth, sometimes referred to as the Critical Zone. Minerals, along with natural waters, are the primary repositories of the chemical elements in nature, including contaminants and pollutants. Thus they play an important role in controlling element behavior in the global ecosystem. Here we define contaminants as elements, molecules, or chemical compounds whose concentrations are above the geochemical background level but do not impact the health of organisms, and pollutants as elements, molecules, or chemical compounds present in sufficient quantity and of sufficient toxicity to impact the health of biological organisms (Alloway and Ayres, 1993). Another common term in Environmental Mineralogy/Geochemistry is bioavailability. We suggest the following definition that takes into account the molecular-level speciation of a contaminant (or pollutant), which can have a dramatic effect on its toxicity: Bioavailability, in the context of environmental mineralogy, is the degree of activity or amount of a pollutant that is in a molecular form available for activity in humans or other organisms. This definition distinguishes between pollutants and contaminants to which humans and other biological organisms may be exposed without significant uptake (i.e. not bioavailable) vs. those that are taken up physiologically and thus can potentially cause harmful health effects (i.e. bioavailable). Although Environmental Mineralogy plays an important role in determining the speciation of pollutants derived from minerals, it only provides information on the potential bioavailability of pollutants.

Because of their ubiquity in Earth surface environments, it is now well accepted that biological organisms play key roles in the weathering and transformation of minerals, the formation of biominerals, the cycling of elements, and the fate of environmental contaminants/pollutants. Thus a key component of Environmental Mineralogy is Geomicrobiology (sometimes referred to as Microbial Geochemistry), which focuses on the types and functions of microbial organisms that are present in different natural environments, including those that have been contaminated or polluted by anthropogenic activities, and how they interact with Earth materials and affect geochemical and mineralogical processes (Banfield and Nealson, 1997; Banfield et al., 2005; Lovley, 2000a). A major emphasis in this field is on how Bacteria and Archaea interact with inorganic and organic contaminants/pollutants (Lovley, 2000b). Such interactions can result in transformations of contaminants/pollutants into more (or less) mobile (and, therefore, potentially more (or less) bioavailable forms) and more (or less) toxic forms. These transformations can involve changes in oxidation state (redox reactions) of a metal(loid) and the molecular form of an inorganic solution or surface complex or xenobiotic organic pollutant, and precipitation of a solid phase that incorporates a contaminant/pollutant species. Microbial organisms can also cause transformations of redox-sensitive minerals (Hansel et al., 2003) that can result in the release of pollutants like As (Kocar et al., 2010). Such a process is implicated in the release of As into surface and groundwaters in South-East Asia (Fendorf et al., 2010; Islam et al., 2004), as is discussed in more detail in section 6.2 and in Charlet et al. (2011). Vaughan and Lloyd (2011) review some of the microbially induced redox transformations important in the environment, particularly those involving the oxidation of Fe(II) and the reduction of Fe(III).

Biomineralization, or biologically mediated precipitation of solid phases, is another important process in Environmental Mineralogy. Ca-bearing minerals (e.g., calcite, aragonite, hydroxyapatite, gypsum, whewellite [CaC2O4•H2O]) comprise the largest class of biominerals because of the important role of Ca in cellular metabolism (Weiner and Dove, 2003). Other important biominerals besides the carbonates, phosphates, sulfates, and oxalates include amorphous silica, metal sulfides, and the iron and manganese (oxyhydr)oxides (e.g., Lovley, 2000a,b; Spiro et al., 2010; Tebo et al., 2004), which can act as strong sorbents of heavy metal contaminants and pollutants. Detailed overviews of biomineralization can be found in Dove et al. (2003) and Benzerara et al. (2011).

Environmental Mineralogy is also concerned with major issues such as the remediation of polluted or contaminated sites; the sequestration of heavy metal/metalloid and organic pollutants/contaminants in ecosystems; and the disposition of waste (industrial, nuclear, etc.). In addition, the development of novel technologies poses potential threats to organisms (e.g., the use of engineered nanomaterials: section 5). Addressing such issues requires molecular-scale knowledge about biogeochemical processes at mineral and nanomaterial surfaces that can transform pollutants into less (or more) toxic forms. It also requires knowledge of the defective nature of minerals, the structural chemistry of disordered materials (nanophases, glasses, gels, metamict minerals) and aqueous solutions, and the speciation of trace elements in minerals, natural organic matter, and aqueous solutions. Although not usually considered part of “classical” mineralogy, Environmental Mineralogy is emerging as an important subdiscipline that helps explain the functioning of biogeochemical systems, the interplay between contaminant and pollutant release/sequestration/transport, and the impact of certain minerals or the elements they contain (or release) on human health.

The relevance of Environmental Mineralogy to human health is illustrated by the recognition that some minerals, such as asbestiform amphiboles and certain fibrous zeolites (e.g., erionite), may pose significant health hazards to humans when inhaled (Guthrie and Mossman, 1993). In addition, a wide variety of minerals and Earth materials such as coal contain contaminants/pollutants (Cr, As, Se, Hg, Pb…) that can be released into the biosphere as a result of natural chemical weathering or human activities. For instance, 800 tons of fly ash not captured by particulate control devices in coal-fired power plants are released daily in the USA, China and India (Lester and Steinfeld, 2007). Fly-ashes contain known carcinogens (e.g., Cr and As in the forms of Cr(VI)O42− and As(III)O33−, respectively), whereas other pollutants released during the refining and combustion of fossil fuels (e.g., Hg, in the form of CH3Hg+, and Pb2+) can cause neurological damage (Plumlee et al., 2006). The emerging field of Medical Mineralogy and Geochemistry (Sahai and Schoonen, 2006) is closely related to Environmental Mineralogy. In addition, minerals are projected to play a major role in the long-term sequestration of CO2 from the burning of fossil fuels (Guyot et al., 2011), as well as in the long-term sequestration of nuclear waste materials (Ewing, 2011; Libourel et al., 2011; Montel, 2011).

In this paper we present an overview of Environmental Mineralogy, emphasizing the role of mineral surfaces in controlling the distribution of elements in ecosystems and the fact that mineral surfaces in the environment are rarely clean, but instead can be coated, in part, by inorganic and/or natural organic matter as well as microbial biofilms, which can potentially impact their chemical reactivity. In addition, we discuss the complexity of Earth materials and their roles in the biogeochemical cycling of elements (Stucki, 2011) or as sources of inorganic contaminants and pollutants. We also discuss the growing interest in environmental processes acting over geological time periods, leading to geochemical anomalies (Morin et al., 2001) and natural/historical analogues (e.g., Calas et al., 2008; Gilfillan et al., 2009) that provide insights about mineral formation and stability under a variety of conditions that cannot currently be simulated in the laboratory or with theoretical approaches. The environmental impact of natural nanoparticles, such as ferrihydrite, and manufactured or incidental nanomaterials is also briefly reviewed. We also present overviews of the environmental mineralogy of Hg, As, and U as a means of illustrating some of the environmental processes involving minerals in Earth-surface environments.

Additional details about Environmental Mineralogy may be found in a number of recent reviews (Banfield and Navrotsky, 2001; Cotter-Howells et al., 2000; Plumlee and Logsdon, 1999; Sahai and Schoonen, 2006; Vaughan and Wogelius, 2000).

2 Molecular Environmental Science and its relationship to Environmental Mineralogy

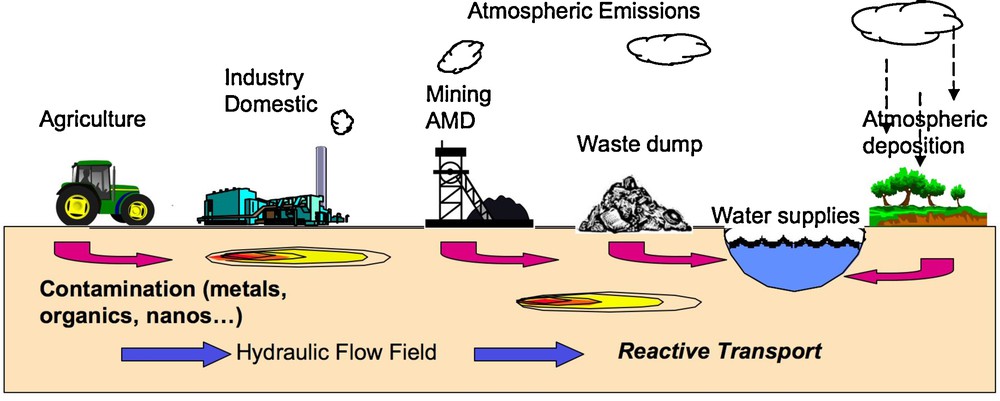

Molecular-scale studies of environmental problems involving contaminants and pollutants have grown in importance over the past two decades because of the need for fundamental information about their molecular-level speciation, the basic chemical and biological processes determining their behavior, and their effects on human health (Brown et al., 1995, 2004). The natural systems that require such studies are quite varied, as illustrated in Fig. 1, and usually quite complex. The main scientific issues involving contaminants/pollutants concern their sources, speciation, distribution, reactivity, transformations, mobility, biogeochemical cycling, and potential bioavailability. These issues ultimately depend on molecular-scale structure and properties. Basic understanding at this scale is essential for risk assessment, management, and reduction of environmental contaminants and pollutants at field, landscape, and global scales.

Field-scale schematic view of sources and transport of environmental contaminants (Brown et al., 2004). Potential sources due to accidental release/leaks of nanomaterials, heavy element, radionuclide or organic contaminants/pollutants are not presented on this sketch. AMD: Acid Mine Drainage.

Représentation schématique des sources et du transport des contaminants dans l’environnement (Brown et al., 2004). Les sources potentielles liées à des fuites ou des contaminations accidentelles de nanomatériaux, éléments lourds, radionucléides ou contaminants/polluants organiques ne sont pas représentées sur ce schéma. AMD : drainage minier acide.

The rapidly growing multidisciplinary field of Molecular Environmental Science has emerged due to the unique role that synchrotron radiation (SR) sources now play in addressing the above issues. Since the early use of SR in Earth Sciences (Brown et al., 1988; Calas et al., 1984; Waychunas et al., 1983), the very high intensity, brightness, and energy tunability of X-rays and VUV light from synchrotron storage rings permit element-specific spectroscopic, diffraction, and imaging studies of minerals and very dilute levels of contaminants and pollutants in environmental samples and model systems (Brown et al., 2006, for an overview of major user facilities). Results obtained from SR-based methods (often combined) will be presented in sections 3 and 4. Complementary imaging and spectroscopic methods comprise transmission and scanning electron microscopies and micro-UV-visible-NIR, micro-Raman, attenuated total reflectance- and micro-FTIR, Mössbauer, NMR, and EPR spectroscopies and macroscopic studies of biogeochemical processes. The rapid development of these methods, coupled with computational modeling including DFT methods (Balan et al., 2011), has led to unique information on the chemical processes that affect contaminant/pollutant elements and molecules, particularly at solid-water interfaces (Brown et al., 1999a), providing a great deal of basic data on the speciation and spatial distribution of toxic and radioactive species (Brown and Sturchio, 2002). Such information is beginning to play a critical role in setting environmental standards and in designing remediation strategies.

Fig. 2 is a schematic illustration of some of the molecular-scale processes that affect the fate of environmental contaminants and pollutants. Such processes range from dissolution of mineral particles in soils, to the binding or sorption of metal ions (M) and organic compounds (L) to mineral surfaces, which can effectively immobilize contaminants/pollutants and reduce their bioavailability (Brown et al., 1999b). Some pollutant elements such as Cr, As, Se, Hg, U can undergo oxidation or reduction when they interact with mineral surfaces (Charlet et al., 2011; Myneni et al., 1997; Wiatrowski et al., 2009) and organic compounds (Ravichandran, 2004). In addition, microorganisms and plants can have a profound influence on chemical reactions (Fortin et al., 2004). For example, microorganisms often play a major role in the degradation of organic contaminants/pollutants and in the oxidation and reduction of metal ions (Vaughan and Lloyd, 2011). The root-soil interface (rhizosphere – see circled area in the soil profile in Fig. 2) is an area of particularly intense chemical and biological activity where organic compounds are exuded by live plant roots. The pH can be as much as two units lower, and microbial counts can be 10 to 50 fold higher at the root surface than in the bulk soil a few millimeters away (Whipps, 2001). Thus, mineral weathering and the solubility of natural and anthropogenic contaminants/pollutants are generally greater in soils, where biological activity is higher, than in other compartments of the Critical Zone. An understanding of the molecular-scale mechanisms and rates of these processes requires knowledge of the speciation and distribution of contaminants/pollutants, the nature of mineral surfaces and colloidal particles, the types and distribution of organic compounds and microorganisms in soils and pore waters, and the effect of a host of variables on the rates of dissolution, adsorption, desorption, precipitation, degradation, and, more generally, acid-base, ligand exchange, and electron-transfer reactions.

Examples of molecular-scale environmental processes in soils and aquatic systems (Brown et al., 1995).

Exemples de processus environnementaux à l’échelle moléculaire dans le sol et les systèmes aquatiques (Brown et al., 1995).

3 The role of mineral surfaces in Environmental Mineralogy

3.1 The nature of the mineral-aqueous solution interface

The surfaces of minerals play a major role in Environmental Mineralogy. Reactions of mineral surfaces with aqueous solutions, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms are responsible for chemical weathering and the formation and evolution of soils. Mineral surface reactions also help control the sequestration, release, transport, and transformation of chemical elements, contaminants, and pollutants as well as biological nutrients in the biosphere. In addition, surface reactions are responsible for the degradation of building materials as well as mineral carbonation reactions that have sequestered CO2 over geologic time. Werner Stumm (1992) summed up the importance of the mineral/water interface: “Almost all the problems associated with understanding the processes that control the composition of our environment concern interfaces, above all, the interfaces of water with naturally occurring solids.” However, we know little about this interfacial region from direct observation at the molecular-level. Instead, we rely on models that began with Helmholtz (1879), who conceptualized the idea that colloids in contact with water develop a surface charge. This concept was followed by the idea that the collective charge of counter-ions in the aqueous solution surrounding a solid particle counteracts this surface charge (Chapman, 1913; Gouy, 1910). This led to the concept of a diffuse double layer (DDL) at solid- solution interfaces in which counter-ions (ions with a charge opposite that of the solid surface) and co-ions (ions with a charge of the same sign as that of the surface) are diffusely distributed in the double layer, with counter-ions increasing in concentration toward the solid surface and co-ions increasing in concentration away the solid surface, until some steady state concentration is reached at 10–20 Å from the interface (i.e. the bulk aqueous solution). Stern (1924) added the idea that the charge in the DDL is separated from the surface charge by the so-called “Stern layer”, because of the finite size of counter-ions, which limits their approach to the surface. Stern and later Grahame (1947) added the concept that aqueous ions can specifically adsorb at the Stern plane. Since formulation of the Gouy-Chapman-Stern-Grahame model of the DDL, a number of models that are variants of the original have been proposed, such as the Triple Layer model (Davis et al., 1978), the Multi Site Complexation (MUSIC) model (Hiemstra et al., 1989), and the Charge Distribution MUSIC model (Hiemstra and Van Riemsdijk, 1996).

Molecular-level characterization of the structure and ion distribution of the DDL at mineral/aqueous solution interfaces is a major challenge. Using synchrotron-based long-period X-ray standing waves (LP-XSW) to estimate the distance of ions above a complex solid/aqueous solution interface, Bedzyk et al. (1990) showed that the Zn(II) ions were distributed in a fashion qualitatively consistent with the Gouy-Chapman-Stern-Grahame DDL model. Trainor et al. (2002a, b) used a similar approach to show the greater affinity of Pb(II) for the α-Al2O3 (1-102)/solution interface relative to the α-Al2O3 (0001)/solution interface. In addition, when aqueous Se(IV) was present in these experiments, this build-up of Pb(II) in the DDL indicated a further enhancement of the affinity of Pb(II) for the (1-102) surface relative to the (0001) alumina surface. Other synchrotron-based studies (Fenter et al., 2000; Kohli et al., 2010 and references therein) have provided important insights about the distribution of Rb+ and Sr2+ in the DDL at TiO2 (rutile)/water, muscovite/water, and SnO2/water interfaces.

A schematic cross-sectional view of a metal oxide/aqueous solution interface, based on the Triple Layer model, is shown in Fig. 3. It illustrates the drop off in electrical potential with distance from the surface and the interfacial structure that develops in response to the charge on the metal oxide surface, including a plausible distribution of counterions and co-ions. The pHpzc (pH point of zero charge) of hematite powder is about 8.5 (Sverjensky, 1994), which means that at pH values below 8.5, aqueous anions are attracted electrostatically to the hematite surface and aqueous cations are repelled, whereas the opposite is true at solution pH values above 8.5. Interestingly, the pHpzc of the hematite (0001) single crystal surface is shifted down to 6.4 (Wang et al., submitted), which is speculated to be lower than that of hematite powder due to a lower defect density on the single crystal vs. powder surfaces of hematite.

Schematic view of the electrical double layer at a mineral/aqueous solution interface showing possible inner-sphere (Pb2+) and outer-sphere (Cl−, Na+, SO42−) complexes and the drop off of the electrical potential away from the interface (Hayes, 1987).

Représentation schématique du modèle de double couche électrique au niveau d’une interface minéral/solution aqueuse, montrant des complexes de sphère interne (Pb2+) et de sphère externe (Cl−, Na+, SO42), ainsi que la chute du potentiel électrique à distance de l’interface (Hayes, 1987).

When cation uptake occurs below the pHpzc and is not dependent on solution ionic strength, this behavior is interpreted as indicating the formation of strong, partially covalent bonds between the cation and reactive sites on the mineral surface (i.e. specific or inner-sphere surface complexation) (Brown and Parks, 2001). The opposite behavior of aqueous anions is suggestive of inner-sphere complexation of the anions (Hayes et al., 1988). Uptake of cations (anions) only above (below) the pHpzc and significant ionic strength dependence (indicating that the background electrolyte ions are interfering with uptake) is often used as evidence for formation of non-specific or weak outer-sphere adsorption complexes at mineral/aqueous solution interfaces. There is also the possibility of forming hydrogen-bonded adsorption complexes at mineral/aqueous solution interfaces, which should be intermediate in strength of bonding between inner-sphere and outer-sphere complexes (section 3.2).

A key question concerns whether the structure and composition of the hydrated mineral surfaces are the same as simple terminations of the bulk structure along a specific crystallographic plane or, instead, are relaxed or reconstructed relative to the bulk structure. The answer to this question had proven to be elusive until the first crystal truncation rod (CTR) diffraction study (Eng et al., 2000) showed that the hydrated (0001) surface of α-alumina is different from a simple (0001) termination of the bulk structure, with all hydroxyls (or water molecules) exposed at the surface coordinated by two Al3+ ions in six-fold coordination by oxygens and at least one proton (forming a hydroxyl group); in contrast, in the bulk structure each oxygen is bonded to four Al3+. In addition, significant structural relaxation was found in the surface region, extending down four atomic layers from the surface due, in part, to the effect of protons in this region (Aboud et al., 2011). Non-specular surface X-ray scattering studies (Fenter and Sturchio, 2004) have since been carried out on the following hydrated surfaces: α-Al2O3 and α-Fe2O3 (1-102) (Tanwar et al., 2007; Trainor et al., 2002a,b), α-Fe2O3 (0001) (Trainor et al., 2004), Fe3O4 (111) (Petitto et al., 2010), α-Fe2O3 (110) surface (Catalano et al., 2009), and α-FeOOH (100) (Ghose et al., 2010).

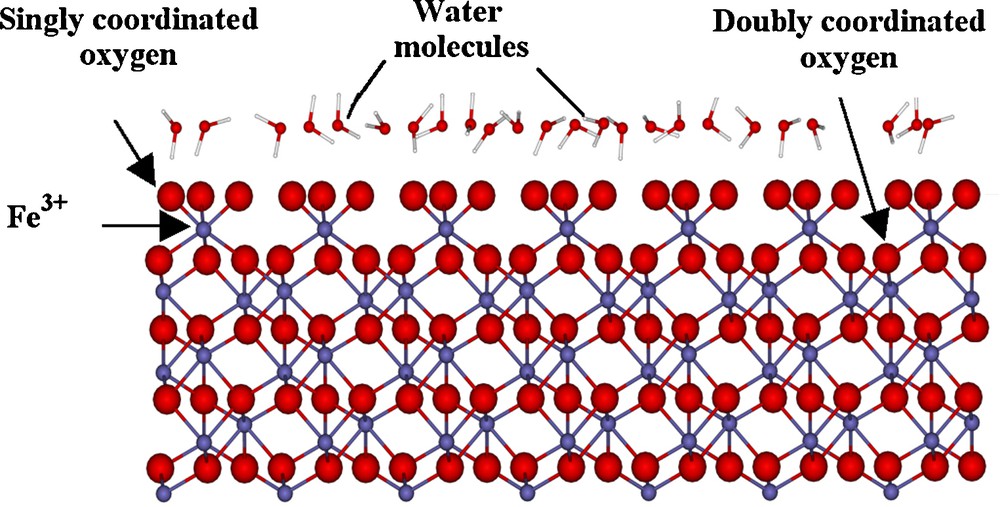

Trainor et al. (2004) combined a CTR study of the hydrated α-Fe2O3 (0001) surface with an ab initio thermodynamic study and found remarkable agreement between experiment and theory, both of which predicted a hydrated (0001) surface structure consisting of one third singly coordinated oxygens and two thirds doubly coordinated oxygens (Fig. 4). The presence of singly coordinated oxygens on the hydrated (0001) surface of α-Fe2O3, coupled with the finding of only two-coordinated oxygens on the hydrated (0001) surface of α-Al2O3, helps explain the significantly higher reactivity of the former to water (Liu et al., 1998) and aqueous cations such as Pb(II) (Aboud et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2007; Mason et al., 2009; Templeton et al., 2001). These studies have shown that the surfaces of anhydrous minerals undergo hydration, relaxation, and, in some cases, significant restructuring, whereas the surfaces of hydrous minerals don’t show much structural change in contact with water. Information about the surface structure of minerals under hydrated conditions provides a basis for understanding the binding modes and structures of metal ion adsorption complexes at mineral/aqueous solution interfaces.

Side view of the structure of the α-Fe2O3(0001)-water interface derived from crystal truncation rod diffraction data (Trainor et al., 2004).

Vue latérale de la structure de l’interface α-Fe2O3 (0001)-solution aqueuse, dérivée des données de diffraction par CTR (Trainor et al., 2004).

3.2 Sorption of contaminants and pollutants on mineral surfaces

Determining the mode of binding of metal cations and oxoanions to mineral surfaces is an important step in evaluating their potential to impact ground waters. Sorption processes at mineral-aqueous solution interfaces include both true surface adsorption and precipitation. When weakly sorbed (i.e. H-bonded or electrostatically bonded to mineral surfaces), reactive sites on mineral surfaces act as temporary “docking stations” for adatoms or admolecules, which can be “undocked” or released to solution by a change in solution ionic strength or pH. In contrast, when strongly adsorbed (i.e. forming direct covalent/ionic bonds with reactive sites on mineral surfaces), mineral surfaces can become long-term “docking stations” for adatoms, which are then effectively sequestered unless significant changes in the aqueous solution occur (e.g., dramatic lowering of pH due to acid mine drainage would result in the release of adsorbed cations). Fig. 5 is a schematic illustration of these different modes of sorption of a Sr(H2O)82+ aqueous complex onto the surface of hydrous Mn-oxides (HMO), including weak outer-sphere sorption in which the waters of hydration around Sr(II) are retained and the interaction is electrostatic, intermediate H-bonding interactions between the aqueous complex and the HMO surface, and strong inner-sphere bonding in which some of the waters of hydration are lost and the Sr(II) ion bonds directly to the HMO surface, forming partly covalent bonds.

Schematic illustration of different modes of Sr(H2O)82+ sorption onto hydrous manganese oxide (HMO) surfaces at pH 8, which is above the pHpzc of HMO, resulting in a negative surface charge (Grolimund et al., 2000).

Illustration schématique des différents modes d’adsorption de Sr(H2O)82+ sur les surfaces d’oxydes de manganèse hydraté (HMO) à pH 8, donc plus élevé que le pHpzc de HMO, ce qui donne une charge de surface négative (Grolimund et al., 2000).

Fe(III)- and Al-(oxyhydr)oxides are particularly effective sorbents of metal cations and oxoanions (Brown and Parks, 2001; Cornell and Schwertmann, 2003) because of their small particle size (high surface areas) and, in the case of cations, their relatively high pHpzc values (≥ 9) (Parks, 1965; Sverjensky, 1994), which means that the surfaces of these minerals are negatively charged over a broad range of solution pH values. Hydrous Mn-oxides are also effective sorbents for similar reasons (Weaver and Hochella, 2003), although their pHpzc values are significantly lower (4–7) than for the Fe(III)- and Al-(oxyhydr)oxides (Sverjensky, 1994).

Dissolution of minerals and release of ions into solution can lead to co-precipitation when the released ions combine with different ions in solution to form a precipitate that sequesters contaminant/pollutant ions (Towle et al., 1997; Trainor et al., 2000). XAFS spectroscopy and selective chemical extraction studies of Zn-contaminated soils in a smelter-impacted area of northern France showed that such co-precipitates form in Zn-contaminated soils and effectively sequester Zn (Juillot et al., 2003).

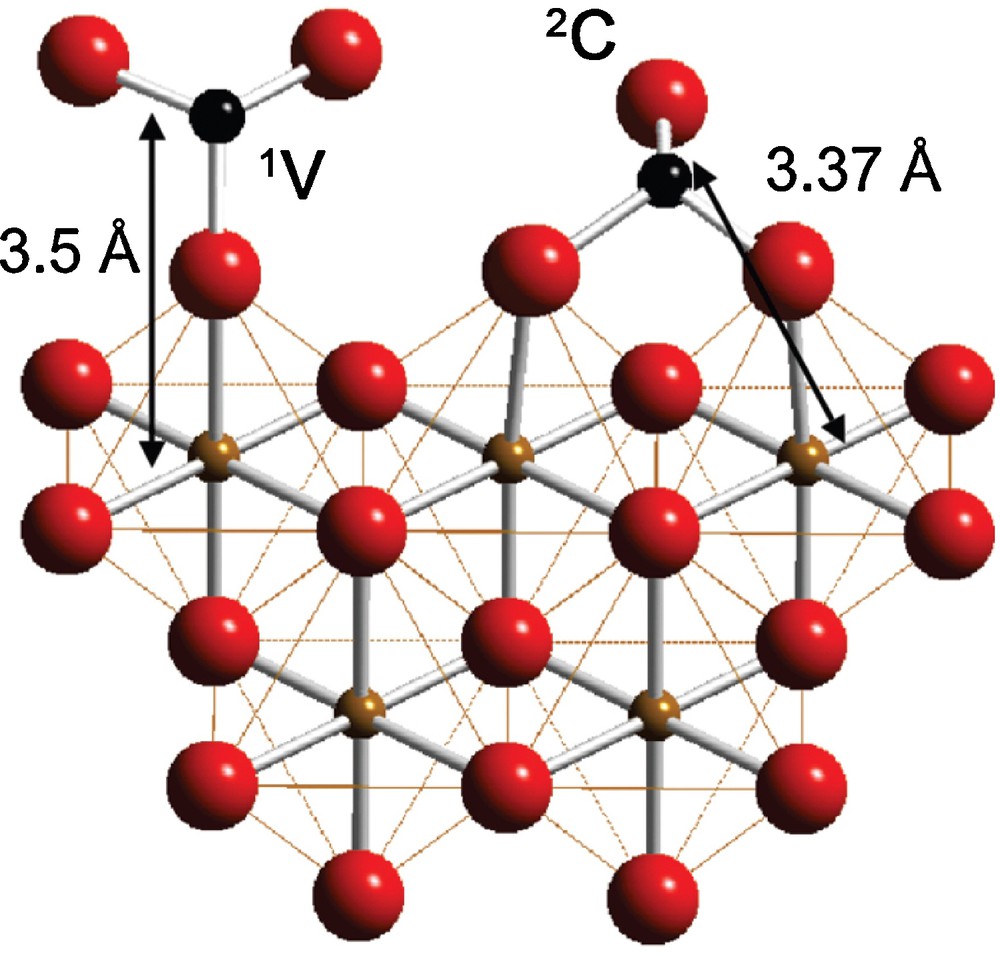

Synchrotron-based XAFS spectroscopy has become the method of choice for determining the dominant binding mode (i.e. inner- vs. outer-sphere, monodentate vs. bidentate, mononuclear vs. multinuclear) and average structure of metal ion and oxoanion sorption complexes at mineral/aqueous solution interfaces (Brown and Sturchio, 2002, for a review). The diversity of sorption processes is illustrated by As(V) and As(III) sorption at Mn-oxide/water interfaces (Foster et al., 2003) and Fe-oxide/water interfaces, including ferric (hydr)oxides (Foster et al., 1998; Ona-Nguema et al., 2005), magnetite (Morin et al., 2009), maghemite (Morin et al., 2008) and green rusts (Ona-Nguema et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010) (Fig. 6). The dominant modes of As adsorption include mononuclear mono-, bi- and tridentate bonding geometry (Wang et al., 2008), multinuclear As(III) sorption complexes and surface precipitates (Morin et al., 2009; Ona-Nguema et al., 2009), as further discussed in the contribution of Charlet et al. (2011).

Proposed structural model for arsenite adsorbed to the surface of green rust: As(III)O3 pyramids are sorbed via bidentate binuclear (2C) and monodentate mononuclear (1V) corner-sharing complexes. Fe-As distances are derived from EXAFS (Wang et al., 2010).

Modèle structural de l’adsorption de groupes arsénite à la surface d’une rouille verte: les pyramides As(III)O3 sont adsorbées sous forme de complexes bidenté binucléaire (2C) et monodenté mononucléaire (1V) partageant des sommets. Les distances Fe-As sont dérivées des données EXAFS (Wang et al., 2010).

Complementary information from grazing incidence (GI) XAFS spectroscopy and CTR diffraction shows that aqueous uranyl ions form predominantly monodentate and bidentate complexes on α-Al2O3 and α-Fe2O3 (1–102) surfaces (Catalano et al., 2005). The simultaneous presence of both inner- and outer-sphere arsenate sorption complexes at corundum/water and hematite/water interfaces was revealed for the first time using resonant anomalous X-ray reflectivity (Catalano et al., 2008). CTR diffraction has also been used to show that when aqueous Fe(II) sorbs on hematite (0001) and (1t02) surfaces, it occupies Fe(III) positions at the surface with Fe-O distances characteristic of the Fe(III) species (Tanwar et al., 2009).

Mineral surfaces can also take part in electron transfer reactions that result in oxidation or reduction of ions sorbed from solution and ions at redox-sensitive mineral surfaces. For example, aqueous Cr(VI) can be reduced to Cr(III) on magnetite surfaces via electron transfers from three Fe2+ ions at the magnetite surface to Cr(VI)O42− oxoanions at or near the magnetite-solution interface, resulting in the formation of a Cr3+-Fe3+-oxyhydroxide precipitate on the magnetite surface (Kendelewicz et al., 2000). Similarly, Hg(II) can be reduced to Hg(0) on magnetite surfaces (Wiatrowski et al., 2009) and Se(VI) to Se(0) on green rust (Myneni et al., 1997). In a somewhat more complicated electron transfer process, As(III) can be oxidized to As(V) on magnetite surfaces via an Fe2+-mediated Fenton reaction under oxic conditions (Ona-Nguema et al., 2010). Such transformations result in less toxic forms of Cr, Hg, As, and Se.

The results of these studies are essential for molecular-level interpretation of macroscopic uptake and surface complexation modeling studies of metal cations and oxoanions on mineral surfaces (Brown et al., 1999c). In addition, in natural systems such as polluted soils and mine wastes, XAFS studies have revealed the importance of metal cation, oxoanion, and actinyl sorption complexes on mineral surfaces, including Pb(II) sorption on Fe(III)-(oxyhydroxides) and Mn-oxides (Morin et al., 1999; Ostergren et al., 1999) and arsenate and arsenite sorption on Fe-oxides in mine tailings (Foster et al., 1998) and former industrial sites (Cancès et al., 2005) with important As-speciation variations with depth (Cancès et al., 2008).

3.3 Effect of surface coatings on mineral surface reactions

Although many sorption studies have focused on clean mineral surfaces, coated surfaces are the norm rather than the exception in natural environments: in soils, natural organic matter (NOM) (Davis, 1984) and/or microbial biofilms (Southam et al., 1995) are common and may coat mineral surfaces, although not necessarily to the extent of an effective monolayer (Ransom et al., 1997). Other minerals can also coat surfaces: CaCO3 coatings on magnetite can passivate surfaces and shut down electron transfer reactions because of the insulating nature of the coating (Doyle et al., 2004). Spectroscopic investigations of Fe-oxide coatings on kaolinite indicate that the nature of these oxides is sensitive to environmental changes after kaolin formation (Malengreau et al., 1994). The changes caused by such coatings (e.g., surface charge) may impact metal sorption and sequestration (Davis, 1984; Johnson et al., 2005). Davis (1984) generalized the impact of NOM on metal ion uptake on mineral surfaces using two extreme cases. In the open ocean and lakes where the concentration of suspended inorganic particles is low enough to approach complete coverage by adsorbed NOM, where metal uptake may be consistent with metal complexation by an adsorbed organic film. The opposite extreme might be found in a groundwater aquifer composed mainly of mineral particles and with low organic content, where mineral surface site concentration is high, and complexation between metal ions and mineral surfaces should be dominant. However, the above descriptions are based on one or more of the following hypotheses that need to be verified: NOM coatings on mineral surfaces form a layer impenetrable to metal ions; functional groups in NOM react with and block active surface sites on mineral particles, inhibiting the metal ion interactions with surface sites; functional groups in NOM out-compete reactive mineral surface sites for the metal ions. Long-period X-ray standing wave-fluorescence yield (LP-XSW-FY) spectroscopy studies have shown that at sub-micromolar Pb concentrations, Pb(II) sorption at a biofilm-mineral interface is dominated by complexation to high affinity metal oxide surface sites, despite the excessive number of potentially available binding sites in the overlying biofilm (Templeton et al., 2001). This result suggests that Pb(II) ions can penetrate through the biofilm coating and that reactive metal oxide surface sites have not been completely “blocked” or “out-competed” by binding sites in the biofilm. Although these findings appear to refute earlier hypotheses concerning organic or biofilm coatings, it is unwise to generalize based on a few experiments involving a specific type of organic layer or biofilm. Additional LP-XSW-FY studies of cation partitioning at biofilm-coated alumina and hematite surfaces using different bacteria (Shewanella oneideisis and Caulobacter crescentus) and additional cations (e.g., Zn(II), Ni(II), Cu[II]) have resulted in similar findings (Wang et al., 2009). Considering the various forms of NOM, a number of different situations could occur. For example, NOM layers (e.g., humic and fulvic acids) may have higher reactivity to contaminant ions (e.g., Pb[II]/As[V]) than the B. cepacia biofilms used by Templeton et al. (2001), since they contain larger numbers of functional groups that might out-compete mineral surface binding sites, as suggested by Davis (1984).

4 Natural vs. anthropogenic inputs of elements and contaminants into the biosphere

4.1 Some basics of chemical weathering and soil formation

Although physical, chemical, and biological processes act together during the weathering of the rocks exposed at Earth's surface, chemical processes are prevalent (Garrels and Mackenzie, 1971). Alteration/weathering mechanisms (Hering and Stumm, 1990) lead to the formation of divided phases, mainly clay minerals and Al-Fe-Mn oxyhydroxides, with the noticeable exception of durable minerals such as zircon (Balan et al., 2001). Weathering and formation of new alteration minerals impart Earth's surface materials (including soils, low temperature hydrothermal products, and sediments) with specific chemical and physical properties and control global hydrogeochemical cycles. Mineral-water interfaces play a fundamental role in this control, as most geochemical processes involve the transfer of chemical elements between fluids and solid phases (e.g., Hochella and White, 1990; Stumm and Wollast, 1990). The dynamics of these processes (such as crystal growth, dissolution, oxidation-reduction, adsorption, absorption, and exchange of heteroatoms) are governed by the detailed structure and chemical bonding of mineral surfaces (Hochella, 1990) (section 3.1). However, because of the duration of water-rock interactions – up to several million years for some lateritic soils (Balan et al., 2005) – ions sorbed at mineral surfaces can be later sealed into the mineral bulk structure as crystal growth proceeds. Crystal chemistry of minerals formed during alteration/weathering processes may then record physico-chemical conditions that prevailed during their formation (Muller and Calas, 1993), such as redox variations (Muller et al., 1995). Finally, as these minerals play a dominant role in the behavior of toxic metals at Earth's surface, understanding the crystal chemical location of these elements in minerals is a major concern in Environmental Mineralogy.

Laterite soils are widespread as a result of chemical weathering of various rocks under humid tropical conditions. The geographical distribution of laterite soils is related to present-day climates as well as to paleoclimatic conditions (Tardy et al., 1991). The weathering profiles consist of superposed horizons of variable extent, comprised predominantly of kaolinite associated with Al-, Fe-, and Mn- oxyhydroxides (Merino et al., 1993). A major question raised by laterites concerns the genetic relationships between these different horizons and their constituent materials. It is believed that the formation and evolution of laterites result from the permanent thickening of each horizon at the expense of the underlying one. This process is accompanied by a continuous differentiation of horizons upwards, with each horizon being dissolved at its top and with minerals precipitating at its base. As a result, kaolinites from one horizon originate from previously formed crystallites in the course of successive congruent dissolution and precipitations processes, which, at the scale of weathering profiles, develop from the saprolite towards the topsoil and participate to the soil organization at the profile scale (Nahon, 1991). Spectroscopic properties of impurities and defects in kaolinite (substituted Fe3+, sorbed Mn2+, radiation-induced defects) provide information on the geochemical changes during laterite differentiation (Herbillon et al., 1976), illustrating contrasting formation conditions between successive kaolinite generations. Kaolinites from Fe-oxide nodules, often found in the intermediate zone, have formed under less oxidizing conditions than those from the underlying saprolite and the topsoil zone (Muller et al., 1995). However, recent quantification of spectroscopic properties of kaolinite indicates that it is relatively resistant under tropical weathering conditions, with a slow rate of transformation at the time scale of laterite formation (Balan et al., 2007).

As underlined above, NOM plays a major role in mineral weathering due to chelation reactions at mineral/water interfaces. Organic colloids may then be transported at a regional scale, as illustrated in Fig. 7, which shows the confluence of the Rio Negro and Rio Solimoes Rivers that combine to form the Amazon River near Manaus, Brazil (Fritsch et al., 2011). The dark color of Rio Negro waters comes from the presence of organic colloids and particles, with a preferential complexation of Fe and Al to organic matter (Allard et al., 2004). Such Fe- and Al-speciation comes from waterlogged podzols developed upstream (Bardy et al., 2007). In contrast, the light brownish color of the Rio Solimoes arises from the presence of suspended Fe-oxides associated with sediments from the erosion of the Andes chain and of the soils developed on the corresponding alluvial zone. The importance of colloids in environmental sciences is discussed in section 5.

Multi-angle Imaging Radiometer (MISR) image of the confluence of the Rio Negro (from the northeast, with dark black water) and the Rio Solimoes (from the southeast, with light brown water) at Manaus, Brazil (from NASA/GSFC/JPL, Data and Information Services Center).

Images du radiomètre imageur multi-angulaire (MISR) représentant la confluence entre le Rio Negro (au nord-est, avec des eaux noir sombre) et le Rio Solimoes (au sud-est, avec des eaux brun clair) formant l’Amazone dans la région de Manaus, Brésil (d’après NASA/GSFC/JPL, Data and Information Services Center).

4.2 Contribution of minerals to biogeochemical element cycling and as natural sources of environmental contaminants and pollutants

Earth materials are inherently complex, both compositionally and structurally, at spatial scales ranging from cm to nm. Earth materials in the biosphere often consist of a mixture of solid phases (both crystalline and amorphous), NOM, microbial organisms, aqueous solutions, and gases, resulting in a variety of interfaces between minerals and other phases. Soils and coal are examples of this complexity (Fig. 2). Minerals and amorphous phases can incorporate impurity elements (and isotopes) in lattice sites, defects, and domain and grain boundaries. The influence of these impurities may be illustrated by the role of Al on the stability of diatoms, which account for as much as 90% of the suspended silica in the oceans and are responsible for 40% of oceanic C sequestration (∼1.5–2.8 Gton. C. yr−1) (Ehrlich et al., 2010). XAFS spectroscopy studies have shown that Al is structurally associated with silica, which indicates that Al is incorporated in diatoms during biosynthesis (Gehlen et al., 2002). In addition, there is a rapid post-mortem incorporation of Al in diatom frustules at the sediment-water interface (Koning et al., 2007). This substitution of Al for Si in diatoms directly influences the global Si biogeochemical cycle due to the inhibiting effect of Al on the solubility of biogenic silica, which is decreased significantly by only minor amounts of Al (∼0.1%).

Some common minerals may contain substituted contaminants or pollutants. Calcite can contain Pb2+ and UO22+ (Reeder et al., 1999, 2000), and can also accommodate anion substitutions, such as selenate (SeO42−) (Reeder et al., 1994), selenite (SeO32−) (Aurelio et al., 2010), arsenate (AsO43−) (Alexandratos et al., 2007), arsenite (AsO32−) (Roman-Ross et al., 2006), and chromate (CrO42) (Tang et al., 2007) substituting for CO32− groups in calcite. Another example is provided by pyrite, which can incorporate large amounts of As (up to ca. 10 wt%: Savage et al., 2000). DFT calculations predict AsS for S2 substitution and suggest that the presence of As will accelerate arsenian pyrite dissolution through a vacancy-controlled mechanism (Blanchard et al., 2007).

4.3 Geochemical anomalies: time effects

Heavy metals are sometimes concentrated in soils as a result of natural geochemical processes, leading to geochemical anomalies, which provide examples of regional, long-term environmental contamination. Under surficial conditions, the mobility and bioavailability of heavy metals are mostly driven by surface reactions on mineral and organic phases, as well as metabolic reactions within living organisms. These interactions occur through a variety of mechanisms, such as precipitation of mineral phases and sorption processes, and lead to large variations in the concentration of heavy metals in soils.

In situ determination of the concentration and speciation of heavy metals in such heterogeneous media as soils and other complex environmental samples remains a challenge. Concentrations are quantified using microanalysis techniques, chemical extraction methods, sometimes followed by detailed analysis of soluble species or thermodynamic analysis. The main difficulty in determining speciation comes from the fact that these elements are often at very low concentrations and occur in a variety of chemical forms in the same sample, including surface complexes. In favorable cases, speciation, including the presence of surface complexes, can be determined using spectroscopic techniques. A major question concerns the mechanisms underlying the long-term behavior of heavy metals in soils during historical times and geological time periods: are the mechanisms similar and can they be modeled at the laboratory time-scale?

In the first example (Fig. 8), As-rich soils (up to 500 pm) have developed over schists enriched in As over tens of km2 (Morin et al., 2002). Arsenic occurs in the soil as Ba-pharmacosiderite ([BaFe4(AsO4)3(OH)5•5H2O), which represents the dominant As-speciation near the saprolite. Adsorbed As(V) species were found to be dominant in the topsoil. This distribution suggests that adsorption on and coprecipitation with soil Fe-(oxyhydr)oxides are key mechanisms that inhibit As dissemination from the topsoil to the biosphere and hydrosphere, assuming acidic and oxidizing soil conditions, which ensure AsO43− inner-sphere adsorption complexes. The second example concerns soils developed over Pb-mineralized sandstones (Morin et al., 2001), which present Pb concentrations similar to those encountered in smelter-impacted soils (Morin et al., 1999). Plumbogummite (PbAl3(PO4)2(OH)5H2O) was found to be the most abundant Pb-bearing phase in all soil horizons and is also dominant at the bottom of the weathering profile, together with Pb2+–Mn-(hydr)oxide surface complexes. The importance of organic complexes increases near the surface. As phosphates are used to immobilize Pb in contaminated soils (Ma et al., 1995), the study by Morin et al. (1999) suggests that low solubility phosphates may be efficient long-term hosts of Pb in Pb-contaminated soils that have sufficiently high phosphorous activities to cause formation of these phases.

(left). Evolution of the concentration in As in soils (black circles) and pharmacosiderite (blue crosses) in the Echassières geochemical anomaly: at 70–80 cm depth, pharmacosiderite accounts for as much as 70% of total As, and its contribution is no more noticeable at depths smaller than 40 cm (Morin et al., 2002). (right) EXAFS-derived proportion of Pb speciation as a function of depth in the Largentière geochemical anomaly, normalized to the zirconium concentration to account for mass losses during weathering (Morin et al., 2001).

(gauche). Évolution de la concentration en As dans des sols développés sur l’anomalie géochimique d’Échassières (cercle noir). Les symboles en croix bleue représentent l’As contenu dans la pharmacosidérite: à 70–80 cm, la pharmacosidérite contribue au moins pour 70% de l’As total, alors que sa contribution n’est plus appréciable à des profondeurs inféreures à 40 cm (Morin et al., 2002, modifié). (droite) Évolution en fonction de la profondeur de la spéciation du Pb, dérivée de l’EXAFS, sur l’anomalie géochimique de Largentière, les concentrations étant normalisées à la concentration en Zr pour prendre en compte les pertes de masse lors de l’altération (Morin et al., 2001).

4.4 Post-mining and industrial contamination

Contamination from industrial, spatially localized sources characterizes specific forcing conditions (Morin and Calas, 2006). Mining and metallurgy can result in the release of heavy metals resulting from metal volatility during ore calcination which causes atmospheric contamination and further deposition after air transport (Jew et al., 2011; Morin et al., 1999) and from acid mine drainage (AMD) resulting from the oxidation and weathering of sulfide-bearing rocks, such as waste rock and mine tailings (Ostergren et al., 1999). Often mediated by microbial activity, AMD causes waters to become acidified and enriched in sulfate anions, metal ions and hydrous Fe-oxides (Corkhill and Vaughan, 2009). During this process, complex oxidation occurs, as illustrated by the two-stage As oxidation process:

| (1) |

Reaction (2) is slow, especially under acidic conditions, but may be catalyzed by the activity of bacteria such as Thiomonas sp. (Morin et al., 2003) and Leptospirillum ferrooxidans (Corkhill et al., 2008), and protozoa such as Euglena mutabilis (Casiot et al., 2004). Reaction (2) is important because As(V) is less toxic, less soluble, and adsorbs more efficiently than As(III) under acidic conditions.

Trapping of heavy metals by Fe/Mn oxyhydroxides is an efficient natural attenuation process, which reduces their concentration in AMD waters. The dynamics of metal speciation and concentration in AMD systems provides an interesting picture of the complex interplay among source terms, geochemical conditions, hydrological fluxes, and bacterial activity (Courtin-Nomade et al., 2005; Paktunc et al., 2004). Fe-oxides are efficient As traps in soils contaminated by industrially manufactured pesticides (Cancès et al., 2005, 2008), and Fe(III)-As(V) co-precipitates represent an efficient long-term As-trapping mechanism.

Agricultural activity is also affected by soil quality. The mobility and “bioavailability” of trace metal(loid) contaminants in soils are largely controlled by sorption reactions at the mineral/aqueous solution interface (e.g., formation of surface complexes and precipitates: section 3). Bioavailability is a dynamic property influenced by temporal changes in pH, redox potential, mineralogy, organic matter composition, bacterial activity, and climatic conditions (Reeder et al., 2006). Agricultural practices often involve using chemical compounds to improve the quality of crops; however, such additives can have adverse effects on soil and water systems. For instance, the release of various heavy metal(loids) (As, Cu, Zn…) through agricultural activities remains a great concern. It is necessary to control the leachability of these elements from pesticides, intensive animal raising, etc. so as to protect surface and ground waters from contamination, and reduce their bioavailability to humans. Fe- and Mn-oxides are often used for an efficient abatement strategy.

5 Role of nanominerals and mineral nanoparticles in Environmental Mineralogy

There is growing recognition that mineral nanoparticles (nanoscale versions of bulk minerals) and nanominerals (minerals or mineraloids that occur only in nanoscale forms – e.g., ferrihydrite) play major roles in environmental processes (Auffan et al., 2009; Banfield and Navrotsky, 2001; Hochella et al., 2008). This is true because of the enormous quantity of natural, incidental, and manufactured nanoparticles in natural waters, groundwater aquifers, soils, sediments, mine tailings, industrial effluents, and the atmosphere and the fact that such nanoparticles collectively have immense surface areas relative to μm-sized and larger particles of similar mass (Bottero et al., 2011). Because surface area is generally proportional to chemical reactivity, nanoparticles can dominate environmental chemical reactions, at least initially. Natural nanoparticles, which can form via inorganic and biological pathways (Jun et al., 2010), can be thought of as part of a continuum of atomic clusters, ranging in size from hydrated ions in aqueous solution to bulk mineral particles and aggregates of particles. Jolivet et al. (2011) discuss the growth mechanisms of aluminum oxyhydroxide nm-sized molecules in aqueous solutions.

There is also growing evidence that the structure and properties of nanoparticles change as particle size decreases (Auffan et al., 2009; Waychunas and Zhang, 2008). For example, γ-Al2O3 becomes the energetically stable polymorph of alumina rather than α-Al2O3 when particle surface area exceeds 125 m2g−1 (McHale et al., 1997). TiO2 nanoparticles exhibit differences in photocatalytic reduction of cations like Cu2+ and Hg2+ in the presence and absence of surface adsorbers like alanine, thiolactic acid, and ascorbic acid relative to bulk TiO2, due to the different surface structures (Rajh et al., 1999). Shorter Ti-O bonds and increasing disorder around Ti with decreasing size of the TiO2 nanoparticles suggest that the unique surface chemistry exhibited by nanoparticulate TiO2 is related to the increasing number of coordinatively unsaturated surface Ti sites with decreasing nanoparticle size (Chen et al., 1999). The structure of amorphous TiO2 nanoparticles are now modeled using a highly distorted outer shell and a small, strained anatase-like core with undercoordinated or highly distorted Ti polyhedra at the nanoparticle surface (Zhang et al., 2008). In nanoparticulate α-Fe2O3, surface Fe sites are also undercoordinated relative to Fe in the bulk structure; they are restructured to octahedral sites when the nanoparticles are reacted with enediol ligands (Chen et al., 2002), and may explain an increased sorptive capacity for aqueous Zn2+ relative to larger-sized hematite particles (Ha et al., 2009).

ZnS nanoparticles associated with acid mine drainage environments have been the focus of several structural studies. A pioneering study of 3.4 nm ZnS nanoparticles (Gilbert et al., 2004) found that structural coherence is lost over 2 nm and that the structure of the nanoparticle is stiffer than that of bulk ZnS, based on a higher Einstein vibration frequency in the nanoparticle. The surface region of the nanoparticle is highly strained. In a similar study of ZnS nanoparticles in contact with aqueous solutions containing various inorganic and organic ligands, stronger surface interactions with these ligands result in a thicker crystalline core and a thinner distorted outer shell (Zhang et al., 2010).

Ferrihydrite is arguably the most important natural nanomineral, occurring in both “2-line” and “6-line” forms in a variety of natural environments (Jambor and Dutrizac, 1998). The average size of “2-line” ferrihydrite nanoparticles in such environments is 1.5–3 nm (Cismasu et al., 2011). The structure of ferrihydrite “2-line” and “6-line” nanoparticles has been the subject of a number of X-ray scattering studies (Liu et al., 2010; Manceau et al., 1990; Michel et al., 2007) and is still controversial (Manceau, 2010; Rancourt and Meunier, 2008). Recently, Michel et al. (2010) carried out a synchrotron-based high energy (90 keV) total X-ray scattering and pdf analysis of synthetic “2-line” ferrihydrite that had been aged in the presence of adsorbed citrate at 175 °C. They found that after about 8-hours of aging, a new type of ferrimagnetic ferrihydrite with particles sizes of 12 nm was formed. After 12 hours of aging, transformation to hematite was complete. This form of ferrihydrite is characterized by lower water content, fewer Fe(III) vacancies, significantly higher magnetic susceptibility, and higher density than its “2-line” precursor. Based on these results, Michel et al. proposed a composition for “2-line ferrihydrite of Fe8.2O8.5(OH)7.4•3H2O and a composition for the aged ferrimagnetic form of ferrihydrite of Fe10O14(OH)2•∼1H2O. This study provides additional support for the “2-line” ferrihydrite structure proposed by Michel et al. (2007).

Several EXAFS and X-ray scattering studies of metal/metalloid ion (Zn[II], U[IV], As[V]) adsorption on “2-line” ferrihydrite nanoparticles have been carried out (Harrington et al., 2010; Sherman and Randall, 2003; Waite et al., 1994; Waychunas et al., 1995, 2002). These types of studies have the potential to provide indirect information on the structure of the surface of ferrihydrite nanoparticles. Additional studies include the formation of ferrihydrite from aqueous solutions and structural evolution to hematite nanoparticles (Combes et al., 1989, 1990), the evolution of ferrous and ferric oxyhydroxide nanoparticles in anoxic and oxic solutions, respectively, containing SiO4 ligands, which were found to limit the sizes of clusters formed (Doelsch et al., 2002) and the growth inhibition of nanoparticles of ferric hydroxide by arsenate (Waychunas et al., 1995) and by Ni(II) and Pb(II) (Ford et al., 1999). Whereas Ni(II) was found to be incorporated into the ferrihydrite nanoparticles, Pb(II) and arsenate were found to be dominantly adsorbed to the particle surfaces.

Colloidal particles, which are operationally defined as particles having at least one dimension in the submicrometer size range, include the size range of nanoparticles (Hunter, 1993). Colloidal particles play an important role in the transport of metal ions and organic contaminants/pollutants in the environment (Buffle et al., 1998; Grolimund et al., 1996). For example, colloid-facilitated transport of Pu is responsible for its subsurface movement from the Nevada Test Site in the western US to a site 1.3 km south over a relatively short time period (≈ 40 years) (Kersting et al., 1999). In addition, Kaplan et al. (1994a) found that colloid-facilitated transport of Ra, Th, U, Pu, Am, and Cm in an acidic plume beneath the Savannah River Site, USA helps explain the faster than anticipated transport of these actinides. This study also found that Pu and Th are most strongly sorbed on colloidal particles, whereas Am, Cm, and Ra are more weakly sorbed. EXAFS spectroscopy and SR-based XRF are now shedding light on how Pu and other actinide ions sorb on colloidal mineral particles and undergo redox transformations in some cases (Kaplan et al., 1994b). Another example of colloid-facilitated transport comes from recent laboratory column experiments of Hg-mine wastes, which showed that significant amounts of Hg-containing colloidal material from calcine piles associated with Hg mines in the California Coast Range can be generated by a change in aqueous solution composition, such as occurs when the first autumn rains infiltrate these piles (Lowry et al., 2004). In these latter studies, EXAFS spectroscopy, coupled with transmission electron microscopy characterization of the column-generated colloids, showed that the colloidal particles are primarily HgS rather than Fe-oxides on which Hg(II) is adsorbed.

Unraveling the structure and properties of natural, incidental, and manufactured nanoparticles will continue to be an active research area in Environmental Mineralogy, particularly as novel approaches (Gilbert et al., 2010; Michel et al., 2010) are employed and as we learn more about the ability of nanoparticles to facilitate the transport of contaminants and pollutants and their health impacts on ecosystems. Determining the structures of nanoparticles and nanoparticle surfaces is one of the grand challenges of all branches of nanoscience. This topic is currently being addressed using single particle scattering on the first hard X-ray free electron laser (the Linac Coherent Light Source) at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University (Bogan et al., 2008).

6 Environmental Mineralogy and behavior of mercury, arsenic, and uranium at Earth's surface

6.1 The life cycle of Hg from mining to global environments

Mercury (Hg) is a global pollutant that has attracted considerable attention among environmental scientists (Hylander and Meili, 2003; Morel et al., 1998), geoscientists (Kim et al., 2004a,b), and health professionals (Clarkson, 1998), particularly since the deaths of several thousand people in Minamata, Japan in the 1950s due to methyl-Hg exposure (Smith and Smith, 1975). Mercury enters aquatic and atmospheric systems via natural processes and anthropogenic activities (Gustin, 2003; Gustin et al., 2003; Hylander and Meili, 2003). Ionic forms of Hg are converted into the highly toxic monomethylated form (HgCH3+) by sulfate- and iron-reducing bacteria (Ekstrom et al., 2003; Marvin-DiPasquale, pers. comm.), which is then bioaccumulated and biomagnified up the food chain (Clarkson, 1998; Morel et al., 1998). Human intake of monomethyl Hg is primarily from consumption of fish such as tuna and swordfish (Clarkson, 1998). In addition, anthropogenic emissions of Hg have increased significantly during the last 150 years, primarily from coal combustion for production of electricity, resulting in the addition of 5,000 t/yr to the atmosphere currently (MIT Report, 2007). In addition, Hg mining has been a significant source of Hg pollution over the past 500 years (Hylander and Meili, 2003), and the legacy wastes of Hg mining in Hg-rich regions (e.g., the California Coast Range; Almaden Mining Region, Spain among others) continue to be significant sources of Hg to aquatic systems (Foucher et al., 2009) and the atmosphere (Gustin, 2003). Here we focus on the life cycle of mercury in mercury mining environments as an example of the behavior of a major environmental pollutant.

The Coast Ranges of Central California contain the largest Hg deposits in North America, with roughly two thousand inactive Hg mines, including the fourth and fifth largest mercury deposits in the world–the New Almaden Hg Mine in New Almaden, CA and the New Idria Hg Mine in South San Benito County, CA, which produced 38,000 tons and 20,000 tons of Hg, respectively, during their ∼120 years of operation (Rytuba, 2003). The California Coast Ranges consist of Mesozoic forearc and back-arc assemblages and mercury mineralization occurred subsequent to the transition of the Pacific Plate boundary from a subduction to a transform margin, associated with the formation of the Mendocino triple junction some 29 Ma ago. The accompanying slab window resulted in increased heat flow and widespread hydrothermal fluids, which scavenged, transported, and deposited Hg (Rytuba, 1995). The mercury ore, which is primarily cinnabar (HgS) with some elemental Hg (Hg[0]), is associated mostly with silica-carbonate rocks, produced by the carbonation of serpentinite, and consists of amorphous silica, Mg-carbonate alteration, and unaltered serpentinite. There is also association of cinnabar with hot springs mineral assemblages, kaolinite, alunite, and silica (Rytuba, 1995).

Beneficiation of Hg resulted in significant amounts of Hg(0), as the vapor, were typically lost during the roasting process. Schuette (1931) estimated that Hg(0) loss from each of the four rotary furnaces at the New Idria Mine was 85 lb/day, or about 2.3% of input. In this mine alone, stack loss of Hg(0) to the environment could have been hundreds of thousands of lbs of Hg(0), out of a total of 40,000,000 lbs of Hg(0) produced. Most of the lost Hg(0) was deposited in the local environment at the mine site.

Various biogeochemical processes can affect the speciation and cycling of Hg in such environments. Cinnabar is a highly insoluble mineral, as is its high temperature polymorph metacinnabar, with solubility products of 10−53.3 and 10−52.7, respectively (Krauskopf and Bird, 1995). Roasting of the ore produces Hg(0), which when deposited in soils in the form of small particles can be oxidized into relatively soluble phases such as montroydite (HgO). When Cl and S are present, a variety of soluble Hg minerals can be formed (section 6.2). Over 75 minerals with Hg as a major element have been identified (Parsons and Percival, 2005), so a number of other soluble Hg-chloride, oxychloride, and sulfate phases could also form. Associated pyrite and/or marcasite can undergo bacterially catalyzed oxidation, producing acid mine waters and ferrihydrite and other Fe(III)-containing precipitates.

This is the case at the New Idria Mine site, where an acid mine drainage pond has formed at the base of the main waste dump (Fig. 9) with pH values ranging from 2.0 to 4.5, depending on location in pond and season of year. Microbial organisms often live in such waters and, in the case of the New Idria site, form microbial biofilms on the water's surface (Fig. 9). These organisms cause enhanced dissolution of cinnabar and metacinnabar (Jew et al., 2006), releasing Hg(II), which can be methylated by sulfate-reducing bacteria, although there is little evidence that such methylation is currently occurring at this site. Hg(II) can also sorb onto Fe-oxide particles, such as the nanomineral ferrihydrite commonly present in such environments, and it can also form a variety of relatively soluble Hg salts. In addition, Hg(0) can vaporize from such sites, increasing the atmospheric burden of Hg (Gustin et al., 2003). Hg concentrations in the soils and waste materials at these sites can range from 100 to 1000's of ppm (Kabata-Pendias, 2001; Millan et al., 2006), with Hg present as both Hg(0) and Hg(II), with the latter being the predominant form (Schuster, 1991).

View of the main waste pile (gray slope on the right) and acid mine drainage pond (foreground) at the New Idria Hg Mine, located in South San Benito County, CA in the Diablo Range of the Central California Coast Range. The cloudy film on the water's surface is a microbial biofilm. The orange sediment consists of a mixture of ferrihydrite and schwertmannite. The white material coating this sediment at the water's edge is an efflorescence consisting mainly of Mg-Al sulfate hydrates.

Vue des haldes principales (pente grise sur la droite) et du bassin de drainage minier acide (premier plan) dans la mine de Hg de New Idria, localisée dans le South San Benito County, CA, Diablo Range du Central California Coast Range, USA. La surface trouble de l’eau est due à un biofilm microbien. Le sédiment orange est constitué de ferrihydrite et schwertmannite. Le matériau blanc qui recouvre ce sédiment sur les bords du bassin représente une efflorescence constituée essentiellement de sulfates hydratés Mg-Al.

EXAFS spectroscopy has played a major role in determining the molecular-level speciation of mercury in mercury mining regions (Kim et al., 2000, 2003). These studies have shown that cinnabar (α-HgS) and metacinnabar (β-HgS) are the main mercury-bearing species in these materials, with minor soluble mercury species, including montroydite (HgO), corderoite (Hg3S2Cl2), calomel (Hg2Cl2), egelstonite (Hg6Cl3O[OH]), mercuric chloride (HgCl2), terlinguite (Hg2ClO), and schuetteite (Hg3[SO4]O2). When these relatively soluble Hg-containing phases are present, Hg(II) is available for methylation by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Recent low temperature (77 K) EXAFS studies of these materials (Jew et al., 2011) have shown that Hg(0) is an important Hg species, comprising up to 25% of the total Hg species present by weight in some mine wastes and Hg-contaminated soils. This is not surprising because Hg(0) is often present in the unprocessed ore and at a few hot springs type mercury deposits is the primary ore rather than cinnabar (e.g., the Socrates Mine, Sonoma County, CA, USA). Hg(0) can also result from reduction of Hg(II) on magnetite (Wiatrowski et al., 2009).

A major pathway for mercury into the global environment is evasion to the troposphere (Gustin, 2003; Gustin et al., 2003; Hylander and Meili, 2003). Gustin (2003) has shown that substrate Hg concentration, rock type, and degree of hydrothermal alteration are the controlling factors in determining the magnitude of Hg emissions from natural sources, with meterological parameters (light, temperature, and precipitation) controlling diel trends. Gustin also concluded that elemental mercury is the dominant form (95%) of mercury emitted from the regions in Nevada studied. New Hg speciation data (Jew et al., 2011), coupled with Hg evasion measurements under light and dark conditions on the same samples, show that Hg emissions into the troposphere correlate positively with the amount of Hg(0) present in wastes, soils and sediments.

Although soluble Hg-containing species exist at low concentrations in soil solutions, most Hg(II) in soil is bound to solid phases (Kim et al., 2004a; Schuster, 1991) or to natural organic matter (NOM) (Kabata-Pendias, 2001). Mercury concentrations correlate with that of NOM in both organic and mineral soils (Grigal, 2003; Kabata-Pendias, 2001). Depending on the nature of NOM and its interaction in soils, it may affect Hg speciation and mobility. For example, complexation of Hg with dissolved NOM may result in enhanced leachability and drainage into water systems (Wallschlager et al., 1996). Soil NOM limits Hg(II) availability, thus inhibits the formation of methylmercury (Barkay et al., 1997). NOM also enhances reduction of ionic Hg(II) to Hg(0), directly or by enhancing photoreduction (Xiao et al., 1995), and therefore supports its volatilization and limits its availability for methylation.

Mercury binding to reduced sulfur groups has been suggested to be a major factor in determining Hg retention by NOM (Skyllberg, 2008). This assumption is based on quantitative estimation of reduced S groups using XANES measurements of soil NOM (50 to 78% of total S in NOM), combined with thermodynamic calculations. Further study using EXAFS has shown that Hg(II) and CH3Hg(II)+ preferentially bind to S in soil NOM at low concentrations. Only at higher Hg concentrations, following saturation of reduced S-containing groups, do O and/or N atoms take part in binding of Hg (Skyllberg, 2008). Interestingly, Hg is preferably bound to NOM even under sulfidic conditions (Miller et al., 2007). Hydrophobic interactions, incorporating the Hg-sulfide complex, have been suggested. Dissolved NOM and mercaptoacetate (containing a thiol group) were found to enhance cinnabar dissolution and inhibit its precipitation (Ravichandran et al., 1999), whereas acetic acid and EDTA had only a small effect on cinnabar dissolution. Enrichment of Hg in soil NOM with depth has also been reported (Grigal, 2003). The average concentration of Hg in the NOM of mineral soils (0.44 μg Hg per g NOM) is higher than that for organic soils, such as forest floor soils (0.29 μg Hg per g NOM). These observations point to a lower loss rate of Hg compared to C during NOM mineralization. Indeed, a recent study showed that degradation of glutathione was reduced dramatically when it was complexed to Hg and Ag, in contrast to rapid oxidation of complexes containing other metals (Hsu-Kim, 2007).

Roughly 20–30% of the elemental mercury produced by the mercury mines in the California Coast Ranges was used to amalgamate fine-grained gold following the California gold rush (1848–1855). The high-temperature retorting process used to separate gold from elemental mercury following amalgamation was relatively inefficient and as much as 8,000,000 lbs of elemental mercury was lost to the local environment in the Sierra Nevada Foothills. The legacy of gold mining in California includes this mercury, which is slowly being transported to San Francisco Bay via surface waters. Several molecular-level studies have shown that one of the most important species responsible for the transport of mercury in the California Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Foothills is nanoparticulate HgS (Lowry et al., 2004; Slowey et al., 2005). The presence of HgS nanoparticles in sediments and soils downstream from placer gold mining activities, where Hg(0) was used to extract fine-grained gold, suggests that Hg(0) is transformed to Hg(II) and combined with reduced S, perhaps from NOM, to produce nanoparticles of HgS (Slowey et al., 2005).

The above discussion shows that the life cycle of mercury in mercury mining environments is affected by a number of factors, including pH of surface waters; presence of iron- and sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (resulting in acid mine drainage and increased mobility of Hg[II]) and sulfate- and iron-reducing bacteria (resulting in methylation of Hg(II), the most toxic form of Hg in natural environments); types of mercury minerals present in the waste rocks, calcined material, sediments, and soils (e.g., Hg evasion into the atmosphere is correlated with the amount of Hg(0) in these materials); types of minerals associated with Hg-polluted sites (e.g., Hg(II) can sorb strongly on ferrihydrite, which can sequester Hg(II) under near-neutral pH conditions, and it can be reduced to Hg(0) on magnetite); amount of loss of Hg(0) to the local environment from gold mining activities; and type of country rock. Its transport to major water bodies is also dependent on a number of factors, one of the most important ones being the speciation of Hg.

6.2 As pollution in South and Southeast Asia–the largest mass poisoning in human history

Arsenic pollution of Holocene groundwater aquifers in South and Southeast Asia are impacting over 100,000,000 people who derive their drinking water from shallow, hand-drilled wells in the deltas of a number of major rivers in this region draining from the Himalaya to the north and northwest (Fendorf et al., 2010) (Fig. 10). The redox conditions at the depths in these deltaic sediments from which drinking water is pumped are typically anaerobic. The problem begins in the Himalaya to the north, where abundant arsenian pyrite is found naturally in the high-grade metamorphic and metasedimentary rocks and ophiolites (Fig. 10). Experimental and theoretical molecular-level studies of arsenian pyrites have shown that significant amounts of arsenic (> 1300 ppm) substitute for sulfur in pyrite and are locally clustered in the pyrite structure (Blanchard et al., 2007; Savage et al., 2000). The oxidation of arsenian pyrites results in the release of As3−, which is oxidized to As5+ in the form of protonated arsenate oxoanions. These arsenate oxoanions sorb strongly to Fe(III)-(oxyhydr)oxides (Cancès et al., 2005; Catalano et al., 2008; Charlet et al., 2011; Dixit and Hering, 2003; Foster et al., 1998; Morin et al., 2008), which can be transported in colloidal form via surface and groundwater aquifers. Such colloids are transported by the waters of the major rivers in South and Southeast Asia to their floodplains and deposited (Fig. 10). There is now broad acceptance that Fe(III) and As(V) in As(V)-sorbed Fe(III)-(oxyhydr)oxides can be bacterially reduced (Islam et al., 2004; Kocar, 2008; Kocar et al., 2010; Polizzotto et al., 2008) (Fig. 10). Such reduction, as well as reduction induced by organic carbon from human waste (Fendorf et al., 2010), in the As-polluted deltaic sediments in the affected areas of S. and S.E. Asia has resulted in the release of As(III) into groundwater, which is impacting the health of millions of people in these regions. Thus, as stated in the introduction, As-bearing minerals, natural Earth-surface processes, and humans have conspired to create the largest mass poisoning in human history in S and SE Asia. Additional details about the environmental mineralogy of As and its impact on humans can be found in the article by Charlet et al. (2011).

(top) Schematic drawing of the Himalayas, the Mekong River, and the Cambodian floodplain (Kocar, 2008), showing the breakdown of arsenian pyrite in the Himalayas, the transport of Fe(III)-hydroxide colloids with sorbed As(V) (referred to as As-Fe-hydroxide), and the deposition of As-Fe-hydroxide in the Cambodian floodplain; (lower left) Scanning tunneling microscope image of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 on a hematite (0001) surface (from K. Rosso, PNNL, pers. comm.); (lower right) Photograph of a water well in Cambodia that may be polluted by As(III) (Fendorf et al., 2010). A highly simplified version of the As-pyrite oxidation reaction and of the reduction reaction of HxAsO4-sorbed Fe(OH)3 are shown at the top and bottom of the figure, respectively.

(haut) Représentation schématique de l’Himalaya, du Mékong et de la plaine d’inondation du Cambodge (Kocar, 2008), montrant la déstabilisation de la pyrite arséniée dans l’Himalaya, le transport de colloïdes d’hydroxydes de Fe(III) avec As(V) adsorbé (désignés comme hydroxyde As-Fe) et le dépôt des hydroxydes As-Fe dans la plaine d’inondation du Cambodge; (bas, gauche) Image STM de Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 sur une surface d’hématite (0001) (d’après K. Rosso, PNNL, comm. pers.); (bas, droite) Photographie d’un puits d’alimentation en eau au Cambodge, pollué en As(III) (Fendorf et al., 2010). Une représentation simplifiée des réactions d’oxydation de la pyrite-As et de réduction de HxAsO4 adsorbé sur Fe(OH)3 est indiquée respectivement en haut et en bas de la figure.

6.3 Uranium

With the expected 3-fold expansion of nuclear power by the year 2050 to meet growing energy demands using a CO2-free energy resource, there will also be an increased environmental impact from the nuclear fuel cycle. The subsequent increases in the price of uranium (more than 10 times since 2003) translate into increased exploration and mining activity for uranium and a need to deal with the disposal of spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste, at the “front-end” and “back-end” of the nuclear fuel cycle, respectively. Environmental Mineralogy plays a key role in understanding and mitigating the environmental impact of an expanded nuclear fuel cycle.

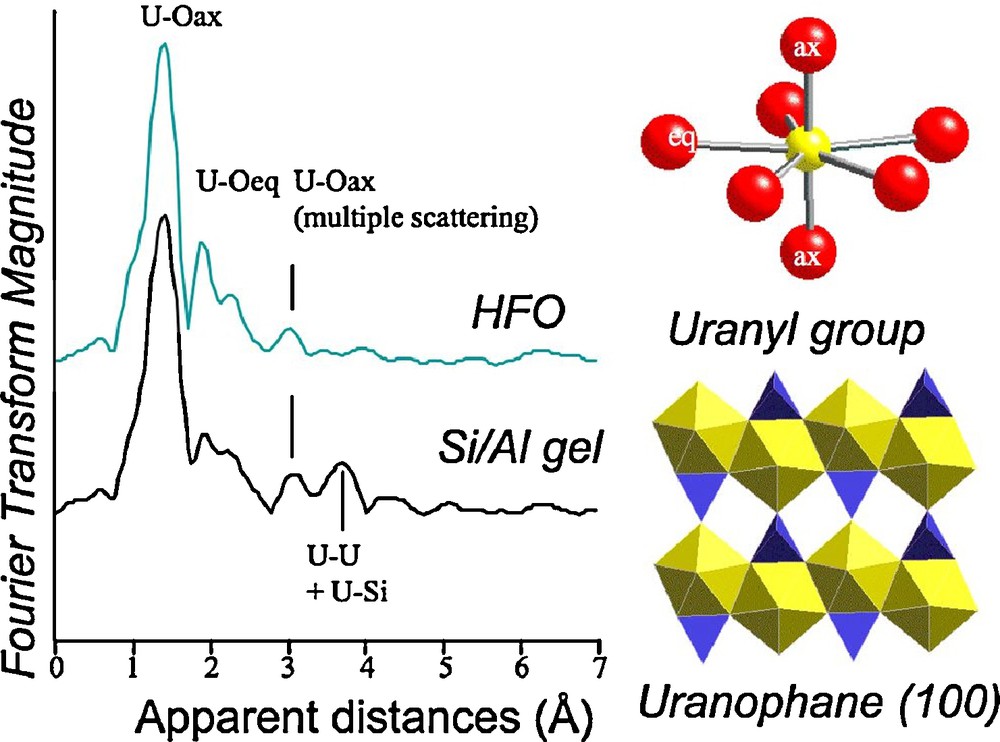

As the back end of the nuclear fuel cycle is discussed in this issue (Ewing, 2011; Libourel et al., 2011; Montel, 2011), we will only briefly discuss some questions concerning uranium mines and tailing sites, including the fate and transport of uranium in solution at low temperature and as nanoparticles and colloids. Uranium is a concern to humans because of its impact on ground water quality and the potential contamination by radioactive daughter elements (Ra, Rn…). Since the 1940s, uranium has been mined for nuclear power plants and nuclear weapons. The environmental and human health impact related to uranium mine tailings and disposal concepts (e.g., geological repositories) for High Level Nuclear Waste has been debated, because the drainage waters may export significant amounts of uranium and other radionuclides. Therefore, it is important to determine the natural uranium traps that help retard uranium transport. We will illustrate the environmental mineralogy of uranium through its sorption on minerals and gels, and the indirect tracing through the radiation-induced defects arising from its short-lived daughter elements.