1. Introduction

Global emissions of fossil CO2 were still rising in 2024, jeopardizing the chances of limiting climate change in the 1.5–2 °C range enshrined in the Paris climate agreement (Friedlingstein, O’Sullivan, et al., 2025; United Nations Environment Programme et al., 2025). However, the continued rise in global emissions masks progress in the underlying drivers of emissions at the national and regional level. Progress in tackling climate change has directly reduced the growth in global fossil CO2 emissions from its height of nearly 3% per year in the 2000s, to 0.7% per year in the past decade (2015–2024). The slower growth rate in recent years has been attributed to the success of public climate and energy policies, which accounted for emissions savings of 5.9 billion tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) in 2016 (Eskander and Fankhauser, 2020), reducing global emissions by 15% that year. Likewise, an estimate of avoided emissions from the deployment of renewable energy suggests 9.8 GtCO2 were avoided in 2024, reducing global emissions by 21% (Deng et al., 2025). Avoided emissions in turn led to avoided possible warming levels exceeding 5 °C this Century that were still plausible a decade ago (Friedlingstein, Andrew, et al., 2014). The slower growth in global CO2 emissions in the past decade is driven by changes in most large countries and regions, including China, India, and non-OECD countries in aggregate, where emissions grew more slowly, and the European Union (EU) and OECD countries in aggregate, where emissions decreased more rapidly. Emissions continued to decrease in the US in the past decade, but at a similar rate as the previous decade.

Notably, 22 upper-middle to high-income countries have succeeded in decreasing their fossil CO2 emissions significantly while also growing their economies, up from 18 countries a decade ago, representing 23% of world fossil CO2 emissions (Friedlingstein, O’Sullivan, et al., 2025; Le Quéré et al., 2019). In order to add up to changes substantial enough to reverse the rise in global fossil CO2 emissions, lessons learned during the progressive decarbonisation of these 22 countries would need to propagate rapidly to other countries. The sharing of insights is limited at present, as this group of leaders in the decarbonisation space has only expanded by four countries in a decade, while there are 38 countries in the OECD group of countries which are generally wealthy with well-developed physical and social infrastructures, and there are nearly 200 countries worldwide that will also need to decarbonise their energy systems eventually.

Three factors recur to explain decarbonisation trends in leading decarbonising countries (Le Quéré et al., 2019): First, these countries generally used decreasing energy levels either through efficiencies or absolute reductions in energy use. Second, the deployment of renewable energy in these countries replaced fossil energy, while in countries with emissions still rising, renewable energy often increased alongside fossil energy. Lastly, countries that had the largest number of climate and energy policies had bigger emissions cuts. This last point was evidenced by correlation only rather than causation, however the direct role of policy was later confirmed in a separate study (Eskander and Fankhauser, 2020). The switch from coal and oil to gas played a relatively minor role in most countries, apart from the USA.

Very few countries have succeeded in setting in motion economy-wide decarbonisation (Lamb, Grubb, et al., 2022; Lamb, Wiedmann, et al., 2021). The dominant factor of decarbonisation has been the move away from coal for electricity generation in the leading decarbonising countries, replaced mainly by renewable energy and to a lesser extent by gas. For example for the UK, which has cut its emissions in half since 1990, the switch from coal to renewables accounts for 79% of the country’s decrease in fossil CO2 emissions. Likewise in the EU in aggregate, the decrease in coal use in power generation accounts for 80% of the decrease in CO2 emissions, while in the US it accounts for more than 100%, as the other sectors increased their emissions while coal use reduced its emissions by 64%. However, many countries now face the challenges of decarbonising the whole economy. This is either because their electricity has historically been relatively low-carbon, such as France whose electricity is produced predominantly by nuclear reactors (share of 65–70%) and Canada where it is produced predominantly by hydroelectricity (60–65%), or because they have closed down all (as the UK) or most (as the USA) of the, often aging, coal-fired power stations.

Here I detail how France has succeeded in setting in motion its economy-wide decarbonisation and in maintaining decreases in CO2 emissions over two decades, from a baseline with relatively low coal use for electricity generation and hence relatively low per capita emissions (5.5 tCO2e/person in 2023) compared to other high-income economies and to the world average (6.5 tCO2e/person; HCC 2025). Consumption emissions from imported goods and services in France, although 1.7 times higher than territorial emissions (9.4 tCO2e/person in 2023), are also decreasing in parallel to territorial emissions since 2008 (HCC, 2025). This analysis is largely based on the progress reports of France’s High Council on Climate (HCC) and on CO2 emissions data collated by the Global Carbon Project’s annual Global Carbon Budget update and associated insights.

2. Decreases in emissions in France and in other decarbonising countries

2.1. Sustained decarbonisation in France for 20 years

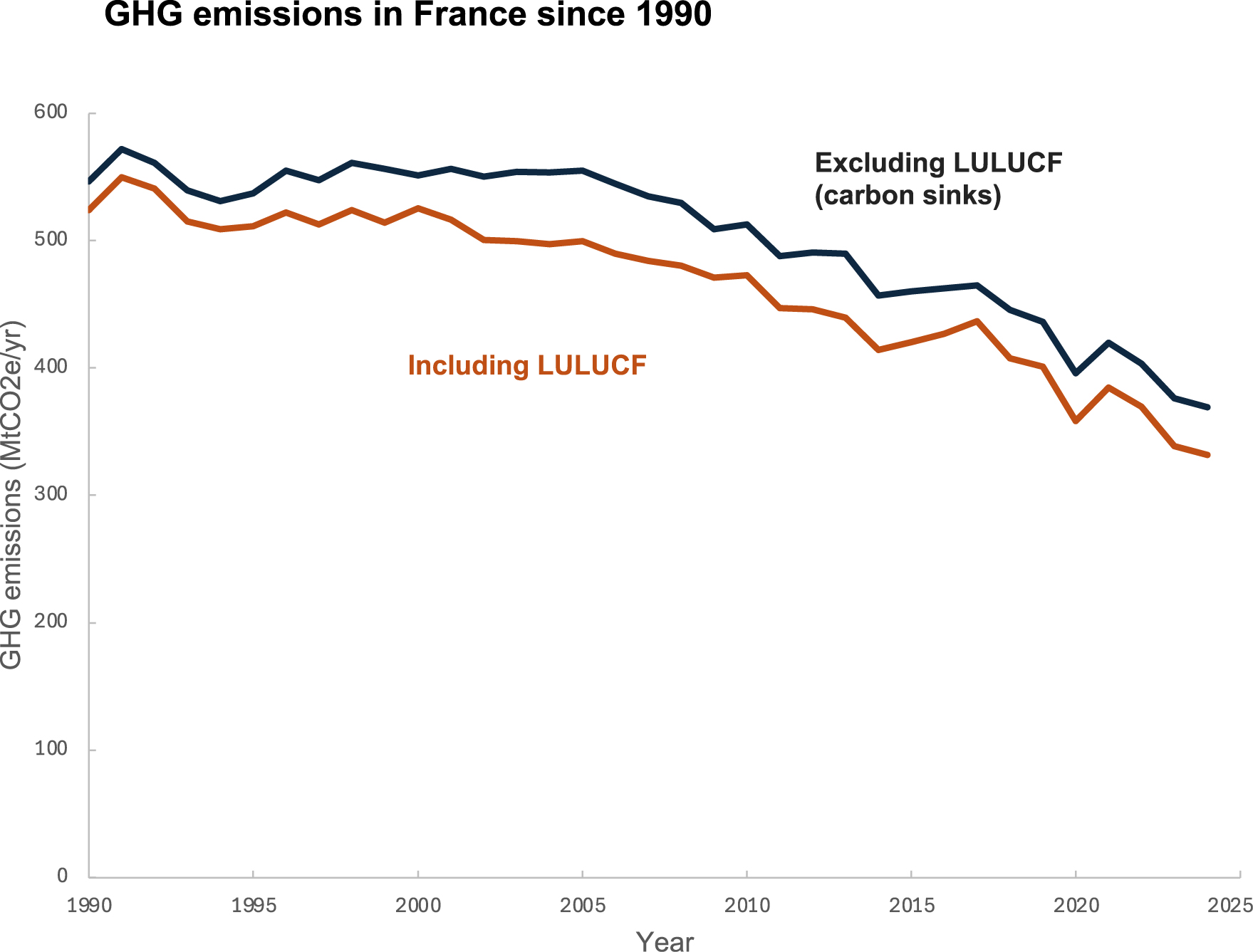

France’s GHG emissions began to decrease around 2005, as for many other countries. Its decarbonisation rate has been fairly constant, averaging 9.3 MtCO2e/year on average (−1.8%/year) during the decade 2005–2014 and 9.9 MtCO2e/year (−2.4%/year) during 2015–2024 (Figure 1; trends calculated as linear fit through 2004–2014). These rates are comparable at 7.9 MtCO2e/year (−1.7%/year) and 9.7 MtCO2e/year (−2.5%/year) when including the CO2 sinks from the land sector (LULUCF) for each decade, respectively. This decarbonisation pathway has been maintained for 20 years, with emissions at 369 MtCO2e in 2024 (332 MtCO2e including LULUCF). The last few years since 2019 have shown some signs of acceleration up to 2024, backed by enhanced policy support, but this acceleration needs policy continuity at the French and European level to be maintained (HCC, 2024b).

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in France during 1990–2024 in million tonnes of equivalent CO2 per year (MtCO2e/year). Emissions are shown for all GHG and emitting sectors in France, excluding (in black) or including (in brown) the carbon sink from the land use, land use change and forestry sector (LULUCF). Source: Citepa (2025).

2.2. Sustained decarbonisation in 22 countries, with France in the middle

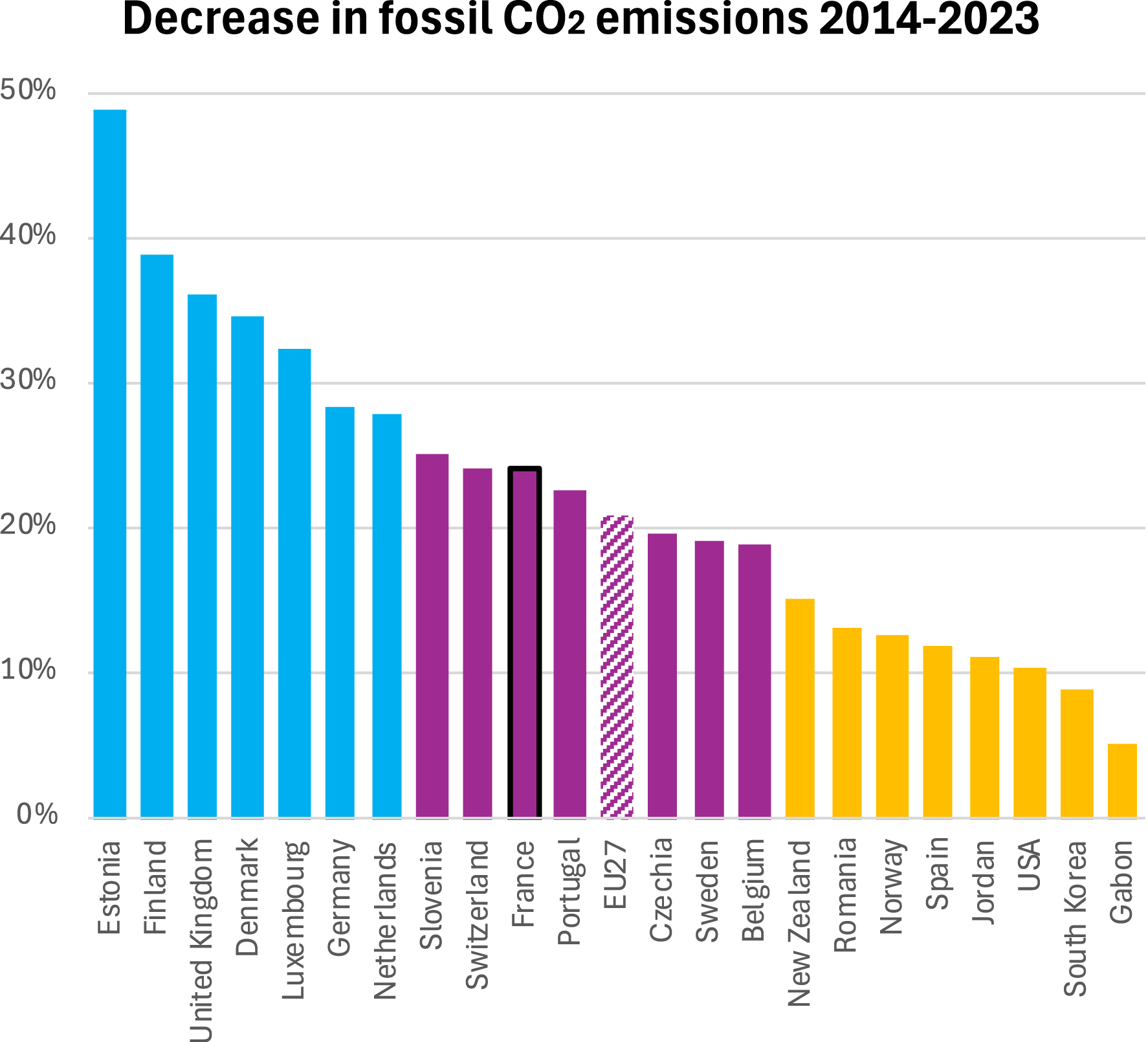

The rate of decarbonisation in France sits close to the middle of the countries that have decarbonised their economy in the decade 2014–2023, just above the rate observed over the EU in aggregate (Figure 2). These are compared for their fossil CO2 emissions only (including fossil fuels and process emissions such as cement), which are available for all countries up to the year 2023 through the Global Carbon Budget annual emissions update (Friedlingstein, O’Sullivan, et al., 2025). This group contains the 22 upper-middle to high-income countries that have statistically significant decarbonisation of their fossil CO2 emissions while also having statistically significant increases in their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Of that group of 22 countries, five countries have decarbonised at notably faster rates of 3% per year on average, while some countries like the US decarbonise consistently but slowly around a rate of 1% per year. Somalia also decreased its emissions while growing its GDP, but it is excluded from the comparison here because it is low-income and not comparable to other countries in that group.

Decrease in CO2 emissions of fossil origin during the decade 2014–2023 (in percent). The 22 countries are subdivided in three groups for comparison in the text. EU27 in aggregate is also shown. France is highlighted with a black contour.

2.3. CO2 emissions decreases among countries uncorrelated to GDP growth in the past decade

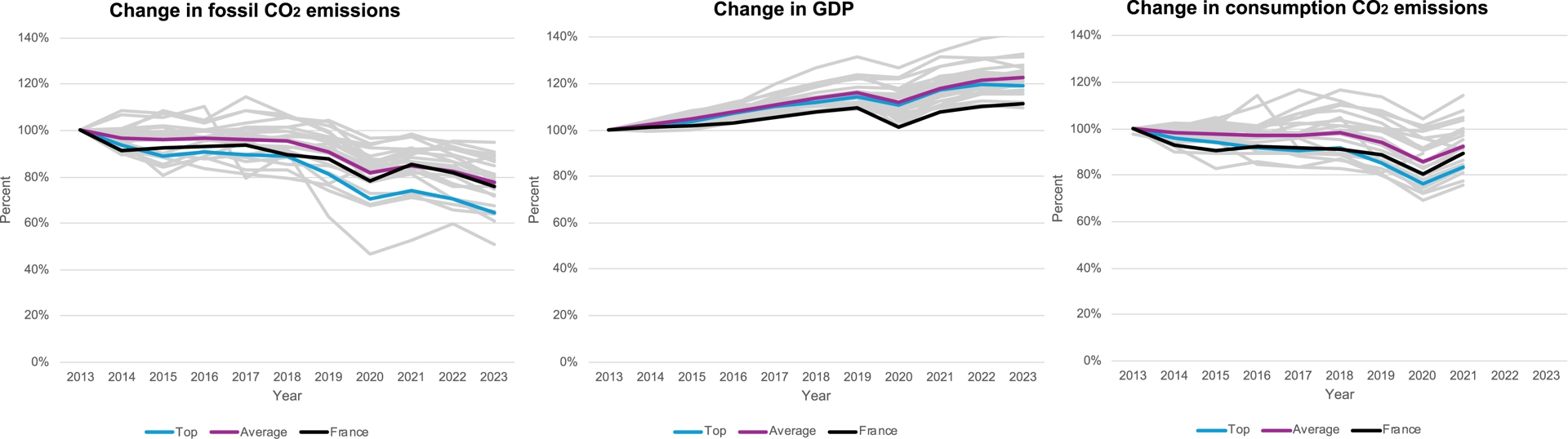

Fossil CO2 emissions decreased 24% in France in the decade 2014–2023 while its economy grew 11% (Figure 3). While weak economic growth can temporarily reduce energy demand and associated emissions, long-term decarbonisation trends need to decouple from long-term economic growth to enable economies to flourish while tackling climate change. There is no significant correlation between the decrease in emissions and growth in GDP among the 22 leading decarbonisation countries (r = 0.30, p = 0.18), indicating at a minimum that weaker growth in GDP does not account for stronger decarbonisation trends, and conversely that strong decarbonisation trends can be delivered in the presence of strong economic growth. Among the seven countries that decarbonised the fastest (top third; Figure 2), GDP grew by 20% or more over a decade in Denmark, Estonia, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, and between 10% and 20% in the UK, Finland, and Germany. The average GDP growth among these seven countries (19%) is very close to the GDP growth of all 22 countries (22%), also demonstrating the low relevance of GDP growth in setting decarbonisation trends among those countries.

Change emissions and GDP in the past decade (2014–2023; percent). (left) Fossil CO2 emissions, (middle) GDP, and (right) CO2 emissions estimated based on consumption accounting. Values are referenced at 100% in 2013. France is shown in black, the average of the 22 decarbonising countries in purple, and the average of the seven countries decarbonising the fastest in blue. Data is from the Global Carbon Budget 2024 (Friedlingstein, O’Sullivan, et al., 2025) using GDP based on Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). No data for consumption emissions is available for Gabon.

2.4. CO2 emissions on a consumption-basis also decrease in parallel to territorial emissions when accounting for the origin of imports

In some cases, decreases in emissions can be indicative of changes in economic structure, leading to leakages of emissions in other countries, rather than true decarbonisation of the economy. Consumption-based emissions include emissions associated with imports of goods and services produced in other countries for consumption in a given country, minus the exports (also called “carbon footprint”). In contrast, territorial-based emissions used widely, including here and by the UN as a basis for a country’s climate objectives, occur on the national territory. Consumption-based emissions provide one measure to test for the possible importance of leakages. However, for countries that decarbonise, it is expected that trends in consumption emissions will be less than trends in territorial emissions if part of their imports come from countries where emissions still grow, such as most emerging economies including China and India. Hence lower decreases in consumption-based emissions do not necessarily mean a lack of progress or leakage of emissions elsewhere as it can also be indicative of lags in decarbonisation profiles among countries.

For example, half of France’s consumption-based emissions comes from imports, a fraction that has remained relatively constant for the past two decades (HCC, 2023a). Of those imported emissions, about 30% come from the EU, the UK and the USA who have decarbonising profiles somewhat similar to France (Figure 2), about 35% come from China and other Asian countries, while the remaining ∼35% is distributed among other countries (the Middle East, Russia, Africa, South America) (HCC, 2020). If imports remain the same and the emissions trends typical of these regions are applied to their respective fractions of imports, the expected decrease in consumption emissions for France corresponding to the decrease in territorial emissions of −24% during 2014–2023 would be −11%, so less than half. Likewise, a country whose consumption emissions remain flat while its territorial emissions decrease does not mean a lack of progress, because part of the difference will certainly reflect growing emissions in the imported fraction offsetting decarbonisation at the national level.

The decrease in territorial CO2 emissions in France parallels the decrease in consumption emissions over the 2013–2021 period, when data were available (Figure 3). Territorial CO2 emissions decreased 15% during this time period, while consumption CO2 emissions decreased 11%. The different rates here can be accounted for by a slower decarbonisation profile in countries where imports originate. Among the 21 decarbonising countries, there is a significant correlation of r = 0.66 between trends in consumption and trends in territorial emissions, indicating that countries that decarbonise the most do it both on consumption and on a territorial basis, with the consumption trends on average 68% of the territorial trends (based on linear regression). Five countries decarbonise on a territorial basis but not on a consumption basis at this stage (Czechia, New Zealand, Romania, Slovenia, and South Korea), but in all but one country (Slovenia) the different decarbonisation rates between territorial and consumption-based emissions are 10% or less and can be partly explained by the emissions profiles in countries where imports originate. Slovenia’s large difference between the trends in territorial (−14%) and consumption-based emissions (+15%) is the only country of the group examined here where the leakage might explain the decarbonisation, and further investigation would be needed to find out.

The analysis above for both territorial and consumption-based emissions suggests that for all countries but one, a strong case can be made that real progress is taking place in decarbonising the economies of a leading group of 21 countries (excluding Slovenia), five of which have achieved decarbonisation rates exceeding 3% per year sustained for at least one decade (2014–2023). Over the same period, France’s decarbonisation rate of 2.4% per year on average (for fossil CO2 only) has been achieved by spreading decarbonisation efforts across the economy. Its climate policy framework and sectoral emissions profile are presented in sections below to extract insights that may be useful more broadly.

3. France’s climate policy

3.1. Evolving climate policy within the EU framework

The summary provided here gives a brief overview of the organisation of climate action in France’s public sector. It does not aim to be comprehensive, but rather to give insights into the level of ambition, and into the successes and failures of successive attempts to organise climate action. This information is necessary to understand how France has been able to establish economy-wide decarbonisation over two decades, and to argue that it has done so successfully but imperfectly.

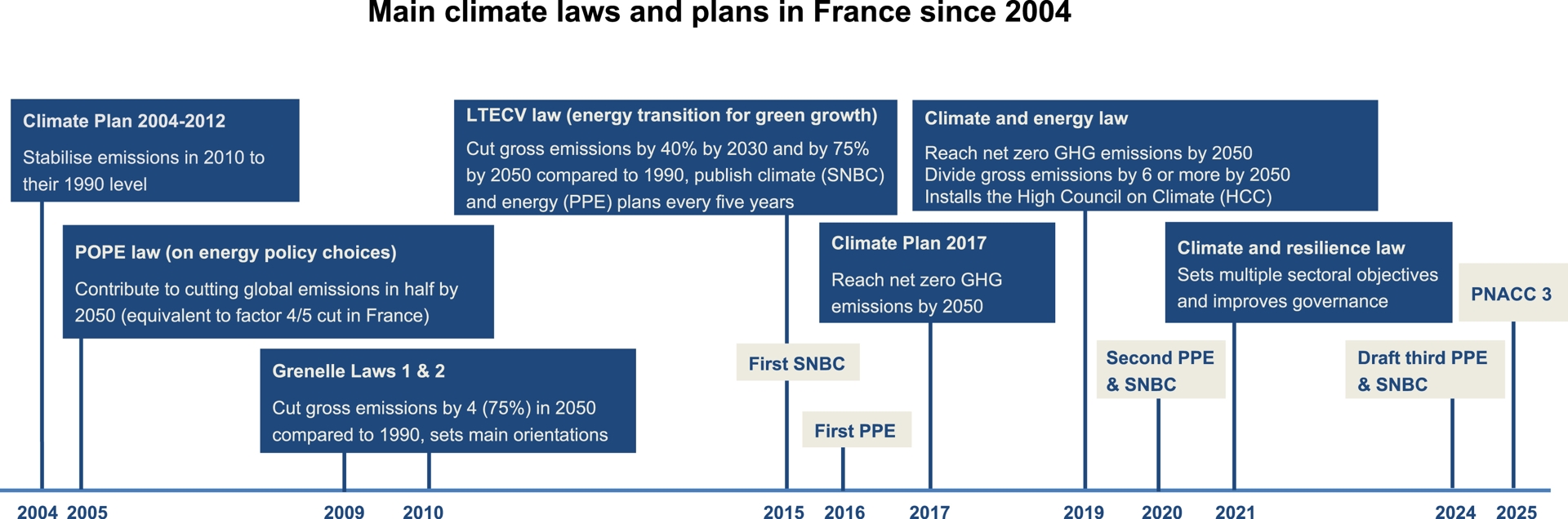

National climate policies in France have been revised iteratively on multiple occasions. Climate policies have been in place since at least 2004 with the publication of a Climate Plan (Figure 4). The plan turned into a programmatic law in 2005 that established the main orientations for the energy sector for France (the POPE law). Plans and laws have been revised iteratively on multiple occasions, with the LTECV (energy transition for green growth law) of 2015 prescribing a 5-year process that included revisions of a National Low-Carbon Strategy (SNBC) and a Pluriannual Energy Program (PPE), and the associated publications of carbon budget objectives limiting France’s GHG emissions in successive 5-year periods, 10 years ahead of time. The long-term climate objective for France has converged on achieving net zero in 2050 including all GHG, which was set in law within the Climate and Energy law of 2019. This law also announced a ceiling for International aviation and shipping and for consumption-based emissions to be published within the third revision of the SNBC (SNBC3, currently in draft form). Plans and laws have been accompanied by an increasingly detailed set of sectoral objectives and implementation rules that have provided additional visibility to climate legislations but not necessarily clear orientations, with sectoral objectives often set below what was needed to reach national climate objectives (HCC, 2021).

Main climate laws and plans in France since 2004. Reproduced and updated from HCC (2019). See text for the definition of acronyms.

Climate policy in France and the EU are closely intertwined, for the benefit of both. France benefits from a strong and clear climate policy framework in the EU, most recently set by the European Climate Law of 2021 and detailed in the Green Deal overarching policy and Fit for 55 detailed policy package. France was a central contributor to fleshing out these policies, particularly while it held the EU presidency during the first half of 2022. France also benefits from the European Trading Scheme (ETS) which is instrumental in reducing energy and industry-related emissions in the EU. Despite the strong EU framework on climate change, France has struggled to keep up with the required implementation of regulations decided jointly by France and other State members at the EU level. For example, France’s 2030 target set at the EU level has not yet been translated into a national legal objective, reducing clarity over the actual objective for 2030, which is only 5 years away. Likewise, the EU-wide standard for cars and vans is not in the French legislation, causing some ambiguity about the needed level of action in France.

3.2. Evolving climate governance and democratic instruments

France has put in place multiple democratic instruments to help guide its climate policy. A long-standing organisation is the National Council for Ecological Transition (CNTE), which evolved from the committee established in 2010 to follow the Grenelle laws. The CNTE brings together public and non-public organisations (including Parliamentarians, unions, NGOs, and regional representatives) to give advice on environmental and energy strategies. It is a solid organisation of 58 members which is core to achieving national consensus on climate action. Arguably the most influential instrument in recent years has been the Citizen’s Climate Convention (CCC). Established in 2019 to get citizens’ help to accelerate climate actions, it brought together 150 randomly selected citizens during a 9-month period. Citizens were formed to climate change challenges and asked to propose solutions. Their 150 solutions served as a basis for the 2021 Climate and Resilience law. Other instruments included the short-lived Ecological Defense Council (2019–2020) that reunited the President, Prime Minister and 10 Ministers to address climate and environmental issues, and the National Council for Refoundation that aimed to concert more effectively on major challenges including climate change.

France’s governance has regularly been adjusted to manage its climate ambition. It established a General Secretariat for the Ecological Planification (SGPE) in 2022 to coordinate and implement France’s strategy for climate, energy, biodiversity and the circular economy. This secretariat is under the responsibility of the Prime Minister, hence benefiting from the highest level of governmental support. Since its onset, it has greatly contributed to clarifying how France aims to achieve its climate objectives, thus improving the cohesion within government on climate action and helping to engage businesses and industry in the transition. Notably, the Ministry of the Economy and Finances has founded a sub-direction focused on how to finance the ecological transition, and has committed to increasingly use the Green Budget approach (OECD, 2024) to orient spending towards climate-favourable actions and away from fossil fuels.

France has also established an independent body, the High Council on Climate (HCC), whose role is to evaluate public action on climate. The HCC has published seven annual progress reports on climate action and several thematic reports, including on consumption-based emissions (HCC, 2020), the Energy Charter Treaty (HCC, 2022), CCS (HCC, 2023b), and agriculture and food systems (HCC, 2024a). The government responded to each progress report and, according to the HCC’s analysis, most recommendations have been taken into account, at least partially (HCC, 2024a; HCC, 2024b). Much of the analysis presented here is drawn from the HCC’s successive reports.

4. France’s sectoral emissions and their evolution in time

4.1. GHG emissions in France are distributed across the economy, with transport the first emitting post

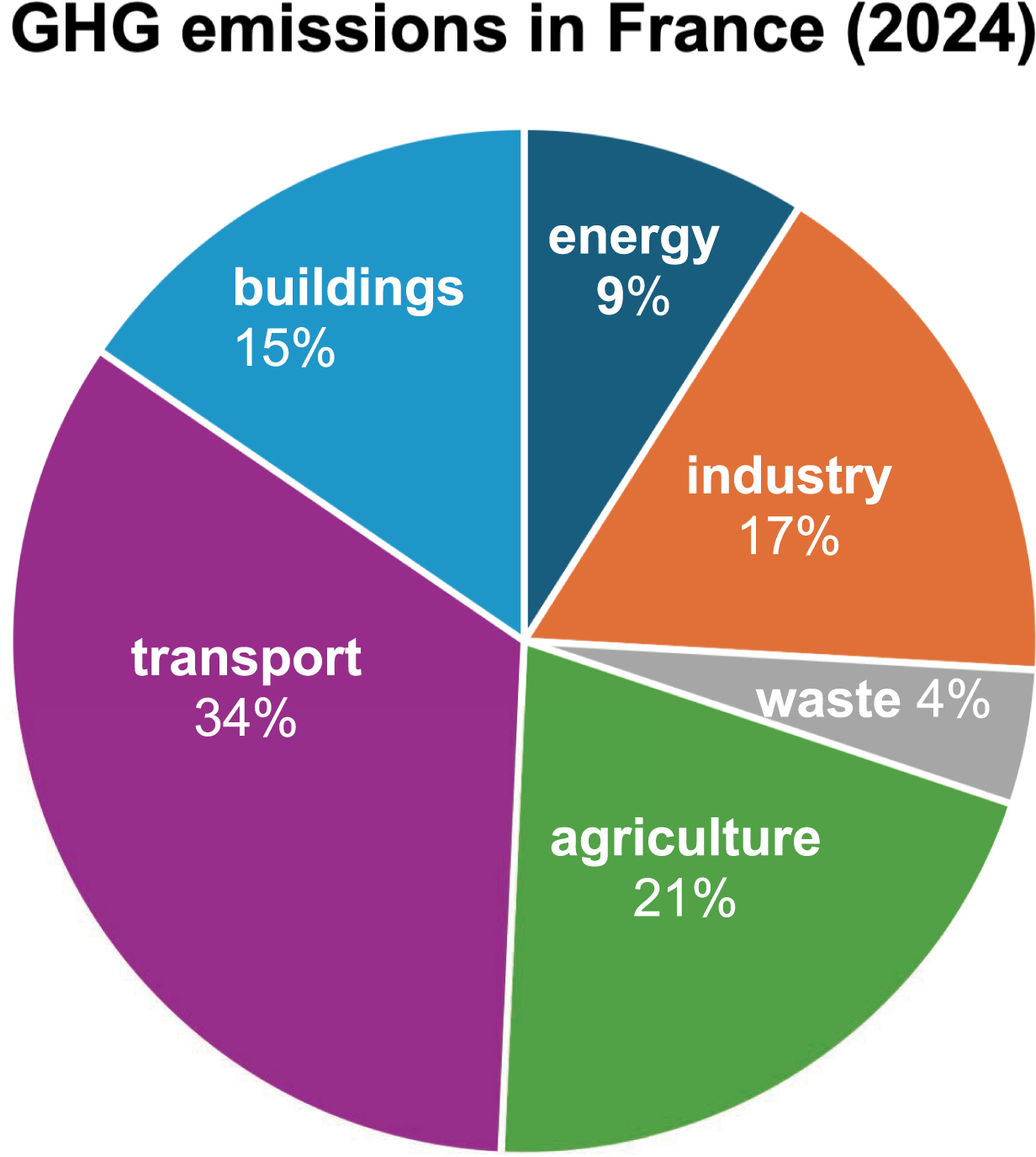

France’s electricity has been predominantly generated by nuclear power since the mid-1980s, after a conscious effort to reduce exposure to volatile energy prices following the 1973 oil crisis. Emissions from electricity generation were only 10% of total emissions in 1990, and have come down to 3% in 2024 (10 MtCO2e). Although there is still some scope to reduce this contribution to zero or very nearly, profound cuts in national emissions need to come from other sectors. Emissions in France in 2024 were distributed across the economy, with 34% from transport (more than half from cars alone), 21% from agriculture, 17% from industry, 15% from buildings, 9% for energy (including electricity, refineries, heat networks), and 4% from waste (Figure 5). Proportionally in the past decade, buildings, energy and to a lesser extent the industry sectors have reduced their relative contribution to national emissions, while the transport, agriculture and waste sectors have increased their relative contribution. France also has a substantial forestry sector and large carbon sinks, which offset around 10% of the gross emissions.

Distribution of GHG emissions in France among sectors in 2024. Source: Citepa (2025) « Rapport Secten ».

4.2. GHG emissions in France have decreased in all sectors but the carbon sinks have deteriorated

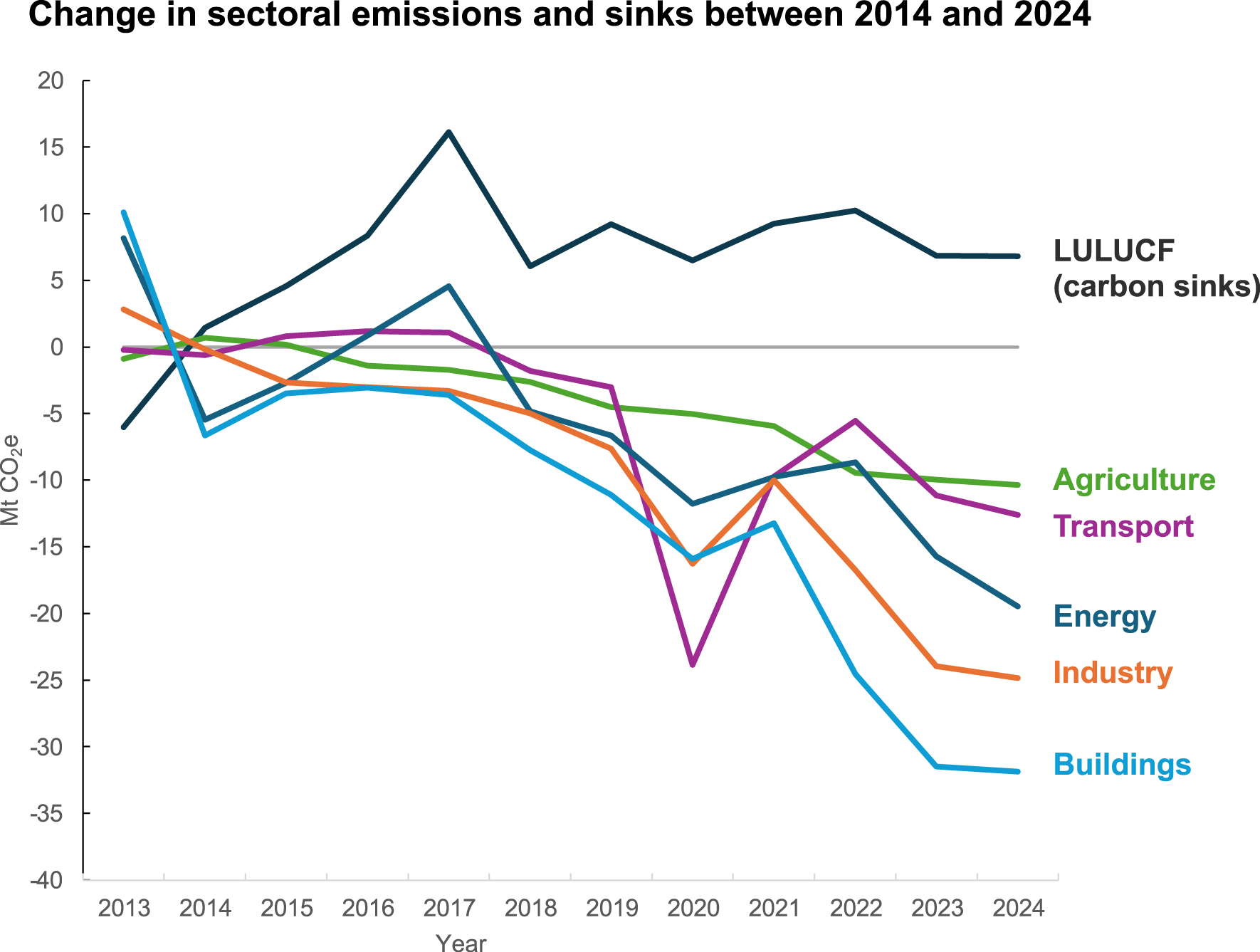

GHG emissions have decreased by 100 MtCO2e (−21%; period of 2024 compared to the 2013–2025 average; Figure 6; data: Citepa (2025)). During that period, GHG emissions have decreased in all sectors (Figure 6), with only the storage in carbon sinks diminishing. Identifying the contributions of public policy to these decreases is important to guide further action. Whereas a detailed attribution cannot be made within the scope of this paper, some indication is provided here of the likely policy and non-policy factors that have most influenced sectoral emissions trajectories over the past decade. Detailed attribution to policy would require a formal analysis with counterfactuals, such as that identifying successful policy mixes covering EU road transports (Koch et al., 2022), and the analysis of the role of carbon pricing in power sector decarbonisation in the UK (Leroutier, 2022).

Change in sectoral GHG emissions and in the carbon sinks in France in the past decade (MtCO2e). Positive values in LULUCF indicate weaker carbon sinks. The 2013–2015 average is used as reference to limit border effects. Source: Citepa (2025) « Rapport Secten ».

Emissions in the transport sector decreased 13 MtCO2e (−9.2%) only in the past decade (2024 relative to 2014). This sector has been notoriously difficult to decarbonise prior to the availability of electric vehicles, as improvements in vehicle efficiencies have been to a large extent offset by an increase in vehicle size in the recent past. A lot of effort has been put in France and in the EU to support the production and purchase of electric vehicles. Efforts in France have included a “bonus-malus” policies with heavy petrol and diesel vehicles taxed more with funding redirected towards smaller and low-emissions vehicles, an EV leasing scheme to help low-income households, EV quotas were put on vehicle fleet of larger businesses, and support was provided for the deployment of electric charging points. In the short-term, the electrification of vehicles can only account for around 3 MtCO2e (20%) of the decarbonisation of the sector so far (estimated here based on emissions substitution at constant demand level). Other factors include possible restructuration of working patterns post-COVID reducing transport demand, and an economic downturn reducing transport demand of heavy goods vehicles (HGVs). Nevertheless, the assessment of the HCC is that the main surface transport sub-sectors (cars, vans and HGVs) have all begun to decarbonise their fleet by electrifying their vehicles, even though other levers influencing miles traveled have not been identified and/or mobilised substantially so far (HCC, 2024a; HCC, 2024b). There is an important potential to go further and faster in this sector by leveraging further existing policies (HCC, 2025).

Emissions from agriculture decreased 10 MtCO2e (−12%) in the past decade. About one third of this decrease comes from decreases associated with reduced use of fertilisers. Policies and incentives at the national and European levels will have helped to drive this change, but the pressure of inflation raising the costs of fertilisers also played a role. The largest share of emissions reductions in this sector comes from reduced animal farming resulting from economic difficulties external to climate policy (HCC, 2024a). Climate policies themselves are thought to be little effective in this sub-sector, because they suffer from the lack of integration with food, agriculture, and environment policies, leading to a situation where climate policies put on farmers are faced with blockages from intermediate actors of the food system (including the food industry, distribution, and restauration) where inertia favours emissions-intensive foods to the detriment of low-carbon and healthy production and consumption offer (ibid.). Given the sector is particularly exposed to climate impacts, a systemic approach is needed to protect and support agricultural communities within a framework that also decreases its emissions. Agroecological practices can help to reconcile production with reduced emissions and carbon storage (HCC, 2024a; HCC, 2024b) within a broader food-systems approach. Current policy developments in response to difficulties in the sector are working to slow down decarbonisation and the adaptation actions needed to increase the resilience of the sector to climate impacts (HCC, 2025).

Emissions from industry decreased 25 MtCO2e (−28%) in the past decade. All eight industry sub-sectors contributed to this decrease. Over the past decade, the structure of the economy can account for a decrease in emissions of 10% (HCC, 2024a; HCC, 2024b), so just under one third of the total decrease of the sector. Hence the majority of the decrease in emissions can be attributed to meaningful factors, including energy and material efficiencies incentivised by the ETS and other policies supporting the use of electricity or low carbon heat. Generally high costs of energy in recent years will also have led to savings and efficiency. France has put in place roadmaps to decarbonise industry sub-sectors, which have been co-constructed with relevant industry actors. It has also put in place contracts to decarbonise the four sub-sectors and the 50 most polluting sites in France with the objective of reducing industry emissions at least 45% from 1990 level by 2030. France also launched a “Sufficiency Plan” in 2022 (“Plan de sobriété”), aimed at reducing energy use and waste, which included many structural measures to encourage and promote reduced energy use in industry. Emissions from the waste sector, in contrast, have barely decreased in the past decade (0.5 MtCO2e; −3.3%).

Emissions from buildings decreased 32 MtCO2e (−36%) in the past decade. Reductions took place in both residential and non-residential buildings. Emissions in that sector overwhelmingly originate from heating. Government policies have provided a lot of support to decarbonise heating, leveraging in particular post-COVID economic stimulus to boost financial support over multiple years. Public support has been successful in substituting oil and gas boilers for electric heat pumps, leading to 1 million heat pumps installed every year since 2020. Regulations have also been enacted on energy standards in new buildings. The government’s Sufficiency Plan also provided incentives to reduce energy demand in buildings through infrastructure adjustments and guidance on ambient temperature and other low-energy practices. Support for energy efficiency measures (such as insulation) has been less substantial and stable, with multiple changes in regulations and funding that have reduced clarity for the industry and consumers. Energy efficiency measures are thought to be essential to reduce total electricity demand and reach net zero emissions by 2050 (HCC, 2024b). Reduced winter heating demand due to a warming climate can account for approximately 4 MtCO2e of the decrease in emissions in the past decade only (based on the correlation between heating degree days (HDD) and building emissions, and IEA data (IEA, 2022)).

Emissions from the energy sector decreased 19 MtCO2e (−37%) in the past decade. This sector continues to decarbonise, supported by national and European policies to reduce the use of coal for electricity and to gradually develop low-carbon or electric urban heat networks. France has announced the end of coal use in power for a long time, but is facing difficulties in materialising this commitment both because of the lack of suitable preparation to deal with peak electricity demand during winter and from just transition difficulties that come with industry closures. However the primary challenge for reducing the sector’s emissions at this point is to mitigate gas use in electricity production. More broadly, the sector needs to expand low-carbon electricity generation to support the electrification and decarbonisation of the other sectors. Recent governments have committed to expanding nuclear power production, but new nuclear reactors take time to build (typically 10–15 years) and come with high uncertainties on costs and delivery time scales. As a result of this strategy, France faces a shortage of low-carbon electricity generation in the medium term (5–15 years) unless it greatly expands its renewable energy deployments and associated network infrastructure (HCC, 2024b). The energy sector is also influenced by reduced winter heating demand due to a warming climate, which can account for approximately 3 MtCO2e of the decrease in emissions in the past decade in that sector (see details above).

Carbon sinks from the LULUCF sector decreased 7 MtCO2e (−15%) in the past decade. This was caused by important tree mortality in forests between approximately 2013 and 2017, in response to successive droughts made worse by climate change that have favoured insect outbreaks (such as beetles). There is an increasing recognition in France that forest regeneration needs to scale up to support ecosystems and the forest-based industry. For example, France held the “Assises de la forêt”, a sort of emergency gathering of actors during 2021–2022 that aimed to bring to the fore the urgent needs of the sector and identify actions that can be taken forward. Although many actions are in progress, an overall vision has not yet emerged that would guarantee the regeneration of the aging forest in a context of a changing climate, with growing needs for biomass also for carbon storage and energy uses. In parallel, France has recognised the importance of land use changes and put in place measures to limit soil artificialisation (i.e. the conversion from forest or pastures to artificial surfaces or cropland). These policies are faced with obstacles as they interfere with development and planning, but the topics are very high on agendas and the climate implications of land use change are being discussed actively.

5. Likelihood of France meeting its 2030 and 2050 climate objectives

The recent rate of decarbonisation during 2019–2024 (−3.4 MtCO2e per year on average, excluding carbon sinks), was below what is needed to meet France’s 2030 target (between −16.0 MtCO2e per year during 2025–2030 on average). Emissions decreased less in 2024 (−6.9 MtCO2e) comparatively. The sections below assess if the framework in place is sufficient to support continued decarbonisation of the level required up to 2030, and if the long-term challenges to achieving net zero in 2050 are being tackled.

5.1. A climate policy framework in place that needs consolidation

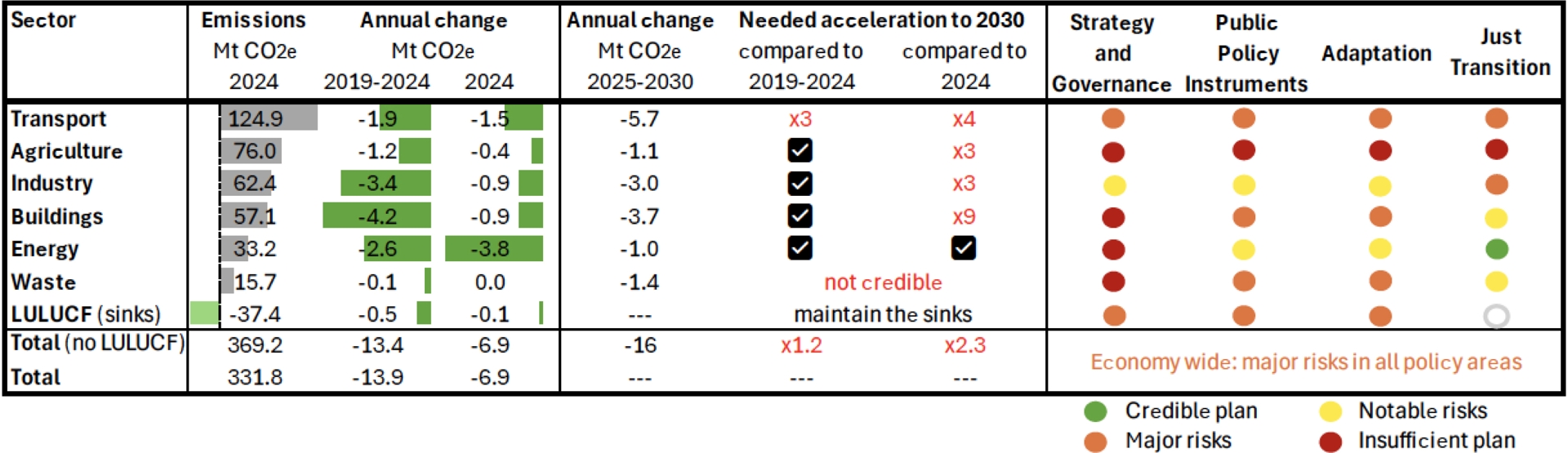

The analysis in this section summarises the 2024 policy assessment of the High Council on Climate (HCC, 2024b), and comments on difficulties encountered in the past year that have blocked and sometimes reversed further progress (HCC, 2025). The HCC set up an evaluation framework to assess France’s climate action which now includes four elements that are scrutinised and evaluated for each sector (Table 1).

Emissions and policy progress by sector

|

Emissions are shown by sector for all GHG for the last year available (2024), with the mean change over 2019–2024 and for the year 2024 alone, compared to the rate needed over the 2025–2030 period to meet France’s 2030 target. Policy progress is assessed by the HCC by sector for four areas based on evidence up to spring 2025 (HCC, 2025). Table adapted and updated from HCC (2024b) and HCC (2025).

- Governance and Strategy. The overall governance and strategy of climate action in France has been functional and operational so far, with an overarching framework (SNBC, PPE, and adaptation plans) and sectoral climate plans on how to decarbonise in place. However, difficulties have been met to maintain good governance and clear strategy in the long term. First, important delays have occurred in revising the plans, which should be updated every five years, in particular following the strengthening of objectives agreed at the EU level and the recent politicisation of climate action worldwide. Second, the level of ambition within sectoral plans often doesn’t match either the level of ambition of the overall target or the level of ambition written in different laws (HCC, 2021). Furthermore, setbacks in several policy instruments in 2024 and early 2025 reduced visibility for public and private actors (HCC, 2025). The strategy is thought to be most suitable for the industry sector, with action plans for most industries in place, and committed financial support to decarbonise the 50 most polluting sites co-developed with the stakeholders.

- Public Policy Instruments. Strategies and action plans must be accompanied by public policy that are able to trigger changes to the right levels and maintain them over time. Public policy will determine the relative contributions of the public and private sectors in the transition, the co-benefits, and will have implications for treasury, households, businesses, jobs, and the commercial and industrial policy of the country. Most sectors in France benefit from incentives for action at this stage, but incentives are not all sufficient to trigger the right level of change, particularly in the long-term. In particular, long-term visibility on public financial support has been fragile, reducing confidence and limiting investments. Still, major efforts have been made in France to align national decisions with the transition towards net zero, for example with aspects of the stated reindustrialisation and with forest management.

- Adaptation. Mitigation in some sectors will only be possible with integrated adaptation efforts. This is mentioned as an ambition in the draft SNBC3. The publication of the third National Adaptation Plan (PNACC) in March 2025 based on an agreed reference warming trajectory is a major step forward to guide adaptation decisions. Adaptation needs are notably acknowledged for energy, where the nuclear industry in particular takes into account a warming climate within its planification. For other sectors, important risks persist, which are particularly problematic in the LULUCF sector given the recent deterioration of carbon sinks related to tree mortality made worse by climate change. Adaptation is poorly anticipated in the agricultural sector, which is already suffering important impacts from weather extremes made worse by climate change.

- Just Transition. Efforts have been made to take into account the different aspects of a just transition in climate policy, and some actions of the SNBC have a specific emphasis on reducing impacts on vulnerable people. However, a much more systematic effort is needed to make low-carbon choices accessible and desirable to the majority of the population and to support households and businesses that will be most affected by the necessary actions to tackle climate change.

In addition to the policy areas above, many very practical barriers can slow down climate actions, such as the availability of physical infrastructure such as affordable electric vehicles and charging points and supply chains, and social and economic organisation, such as skills, public support, planning and procurement, and research. Most of the barriers and enablers have been identified in the various strategic documents published by the French government (HCC, 2024b). In particular skills come out as limiting across sectors but particularly for buildings, energy and agriculture. Barriers in the transport sector are better anticipated than elsewhere, with a good rate of deployment for charging stations and efforts to move markets towards an offer based on smaller, more affordable cars.

The public policy framework in France has constantly evolved over the past two decades. Most evolutions have been towards a strengthening of climate actions, with increased planning details and funding, and more engagement with stakeholders. Despite the numerous issues identified by the HCC and others, it is clear that successive French governments so far have internalised the need to tackle climate change, with the strength of public efforts heavily influenced by other priorities. The setback of some public climate policy support in 2024–2025 reduces the likelihood that France meets its 2030 target, but it needs to be put in the longer-term context of growing efforts and successful decarbonisation across sectors in the past decade (Figure 6), even though the pace is not as fast as it needs to be (Table 1).

5.2. Meeting 2030 target is plausible for France

Achieving France’s 2030 target of cutting its gross emissions in half compared to 1990 requires that the level of decarbonisation observed over 2019–2024 be enhanced by 20% on average during 2025–2030 (Table 1). The fact that most sectors are already engaged in climate actions and that plans are in place suggests that this is plausible (ibid.). However, the weaker decreases in emissions in 2024 (Table 1) and the policy setbacks in 2024–2025 are threatening the credibility of the 2030 target, unless the government reacts quickly to consolidate and enhance climate policy support (HCC, 2025). Most sectors have reached the level of sustained emissions decrease needed to meet the 2030 objective, with the energy sector outperforming on expectations (Table 1). However transport, the biggest emitting sector, is a long way behind its objective. Although electrification of vehicles in France has picked up more than in other neighbouring countries (e.g. Germany, and to a lesser extent the UK), the 2030 objectives can only be achieved with increased efficiency and reduced demand in addition to the electrification of vehicles, as acknowledged in the draft SNBC3. A rebalancing of efforts among sectors is needed to recognise the difficulties faced by the transport sector in the short-term to 2030. The strong and unexpected budget deficit that emerged in France in mid-2024, resulted in additional uncertainty and reduced funding for climate action, both of which will reduce the investments necessary to decarbonise the economy in the long-term, with likely short-term effect as well.

5.3. Meeting net zero in 2050 will require better alignment of actions

Achieving France’s 2050 net zero target requires strategic plans that go beyond the continuation and consolidation of ongoing actions. The current strategy does not provide sufficient coherence with the needed investments to reach net zero (HCC, 2024b). This is particularly the case in the LULUCF sector with the uncertainty surrounding the efficiency of forest carbon sinks in the context of a changing climate, in agriculture where policies need to join up between agriculture, food and health, and in buildings where policies need to embrace energy efficiency more strongly in order to reduce the need for rapid expansion of electricity generation. Difficulties in finding a pathway to 2050 recognised in the draft SNBC3 acknowledges existing inconsistencies between the needs for electricity generation and energy demand, and the residual gross emissions and the availability of carbon sinks (natural and technological). These inconsistencies will need to be resolved within existing uncertainties, keeping multiple options open in cases where an optimal cost-effective pathway cannot be found.

The experience of the UK Climate Change Committee (CCC), which advises on carbon budget levels in addition to evaluating progress, is that identifying a realistic path to net zero requires dealing with important uncertainties regarding the availability of low-carbon fuels and removal technologies (CCC, 2025a; CCC, 2025b). These options are needed to decarbonise sectors that cannot be electrified at scale (mainly aviation, agriculture, and some process emissions). Hence choosing between low-carbon fuels, removals, and/or demand management to decarbonise difficult sectors will only be possible as technologies develop and their limitations and costs become clear. The CCC also found that net zero emissions could be achieved within the land sector (agriculture and carbon sinks from LULUCF) independently of the wider economy. This opens up opportunities to design targeted policy incentives for landowners to manage their carbon balance and help reach net zero in the combined land sectors. Finally, in its advice for the level of the UK 7th Carbon Budget covering the 5-year period around 2040 (CCC, 2025a; CCC, 2025b), the CCC established that its pathway should be limited to 87% of 1990 emissions levels (90% when excluding emissions from international shipping and aviation). The UK has cut its emissions by 50% between 1990 and 2024 (CCC, 2025a; CCC, 2025b), compared to 37% for France (based on Citepa (2025), Secten data, including LULUCF) and the EU (year 2023; (European Commission, 2024)). Hence achieving a 90% decrease in emissions in the EU by 2040, proposed by the European Commission, would require measures that go much beyond those included in the CCC advice (CCC, 2025a; CCC, 2025b).

6. Discussion

The example of France shows that public action on climate change has iteratively evolved in the country to produce a large number of strategic documents involving many different public and private actors, and multiple policy instruments that are more or less successful. Whereas it is easy to find gaps and inefficiencies in the overall evaluation of this framework, it is clear that public support for climate action has been the primary cause of the decreases in emissions in France which have been sustained over the past 20 years. Given this has been an iterative process, the risk of reversal of climate actions through successive decisions leading to reduced rates of decarbonisation is very real, in a context of reduced disposable income, political fragmentation, and the diffusion of misinformation and disinformation on social media. Hence the continued and broad support for climate policies that exist in France and worldwide today (Andre et al., 2024) is essential. Acknowledging in public and private discourses that climate action is necessary to protect households and businesses and essential to prosperity would help enhance climate policy support, and better align government actions with the expectations of populations.

Public action on adaptation is equally important to public action on mitigation discussed here. This is especially true as climate impacts from heat extremes, intense rainfall and floods, sea-level rise, and all their associated impacts will continue to rise for several decades until net zero CO2 emissions are reached globally. Climate-related impacts combine with natural variability so that extreme conditions continue to intensity (Ribes et al., 2022). France is particularly exposed to a range of climate impacts, with an extended coastal region (including in the overseas territory), dry Mediterranean climate exposed to intense rainfall and wildfires, an extended forest area, and mountainous regions which are a source of economic activity. At present, France tends to be functioning more on a reactive basis to extreme climate and weather events, with insufficient attention and resources put into planning and incorporating climate trends, including growing climate and weather extremes, into its planning at multiple levels (HCC, 2023a). The adoption of a reference trajectory for climate change reaching 4 °C in France is a positive step that will allow actors to scale their adaptation needs, as is the publication of the third revision of France’s adaptation plan. However, adaptation actions need to also be guided by regular reassessments of risks for France induced by climate change (e.g. CCC, 2022). With the latest such assessment for France dating to more than a decade (Jouzel, 2010), economic sectors need to be better informed about the growing risks faced by their industry. Much more is needed to expand adaptation policy and support across all sectors of the economy to make France more resilient to the growing impacts of climate change.

More broadly, tackling climate change requires that CO2 emissions reach net zero (with any remaining gross emissions compensated by removals) alongside substantial decreases in other greenhouse gases (GHG), in particular methane. As global emissions have not yet peaked but individual countries progress towards the implementation of climate actions, it is fundamental that insights and lessons learned be shared broadly to help entrain the broadest possible level of action. This can be done for example by dedicated support through networks such as the International Climate Council Network (ICCN). Climate responses need to take place and be resilient to the ups and downs of the world economy, emerging technologies (e.g. AI), and other social and security risks. Informed actions will help deliver good outcomes on multiple priorities.

Tackling GHG emissions across the economy has been daunting. Evidence provided here suggests that an important level of action is needed to achieve economy-wide decreases in emissions, with actions diffused across all sectors concerned and involving public and private actors, helped by support at the highest level as well as insights from the population. While these elements may not be all necessarily, and some actions may be redundant or suboptimal, the fact the so-called ecological transition (which is largely centred around tackling climate change) has been a stated central priority in France is evident and has certainly entrained key actors in the transition. Maintaining this level of priority for the next two decades is now the challenge.

Acknowledgements

The findings summarised in Sections 2.1, 3–5 draws on the work of the High Council on Climate (HCC; which I chaired until June 2024) but do not necessarily represent the exact views of the HCC. I refer you to its reports for the formal and latest evaluation of France’s public action on climate and for associated recommendations. I sincerely thank all the members of the HCC who have shared their experience and insights to establish the HCC, develop its evaluation framework, and assess policies and actions based on the best available data and information. I thank the secretariat of the HCC and in particular its directors for their dedication and professionalism. I thank C. Guivarch and S. Mondon for comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Finally, I thank my colleagues at the Global Carbon Budget for providing global and national-based CO2 emissions used in Sections 2.2–2.4, in particular R. Andrews, G. Peters, M.W. Jones and P. Friedlingstein. I am funded by the UK’s Royal Society through a Research Professorship (grant RSRP\R\241002).

Declaration of interests

The author is a member of the scientific advisory council of Société Générale. This institution had no role in the preparation of this review article.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0