1. Introduction

The global climate and biodiversity crises are intimately linked through their shared societal causes and their dynamics (IPCC, 2022; Pörtner, Scholes, et al., 2021). First, climate change already impacts ecosystems and their biodiversity and is expected to become a major driver of biodiversity change along with direct human use. Secondly, these impacts will limit the ability of the biosphere to contribute to climate mitigation and potentially feed forward to climate change through greenhouse gas emissions from disturbed ecosystems (e.g. fires, heat effects on peatland, melting permafrost) and alteration of terrestrial and oceanic surface properties. Furthermore, some climate mitigation and adaptation actions hold the potential to worsen harm to ecosystems and biodiversity. Hence, the interlinkages between the two crises are asymmetric, with climate change potentially worsening the degradation of biodiversity.

The drivers of biodiversity changes are well established globally (Díaz et al., 2019). Land and sea transformation for human use, habitat degradation and direct use of species are currently the dominant drivers, cumulating 80% of impacts on species (IPBES, 2022; WWF, 2014). Climate change ranks as the third current global driver of biodiversity change, but is set to have increasing impacts under all future greenhouse gas emission scenarios (Díaz et al., 2019; IPCC, 2022), although expected to be significantly less under more ambitious options like the 1.5 °C target (IPCC, 2018). These impacts result from climate trends including increasing temperatures, changed precipitation regimes, sea level rise and melting of polar and mountain ice, along with changes in natural disturbance regimes (e.g. storms, fire) and in the frequency and intensity of climate extremes (IPCC, 2012; IPCC, 2022). In this context, the expected increases in climate variability and extreme events in particular heat waves, drought and extreme precipitations (IPCC, 2021) are critical.

These direct effects of climate changes on biodiversity are observed on multiple facets of ecosystem structure and function (Lavorel, Lebreton, et al., 2017).

First, changes in climate parameters directly affect the physiology and behaviour of all organisms, through either increase (temperature) or decrease (water and thereby nutrient availability) in fundamental physical and chemical processes. Changes in phenology, the annual sequence of an organism’s developmental stages, are a prominent example with documented advances in growth and reproduction across multiple biota, and especially those with lower regulation capacity (e.g. insects, reptiles) or greater exposure (e.g. high arctic or alpine snowbed plants and vertebrates) (Vitasse et al., 2021). For example, across the European Alps insect emergence has advanced by an average of 6 days per decade since 1970, while singing and laying dates for birds have not changed significantly (ibid.). Physiological and behavioural change directly translate into changed survival and reproduction, and in some cases critical threats to population or even species persistence. For example, in Grisons, Switzerland, rock ptarmigan (Lagopus muta) has significantly shifted its entire range towards by +33 m per decade over the past 30 years, while snow hare (Lepus timidus) shifted its minimum elevation by +33 m per decade (Schai-Braun et al., 2021). These elevational shifts were mostly related to a reduced number of frost days. Because these direct responses are heterogeneous across biota and species, important biotic interactions can fail due to new mismatches (e.g. pollination, predator–prey) or synchronies (e.g. diseases) (Abarca and Spahn, 2021; Carroll et al., 2024).

Secondly, climate change has already modified species distributions polewards and towards higher altitudes. The current observed distributional shifts are ca. 0.02 °C annually, which is three to four times slower than current warming rates (Wiens and Zelinka, 2024). As with phenology, these adjustments are heterogeneous across biota and species (e.g. Carroll et al., 2024; Vitasse et al., 2021). Modelling of responses to climate change scenarios estimates that on average 20 to 30% of species will be threatened by extinction by 2100 (Díaz et al., 2019; IPCC, 2022). Specifically, most recent models based on observed shifts in species bioclimatic niches estimate extinction rates to average at 17% (Wiens and Zelinka, 2024). A recent modelling study based on observed species responses at their upper thermal range with three dispersal scenarios projected global extinction of 14%–32% species (potentially 3–6 million) across major terrestrial and marine biota by 2070 under the intermediate climate scenario RCP 4.5 (ibid.). Overall these projections are underpinned by large uncertainties relating especially to the lack of consideration of specific physiological responses, phenology or of biotic interactions that limit establishment into newly suitable habitat, and how species dispersal abilities are incorporated (Higgins et al., 2020; McMahon et al., 2011; Morin and Thuiller, 2009). Furthermore, they are based on average climate conditions and, with the exception of some physiological models, unable to consider the effects of climate variability and extremes and their consequences for natural disturbance regimes (Thonicke et al., 2020; M. G. Turner, Calder, et al., 2020).

Thirdly, changes in temperatures and precipitation directly impact ecosystem functioning through their effects on organisms’ physiological activities (e.g. water and nutrient uptake and recycling), biodisponibility of resources from water and soils or sediments, and biochemical process rates. Most reported impacts include the acceleration of carbon and water cycles from local to global scales, which won’t be detailed in this review. Importantly, ecosystem functioning is also affected indirectly by climate change through its impacts on the distribution of ecosystems from a global to regional scale (Sitch et al., 2008) and on community functional composition from local to global scales (Bugmann and Seidl, 2022; Chang et al., 2015; Sakschewski et al., 2015).

Lastly, in most extreme cases climate change has already started to transform ecosystem structure and functioning, sometimes referred to as regime shifts, ecosystem collapse or tipping points (Berdugo et al., 2020; Bergstrom et al., 2021; Leadley et al., 2014; Rocha, Peterson and Biggs, 2015) (see Section 2.1). Most reported examples include arctic deglaciation and glacier margins, tree colonisation of boreal tundra, rainforest to savanna transformation, tropical shrubland to desert transformation or coral reefs.

There are many uncertainties about mechanisms underpinning all these effects and their future projections which, among other limitations do not account for climate extremes and climate tipping points. In this context, this paper focuses on climate extremes and their combinations with other global change factors as critical, yet uncertain drivers of changes in ecosystem biodiversity and functioning. After briefly summarising the rich theoretical basis, I review evidence on the diverse dynamics of ecosystems in response to climate extremes and on their mechanisms. I then present the consequences of these responses for humans, and conversely how biodiversity and its responses to climate-related changes can be a resource for human adaptation to global environmental crises.

2. Conceptual and theoretical basis

2.1. Transformation of ecosystems and their biodiversity by climate change and climate extremes

Ecosystem transformation in response to climate change refers to a common body of understanding from complex systems theory (Folke et al., 2004), and prolific theoretical work. This literature and associated terminology address qualitative changes in ecosystems in response to climate change. In the following I present the main relevant terms and concepts, referring to transformation as their umbrella concept. Ecosystem transformation is defined as a change in the set of variables that control the system’s functioning, including their physical structure and their biodiversity. Ecosystem development at glacier forefronts is a well-known example of transformation, shifting from mineral surfaces with minimal biodiversity to multitrophic soil-vegetation-animal food webs (Ficetola et al., 2021). Transformation is often caused by changes in regulating physiological, demographic or biogeochemical feedback loops resulting in qualitatively different structure and function (Walker, Holling, et al., 2004). Transformation contrasts with resilience, where instead ecosystem structure, including biodiversity, and function return to their baseline state through multiple regulating and buffering mechanisms. Changes during transformation may operate at a variety of interacting scales, and be observable through a variety of relevant indicators. Multiple concepts and definitions of ecosystem transformation share key mechanisms including: nonlinear responses and hysteresis, the interplay of fast and slow variables and the role of synergistic effects, cascading impacts and feedbacks.

Referring to complex systems dynamics, transformation is often referred to as a regime shift where the large, persistent reorganisation of the structure and function results from the reconfiguration of abiotic and biotic control variables and processes (Rocha, Peterson and Biggs, 2015). Regime shifts can be driven by relatively linear processes like temperature-driven transitions from kelp forest to seaweed meadows (Wernberg et al., 2016), shrub expansion into boreal and alpine tundra ecosystems (Myers-Smith et al., 2011), and transitions from forest to savanna in response to changing fire regimes and grazing (Leadley et al., 2014; M. G. Turner, Calder, et al., 2020).

In contrast, a tipping point is qualitative change in ecosystem structure, its biodiversity and/or its function in response to a given value of a climatic variable considered as a threshold. To be considered as a tipping point, this change needs to be nonlinear and hard to reverse (hysteresis), because it is maintained by positive feedbacks. A particular case of ecological tipping point regards rate-tipping transformation, observed in response to a given rate of climate change or climate velocity, not just to a certain climate value (threshold state) (Synodinos et al., 2023). The extinction of species unable to adapt locally and/or to disperse and successfully establish at pace with changing climate is the best known case for rate-tipping points, representing priorities for conservation approaches such as translocation (Brito-Morales et al., 2018; Butt et al., 2021). Large-scale, biome-level ecosystem transformation has the potential for generating tipping points in regional and global climate (Leadley et al., 2014; Lenton et al., 2008).

Ecosystem collapse is an extreme case of ecosystem transformation and regime shift with limited capacity to recover, where “the ecosystem has lost key defining features and functions, and is characterised by declining spatial extent, increased environmental degradation, decreases in, or loss of, key species, disruption of biotic processes, and ultimately loss of ecosystem functions”, usually characterised by thresholds of transformation (Berdugo et al., 2020; Bergstrom et al., 2021). While the speed and linearity of collapse can vary across ecosystems, these transformations nearly always involve combinations of multiple climate and human factors, each of which act as press, i.e. continuous, or pulse, i.e. event-driven disturbances (Pörtner, Roberts, et al., 2022). For example, coral reef collapse is driven by combined trend temperature changes, heatwaves and the degradation of water quality through land use. Massive tree die-back events and the subsequent transformation of forest or woodland into degraded grassland combine long-term effects of increased temperature and drought, with extreme drought and fire events, pest outbreaks on already fragmented populations.

In practice, ecosystems can undergo multiple steps of transformation over the long-term. The case of drylands systems illustrates how transformation takes place as a series of quantitative and qualitative changes. As aridity increases, abrupt decays in aboveground productivity are first observed, followed by a loss of soil fertility due to the combined lack of biomass input, water availability and resulting disruption of biotic activity, and a final systemic collapse with the loss of plant cover (Berdugo et al., 2020).

The notion of ecosystem collapse is challenged by the conceptualisation of transformative change. When transformation leads to ecosystems with reassembled biotic communities with no current analogues and stable processes maintained by reconfigured feedback loops, these are considered as novel ecosystems (Ordonez et al., 2016). Post glaciation cases of such ecosystem development have been well documented (M. G. Turner, Calder, et al., 2020). Recent examples are emerging especially when climate change favours the colonisation and expansion of exotic species that alter biotic communities and induce self-reinforcing feedbacks on disturbance regimes and/or biogeochemical cycles (Prober et al., 2019).

2.2. Mechanisms underpinning ecosystem resilience and transformation with climate change and climate extremes

Complex systems dynamics of ecosystem transformation in response to climate trends and extremes are underpinned by a set of biotic mechanisms relevant to understanding the role of different facets of biodiversity. These have been supported by the combination of evidence from theoretical modelling, field observation including long-term physical, ecological and some cultural data series and experiments (Henne et al., 2018; Thonicke et al., 2020).

Stable ecosystems maintain their structural attributes and multiple ecosystem functions such as productivity, carbon sequestration or pollination in the face of inter-annual climate variability and disruption by disturbances including climate extremes. Ecosystem stability can be assessed by referring to its different components including resistance to change especially in response to extreme events, and processes of recovery towards a baseline (resilience) or an alternative state (transformation) (Falk et al., 2019; Ingrisch and Bahn, 2018; Oliver et al., 2015). Stability is maintained by a multiplicity of interplaying mechanisms from individuals (physiological and behavioural) to populations (demographic and evolutionary), communities (biotic interactions and dispersal), ecosystems (e.g. biogeochemical) and landscapes (lateral flows of organisms, matter and energy) that can buffer the effects of environmental variation (Felton and Smith, 2017; Oliver et al., 2015; Schlägel et al., 2020).

Consistent with resilience theory (Walker, Holling, et al., 2004), multiple lines of evidence from experiments (Isbell, Craven, et al., 2015) and long-term observations at community (Liang et al., 2022) to continental level (Oliveira et al., 2022) suggest that greater biodiversity stabilizes natural communities and ecosystems. The long-running debate on the relationship between species diversity and stability (McCann, 2000) is beyond the scope of this paper, yet established mechanisms can be summarised as follows. First greater biotic diversity, including genetic, phenotypic, species and functional diversity, allows redundancy, the presence of alternative biota for a same ecological function, and insurance, the complementarity across biota with respect to preferred environmental conditions (e.g. climate, resources, disturbances). Secondly, the complexity of biotic interaction networks is expected to support these two mechanisms, where intermediate interaction density and modularity allow a trade-off between complementary local responses and propagation between network elements (Montoya et al., 2006). Thirdly, intermediate physical connectivity is likewise expected to stabilize spatial networks of communities and ecosystems through the benefits of dispersal across landscape elements with different exposure to climate and other disruptions (Gravel et al., 2016). These mechanisms are combined across spatial and temporal scales, governing trajectories of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning (Falk et al., 2019; Schlägel et al., 2020).

Many of these mechanisms can be related to functional traits of biota (de Bello et al., 2021; Oliver et al., 2015; Walker, Kinzig, et al., 1999). Specifically, functional traits underpin three interacting mechanisms of stability. First, the traits of dominant (i.e. most abundant) species or genotypes determine many ecosystem processes by their prevalent effects through their biomass contribution, and hence resistance and recovery after perturbations. Secondly, complementary trait values across species or genotypes, broadly referred to as functional diversity, allow differing responses to environmental variability and hence compensatory dynamics at the ecosystem to landscape scale. Thirdly and conversely, similarity across species and genotypes in structural, physiological, biochemical or phenological characteristics affecting target ecosystem functions such as biomass production and nutrient recycling, i.e. effect traits, coupled with dissimilarity in their characteristics driving the effects of climate and disturbances on their survival, growth and reproduction, i.e. response traits, underpin redundancy (Lavorel and Garnier, 2002). Ultimately, these three mechanisms operate concomitantly in specific ecosystems through modifications by climate variability, climate trends and extremes of the abundance distribution of trait values in biotic communities (Kohler et al., 2017) (Box 1). The resulting trait value distributions then either buffer or propagate environmental change effects on ecosystem functions.

In addition to stability and resilience, which maintain ecosystem structure and function over the long term, mechanisms of transformation are essential when facing extreme climate change and/or novel climatic and disturbance regimes. Transformability, the ability to transform, is underpinned by specific mechanisms (Lavorel, M. Colloff, et al., 2015). Response diversity can mediate ecological transformation in several ways: (1) through shifting contributions of different species groups, especially across groups with differing ecological niches like seeder vs. resprouter trees under changing fire regimes; (2) through response diversity within keystone functional groups such as structuring tussock grasses in grasslands and savannas, or coral vs. algae in tropical reefs; and (3) through response diversity in hyperdiverse communities like tropical rainforest. Landscape and seascape connectivity plays a key role not only in resilience but also in the transformation of fragmented systems through its effects on propagule flows that are necessary for disturbance responses and for the migration of climatically suitable species. Transformation depends on immigration by, or dominance of, species with novel traits where previously dominant traits have been lost. Novel ecosystems containing exotic species, following extinction of dominant native species, are likely to become commonplace under future climate (Prober et al., 2019).

Box 1—Functional dynamics in the transformation of ecosystems (summarised from Kohler et al., 2017).

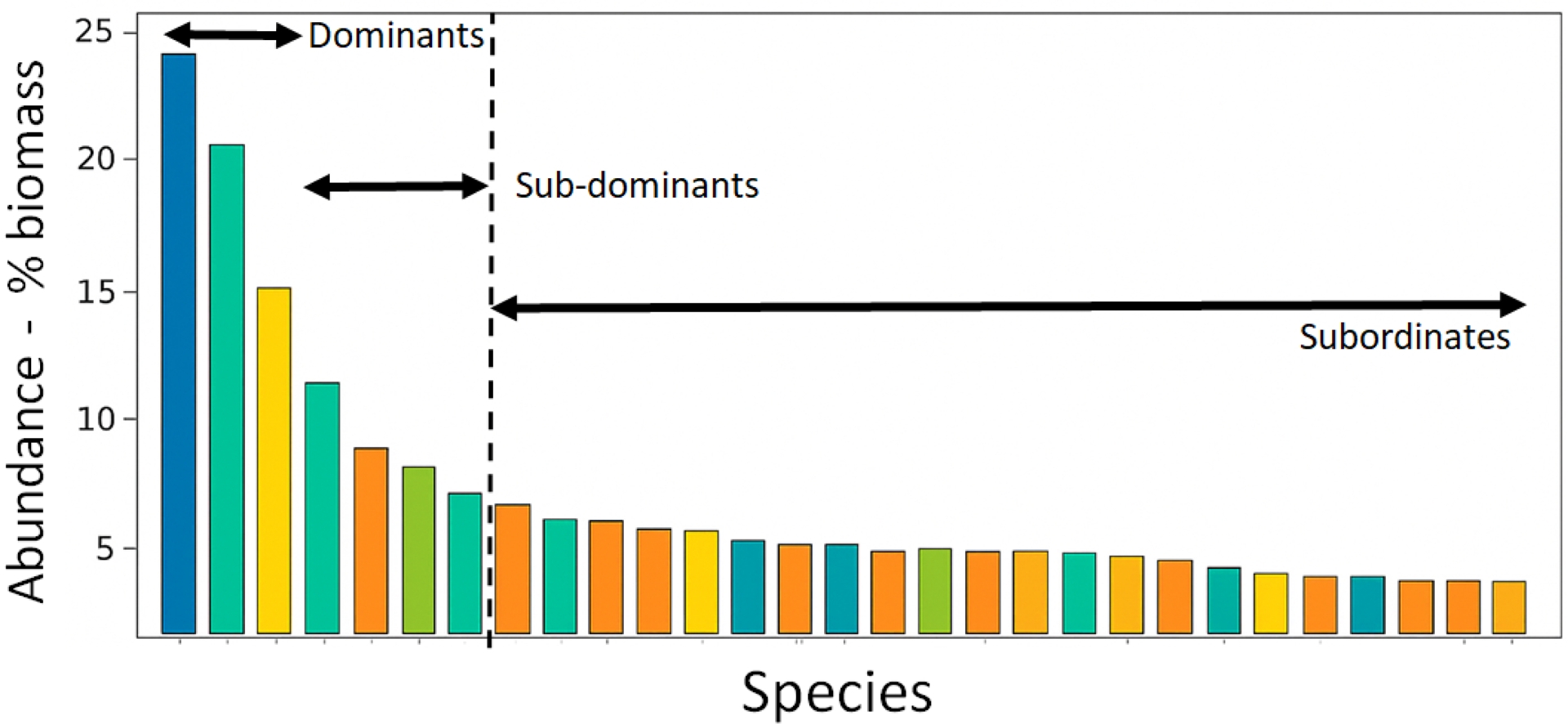

The dynamics of change in ecosystem biodiversity and functioning can be assessed from the analysis of the functional structure of communities (Figure 1).

Abundance structure of a community. Dominant species have a significantly greater abundance across all sampled communities; sub-dominants have intermediate abundance which can increase or decrease across communities; subordinates have a low abundance across all communities (Grime, 1998). Each bar represents a species, with colours representing different functional groups based on traits for a function of interest.

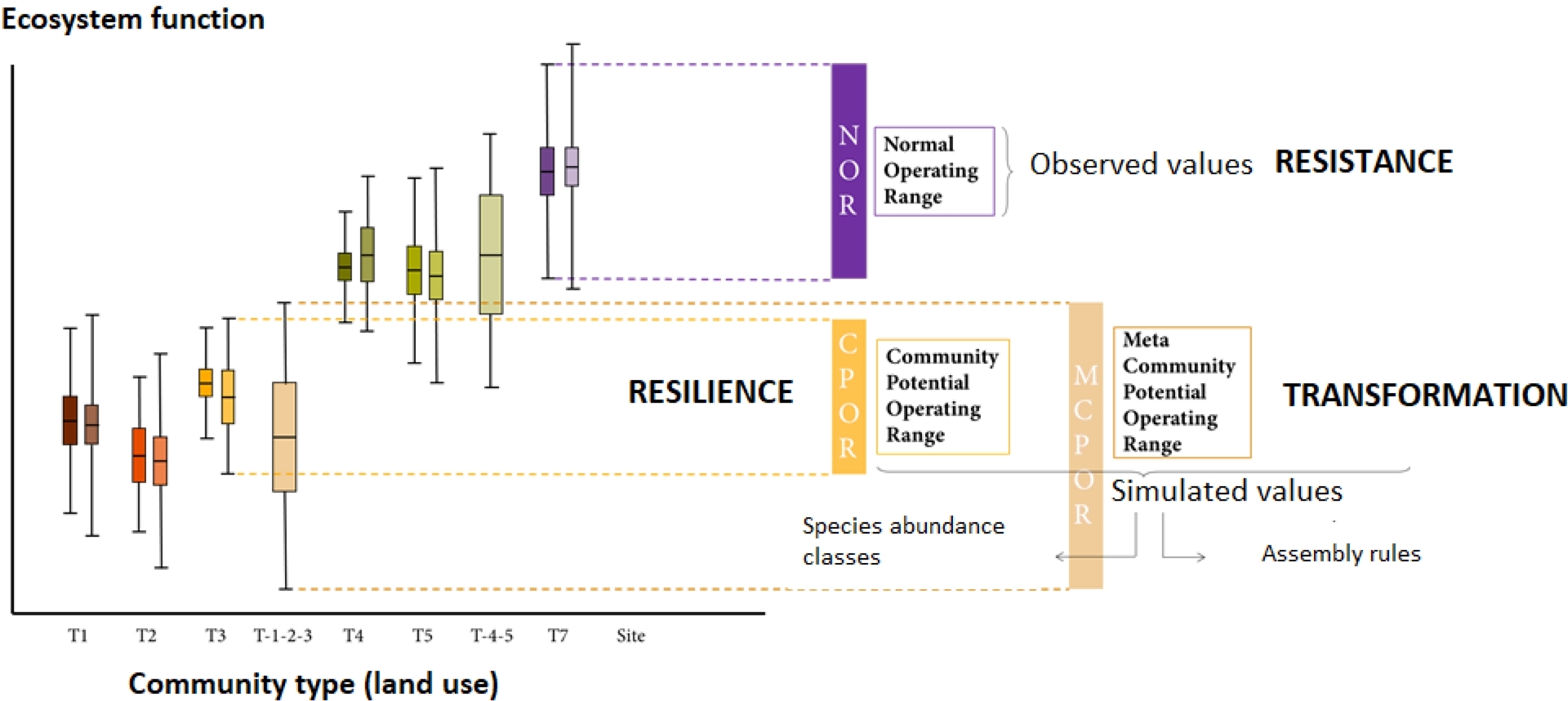

Ecosystem function is estimated from its quantitative relationship to species traits and their abundances (Lavorel, Grigulis, et al., 2011). Natural variation in space (multiple locations within the landscape or region) or time (multiple years) of the ecosystem function is considered as the stable range of variation, or normal operating range, within which the ecosystem is considered to resist environmental change. Historical climate variability is compatible with the persistence of species within each community, but drives changes in their relative abundances within their respective dominance groups. The corresponding range of variation of the ecosystem function, or community potential operating range, is simulated for iterations of such community reassembly, and considered as its resilience. Extreme climate events exceed the tolerance of some of the species from the community, and open opportunities for colonisation by species from other communities with a similar history (meta-community), leading to a new community. The corresponding range of variation of the ecosystem function, the meta-community operating range, is calculated for iterations of such community reassembly, and considered as its transformation (Figure 2).

Variability of an ecosystem function according to observed variability (Normal operating range—NOR), response of a stable community to natural climate variability (Community operating range—CPOR) and transformation by a climate extreme (Meta-community operating range).

3. Evidence for nonlinear effects of climate extremes on ecosystems

Section 2 showed how mechanisms of ecosystem transformation are explained by complex systems theory and by the effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning. Yet, we lack comprehensive evidence on the range of transformations from direct effects of climate extremes to more complex and impactful interactions. In line with recent syntheses (M. G. Turner, Calder, et al., 2020), I hypothesise that ecosystem transformation tends to unfold in these more complex situations. In the following I summarise evidence for such nonlinear effects of climate extremes on ecosystems.

3.1. Observed effects of compound effects of climate extremes

Climate change is associated with the increasing frequency and intensity of climate extremes, as well as with not only single but sequences of extreme events (IPCC, 2012; IPCC, 2022; Thonicke et al., 2020). While observational, experimental and modelling evidence and understanding of the effects of single extremes on ecosystems are increasing and yet incomplete (De Boeck, Bloor, et al., 2018; Frank et al., 2015; M. G. Turner, Calder, et al., 2020), combined effects of extremes with climate trends and compound extremes are still a great source of uncertainty on future trajectories of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.

Rare experiments combining extreme events with modifications of baseline climate show abrupt decreases in ecosystem functioning. For example the combination of heatwaves with drought in temperate grasslands has variable effects on plant growth and senescence depending on plant traits, but result in both short- and medium-term reductions in primary production (Benot et al., 2014; De Boeck, Bassin, et al., 2016; Zwicke et al., 2013), along with decreased carbon sequestration and increased greenhouse gas emissions (Fuchslueger et al., 2016; Ingrisch, Karlowsky, et al., 2018; Karlowsky et al., 2018; Knapp et al., 2024). Such effects result from physiological stress on photosynthesis, reduced regulation by plant transpiration, and modified plant–soil interactions through plant exudates and soil microbial community composition and metabolism.

Even fewer experiments have addressed successive climate extremes, showing shifts in responses from physiological resilience to transformation of community composition to morphological, phenological and physiological avoidance and resistance strategies (Dreesen et al., 2014; Knapp et al., 2024). Here, observation of recent events informs about the cumulated impacts of successive climate extremes and their abrupt effects on ecosystems. For example, in central Europe the two extreme summers of 2018 and 2019 with an exceptional drought and heat waves showed variable, nonlinear effects depending on specific exposure and ecosystems (Bastos et al., 2020). Agricultural areas, and especially grasslands, showed by 2019 exceptional reductions in plant cover and activity resulting from lasting soil water reduction and cumulated physiological effects. In contrast, forests showed dramatic senescence only by 2019, due to delayed physiological effects. Yet, the synthesis of observations across networks of long-term forest monitoring plots shows that the structure of European temperate forests has been resilient to past large and severe disturbances (windthrow, fire, bark beetle outbreaks) and concurrent climate conditions (Cerioni et al., 2024). Still, long-term shifts in composition to early-successional species may be promoted by shorter successions of events.

3.2. Evidence for benefits of biodiversity for ecosystem resilience to climate extremes

Experimental approaches provide mixed support for the benefits of biodiversity for the resilience of ecosystem functioning to climate extremes expected from theory. Across 46 grassland species richness manipulation experiments experiencing inter-annual climate variability, benefits of species richness to aboveground net primary production were largest during extreme wet or extreme dry years, supporting the insurance mechanism of greater likelihood of drought or wet adapted species in more diverse mixtures (Isbell, Craven, et al., 2015). Yet, in a 14-year combined grassland biodiversity and climate manipulation experiment, species richness benefited resistance of aboveground net primary production to extreme wet or dry treatments no more than to moderate wet or dry treatments (Hossain et al., 2022). However, species richness decreased resilience to moderate or extreme dry treatments, and had no effect on resilience to moderate or extreme wet conditions. A meta-analysis comprising 28 experiments on high vs. low biodiversity plant communities exposed to extreme drought (19 experiments of which 17 in grasslands and 2 in forests) or extreme precipitation (9 experiments in grasslands) concluded that while higher biodiversity promoted higher aboveground biomass production and these extremes significantly reduced that production, higher biodiversity did significantly not increase either resistance or recovery in the face of these simulated extremes (De Boeck, Bloor, et al., 2018). These conclusions likely reflect the low relevance of species richness per se to community responses to extremes, where instead responses are likely driven by functional traits (de Bello et al., 2021). The relevant variation in functional traits within communities is largely driven by interspecific variation and community assembly mechanisms in response to environmental drivers and biogeographic, site and evolutionary history (Cavender-Bares et al., 2016; Kraft et al., 2015). Moreover, intraspecific trait variation, reflecting genetic diversity and phenotypic responses, can also be a significant contributor (Sanderson et al., 2023). Such plant but also microbial trait driven responses of ecosystem functioning are evidenced in naturally species-rich grasslands where dominant species traits determine both resistance and resilience to experimental climate extremes (Karlowsky et al., 2018; Piton et al., 2020; Schuchardt et al., 2023). Also consistent with trait-based mechanisms, biodiversity benefits to ecosystem functioning in experimental communities are greatest when considering multiple combined environmental changes, reflecting functional complementarity through functional divergence (Isbell, Calcagno, et al., 2011).

3.3. Indirect effects of climate extremes on ecosystem responses to other global change factors

Beyond their direct effects, climate extremes exacerbate the effects of other global change factors responsible for contemporary modifications of biodiversity: the human use of ecosystems and species, invasive alien species and pollution (Díaz et al., 2019).

First, climate extremes can further undermine the persistence of populations that are already threatened by land or sea use or direct exploitation (Foden et al., 2019). Conversely, landscape and seascape fragmentation by human use reduces species movement abilities after extreme storms or fires, thereby increasing local to regional extinction risks and ecosystem transformation (Bergstrom et al., 2021; M. G. Turner, Calder, et al., 2020).

Secondly, climate change, but also climate extremes that destroy local populations of native species favour the spread of invasive alien species (Diez et al., 2012). Yet, while mean climate change increases favourable habitats, extreme heat, drought or precipitation may reduce the spread of invasive species as shown for example in the case of six vertebrates for the Iberian Peninsula (Baquero et al., 2021) or aquatic invertebrates (McDowell et al., 2017). By transforming ecosystem structure and key attributes like biomass or water regimes, invasive species can amplify the effects of climate extremes. This is particularly significant through changes in disturbance regimes. For example, in Australia the continental scale expansion of introduced buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris) into semi-arid and arid rangelands strongly increases fuel quantity and continuity, fostering larger and more intense fires (Schlesinger et al., 2013). In the same way, invasive species colonising riparian corridors and floodplains alter hydrological regimes during floods through changing biomass and sediment accumulation (Kiss et al., 2019).

Thirdly, climate extremes combine with other disturbances, like herbivory and pests to transform ecosystem structure and biodiversity. Modelling suggests that in European forests, extensive browsing by extant ungulate populations is likely to critically limit spontaneous adaptation of forest composition to climate scenarios through setting back the recruitment of warm-adapted species like oaks (Quercus robur and Q. petraea) (Dobor et al., 2024). While knowledge is still incomplete on how and when extreme drought favours tree mortality through subsequent bark beetle outbreaks (Jaime et al., 2024), those forests submitted to their combination can catalyse vulnerability to subsequent disturbances like windthrow and fire (Senf and Seidl, 2021; M. G. Turner, Calder, et al., 2020).

3.4. When resilience is breached: systemic effects, cascades and interactions

Together these cases support the emergence of novel disturbance regimes under climate change and climate extremes that may challenge ecological resilience and promote novel ecosystems (M. G. Turner and Seidl, 2023). These transformations can in turn propagate to further regime shifts through cascading effects. The analysis of 30 characteristic regime shifts at a global scale revealed that these are most frequently driven by shared drivers, of which climate (especially for aquatic and marine systems) and agriculture or land cover conversions were prevalent (Rocha, Peterson, Bodin, et al., 2018). Effects of shared drivers are then compounded by domino effects across adjacent or connected ecosystems at ecotones (e.g. coastal systems including mangroves or tidal systems), or emerging feedbacks in space and/or time through changed climate regimes, fire, agriculture or urbanisation. In particular, the conversion of grassland to desert or arid systems can impact precipitation regimes and accelerate aridification. Likewise, poleward or altitudinal migration of tree lines in boreal and mountain regions can enhance the increase in temperature due to large increases in albedo.

4. Implications for humans and nature-based adaptation

By altering ecosystem structure, biodiversity and functioning, climate change impacts the whole range of nature’s contributions to people (Runting et al., 2017). Specifically increasing climate extremes have large impacts on all material benefits of food, raw materials (including wood) and freshwater, on local to global climate regulation and on mitigation of natural risks (Thonicke et al., 2020). Furthermore, climate change decreases these very functions that are critical to climate adaptation and mitigation. This includes the weakening of terrestrial carbon sinks (Lauerwald et al., 2024; Seidl et al., 2014) and the degradation of ecosystems with risk protection benefits like forests regulating erosion and floods at the head of catchments or in flood-prone valleys (Pramova et al., 2012), protection forests (Stritih et al., 2024) or wetlands (Xi et al., 2021).

Ecosystems in good condition are however critical to social adaptation to climate change (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016; M. J. Colloff et al., 2020; Lavorel, M. Colloff, et al., 2015). Such nature’s contributions to adaptation comprise not only climate change and risk mitigation, but also the resilience and transformative ability of genetically, taxonomically or functionally diverse and spatially connected ecosystems (see Section 2.1), along with the social construction of new values for transformed ecosystems. As an example, emergent ecosystems at glacier forefronts reduce risks from landslides and floods, sequester carbon in vegetation and soil, provide new grazing grounds and forest products and offer new cultural contributions to art, education or research, as well as spiritual connections (Khedim et al., 2021; Zimmer et al., 2022). Multifunctionality is typical of nature-based solutions, which often deliver multiple co-benefits beyond their primary objectives of climate mitigation or risk mitigation (Chausson et al., 2020; González-García et al., 2025; Lavorel, Locatelli, et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the concept of nature’s contributions to adaptation recognises that human connections to nature, capitals, and social processes are necessary for people to implement and benefit from these contributions (Lavorel, Locatelli, et al., 2020; Locatelli et al., 2025). For example, in the Grenoble region (France) nature-based solutions of ecosystem conservation, restoration and management are central to policy and planning documents. They comprise among others: increasing urban vegetation, restoration of wetlands and floodplains, restoring landscape connectivity to support species migration, agroforestry or adaptive management of forests. Their implementation and scaling requires a combination of levers, including knowledge production and sharing, changing and supporting nature’s values and perception, local governance, supportive policies, financial support, and the reinforcement of the landscape planning culture (Bruley et al., 2025).

5. Conclusion

Climate extremes, often when combined with climate trends and other disturbances and global change factors can transform the structure, biodiversity and functioning of ecosystems. Some of these changes are qualitative, and for some abrupt, contributing to the global and local loss of biodiversity, and to critical changes in ecosystem functions and feedbacks to the global climate. Such transformations can imperil human livelihoods and societies. Yet, biodiversity provides an insurance for ecosystems and humans in the face of these transformations. Processes of social adaptation enable the mobilisation of biodiversity for adaptation, requiring in turn a transformation in the production and sharing of knowledge of relevant ecological processes, in values for nature and in social relations.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a contribution from the Transformative Adaptation Research Alliance (TARA, https://research.csiro.au/tara/), an international network of researchers and practitioners dedicated to the development and implementation of novel approaches to transformative adaptation to global change. This paper contributes to the Programme on Ecosystem Change and Society (PECS, a Future Earth core project) and its working group on “Nature-based transformations: Evolving human–nature interactions under changing climate” (https://pecs-science.org/nature-based-transformations/).

Declaration of interests

The author does not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and has declared no affiliations other than their research organization.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0