1 Introduction

One of the major challenges for environmental conservation in the next century will be the preservation of the species-rich habitats of the Amazon Basin in South America 〚1〛. In addition, over the past two decades, declining lissamphibian populations have been observed in many parts of the world: America, Australia, Britain and Europe 〚2–4〛. However, it has also been observed that lissamphibians have the highest rate of description of new species of any group 〚5〛. A recent study established an inventory of the species present in French Guiana, in which more than 15 families and 110 species are listed, illustrating a great biodiversity 〚6–8〛. This work constituted the first study of the classification of lissamphibian fauna in northeastern South America, using several criteria: morphology, ecology, behaviour, and biogeography. Moreover, due to the high homoplasic level for these criteria (ecological adaptation, morphological convergence), the phylogenetic relationships of these different species remained unclear. The use of molecular tools will be a precious help in clarifying the systematic of these problematic groups.

Hylidae are one of the most diverse and widely distributed frog family in the world. Indeed, the members of this family are found in South and North America, Europe, Asia (excluding India), Australia and New Guinea 〚9〛. The family contains 680 species, classified into 40 genera, with the highest number present in tropical America: including five genera and at least 38 species in French Guiana 〚6〛. This family is arranged into four subfamilies: Pelodryadinae, Phyllomedusinae, Hemiphractinae and Hylinae 〚10〛.

Phylogenetic relationships within this diverse group remain unclear, despite numerous studies of their evolutionary history using morphological, behavioural, ecological, and biochemical approaches 〚11,12〛. The Hylinae subfamily is a diverse group of frogs, placed together because they do not possess the distinctive features of the other three subfamilies 〚13〛.

Mitochondrial DNA (mt DNA) has been the molecular marker of choice in numerous phylogenetic analyses of vertebrate relationships and hence, it was expected to be appropriate for helping to resolve some aspects of the lissamphibian phylogeny 〚14–16〛 or answering the question of the origin of the Lissamphibian 〚17〛. The mitochondrial 16S ribosomal DNA gene has been extensively sequenced and analysed, often being used in systematic studies of families and genera in lissamphibian 〚18–20〛. Partial sequences have been widely used in the assessment of relationships within and between amphibian genera. Thus mitochondrial gene evolution has proven effective in investigating evolutionary relationships among closely related species 〚21〛.

Our preliminary attempt was to explore the relationships of some French Guiana frogs and to investigate the relationships of French Guiana Hylidae by using partial sequences of mitochondrial ribosomal 16S gene. We analysed eight specimens belonging to the Hylidae family: five specimens belonging to the Scinax genus, two of the Hyla genus, and one of the Osteocephalus genus. One specimen of the Centrolenidae (Hyalinobatrachium genus) was used to verify the hypothetical paraphyletic origin of the Hylidae family 〚16〛, and two Rana specimens were used as an outgroup (Ranidae). Furthermore, we used 26 sequences selected from GenBank representing the other subfamily of the Hylidae (Table 1).

List of batrachians used for this study with the locality number (see Fig. 1)

| Family | Subfamily | Species | Genbank accession number | Origin (locality number) |

| Ranidae | Raninae | Rana palmipes 1 | AF467265 | Guiana Trois Sauts (5) |

| Rana palmipes 2 | AF467266 | Guiana Trois Sauts (5) | ||

| Hylidae | Hemiphractinae | Gastrotheca riobambae | U39976 | |

| Hylinae | Scinax ruber | AF467264 | Guiana Antecum Pata (6) | |

| Scinax cruentommus | AF467263 | Guiana Mountain of Kaw (3) | ||

| Scinax jolyi 1 | AF467261 | Guiana Swamp of Kaw (3) | ||

| Scinax jolyi 2 | AF467261 | Guiana Creek of Gabrielle (2) | ||

| Scinax nebulosus | AF467262 | Guiana Regina Road | ||

| St Georges (4) | ||||

| Hyla minuta | AF308113 | |||

| Hyla marmorata | AF308115 | |||

| Hyla triangulum | AF308108 | |||

| Hyla leucophyllata | AF308093 | |||

| Hyla sarayacuensis | AF308104 | |||

| Hyla bifurca | AF308099 | |||

| Hyla ebraccata | AF308101 | |||

| Hyla elegans | AF308103 | |||

| Hyla carnifex | AF308117 | |||

| Hyla labialis | AF308119 | |||

| Hyla parviceps | AF308111 | |||

| Hyla microcephala | AF308110 | |||

| Hyla raniceps | AF467269 | Guyane Yi-Yi’s Creek (1) | ||

| Hyla dentei | AF467270 | Guiana Mountain of Kaw (3) | ||

| Osteocephalus oophagus | AF467267 | Guiana Mountain of Kaw (3) | ||

| Smilisca phaeota | U39979 | |||

| Pelodryadinae | Litoria genimaculata 1 | AF136300 | ||

| Litoria genimaculata 2 | AF136298 | |||

| Litoria eucnemis | AF136301 | |||

| Litoria nannotis | AF136325 | |||

| Litoria rheocola | AF136326 | |||

| Litoria thesaurensis | AF136318 | |||

| Litoria lesueuri | AF136317 | |||

| Litoria subglandulosa | AF282613 | |||

| Litoria caerulea | AF136316 | |||

| Litoria exophthalmia | AF136314 | |||

| Nyctimystes dayi | AF136329 | |||

| Phyllomedusinae | Phyllomedusa palliata | U39985 | ||

| Centrolenidae | Hyalinobatrachium taylori | AF467268 | Guiana Creek of Gabrielle (2) |

The tree frogs of the Scinax genus are characterised by a concave loreal region; their finger’s discs are dilated, wider than long and with webbing absent or reduced between the first and second toes. The Scinax genus (ancient Ololygon genus) shows two filaments by spermatozoon (in contrast to only one for frogs of Hyla genus) but this discriminating character cannot be used in field key, due to the difficulty in visualising this characteristic in the field or in a collection specimen 〚6,22,23〛.

In this study, we addressed the following questions: what are the phylogenetic affinities of the enigmatic Scinax genus within the Hylinae, and what are the relationships among the hylid subfamilies?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Biological samples

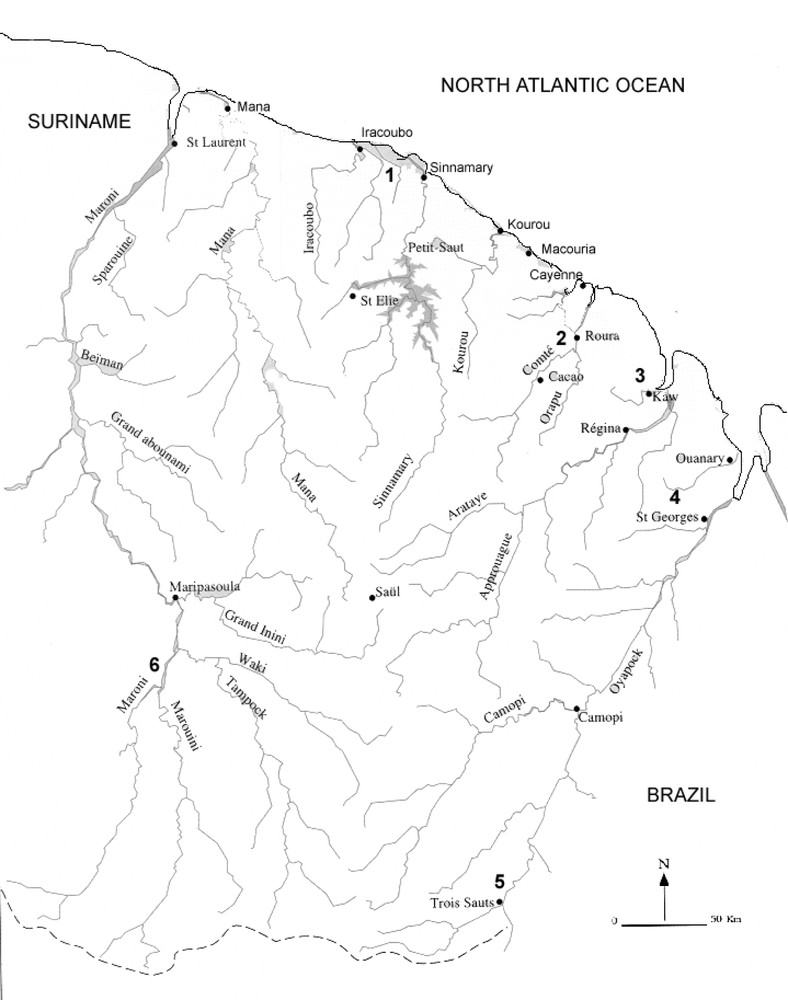

Eleven DNA sequences were obtained from specimens collected by our team in French Guiana over a four-year period. Data for the specimens examined are given in Table 1 and a map of collecting localities is given in Fig. 1. Eleven new sequences from nine species, representing the Hylidae (Scinax, Osteocephalus, Hyla), Ranidae (Rana), and Centrolenidae (Hyalinobatrachium) were added to those collected from GenBank. Tissue samples were derived from either skeletal muscle by performing a biopsy. For collection specimens, we used liver tissues preserved in ethanol.

Map of French Guiana showing the localities of the samples collected. © Service du Patrimoine Naturel, MNHN, Paris, 2000.

2.2 Molecular data

Total DNA was extracted according to the method of Taberlet and Bouvet 〚24〛 and 540-bp segment of 16S rDNA gene was amplified by standard PCR techniques using the following primers: one conserved primer N-934 〚25〛 5’CGCCTGTTTACCAAAAACATCG 3’ (forward) and one universal primer 3259 〚26〛 5’ CCGCTTTGAGCTCAGATCA 3’ (reverse). Thermal cycle amplifications were performed in a 50 μl tube adapted to the method of Gilles et al. 〚27〛. Cycle parameters for 16S rDNA region were as follows: 2 min at 92 °C (one cycle); 15 s at 92 °C, 45 s at 46 °C, 90 s at 72 °C (five cycles); 15 s at 92 °C, 45 s at 48 °C, 1 min at 72 °C (30 cycles); 7 min at 72 °C (one cycle). A second, higher annealing temperature of 48 °C was used for more stringent annealing conditions when necessary. The PCR products were stored at –20 °C. Fragments were directly sequenced from the purified PCR products using an automated sequencer (Genome Express S.A.) and the PCR primers. Sequences were obtained from GenBank for the following taxa (see Table 1 for accession codes): Litoria, Gastrotheca, Smilisca, Phyllomedusa genera and some Hyla species.

2.3 Data analysis

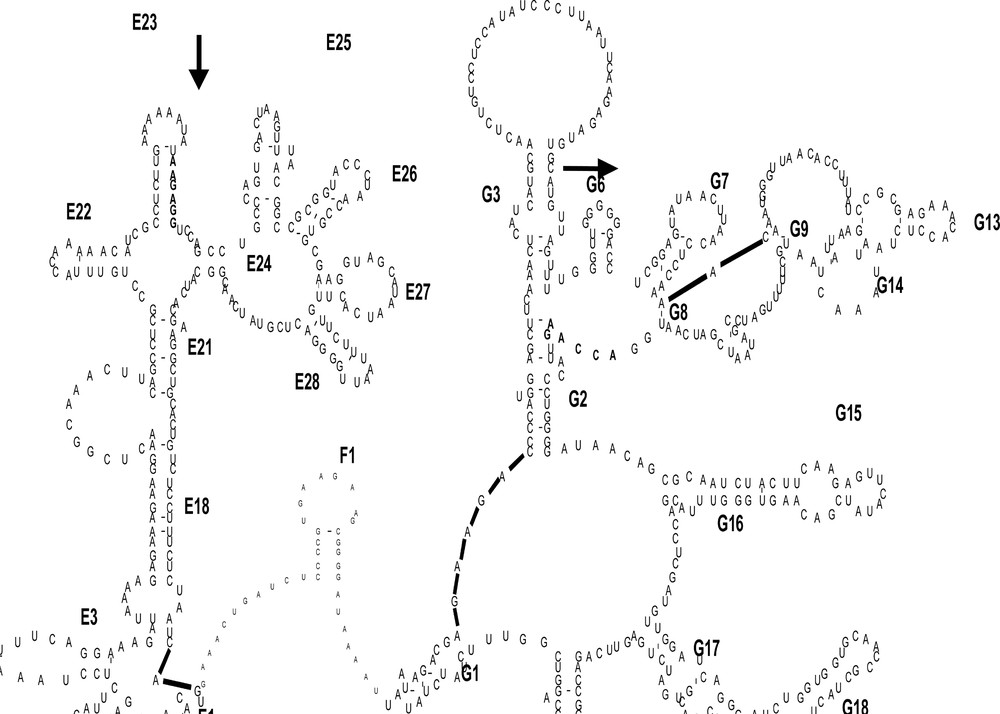

All 16S rDNA sequences were aligned using Clustal X 〚28〛 and compared with the secondary structure alignment 〚29〛 (Fig. 2). Visualisation of the secondary structure was done using the same process described in 〚30〛, which allowed for identification of the five distinct regions: three conserved segments (C1 = positions 1 to 204; C2 = 284 to 325; and C3 = 346 to 427), separated by two variable stretches (V1 = positions 205 to 283 and V2 = positions 326 to 345).

Part of the secondary structure of the 16S rRNA gene of Rana pipiens. First sites and the last sites of the amplified segment are in bold beside the two arrows.

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using two different approaches: (1) the Neighbour-Joining (NJ) method 〚31〛, based on a matrix of the Kimura two-parameter distance 〚32〛, and the Kimura two-parameter distance with an estimation of alpha parameter equal to 1.63 in Mega 〚33〛; (2) a cladistic approach, using the maximum parsimony (MP) criterion (heuristic search of PAUP* 〚34〛). Robustness of nodes was estimated by running a bootstrap test with 1000 replicates for NJ trees, and 1000 replicates for MP trees (heuristic search of PAUP* 〚34〛 with 10 random additions of taxa and TBR branch-swapping.

Differences in topology between trees based on conserved versus variable regions of the 16S rDNA sequences were assessed by the partition homogeneity test (PHT) 〚35〛 as implemented in PAUP* 〚34〛 with a significant level of 0.05. This test was useful to detect incongruence between different partitions 〚30,36,37〛. To test the robustness of branches in the tree Bremer’s decay index 〚38〛 and Templeton’s test (Wilcoxon sign-rank tests 〚39〛 were computed. Relative rate tests were conducted using Phyltest 〚40〛.

3 Results

3.1 Evolutionary pattern of the partial 16S rDNA

We used the partial alignment (332 positions) of the 16S rDNA. This partial alignment corresponded to the overlap of the different sequences (we removed the positions 1–95 of the conserved partition C1 = positions 1 to 204).

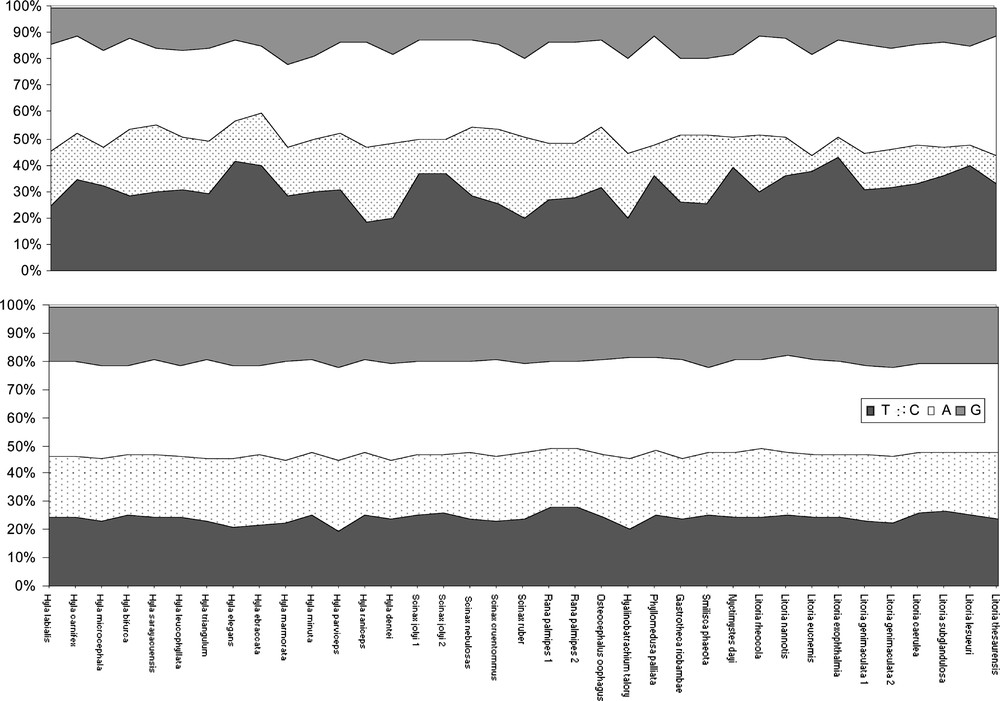

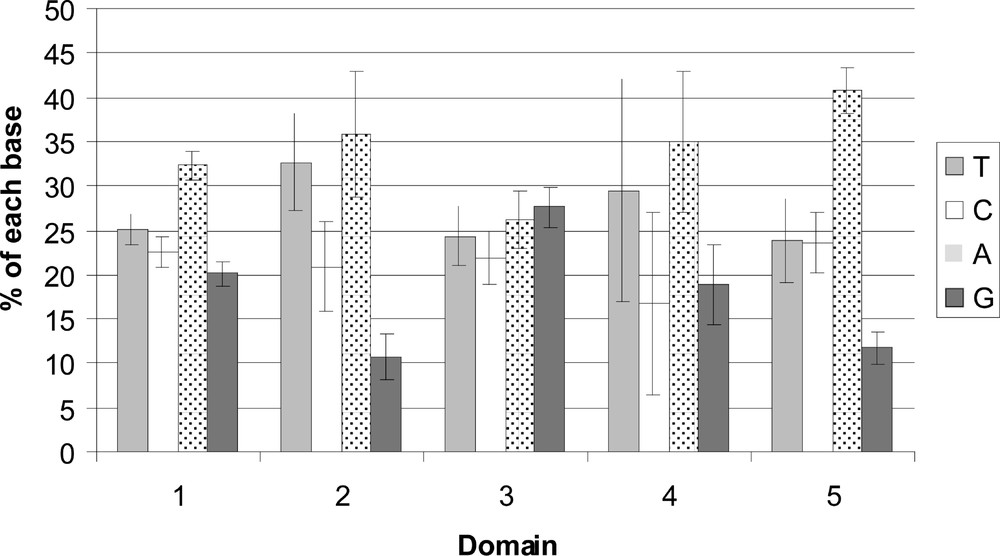

For the conserved zones, no significant differences in nucleotide compositions between the species were detected using the χ2 test (α = 0.05). The mean base frequencies (in percent) were A: 33.1, C: 22.66, G: 19.8 and T: 24.43 (Fig. 3a). For the variable zones, significant differences in nucleotide compositions between the species were detected using the χ2 test (alpha = 0.05) for six specimens (Hyla raniceps, Hyla dentei, Scinax ruber, Litoria eucnemis, Litoria exophthalmia, and Litoria lesueuri). In these regions, the mean base frequencies (in percent) was A: 35.4, C: 18.8, G: 14.7 and T: 31.1 (Fig. 3b).

Percentage of nucleotide compositions for each species representing the variable zones, V1 = positions 205 to 283 and V2 = positions 326 to 345 (3a) and the conserved zones C1 = positions 1 to 204; C2 = 284 to 325; and C3 = 346 to 427 (3b). The positions 1–95 of C1 were not used in this analysis due to the short length of some GenBank species.

The differences in base composition for each domain can be visualised in Fig. 4. Considering the heterogeneity in DNA length for each domain, these differences are not significantly different using a χ2 test (p value = 0.63).

Differences in base composition for each domains in using the partial segment of the 16S rDNA (332 pb) for the five distinct regions: three conserved segments (C1 = positions 1–204; C2 = 284–325; C3 = 346–427), separated by two variable stretches (V1 = positions 205–283 and V2 = positions 326–345). The position 1–95 of C1 was not used in this analysis due to the short length of some GenBank species.

3.1.1 Genetic variability

We estimated the genetic variability for the three genera represented in this study using a Kimura two-parameter distance. For the Scinax genus, we found a value equal to 0.249 ± 0.025 (0.171 ± 0.016 if we consider the complete alignment, i.e. 427 bases). The Litoria genus yielded a value of 0.161 ± 0.016 and the Hyla genus gave a distance of 0.224 ± 0.019. The variability within the Hylidae family ranged from 0.268 ± 0.04 (excluding the Scinax genus) to 0.290 ± 0.04 (including the Scinax genus).

Surprisingly, the distance between the Centrolenidae and the Hylidae was only 0.295 (± 0.036). Indeed, the level of differentiation observed between the Scinax genus and the other members of the Hylidae was high 0.332 ± 0.0376 (see Appendix).

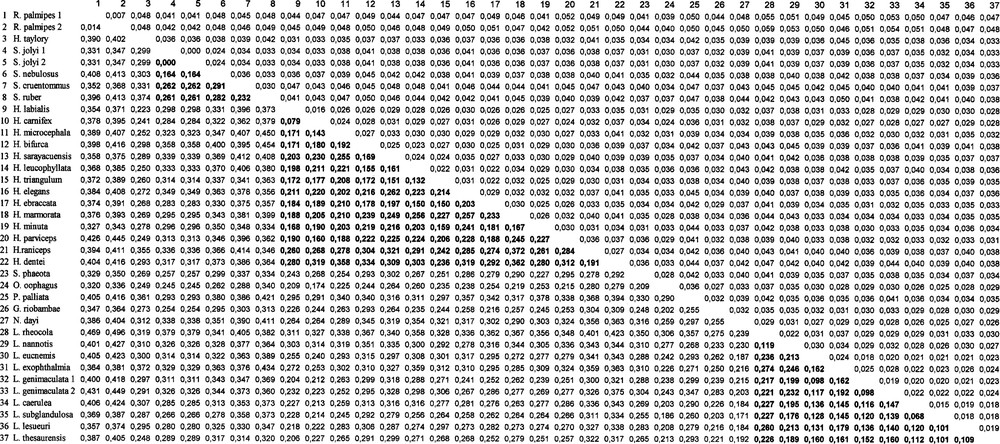

Pairwise comparisons of nucleotide divergences (below the diagonal) and standard errors estimated according to the method of the two-parameter distance of Kimura (above the diagonal) for the different species, using the 332 positions available for all the sequences. In bold: comparisons between species belonging to the same genus

3.1.2 Saturation

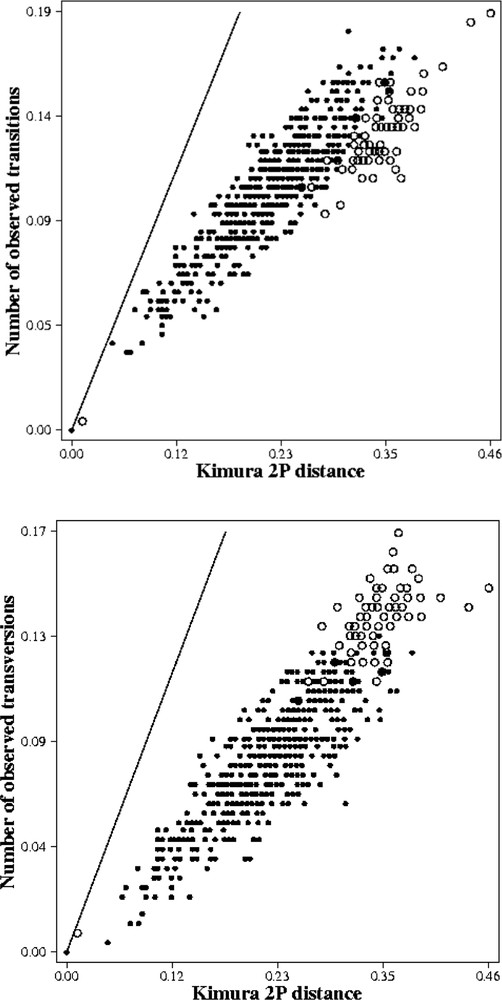

No saturation effects were observed for the transversion substitution patterns (Fig. 5b). For the transition substitution patterns, the distribution of the pairwise comparison between the out-group and the in-group suggested the beginning of saturation (open circle) (Fig. 5a). This is why we used a weighted parsimony of 2:1 (2 for the transversions and 1 for the transitions), and the Kimura two parameters distance for the NJ.

Saturation plots obtained from 332 positions of the 16S rDNA of 37 species. X axis: pairwise number of substitutions when using the Kimura 2 parameters model; Y axis: pairwise number of substitutions when using the transitions only (a). X axis: pairwise number of substitutions when using the Kimura 2 parameters model; Y axis: pairwise number of substitutions when using the transversions only (b).

3.1.3 The ILD test

The test for incongruence between the variable domain and the conserved domain yielded a P value of 0.56, showing that there is no more character incongruence between these two zones than one would expect by chance alone. Thus, one should simultaneously treat the two partitions.

3.2 Hylinae

The monophyly of Hylinae was tested using 427 bp of the 16S rDNA sequence. Due to the impact of short sequences on the tree topology, we excluded the Smilisca phaeota sequence (representing another genus of the Hylinae), but we retained the Litoria and Nyctimystes sequences (representing the Pelodryadinae). Of the 427 positions, 201 were informative (gaps were treated as missing) for the weighted 2:1 parsimony. We found three equally parsimonious trees (1503 steps). The g1 value was –0.612, suggesting the 16S rDNA data set contains a phylogenetic signal. The CI (consistency index) was equal to 0.375 suggesting a high level of homoplasy but the RI (retention index, less sensitive to some artefact) was equal to 0.567 (indicating that the CI overestimated the content of homoplasy).

The two tree-making methods (MP and NJ) produced similar topologies, and the Templeton test showed that the two trees were statistically indistinguishable.

Rooting on the Rana palmipes species, the two topologies displayed a basal dichotomy of the Scinax genus, which constituted a monophyletic group, and a cluster constituted of the Litoria, Nyctimystes, Hyla, and Osteocephalus genera (Fig. 6). The statistical support for this branching pattern was high (BP = 96/81 and BP = 84/77); the decay index (DI) was respectively equal to 7 and 10. The Hylinae was paraphyletic, given the position of the Litoria as the sister-group to the Hyla and the Osteocephalus genera. The Litoria genus was monophyletic if we consider the N. dayi species as a member of the Litoria (BP = 96/100, DI = 19). The Hyla genus was monophyletic but the bootstrap proportion was low (BP = 52/63, DI = 7).

Bootstrap analyses carried out with 1000 iterations using the 427 pb of the 16S rDNA among 33 ‘species' of Hyla, Osteocephalus, Litoria and Scinax genera, with Rana palmipes as an outgroup, using Maximum Parsimony (bootstrap value on the top left), Neighbour-Joining on a matrix of the Kimura two-parameter model (right bootstrap value). Templeton's test indicates that the two trees are not significantly different in topology; therefore only the Neighbour-Joining tree is shown.

3.3 Hylidae

The monophyly of the Hylidae family was tested using the partial length (332 bp of the 16S rDNA sequence). Due to the required computer running time, we retained only four Litoria species and four Hyla species. Of the 332 positions, 171 were informative (gaps were treated as missing) for the weighted 2:1 parsimony. We found three equally parsimonious trees (1082 steps) with a CI equal of 0.460 and a RI of 0.535, indicating a low level of homoplasy. The g1 value was –0.993, suggesting that the 16S rDNA data set contained significant phylogenetic signal.

The two tree-making methods (MP and NJ) produced similar topologies, and the Templeton’s test showed that the three trees were statistically indistinguishable.

Rooting on the Rana palmipes species, the two topologies displayed the same basal dichotomy of the Scinax genus, which constituted a monophyletic group (BP = 87/87, DI = 8), and a cluster made up of the other sequences (Fig. 7). Surprisingly, the Hyalinobatrachium taylori species (representing the Centrolenidae family) clustered with the other Hylidae species (BP = 62/54, DI = 8) indicating the paraphyly of the Hylidae. The Pelodryaninae was monophyletic (BP = 97/78, DI = 6). The Phyllomedusinae was the sister-group of the Pelodryaninae, which itself clustered with the Hemiphractinae (BP = 77/-, DI = 3).

Bootstrap analyses carried out with 1000 iterations using the 332 pb of the 16S rDNA among 21 ‘species' representing the Pelodryadinae, Hylinae, Phyllomedusinae, Hemipractinae and Centroleninae subfamilies, with Rana palmipes as an outgroup, using Maximum Parsimony (bootstrap value on the top left), Neighbour-Joining on a matrix of the Kimura two-parameter model (right bootstrap value). Templeton's test indicates that the two trees are not significantly different in topology; therefore only the Neighbour-Joining tree is shown.

4 Discussion

4.1 The Scinax genus

The Scinax genus is divided into seven groups, but only three of which are represented in French Guiana: rostratus (Scinax jolyi, Scinax nebulosus), ruber (Scinax ruber), and X-signatus (Scinax cruentommus) 〚6〛. The molecular monophyly of the Scinax genus was supported by high bootstrap proportion (BP = 96/81 for the Hylinae tree and BP = 87/87 for the Hylidae tree), suggesting that the Scinax genus was a clade. These molecular results were in agreement with the morphology based on a shared derived character (i.e. the lack of webbing or reduced between toes I and II in adults) 〚41〛.

The phylogenetic reconstruction indicated that the ruber group was the sister-group of the X-signatus group. The X-signatus was the sister-group to the rostratus (represented in our study by S. joly and S. nebulosus). Genetic variation within Scinax genus was high (0.234 ± 0.023 for the partial alignment or 0.171 ± 0.016 for the complete alignment 427 bases) in comparison to the other genera represented in the analysis. Comparison with other studies 〚42,43〛 would be difficult, due to the varied pattern of substitution along the 16S rDNA, which could induce an over- or underestimation of the genetic distances, as shown in this study. This pattern of substitution indicated a true diversity in the Scinax genus rather than simply an acceleration of the rate of substitution for the Scinax genus. Indeed, we detected no significant difference in the branch lengths between the Scinax genus and the other genera.

4.2 The hylinae paraphyly

When using the partial taxa data set over the 427 positions, the Scinax genus confirmed the paraphyly of the hylinae with respect to the Pelodryadinae. The Hyla genus was not the sister-group of the Scinax genus. Furthermore, the Hylinae paraphyly observed between Scinax genus and Hyla genus was not the only example. The position of O. oophagus confirmed that the Hylinae subfamily was clearly paraphyletic (Fig. 6). Considering the 332-position alignment based on specimen representing the four subfamilies, the Hylinae is polyphyletic (Fig. 7). This is not surprising in the light of the morphology: the non-differentiated mandibularis is shared with the Phyllomedusinae and Hemiphractinae. The horizontal pupil and single-tailed sperm (two filaments for the Scinax genus) are shared with several subfamilies 〚6〛. This is why Duellman 〚44〛 considered this subfamily as an unnatural group, containing all those genera that had not been split off into the others subfamilies.

So it seems obvious that the genetic diversity of the hylinae subfamily continues to be underestimated due to its paraphyletic origin or polyphyletic (if we consider Fig. 7) of the species constituting this group. Indeed, to constitute a monophyletic group (a clade of hylinae), we must include the species belonging to the three other subfamilies (Pelodriadinae, Phyllomedusinae, Hemiphractinae) and the species belonging to the Centrolenidae family, Fig. 7). It will be important to analyse some new morphological characters and to conduct a cladistic analysis in order to redefine different subfamilies.

4.3 The hylidae paraphyly

The name Hylidae is defined as node-based name for the most recent ancestor of the Pelodryadinae (Australopapuan region), Phyllomedusinae (tropical Central and South America), Hemiphractinae (Panama and South America), and Hylinae (North, Central, and South America, Eurasia and Africa) and all of its descendants 〚10〛.

Our molecular results yielded the paraphyly of the Hylidae with respect to the Centrolenidae (H. taylori). The genetic variation between the H. taylori species and the other Hylidae subfamilies (excluding the Scinax genus) was equal to 0.291 ± 0.037. This variability was equal to 0.295 ± 0.036 when the Scinax genus was included (Scinax genus versus the other Hylidae members was equal to 0.332 ± 0.0376), indicating a closer relationship between the Centrolenidae and the Hylidae (without the Scinax) than between the Scinax and the other Hylidae. Our study agrees with the work of Ruvinsky and Maxon 〚16〛, who found a trichotomy made up of the Centrolenidae, the Hemiphractinae–Bufonidae group, and the Hylinae. The Centrolenidae, present only in America 〚6〛, seems to be a subgroup of the Hylidae, regardless of the species chosen for the analysis (in our case, H. taylori). These different results were not incompatible with the morphological characters. Indeed, Ford 〚10〛 raised the concern that the two synapomorphies (claw-shaped terminal phalanges and the presence of intercalary elements) that characterise the Hylidae family have respectively been found in some hyperoliids species for the first one, and in Centrolenids and Pseudids for the second one.

5 Conclusion

Partial sequences have been widely used in the assessment of relationships within and between lissamphibian genera 〚45〛. The sequencing and subsequent analysis of eleven new French Guiana frogs 16S rDNA sequences has allowed us to clarify several relationships among the hylids subfamilies. The Hylinae and Hylidae systematic units were not supported given that they do not correspond to a clade. However, it will be interesting to sequence some other genes (mitochondrial and/or nuclear) in order to resolve some phylogenetic relationships for which no resolution was found in using only partial 16S rDNA sequences.

These results have important implications: it would be interesting, in a phylogenetic tree, to consider the taxonomic units which were supported by the molecular data (bootstrap proportion ≥ 75%), in agreement with the rare morphological synapomorphies. These observations would be useful to define the taxonomic rank (with respect to molecular divergence). This work will be continued on two levels: (1) taking into account the variability which could be found at the genus level (e.g. for the Scinax genus) in using the complete distribution area of the species and (2) testing the monophyly or the paraphyly of each one of the ‘Hylidae’ subfamilies with the addition of the most complete genus data set. Our work could be used as a basis for a phylogenetic study of the batrachians that have yet to be studied in the French Guiana. Furthermore, some scientists suggest that phylogenetic diversity is the basis criterion of maximum genetic diversity. In this case additional information concerning the evolutionary history of the taxa is required 〚46〛. This information could be extract from the phylogenetic tree as proposed by Bossuyt and Milinkovitch 〚47〛.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jeffrey Rasmussen and Anne Miquelis for useful comments on the manuscript.

Version abrégée

La conservation des habitats riches en espèces du bassin d’Amazonie d’Amérique du Sud continuera à être un des défis du début de ce siècle. Un récent travail a établi un inventaire des espèces d’amphibiens de Guyane et d’Amazonie. Les auteurs de cet ouvrage y ont répertorié plus de 15 familles et 110 espèces, parmi lesquelles sept sont endémiques à cette région.

Avec plus de 40 genres et 680 espèces, les Hylidae constituent l’une des familles d’amphibiens les plus diversifiées. Elle est actuellement divisée en quatre sous-familles : Pelodryadinae, Phyllomedusinae, Hemiphractinae, et Hylinae. Les représentants de la famille des Hylidae ont en outre une très vaste aire de répartition : Amérique (Nord et Sud), Europe, Asie (à l’exception de l’Inde), Australie et Nouvelle-Guinée.

Les Hylinae constituent un groupe de lissamphibiens ne possédant pas les caractères discriminants des autres sous-familles. De plus les liens phylogénétiques de ce groupe demeurent obscurs, malgré les nombreuses études portant sur la morphologie, le comportement ou l’écologie. L’utilisation du gène mitochondrial 16S a permis de répondre à de nombreuses questions concernant la phylogénie des batraciens. Ainsi, notre travail porte non seulement sur l’étude des relations phylogénétiques du genre énigmatique Scinax (appartenant aux Hylinae), mais aussi sur les sous-familles des Hylidae, en utilisant ce marqueur moléculaire.

L’alignement des séquences des différentes espèces de Hylinae est réalisé en utilisant le programme Clustal X, puis analysé à l’aide de la structure secondaire de l’ARN ribosomique 16S. Cette procédure permet de localiser trois portions conservées (C1 = positions 1 à 204 et C2 = 284 à 325 et C3 = 346 à 427) et deux régions variables (V1 = positions 205 à 283 et V2 = positions 326 à 345). Deux méthodes d’analyse sont utilisées pour étudier les relations phylogénétiques : le neighbour-joining (NJ) et le maximum de parcimonie (MP). La topologie des arbres et la robustesse des nœuds sont testées à l’aide de différentes méthodes.

L’utilisation du test du χ2 montre que la composition en bases de chaque domaine n’est pas significativement différente. La variabilité génétique du genre Scinax est de 0,249 ± 0,025, alors que cette valeur est de 0,161 ± 0,016 pour le genre Litoria et de 0,224 ± 0.019 pour le genre Hyla. La variabilité génétique à l’intérieur de la famille des Hylidae est de 0,268 (± 0,04) en excluant le genre Scinax, et de 0,290 (± 0,04) en incluant ce même genre. Le niveau de différenciation entre les familles Centrolenidae et Hylidae est seulement de 0,295 (± 0,036). Ce résultat est à comparer avec celui obtenu entre les espèces du genre Scinax et les autres membres des Hylidae (0,332 ± 0,036).

La monophylie des Hylinae est testée en utilisant un fragment de 427 bp du 16S ADNr. La séquence de l’espèce Smilisca phaeota (représentant un autre genre des Hylinae) est exclue, car trop courte. En revanche, nous gardons les séquences des genres Litoria et Nyctimystes (représentant les Pelodryadinae). Sur les 427 positions, 201 sont informatives (les délétions ne sont pas prises en compte dans l’analyse) en utilisant une parcimonie pondérée de 2 pour les transversions et de 1 pour les transitions. Nous obtenons ainsi trois arbres équiparcimonieux (de 1503 pas). La valeur du g1 (–0,612) suggère que le jeu de données contient un signal phylogénétique significatif, avec des valeurs de IC (indice de cohérence) et de IR (indice de rétention) respectivement de 0,375 et 0,567, indiquant la présence d’homoplasie. Les deux méthodes de reconstruction utilisées (MP et NJ) donnent des topologies semblables, tandis que le test de Templeton montre que les deux arbres ne sont pas significativement différents. Nos résultats montrent que la sous-famille des Hylinae est paraphylétique au vu de la position du genre Litoria comme groupe frère des genres Hyla et Osteocephalus. Les genres Litoria et Hyla sont monophylétiques ; la position externe du genre Scinax confirme la paraphylie des Hylinae.

La monophylie des Hylidae est testée en utilisant un segment de 332 bp du gène 16S ADNr. Sur ces 332 positions, 171 sont informatives (les délétions ne sont pas prises en compte dans l’analyse) en utilisant une parcimonie pondérée de type 2:1. Nous obtenons ainsi trois arbres équiparcimonieux (de 1082 pas) avec des valeurs de IC et de IR respectivement de 0,460 et 0,535, indiquant un léger taux d’homoplasie. La valeur du g1 (–0,993) suggère que le jeu de données contient un signal phylogénétique important. Les deux méthodes de reconstruction utilisées (MP et NJ) donnent des topologies semblables ; le test de Templeton montre que les deux arbres ne sont pas significativement différents. En enracinant sur l’espèce Rana palmipes, les deux topologies montrent la même dichotomie basale, qui est formée, d’une part, par les individus du genre Scinax (constituant un groupe monophylétique, BP = 87/87) et, d’autre part, par l’ensemble des autres séquences. De plus, l’espèce Hyalinobatrachium taylori (représentant la famille des Centrolenidae) se regroupe avec les autres espèces d’Hylidae (BP = 62/54), ce qui induit la paraphylie des Hylidae et la polyphylie de Hylinae. Les Pelodryaninae sont monophylétiques (BP = 97/78). Les Phyllomedusinae constituent le groupe frère des Pelodryaninae, lui-même regroupé avec les Hemiphractinae (BP = 77/-).

Le séquencage et l’analyse d’une partie du gène 16S ADNr de onze nouveaux spécimens de grenouilles de Guyane française nous permettent de clarifier les relations phylogénétiques au sein des quatre sous-familles de Hylidae. Les unités systématiques que sont les Hylinae et les Hylidae ne sont pas soutenues ; de ce fait, ces deux niveaux taxonomiques ne correspondent pas à des clades.

Ces résultats ont des implications importantes : ils suggèrent la nécessité de redéfinir les Hylinae et les Hylidae. À cet effet, il serait intéressant dans un arbre phylogénétique de considérer les unités taxonomiques qui sont soutenues par les données moléculaires (proportion de bootstrap significative ≥ 75%) en accord avec les rares synapomorphies morphologiques. Cette observation nous permettrait de redéfinir leur rang taxinomique en tenant compte de la divergence moléculaire.

Ce travail peut être poursuivi et approfondi à deux niveaux (1) par l’analyse de la variabilité au sein des espèces du genre Scinax en utilisant l’aire de répartition géographique du genre et (2) en testant la monophylie ou la paraphylie de chaque sous-famille de « Hylidae » en incluant un plus grand nombre de spécimens dans l’analyse. Notre travail peut être utilisé comme base pour une étude phylogénétique plus vaste des batraciens de la Guyane française, encore mal connus, et être utilisé en vue d’une meilleur estimation de la biodiversité de ce territoire.