1 Introduction

Saltmarshes constitute dynamic environments that present characteristics of both marine and terrestrial systems. The physical feature of tides, sediments, freshwater inputs and shoreline structure determine the development, extent and structure of saltmarshes within their geographical range [1]. Because of the existence of stressful saline conditions that limit plants colonization, saltmarshes are generally perceived as ecosystems with low plant diversity. Indeed, along a sea-land elevation gradient, five to ten halophytic species are commonly colonizing European saltmarshes (e.g., [2]).

Saltmarshes vegetation exhibits distinct zonation patterns, determined by a combination of salinity, waterlogging stress, and interspecific competition [2,3]. Natural and anthropogenic disturbances also play a key role in the organization and maintenance of plant communities (e.g., [2,4–6]). In European saltmarshes, anthropogenic activities are particularly important as most saltmarshes are exploited agriculturally [7]. Haymaking has gradually decreased, and nowadays the most widespread use of saltmarshes is livestock grazing. Seventy per cent of the northwestern European saltmarshes are still exploited, even if the area of abandoned saltmarshes is rapidly increasing [8]. Such utilization of saltmarshes sometimes favors plant richness and diversity and controls the spread of competitive species that could otherwise expand in dense monospecific stands [8–11]. Nevertheless, heavy grazing causes the development of short monospecific plant communities [12,13]. In Germany, cessation of grazing was recommended for the lower and middle marshes to maintain diversity [14]. In non-grazed salt marsh, the dynamic and heterogeneous geomorphological structure was considered to be enough to enhance plant diversity and prevent the dominance of a single species. Long-term studies on the effect of grazing on plant diversity in salt marshes remain scarce, despite the fact that they are essential to understand the consequences of change in human activities (i.e., cessation or intensification of grazing) and to create decision tools for management scenarios [8].

The goal of this study was to provide an overview of the saltmarshes plant communities in Western France and their change over time due to the presence or absence of grazing activity at various intensity levels (i.e., moderate to over grazing) in order to pursue the debate of potential management and/or restoration decisions. To achieve this goal, we investigated the following two objectives: (1) description of the changes in plant communities over a ten-year period and at a large scale (i.e., 4000 ha), in relation to the presence, absence and frequency of grazing; and (2) evaluation of the change in plant communities after abandonment of sheep grazing in experimental plots. For each of these objectives, plant communities were described with species composition, species richness, and species diversity. Potential management options and their constraints are evaluated in the discussion section.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study site

The study was carried out in the Mont Saint-Michel (MSM) Bay located in western France (48°40′N, 1°35′W). Most of the 4000 ha of saltmarshes are utilized for sheep production, while other areas of saltmarshes have been maintained closed to grazing (Fig. 1). Sheep graze the saltmarshes all year around, but are less numerous during winter. We call “natural” saltmarshes the areas that are not grazed and “grazed” saltmarshes the areas where grazing is occurring.

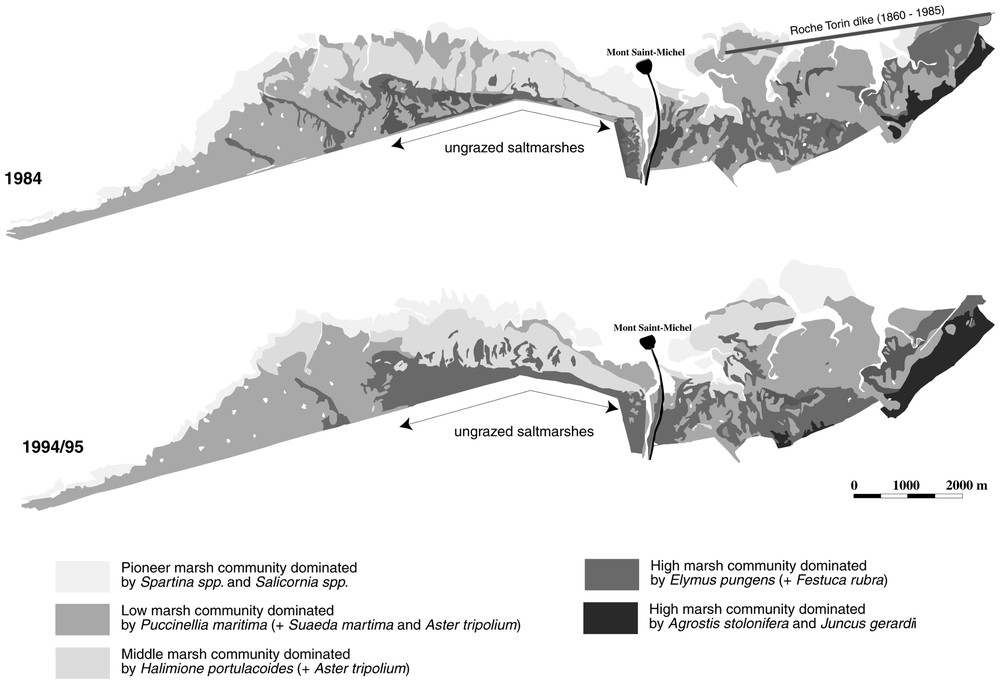

Vegetation maps established in 1984 and in 1994/95 of the saltmarshes located on both sides of the MSM. Most of the saltmarshes are grazed, with the exception of the ones located right west to the MSM.

Based on plant communities, natural saltmarshes can be divided into four zones: (1) a pioneer marsh colonized by Spartina spp. and Salicornia spp.; (2) a low marsh dominated by Puccinellia maritima, Aster tripolium and Suaeda maritima; (3) a middle marsh dominated by Halimione portulacoides and Aster tripolium; and (4) a high marsh with Elymus pungens and Festuca rubra. These zones are linked to flooding frequency [15,16]. Under grazing conditions, this plant zonation tends to disappear and Puccinellia maritima is generally present along the entire sea-land elevation gradient. In areas influenced by freshwater input, community of Agrotis stolonifera colonizes the grazed high marsh (Fig. 1).

2.2 Large scale mapping of saltmarshes vegetation

Vegetation maps of the saltmarshes were established successively in 1994 [16] and in 1994/95 [17] to draw an overall picture of the evolution of plant communities on a large scale and over a ten-year period. Aerial photographs were used to delineate the extent of saltmarshes and to identify patches representing the main communities. Field verifications were made in the summers 1984, and then 1994–95 to identify these communities. Detailed observations were also conducted along five land-sea transects in areas influenced by various degrees of grazing disturbances (i.e., no, moderate or over grazing). For each distinct plant community, species richness and number of individual was estimated using the cover scale of Braun-Blanquet [18]. Vegetation communities were then described according to the dominant species as describe in the legend of Fig. 1. Thus the categories of pioneer, low, middle and high marshes were based on plant communities, and not on elevation.

2.3 Floristic analysis at the MSM Bay level

For each releves made in 1994–95, we calculated the diversity (H′) using the Shannon index [19], species richness (S) and evenness (J′) [20]. Because our field sampling used the categorical method of Braun-Blanquet cover-scale, we first converted this scale into a continuous cover record using the median value of cover for each class. Vegetation releves were classed according to grazing intensity in three distinct classes: no grazing (i.e., natural), grazing, and overgrazing. These classes were based on the number of sheep that occupied the area [16]. We used one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) to determine whether the three indexes of diversity differed significantly between the three classes of grazing activity. Tests for normality were performed on the data sets, but no transformations were required to meet parametric assumptions for ANOVA.

2.4 Experimental exclosures

In January 1994, three 15×15 m exclosures were established in a heavily grazed area dominated by Puccinellia maritima. The first exclosure was established at proximity to the sea wall, in an area less frequently flooded and with poor drainage network. The second exclosure was located at equal distance between the dike and the mud flat, in a well-drained area. The last exclosure was established close to the mud flat. Despite the absence of the “typical vegetation” due to the presence of grazing, these three exclosures were considered as belonging to the high, middle and low marshes, respectively.

Plant cover was recorded once a year from 1994 to 2001 using the point contact method in ungrazed conditions (i.e., inside the exclosures) and in grazed conditions (i.e., outside the exclosures). Species were recorded every 10 cm along three 10 m permanent lines which were located 4 meters apart (3×100 points per treatment) in September. The cover was calculated each year for each species (number of species contact on the line/100). The Shannon index, species richness and evenness (see above) were calculated each year for each line.

3 Results

3.1 Changes of saltmarsh structure in ten years

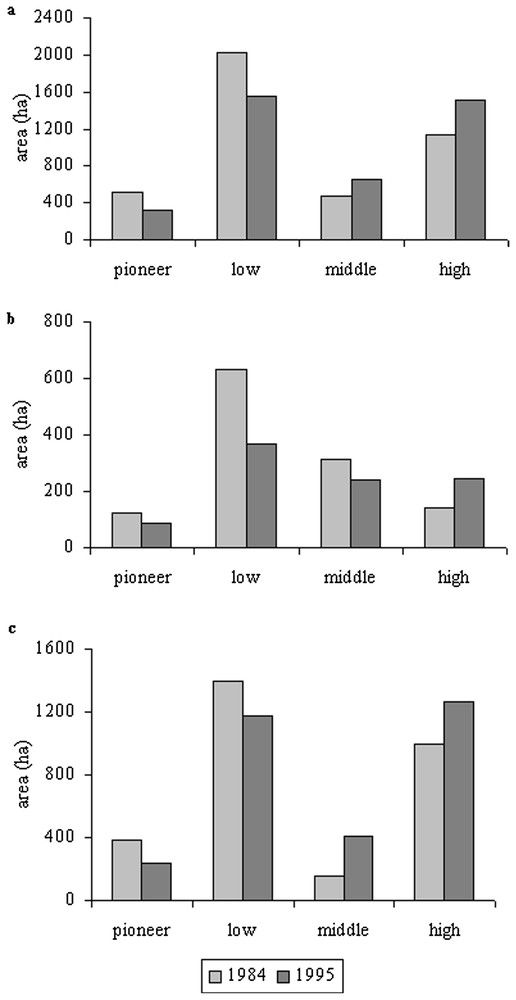

The overall area of saltmarshes remained stable between 1984 and 1995 (∼4140 ha and 4040 ha, respectively), but we observed a small increase of grazed saltmarshes over the natural area. In 1984, 71% of the saltmarshes were grazed, while 77% were grazed in 1995. At the bay level, we observed a 40% increase in middle marshes area and a 33% increase in high saltmarshes area between 1984 and 1995, while the area of pioneer and low marshes decreased by 36% and 24%, respectively (Fig. 2a). In natural conditions, there was a net decrease of each sector of saltmarshes, with the exception of the high marsh, which extended by 76% in ten years, certainly to the detriment of the middle marsh, which decreased by 22% in area (Figs. 1 and 2b). Finally, under grazed conditions (Figs. 1 and 2c), we observed a similar pattern that was already noted at the bay level, with an increase of both middle and high marshes (162 and 27%, respectively) and a decrease in the area of both pioneer and low marshes (38 and 15%, respectively).

Extent of pioneer, low, middle and high marshes in 1984 and 1994: (a) at the bay level, (b) in natural areas, (c) in grazed areas.

3.2 Impact of grazing on species composition

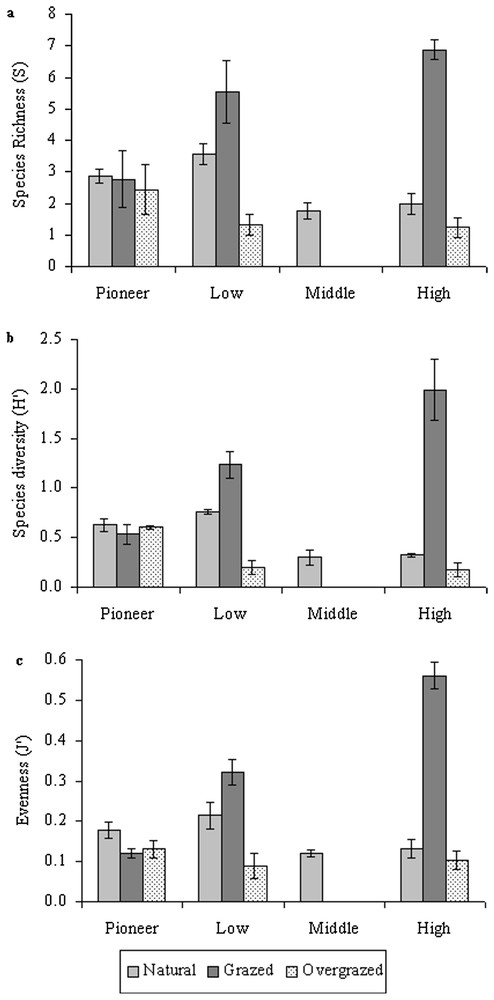

In the pioneer zone, there were no differences in species diversity, species richness and evenness between the natural, grazed and overgrazed marshes (Fig. 3). For the low, middle and high marshes, richness, diversity, and evenness were significantly lower (p<0.001) in the natural marsh than in the grazed marsh (Fig. 3), but these three indexes were significantly higher in the natural marsh than in the overgrazed marsh (p<0.001). Because of our classification of marsh zones based on plant communities, the middle marsh dominated by Halimione portulacoides occurred only in absence of grazing. Finally in the high marsh, significantly higher diversity, richness and evenness were observed in the grazed marsh compared to the natural and overgrazed marshes (Fig. 3).

Estimation of (a) species richness, (b) species diversity and (c) evenness along the elevation gradient in natural, grazed and overgrazed conditions. Errors bars represent ±1 SE.

In natural marshes, the higher diversity and richness was significantly higher in the low marsh compared to the middle and high marsh where competitive species (i.e., Halimione portulacoides and even more Elymus pungens) usually occupied large monospecific areas (Fig. 3). In the presence of grazing, the high marshes were significantly the most diverse and rich zone with the colonization of numerous species (i.e., Agrostis stolonifera, Juncus gerardii, Festuca rubra, Lolium perenne). The most diverse communities of high marsh were found in the presence of freshwater input (Fig. 1). In overgrazed salt marshes, the most diverse plant communities where found in the low and pioneer marshes (Fig. 3).

3.3 Experimental cessation of grazing

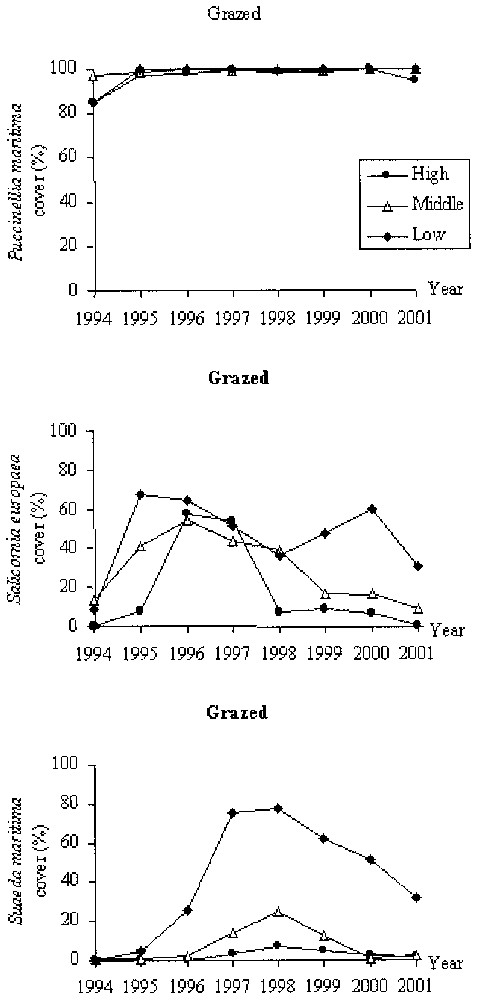

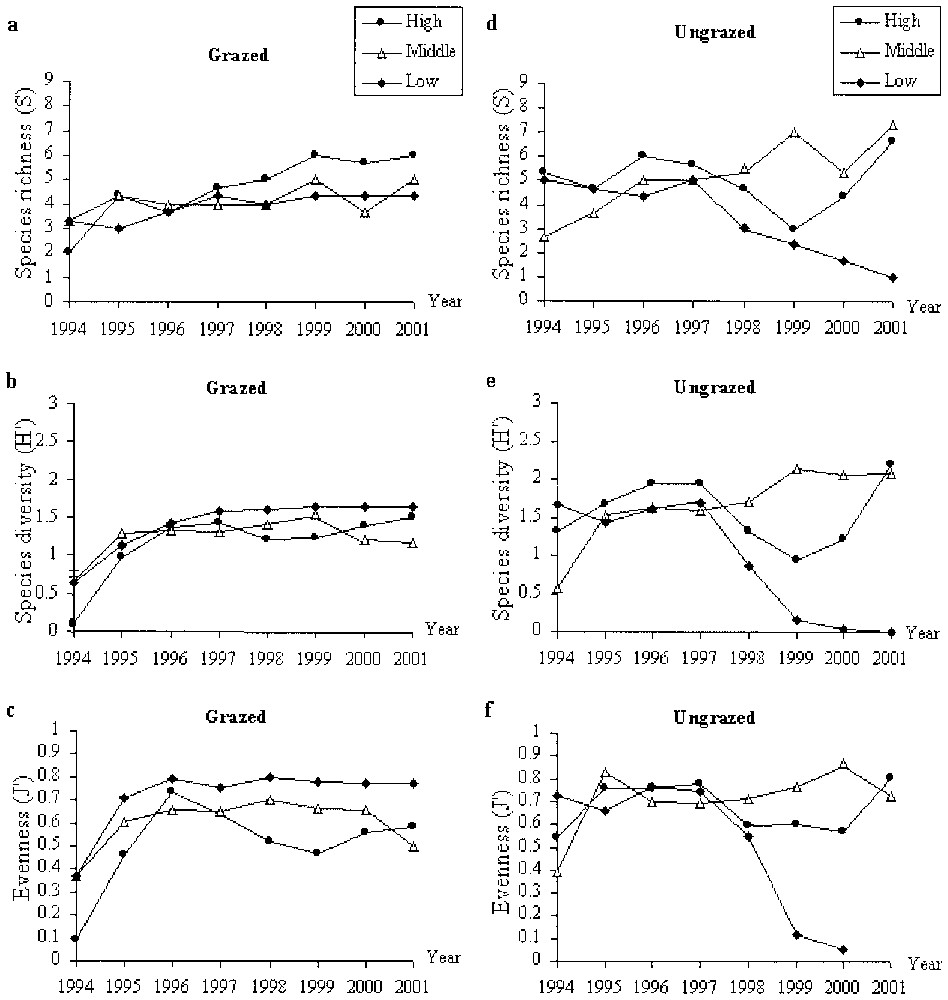

In grazed conditions, the vegetation was strongly dominated by Puccinellia maritima (Fig. 4). In 1994, the cover of bare soil was high (between 3 and 15%) while the cover of annuals species (e.g., Salicornia europaea and Suaeda maritima) quite low and the cover Puccinellia maritima was at its minimum. After 1994, bare soil was absent and the cover of the two annuals increased. The cover of Salicornia europaea and Suaeda maritima decreased after 1996 and 1998, respectively. In the high marsh, the species richness increased continuously (except in 1996) from 1994 until 2001 (Fig. 6a). In the three locations (i.e., high, middle, low marshes), species diversity and evenness increased until 1996 and then remained high until 2001 (Fig. 6b and c). In the low marsh these indexes decreased slightly between 1996 and 1999 and then increased, while in the middle marsh these values decreased lightly from 1999.

Change in cover of three dominant species, Puccinellia maritima, Salicornia europaea and Suaeda maritima in grazed conditions in the high, middle and low elevations of the saltmarsh.

Change of species richness, species diversity and evenness in grazed and ungrazed conditions between 1994 and 2001 in the high, middle and low elevations of the saltmarsh.

After cessation of sheep grazing, Puccinellia maritima cover decreased slowly in the high and middle exclosures and dramatically in the low exclosure after 1997 (Fig. 5). In this exclosure, Halimione portulacoides cover increased quickly between 1995 and 1998. Elymus pungens established in 1998 in the middle marsh and reached 36% cover in 2001. The decrease of Puccinellia maritima was concomitant with the establishment and the expansion of Elymus pungens and Halimione portulacoides. In the high exclosure, species richness, species diversity and evenness remained high but with great fluctuations and with a maximum in 2001 (Fig. 6d, e, f). In the middle exclosure, these values increased between 1994 and 2001 with light fluctuations. In the low exclosure, Species richness, Species diversity and Evenness stayed high till 1997 but then drop dramatically till 2001 (Fig. 6d, e, f). This trend was the same as the trend observed with Puccinellia maritima cover.

Change in cover of three dominant perennials, Puccinellia maritima, Elymus pungens and Halimione portulacoides in the high, middle and low exclosures.

4 Discussion

Saltmarshes have been exploited for centuries along the coasts of Europe. In some areas of the Wadden Sea, these ecosystems have been so heavily “engineered” (i.e., modification of the flow pattern) to facilitate human development [7] that restoration of channel creeks is now occurring. In the MSM Bay, traditional grazing and hay harvesting have also modeled the saltmarshes during decades [16] but not so heavily as in the Wadden Sea. Recently, modification of agricultural practices has resulted in secondary changes in the plant community diversity and spatial arrangement. Hay harvesting used to maintain Festuca rubra in the high marsh, and the abandonment of this activity has recently promoted the spread of a monospecific stand of Elymus pungens [17]. Cessation of cattle grazing has severely reduced the population of the endangered species Halimione pedunculata in the bay and others sites along the French coast.

Sheep grazing, however, is still economically attractive, but is only sustainable for farmers if they increase the size of their herds [16,21]. If some farmers have intensified their sheep production, others have abandoned this activity. As a consequence of local intensifications of sheep grazing, we observed a noticeable increase of the total area of grazed salt marshes (71% to 77% in ten years) and of local overgrazing that create area with bare mud and low diversity. In these saltmarshes where grazing has been abandoned in the last ten years, the middle marsh is locally increasing (Fig. 1) [17]. The most dramatic trend in natural marshes is the 76% increase of high marsh community (which is predominantly occupied by Elymus pungens) and a low species richness and diversity. Elymus pungens is spreading all over European salt marshes [22]; it is a strong competitor for nitrogen, tolerant to environmental conditions, and capable of clonal expansion [11]. Overgrazing similarly leads to a severe decrease in species richness and diversity in most of the sectors of the marsh (with the exception of the pioneer marsh). Even if it does favor the low marsh community at Puccinellia maritima, moderate grazing contribute to enhance plant richness and diversity. In the area where we set up our experimental exclosures, the herd was diminished by approximately 500 sheep between 1994 and 1995; thus this marsh went from an overgrazed to a moderately grazed system, and we indeed observed an increase in annual species and in the overall plant diversity and richness after 1994. Extensive sheep grazing has also been generally recommended by studies made along the Wadden Sea; it produces a mosaic of patches with heavily and lightly grazed areas and promotes plant and habitat diversity [12,23].

Abandonment of sheep grazing resulted in changes in vegetation pattern as demonstrated by our experimental exclosure and other previous studies [8–10]. In the lower exclosure, the expansion of the clonal species Halimione portulacoides was fast. In 2000 and 2001, this exclosure was entirely occupied with a monospecific stand of Halimione portulacoides with a null diversity. In the upper and lower exclosures, Halimione portulacoides and Elymus pungens were respectively scarce or absent before exclosure establishment and were still not widespread 8 years after cessation of grazing. The establishment of Elymus pungens certainly resulted from seeds input from populations located 500 m away. Nevertheless, the clonal expansion of this species is expected in the future with a drop of species diversity like it occurred in the old abandoned saltmarshes of the MSM Bay.

Plant diversity has a profound influence on the functions that the plant community performs as part of the physical structure and energy transfer component in an ecosystem (i.e., [24,25]). Maintenance of plant richness and diversity in saltmarshes with livestock grazing enhance the value of these ecosystems for waterfowl habitats [26]. However areas of salt marshes that support diverse plant communities (i.e., pioneer and low marshes communities) are generally less productive, thus decreasing the potential for outwelling of organic matter to coastal marsh [21,27]. While fish communities invade channel creeks of natural marshes during tidal flooding to feed on macroinvertebrates and benthic algae, sheep grazing negatively disrupts this food web [28]. In contrast, moderately grazed marshes support a more diverse macroinvertebrates community, which disappear after cessation of grazing [12]. In the debate that extends from the absence of human intervention and the management of ecosystems to reach a particular ecological goal, European saltmarshes provide an interesting case study where management decisions can lead to conflicting ecological results. To maintain plant diversity and heterogeneity of habitats for waterfowl, moderate grazing should be encouraged. In contrast, natural salt marshes support of more productive plant communities from which the coastal food web benefit.

In addition to agricultural practices, saltmarshes are also under the influence of other severe anthropogenic influences such as nitrogen enrichment [11,22]. As more of these anthropogenic encroachments will increase, the development of management strategies will become critical [29] to protect the diversity of ecological functions that saltmarshes provide (i.e., support of diversity, primary production, food web, habitat). The success of conservation of salt marshes will depend on how well human activities can be used as strategies restore and preserve this multitude of ecosystems functions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Kellie DiFrischia who helped with the English style of this manuscript. This research was supported by the European Union – Research Directorate XII (grants #EV4V-0172-FEDB, #EV5V/CT92/0098, and #316991MVB341), the DIREN-Bretagne, and the « Conservatoire du Littoral et des Systèmes Lacustres ».